Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Psych Journal

Uploaded by

pa3kmedinaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Psych Journal

Uploaded by

pa3kmedinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Development and Evaluation of a Guideline

for Nursing Care of Suicidal Patients

With Schizophrenia ppc_239 65..73

Esther L. Meerwijk, RN, MSc, Berno van Meijel, RN, PhD, Jan van den Bout, PhD, Ad Kerkhof, PhD,

Wim de Vogel, RN, and Mieke Grypdonck, RN, PhD

PURPOSE. The purpose of this study was to Esther L. Meerwijk,* RN, MSc, is a Doctoral Student at

the University of California San Francisco, School of

develop and test an evidence-based guideline that Nursing, San Francisco, CA, USA; Berno van Meijel,

RN, PhD, is a Professor of Mental Health Nursing and

would support nursing care for suicidal patients

Director of the Research Group Mental Health Nursing,

with schizophrenia. INHolland University for Applied Sciences, Amsterdam,

The Netherlands; Jan van den Bout, PhD, is a Professor of

DESIGN AND METHODS. Systematic review of the Clinical Psychology, Department of Clinical and Health

Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The

literature and consultation of experts preceded

Netherlands; Ad Kerkhof, PhD, is a Professor of Clinical

completion of the guideline. Twenty-one nurses Psychology, Psychopathology and Suicide Prevention,

Department of Clinical Psychology, EMGO+ Institute,

from two mental health institutions tested the Vrije University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Wim de

Vogel, RN, is Team Leader, Center of Expertise on

guideline for feasibility in nursing practice.

Psychotic Disorders, Dimence Mental Health Care Center,

FINDINGS. The guideline was found to support Deventer, The Netherlands; Mieke Grypdonck, RN, PhD,

is a Professor of Nursing Science, Julius Center for Health

discussing suicidality with patients and Sciences and Primary Care, Department of Nursing

Science, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The

assessing suicide risk. Participants endorsed

Netherlands.

implementation of the guideline in mental

health care. D iscussing suicidality and assessing suicide risk

are challenges mental health nurses face in their

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS. Nurses who care for

care of patients with schizophrenia. Evidence-based

patients with schizophrenia are advised to use guidelines are available that support the care for

patients with schizophrenia (American Psychiatric

this guideline as a foundation for their care. Association, 2004; National Steering Committee on

Multidisciplinary Guideline Development in Mental

Search terms: Guideline, nursing assessment,

Health Care, 2005) and for suicidal patients in general

schizophrenia, suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2003). However,

aspects of nursing care for suicidal patients with

schizophrenia are addressed only to a limited extent

in these guidelines.

Suicidality, which is defined here as any thought or

action that relates to a self-inflicted death, is a frequent

* Previously, Junior Researcher, Julius Center for Health phenomenon among patients with schizophrenia.

Sciences and Primary Care, Department of Nursing According to the Practice Guideline for the Assessment

Science, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors (Ameri-

Netherlands. can Psychiatric Association, 2003), 40–53% of patients

First Received February 13, 2009; Final Revision received July 7, with schizophrenia think about suicide at some point

2009; Accepted for publication July 23, 2009. in their lives, and 23–55% actually engage in a suicide

Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010 65

Development and Evaluation of a Guideline for Nursing Care of Suicidal Patients With

Schizophrenia

attempt. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia licensed practical nurses with respect to: (a) discussing

is estimated to be about 5% (Palmer, Pankratz, & suicidality with the patient, (b) assessing suicide risk,

Bostwick, 2005). These figures indicate that mental and (c) selecting and performing appropriate nursing

health nurses who take care of patients with schizo- interventions. Through enhancing nursing compe-

phrenia are likely to be confronted with patients who tence, it is expected that the guideline will contribute

are thinking about suicide and demonstrate suicidal to filling the patients’ needs to discuss suicidality,

behavior. and to improved assessment of suicide risk. It is also

Mental health nurses often do not actively discuss expected that the guideline will contribute to work

suicidal thoughts with their patients. In a study by satisfaction of nurses because of enhanced competence

Talseth, Lindseth, Jacobsson, and Norberg (1999), in caring for suicidal patients.

nurses at a psychiatric inpatient unit often avoided the This article describes the development of the guide-

subject, although their suicidal patients expressed a line and provides a brief overview of the guide-

need for them to be present and listen. Another study line itself. In addition, the results of a pilot study

reported that psychiatric nurses need more training in are presented. The purpose of this pilot study was to

verbal communication skills with respect to discussing evaluate the guideline for clinical usability in nursing

suicidality (McLaughlin, 1999). Sun, Long, Boore, and practice.

Tsao (2005) reported a need for advanced communica-

tion qualities to effectively assess suicidal patients and Guideline Development

maintain a therapeutic relationship. A need for training

with respect to risk assessment leading to evidence- The objective was to develop a nursing practice

based interventions and meaningful responses to guideline based on existing evidence and best prac-

people who are suicidal was also expressed by tice. Therefore, a literature review was conducted

Cutcliffe and Stevenson (2008). using suicide, risk factor, risk assessment, and schizophre-

During personal communication of one of the nia as search terms. Literature databases that were

authors with nurses from the field, nurses mentioned accessed included: Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, Psy-

emotional unrest caused by the lack of a standard of cINFO, and Cochrane. English literature concerning

care for the suicidal patient. This appeared to be reviews and intervention studies published between

especially true shortly after a patient committed or 1990 and June 2007 was included. Exclusion criteria

attempted suicide. Suicidality is a subject that neither were medication studies, articles about biological

nurses nor patients bring up easily. However, by avoid- psychiatric topics, and articles concerning child and

ing the subject, patients are left with tormenting adolescent populations. Literature that remained after

thoughts. This adds to feelings of isolation, which is a application of these criteria provided the basis for an

major problem in patients with schizophrenia (Ameri- initial draft of the guideline. The most important

can Psychiatric Association, 2004). sources of literature used to develop the guideline

Because no evidence-based guideline existed to were the Practice Guideline for the Assessment and

support nurses in their care for suicidal patients with Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors (American

schizophrenia, a guideline was developed and tested. Psychiatric Association, 2003) and a systematic review

The general purpose of this guideline was to enhance of risk factors for suicide and schizophrenia by

mental health nurses’ competence to provide care Hawton, Sutton, Haw, Sinclair, and Deeks (2005).

to suicidal patients with schizophrenia or related Dutch literature was used as well for the initial draft,

psychotic disorders. More specifically, the aim of in particular the Dutch Multidisciplinary Guideline

the guideline was to support registered nurses and Schizophrenia (National Steering Committee on

66 Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010

Multidisciplinary Guideline Development in Mental guideline promotes to assess suicidality in a naturally

Health Care, 2005). flowing conversation rather than by asking items from

The guideline, Nursing Care of Suicidal Patients with a standard instrument. These important underlying

Schizophrenia or Related Psychotic Disorders, consists of: principles for the SAs were supported by a multidisci-

(a) part A: theoretical background and recommenda- plinary panel of experts selected on the basis of indi-

tions, (b) part B: data collection and interventions, (c) vidual experience with suicidality and schizophrenia.

basic suicidality assessment (SA), and (d) advanced This panel comprised four mental health nurse special-

SA. Parts A and B provide background information ists, four patients from a patient support organization,

and instructions for usage. The basic SA and advanced a psychiatrist, and a psychologist.

SA are working documents that nurses can use in clini- In order to support nurses in their communication

cal practice. In order to meet current standards, the with patients, the basic SA and advanced SA contain

guideline was set up to comply with the AGREE instru- examples of questions and phrases that can be used

ment for the appraisal of guidelines (The AGREE when discussing suicidality with patients. It is essen-

Collaboration, 2001). tial that nurses adapt these examples to their personal

Part A of the guideline is predominantly derived communication style, the actual situation of the patient,

from the Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treat- and their specific relationship with the patient. Further-

ment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors (American Psy- more, both assessments provide the opportunity to

chiatric Association, 2003) and provides information on score risk factors on an ordinal scale ranging from 0 to

risk factors for suicide in the general population, risk 2, with 0 indicating the absence of a risk factor, and 2

factors for suicide in patients with schizophrenia, and indicating the presence of a risk factor.

on psychiatric management of patients who suffer The basic SA uses several items from the Scale for

from suicidality. Part A concludes with general recom- Suicide Ideation (Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979) and

mendations for clinical practice. In part B, these recom- provides a means to establish suicidality relatively

mendations are translated into a guideline specifically quickly. Topics include: quality of life; reasons for

for nursing practice. Part B describes the underlying living; reasons for not wanting to live; and suicidal

principles and conditions in order to use the basic SA thoughts, behavior, and intent. The following example,

and the advanced SA effectively. Furthermore, part B of taken from the basic SA, illustrates the kind of ques-

the guideline describes how suicide risk is evaluated tions and the principle of scoring the risk factors.

from the information collected and how nurses can

intervene to reduce the risk for suicide and improve Have you ever felt the desire to harm yourself, for

the patient’s quality of life. instance by taking a lot of drugs or dangerous

The basic SA and advanced SA are constructed behavior in traffic?’

around the evidence-based risk factors and protective Has the patient recently felt the desire to attempt

factors for suicide as described in part A of the guide- suicide (either active or passive)?

line. Nurses are encouraged to discuss suicidality 0. no

openly, with an accepting and empathic attitude 1. yes, weakly

(American Psychiatric Association, 2003; Talseth et al., 2. yes, strongly

1999), and patients must feel that speaking about sui-

cidality is acceptable and can be done without fear of The advanced SA is used only when a nurse actu-

judgment. From the notion that nurses should be non- ally knows a patient suffers from suicidality, or when

judgmental follows that suicide should not be com- the basic SA leads to the conclusion that this might be

pletely rejected as an option to the patient. The the case. Contrary to the basic SA, the advanced SA is

Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010 67

Development and Evaluation of a Guideline for Nursing Care of Suicidal Patients With

Schizophrenia

geared toward schizophrenia and explores suicidality viewed as a group. Topics for these interviews were:

and schizophrenia-related issues in more detail. The the specific content of the guideline, potential of the

advanced SA covers the following domains: (a) guideline to achieve the intended goals, clinical usabil-

suicidal thoughts and behaviors, (b) consequences of ity of the guideline, and clarity and readability of the

schizophrenia, (c) psychosocial factors, (d) psycho- guideline. The interviews were audiotaped and tran-

logical and cognitive factors, (e) substance abuse, and scribed for analysis.

(f) physical disorders. The objective of the advanced A qualitative analysis of the interview transcrip-

SA is to enable a more accurate assessment of suicid- tions was performed. Suggestions for modification of

ality and suicide risk, and to obtain patient informa- the guideline were assigned a level indicating the

tion that will enable development of a patient-tailored necessity for modification (level 1: compulsory; level

suicide intervention plan. This intervention plan 2: will improve the guideline; level 3: suggested but

aims to support the patient in coping with his or her not required). Members of the expert panel could

suicidal thoughts and to improve the patient’s quality review suggestions made by all other panel members

of life. and provide feedback on the modifications as pro-

Evidence for effective nursing interventions is posed by the authors. Based on feedback of the expert

lacking for suicidal patients with schizophrenia. There- panel, a revised version of the guideline was pre-

fore, the interventions in the guideline are based on pared for the pilot study. The same panel of experts

what is described in other guidelines (American Psy- reviewed the final version of the guideline, which

chiatric Association, 2003; National Steering Commit- included modifications based on results from the

tee on Multidisciplinary Guideline Development in pilot study.

Mental Health Care, 2005) and what was considered

good clinical practice according to members of the Pilot Study Method

expert panel. Interventions with respect to safety of

patients include: keep contact regularly, make clear The pilot study involved 21 mental health nurses

when you will see or contact the patient again, limit and community mental health nurses from two purpo-

access to lethal means, set up a crisis response plan sively selected mental health institutions in The Neth-

(Rudd, Mandrusiak, & Joiner Jr., 2006), and consider erlands: one located in a large city, and the other in

admission to an inpatient unit. Other interventions a rural area of the country. After approval from the

include: provide psycho-education, assist in activities institutions’ medical and ethical review boards was

of daily living, mobilize social support system, support obtained, nurses from eight inpatient and outpatient

in solving problems, and provide education about units self-selected to participate in the pilot study. The

rehabilitation programs and buddy programs. Because average experience of the nurses with suicidal patients

of the severe nature of suicidality, it is of paramount was 11.2 years (SD = 7.2 years).

importance that co-workers in nursing and other dis- During two half-day sessions, participating nurses

ciplines are consulted to discuss appropriate interven- from both institutions were trained to use the guide-

tions in order to guarantee that the best possible care is line. Subsequently, they used the guideline to conduct

given. SAs and develop suicide intervention plans for

The initial draft of the guideline was reviewed for patients from their caseloads, during a period of 5

validity and completeness by the panel of experts. months. The completed SAs and intervention plans

Semistructured interviews were conducted with the were collected. Group interviews with the nurses were

professional experts on an individual basis. The conducted twice at both locations: halfway and at the

patients who took part in the expert panel were inter- end of the 5-month period. These interviews were

68 Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010

Table 1. Nurses’ (n = 17) Responses to the Pilot Test Questionnaire

M

(range 1–5)* SD

Discussing suicidality with patients

The guideline supports discussing suicidality. 4.00 1.06

The example questions and phrases in the basic suicidality assessment (SA) 3.82 1.02

are useful.

The example questions and phrases in the advanced SA are useful. 3.59 1.00

Because of the guideline, I am more active in discussing suicidality. 3.06 0.90

Assessment of suicide risk

The guideline supports assessment of suicide risk. 3.94 0.56

The guideline enables assessment of suicide risk 3.35 0.79

Selecting and performing interventions

The guideline supports in selecting interventions. 3.53 0.80

The guideline supports in performing interventions. 3.12 0.70

Using the guideline results in appropriate interventions. 3.38 0.72

Using the guideline results in interventions that are realistic and attainable. 3.41 0.71

Usability of the guideline

I would recommend this guideline for nursing practice. 3.76 0.97

The basic SA is usable at my institution. 3.76 1.03

The advanced SA is usable at my institution. 3.41 0.94

Part A contains useful background information. 3.88 0.86

The guideline improved my caring for suicidal patients. 3.00 0.87

Secondary outcomes of the guideline

The guideline improved my caring for family and friends of suicidal patients. 2.69 0.60

Because of the guideline, the communication between nurses and patients has 2.76 0.66

improved.

Because of the guideline, interdisciplinary communication about suicidality 2.65 0.61

has improved.

*1, do not agree at all; 2, do not agree; 3, do not agree/agree; 4, agree; 5, fully agree.

audiotaped and summarized for analysis purposes. Pilot Study Results

The summaries focused on topics relevant to usability

of the guideline, observed patients’ responses, and The number of SAs and intervention plans com-

implementation issues with respect to current practice. pleted during the pilot study are shown in Table 2.

Content analysis of the interview summaries, SAs, and From this table, it can be seen that the basic and

intervention plans was performed. advanced SA and intervention plans were not

In addition to these qualitative data, quantitative completed by all nurses. The reasons nurses men-

data were collected by means of a questionnaire (see tioned for not applying the guideline were positive

Table 1) that the nurses filled in after the pilot study. A symptoms of schizophrenia and low verbal intelli-

symmetrical 5-point Likert scale was used ranging gence of the patients, which hindered communica-

from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (fully agree). tion. Furthermore, the nurses thought it better to

Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010 69

Development and Evaluation of a Guideline for Nursing Care of Suicidal Patients With

Schizophrenia

Table 2. Number of Suicidality Assessments (SAs) factors for suicide and tended to respond more thor-

and Intervention Plans That Were oughly to patient symptoms indicative of suicidality.

Developed Based on the Guideline During They scored slightly above neutral about whether

the Pilot Study the guideline made them more active in discussing

suicidality (rating 3.06). The nature of the items in

Done by both SAs enabled discussion with patients. The use-

Total number

number of nurses

fulness of the example questions and phrases in the

assessments was rated quite positively at 3.82 and

Basic SAs 37 15 3.59 for the basic SA and advanced SA, respectively.

Advanced SAs 14 9 Memorizing the items enabled the nurses to integrate

Intervention plans 4 4 them into a natural conversation. The overall poten-

tial of the guideline to support nurses in discussing

suicidality with patients is reflected in a rating

of 4.0.

refrain from assessing suicidality when patients were From the interviews, it became clear that some

focusing on rehabilitation (e.g., restoring independent nurses experienced difficulty in adapting the wording

living, employment, study). of the example questions and phrases to their personal

During the interviews, nurses indicated that the communication style and the actual situation of the

patients’ responses to application of the guideline patient. The interviews also made clear that many

were very positive. Although speaking about their nurses did not discuss suicidality with patients if there

suicidality had not been easy for the patients (more were no apparent signs of suicidality. In fact, some

than once they reacted emotionally to the questions), nurses mentioned that they found it difficult to ask a

they expressed appreciation for having been given patient about suicidal thoughts if there were no clear

the opportunity to talk about suicidality and related signs of suicidality.

issues. One patient responded that it was the first

time someone had asked about suicidal thoughts, and Assessing Suicide Risk

that he had found it difficult to bring up the issue

himself. The ratings from the questionnaire with respect to

Seventeen of the participating nurses filled in assessment of suicide risk were 3.94 for “the guideline

the questionnaire after the pilot study. Table 1 supports assessment of suicide risk” and 3.35 for “the

shows their responses (average ratings and standard guideline enables assessment of suicide risk.” During

deviation). The remainder of the results of the the interviews, the nurses did not mention any diffi-

pilot study are described in relation to the topic areas culty assessing suicide risk.

that were covered by the questionnaire. Where appli-

cable, average questionnaire ratings are indicated in Selecting and Performing Interventions

the text.

Because only four nurses developed an interven-

Discussing Suicidality with a Patient tion plan based on the guideline, interventions were

not discussed in detail during the interviews. Some

The interview data revealed that the guideline nurses mentioned that they did develop an interven-

made nurses more aware of the issue of suicidality. tion plan, but that it was structured in accordance

Nurses mentioned that they were more alert to risk with the format used within their organization. These

70 Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010

intervention plans were not part of the data that were Secondary Outcomes of the Guideline

collected for the pilot study.

The quantitative data showed that the nurses were The nurses were mostly positive about the primary

positive about the interventions in the guideline and aims of the guideline, but they were moderate about its

the proposed procedure of selecting appropriate inter- perceived effect on their ability to provide care to

ventions (3.38–3.53), although they had not all had the family and friends of suicidal patients (2.69). Quantita-

opportunity to actually develop an intervention plan. tive data did not show perception of improvement in

The potential of the guideline to support in the actual general communication between patients and nurses

performance of the interventions was rated only (2.76), nor in interdisciplinary communication about

slightly less at 3.12. suicidality (2.65).

Usability of the Guideline Discussion and Conclusion

Although there was considerable spread in opinions A practice guideline for nursing care of suicidal

about usability, the overall rating of the nurses who patients with schizophrenia or related psychotic disor-

expressed their opinions about implementing the ders was developed and tested. The guideline is

guideline in mental health nursing practice was posi- grounded in available evidence about risk manage-

tive (rating 3.76). From the interviews, it became clear ment and best practice interventions to reduce suicide

that the nurses were especially positive about the basic risk. Using the assessments included in the guideline

SA. This appreciation can also be seen in the ratings assures that all issues relevant to suicide risk are

about the assessments’ usability within their institu- covered when discussing suicidality with a patient. The

tions, which were 3.76 and 3.41 for the basic and level of detail of these assessments exceeds standard

advanced SA, respectively. questions about suicidality. They allow for an open

Another finding from the interviews was that many discussion with the patient, with ample opportunity

nurses experienced difficulty to apply the guideline to for the patient to discuss personal experiences. The

all patients with schizophrenia or related psychotic guideline furthermore discusses interventions to

disorders. They stated very strongly that the guideline reduce suicide risk and improve the patient’s quality

is better not used with patients with comorbid person- of life.

ality disorders or mental retardation. Because suicidal- The results of the pilot study show the potential of

ity is so explicitly the subject of the assessment, nurses the guideline to support nurses in discussing suicidal-

feared that this would trigger or increase suicidal ity with patients and assessing suicide risk, and to a

thoughts in these patients. lesser extent, the potential to support selection and

Some nurses questioned the necessity of the guide- execution of interventions. The level of experience of

line. In their opinion, the guideline was not in any the nurses who participated in the pilot study was

respect new. They mentioned that they already dis- quite high. This may explain why some of the partici-

cussed suicidality during regular contacts as a primary pating nurses experienced the guideline as nothing

caregiver of the patient. About half of the participating new. It is possible that the guideline makes explicit

nurses believed the guideline to be especially useful what some nurses already do based on experience. The

for nurses with little experience in this area of psychi- guideline received less support for selection and

atric nursing. They were moderate about the effect of execution of interventions, which may be a result of

the guideline on their personal ability to provide care having had few opportunities to develop an interven-

to suicidal patients (rating 3.00). tion plan based on the guideline. According to the

Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010 71

Development and Evaluation of a Guideline for Nursing Care of Suicidal Patients With

Schizophrenia

nurses, the main reason for these few opportunities provides patients with an opportunity to express their

was the perceived absence of suicidality among feelings about suicidal thoughts and behaviors, which

patients that were in care during the pilot study. In may in fact be a relief to them and make them feel

addition, the majority of nurses in one institution had understood and recognized. It would be worthwhile to

to draw from the same pool of patients, which reduced investigate the motives of nurses who are reluctant to

the number of candidates. discuss suicidality with patients who do not bring up

However, there may be another explanation for the this issue themselves.

relatively few assessments and intervention plans. The only international data-based publication on the

Many nurses indicated that they normally do not nurse’s role in assessing suicide risk to compare our

discuss suicidality with patients if there are no appar- guideline with is the Nurses’ Global Assessment of

ent signs of suicidality. This raises the question of Suicide Risk (Cutcliffe & Barker, 2004), which is a scale

which signs should be apparent to make them ask that enables quick assessment of suicide risk. Like our

about suicidality. Moreover, nurses sometimes feared guideline, it is evidence based, but it does not discuss

that discussing suicidality may actually trigger suicidal how information about the patient is best obtained, nor

thoughts and may increase suicidal intent and behav- does it provide interventions that can be performed.

ior. Some nurses mentioned that their patients focused There are some limitations that should be taken into

on rehabilitation. This may have led these nurses to consideration when interpreting the results of this

assume that suicidality would not be an issue for these study. First, the instances in which nurses were able

patients, which is not necessarily a valid assumption to apply the complete guideline, that is, basic SA,

because suicide risk increases immediately after hospi- advanced SA, and intervention plan, were few. As a

tal discharge (Troister, Links, & Cutcliffe, 2008). result, not every nurse who participated in the pilot

Overall, it appears that nurses are reluctant to discuss study had been able to evaluate the complete guideline

suicidality when patients do not bring up the issue in clinical practice. Some nurses who filled in the ques-

themselves. It seems they prefer to “let sleeping dogs tionnaire had not had the opportunity to use (all parts

lie,” rather than consider the consequences of avoiding of) the guideline.

the issue for a patient who is indeed suffering from Second, the group interviews did not allow for con-

suicidality. clusions based on consensus among the nurses. Some-

The nursing discipline is not the only discipline that times, it was clear that the majority of the nurses

appears to avoid discussing suicidality with at-risk agreed with a particular statement, but other issues

patients. Similar results were reported among physi- clearly applied to the specific situation of an individual

cians (Feldman et al., 2007; Stoppe, Sandholzer, nurse. Another aspect of the group interviews that may

Huppertz, Duwe, & Staedt, 1999). Feldman et al. (2007) have affected the results is that one group consisted

also mentioned the idea that talking about suicidal almost entirely of a single team of nurses working at

thoughts and behavior increases their severity. the same unit. Their team culture may have had a dis-

However, there is no evidence to support this idea proportionately large effect on the data, masking the

(Williams, Noel, Cordes, Ramirez, & Pignone, 2002). opinion of individual nurses.

The little evidence that does exist points to the opposite We conclude that the pilot study shows the potential

(Gould et al., 2005). Moreover, the Practice Guideline for of the guideline to support nurses in discussing suicid-

the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal ality with patients and in assessing suicide risk. Nurses

Behaviors states that discussing suicidality does not who participated in the pilot study were positive in

“plant the issue in the patient’s mind” (American Psy- their advice to implement this guideline in mental

chiatric Association, 2003, p. 19). Raising the topic health care.

72 Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010

Implications for Nursing Practice Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 11, 393–400. doi:

10.1111/j.1365-2850.2003.00721.x

Cutcliffe, J. R., & Stevenson, C. (2008). Never the twain? Reconciling

Although the guideline may be very useful for national suicide prevention strategies with the practice, educa-

nurses with little experience in caring for suicidal tional, and policy needs of mental health nurses (Part one).

International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17, 341–350.

patients, it is our perception that experienced nurses doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00557.x

who care for patients with schizophrenia can also Feldman, M. D., Franks, P., Duberstein, P. R., Vannoy, S., Epstein, R.,

benefit from the guideline. Using the guideline as a & Kravitz, R. L. (2007). Let’s not talk about it: Suicide inquiry in

primary care. Annals of Family Medicine, 5, 412–418. doi: 10.1370/

standard of care asserts that issues relevant to suicide afm.719

risk are covered, and it prevents nurses from becoming Gould, M. S., Marrocco, F. A., Kleinman, M., Thomas, J. G.,

overconfident about a phenomenon that is complex in Mostkoff, K., Cote, J., et al. (2005). Evaluating iatrogenic risk of

youth suicide screening programs: a randomized controlled

nature and can have as far-reaching consequences as trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293, 1635–

suicidality. Training in using the guideline should 1643.

dedicate ample time to adapting the example phrases Hawton, K., Sutton, L., Haw, C., Sinclair, J., & Deeks, J. J. (2005).

Schizophrenia and suicide: Systematic review of risk factors.

and questions of the SAs to one’s personal communi- British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 9–20.

cation style in order to enable integration in a naturally McLaughlin, C. (1999). An exploration of psychiatric nurses’ and

flowing conversation. Furthermore, during training, it patients’ opinions regarding in-patient care for suicidal patients.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29, 1042–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-

must be communicated that there is no scientific evi- 2648.1999.01000.x

dence to support the idea that discussing suicidality National Steering Committee Multidisciplinary Guideline Develop-

triggers or increases suicidal thoughts, intent, or ment in Mental Health Care. (2005). Multidisciplinaire richtlijn

schizofrenie [Multidisciplinary guideline schizophrenia]. Utrecht:

behavior. Coaching and intervision/supervision may Trimbos.

be required to further enhance successful implementa- Palmer, B. A., Pankratz, V. S., & Bostwick, J. M. (2005). The lifetime

tion of the guideline. risk of suicide in schizophrenia: A reexamination. Archives of

General Psychiatry, 62, 247–253.

Rudd, M. D., Mandrusiak, M., & Joiner Jr, T. E. (2006). The case

Acknowledgement. This research was supported against no-suicide contracts: The commitment to treatment state-

by grant number 54010004 from ZonMw, The ment as a practice alternative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62,

243–251. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20227

Netherlands. Stoppe, G., Sandholzer, H., Huppertz, C., Duwe, H., & Staedt, J.

(1999). Family physicians and the risk of suicide in the depressed

Author contact: esther.meerwijk@ucsf.edu, with a copy to the elderly. Journal of Affective Disorders, 54, 193–198.

Editor: gpearson@uchc.edu Sun, F. K., Long, A., Boore, J., & Tsao, L. I. (2005). Suicide: A literature

review and its implications for nursing practice in Taiwan. Journal

of Psychiatry and Mental Health Nursing, 12, 447–455. doi: 10.1111/

j.1365-2850.2005.00863.x

References Talseth, A. G., Lindseth, A., Jacobsson, L., & Norberg, A. (1999). The

meaning of suicidal psychiatric in-patients’ experiences of being

American Psychiatric Association. (2003). Practice guideline for the cared for by mental health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29,

assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Arling- 1034–1041. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00990.x

ton, VA: Author. The AGREE Collaboration. (2001). Appraisal of Guidelines for Research

American Psychiatric Association. (2004). Practice guideline for the & Evaluation (AGREE) instrument. London: Author.

treatment of patients with schizophrenia (2nd ed.). Arlington, VA: Troister, T., Links, P. S., & Cutcliffe, J. (2008). Review of predictors of

Author. suicide within 1 year of discharge from a psychiatric hospital.

Beck, A., Kovacs, M., & Weissman, A. (1979). Assessment of suicidal Current Psychiatry Reports, 10, 60–65. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-

intention: The scale for suicide ideation. Journal of Consulting and 0011-8

Clinical Psychology, 47, 343–352. Williams, J. W., Jr., Noel, P. H., Cordes, J. A., Ramirez, G., & Pignone,

Cutcliffe, J. R., & Barker, P. (2004). The Nurses’ Global Assessment of M. (2002). Is this patient clinically depressed? Journal of the Ameri-

Suicide Risk (NGASR): Developing a tool for clinical practice. can Medical Association, 287, 1160–1170.

Perspectives in Psychiatric Care Vol. 46, No. 1, January 2010 73

Copyright of Perspectives in Psychiatric Care is the property of Blackwell Publishing Limited and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Hangnails and HomoeopathyDocument7 pagesHangnails and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomNo ratings yet

- Understanding-Ocd 2016 v2Document27 pagesUnderstanding-Ocd 2016 v2Samanjit Sen Gupta100% (1)

- Pathophysiology Community Aquired Pneumonia and AnemiaDocument3 pagesPathophysiology Community Aquired Pneumonia and Anemiapa3kmedina100% (2)

- Nursing Care Plan - Pericarditis PatientDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan - Pericarditis Patientsandie_best78% (9)

- Treatment of Cardiac Arrest in The Hyperbaric Environment - Key Steps On The Sequence of Care - Case ReportsDocument8 pagesTreatment of Cardiac Arrest in The Hyperbaric Environment - Key Steps On The Sequence of Care - Case Reportstonylee24No ratings yet

- Feline Asthma: Laura A. Nafe, DVM, MS, Dacvim (Saim)Document5 pagesFeline Asthma: Laura A. Nafe, DVM, MS, Dacvim (Saim)Miruna ChiriacNo ratings yet

- Ethic Ole Gal - FinalDocument79 pagesEthic Ole Gal - Finalpa3kmedinaNo ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- ApleDocument1 pageAplepa3kmedinaNo ratings yet

- NCP Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Presence of Secretion in Trachea-Bronchial Tree Secondary To History of CAPDocument2 pagesNCP Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Presence of Secretion in Trachea-Bronchial Tree Secondary To History of CAPpa3kmedina100% (1)

- Palliative Ward JuurnalDocument8 pagesPalliative Ward Juurnalpa3kmedinaNo ratings yet

- Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Presence of Secretion in Trachea-Bronchial Tree Secondary To History of CAPDocument2 pagesIneffective Airway Clearance Related To Presence of Secretion in Trachea-Bronchial Tree Secondary To History of CAPpa3kmedinaNo ratings yet

- NCP Proper Infection Related To Loss of Secondary DefenseDocument2 pagesNCP Proper Infection Related To Loss of Secondary Defensepa3kmedinaNo ratings yet

- NCP Background, Demographic Data, Dordon's Functional Health, Drug Study SAint Louis UniversityDocument21 pagesNCP Background, Demographic Data, Dordon's Functional Health, Drug Study SAint Louis Universitypa3kmedinaNo ratings yet

- 020 - Metabolism of Proteins 3Document12 pages020 - Metabolism of Proteins 3Sargonan RaviNo ratings yet

- Medication To Manage Abortion and MiscarriageDocument8 pagesMedication To Manage Abortion and MiscarriageNisaNo ratings yet

- List of Empanelled Hospitals in CGHS NagpurDocument58 pagesList of Empanelled Hospitals in CGHS NagpurRajatNo ratings yet

- Health and IllnessDocument2 pagesHealth and IllnessLize Decotelli HubnerNo ratings yet

- Remote Area Nursing Emergency GuidelinesDocument325 pagesRemote Area Nursing Emergency Guidelineslavinia_dobrescu_1No ratings yet

- Role of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma in Z-PlastyDocument3 pagesRole of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma in Z-PlastyasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- PWAT (Panographic Wound Assesment Tool) RevisedDocument4 pagesPWAT (Panographic Wound Assesment Tool) RevisedYunie ArmyatiNo ratings yet

- Buletin Farmasi 1/2014Document14 pagesBuletin Farmasi 1/2014afiq83100% (1)

- Chest XrayDocument6 pagesChest XrayAjit KumarNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in PregnancyDocument18 pagesHypertension in Pregnancyshubham kumarNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Management of Patients With Hearing and Balance DisordersDocument9 pagesAssessment and Management of Patients With Hearing and Balance Disordersxhemhae100% (1)

- NCM - 116 Lectute Prelim ModuleDocument7 pagesNCM - 116 Lectute Prelim ModuleHelen GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Transverse Dimension Diagnosis and Relevance to Functional OcclusionDocument6 pagesTransverse Dimension Diagnosis and Relevance to Functional OcclusionDino MainoNo ratings yet

- 2012 Karshaniya YavaguDocument4 pages2012 Karshaniya YavaguRANJEET SAWANTNo ratings yet

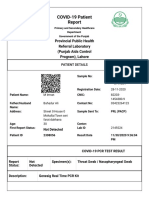

- COVID-19 Patient Report SummaryDocument2 pagesCOVID-19 Patient Report Summarymuhammad imranNo ratings yet

- Penatalaksanaan Penyakit Infeksi Tropik Dengan Ko-Infeksi Covid-19 - Assoc - Prof.dr - Dr. Kurnia Fitri Jamil, M.kes, SP - Pd-Kpti, FinasimDocument33 pagesPenatalaksanaan Penyakit Infeksi Tropik Dengan Ko-Infeksi Covid-19 - Assoc - Prof.dr - Dr. Kurnia Fitri Jamil, M.kes, SP - Pd-Kpti, FinasimFikri FachriNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Nursing Management and Interventions - NurseslabsDocument2 pagesAcute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Nursing Management and Interventions - NurseslabsSachin SinghNo ratings yet

- PATIENT INFORMATION - New App System - WebsiteDocument2 pagesPATIENT INFORMATION - New App System - WebsiteA M P KumarNo ratings yet

- Elevated BilirubinDocument5 pagesElevated BilirubinNovita ApramadhaNo ratings yet

- Amavatha & VathasonithaDocument125 pagesAmavatha & VathasonithaCicil AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Should Medical Marijuana Be Legalized For PatientsDocument4 pagesShould Medical Marijuana Be Legalized For PatientsBing Cossid Quinones CatzNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Type 2 DiabetesDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Type 2 Diabetesafmaadalrefplh100% (1)

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar PustakaNurfauziyahNo ratings yet

- Volume 43, Number 12, March 23, 2012Document56 pagesVolume 43, Number 12, March 23, 2012BladeNo ratings yet

- Windkessel EffectDocument11 pagesWindkessel EffectAkhmad HidayatNo ratings yet