Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hypocalcaemia and Hypomagnesaemia

Uploaded by

Kadiwala Dairy FarmOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hypocalcaemia and Hypomagnesaemia

Uploaded by

Kadiwala Dairy FarmCopyright:

Available Formats

Hypocalcaemia and Hypomagnesaemia

Milk Fever (Hypocalcaemia, Parturient Paresis)

The average annual incidence of milk fever in UK

dairy herds is estimated to be approximately 7-8 per

cent but individual farms may have a much higher

prevalence when calving at pasture. Milk fever is

more common in older dairy cows but can also

affect older beef cows (fourth calvers or older)

especially dairy crosses (e.g Limousin x Holstein),

again more common in autumn calving cows.

Fig 2: Muscle weakness in a recently calved beef cow

with early hypocalcaemia

Fig 1: Milk fever, although more common in dairy

breeds, can also affect older beef cows (fourth

calvers or older) especially dairy crosses (e.g

Limousin x Holstein), again more common in autumn

calving cows (note the ripening spring barley in the

background).

Cause

Blood calcium concentration is maintained in a fine

balance via various hormonal pathways, noteably of

parathyroid origin. A cow yielding 40 litres of milk

daily suddenly requires an extra dietary intake of

80g calcium per day but these processes take 2-3

days to become fully active and if they fail,

hypocalcaemia results. Older cows respond more

slowly, and are thus more prone to milk fever. Low

magnesium status may also interfere with calcium

control.

Clinical presentation

Clinical signs usually occur within 24 hours after

parturition but can occur at or before calving, and in

exceptional situations (often very high yielding cow

during oestrus) several weeks/months after calving.

The clinical signs progress over a period of 12 to 24

hours. There is teeth grinding and muscle tremors,

stiff legs, straight hocks and "paddling" of the feet

when standing during the early stages.

Copyright NADIS 2016

The clinical signs progress to muscle weakness and

the cow lies down with a characteristic kink

("S-bend") in her neck, later the head is held

against the chest. Gut stasis causes bloat and

constipation. Left untreated, the cow becomes

comatose and lies on her side. Ruminal bloat and/or

paralysis of respiratory muscles cause death in

untreated cattle after 12-24 hours.

Fig 3: The clinical signs progress to muscle

weakness and the cow lies down with the head held

against the chest.

valve with the bottle held 30-40 cm above the

infusion site. Some veterinary surgeons also

administer solutions containing magnesium and/or

phosphorous. Towards the end of intravenous

infusion, the cow will typically eructate several times

and pass firm faeces, and urinate on standing. The

cow should be propped on her brisket and will

frequently make attempts to stand 5-10 minutes

later. There is no advantage gained by forcing the

cow to stand prematurely.

Fig 4: Left untreated, the cow becomes comatose and

lies on her side. Ruminal bloat and/or paralysis of

respiratory muscles cause death in untreated cattle

after 12-24 hours.

Potential complications of hypocalcaemia include

uterine inertia (leading to calving problems and/or

stillbirth), prolapse of the uterus, inhalation of rumen

contents when cast causing pneumonia, and

pressure damage to nerves and muscles.

Fig 6: Administer 400ml of 40% calcium

borogluconate solution warmed to body temperature

by slow intravenous injection (over 5-10 minutes) into

the jugular vein.

Fig 5: Potential complications of hypocalcaemia

include uterine inertia leading to calving problems.

Differential diagnosis

Acute toxic mastitis

Physical injury/nerve paralysis

Uterine rupture

Haemorrhage caused by dystocia

Acidosis/grain overload

Botulism

Hypophosphataemia

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based upon the cow's history,

clinical signs, and response to intravenous calcium

borogluconate solution within minutes. Clinical signs

occur when serum calcium levels fall below

1.5mmol/l (normal 2.2-2.6 mmol/l) and are often as

low as 0.4 mmol/l in cattle with advanced disease.

Treatment

After careful clinical examination, administer 400ml

of 40% calcium borogluconate solution (containing

12g calcium) warmed to body temperature, by slow

intravenous injection (over 5-10 minutes) into the

jugular vein using a 14 gauge needle and flutter

Copyright NADIS 2016

Fig 7: Use a 14 gauge needle and flutter valve with

the bottle held 30-40 cm above the infusion site.

Some veterinary surgeons also administer 400ml of

40% calcium borogluconate subcutaneously in an

attempt to prevent recurrence which can occur in

approximately 25% of cases. The cow should not

be milked for 24 hours and the calf removed after

feeding colostrum.

Prevention/control measures

Cows should be in condition 2.5-3 at calving. The

primary cause of a milk fever problem is usually the

high potassium or calcium content of the forage

content in the dry period. Thus changing the forage

fed to the dry cows may reduce herd problems. Low

dietary magnesium may be a factor and provision of

magnesium chloride will also lower the dietary

cation-anion balance (DCAB) of the diet.

Manipulation of the dry cow diet is the most-cost

effective method of controlling the incidence of

hypocalcaemia. Manipulation of the DCAB should

be considered in discussion with the farmer's

veterinary surgeon and/or nutritional advisor.

Limit the amount of calcium in the dry cow diet in

the 3-4 weeks prior to calving to less than 50g per

head per day (ideally less than 30g per day).

Magnesium levels in the diet should be above 40g

per day. This proves very difficult to achieve in

grass-based forage systems.

Cows known to be at risk of milk fever can be given

calcium at/just before calving using drenches (150g

calcium chloride daily), gels and boluses.

Hypomagnesaemia (Grass Staggers, Grass

Tetany)

The average annual incidence of acute

hypomagnesaemia in the UK is under 1 per cent.

Most cases occur in recently-calved beef cows but

disease can also occur in dairy cows particularly if

unsupplemented during the dry period. There is a

range of clinical signs from sub-clinical disease to

sudden death. Acute hypomagnesaemia is one of

the few true veterinary emergencies.

fibre and increase the rate of passage of food

material through the rumen reducing time for the

absorption.

Fig 9: Lush pastures are low in fibre and increase the

rate of passage of food material through the rumen

reducing time for the absorption.

Clinical presentation

Sudden death without premonitory signs is

encountered most commonly in older lactating beef

cows 4-8 weeks after calving maintained at pasture

without appropriate supplementary feeding. The

cow is found dead with disturbed soil around its feet

indicating paddling/seizure activity often after

stormy weather.

In acute disease there is initial excitability with high

head carriage, twitching of muscles (especially

around the head) and incoordination ("staggering

gait"). Affected cows become separated from the

group and have a startled expression, show an

exaggerated blink reflex and frequent grinding of

the teeth There is rapid progression to periods of

seizure activity. During seizure activity there is

frenzied paddling of the limbs, sudden eye

movements, rapid pounding heart, and teeth

grinding with frothy salivation.

Fig 8: Sudden death due to hypomagnesaemia.

Aetiology

Despite its vital importance, there are no specific

control mechanisms for magnesium levels. The

amount and concentration of magnesium in the

body is dependent upon absorption mainly from the

rumen which varies from 10-35%, the requirement

for milk production - and excretion by the kidneys.

Factors influencing the availability of dietary

magnesium include magnesium levels in the soil

and grass which vary considerably. High levels of

potassium (application of potash fertilisers) disrupt

the absorption of magnesium. High levels of

ammonia (from nitrogenous fertilisers) inhibit

magnesium absorption. Lush pastures are low in

Copyright NADIS 2016

Fig 10: Affected cows become separated from the

group and have a startled expression with frequent

teeth grinding, an exaggerated blink reflex and frothy

salivation.

Fig 11: During seizure activity there is frenzied

paddling of the limbs, sudden eye movements, and a

rapid pounding heart.

Death may follow at any stage. Relapses are

common even after apparent correct treatment. The

majority of cows in the group may be affected

subclinically.

Subclinical/chronic

disease

often

goes

unrecognised but investigations have revealed an

annual rate of 3-4 per cent in lactating dairy cows.

Cows may appear slightly nervous, are reluctant to

be milked or herded, and have depressed dry

matter intake and poor milk yield. Dairy cows with

subclinical hypomagnesaemia in the dry period are

predisposed to hypocalcaemia.

Milk tetany is very occasionally reported in 4-8

week-old beef calves. Affected calves show sudden

onset seizure activity which should be differentiated

from lead poisoning.

Differential diagnoses in adult cows

Sudden death:

Lightning strike/electrocution

Anthrax

Clostridial disease such as blackleg

Acute disease:

Lead poisoning

Hypocalcaemia

Nervous acetonaemia (dairy cow)

Diagnosis

Plasma magnesium less than 0.8mmol/l indicate

subclinical hypomagnesaemia and an increased

risk of developing acute hypomagnesaemia.

Treatment

It is essential to call a veterinary surgeon to

administer a sedative drug to control the cow's

seizure activity and prevent a fatal convulsion, and

to facilitate intravenous treatment.

Fig 12: Your veterinary surgeon will likely administer

a sedative drug to control the cow's seizure activity

and prevent a fatal convulsion which also facilitates

intravenous treatment.

Your veterinary surgeon will likely administer 400ml

of 40% calcium borogluconate plus 50 mls of 25%

magnesium sulphate by slow intravenous injection

once seizure activity has been controlled. The

remainder of the 400ml bottle of 25% magnesium

sulphate is given by subcutaneous injection. The

cow should then be raised into sternal recumbency

and left quietly. The administration of magnesium

sulphate by injection will only increase plasma

levels for 6 to 12 hours, therefore it is essential to

offer concentrates/hay to ensure adequate dietary

intake to prevent relapse.

The remaining cows are very likely to have

subclinical hypomagnesaemia, and will be at risk

from acute grass staggers. Blood sampling of a

group of at least five cows could be performed to

check the herd magnesium status but it would be

prudent to implement preventive measures

immediately.

Prevention/control measures

The total diet should contain 2.5g/kg DM of

magnesium to meet requirements of the majority of

lactating cows at pasture. The best method is to use

60g magnesium oxide (calcined magnesite) per cow

per day in high-magnesium cobs. Magnesium salts

are relatively inexpensive and the cost of

supplementation 100 cows for two months will be

less than the loss on one animal due to

hypomagnesaemia

Fig 13: The best method is to use 60g magnesium

oxide (calcined magnesite) per cow per day in

high-magnesium cobs.

Copyright NADIS 2016

The sole water supply can be medicated with

soluble magnesium salts such as chloride, sulphate

or acetate. Pastures may be dusted during high-risk

periods with finely ground calcined magnesite every

10-14 days. Intra-ruminal boluses give a slow

release of relatively small amounts of magnesium

into the rumen over a period of four weeks.

Magnesium salts and minerals are unpalatable

therefore ad-lib minerals are not satisfactory.

Supplementation is especially important during

stormy weather when roughage, such as straw, can

be beneficial for beef cows.

Fig 15: Supplementation is especially important

during stormy weather when roughage, such as

straw, can be beneficial for beef cows.

Fig 14: Supplementing autumn-calving beef cows in

early October.

NADIS seeks to ensure that the information contained within this document is accurate at the time of

printing. However, subject to the operation of law NADIS accepts no liability for loss, damage or injury

howsoever caused or suffered directly or indirectly in relation to information and opinions contained in or

omitted from this document.

To see the full range of NADIS livestock health bulletins please visit www.nadis.org.uk

Copyright NADIS 2016

You might also like

- Advantages of Using Fishmeal in Animal FeedsDocument3 pagesAdvantages of Using Fishmeal in Animal FeedsHjktdmhmNo ratings yet

- Bypass Protein Technology SL No 4 An Group 0Document4 pagesBypass Protein Technology SL No 4 An Group 0Kadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Estatto KrollDocument2 pagesEstatto KrollKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Cow Supplier and Cow Farmerand CosultantDocument2 pagesCow Supplier and Cow Farmerand CosultantKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Advanced Technologies Allow "Small Dairy Farms" in Israel To Be CompetitiveDocument7 pagesAdvanced Technologies Allow "Small Dairy Farms" in Israel To Be CompetitiveKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Cow Managment in Hot ClimateDocument1 pageCow Managment in Hot ClimateKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Fish Meal Role in Cattle FeedDocument2 pagesFish Meal Role in Cattle FeedKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Bypass Fat in Dairy Ration-A ReviewDocument17 pagesBypass Fat in Dairy Ration-A ReviewKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument3 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Using Fishmeal in Animal FeedsDocument3 pagesAdvantages of Using Fishmeal in Animal FeedsHjktdmhmNo ratings yet

- Aadhunik Pashu Palan PDFDocument214 pagesAadhunik Pashu Palan PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Magazine - Pashudhan Prakash 2014 PDFDocument124 pagesMagazine - Pashudhan Prakash 2014 PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- An HusbandryDocument74 pagesAn HusbandryManoj SolathNo ratings yet

- Latest Guidelines For Organisation of Camps PDFDocument16 pagesLatest Guidelines For Organisation of Camps PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Pashudhan Parkash 2015 PDFDocument123 pagesPashudhan Parkash 2015 PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Aadhunik Pashu Palan PDFDocument214 pagesAadhunik Pashu Palan PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Intro To Meat Goat NutritionDocument29 pagesIntro To Meat Goat NutritionKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- PashudhanPrakash Pdffile PDFDocument72 pagesPashudhanPrakash Pdffile PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- AÜ'm' AÜ'm' AÜ'm' AÜ'm' - 1 1 1 1Document26 pagesAÜ'm' AÜ'm' AÜ'm' AÜ'm' - 1 1 1 1Kadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Adarsh Pash Up AlanDocument34 pagesAdarsh Pash Up AlanKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Pash Us Am WardhanDocument31 pagesPash Us Am WardhanKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- PashuDhan Prakash - Edition-4 PDFDocument100 pagesPashuDhan Prakash - Edition-4 PDFKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Dairy and SDGsDocument1 pageDairy and SDGsKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Golden Rule EnglishDocument16 pagesGolden Rule EnglishKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Silage Making For Dairy FarmersDocument5 pagesSilage Making For Dairy FarmersAhmed Saad QureshiNo ratings yet

- Mineral DeficienciesDocument1 pageMineral DeficienciesKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Whea or Rice Straw TreatmentDocument2 pagesWhea or Rice Straw TreatmentIbrahim KhanNo ratings yet

- TMR Feed Formulator For DistributionDocument844 pagesTMR Feed Formulator For DistributionKadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- NDDB DMPDocument124 pagesNDDB DMPelanthamizhmaran100% (1)

- Dairy Samachar April June2014Document8 pagesDairy Samachar April June2014Kadiwala Dairy FarmNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Anxiety Disorders - Causes, Types, Symptoms, & TreatmentsDocument5 pagesAnxiety Disorders - Causes, Types, Symptoms, & Treatmentsrehaan662No ratings yet

- LG250CDocument2 pagesLG250CCarlosNo ratings yet

- IV. Network Modeling, Simple SystemDocument16 pagesIV. Network Modeling, Simple SystemJaya BayuNo ratings yet

- Manual Wire Rope Winches Wall-Mounted Wire Rope Winch SW-W: Equipment and ProcessingDocument1 pageManual Wire Rope Winches Wall-Mounted Wire Rope Winch SW-W: Equipment and Processingdrg gocNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus: Course Code Course Title ECTS CreditsDocument3 pagesCourse Syllabus: Course Code Course Title ECTS CreditsHanaa HamadallahNo ratings yet

- Innerwear Industry Pitch PresentationDocument19 pagesInnerwear Industry Pitch PresentationRupeshKumarNo ratings yet

- SAT Practice TestDocument77 pagesSAT Practice TestfhfsfplNo ratings yet

- Sat Vocabulary Lesson and Practice Lesson 5Document3 pagesSat Vocabulary Lesson and Practice Lesson 5api-430952728No ratings yet

- Pediatric EmergenciesDocument47 pagesPediatric EmergenciesahmedNo ratings yet

- Faa Registry: N-Number Inquiry ResultsDocument3 pagesFaa Registry: N-Number Inquiry Resultsolga duqueNo ratings yet

- Electric ScootorDocument40 pagesElectric Scootor01fe19bme079No ratings yet

- DudjDocument4 pagesDudjsyaiful rinantoNo ratings yet

- Worlds Apart: A Story of Three Possible Warmer WorldsDocument1 pageWorlds Apart: A Story of Three Possible Warmer WorldsJuan Jose SossaNo ratings yet

- FYP ProposalDocument11 pagesFYP ProposalArslan SamNo ratings yet

- SPL Lab Report3Document49 pagesSPL Lab Report3nadif hasan purnoNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Aesculap PDFDocument16 pagesCatalogo Aesculap PDFHansNo ratings yet

- Immigrant Italian Stone CarversDocument56 pagesImmigrant Italian Stone Carversglis7100% (2)

- Port Name: Port of BaltimoreDocument17 pagesPort Name: Port of Baltimoremohd1khairul1anuarNo ratings yet

- Stalthon Rib and InfillDocument2 pagesStalthon Rib and InfillAndrea GibsonNo ratings yet

- The Light Fantastic by Sarah CombsDocument34 pagesThe Light Fantastic by Sarah CombsCandlewick PressNo ratings yet

- FemDocument4 pagesFemAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- PEH Q3 Long QuizDocument1 pagePEH Q3 Long QuizBenedict LumagueNo ratings yet

- tGr12OM CheResoBookU78910Document110 pagestGr12OM CheResoBookU78910Jamunanantha PranavanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Chapter 9 ErosiondepositionDocument1 pageLesson 1 Chapter 9 Erosiondepositionapi-249320969No ratings yet

- Hydrodynamic Calculation Butterfly Valve (Double Disc)Document31 pagesHydrodynamic Calculation Butterfly Valve (Double Disc)met-calcNo ratings yet

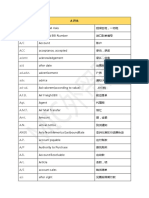

- 外贸专业术语Document13 pages外贸专业术语邱建华No ratings yet

- C.Abdul Hakeem College of Engineering and Technology, Melvisharam Department of Aeronautical Engineering Academic Year 2020-2021 (ODD)Document1 pageC.Abdul Hakeem College of Engineering and Technology, Melvisharam Department of Aeronautical Engineering Academic Year 2020-2021 (ODD)shabeerNo ratings yet

- World's Standard Model G6A!: Low Signal RelayDocument9 pagesWorld's Standard Model G6A!: Low Signal RelayEgiNo ratings yet

- SCM (Subway Project Report)Document13 pagesSCM (Subway Project Report)Beast aNo ratings yet

- SP Essay 1Document14 pagesSP Essay 1api-511870420No ratings yet