Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Authority at Work Internal Models and Their Organizational Consequences

Uploaded by

BangSUSingaporeLiangCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Authority at Work Internal Models and Their Organizational Consequences

Uploaded by

BangSUSingaporeLiangCopyright:

Available Formats

* Academy of Management Review

1994. Vol. 19, No. 1, 17-50.

AUTHORITY AT WORK: INTERNAL MODELS AND

THEIR ORGANIZATIONAL CONSEQUENCES

WILLIAM A. KAHN

KATHY E. KRAM

Boston University

This article focuses on how organization members authorize and deauthorize both others and themselves in the course of doing their

work. We argue that these authorizing processes are shaped, in part,

by enduring, often unacknowledged stances toward authority itself.

In tum, we suggest that these stances are enacted in similar ways

across hierarchical and collaborative work arrangements and across

various roles and positions. These stances areas Hirschhom (1990)

suggestedinternalized models. Working from a theoretical framework that combines concepts from developmental and clinical psychology, group dynamics, and organizational behavior, we define

and illustrate three types of internal models of authority: dependence,

counterdependence, and interdependence. We offer propositions

about how these internal models influence organization members'

behaviors during task performances generally, and more specifically,

as members of hierarchical dyads and work teams. We also suggest

propositions about how these internal models of authority are triggered and change in the context of organizational life. Finally, we

offer research methods and strategies by which to empirically examine these propositions.

Quite a lot is known about the nature and use of authority in traditional hierarchical organizations. Authority is defined as the given right

to perform roles; such rights are legitimated by consensual decisions

codified in constitutions, contracts, charters, rulings, and other accepted

institutional sanctions (Cartwright, 1965; Gilman, 1962; Katz & Kahn,

1987). Work organizations depend on members occupying roles of authority to ensure the predictable performance of organizational tasks (Simon,

1947). It is when organization members occupy their work roles (i.e., identify themselves with the authority mandated to those roles) that they have

the legitimate power to pursue their rights, duties, and obligations in the

service of their tasks. Authority offers a legitimate base to have power

and from which to influence others and bring about the completion of

work tasks. It is legitimate power vested in particular people or positions

for system purposes (Weber, 1947).

This definition of authority is particularly well suited to traditional

hierarchical organizations that operate according to powers vested in

specific offices and, therefore, officeholders. Organization members' tra17

18

Academy of Management Review

January

ditionally legitimate rights to wield power derive from occupying offices

that have affixed to them particular rules of influence, which specify the

officeholders by whom they are influenced and those over whom they

wield influence (Barnard, 1938; Simon, 1947; Weber, 1947). These rules are

woven into the fabric of the traditional hierarchical bureaucracy, giving

order and predictability to transactions among officeholders. It is increasingly the case, however, that traditional hierarchical bureaucratic organizations are changing, and with them are changing the ways in which

authority and power are distributed among their members. Handy (1989:

130) wrote convincingly that "the changing complexity, variety, and

spread of reaction which is now a feature of so many organizations"

makes it increasingly difficult to specify and reify in advance exactly who

should be doing what, when, in what order, and with whom for successful

task performance. Thus, organization members must negotiate such parameters themselves. Hirschhorn (1988, 1990) pushed this idea further,

noting that the pace, depth, and accumulation of change in the postindustrial organizational setting requires the maximum use of human resources. Such use, in turn, results in collaboration between leaders and

subordinates whereby duty and authority are negotiated: "The leader no

longer charts the organization's work, with subordinates lined up to do

the bidding. Instead, the leader and the subordinates must collaborate"

(Hirschhorn, 1990: 529). Such collaboration is at the core of what Lawler

(1988) describes as high involvement systems.

Such collaboration is based on negotiated authority, whereby leader

and subordinates jointly decide the scope of the power each has over their

tasks (Handy, 1989). Such decisions authorize leaders and subordinates to

be responsible for certain aspects of task performance. Authorizing is the

giving of authority, that is, the right to do work. Organization members

are authorized not simply when they are assigned responsibility for tasks

(i.e., delegated authority) but also when they are supported by others who

are either formally or informally connected to those roles. Organization

members are de-authorized when such support is withheld (even when

their rights have been formally delegated). In traditional bureaucratic

organizations, officeholders become authorized by the power of the offices they occupy. In more collaborative work arrangements, organization

members become authorized less through their identification with particular offices and more through their negotiations with other members

about task performances. As these newer organization forms become

more prevalent and necessary, it becomes increasingly appropriate to

conceptualize authority in terms of its underlying process dimensions:

the ways that organization members authorize and de-authorize both others and themselves in the course of doing their work.

Although authorizing and de-authorizing processes have not been

examined directly, it is clear that they occur in ongoing co-worker relations. Implicit in existing literatures on traditional authority is the following premise: How organization members actually work from roles of au-

1994

Kahn and Kiam

19

thority to accomplish tasks is not simply a matter of legitimation and

mandate, it is also a result of actual interactions between leaders and

followers (Gabarro & Kotter, 1980). It is within such interactions that the

scope and limits of the authority of both leaders and followers are negotiated (Bendix, 1974). Both leaders and followers are separately interpreting the nature of the leader's authority (i.e., given rights, duties, obligations, privileges, and powers), which cannot translate into power and

influence unless it is acknowledged by followers as valid (Gouldner, 1954;

Simon, 1947). Interactions between leaders and followers become joint

interpretations of authority, because each one can increase or decrease

the other's authority by offering or withholding legitimating support

(Bass, 1990) irrespective of formal delegation of task responsibility. This

interpretive process is often unconscious, as Barnard (1938) pointed out in

defining the zone of indifference to describe how followers automatically

defined their leaders' orders as acceptable unless the illegitimate nature

of those orders (on various dimensions) triggered their conscious questioning. What is actually triggered is the conscious process of authorizing

and de-authorizing oneself and others to engage in work.

Authority Relations

Researchers know little else directly about authorizing and deauthorizing processes in work organizations. However, there is a long

tradition of research and theory on authority relations (which generally

does not include the new collaborative organization forms), which points

to two fundamental types of influencessifuafionaJ and individualon

how organization members define and create their authority relations.

Each of these influences shapes the dynamics of authority and power

(Bass, 1990; House, 1988). The situational factors generally focus on how

organization members are externally driven to conform with existing

norms of thought and action, with a primary focus on "followership." The

literature on individual factors generally relates to how individuals are

internally driven toward power in certain ways, with a primary focus on

leadership. Each influence offers clues to key components of authorizing

and de-authorizing processes.

Situational factors. Research in the domain of situational factors has

been focused on how the social structure of situations presses individuals

to create and obey rules of hierarchical authority. Perhaps the most wellknown research is Milgram's (1974) set of experiments showing the conditions under which subjects obeyed authority figures to the extent that

they acted inhumanely toward others while disavowing responsibility for

their actions. In the initial experiment, 65 percent of the subjects followed

the authority figure's instructions to continue punishing the "learner"

(i.e., confederate) until they had reached the maximum shock intensity of

450 volts. Milgram noted that the key variable was the sense of diminished responsibility that subjects felt: They felt that they were agents (of

the authority figure) rather than actors responsible for their behaviors.

20

Academy oi Management Review

January

Variations on the basic experiment showed that manipulations that increased the psychological distance between "teacher" and "learner" decreased subjects' perceptions of personal responsibility, which increased

their obedience to authority. Milgram's experiments indicated the power

that social situations have to dictate how members enacted their roles as

both subordinates (to legitimate authority) and authority figures (to

"learners"). They showed how even temporary social systems exert pressures on people to act as if they have no choice but to create and reinforce

particular types of authority relations.

Another classic social psychological experiment attests to the power

of situations to determine how people create and respond within authority

relations through the roles they assume. Zimbardo's (Haney, Banks, &

Zimbardo, 1973) experiment involved the creation of a temporary system,

a prison, and the randomly assigned casting of individuals into system

roles, "prisoner" or "guard." In little time the prisoners accepted themselves as inferior and acted passively, whereas the guards accepted

themselves as superior and engaged in episodes of abusive, authoritarian behavior. The subjects thus projected themselves emotionally and

cognitively into the roles into which they were physically placed, on the

basis of their stereotypic understandings of the norms by which prisoners

and guards act and prison systems operate. On the basis of accepting

those norms, Zimbardo's subjects created and enacted stereotypic relations of authority between the powerful and the powerless. The experimenters halted the experiment six days into a planned two-week simulation because of the emotional force with which the subjects took up their

roles as superior and subordinate. The experiment's duration was enough

to show how powerfully the roles that individuals occupyeven in temporary social systemsshape the relations of authority they create and

enact. It also showed how drawn people are to adopt norms to help them

define their situations and themselves, regulate their behaviors, locate

themselves hierarchically, and create authority relations.

These classic studies indicate the power of roles and norms to shape

people's experiences and behaviors in authority relations. Organizations

rely on people occupying given roles to reduce the variability, instability,

and unpredictability accompanying human behavior and to withstand

personnel turnover (Katz & Kahn, 1987). Also, they traditionally have relied on predictable authority relationships between superior and subordinate that follow accepted norms of relative power and powerlessness,

respectively (Simon, 1947). Although these authority relations typically

are neither so brutally polarized as those evidenced in Zimbardo's experiment nor so explicitly fraught with anxiety and pain as those evidenced

in Milgram's work, they are nevertheless subject to similar social, role,

and normative pressures (and may lead to equally brutal results; cf.

Arendt's [1965] banality of evil). The more contemporary variable of organizational culture (Schein, 1985) maintains the focus on the complexity of

1994

Kahn and Kiam

21

the situational influences that create and maintain particular types of

authority relations.

The implication here is that when individuals enter into both temporary and ongoing systems, there are cues that help them take up certain

types of roles (e.g., "teacher," "prisoner"), follow certain behavioral

norms, and create certain types of authority relations. These cues lead to

the authorizing of formal leaders occupying certain offices, regardless of

the individuals occupying particular superior and subordinate positions.

What is left unexplained, however, is why some individuals in such situations do not create expected authority relations; that is, why 35 percent

of Milgram's (1974) subjects did not show complete obedience to the authority figure but acted counternormatively. There are individual-level

differences thatin conjunction with situational influenceshelp explain how individuals occupy superior and subordinate roles.

Individual factors. A variety of individual factors help account for

how organization members frame and perform superior and subordinate

roles. In terms of enduring personality variables, two concepts illuminate

the relation between personality and power. One concept is the authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950),

measured by the F-scale, which is associated with power-seeking and

personality attributes that include conservatism, emotional coldness,

hostility toward minority groups, and resistance to change (Bass, 1990)

attributes indicating rigidity. Researchers have explored the relations

between individuals' F-scores and the types of leaders they prefer (high

F-scores prefer autocratic leaders and low F-scores prefer consultative

leaders), and the effects that authority-relation matches and mismatches

have on both leaders and followers (see Bass, 1990). A second concept is

Machiavellianism (Christie & Geis, 1970), which refers to the extent to

which people are impervious to and resist social influences and emotional or moral considerations (high Machs), or are susceptible to such

influences and are distracted by interpersonal concerns (low Machs). Researchers have noted the generally consistent relation between expressed Machiavellian attitudes and behaviors (Epstein, 1969). According

to these concepts, individuals have particular motives or needs to establish specific types of authority relations in which they feel comfortable.

The implication of these traditional concepts, for our purposes here,

is that people are drawn to create or enact authority relations partly on

the basis of compelling, deep-seated personality attributes of which they

may be only partly aware (McClelland, 1985). Recent research similarly

suggests a connection between individual differences and constructed

relationships. Researchers have noted how various self-concepts shape

organization members' abilities to perform effectively. Concepts that

have received attention in this regard include self-efficacy (Bandura,

1982), self-confidence (Mowday, 1978), self-understanding (McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison, 1988), and self-actualization (Burns, 1978). The tenor of

22

Academy of Management Review

January

the research is that members who are high on such self-concept dimensions are better able to create and push toward goals, and they display

(and gain) leadership characteristics (Bennis & Nanus, 1985). A related

research stream has focused on the personal characters of leaders and

executives, in whom certain tendencies toward defensiveness (Argyris,

1982, 1990) or personal achievement (Kaplan, 1991) lead toward the creation of particular (and variously effective) authority relations. There also

is a more unconscious, psychopathological relation between character

and leadership style, as was noted by Kets de Vries and Miller (1987).

They describe how neurotic styles of leaders, based on unconscious fantasies, create shared pathologies in their systems mirroring those fantasies (e.g., persecution, helplessness, narcissism, compulsiveness, schizoid detachment). The vehicles by which these neurotic styles are enacted

and shared are the authority relations established by leaders and members as they interact.

The individual factors described here help explain how organization

members engage in particular types of leadership behaviors, based on

personality attributes and self-concepts, that offset some of the situational influences reviewed above. The literature reviewed here suggests

that individuals are internally motivated to repeatedly develop certain

types of authority relations that enable them to use or react to power in

ways that are comfortable or necessary for them, for whatever conscious

or unconscious reasons. The authority relations that individuals create

are thus the vehicles through which they satisfy their needs or express

their attributes.

Implications. This brief review of the traditional literatures on authority relations suggests particular gaps in knowledge. First, it seems

that the theory and research about situational influences on authority

relations is more developed than that about individual-level influences;

for example, researchers have not yet conceptualized an individual difference variable that would speak directly to what drives people to authorize and de-authorize themselves and others in patterned ways. Second, it is clear that researchers have, as noted above, generally linked

followership (i.e., obedience) to situational influences and leadership to

individual difference influences, and they have kept the two domains

separate (for an important exception, see Burns, 1978). It is likely, however, that followership and leadership are more tightly linked within individuals; that is, people have particular stances toward authority relations that affect their actions as hierarchical superiors and subordinates

alike, and in the more collaborative work arrangement, as co-workers

(Hirschhom, 1990). This article begins to fill these gaps in knowledge by

building on two implications from the literature reviewed above.

First, the situational literature implies that authorizing is related to

the allowing of personal thoughts, feelings, and beliefsone's own and

othersto be brought into the performance of work roles. There is a

continuum here, in terms of the extent to which such personal dimensions

1994

Kahn and Kiam

23

are imported into role performances. When the 35 percent minority of

Milgram's subjects authorized themselves to be responsible for their actions as subordinates, they did so by taking seriously their personal beliefs and feelings and using them as the standards by which they acted.

Most of Milgram's subjects, like those of Zimbardo, did just the opposite,

keeping their personal sensibilities out of the rolessuperior or subordinateinto which they were cast. In both situations, there were external

cues suggesting that subjects split off their personal feelings, beliefs, and

thoughts and leave them outside the confines of given hierarchical roles.

It is likely that subjects' responses were related to some sort of individuallevel factor that led some to follow internal cues directing them to access

rather than split off personal dimensions and take rather than deny personal responsibility. Authorizing, then, is defined not simply in terms of

giving the right to do work; it is also giving the right to bring the personal self (one's own or another's) into the work role (see Gould, 1993;

Hirschhorn, 1985, 1990; Kahn, 1990a, 1992).

A second, less visible implication of the traditional literatures is the

importance placed on how childhood factors shape authority relations

and, thus, authorizing dynamics. Both situational and personality researchers emphasize childhood factors. Milgram noted that one of the

crucial factors in obedience to authority was the socialization history

within one's family, whereas Zimbardo attributed the ease with which

subjects assumed roles to their experiences of power and powerlessness

relationships as children and parents. Individual-level researchers also

focus on childhood experiences, tracing the authoritarian personality to

particularly harsh, punishing parents (Adomo, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950) and drawing specific connections between upbringing and the characteristics of achieving, driven executives (Kaplan, 1991)

or neurotic leaders (Kets de Vries & Miller, 1987). Both approaches thus

emphasize childhood experiences as influential in authority dynamics,

although as yet neither has yielded a comprehensive framework that

describes the connections between people's early and later authority relations. Hirschhorn (1990: 541) hinted at one, when he noted that "internalized models of authority figures . . . derived from childhood" influence

authority relations at work (see Kahn, 1990b).

These implications help frame our approach to the authorizing and

de-authorizing processes that shape authority relations at work in both

traditional and collaborative organizational arrangements. Specifically,

we focus on how individuals authorize or de-authorize themselves and

others partly on the basis of enduring, often unacknowledged stances

toward authority itselfstances that are enacted in similar ways across

hierarchical and collaborative work arrangements and across various

roles and positions. These stances areas Hirschhorn (1990) suggested

infernaiized models developed in childhood that individuals typically

continue to carry into adulthood and which influence their authorizing

and de-authorizing of themselves and others in patterned ways. Drawing

24

Academy of Management Review

January

on recent theory and research in child development, we offer a framework

by which to understand such processes.

INTERNAL MODELS OF AUTHORITY

Clinical psychological research (Bowlby, 1980; Freud, 1936) suggests

that people tend to recreate the unresolved dynamics of past relationships (with parents, siblings, and other important figures) and act as if

those dynamics are part of present relationships (e.g., with spouses,

bosses, and co-workers). The psychoanalytic concept here is transference

(Freud, 1936): Impulses that have their source in early object relations are

not created by the objective situation but merely revived by the compulsion to repeat early relationships. The colloquial expression here is that

of the personal "baggage" that people carry with them to work and unload

on others. Clinical and developmental psychologists (Bowlby, 1980),

group dynamics theorists (Bennis & Shepard, 1956), and organizational

psychologists (Argyris & Schon, 1978; Hirschhorn, 1990; Kets de Vries &

Miller, 1985) have in various ways suggested a more technical version of

this dynamic: Individuals have internal models of authority that shape

how they experience and act in social systems. This notion builds on the

concept of theories-in-use (Argyris & Schon, 1978), but it adds both a sophisticated theoretical base (attachment theory) and a particular content

focus (authority relations).

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1973, 1980) focuses on how infants' early

attachments to primary caregivers determine enduring ways in which

they continue to attach themselves to significant others. On the basis of

experiences with primary caregivers, infants develop internal working

models of the world and particularly their relations to attachment figures.

More specifically, infants who develop secure models of attachment reflect caregiving environments that are stable, consistent, and nurturing,

whereas infants who develop insecure models of attachment are accurately reflecting caregiving environments in which nurturing is absent or

inconsistent. Internal models of attachment thus enable infants to carry

accurate pictures of their environments to guide their responses to primary caregivers (Bowlby, 1980; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Those

models guide behaviors and the appraisal of experience (Bowlby, 1973,

1980) and continue into adulthood (Weiss, 1982). Recent research suggests

that people's models of attachments influence ongoing relationships

other than those with parents and other primary caregivers (Hazan &

Shaver, 1987; Main et al., 1985). This is not to say that internal models

developed in childhood continue unabated or unchanged into adulthood,

but that aspects of those models continue to shape behavioral tendencies

and adult relationships.

Although these internal models of attachment are primarily about

autonomy and dependence in relationships (cf. Klein, 1959), they are implicitly about authority, given that parents and primary caregivers are the

1994

Kahn and Kiam

25

first authority figures in people's lives (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1973),

and they set the template for what people expect in authority relations.

Consider, for example, a person who had powerfully negative experiences with untrustworthy primary caregivers. Initially, the person will

maintain the belief that those in authority cannot be trusted. The person

may act as a subordinate in ways that are unauthentic and defensive,

and he or she may perceive others as manipulative and deceitful, so that

superiors will be forced to appear punitive and demanding as they seek

information and resources from the withholding subordinate. Similarly,

the person may act as a superior in ways that lead subordinates to withhold and defend themselves, allowing the person to confirm the belief

that others cannot be trusted. The person thus acts from a model of authority-as-untrustworthy to create untrustworthy authority relations. Like

self-fulfilling prophecies, people's internal models of authority are confirmed as they construct authority relations in ways that shore up those

models (Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985). Such cycles remain unbroken until

individuals enter meaningful relations of authority in which they are

given feedback and new experiences that weaken the hold of their internal models (described further in the following section).

Three points need to be emphasized here about such internal models,

as conceptualized in attachment theory. First, people may be more or less

aware of their internal models of authority, that is, of the nature of their

beliefs and how deeply embedded they are. Although people are typically

unaware of their internal working models (Bowlby, 1980; Main et al.,

1985; Sroufe & Fleeson, 1986), these models may become accessible to

individuals who understand the underlying patterns of their behavior in

relation with others. Individuals will therefore differ in terms of how consciously aware they are of their internal models. A second and related

point is that internal models tend to endure and shape people's relations

with others, unless people become aware of them and change them in the

context of meaningful relations with significant others and therapists

(Argyris & Schon, 1978; Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Sroufe, 1988). As models

become increasingly amenable to change, they exert less force on behavior and allow for situational influences (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Third, the

models are not of authority figures per se; they are of authority relations

(Kahn, 1990b)particularly of hierarchical relations, given that internal

models develop within the context of parent-child relations. Internal models of authority thus dictate how individuals will act in relation to one

another, in given or negotiated authority relations, irrespective of the

particular positions they occupy. The notion is that people strike various

poses or stances toward authority, regardless of who occupies authorized

roles.

Drawing on work from interpersonal (Argyle, 1967; Gabarro & Kotter,

1980; Hirschhorn, 1990; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985), group (Bennis & Shepard, 1956; Schein, 1979), and institutional (Miller & Gwynne, 1973; Turner,

1976) dynamics, we define three enduring stances toward the nature of

26

Academy of Management Review

January

authority: dependent, counferdependenf, and interdependent (see Table

1). Each stance is characterized by a set of assumptions about authority

and the principles on which relations of authority operate. These assumptions may be more or less explicit, depending on how aware individuals

are of their existence and operation. Internal models also are characterized by people's sense of self in relation to authority: beliefs about how

their personal selves are affected by relations of authority in hierarchical

systems. Like the assumptions about authority, these beliefs may be more

or less conscious. We also identify the patterns of attachment (Bowlby,

1973, 1980) to which the models correspond. Attachment theorists have

empirically documented three types of attachments between infants and

caregivers (Ainsworth, 1973). These types correspond to the three internal

models of authority in the next sections and are useful reference points for

understanding the formation of the operating strategies that adults use

(knowingly or not knowingly) to enact their internal models in relations

involving authority. Operating strategies are part of internal models, yet

they are observed through people's behaviors at work and in work relationships. The strategies guide people in enacting and reinforcing their

internal models of authority, leading to particular behavioral outcomes.

The following discussion highlights how people's internal models of

authority shape the relation between their personal selves and the hierarchical roles they occupy. The centrality of this theme reflects two converging notions. First, as noted above, authorizing is defined in terms of

giving the right to bring the personal self (one's own or another's) into the

work role. Second, an ongoing struggle for organization members is how

much they bring relevant dimensions of their personal, authentic selves

into task performances (Gould, 1993; Hirschhorn, 1985; Kahn, 1990a). Internal models of authority are thus patterns of how individuals resolve

such struggles in authorizing themselves and others to work. The three

internal models of authority described in the following sections each offer

different resolutions: to deny the need for bringing the self into the hierarchical role (suppress the self), to deny the need for the hierarchical role

itself (suppress the role), and to manage the ongoing relation between self

and role (suppress neither).

What follows are relatively pure forms of people's internal models of

authority described in terms that clearly distinguish them from one another. People's actions, beliefs, and feelings in relations involving authority may contain various shadings of the models and resemble aspects

of more than one of the models. Indeed, as people mature into adulthood

and participate in important relationships, they typically are able to revise their internal models and allow for behaviors usually associated

with other models (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). People thus mature so that they

have the capacity to take on aspects of multiple internal models and to

respond partly on the basis of situational cues. It is also the case, however, that aspects of people's childhood internal models are woven tightly

into their dispositions (Bowlby, 1973, 1980) such that they may be gener-

Kahn and Kiam

1994

27

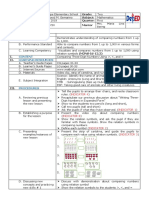

TABLE 1

Three Internal Models of Authority

Dependent

Stance toward

nature oi

authority

Emphasizes hieiaichical

roles of superior and

subordinate, whose

relationships are

governed by the rules of

iormal organizations.

Counterdependent

Undermines or dismisses

hierarchical roles of

superior and

subordinate.

Interdependent

Emphasizes interdependencies among

people occupying

various hierarchical

roles, acknowledging

both person and role

dimensions.

Authority itself is of

Authority itself is oi

Authority is a

Underlying

paramount importance.

minimal importance.

collaborative process.

assumptions

Relationships structured

Authority is suspect to the Different hierarchical

according to rules of

extent it undermines

positions offer diiierent,

personal expression.

equally valid, and

hierarchy.

complementary

Personal dimensions of

Nonrole data are

perspectives.

trustworthy.

people are suspect to

the extent they

Relationships structured in

undermine authority

terms of role and

personal dimensions.

relations.

Authority and personal

dimensions are linked;

one without the other is

suspect.

Sense oi seli

One's self is found

One's self is found outside One's seli is found in its

simultaneous

in relation

defined, constructed,

hierarchy and

dependence on and

to authority

maintained in

relationships of

independence from

relationships of

authority. In such

hierarchical

authority.

relationships, one's self

relationships of

Hierarchical position gives

becomes lost: engulfed

authority.

sense of self; without

or abandoned, denied or

such relationships, one's

suppressed, deself is lost.

constructed.

Corresponding Anxious resistant:

Anxious avoidant:

Secure:

pattem oi

Uncertain if others will

No confidence in others'

Confident in authority

attachment

be available,

helping, expects

relations, in which

responsive, helpful.

rejection. Seeks to be

others are available,

Tends to cling to

emotionally selfresponsive, and helpful.

authority relations,

sufficient, withdraws

Bold in exploring world:

anxious about exploring

from authority relations.

sense oi simultaneous

world.

connections and

independence.

Emphasize hierarchy,

Operating

Dismiss status diiferences, Emphasize person-in-role

status differences.

within hierarchical

strategies

de-emphasize hierarchy.

Encourage dependency,

relationships.

Rebel against authority

along hierarchical

Contribute personal

(own, others') with

thoughts, feelings

structures {in seli,

confrontation or

within authority

others).

withdrawal.

Idealize authority and its

interactions.

Deny dependency (in self,

representatives (in seli,

Acknowledge both

others).

personal and role

others).

Seek to pull self and

dimension (of self,

De-emphasize personal

others out oi role

relationships.

others).

thoughts and ieelings.

Emphasize simultaneous

dependence and

independence.

28

Academy of Management Review

January

ally characterized by one of the three general models described in the

following sections. In our analysis, we focus on these dispositional elements as they shape authority relations at work.

Dependent Model of Authority

We define the dependent model of authority in terms of people's dependency on the rules and roles of formal hierarchy. People whose internal models are of dependency tend to establish relationships in which the

dependency of the hierarchical subordinate on the superior is highlighted, sought, and valued. In Schein's (1979) terms, people seek conformity with established patterns of thought and behavior; in Turner's

(1976) terms, they adopt an "institutional" focus for their self. As subordinates, these people seek dependency on those in formal authority, deauthorizing themselves to take responsibility for managing themselves.

As superiors, these people seek the dependency of others over whom they

have authority, de-authorizing others to assume responsibility for managing themselves. They seek to structure relationships in terms of formalized relations between the roles that people occupy rather than between

the people themselves. As both superiors and subordinates, people with

dependent models of authority suppress their personal selves within such

role-based interactions. We suggest that this suppression is based partly

on their assumption that such personal dimensions inevitably undermine

the strict relations of authority on which they depend to guide their work

and work relationships. Given that assumption, they seek to split the

person away from the role and leave personal dimensions outside role

performances.

We also suggest that such dependency is based partly on people's

sense that they will find their identities only within the context of hierarchical relationships; that is, that their personal selves will find definition

only through the roles they occupy. Such self-definition is external. Employing this internal model, people depend on externally determined

rules and roles to guide their behaviors, beliefs, and feelings in relation

to others. It is within those role relations that people "find themselves,"

and it is outside those relations that people feel "lost." The dependence is

on the scripts attached to hierarchical roles that offer characters to portray (i.e., stereotypical characters of "boss" and "employee"), lines to say,

and plays to enact (cf. Fiske & Taylor, 1984). This model echoes the anxious resistant pattern of attachment (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1980), in

which infants who are uncertain about the availability of parents or primary caregivers tend to cling to those figures. These infants have anxiety

about exploring their world and wish to remain connected to authority

figures. Unless this type of internal model is replaced with another one,

the adults into which these children grow will maintain the desire to

remain connected both to authority figures and to authority itself, and

they will feel disconnected from internal guides of feelings, ideas, beliefs, and values.

1994

ifahn and Jfram

29

We posit that people with dependent models of authority have operating strategies to maintain their dependency and that of others. Their

strategies involve emphasizing the status differences between themselves and others with whom they are hierarchically affiliated and acting

in ways to reinforce such differences: Superiors act in ways that disempower or de-skill subordinates so they will be needed by those subordinates, and subordinates act in ways that disempower or de-skill themselves so that they consistently feel the need for their superiors. In doing

so, both superiors and subordinates with dependent models idealize authority and those in whom it is formally vested by organizations, and they

disparage the personal thoughts and feelings that people bring to relations of authority. In such a case, the ongoing deference to authority

one's own and that of othersis maintained at the expense of people

using their own thoughts, feelings, and beliefs to help guide their work.

What is left is simply the ongoing deference to authority. Behaviorally,

this means that people will suppressin themselves and othersreal

thoughts and feelings, spontaneously generated ideas, and the questioning of decisions based on personal values and ethical principles.

Counterdependent Model of Authority

We define the counterdependent model of authority in terms of people's resistance to the rules and roles of formal hierarchy. People whose

internal models are of counterdependency tend to establish relationships

in which authority itself is minimized, undermined, and de-valued (cf.

Schein, 1979, on rebellion). In Turner's (1976) terms, such people are "impulsives," who create their selves via spontaneous and often deviant

acts. As subordinates, these people dismiss or undermine hierarchically

determined role interactions; as superiors, these people similarly seek to

step outside the boundaries of role-determined relations. In each case,

hierarchical relations are de-authorized; that is, people are not given the

right to do work in the context of hierarchical relations. This deauthorization assumes various forms, ranging from the outright refusal to

cooperate in authority relationships (Schein, 1979) to the more subtle but

equally undermining substitution of personal connections for role-related

interactions with others (Hirschhorn, 1985, 1990), that is, undermining the

authority relations while maintaining or even emphasizing personal connections. As both superiors and subordinates, people with counterdependent models of authority thus seek to suppress authority.

Such counterdependency is based partly on people's sense that they

will find their identities only outside the context of hierarchical relationships and that they will be lost if fused with the roles they occupy (i.e.,

personal identity becomes de-constructed rather than constructed in rolebased relations). In such a case, the desired means of self-definition is to

resist external demands and to substitute countervailing personal behaviors, beliefs, and feelings. The scripts attached to hierarchical roles that

offer people characters to portray are ignored at all costs. This model

30

Academy ol Management Review

January

echoes the anxious avoidant pattem of attachment (Ainsworth, 1973;

Bowlby, 1980), in which infants who do not have confidence in parents or

primary caregivers, and expecting rejection from them, tend to distance

themselves from those figures. These infants have become emotionally

self-sufficient and suppress their needs for help from authority figures.

Unless this type of internal model is replaced with another, the adults into

which these children grow will maintain the desire to disconnect from

authority figures and from authority itself.

People with counterdependent models of authority have operating

strategies to maintain their dismissal of hierarchical role relations. Their

strategies involve de-emphasizing status differences. This constitutes rebellion against authority (one's own and others') that may occur in the

form of direct confrontation of authority or passive withdrawal from relationships involving the use of authority. Both types of behaviors are attempts to deny the dependency inherent in hierarchical relations. Such

behaviors also are, in Bion's (1961) terms, responses to anger at authority:

Active rebellion is the "fight" response, and passive withdrawal is the

"flight" response. Regarding the first response, organization members

struggle to topple the authority structure (and their places within it); regarding the latter response, they deny the existence of authority. In such

cases, people try to pull themselves and others out of the roles dictated by

hierarchy, explicitly or implicitly disparaging the structure and boundaries provided by authority relations and those who maintain them. The

ongoing undermining of authorityone's own and that of othersis

maintained at the expense of people's work connections and the organizational systems (of communication, accountability, responsibility, and

coordination) that support their tasks.

Interdependent Model of Authority

Finally, we define the interdependent model of authority in terms of

people's emphasis on both personal and role dimensions in working with

others who occupy different hierarchical positions. We suggest that people whose internal models are of interdependency tend to establish relationships in which there are aspects of both dependence on hierarchical

authority (one's own and others') and independence from that authority.

They assume that people occupy hierarchical roles and make valuable

contributions; as unique individuals, they can make such contributions

from the context of their roles. The interdependency is thus first between

person and role: Neither the person nor the role is suppressed in ways that

undermine how living, thinking, feeling people perform roles according

to the guiding structures and boundaries of hierarchical systems

(Hirschhom, 1990). This internal model assumes that people occupy given

roles and are neither subsumed by nor subsume those roles (Kahn, 1992).

The second interdependency is one across hierarchical levels of organizations: People seek to collaborate with others who occupy different

places for the inherently different perspectives they have on the perfor-

1994

Kahn and Jfram

31

mance of shared tasks (Gould, 1993; Hirschhorn, 1988, 1990). People with

this internal model trust in the value of both role and person, and they

believe in the usefulness of both authority and self-expression. Such people perceive hierarchical systems as offering different and complementary vantage points for perceiving, learning, and acting. It follows that

these people would seek to collaborate with others and value what they

offer from their own roles as subordinates and superiors. We believe the

two types of interdependencies are linked: As people seek to bring their

individual voices into the performance of their hierarchical roles, they

seek out the voices of others who are hierarchically linked to them.

Such interdependency is based partly on people's sense that they will

find their identities by being both inside and outside the context of hierarchical relationships. The premise is that people define themselves (i.e.,

construct their identities) partly in connection to established systems of

roles, boundaries, and authority, and partly in separation (even rebellion)

from those systems. Self-definition is achieved by both accepting and

resisting connections to authority (one's own and others'), just as people

define themselves partly in relation to and separate from others in close

relations (Smith & Berg, 1987). The image here is of actors who draw on

both given stage directions and their internal sense of the characters they

portray to enact their roles. This model echoes the secure pattern of attachment (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1980), in which infants feel confident

that parents or primary caregivers are consistently available and responsive to their needs while they maintain appropriate boundaries. These

infants are able to feel both self-sufficient and trusting in primary caregivers. The adults into which these children grow maintain the ability to

simultaneously connect with and remain separate from authority figures

and from authority itself.

People with interdependent models of authority act in ways, based on

their operating strategies, to emphasize the person-in-role. They do so by

using their own thoughts, feelings, and beliefs to help guide their task

performances and work interactions without discounting their roles or

those of others linked to them hierarchically (Kahn, 1990a). People's

voices and energies are employed in the context of roles and the service

of the tasks. In such cases, collaborations within and across levels of

responsibility and influence are sought. This means that people with

interdependent models of authority emphasize their simultaneous dependence on and independence from others. Such people acknowledge status

differences without making them so prominent that personal dimensions

(in self and others) are lost. Superiors and subordinates with interdependent models use the structure and boundaries provided by authority relations without letting themselves and their relations be dictated by those

systems.

It is clear from these descriptions that we conceive of the interdependent model of authority as containing the positive but not the negative

dimensions of the dependent and counterdependent models. Organiza-

32

Academy of Management Review

January

tion members with interdependent models of authority are able to emphasize both personal and role dimensions without sacrificing the integrity of either dimension in relations involving the use of authority. Organization members with either of the other two internal models will split

personal and role dimensions, emphasizing one at the cost of the other,

and they will not fully engage themselves in tasks and relationships at

work. We are making a clear normative statement here: People with interdependent models of authority are better able to authorize relevant

personal dimensions of themselves and others to work in roles of superior

and subordinate than people with either of the two other internal models

of authority we identify. Additionally, people with interdependent models

are better suited to the demands of the high involvement (Lawler, 1988)

and the postindustrial organization (Hirschhorn, 1988, 1990), which depend on the joint negotiation of duty and authority and the collaborations

that ensue.

LINKING INTERNAL MODELS OF AUTHORITY TO

BEHAVIORAL OUTCOMES

Internal models shape how individuals authorize and de-authorize

themselves and others as they take up organization roles, that is, to do the

work expected, to wield and be subject to influence, and to collaborate

with others within and outside hierarchical relationships. We focus here

on three specific areas in which such authorizing and de-authorizing occurs: task performance, hierarchical dyads, and teamwork. (Although

consideration of other outcomes is beyond the scope of this paper, they too

should be explored.) The first area focuses on individuals authorizing and

de-authorizing themselves to work; the second area focuses on authorizing and de-authorizing in both traditional superior-subordinate and mentoring relationships; and the third area focuses on authorizing and deauthorizing in traditional and self-managing work groups. For each area,

we offer propositions about how people's tendencies to act on the basis of

aspects of internal models of authority shape their behaviors.

Task performance. How hard organization members work on assigned tasks is traditionally understood in terms of work motivation: how

much people are compelled to perform capably by external (e.g., financial incentives) and internal (e.g., growth opportunities) rewards for doing so. Organizations traditionally seek to strengthen their employees'

motivations by enhancing reward systems (Steers & Porter, 1979) and job

characteristics (Hackman & Oldham, 1980) in order to encourage employees to work more productively. Underlying the work motivation approach

is a lingering assumption of Taylor's (1911) scientific management: Employers can find the correct motivaters that activate the employee's energies to perform standard, externally-directed laborsmuch as one

would activate a machine. The heightened pace of work and change in

modern organizations increasingly renders this assumption obsolete, as

1994

Kahn and Kiam

33

does the need for employees to simply release energies and effort in the

service of directed tasks. Increasingly, employees need to create new

methods and ideas, to direct themselves, to collaborate across roles and

hierarchical levels, and to think more critically and autonomously

(Handy, 1989; Hirschhorn, 1990; Lawler, 1988). To do so, organization members must be more psychologically present at work. They must feel and be

attentive and connected to their tasks and others, have various parts of

themselves accessible rather than split off and inaccessible to their work,

and focus on bringing those parts to the primary task. Most important,

they must be recognized and rewarded for being present in such ways.

The new language is of presence, which subsumes the vocabulary of

work motivation.

There are various influences on the extent to which organization

members are psychologically present at any moment in time. Kahn (1992)

described both systemic (or situational) and individual influences, the

latter including internal models that individuals have of themselves in

their roles (i.e., models of themselves as psychologically present or absent). He noted that individuals vary in terms of how much they authorize

themselves to bring their personal selves into their task performances,

and he suggested that such "self-authorizations" are based partly on internal models on which people consciously or unconsciously depend to

guide their work relations. We extend that argument here, first noting

that there are actually two authorizing dynamics involved: authorizing of

the role (i.e., supporting role-dictated behaviors) and authorizing of the

person (i.e., supporting the bringing to bear of personal dimensions

thoughts, feelings, creative impulses, values, and beliefsto tasks). We

suggest that each of the three internal models of authority has particular

implications for the extent to which organization members authorize the

presence of role and personal dimensions during task performances, for

themselves and others.

More specifically, we suggest that people with dependent models

will tend to authorize themselves and others to act from their roles during

task performances, and they will de-authorize themselves and others to

draw on personal dimensions in guiding those performances. These people will accept the parameters of given rolestheir own and others'

and will seek direction from existing norms of thought and action rather

than create new methods and ideas, direct themselves, and think critically and autonomously. People with counterdependent models, conversely, will tend to de-authorize work rolestheir own and others'by

directing behaviors away from the purposes of given roles. Such people

may do so through clear rebellion (e.g., simply doing or encouraging

things contrary to role purposes) or through more subtle underminings

(e.g., playing upon personal relationships to reshape expected role behaviors). These people are more likely to create new methods and ideas,

to direct themselves, and to think critically and autonomously (i.e., authorize personal dimensions of oneself and others), but often in the ser-

34

Academy of Management Review

January

vice of de-authorizing given roles. Finally, we suggest that people with

interdependent models will tend to authorize both role and personal dimensions of themselves and others. These people are most likely to create

new methods and ideas, to direct themselves, and to think critically and

autonomously in the service of meeting (and exceeding) expectations

about role-dictated behaviors. These people will resist impulsestheir

own and others'to emphasize either role or personal dictates, such that

one inappropriately eclipses the other.

Proposition 1: People with dependent internal models of

authority will authorize role-dictated behaviors and deauthorize personal dimensions of themselves and others

during task performances.

Proposition 2: People with counterdependent internal

models of authority will de-authorize role-dictated behaviors (and may authorize personal dimensions) of

themselves and others during task performances.

Proposition 3: People with interdependent internal models of authority will authorize both role-dictated behaviors and personal dimensions to coexist during task performances, so neither one is emphasized at the expense

of the other.

These three propositions form the basis for the propositions that follow.

Hierarchical dyads. The majority of hierarchical dyads generally take

one of two forms in organizations: those that are formally prescribed by

the organization to support task performance (e.g., boss-subordinate relationships), or those that evolve naturally to support the junior member's

learning and development (e.g., mentor relationship). Though the latter

may be formally assigned through a human resource initiative, more

often such relationships occur through the voluntary involvement of both

parties. Although some formally prescribed boss-subordinate relationships also may evolve into a mentor relationship, they are discussed

separately here.

In formal hierarchical relationships, the internal models of authority

that one individual brings to the dyad may converge or diverge from that

of the other, with differing implications. We suggest that when both boss

and subordinate have dependent models of authority, for example, they

each invest energy into suppressing personal dimensions of themselves

that are relevant to their work together. This may include suppressing

creative ideas, ethical questions, or feelings whose absence may impede

communication or undermine work effectiveness. If both boss and subordinate have counterdependent models of authority, they may collude in

dismissing the importance of hierarchical relationships and, in doing so,

undermine the extent to which the boss assumes real responsibility for

1994

Yiahn and Kiam

35

the completion of assigned tasks. When both members of the dyad have

interdependent models of authority, they are able to construct a relationship that guards against these dangers. In these relationships, each person is able to engage the relevant personal dimensions of himself or

herself and the other within the context of their respective roles.

Proposition 4: When both dyad membeis hold either dependent or counferdependenf internal models of authority, the relationship will undermine task performance

through the joint suppression of persona] dimensions of

selves or denial of responsibiiity and expertise.

Even though hierarchical dyads will be limited in their effectiveness

when either dependent or counterdependent models are imported by both

members, there is a degree of fit because both parties' assumptions, expectations, and strategies are complementary. When dyad members

bring different models of authority to the relationship (i.e., a poor fit), we

can anticipate quite different results (Gabarro & Kotter, 1980). For example, if an organization member wishes to undermine authority and his or

her superior wishes to emphasize authority, the two will construct a relationship in which each is at odds with the other; a play will commence

whose plot is insubordination and whose resolution will involve the undermining of participants, the relationship, and the work itself. Similarly,

if a subordinate wishes to cling to a superior who eschews his or her own

authority and those who demand it, the effectiveness of each is again

undermined along with their relationship and their work. In each of these

cases (and in the other possible combinations of the three internal models

previously described) the operating principle is the same: The lack of fit

between the superior's internal model and that of the subordinate creates

actual relationships that undermine rather than support their work.

Proposition 5: Dyad members will experience inteipeisonal conflict, dissatisfaction, and difficulties with task

performance when membeis biing different internai

models of authority to the ielationship.

The internal models that organization members hold also influence

the extent to which they seek out and maintain mentoring relationships,

which hold the promise of substantial task and personal learning (Hall &

Kram, 1981; Kram, 1988; Kram & Bragar, 1992; McCall et al., 1988; Schein,

1978). In the early career years, novices face the challenges of establishing a work identity and niche, developing self-confidence, acquiring relevant competencies and knowledge, and preparing for advancement and

growth (Hall, 1976; Schein, 1978). Dependent individuals will readily seek

mentors' advice and counsel, whereas counterdependent individuals are

more likely to attempt to master these same challenges alone. It may also

be that those with dependent stances are resistant to entering the separation phase of the relationship, holding on to a dependency that thwarts

independence and growth over time. Alternatively, whereas counterde-

36

Academy of Management Review

January

pendent individuals may overcome resistance to seeking help, they may

be relatively unwilling to risk the self-disclosure that fosters the cultivation of deep mentoring alliances.

Similarly, those in the middle and late career years will face the

predictable tasks of reassessment and redirection, the threats of obsolescence and aging, and the opportunities to become generative through

assuming the mentor role (Kram, 1988; Levinson, Darrow, Klein, Levinson,

& McKee, 1979; Schein, 1978). Again, it will be difficult, we suspect, for

those with a counterdependent stance to develop deepened relationships

with fledgling (and dependent) proteges. Similarly, it will be difficult for

these same individuals to ask for help in addressing the critical challenges of midlife and increasing organizational turbulence.

Proposition 6; /ndividuais with dependent models of authority will more actively seek mentoring relationships

than those with counterdependent models of authority.

Proposition 7: Both dependent and counterdependent

models undermine the potential value of mentoring relationshipsthe former thwarts movement through the

separation and redefinition phases, and the latter

thwarts the degree of intimacy and personal learning

that can occur.

It appears ultimately that an interdependent stance holds the greatest potential for deepening mentoring alliances in which mutual benefits

of such developmental alliances are maximized. In this case, both parties

are willing to share relevant personal dimensions, to acknowledge and

work with hierarchical/status differences created by the formal roles they

occupy, and to collaborate regarding both task accomplishment and personal learning.

Teamwork. Teamwork has become increasingly important in contemporary organizations, and task forces and self-managing groups are commonplace (Hackman, 1987). Thus, in addition to traditional work groups,

effective teamwork (group members jointly applying knowledge and

skills to accomplish objectives that are acceptable to those who receive or

review task output) (Hackman, 1987) is now essential to interdepartmental

coordination, product innovation, and a variety of other critical organizational tasks. We suggest that individuals' internal models of authority

will shape their participationtype and amount of effort, roles, strategies for participatingacross various types of groups.

For example, in the traditional work group, we can expect that the

dependent individuals will welcome direction from a formal group leader

(e.g., the boss) and also will have the tendency to de-authorize themselves and their peers. As a consequence, members' creative contributions to task performance will be thwarted. We can anticipate that these

same individuals will have more difficulty with self-managing groups

1994

Kahn and Kiam

37

and task forces, where formal authority is not prescribed, and, instead,

group members must coUaboratively work toward accomplishing tasks

while authority is shared among members. In order for such individuals

to effectively contribute in this context and also facilitate other members'

contributions, they will have to contend with considerable discomfort and

move beyond the dependent stance.

Proposition 8; Group members with dependent models

of authority will simultaneously desire direction and

support from the boss (and other formal authority), and

they will discount their own authority and that of their

peers.

In contrast to dependent individuals, the group member who holds a

counterdependent model of authority will welcome the opportunity to participate in a self-managing group where members are expected to operate

autonomously. However, it is also likely that while embracing their own

skills, voice, and authority, such members will resist other members'

attempts to provide leadership for the group. Also, if most members hold

this stance, there is a good likelihood that the group will distance itself

from its formal leaders and sever lines of support and communication that

are important to its task effectiveness.

Proposition 9: Group members with counterdependent

models of authority will distance themselves from their

formal leaders, resist the authority of other group members, and may. to varying extents, embrace their own

voices and creative energies.

This analysis suggests that group members with either internaJ

model of authoritydependence or counterdependenceare likely to

undermine (to some degree) the potential of traditional work groups, task

forces, and self-managing work groups. The implication here is that

members who hold an interdependent model of authority will be most

effective in maximizing effective task performance in groups. Such individuals seek collaborative relations between hierarchical levels: They

are able to draw upon formal systems of authority, communication, and

control for support, guidance, structure, and resources. At the same time,

they also are able to assume ownership for task processes and outputs,

and they will encourage their peers to do the same. This sense of ownership seems particularly important to the success of self-managing

groups, whose members must take personal responsibility for work outcomes, monitor their own performances, take corrective actions when

necessary, actively seek guidance from their organizations when necessary, and help other people in other areas to improve their performances

(Hackman, 1986). Self-managing groups need members who are willing

and able to take ownership of their own processes, and in doing so authorize both themselves and others. As organizations necessarily rely

38

Academy of Management Review

January-

more and more on self-managing teams for innovation, quality, and productivity, they will need members who bring an interdependent stance to

teamwork.

Proposition 10: Group members who hold an interdependent model of authority are most capable of utilizing

resources within and outside the group toward achieving teamwork and organizational objectives.

This set of propositions offers a way to begin mapping the influence

that organization members' internal models of authority have on their

work and work relationships.

TRIGGERING AND CHANGING INTERNAL MODELS OF AUTHORITY

In explicating the nature and influence of internal models of authority, we have simplified the three models, treating them as though they are

constant and enduring (i.e., always operating and impervious to modification from birth). Neither point is accurate; the reality is more subtle and

complex. Next, we offer propositions about how internal models of authority might be triggered and how they might change at work.

Triggering Internal Models of Authority

It is likely that there are real individual differences in terms of how

dominant an internal model of authority is over a particular person's

behavior. Some individuals, for example, may be influenced a great deal

by their internal models, across various situations, whereas others may

be influenced to lesser extents, in particular and discrete situations. That

is, some people will automatically respond to many situations with the

strategies dictated by their internal models, whereas other people will

automatically respond to just a few situations and in the other situations

they will have a wider range of choices about how to behave. We understand these differences in terms of how often an individual's internal

model is triggered. People will vary along this dimension, from those

whose models are triggered so often that they seem to react to all situations with the automatic application of their models, to those whose models are triggered so infrequently that it seems a behavioral aberration

when they are. We use the concept of triggering as a way of exploring

more deeply why internal models are activated, in terms of the functions

they serve for individuals.

Our premise is that it is when individuals experience enough anxiety

to make them feel insecure in their immediate situations that their internal model of authority is triggered. This idea reflects two principles from

research and theory on attachment. First, infants (Bowlby, 1973), youths

(Cicchetti, Cummings, Greenberg, & Marvin, 1990), and adults (Weiss,

1982) selectively enact their models of attachment in situations in which

1994

Kahn and Jfram

39

they experience anxiety. Those situations invariably occur when people

feel that their sense of security is threatened, that is, when the world does

not seem predictable and familiar and the person's way of navigating

through emotions and situations is threatened. Second, internal models

function to provide security. When individuals feel threatened, they enact

behaviors whose aim is to re-create the sense of security (Ainsworth,

1973); that is, they cling to, withdraw from, or reestablish connection and

then move away from attachment figures so as to create a relationship

that is familiar and comfortable. This notion leads to the following proposition:

Proposition i i : Organization membeis operate from

tiieir internal models of aufiiority when they experience

work situations as insecure: They cling to (dependent),

push away from (counterdependent). or establish ties

while remaining independent of (interdependent) given

roles and authority relations until they again feel secure.

When do organization members experience the threat and anxiety

that triggers their internal models? There are many sources of stress in

organizational life, ranging from traditional sources such as task and

interpersonal demands (Cooper & Payne, 1978) to postindustrial sources

such as increasing competition, cost-reduction initiatives, the speed and

complexity of tasks, and the demands of collaboration (Handy, 1989; Hirschhom, 1990). The ambiguous structure of high-involvement systems

(Lawler, 1988) itself creates stress, as individuals experience the absence

of the traditional hierarchical structure and the relative sense of security

it offered. Such stressors do not automatically lead to experienced threat

and anxiety nor to individuals' searches for security. Rather it is when

individuals perceive events and situations as threatening to their sense of

security that they will feel threatened and anxious and behave accordingly (Lazarus, 1966). Such perceptions are based both on how others

perceive and react to situations and on individuals' tendencies to perceive their situations in particular ways.

Norms. Group and organizational norms exert pressures on how

members "ought" to respond to situations (Hackman, 1976). They also

shape how system members frame or interpret situations, in terms of how

familiar or threatening the situations are and what sorts of responses they

should call forth. When the prevailing norms dictate that certain situations (e.g., CEO succession) be treated as nonthreatening, it is less likely

that system members' internal models will be triggered. When norms

dictate that other situations (e.g., union-management impasse) be treated

as threatening, it is more likely that members' internal models will be

triggered.

In these latter situations, there are also norms about the "appropri-

40

Academy of Management Review

January

ate" ways to respond to threat, which presumably serve to create a sense

of security in threatening situations. Appropriate responses may include

members clinging to, pushing away from, or acting within while remaining partly independent of given roles and authority relations. For example, one organization's norms may encourage members to withdraw or

undermine their roles in expressions of resentment (counterdependent),

whereas another organization's norms may encourage members to put in

more hours on their tasks but not to expend energies in thinking critically

and autonomously about those tasks (dependent). Though such norms

function (from the organization's perspective) to enable members to experience solidarity and comfort with one another, they also may produce the

opposite effect: Individuals' own internal models of authority fit or do not

fit with the strategies required by the norms of their units, which presumably leads to implications for members' experiences of security within

those units. This idea suggests the following proposition:

Proposition 12: Individuals with internal models of authority that fit with normative responses will have a diminished sense of anxiety, threat, and insecurity: individuals with counternormative internal models and who

are unable to adapt their behaviors will continue to feel

threatened and insecure.

Personal insecurity. Individuals also differ in terms of how secure or

insecure they tend to feel, across various types of situations and relationships. That is, people differ in terms of how often they frame situations

and events as threatening and, therefore, how often they feel anxious and

insecure (Greenspan & Lieberman, 1988). Individuals who experience insecurity often, across situations, are likely to activate their particular

internal models of authority often in order to try and create familiar relationships by which to feel secure (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1980). Thus,

these people will approach a great many situations by automatically

clinging to, pushing away from, or acting within while remaining independent of given roles and authority relations. Because their models are

triggered by "clues" that are generated internally rather than perceived

externally, their actions may be completely inappropriate to the actual

dictates of the situation, such as when an insecure person attempts to

cling to the rules of hierarchical relations in an explicitly collaborative

context (e.g., self-managing team). This notion leads to the following

proposition:

Proposition 13: Insecure individuals may project rather

than perceive actual threats to their personal security

and thus activate behaviors that are unproductive for

their work and work relationships.

1994

Kahn and Kiam

41

Changing Internal Models of Authority

We have suggested that when internal models of authority are triggered, individuals act automatically. The point of changing these models, then, is to offer individuals a more conscious choice about how they

wish to behave in particular situations (i.e., to expand the range of behaviors they may apply to different situations). We assume that each of