Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stack - Value and Facts

Uploaded by

mehmetmsahinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stack - Value and Facts

Uploaded by

mehmetmsahinCopyright:

Available Formats

205

DISCUSSION

VALUE AND FACTS

GEORGE J. STACK

In his essay "Two Dogmas o.f Empiricism" W. O. Quine identified the

two unquestioned assumptions of empiricism as the belief in the radical

distinction between analytic and synthetic truths, and reductionism. There

is also a third dogma of empiricism which may not be universally shared by

all empiricists, but which is a fundamental assumption of empiricism in

general. That is the belief that factual statements are value-free or are entirely distinct from, or unrelated to, values of valuation. It will be my intention here to try to show that this dogma is a questionable one and one

which attributes to factual assertions or factual judgments a putative

epistemic neutrality which, in fact, they do not possess. Although it will be

urged that the distinction between facts and values is both useful and inevitable, this distinction is not as radical as some empiricists might maintain. Although it may generally be agreed today that values are, in a sense,

empirical facts, I think that few would agree that, in a sense - a non-trivial

sense - facts are value-laden.

Before discussing the way or ways in which values infiltrate factual claims,

a few questions concerning the nature of facts must be raised. It is paradoxical that, although everyone would say that there are facts, there is

considerable controversy concerning the nature o~ facts themselves. The

term "fact" is itself somewhat vague. On the one hand, there are those

philosophers who maintain that facts simply a r e and are not, unlike propositions, either true of false. On the other hand, there are those (for example,

C. J. Ducasse) who claim that facts are propositions of a certain kind. Traditionally, facts have been described as "objective data" or the phenomena

which factual statements refer to or "picture." Facts are identified with

what makes propositions true. Those who claimed that propositions

"picture" facts (like the early Wittgenstein) presuppose a correspondence

theory of truth which is itself undermined by the epistemological structure

which is built upon its assumption. That is, the statement, "Language pictures the world or the totality of facts," is neither a tautology nor an analytic

proposition nor an empirically significant proposition. Hence; the nature of

its claim to truth is undeterminable. Although so large a question is not our

concern here, it is clear that the question of the relationship between language and facts is relevant to the question of the nature of facts. Moritz

Schlick once expressed this difficulty in the following way:

206

The Journal of Value Inquiry

the judgment is something completely different from that which is judged ... it

is not like that which is judged... Fox the concepts occurring in the judgments are

certainly not of the same nature as the real objects which they designate, and the

relations among concepts are not like the relation of things.1

This distinction between the factual judgment and the facts about which

the judgment is made (if it is a tenable one) provides a lacuna into which

a logical wedge could be driven. This logical wedge can be, I believe, bridged

by an act of interpretation. For the moment, however, our concern is with

the ambiguity of the term "fact."

In one sense, it is clear that a perceived datum (whether it is described

as a sense-datum or an object or, for that matter, a "combination of objects")

is not, strictly speaking, a fact. In order to be aware that my watch is on a

table, I must perceive a set of phenomena or I must perceive the presence of

objects in specific spatial relationships. The fact, some might say, is "discovered" in the perceptual act. But, is this truly the case,? Let us assume the

following hypothe~tical case. An individual called upon to describe what he is

perceiving is capable of using forms of the verb "to be" and is able to, express

spatial relations. Unfortunately, he is unable properly to use the words

"table," "my," or "watch." Now, such an individual would be able to

describe what he has perceived in the following way: "That is on that."

Clearly, he cannot convey a meaningful bit of factual information in this way

(even though he may be able to draw a sketch of what he has seen and

thereby transmit some information). What this case illustrates is that when

we perceive common objects we rapidly "interp,ret" the data we are perceiving. This interpretative process becomes, in time, so, habitual that we do

not realize that we are engaged in it. Such a process is revealed, however,

when we perceive objects or phenomena under peculiar circumstances or

when objects which resemble many other objects are perceived. In tactile

sensory experience this interpretation of the immediate datum perceived

is even more apparent. For, the immediate touch sensation is not, say, "hot,"

"cold," or "warm." To say, for example, "This object is warm," requires

a judgment about what is immediately experienced, an interpretation of the

primitive tactile datum which is a particular kind of touch sensation. The

difficulty which individuals possessing normal vMon have (when blindfolded) in accurately identifying the shape of objects: suggests, at least, that

(as Berkeley pointed out) perception involves the synthesis of the data

acquired through the various modalities of sense, a process which can be

described as fundamentally interpretive. In order for the objective datum to

be described as a fact, it must be "made" intelligible. But an event or occurrence (say, a flash of lightning) is: not in itself intelligiNe; its intelligibility

seems to lie in the logical form of the description of it. It makes sense to say

that "There is a flash of lightning" is true or false; but what sense does it

make to say that a flash of lightning is itself true or false? The problem of

determining what facts are is not merely a problem of terminology. For, if

1 Moritz Schlick, Allgemeine Erkenntnislehre, Berlin, 1925, p. 56.

Discussion,

207

we assume that only certain kinds of propositions are facts, then how are

we to describe the data which these facts "picture," "refer to,," or describe?

What is there or present to perception continues to be there whether we call

them facts or not. Now, one of the consequences of calling facts a type of

proposition (e.g., a contingent statement) is the implication that all contingent propositions are true or appear to embody a truth-claim. Thus, for

example, if I say that p is a fact, the implication is that "p" is. true. For,

when we describe a statement as a fact we seem to, say, by implication, that

it is true or is a verified or confirmed fact. We are led to. talk of positive

fact-statements and negative fact-statements rather than saying that " p " is

true because it describes a state of affairs in the world o.r is false because it

does not describe a state of affairs: in the world. There seems to. be good

reason for maintaining the distinction between fact-statements and the: facts

they purport to "report" or describe. If we desire to, keep the notion that

facts are contingent statements or propositions, it may be possible to, talk

about the objective data by using the terms factum or facta. Thus, lacta

would be the data or phenomena or collection of objects which are referred

to in factual statements or by F-propositions (fact-claiming propositions as

distinct from the truth-claims of tautologies, or analytic statements). However we designate the data to which F-statements refer, the question of the

valuational element implicit in the selection and designation of facts remains.

Although it is often admitted that the social sciences are not or perhaps

cannot be completely value-free, it is. usually said that the biological o,r

physical sciences are truly value-free. The "pure" description of facts is, often

considered as one of the bases of scientific method or the scientific approach

to nature. Although one may admit that it is difficult to separate the, purely

factual and the evaluation contents of some of the terms: used in the social

sciences,2 this separation is not merely possible in, say, the physical sciences;

but is actual. If one is to. argue that "facts" are, as it were, value-laden, it is

necessary to show that this is the case in what is generally considered the

paradigm of science as such, the physical sciences. Before attempting to. do

this, some general remarks concerning the influence of value on the identification of facts can be made.

In the first place, it may be asked why anyone believes there are facts at

all (i.e., facta). In the second place, one may legitimately ask why facts: are

construed in the way they are construed. To speak of objective facts which

are discovered by man or which present themselves to. perception is to assume a cultural viewpoint in which facts (or factual knowledge) are prized

or valued. Historically, factual explanations followed in the: wake of mythical

or religious explanations. That is, impersonal, non-mythic accounts of

natural phenomena replaced the previous modes of explanation. In the

earliest Greek philosophers (e.g., Thales) one can see the curious (to our way

of thinking) intermixture of poetry, animism, and science. T o pnt it briefly,

the factual orientation of Western man has historical roots which have been

2 Ernest Nagel, The Structure of Science, New York, 1961,p. 491.

208

The Journal of Value Inquiry

and could be traced. What this means, in general, is that at various stages

of his development man had to "choose" which modes of description or

interpretation he would apply to the natural world. Although this "choice"

is strictly metaphorical, it is clear that some group or some individuals did

decide what explanations would count as factual and which would be dismissed as fictive, or mythical. This general orientation towards the way in

which the world is to be understood can, I believe, be described as a cultural

"set" or a cultural value, ff this generalization seems to claim too much, it

could be shown that there are historical instances in which men came upon

certain discoveries which remained undeveloped because of what I have

called the prevalent cultural value or set. This is the: case, for example, in

the ancient Greeks' discovery of the steamboat and their subsequent abandonment of its development. What a civilization, a people, a nation, a

culture values will often determine what they generally accept as, "true."

To choose, from the complex multiplicity of po,ssible phenomena, specific

phenomena, and to. identify such phenomena as "facts," reflects, in a general

sense, a particular value-orientation. The evaluation of facts or factual

explanation was not a necessary stage in the development of man or of human culture. That it has been an effective or a useful one is undeniable; the

point is that alternative ways of interpreting or understanding nature or the

world could have been (and occasionally have been) adopted by man. In this

general sense, then, one may say that facts or the factual orientation towards

nature or the world is a value or, more cautiously, an expression of a cultural

value. What Max Weber says about scientific truth in general may with equal

force be applied to a fact orientation. "The belief in the: value of scientific

truth is the product of certain cultures and is not a product of man's original

nature." 8 Although I think it is not necessary to, refer to, man's "original

nature" (whatever that may have been), Weber's point is. clear. There is no

obvious necessity in man's "choice" or "decision" to embrace "scientific

truth" as the ultimate paradigm of truth. And since the accumulation of

"objective" factual data is intimately related to the search for scientific

truth, the valuation o{ facts is also, culturally conditioned. If the above suggestions are valid, it is clear that, in a general way, facts. (or a dependence

upon factual data) are valuations insofar as "facts" are conceived of as

being "worth something" or as having value. This is not to say that facts (or

"facta") are values - that is, that the two terms are fused - , but that the

appreciation of the significance of facts is a value. Even if this rather general

statement of the intimate interrelationship, between facts and value is

dubious or questionable, there are more specific reasons for maintaining

that facts are valuational at least in some respects.

While the reliance on "hard data" or "brute facts" in empirical sciences

is usually unquestioned or unexamined, it has occasionally been noted that

values play a significant part in science, particularly as "determinants of

3 Max Weber, The Methodology o/the Social Sciences, Glencoe, Ill., 1949, p. 110.

Discussion

209

the meanings which are seen in the events with which it (science) deals." 4

This determination of the meaning of facts is basically a hermeneutic problem. A factual judgment is essentially an interpretive act. Isolated empirical

data are not significant in scientific understanding. The "objective" data

are inevitably related to, general evaluative concepts which "make them

worth knowing." What is significant about such data is ultimately derived

from generally accepted evaluative concepts. 5 In o~der to determine what a

fact is or in order to know how to, construe facts, we must assume some

evaluational criteria. If the language of factual judgment is that of physicalobject statements, this does not mean that the judgment is entirely value-free

or independent of cultural values universally adopted at a particular time.

"Physical objects are conceptually imported into the [knowing, judgmental]

situation as convenient intermediaries - not by definition in terms of experience, but simply as irreducible p o s i t s . . . " Such entities (i.e., physical

objects) are conceptually relevant as "cultural po,sits." 6 What W. O. Quine

has referred to as cultural posits are, I believe, reducible to cultural values.

What is to be noted here is that facts are construed in terms o~ conceptual

schema which are themselves evaluative. Thus, for example, if a philosopher

prefers to conceive of (and describe) physical phenomena in terms of

"processes," "interactions," "reciprocal interrelationships," or "events,"

this selected cognitive framework de~ermines how he conceives of facta.

But why is this framework accepted? Usually it is said that this "new"

framework is "better than" previous cognitive systems of explanations, or

is pragmatically valuable, or heuristically valuable, or is a more effective

conceptual schema. In science it is often said that explanation E' replaces

explanation E because "it is more consistent with the facts." It is to be

noticed, however, that there is a certain circularity involved here. For, it is

said that a set of facts (which are described in a newly adopted terminology)

are better explained by this more recent cognitive framework. It is assumed

that E' is more accurate because it more effectively deals with the phenomena in question. But this assumption itself is based upon a choice between E and E' which is surely not only made in terms of the data (or facta)

to be explained. Hence, it is safe to assume that an evaluation of the various

merits of E' over E is carried out. That is, there is some kind o~ value judgment made. It is clear that the objective data are not neutral data, but are

reinterpreted in the fight of an emergent value, a value which is very often

what Quine has called a cultural posit and which I would describe more

generally as a cultural value. T o understand physical phenomena "as" pro,,

cesses or "as" events already presupposes that a value-interpretation has

been made. Whereas Heidegger would say that a presupposed ontology

conditions our understanding of ontic of factual phenomena, I would want

4 Abraham Kaplart, The Conduct of Inquiry, San Francisco,, California, 1964, p.

382.

Max Weber, op. cir., p. 111.

6 W. O. Quirte, From a Logical Point of View, New York, 1963, p. 44.

210

The Journal o[ Value Inquiry

to maintain that culturally determined values (e,g., perhaps the sub-culture

of the scientific community) condition interpretation and hence our understanding of factual phenomena. In order to understand something as something, Heidegger has pointed out, "The 'as' makes up the structure of the

explicitness of something that is understood. It constitutes the interpretation." 7 Although Heidegger would deny that values, cultural or otherwise, lie at the basis of ontologies, he quite rightly points out that how we

interpret physical phenomena, empirical data, or nature itself will determine

our understanding of our relationship towards nature or to, the "world."

If the natural world is conceived of as a system of "things" which are to be

used or manipulated or exploited, then man's relation to these things is the

Nietzschean "mastering advance into world-conquest and world-rule." 8

The "thingification" (Verdinglichung) of nature was, Heidegger maintains,

a precondition for the emergence of a technological orientation towards

nature. Although Heidegger's conception of the detrimental effects of

"metaphysics" on the Western mind is an extravagant claim, his insights

concerning the radical reformulation of man's understanding of nature as

a whole or ontic phenomena in particular and its effects upon how one conceives of the "world" are profound. We do not have to accept the Heideggerian phenomenology of the "world" in order to agree with his general

view that man could have understood ontic phenomena or beings in ways

quite different from the way in which he has come to. understand such

phenomena.

Althotlgh it is granted that value judgments or valuations cannot be

entirely extracted, say, from historical accounts;9 it is thought that valuations do not enter into the protocol statements of the scientist. This, however, is not entirely the case. For, observation statements or protocol statements themselves involve "interpretations" of the facts observed." 10 But

surely interpretations are selected from a number of possible alternatives and

reveal a particular theoretical preference or valuation. Observed data are

not, in themselves, intelligible; in order to "make" them intelligible or to

transform them into an intelligible structure (e.g., facts or F-statements), they

must be interpreted; but no interpretation of any data is purely neutral or

entirely divorced from implicit or explicit valuations. If, for example, a

theory or hypothesis is embraced in terms of, say, "epistemie utility," this

is clearly an expression of value. When the Japanese physicist Yukawa

postulated the "existence" of neutral mesons or neutrettos he did so, in

terms of an assumption of the symmetrical structure of nuclear fields, an

aesthetic consideration which clearly reflects the influence of non-factual

valuation considerations on his theoretical preferences. 1~ In the convention7 Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, Ttibingen, 1963, p. 149.

s Martin Heidegger, Nietzsche, Pfullingen, 1961, II, p. 171.

9 Morto~ White, Foundations of Historical Knowledge, New York, 1965, p. 4ft.

10 Rudotf C~rrtap, Erkenntnis, 2 (1932), p. 107.

11 Lo,uisde Brog[ie, Physics and Microphysics, New York, 1960, p. 37.

Discussion

211

alism of Henri Poincar6 we can again see the significance of valuation

preferences upon the selection of viable hypotheses. When attempting to

discover which hypothesis best explains a given set of facts or phenomena,

we are faced with a problem of choice. This choice, Poincar6 suggested,

must be guided by considerations of simplicity.~e Clearly, the principle o~

simplicity is not justified in terms of an appeal to, factual data or any observed phenomena. The statement, "The best hypothesis is: the simplest

one," is not analytically true, not tautological, and not an empirical statement. It clearly has the form of a value judgment. It has recently been said

that the selection of the simpler of two, theories can be justified in terms of

"beauty" and "convenience." a~ Without concerning ourselves with the

question of the degree of probability of confirmation which a simpler theory

may possess, it is obvious that the above bases for preference of a simpler

theory or hypothesis are grounded in valuational preferences which are

similar to those which determine the interpretation of factual phenomena.

Strictly speaking, then, there are no uninterpreted factual data. Pure description is a myth. Factual phenomena are selected and this selective activity takes place in accordance with various criteria which are value-laden.

When a scientist appeals to the heuristic value of a theory or hypothesis o~

to its pragmatic value, he has revealed that his inquiry is not, strictly speaking, wertefrei. These values may be subjective, conditioned by generally

accepted beliefs of the scientific community at a particular historical mo,

ment, or may be expre:ssions of unanalyzed cultural values. It is clear that

"what we are prepared to recognize as fact depends to a large extent on the

values we hold." 24 And it is precisely such values which are the: unquestioned

assumptions of scientific inquiry and of the ordinary interpretation of facts.

What is accepted as "brute" facticity is often a veiled value-interpretation

of an ostensibly neutral factual phenomenon.

The description of nature or of factual phenomena is not possible without

the assumption of some theoretical structure. Even the most ordinary singular statements are invariably "interpretations of the "facts' in the light of

theories." 25 But it is clear that the theories which influence our interpretation of facts are, in the most general sense, historically conditioned.

The most significant historical phenomena, o~ course, are related to the

theoretical structures generally accepted by the scientific discipline in which

a specific theory is relevant. Often, changes in theoretical explanations bring

in their wake ontological reformations and changes in the most elemental

ix Henri Poincarr, Science and Hypothesis, New York, 1952,p. 146.

13 W. O. Quine, "On Simple Theories of a Complex World," in Probability, Confirmation, and Simplicity, ed. by M. H. Foster and M. L. Martin, New York, 1966.

14 Peter Caws, Science and the Theory of Value, New York, 1967, p. 63.

1~ Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery, New York, 1961, p. 423. Cf. Paul

Feyerabend, "Problems of Empiricism," in Beyond the Edge of Certainty, R. G.

Colodny, ed., New Jersey, 1965, p. 175: "... the description of every single fact [isl

dependent o,n some theory."

212

T h e Journal o f V a l u e Inquiry

meaning of the terms used.l~ It is for this reason that Heidegger's claim that

the scientist is engaged in the projection of nature is not wholly incompatible

with the views of some philosophers of science. In his discussion of the rise

of mathematical physics Heidegger argues that what was decisive was not a

high regard for o,bserved "facts," but the way in which nature or natural

processes were "mathematically projected." The projected concept of nature

(in mathematical terms) determines the kinds of facts which are relevant.

As Heidegger puts it, "the grounding of 'factual science' was possible only

because the researchers understood that in principle there are no 'bare

facts.' " it The totality of such "p~rojection" as characterizes mathematical

physics is, for Heidegger, thematizing (Thematisierung). Thematization is

objectification. What is understood o,r identified as subject to, mathematical

interpretation is no longer a neutral datum, but is already "constituted" by

the theoretical framework adopted. T o choose or to select a given theoretical

framework is to value that framework over other alternative modes of interpretation or explanation. The understanding of what is "there" presupposes

an implicit or explicit ontological commitment, a commitment which itself

cannot be justified in terms of the "facts" of "factual data" which are "discovered" on the basis of its assumption. The interpretation of a datum is

never purely presuppositionless. Although Heidegger would want to deny

that values lie at the basis of interpretation, I believe such a notion is not

entirely inconsistent with his view that

If, when o,ne is engaged in a particular co,ncrete kind of interpretations.., orte

likes to appeal to what "stands there," then o,ne finds that what "stands there" in

the first instance is nothing other than the obvious und.'isc~tssedassamaptton o6 the

persoaa who does the interpreting.iS

The question is, what is the source of such an "undiscussed assumption"?

If it is a theory, then that theory can be shown to have been selected or

chosen on the basis of some criterion or criteria which, in turn, can be

traced to a fundamental belief (e.g., in the uniformity of nature) which is

itself based upon a value-preference. To adopt the maxim of the uniformity

of nature, or the view that " . . . things similar in some respects tend to pro,ve

similar in others," is to adopt a vague notion of similarity which is itself

"relative to the structure of one's conceptual scheme or quality space." 19

Such phenomena are related to the value system of an individual (or,

usually, the value systems of a culture or a scientific community), Primitive

assumptions are very much like basic beliefs which we hold without any

absolute justification, but which are preferences which we find it difficult

16 Paul Feyerabend, "Explanation, Reduction and Empiricism.," in Minnesota

Studies in the Philosophy of Science, III, pp. 28-9.

17 Martin Heiclegger,Sein und Zeit, p, 362.

is 1bid., p. 150.

10 W. O. Quine, "On Simple Theories of a Complex World!," in Probability, Confirmation, and Simplicity, p.. 250.

Discussion

213

to abandon. Thus, for example, sub-atomic fields may or may not be symmetrical in actuality. But physicists tend to have a preferential disposition

to believe that, in fact, they are symmetrical. As Poincar6 put it, "scientists

think that certain facts are more interesting than others because they complete an unfinished harmony." e0 This quest for "harmony" and "symmetry"

may be charactea'ized as the valuational project of the scientist. So pervasive

can this phenomenon be that scientists, faced with emerging evidence that

historically valuable principles do not apply or seem to apply to specific

factual data, are unwilling to abandon such principles. When confronted

with indeterminacy in quantum physics Max Planck maintained that he

"firmly" believed that the quantum hypothesis would eventually result in a

"more exact formulation of the law of causality." 21 The desire to, preserve

a conceptual model of explanation in the face of contrary evidence suggests

an unwillingness to part with a valued ontological "projection."

Many philosophers of science are willing to admit the inevitability of the

intrusion of value judgments in the social sciences, but would exclude them

entirely from, say, the physical sciences. Karl Popper, for example, has said

that

where p~ed[lections and intere:sts have such influence on the content o~ scientific

theo,ries and predictiorts, it must become highly doubtful whether bias ca~ be

determined and avcrided. Thus we need not be saarprised to, find that there is very

little in the social sciences that resembles the ob~jectiveandi ideal quest for truth

which we meet in physies.:~e

In his R e a s o n and N a t u r e M. R. Cohen made a similar observation 2z by

suggesting that the social sciences should abandon their attempt to be

wertefrei. But surely there is some evidence that the physical sciences are

also infiltrated by valuations or value considerations as well. T o be sure,

some or the valuations of the physical scientist are intimately related to

existing knowledge or to purely scientific considerations. But, on the other

hand, certain epistemic preferences do reveal a commitment to extrascientific (often metaphysical) values. Thus, for example, it has been shown

that Helsenberg, in order to eliminate references to uno,bservable quantities,

"adopted" a phenomenological orientation which would eliminate from

physical theory whatever does not strictly correspond to observable entities

or phenomena.24 This proposal reflects a value preference which is not

adopted purely in terms of the data to be interpreted or in terms o~ the

theoretical structure o~ quantum mechanics. It is analogous to the adoption

of a behavioristic method in psychology in order to describe and explain

human behavior Values, in the broadest sense of the term, do indeed enter

so Henri Poincar6, The Value o] Science, New York, 1958, p,. 142.

zl Max Plauck, Where is Science Going?, New York, 1933, pp. 143, 155.

ze Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, New York, 1964, p. 16.

~3 Morris R. Cohen, Reason andNature, New York, 1953, p,. 349.

2~ Louis de Broglie, The Revolution in Physics, New York, 1953, p. 189.

214

The Journal of Value Inquiry

into the "objectivity" of the physical sciences. What is remarkable about this

phenomenon is that it is readily admitted by physical scientists despite the

denials of philosophers of science.:~ There are a number of non-factual

criteria which enter into the selection of theories or hypotheses, criteria

which are often reflections of dominant metaphysical, methodological,

personal, aesthetic, linguistic, or symbolic values. Very often extra-scientific

valuations involve the choice of a method of description or exp4anation

which is not an exact "fit" with the relevant facts. Pierre Duhem was well

aware of the phenomenon (~f selectivity and noted that quite often valued

symbolic formulae do not accurately describe what he called "practical

facts2' He maintained that there cannot be complete parity between an

abstract symbol and the concrete fact which it ostensibly represents. The

theoretical formulae which the physicist appeals to in order to "express" the

concrete facts he has observed in experimentation cannot be the exact

equivalent o~ these facts?6 Considerations of "simplicity," "neatness," or

"aesthetic uniformity" may be the non-factual criteria which "justify" the

abandonment o~ an exact correspondence between concrete facts and

theoretical description. It is clear that the acceptance of specific extrascientific criteria on the basis of implicit or explicit value preferences can

and does determine (a) what facts are relevant and (b) what factual data

will be ignored or bracketed in orrder that the non-factual criteria may be

satisfied. It is obvious that in such cases the significance o~ valuations for

the "structure" of scientific explanation or description cannot be ignored.

The factual data which are dealt with are not treated as if they were neutral

data, but are shaped and transformed by theoretical preferences which are, in

turn, determined by extra-scientific or non-factual criteria.

In regard to historical explanation it has been observed that accounts of

historical events are notoriously value-laden. Particular historical events are

selected as "significant" or discarded as "insignificant" and the personal or

cultural values of the historian deeply influence his judgments and descriptions of historical events. As M. R. Cohen has remarked,

the historian has to supplement the facts before him with hypothetical ones - in

which pro.ces,s he is obviously dependent on his general philosophy of life or

schema of relative value.., he must select from the great mass of facts those

which he considers most important, which again involves a process of valuation since importance is distinctly a category o~ value.27

One of the most revealing instances of valuation preferences in historical

explanation is found in the selection of causal factors which are considered

to be historically "relevant" or "significant." Whether the historian empha-

25 Cf. Erwin C. Schr,Sdirtger,Science, Theory, and Man, New York, 1957, Chapter

IV and p. 37.

e0 Pierre Duhem, The Aim and Structure of Physical Theory, New York, 1962,

p. 151.

~7 Morris R. Cohen, op. cit., p. 381.

Discussion

215

sizes "cultural," "political," "military," "geographical," "climactic," "philosophical," or "economic" factors will pervasively influence his interpretation, description, and evaluation of the "facts" which he selects and organizes. A subjective or culturally determined preference for mechanistic, or

teleological, or evolutionary accounts of historical developments will again

determine what [acta the historian thinks are relevant or what events are

significant. Value judgments or valuational preferences in historical explanation are ineluctable. Cultural values, not only influence the writing of

history, but clearly determine whether historical explanations, will or will not

be valued as such.

The Western valuation of the importance of history is obviously not universally shared by all peoples. India, for example, has been for the most part

an ahistorical nation. The significance of the concatenation of events in the

human world has simply not been recognized. It has been noted that

the cultures of the East... belittle man as individual man. Und!er this runs an

indifference to. the wo,rld of the senses, of which the indifference to experienced

fact is one face... These cultures of the East... lack the language artdi the very

habit of fact.2s

The "habit of fact" is perhaps the most universally shared value in the

Western world; it is the universal determination of any possible act of understanding or interpretation. It is obviously a value which cannot be justified

by an appeal to "objective data," but can only be justified in terms of some

practical or teleological value. That facts, or factual data are recognized or

considered as of worth or value indicates the most universal way in which

values infiltrate any attempt to achieve a purely neutral understanding or

description of objective phenomena. Even if we do adopt a factual orientation towards the world or towards human actions the scientific description

and selection of facts is not possible, as we have seen, without some appeal

to extra-scientific or non-factual values.

When considering what will count as relevant data we cannot only rely

on the historical development of science o.r the alleged neutrality of facts;

rather, as has recently been said, we must reconstrue the concept of data in

such a way as to incorporate the prospective aspect of the world "presently

apprehended as value." 29 It is not necessary to collapse the distinction

between facts and values in order to become, aware of the influence of values

upon factual judgments, to admit that, in a sense, the value-laden character

of factual data (or facta) is part and parcel of the scientific or empirical

enterprise. Factual data can, in some cases, clearly be distinguished from

values; but values cannot be wholly divorced from our understanding and

interpretation of factual data. The intelligiNlity of phenomena is not

"given"; hence, there is an inevitable interpretative element in philosophy as

well as science. Insofar as interpretation is necessary for understanding or

2s j. BronowskL Science and Human Values, New York, 1956, p. 43.

e9 Peter Caws, op. cit., p. 75.

216

The Journal of Value Inquiry

intelligibility, human knowledge cannot be entirely accounted for without

referring to the influence of valuations. Facts are not literally identical with

values, but are related to values, are intelligible in terms of value-laden interpretations. In this sense, factual data are "structured" in terms of individual

or cultural values, cultural posits or sets.

The alleged epistemic neutrality of scientific fact or of facts in general

may be called, in Kantian language, an ideal of reason; but it is not an

actuality. The bifurcation between facts and values which is o,flen supported by radical empiricists (especially logical positivists) is clearly an

exaggeration, one which neglects the obvious influence of valuation upon

a generalized factual orientation, the selectivity of factual data, and the

significance of facts themselves. The judgment that x is a fact requires, as

I have said, interpretation; and all interpretation, as Nietzsche once pointed

out, is fundamentally value-interpretation. We need not abandon a distinction which has a pragmatic value; but, on the other hand, we must no,t

be led to believe that facts and values are not interrelated, that facts are not

value-laden. For, this leads to an inevitable empirical dogmatism which is

surely as pernicious as the aprioristic dogmatism it intended to overcome.

S.U.N.Y. College at Brockpo,rt

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Brain CureDocument157 pagesBrain CureJosh BillNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Newspaper TemplateDocument6 pagesNewspaper TemplatemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Newspaper TemplateDocument6 pagesNewspaper TemplatemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Interview SkillsDocument36 pagesInterview SkillsManish Singh100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 1999 Oliver Whence Consumer LoyaltyDocument13 pages1999 Oliver Whence Consumer LoyaltyDevanto Reiga100% (1)

- Social-Emotional Outcome GoalDocument3 pagesSocial-Emotional Outcome GoalnvNo ratings yet

- VYGOTSTKY, L. (The Collected Works of L. S) Problems of The Theory and History of Psychology (1997, Springer US) PDFDocument424 pagesVYGOTSTKY, L. (The Collected Works of L. S) Problems of The Theory and History of Psychology (1997, Springer US) PDFVeronicaNo ratings yet

- Mass Media and CultureDocument7 pagesMass Media and CultureNimrodReyesNo ratings yet

- Schutz - Concept and Theory Formation in The Social SciencesDocument17 pagesSchutz - Concept and Theory Formation in The Social SciencesmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Classification of Social ProcessDocument31 pagesClassification of Social ProcessIrish Mae T. Espallardo50% (2)

- Andrew Kap - Just Feel GoodDocument80 pagesAndrew Kap - Just Feel Goodtradingaop100% (1)

- The Concept of Work Life Balance EssayDocument10 pagesThe Concept of Work Life Balance EssaySoni Rathi100% (1)

- Nietzsche's Critique of Positivism - Existence and The OneDocument16 pagesNietzsche's Critique of Positivism - Existence and The OnemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Social OntologyDocument771 pagesSocial OntologyJoey Carter100% (1)

- ATA585-2017Fall SyllabusDocument4 pagesATA585-2017Fall SyllabusmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Kantianism - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocument12 pagesKantianism - Britannica Online EncyclopediamehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Mind Volume 21 Issue 81 1912 (Doi 10.2307/2248912) Review by - F. C. S. Schiller - Die Philosophie Des Als Ob. System Der Theoretischen, Praktischen Und Religiosen Fiktionen Der Menschheit Auf GrundDocument13 pagesMind Volume 21 Issue 81 1912 (Doi 10.2307/2248912) Review by - F. C. S. Schiller - Die Philosophie Des Als Ob. System Der Theoretischen, Praktischen Und Religiosen Fiktionen Der Menschheit Auf GrundmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Liberal Arts Speech8Document16 pagesLiberal Arts Speech8mehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Bulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsDocument11 pagesBulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Zuckert, Nature, History, and The Self - Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations - History - Historicism PDFDocument16 pagesZuckert, Nature, History, and The Self - Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations - History - Historicism PDFmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Ash - The Emergence of Gestalt Theory - Experimental Psychology in Germany, 1890-1920 - PHD ThesisDocument661 pagesAsh - The Emergence of Gestalt Theory - Experimental Psychology in Germany, 1890-1920 - PHD Thesismehmetmsahin100% (1)

- Bulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsDocument11 pagesBulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- July 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishDocument24 pagesJuly 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- July 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishDocument24 pagesJuly 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Otto Bird - The Re-Discovery of The TopicsDocument7 pagesOtto Bird - The Re-Discovery of The TopicsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Strauss ModernitysThreeWavesDocument9 pagesStrauss ModernitysThreeWavesV_ctor_Manuel__7561No ratings yet

- Otto Bird - The Tradition of The Logical Topics - Aristotle To OckhamDocument18 pagesOtto Bird - The Tradition of The Logical Topics - Aristotle To OckhammehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- İlhan Uzgel, "Between Praetorianism and Democracy The Role of The Military in Turkish Foreign Policy", The Turkish YearbookDocument35 pagesİlhan Uzgel, "Between Praetorianism and Democracy The Role of The Military in Turkish Foreign Policy", The Turkish YearbookmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Syrians in Turkey The Economics of IntegrationDocument10 pagesSyrians in Turkey The Economics of IntegrationmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Sayyid On Rituals Ideals and Reading The QuranDocument4 pagesSayyid On Rituals Ideals and Reading The QuranmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Ps 589 - State Formation and Political Regimes - Syllabus - Fall 2014Document20 pagesPs 589 - State Formation and Political Regimes - Syllabus - Fall 2014mehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Walton - Beyond Convivencia and Conflict - Reflections On The History and Memory of Andalusian and Ottoman Religious BelongingDocument7 pagesWalton - Beyond Convivencia and Conflict - Reflections On The History and Memory of Andalusian and Ottoman Religious BelongingmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Tastan - Gezi Park Protests in Turkey: A Qualitative Field ResearchDocument12 pagesTastan - Gezi Park Protests in Turkey: A Qualitative Field ResearchmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Baber Johansen - Islamic Modernism (1) HDS2014FallIslModernisCorrFinVersSept15Document4 pagesBaber Johansen - Islamic Modernism (1) HDS2014FallIslModernisCorrFinVersSept15mehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Critique of DuerrDocument6 pagesCritique of DuerrmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- The Heythrop Journal Volume 48 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00315.x) Benjamin D. Crowe - Nietzsche, The Cross, and The Nature of GodDocument17 pagesThe Heythrop Journal Volume 48 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00315.x) Benjamin D. Crowe - Nietzsche, The Cross, and The Nature of GodmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Dhaouadi - Interview With Smelser - Social Sciences in CrisisDocument8 pagesDhaouadi - Interview With Smelser - Social Sciences in CrisismehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Ernst Kantorowicz Humanities and HistoryDocument3 pagesErnst Kantorowicz Humanities and HistorymehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Kajal JainDocument96 pagesKajal JainAnil BatraNo ratings yet

- Aquinas AbstractionDocument13 pagesAquinas AbstractionDonpedro Ani100% (2)

- Pedagogy Solved MCQs (Set-6)Document6 pagesPedagogy Solved MCQs (Set-6)himanshu2781991No ratings yet

- Modified Literacy Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesModified Literacy Lesson Planapi-385014399No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Development Test 2 Assessment SheetDocument7 pagesEntrepreneurship Development Test 2 Assessment SheetHaseeb ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Project Report On " Efects of Celebrity Endorsement On Consumer Behaviour "Document46 pagesProject Report On " Efects of Celebrity Endorsement On Consumer Behaviour "Jaimini PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Wayne 1997Document31 pagesWayne 1997agusSanz13No ratings yet

- MST Ass.Document6 pagesMST Ass.Marc Armand Balubal MaruzzoNo ratings yet

- Zimet1988 PDFDocument13 pagesZimet1988 PDFMarta ParaschivNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document23 pagesModule 2Elizabeth ThomasNo ratings yet

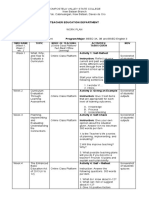

- DM 241 Set 1Document17 pagesDM 241 Set 1damcelletNo ratings yet

- Assessment Centres and Development Centres: Managerial CentersDocument24 pagesAssessment Centres and Development Centres: Managerial Centersdarff45No ratings yet

- Our Lady of Mount CarmelDocument2 pagesOur Lady of Mount CarmelJonathan BarneyNo ratings yet

- Introducing and Naming New Products and Brand ExtensionsDocument16 pagesIntroducing and Naming New Products and Brand ExtensionsHUỲNH TRẦN THIỆN PHÚCNo ratings yet

- Module Week 4 UCSPDocument5 pagesModule Week 4 UCSPMary Ann PaladNo ratings yet

- Evidence 2 Effective PresentationsDocument4 pagesEvidence 2 Effective Presentationslupita andradeNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan The Happiest Boy in The WiorldDocument10 pagesLesson Plan The Happiest Boy in The WiorldCzarinah PalmaNo ratings yet

- Review of Factors Influencing The Coach-Athlete Relationship in Malaysian Team SportsDocument22 pagesReview of Factors Influencing The Coach-Athlete Relationship in Malaysian Team SportsWan Muhamad ShariffNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Decision Sciences MSCDocument4 pagesCognitive Decision Sciences MSCasdasdasdNo ratings yet

- HG Learner's Development AssessmentDocument3 pagesHG Learner's Development AssessmentTabada NickyNo ratings yet

- (Week 1, Week 2, Etc ) (Online Class Platform/ Text Blast/ Offline Learning)Document3 pages(Week 1, Week 2, Etc ) (Online Class Platform/ Text Blast/ Offline Learning)Joy ManatadNo ratings yet