Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Evaluate Treat Mild Feeding Delays Limitations

Uploaded by

Carmen Cuevas0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views2 pagesChildren with mild sensorimotor problems may show delays or difficulties with feeding. Dr. Sanjay gupta: Why might we still evaluate and TREAT MILD FEEDING DELAYS AND limitations? he says feeding movements are closely related to the oral movements that children use in early speech development.

Original Description:

Original Title

feeding.6

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentChildren with mild sensorimotor problems may show delays or difficulties with feeding. Dr. Sanjay gupta: Why might we still evaluate and TREAT MILD FEEDING DELAYS AND limitations? he says feeding movements are closely related to the oral movements that children use in early speech development.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views2 pagesWhy Evaluate Treat Mild Feeding Delays Limitations

Uploaded by

Carmen CuevasChildren with mild sensorimotor problems may show delays or difficulties with feeding. Dr. Sanjay gupta: Why might we still evaluate and TREAT MILD FEEDING DELAYS AND limitations? he says feeding movements are closely related to the oral movements that children use in early speech development.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Children with mild sensorimotor problems may show

delays or difficulties with feeding that do not limit

their ability to eat in clearly observable ways. Thus, if

a child is able to chew, eats a wide variety of foods, and

does not choke on food, many parents and professionals think that there are no feeding problems. This is not

always true. Why might we still evaluate feeding skills

and include feeding goals in an educational or therapy

program? In order to answer these questions, it is

helpful to look at the connection between feeding and

other areas of development.

WHY EVALUATE

AND

TREAT MILD FEEDING

DELAYS

AND

LIMITATIONS

Feeding movements are closely related to the oral

movements that children use in early speech development. Many believe that feeding movements provide

the actual patterns which children learn and refine for

speech sounds.

Feeding skills require a high level of sensory organization and integration. When children have difficulties with sensory processing skills, feeding may

become impaired in very subtle ways. This may be

expressed in dislike of certain food textures or tastes

and a reluctance to try new foods.

Feeding skills are used in social situations. A child

who drools during meals or in the classroom is often

shunned by classmates or adults. Children who are

messy eaters call attention to their disability in restaurants and in social situations with typically developing

children. Thus, even a mild feeding problem can have

consequences in daily social situations.

Children with sensorimotor difficulties tend to fall

into two major categories of oral sensorimotor problems that will be identified during feeding.

Sensorimotor Control. Some children have delays

in feeding development (i.e. retained suckle,

unstabilized up-down jaw movement exclusively during drinking, lack of cleaning the lips with the teeth or

tongue), or deviant/limiting patterns during feeding

(i.e. low tone in the cheeks which prevents active

asymmetrical pull-in of the cheek on the side of the

food, lip retraction, lack of central groove in the tongue).

These children have difficulty controlling the movements used for feeding.

Sensorimotor Planning. Other children have appropriate feeding movements but cannot make the same

movements at a volitional level (i.e. the child is observed to use the tongue to clean pudding from the

corner of the mouth but cannot lateralize the tongue in

imitation). These children have difficulty with motor

planning or apraxia.

Suzanne Evans Morris, Ph.D.

Speech-Language Pathologist

New Visions

1124 Roberts Mountain Road

Faber, Virginia 22938

(804) 361-2285, sem@new-vis.com

Revised: January 1998

Foods with multiple textures. Foods which consist

of more than one texture are very challenging to children. Some foods have two or more textures which can

be visibly observed; others tend to produce extra juice

or saliva when they are chewed. The child must swallow the liquid and extra saliva produced by the food

while continuing to chew the more solid parts. Often

children with mild difficulties in oral-motor skill will

drool or loose liquid when they eat combination foods.

Foods which could be given at snack time include:

unpeeled apple wedges ; orange wedges; raisins; jello

with fruit chunks, non-mushy dry cereal such as Cheerios or small shredded wheat squares with milk; salad

with pieces of different raw vegetables.

It is important to constantly ask ourselves why we are

interested in feeding evaluation and intervention with

these mildly involved children. When we ask that

question, two further questions with answers emerge.

Could the movement and coordination patterns

observed in the mouth during feeding help us understand the movement and coordination patterns observed in the mouth during speech?

Do the sensorimotor patterns observed with food

reflect in any way the more general sensorimotor

organization used by the child?

Both of these questions influence treatment decisions.

For example, if we see low tone in the cheeks and/or in

the tongue and the child has a sloppy /s/ sound, it

lets us know that work to improve cheek and tongue

function in feeding would assist getting better phonological production of these fricative sounds. Or, if we

see a child who has many picky dislikes of food texture

or taste, or stuffs and gulps everything, we may see this

same type of sensory processing in the childs whole

learning style. Thus, work on the underlying sensory

issues and focus of attention and slowing of feeding

patterns may very well become a way of working on an

underlying basic skill which will also generalize into

the childs ability to use language and learn more

efficiently.

Foods which require extended chewing. Foods

which require extended chewing are often resisted by

children with mild feeding problems. At home they

are often given softer meats or no meats or raw vegetables at all because they refuse them. Foods which

could be given at snack time to increase chewing skill

include: raw carrots, raw celery, beef jerky, strips of

rare roast beef, steak, or other firm meat. Although

candy and other sweet foods should be discouraged as

a regular snack, liquorice twists and sugar-free bubble

gum are wonderful for encouraging extended chewing, and chewing without drooling.

Foods which can be served in many sensory

variations. Foods which can be served in many different taste and texture combinations lend themselves

beautifully to work on sensory discrimination and

language. They also provide ways of making smaller,

more gradual changes for children who are resistant to

eating new foods. Foods which could be given at

snack time to focus on sensory changes in taste and

texture include: crackers + peanut butter; crackers +

Swiss cheese; crackers + cheddar cheese; crackers +

cream cheese; crackers + cream cheese + jelly. Or one

could take a theme of cheese and vary the type of

cracker used (i.e. Ritz cracker, soda cracker, rice cake,

rye krisp).

Work to improve feeding skills can be incorporated

into both the individual therapy session and in the

classroom. Feeding skills are sensorimotor skills, and

like other sensorimotor skills such as sitting, and walking, and hopping, children may require special therapy

assistance to learn a new or unfamiliar movement.

Often new patterns of chewing or swallowing will be

taught initially by a therapist or teacher with special

skill or training in the learning of feeding skills.

As new skills develop, children need lots of opportunity to practice the new patterns. The classroom

provides many opportunities for continued learning

and change. Snack time occurs in every classroom.

Often it is considered a time to physically refresh the

children with food or an opportunity to work on

language and social skills. When food is carefully

selected, snack time can provide major opportunities

to develop sensorimotor skills for feeding.

Foods which encourage playful exploration.

Exploration with food is a common activity with young

children in the 18-36 month age range. Children enjoy

hiding pieces of food in different parts of the mouth,

feeling the mouth stuffed with food, playing with

differing amounts of food in the mouth etc. Foods

which encourage exploration include: raisins, cereal

pieces such as Cheerios and Grape Nuts. Chewing

sugar-free bubble gum also develops playful exploration.

Food can be selected to meet specific goals for individual children and to provide opportunities for all

children in the group to increase their experience with

different kinds of food. Several types of food and

utensils provide excellent opportunities for children

with sensorimotor difficulties:

Copyright New Visions

This paper is a working draft and multiple copies may not

be reproduced without prior written permission of the

author.

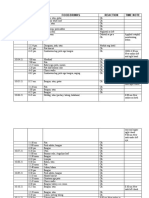

You might also like

- How To Improve Feeding Skills in Children: Ma/Ccc-Slp Jeremi Grosser MS/CCC-SLPDocument19 pagesHow To Improve Feeding Skills in Children: Ma/Ccc-Slp Jeremi Grosser MS/CCC-SLPjhebetaNo ratings yet

- Feeding Pre-Speech Characteristics: Observed in Children With Mild Sensorimotor DisabilityDocument4 pagesFeeding Pre-Speech Characteristics: Observed in Children With Mild Sensorimotor DisabilityCarmen CuevasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document16 pagesChapter 7Siamak HeshmatiNo ratings yet

- Autism and Mealtime ChallengesDocument6 pagesAutism and Mealtime ChallengesCon SentidosNo ratings yet

- Child Nutrition PresentationDocument26 pagesChild Nutrition Presentationapi-297995793No ratings yet

- Feeding Strategies For Older Infants and Toddlers: Sensory Skills, Which Allow The Older Infant and ToddlerDocument6 pagesFeeding Strategies For Older Infants and Toddlers: Sensory Skills, Which Allow The Older Infant and Toddlermarkus_danusantosoNo ratings yet

- Feeding Strategies For Older Infants and ToddlersDocument6 pagesFeeding Strategies For Older Infants and Toddlersxxxxxx100% (2)

- Info Sheet Feeding Disorders 6 17Document3 pagesInfo Sheet Feeding Disorders 6 17Saja MuhammadNo ratings yet

- FeedingDocument9 pagesFeedingVarvara MarkoulakiNo ratings yet

- Autism and Food RelationshipDocument46 pagesAutism and Food Relationshipapi-267309034100% (1)

- csd625-f13 Canvas Mod5Document15 pagescsd625-f13 Canvas Mod5api-242414162No ratings yet

- Arwen Jackson and Jacklyn Kammerer - Professional Lecture - Feeding and Swallowing in The Medically Complex Infant With Down Syndrome - EnglishDocument41 pagesArwen Jackson and Jacklyn Kammerer - Professional Lecture - Feeding and Swallowing in The Medically Complex Infant With Down Syndrome - EnglishGlobalDownSyndromeNo ratings yet

- Activities of Daily Living 2022Document65 pagesActivities of Daily Living 2022Namakau MuliloNo ratings yet

- Feeding Your Baby 6-12monthsDocument35 pagesFeeding Your Baby 6-12monthsoana535No ratings yet

- Oral Motor SkillsDocument4 pagesOral Motor SkillsYOHAN FERNANDONo ratings yet

- Feeding GuideDocument6 pagesFeeding GuideDorneanu Alexandru100% (1)

- Caregiver EducationDocument6 pagesCaregiver Educationapi-494142720No ratings yet

- Preschool NutritionDocument31 pagesPreschool NutritionRaseldoNo ratings yet

- Get Up & Grow Healthy Eating and Physical Activity For Early ChildhoodDocument3 pagesGet Up & Grow Healthy Eating and Physical Activity For Early ChildhoodPatrick FormosoNo ratings yet

- BabySolidFoods Nov2012Document24 pagesBabySolidFoods Nov2012SK WasimNo ratings yet

- Feedinginfants ch2Document4 pagesFeedinginfants ch2Charles BangetNo ratings yet

- Feeding Your Child 6 12monthsDocument12 pagesFeeding Your Child 6 12monthssarahann080383No ratings yet

- When Children Wont EatWhen Children Won't Eat: Understanding The "Why's" and How To HelpDocument4 pagesWhen Children Wont EatWhen Children Won't Eat: Understanding The "Why's" and How To Helpxxxxxx100% (1)

- Eating Difficulties in Children and Young People With DisabilitiesDocument32 pagesEating Difficulties in Children and Young People With DisabilitiesWasim KakrooNo ratings yet

- Food For Baby's First Year: Family and Consumer Sciences Fact SheetDocument2 pagesFood For Baby's First Year: Family and Consumer Sciences Fact SheetPramesliaNo ratings yet

- Black HurleyANGxp Rev EatingDocument10 pagesBlack HurleyANGxp Rev Eatingann88michNo ratings yet

- London Metropolitian University NutritionDocument8 pagesLondon Metropolitian University Nutritionmicky mouseNo ratings yet

- AOTA Handout - Establishing Mealtime Routines For ChildrenDocument2 pagesAOTA Handout - Establishing Mealtime Routines For ChildrenAble BatangasNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Child Development SlidesDocument34 pagesNutrition and Child Development SlidesSamson KisenseNo ratings yet

- Picky Eaters PrintingDocument62 pagesPicky Eaters Printingapi-307937897No ratings yet

- 122 OralMotorDevelopmentalMilestonesDocument2 pages122 OralMotorDevelopmentalMilestonesMaithri SivaramanNo ratings yet

- 2 1 EriksonDocument3 pages2 1 EriksonkemimeNo ratings yet

- Feeding Behavior Guide 1Document6 pagesFeeding Behavior Guide 1IgorNo ratings yet

- ToddlerDocument11 pagesToddlerLian QuilbioNo ratings yet

- Management of Food JagsDocument4 pagesManagement of Food JagsHermiNo ratings yet

- Ped Basics Feeding Gerber 110 Fall 2002Document27 pagesPed Basics Feeding Gerber 110 Fall 2002Talavera Clau100% (1)

- ANNISA ENDAH DK - P07131219033 - Task 1Document14 pagesANNISA ENDAH DK - P07131219033 - Task 1Annisa Endah Dwi KurniaNo ratings yet

- Fshn322groupproject FinalDocument15 pagesFshn322groupproject Finalapi-241264551No ratings yet

- Nutrition (1) PresentationDocument15 pagesNutrition (1) PresentationSaminaShahid123No ratings yet

- Nourishing Your Child: A Guide to Overcoming Eating Problems: Health, #11From EverandNourishing Your Child: A Guide to Overcoming Eating Problems: Health, #11No ratings yet

- Exploring Feeding BehaviorDocument6 pagesExploring Feeding BehaviorristeacristiNo ratings yet

- Picky Eaters vs. Feeding Disorders: Recognizing The DifferencesDocument33 pagesPicky Eaters vs. Feeding Disorders: Recognizing The DifferencesRohit BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Promoting Nutritional Health of The PreschoolerDocument3 pagesPromoting Nutritional Health of The Preschoolerezyl twotownNo ratings yet

- Weaning to Dining: Baby's First Bites to Family Meals: Baby food, #5From EverandWeaning to Dining: Baby's First Bites to Family Meals: Baby food, #5No ratings yet

- Breakfast, Lunch and Snack Ideas: For Elementary StudentsDocument19 pagesBreakfast, Lunch and Snack Ideas: For Elementary StudentsTang Xin YuanNo ratings yet

- Eat Right, Grow Strong: Nutrition For Young ChildrenDocument35 pagesEat Right, Grow Strong: Nutrition For Young ChildrenDipayan MondalNo ratings yet

- The Early Food Environment Week 18Document7 pagesThe Early Food Environment Week 18Rhea RaichuraNo ratings yet

- Human Eating BehaviorDocument2 pagesHuman Eating Behaviorkevine atienoNo ratings yet

- Gillian Harris Selective Eating in Children With AutismDocument43 pagesGillian Harris Selective Eating in Children With AutismAnna KrauzeNo ratings yet

- Nutrition: To Support Healthy Eating Habits at Home Try Some of The Following StrategiesDocument1 pageNutrition: To Support Healthy Eating Habits at Home Try Some of The Following StrategiesShawna PassmoreNo ratings yet

- Complementary Foods by WhoDocument30 pagesComplementary Foods by WhoachintbtNo ratings yet

- Banana Cake RecipeDocument3 pagesBanana Cake RecipeEvelyn SantosNo ratings yet

- 90 - Comparative and Superlative Adjective Stories - CanDocument11 pages90 - Comparative and Superlative Adjective Stories - CanDiana Yasmín Hernández B.No ratings yet

- Methods of Manufacture of Fermented Dairy ProductsDocument25 pagesMethods of Manufacture of Fermented Dairy ProductsRonak RawatNo ratings yet

- Arax Restaurants: These Factors IncludeDocument8 pagesArax Restaurants: These Factors Includesanjay patilNo ratings yet

- Panlasang PinoyDocument25 pagesPanlasang PinoyMiame Luna KilatonNo ratings yet

- Food DiaryDocument4 pagesFood Diarymila bediaNo ratings yet

- M2 S4 Part1Document3 pagesM2 S4 Part1Dhouha BabaNo ratings yet

- David's Cinnamon RollsDocument2 pagesDavid's Cinnamon RollsDB ScottNo ratings yet

- Types of ServiceDocument21 pagesTypes of ServiceJoise AlexaNo ratings yet

- Molly's Tea RoomDocument6 pagesMolly's Tea RoomAngel TorresNo ratings yet

- Ways of EatingDocument11 pagesWays of EatingDenise MartinsNo ratings yet

- Nandos Menu PDFDocument2 pagesNandos Menu PDFsnamprogNo ratings yet

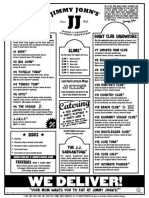

- Jimmy Johns MenuDocument1 pageJimmy Johns Menuomer farooqNo ratings yet

- Ganache EbookDocument40 pagesGanache EbookAdriana Nistor50% (2)

- Win The War Cook BookDocument172 pagesWin The War Cook BookSandra MianNo ratings yet

- Samosa Chaat Recipe BBC Good FoodDocument1 pageSamosa Chaat Recipe BBC Good FoodSheenaNo ratings yet

- Black and Decker TRO480SS OvenDocument21 pagesBlack and Decker TRO480SS OvenMildret GaleanoNo ratings yet

- Cookery & Larder Theory-I - 21.11.2016Document1 pageCookery & Larder Theory-I - 21.11.2016Kumar SatyamNo ratings yet

- 7 Penanganan Limbah BuahDocument24 pages7 Penanganan Limbah BuahAlgi RiveraNo ratings yet

- The Dukan Diet Made Easy by Pierre Dukan - ExcerptDocument12 pagesThe Dukan Diet Made Easy by Pierre Dukan - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group100% (4)

- HM 102Document260 pagesHM 102Barnali DuttaNo ratings yet

- Personal Best A2 Elm TeacherDocument196 pagesPersonal Best A2 Elm TeacherNgọc Tú NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Vegetarianism: 1. Eating HabitsDocument2 pagesVegetarianism: 1. Eating HabitsWeronika Kujawa-PawlakNo ratings yet

- Lillianwills Csec Foodnuthealth Plansheet 2Document5 pagesLillianwills Csec Foodnuthealth Plansheet 2api-588263485No ratings yet

- Learning Outcome 1:: Prepare Stocks For Required Menu ItemsDocument72 pagesLearning Outcome 1:: Prepare Stocks For Required Menu ItemsMarieta Bandiala100% (4)

- Dr. HussinDocument2 pagesDr. HussinSaravanan RamanNo ratings yet

- Adapted From Sarap Pinoy: Pichi Pichi IngredientsDocument7 pagesAdapted From Sarap Pinoy: Pichi Pichi Ingredientsvague_darklordNo ratings yet

- IIFYM Recipe EbookDocument68 pagesIIFYM Recipe Ebookaustinvanscoy100% (1)

- Which Greens Are Better Raw VsDocument25 pagesWhich Greens Are Better Raw VsSerena LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Proposal SamsWok CateringDocument11 pagesProposal SamsWok CateringvioNo ratings yet