Professional Documents

Culture Documents

27782293

Uploaded by

Peter HugeOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

27782293

Uploaded by

Peter HugeCopyright:

Available Formats

MUSIC

Another record shop

bucks the trend of

declining music stores

THE BUSINESS TIMES

FRIDAY, APRIL 26, 2013

PAGE 50

52

Evolving stage: Kuo Pao Kuns The Coffin Is Too

Big For The Hole (1985,far left) dealt with an

everyman character harried by bureaucratic

apathy and regulation. Today, Kuos works are

regarded as classics. In recent years, other political

works have surfaced which include (clockwise from

left) Jason Wees installation No More Tears Mr Lee

at Singapore Art Museum; Alfian Saat's Cooling Off

Day; veteran artist Tang Da Wus installation of

hammers called Same Same And No Difference

Between Unity And Self-destruction; and Eleanor

Wongs The Campaign to Confer the Public Service

star on JBJ. PHOTOS: SINGAPORE ART MUSEUM, VALENTINE WILLIE FINE

ART, FILE

N the Singapore Art Museum (SAM), there

is a portrait of Mr Lee Kuan Yew made entirely of shampoo bottle caps. The title of

the work is No More Tears Mr Lee. (No

More Tears is a brand of Johnson & Johnsons baby shampoo that doesnt sting the

eyes.)

Created by artist J`ason Wee, its a clever piece of political art. On the one hand, the elegant, monochromatic portrait presents a dignified image of Mr Lee. Its No More Tears title

harks back to the 1965 moment when he cried

on TV while announcing Singapores separation

from Malaysia. It suggests that decades after independence and the islands sterling economic

success, Mr Lee need cry no more.

Yet on the other hand, on a more

tongue-in-cheek level, the fact that the artwork is

made of 8,000 plastic bottle caps echoes the criticism thats often been levelled at Singapore: It is

safe, sterile and artificial kind of like shampoo.

Deeper thought on Wees work yields even more

provocative interpretations.

No More Tears Mr Lee is witty, layered and

oblique enough to be acquired and displayed by

SAM, which belongs to the National Heritage

Board. And Wee continues to have a successful

career as an artist.

But not all artists have been equally adept at

navigating the tricky terrain of what is permissible and what is not. And when theyre not, they

risk running afoul of the law.

Two weeks ago, some of the leading lights of

the arts community got together to present A

Manifesto For The Arts to the public. Those who

helped craft the manifesto include Nominated

Member of Parliament Janice Koh, theatre director Kok Heng Leun, arts manager Tay Tong, playwright Tan Tarn How and sociologist Terence

Chong among others.

Their six-point manifesto includes the statements: Art is fundamental; Art is about possibilities; Art unifies and divides; Art can be challenged but not censored; Art is political.

It is the final two points of the manifesto

Art is political and Art can be challenged but

not censored that got some of the folk who

crafted the manifesto hot under the collar.

One of them, T Sasitharan, the director of Intercultural Theatre Institute, says: Weve been

told by bureaucrats and politicians that art is not

supposed to be political, that you cannot indulge

in politics through your art, and that the two are

different.

But it is not true. Singapore is perhaps one

the few countries in the world where, if art is political, its a problem. Few other societies even

bat an eyelid if an artist makes a work that has a

political implication.

Art is political. Its about life, about who we

are. Art addresses and challenges the status quo,

at least by implication so it is political.

Those who created the manifesto over the

course of months are convinced that Singapore

society has reached a specific formative moment in the culture of Singapore where people

are looking deeper into who we are and asking

questions about our future, about the kind of life

well be living 20 or 30 years from now, says Mr

Sasitharan.

The group felt it important to release a manifesto explaining the meaning of art instead of

lurching from one incident to another because

there is no clear vision for the arts.

Again and again, the community has been

forced to confront the question; Can Singapore

artists ever be given the complete freedom to examine, document, question and critique life in

Singapore as they see it? The manifesto hopes to

emphasise that all art political or not should

be regarded as legitimate and acceptable forms

of human expression.

As theatre director Alvin Tan says with resignation: It gets so tiring for the arts community

to have to repeat the arguments again and

again.

When asked by Business Times, Benson

Puah, Chief Executive Officer of the National Arts

Council, says the council agrees with the manifestos broad principles: The Manifestos broad

principles resonate with NACs mission, which is

to make the arts an integral part of the lives of

the people of Singapore. To this end, we are committed to providing space for our artists to express themselves creatively and growing a discerning audience that supports diverse artistic

expression.

Whats accepted, whats not

Earlier this month, Samantha Lo, aka Sticker Lady, appeared in court on charges of mischief.

The street artist had pasted stickers above buttons of traffic lights bearing cheeky Singlish slogans such as Press until shiok and Anyhow

press police catch, among other acts.

Her arrest, however, provoked unhappiness

in the arts community who felt that Ms Los

works were a valuable art form because they

were humorous, relevant and captured a sentiment close to Singaporeans hearts.

Concerns were also aired when Ken Kweks

film Sex.Violence. Family Values was banned

Can Singapore accept

political art?

Political art seems more permissible when it is ambiguously or tastefully done,

but not when it is in-your-face, writes HELMI YUSOF

last year. In January, Elangovans Stoma which

tells the story of a Catholic priest defrocked over

sex abuse charges, was denied a performance licence because it contains sexually explicit, blasphemous and offensive references and language

which would be denigrating to the Catholic and

the wider Christian community, according to

the Media Development Authority.

And last year, the reading of political play

Square Moon by Wong Souk Yee, a former political detainee, was cancelled just days before the

event.

Her play was about a prisoner who escapes

from jail. In order to cover up the security lapse,

a fictional Homeland Security Department tries

to pass off one of their Marxist detainees as the

escaped prisoner.

The reasons for the cancellation of the reading remain unclear.

To be sure, though, several artworks have

been given the greenlight to deal with politics in

recent years from political plays such as Alfian

Saats Cooling-Off Day and Eleanor Wongs The

Campaign to Confer The Public Star on JBJ, to

the groundbreaking art exhibition titled Beyond

LKY that dealt directly with political themes.

Going back even further, Kuo Pao Kuns plays

in the 1980s such as The Coffin Is Too Big For

The Hole and No Parking On Odd Days dealt with

an everyman character harried by bureaucratic

apathy and regulations. Today, Kuos works are

canonised and revered around the region.

If one were to look closely at the works that

have been allowed to be staged or shown, three

patterns emerge:

Firstly, artworks that make political comments gently, sensitively, ambiguously and/or humorously are more likely to be given the greenlight than those that are more overt, crude, sensational and in-your-face.

Cooling-Off Day, for instance, showed real-life Singaporeans in all their various political

persuasions from the tudong-wearing makcik

who loves the Peoples Action Party, to a Chinese

ex-political detainee with bitter memories of her

arrest. Taken together, it formed an affectionate,

inoffensive patchwork of Singapores socio-political culture.

Secondly, artworks that are polemical and

Published and printed by Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Co. Regn. No. 198402868E.

The problem

with censoring

certain types

of works is

that it stops

society from

growing.

Society has to

evolve, and

works that are

supposedly

objectionable

should be

brought out

and discussed

instead of

being

censored.

Playwright Tan Tarn

How (above), whose

political play Fear of

Writing deals with

censorship

hard-hitting which have gotten the greenlight often present a broad range of viewpoints not

just one.

Chong Tze Chiens Charged was a savage and

racially-charged play filled with vulgarities. But

it was also a profound examination of racial ignorance that still exists among many Singaporeans. The play was staged twice to acclaim.

Thirdly, artists with a higher profile and longer track record of producing artistically significant work are more likely to be able to show provocative works compared to lesser-known artists.

Chew, Lo, Kwek and Lee are arguably less famous than the likes of Alfian, Wee and Chong

who have longer track records and whose works

routinely receive acclaim and attention.

Even then, higher-profile artists and arts companies still find the going tough sometimes.

Theatre company Wild Rice, for instance, was

allowed to stage political plays such as Wongs

The Campaign to Confer the Public Star on JBJ

in 2007. But it subsequently saw its government

funding cut first by $20,000 in 2010 and then by

$60,000 in 2011 because its works are deemed

incompatible with the core values promoted by

the Government and society or disparage the

Government, said the National Art Council

(NAC).

Earlier this month, however, NAC surprised

everyone when Wild Rice saw its funding return

to previous levels. It will receive $280,000 this

year, more than double the $110,000 it got last

year.

Not only that, local urban art collective

RSCLS, known for its edgy artwork in streetscapes, received $80,000. One of its members is

surprise, surprise the Sticker Lady.

Theatre director Tan concludes: Its so unpredictable.

Perhaps, that is why the Manifesto for the

Arts should have a place in the collective consciousness in understanding the arts in Singapore as it seeks a permanent recognition that art

may draw us together as much as it unveils

our differences and contradictions. And art

should allow for the process of conflict and contest of ideas. To date, the manifesto has almost

1,000 signatories online.

Is political art crucial?

Playwright Tan Tarn Hows 2011 play Fear of

Writing partly deals with censorship and its impact on the arts and creativity. He says: The

problem with censoring certain types of works

is that it stops society from growing.

Society has to evolve, and works that are

supposedly objectionable should be brought out

and discussed instead of being censored. Not

doing so damages or disadvantages not just the

artist, but also society.

Tan feels that all art good or bad, quiet or

provocative, ambiguous or in-your-face

should all have a place in the Singapore art

scene.

Art historian Louis Ho agrees with this view.

He adds: It is true that one can make art that

has no social or political value, art that is personal and subjective. But art that bites the bullet and engages itself in the broader social and

political sphere is far more interesting.

Ho, who pursued his art studies in New

York, says: We are a developed country and

we should learn to look at ourselves, criticise

ourselves and laugh at ourselves.

Indeed, many of the earliest signatories of

the manifesto feel that the judgment of good or

bad art, permissible or non-permissible art,

should not exist merely within the ambit of the

government. Many feel that these judgments

should be made by Singaporeans, who are mature and well-educated enough to decide what

they wish to consume or not.

Says sociologist Terence Chong: Perhaps,

the authorities shouldnt play the role of the art

critic. It should be up to the people to decide

what they want to watch.

Ultimately, the creators of the manifesto, as

well as the larger arts community, are searching for a way forward.

Mr Sasitharan concludes: Its not

far-fetched in todays context to meet a taxi driver whose daughter is studying film. Or a lorry

driver whose son is learning creative writing.

What are we to tell the young if we dont allow

for all kinds of art to flourish?

A member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Singapore. Customer Service (Circulation): 6388-3838, circs@sph.com.sg, Fax 6746-1925.

You might also like

- Conservation WorksheetDocument3 pagesConservation WorksheetPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- 27847835Document1 page27847835Peter HugeNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument16 pagesEnglishPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- 27919327Document1 page27919327Peter HugeNo ratings yet

- Think in EnglishDocument5 pagesThink in EnglishPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- Gritty Area To Get Glitzy Makeover: ThinkDocument1 pageGritty Area To Get Glitzy Makeover: ThinkPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- Photo of Demolition 4Document2 pagesPhoto of Demolition 4Peter HugeNo ratings yet

- I Am A Poor Man With No RoomDocument1 pageI Am A Poor Man With No RoomPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- Chem TuitionDocument1 pageChem TuitionPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- Photo of Demolition 1Document2 pagesPhoto of Demolition 1Peter HugeNo ratings yet

- I Am A Poor Man With No RoomDocument1 pageI Am A Poor Man With No RoomPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- CHP 1 Green Buildings Today Part 1Document27 pagesCHP 1 Green Buildings Today Part 1Peter HugeNo ratings yet

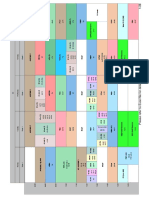

- 2011 JC1 TimeTable (Students) 17 Feb 1022 (W Venues)Document28 pages2011 JC1 TimeTable (Students) 17 Feb 1022 (W Venues)Peter HugeNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Expt 2A Acid Base Titration Worked SolutionDocument7 pages2015 - Expt 2A Acid Base Titration Worked SolutionPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- SatDocument24 pagesSatPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Expt 2A Acid Base TitrationDocument8 pages2015 - Expt 2A Acid Base TitrationPeter HugeNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Memo Re Intensification of Anti-Kidnapping Stratergy and Effort Against Motorcycle Riding Suspects (MRS)Document2 pagesMemo Re Intensification of Anti-Kidnapping Stratergy and Effort Against Motorcycle Riding Suspects (MRS)Wilben DanezNo ratings yet

- Ak. Jain Dukki Torts - PDF - Tort - DamagesDocument361 pagesAk. Jain Dukki Torts - PDF - Tort - Damagesdagarp08No ratings yet

- Document View PDFDocument4 pagesDocument View PDFCeberus233No ratings yet

- Model Consortium Agreement For APPROVALDocument34 pagesModel Consortium Agreement For APPROVALSoiab KhanNo ratings yet

- Full Download Technical Communication 12th Edition Markel Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Technical Communication 12th Edition Markel Test Bankchac49cjones100% (22)

- Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976)Document19 pagesRizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Aik Minute Ka MadrasaDocument137 pagesAik Minute Ka MadrasaDostNo ratings yet

- Canlas v. CADocument10 pagesCanlas v. CAPristine DropsNo ratings yet

- Revision Guide For AMD Athlon 64 and AMD Opteron Processors: Publication # Revision: Issue DateDocument85 pagesRevision Guide For AMD Athlon 64 and AMD Opteron Processors: Publication # Revision: Issue DateSajith Ranjeewa SenevirathneNo ratings yet

- People v. Aruta, G. R. 120915, April 3, 1998Document2 pagesPeople v. Aruta, G. R. 120915, April 3, 1998LeyardNo ratings yet

- Goldman Sachs Risk Management: November 17 2010 Presented By: Ken Forsyth Jeremy Poon Jamie MacdonaldDocument109 pagesGoldman Sachs Risk Management: November 17 2010 Presented By: Ken Forsyth Jeremy Poon Jamie MacdonaldPol BernardinoNo ratings yet

- Phase I - Price List (Towers JKLMNGH)Document1 pagePhase I - Price List (Towers JKLMNGH)Bharat ChatrathNo ratings yet

- Complete Accounting Cycle Practice Question PDFDocument2 pagesComplete Accounting Cycle Practice Question PDFshahwar.ansari04No ratings yet

- Problem NoDocument6 pagesProblem NoJayvee BalinoNo ratings yet

- Keeton AppealDocument3 pagesKeeton AppealJason SmathersNo ratings yet

- SSGC Bill JunDocument1 pageSSGC Bill Junshahzaib azamNo ratings yet

- Quiz - TheoryDocument4 pagesQuiz - TheoryClyde Tabligan100% (1)

- ASME B16-48 - Edtn - 2005Document50 pagesASME B16-48 - Edtn - 2005eceavcmNo ratings yet

- IA I Financial Accounting 3B MemoDocument5 pagesIA I Financial Accounting 3B MemoM CNo ratings yet

- Accounting STDDocument168 pagesAccounting STDChandra ShekharNo ratings yet

- Sapbpc NW 10.0 Dimension Data Load From Sap BW To Sap BPC v1Document84 pagesSapbpc NW 10.0 Dimension Data Load From Sap BW To Sap BPC v1lkmnmkl100% (1)

- Third Party Certification of ServingDocument4 pagesThird Party Certification of ServingBenNo ratings yet

- Duroosu L-Lugatuti L-Arabiyyah English KeyDocument61 pagesDuroosu L-Lugatuti L-Arabiyyah English KeyAsid MahmoodNo ratings yet

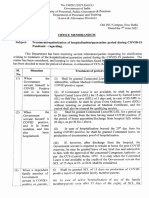

- DoPT Guidelines On Treatment - Regularization of Hospitalization - Quarantine Period During COVID 19 PandemicDocument2 pagesDoPT Guidelines On Treatment - Regularization of Hospitalization - Quarantine Period During COVID 19 PandemictapansNo ratings yet

- Deepali Project ReportDocument34 pagesDeepali Project ReportAshish MOHARENo ratings yet

- Sept. 2021 INSET Notice and Minutes of MeetingDocument8 pagesSept. 2021 INSET Notice and Minutes of MeetingSonny MatiasNo ratings yet

- Affinity (Medieval) : OriginsDocument4 pagesAffinity (Medieval) : OriginsNatia SaginashviliNo ratings yet

- A. Abstract: "Same-Sex Adoption Rights"Document12 pagesA. Abstract: "Same-Sex Adoption Rights"api-310703244No ratings yet

- Fault (Culpa) : Accountability (121-123)Document4 pagesFault (Culpa) : Accountability (121-123)kevior2No ratings yet

- Ntf-Elcac Joint Memorandum CIRCULAR NO. 01, S. 2019Document24 pagesNtf-Elcac Joint Memorandum CIRCULAR NO. 01, S. 2019Jereille Gayaso100% (1)