Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MC m6 Cancer+ovario+precoz

Uploaded by

Grecia Castro COriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MC m6 Cancer+ovario+precoz

Uploaded by

Grecia Castro CCopyright:

Available Formats

2202

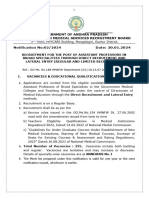

Prognostic Factors for High-Risk Early-Stage

Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study

John K. Chan, MD1

Chunqiao Tian, MS2

Bradley J. Monk, MD3

Thomas Herzog, MD4

Daniel S. Kapp, MD, PhD5

Jeffrey Bell, MD6

Robert C. Young, MD7

BACKGROUND. The purpose was to identify the factors predictive of recurrence

and survival in patients with high-risk (stage I, grade 3; stage IC, stage II, or clear

cell) epithelial ovarian cancer after adjuvant therapy.

METHODS. Data was extracted from patients who underwent primary surgery followed by adjuvant therapy in 2 randomized trials by the Gynecologic Oncology

Group (Protocols 95 and 157). Kaplan-Meier survival estimates and Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for covariates were used for analyses.

RESULTS. Of 506 patients (median age 5 56.2 years), 347 (68.6%) had stage I and

1

Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and

Reproductive Sciences, University of California,

San Francisco School of Medicine, UCSF Helen

Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, San

Francisco, California.

2

GOG Statistical & Data Center, Roswell Park

Cancer Institute, Buffalo, New York.

3

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chao

Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University

of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange,

California.

4

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University, New York, New York.

5

Department of Radiation Oncology, Stanford

University School of Medicine, Stanford Cancer

Center, Stanford, California.

6

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ohio

State University, Riverside Methodist Hospital,

Columbus, Ohio.

7

Department of Medical Oncology, Fox Chase

Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

This study was supported by National Cancer

Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology

Group Administrative Office (CA27469), the

Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data

Center (CA37517), and Gynecologic Oncology

Group new investigator award to JKC.

The following Gynecologic Oncology Group

member institutions participated in this study:

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Oregon

Health Sciences University, Duke University

Medical Center, Abington Memorial Hospital,

University of Rochester Medical Center, Walter

Reed Army Medical Center, Wayne State

University, University of Minnesota Medical

2008 American Cancer Society

159 (31.4%) had stage II cancers. The 5-year recurrence-free (RFS) and overall survivals (OS) were 75.5% and 81.7%, respectively. On multivariate analysis, older age,

higher stage, higher grade, and malignant cytology were independent prognostic

factors predictive for recurrence and poorer survival. The risk of recurrence was

higher for those !60 versus < 60 years (hazards ratio [HR] 5 1.57, 95% confidence

interval [CI], 1.122.19), stage II (stage II: HR 5 2.70, 95% CI, 1.415.16) versus

stage IA or IB, grade 2 (HR 5 1.84, 95% CI, 1.043.27) and grade 3 (HR 5 2.47, 95%

CI, 1.394.37) versus grade 1, and positive versus negative cytology (HR 5 1.72,

95% CI, 1.212.45). By using these factors in a prognostic index, those with lowrisk (no or 1 risk factor), intermediate-risk (2 factors), and high-risk (34 risk factors) disease had survivals of 88%, 82%, and 75%, respectively (P < .05).

CONCLUSIONS. Age, stage, grade, and cytology are important prognostic factors in highrisk early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer. This information may be used in the design

of future clinical trials. Cancer 2008;112:220210. ! 2008 American Cancer Society.

KEYWORDS: ovarian cancer, early-stage, prognosis, survival.

School, University of Southern California at Los

Angeles, University of Mississippi Medical Center,

Colorado Gynecologic Oncology Group P.C.,

University of California at Los Angeles, University

of Pennsylvania Cancer Center, University of

Miami School of Medicine, Milton S. Hershey

Medical Center, Georgetown University Hospital,

University of Cincinnati, University of North

Carolina School of Medicine, University of Iowa

Hospitals and Clinics, University of Texas

Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Indiana

University School of Medicine, Wake Forest

University School of Medicine, Albany Medical

College, University of California Medical Center at

Irvine, Tufts-New England Medical Center, RushPresbyterian-St. Lukes Medical Center, SUNY

Downstate Medical Center, University of

Kentucky, Eastern Virginia Medical School, The

Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Johns Hopkins

Oncology Center, State University of New York at

Stony Brook, Eastern Pennsylvania GYN/ONC

DOI 10.1002/cncr.23390

Published online 17 March 2008 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

Center, P.C., Southwestern Oncology Group,

Washington University School of Medicine,

Cooper Hospital/University Medical Center,

Columbus Cancer Council, North Central

Cancer Treatment Group, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Fox Chase Cancer

Center, Medical University of South Carolina,

Womens Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma,

University of Chicago, and Tacoma General

Hospital.

Address for reprints: John K. Chan, MD, Department

of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences,

University of California, San Francisco School of

Medicine, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive

Cancer Center, 1600 Divisadero St., Box 1702, San

Francisco, CA 94143-1702; Fax: 415-885-3586;

E-mail: chanjohn@ obgyn.ucsf.edu

Received September 25, 2007; revision received

November 9, 2007; accepted November 19, 2007.

Stage I-II Prognostic Factors/Chan et al.

n 2006 there will be an estimated 20,180 new

epithelial ovarian cancers diagnosed in the US,

with approximately one-third having FIGO (International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology) stage

I and II disease.1 Although the survival of early-stage

disease is significantly higher than those with advanced cancers, approximately 20% to 30% of these

patients will die of their disease.27

The clinical and pathologic prognostic factors

that have been previously described for patients with

early-stage epithelial ovarian cancers include: age,

stage, tumor rupture, cell type, tumor grade, large

volume ascites, and dense adhesions.816 The limitations of many of these prior studies include the small

sample size, inadequacy of surgical staging, inclusion

of borderline tumors, stage III cancers with minimal

residual disease, lack of central pathology review,

and variation in adjuvant therapies.

Young et al.10 suggested that women with lowrisk cancers, defined as stage IA, IB, grade 1 or 2,

nonclear-cell histologies, do not need further adjuvant therapy. Patients with high-risk early-stage

epithelial ovarian cancer, defined as stage I, grade 3;

stage IC, stage II, and clear-cell cancers, were felt to

require postsurgical adjuvant treatment. Over the

past 20 years, the Gynecologic Oncology Group

(GOG) has conducted 2 large prospective clinical

trials on this population. Because both clinical trials

had the same eligibility criteria for patient entry,

these studies provide a unique opportunity to investigate the prognostic factors for high-risk early-stage

ovarian cancer. The results of this analysis can

potentially allow us to assess factors that are predictive for recurrence and survival in these women.

More important, it can help identify subgroups at

significant risk for recurrence after chemotherapy

treatments who may warrant novel therapies and

more aggressive treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In all, 506 women diagnosed with high-risk early-stage

epithelial ovarian cancer patients enrolled in 2 prospective randomized clinical trials conducted by

the GOG, protocol 95 (n 5 205) and protocol 157

(n 5 301). High-risk early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer was defined as stage IA or IB (grade 3), stage IC or

II (any grade), and stage I or II clear-cell epithelial

ovarian cancer. Of these, 150 patients with incomplete

staging information were excluded from this analysis.

Patients provided written informed consent consistent

with all federal, state, and local requirements before

enrolling in the protocols. Details regarding eligibility

criteria, treatment, and outcome for each particular

study have been previously published.17,19 On the

2203

basis of the study entry criteria, a complete surgical

staging procedure was required. In summary, all peritoneal surfaces, including the undersurfaces of both

diaphragms, serosa, and mesentery, were to be visually

inspected and palpated for evidence of implants. If

there was no evidence of disease beyond the ovary or

pelvis, biopsies of the cul-de-sac, vesico uterine peritoneum, bilateral pelvic side walls, paracolic gutters, and

undersurface of the diaphragm, and sampling of the

pelvic and para-aortic nodes, were to be performed.

All patients who underwent surgical staging were operated on by gynecologic oncologists mostly from academic institutions. In addition, all tumors underwent

central pathology review by expert gynecologic oncology pathologists.

Baseline performance status before initiating

chemotherapy was defined according to GOG criteria

as: 0 5 normal activity; 1 5 symptomatic, fully ambulatory; 2 5 symptomatic, in bed less than 50% of

the time. The primary endpoints for both studies

were disease recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS). RFS was calculated from the date of

study enrollment to the date of disease recurrence

(confirmed on physical, serologic, or radiologic exam),

or most recent follow-up visit. OS was calculated

from the date of study enrollment to the date of

death regardless of cause or last follow-up.

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed

initially to estimate RFS and OS by each variable, using

a log-rank test to compare the differences in survival

functions. Multivariate analysis was then conducted to

identify the independent prognostic factors as well as

to estimate their effects on RFS and OS adjusted for

covariates. In survival analysis, patients with a GOG

performance status of 1 or 2 were combined because

of comparable associations with prognosis. In addition,

those with suspicious positive washings were considered positive for cytology. Furthermore, stage I patients

were further divided into 2 subgroups (stage IA/IB and

stage IC). We elected to use a categorical variable for

age, defined as < 60 years versus !60 years old based

on preassessment. Multivariate analysis was conducted

using a stepwise Cox proportional hazards model, stratified by type of treatment to control for potential confounding effects of the 2 study protocols and type of

treatment. All statistical tests were 2-tailed with a significance level set at 5%. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) v. 9.1

(SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 506 patients included in this analysis, the median age at diagnosis was 56 years (range, 2288

2204

CANCER

May 15, 2008 / Volume 112 / Number 10

TABLE 1

Patient and Clinicopathologic Characteristics (N 5 506)

Age, y

< 50

5059

6069

!70

Median [range]

Race

White

Black

Hispanic

Other

Performance status

0

1

2

FIGO stage

IA

IB

IC

IIA

IIB

IIC

Histology

Serous

Endometrioid

Clear cell

Mucinous

Other

Tumor grade*

1

2

3

Not graded, clear cell

Presence of Ascites

Yes

No

Cytology

Positive

Suspicious

Negative

Unknown

Ruptured tumor

Yes

No

Treatmenty

Protocol 95 32P

Protocol 95 CP

Protocol 157 PC (3)

Protocol 157 PC (6)

No. of patients

152

146

123

85

56

30.0

28.6

24.3

16.8

[2588]

451

20

21

14

89.1

4.0

4.2

2.8

264

222

20

52.2

43.9

4.0

69

10

268

43

28

88

13.6

2.0

53.0

8.5

5.5

17.4

108

134

137

50

77

21.3

26.5

27.1

9.9

15.2

95

127

147

137

18.8

25.1

29.1

27.1

153

353

30.2

69.8

125

23

340

12

25.0

4.6

68.0

2.4

219

287

43.3

56.7

98

107

155

146

19.4

21.1

30.6

28.9

* Clear cell not graded.

y 32

P indicates intraperritoneal phosphate; CP, cyclophosphamide 1 cisplatin; PC (3), paclitaxel 1

carboplatin for 3 courses; PC (6), paclitaxel 1 carboplatin for 6 courses.

years) (Table 1). The majority (89.1%) of these

patients were white and the remainder were characterized as Black (4%), Hispanic (4.2%), and Others

(2.8%). The baseline GOG performance status of

these women was 0, 1, and 2 in 52.2%, 43.9%, and

4.0%, respectively. All women underwent primary

surgery based on GOG standards. In all, 347 (68.6%)

patients had stage I disease, with stage IA in 13.6%,

IB in 2.0%, and 1C in 53.0%; 159 (31.4%) had stage II

cancers with stage IIA in 8.5%, IIB in 5.5%, and IIC

in 17.4%. Histologic cell types were distributed as

follows: clear cell (27.1%), endometrioid (26.5%),

serous (21.3%), mucinous (9.9%), and other cell types

(15.2%). Tumor grades were distributed as: grade 1

(18.8%), grade 2 (25.1%), grade 3 (29.1%), and not

graded (for clear cell) (27.1%). Of all patients, 153

(30.2%) were found to have ascites, and 219 (43.3%)

had tumor rupture found on surgery. On final pathology review of all washings and ascites, 148 (29.6%)

were cytologically positive (n 5 125) or suspicious

positive (n 5 23). The presence of ascites during surgery was greater in stage IC (33.6%) and stage II

(32.7%) compared with stage IA/IB (13.9%). The presence of ascites was also associated with positive

cytology: 46.4% of patients with malignant cells cytologically had ascites and 21.8% of patients without

ascites had positive cytology. Furthermore, most

patients with stage IC (61.9%) or mucinous (62.0%)

tumors had tumor rupture at the time of surgery.

Stage of disease was associated with tumor histology

and grade. Patients with mucinous or clear-cell

histologies were more likely to have stage I rather

than stage II disease compared with other histologies

(81.0% for clear cell, 94.0% for mucinous vs 67.7%

for other histologies). Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for RFS and OS are demonstrated in

Table 2.

All of the patients on these 2 trials (GOG 157 and

95) were treated with adjuvant platinum-based

chemotherapy or intraperitoneal radioactive chromic

phosphate. Nineteen percent of patients were treated

with intraperitoneal phosphate (32P), 21% with cyclophosphamide/cisplatin (CP), 31% with carboplatin/

paclitaxel (PC) for 3 courses, and 29% with carboplatin/paclitaxel for 6 courses.

With a median follow-up of 98 months (136

months for protocol 95 and 92 months for protocol

157), 140 recurrences (28%) and 151 (30%) deaths

were observed. The estimates of RFS and OS by

patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. Overall,

5-year RFS and OS were predicted to be 76% and

82%, respectively. Patients with age !60 years, stage

II, tumor grade 2 or 3, with the presence of ascites or

positive cytology had significantly worse RFS. There

Stage I-II Prognostic Factors/Chan et al.

TABLE 2

Recurrence-free Survival (RFS) and Overall Survival (OS) by Patient

Characteristics (N 5 506)

RFS

No. of

patients

Age group, y

< 60

!60

Race

White

Other

GOG performance

0

1 or 2

Stage

IA or IB

IC

II

Histology

Serous

Endometrioid

Clear cell

Mucinous

Others

Tumor grade*

1

2

3

Not graded, clear cell

Ascites

Yes

No

Cytologyy

Positive

Negative

Ruptured tumor

Yes

No

Type of treatment{

32

P

CP

PC(3)

PC(6)

% 5-year

RFS

% 5-year

OS

Disease recurrence

80.1

68.5

.004

84.8

77.1

<.001

451

55

74.9

80.9

.29

82.6

73.7

.96

264

242

76.4

74.2

.47

81.7

81.6

.24

87.1

77.8

65.9

.001

108

134

137

50

77

66.4

75.6

79.6

85.9

73.9

.16

95

127

147

137

85.1

73.4

67.4.

79.6

153

353

85.9

83.7

76.2

Death

HR

95% CI

HR

95% CI

1.0

1.57

1.122.19

.009

1.0

1.96

1.412.71

<.001

1.0

1.74

2.70

0.913.33

1.415.16

.003

1.0

1.54

2.36

0.852.79

1.304.27

.005

1.0

1.84

2.47

1.66

1.043.27

1.394.37

0.913.04

.02

1.0

1.23

1.86

1.46

0.722.09

1.103.15

0.852.50

.09

1.0

1.72

1.212.45

.003

1.0

1.53

1.092.16

.02

302

204

79

268

159

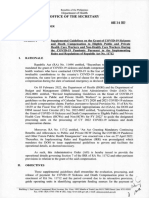

TABLE 3

Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors for Recurrence-free

Survival (RFS) and Overall Survival (OS) (N 5 506)

OS

2205

.009

79.3

83.7

81.5

83.7

80.5

.47

.01

85.9

81.6

79.2

81.5

.10

71.4

77.3

.05

81.3

81.9

.58

148

358

67.0

78.9

<.001

75.5

84.2

.01

219

287

76.8

74.5

.22

83.1

80.6

.59

98

107

155

146

66.8

77.2

76.3

79.2

.08

77.3

84.0

80.3

84.5

.44

Age, y

< 60

!60

Stage

IA or IB

IC

II

Tumor grade*

1

2

3

Not graded, clear cell

Cytology

Negative

Positive

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

* Hazard ratio estimated by Cox model adjusted for age group, stage, tumor grade, and cytology, as

well as stratified with type of treatment.

GOG indicates Gynecologic Oncology Group.

* Clear cell not graded.

y

Suspicious positive (n 5 23) classified as positive and unknown classified as negative.

{ 32

P indicates intraperitoneal phosphate; CP, cyclophosphamide 1 cisplatin; PC(3), paclitaxel 1 carboplatin for 3 cycles; PC(6), paclitaxel 1 carboplatin for 6 cycles. Median survival time was estimated

by Kaplan-Meier procedure and a log-rank test was used to compare survival functions.

is also a suggestion that patients treated by PC and

CP had comparable RFS, but both of them had

improved RFS compared with patients treated by 32P.

Multivariate analysis identified 4 factors (age,

stage, tumor grade, and cytology) independently predictive of disease recurrence (Table 3). The relative

risk of disease recurrence for patients at age !60

years versus age < 60 years was 1.57 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.122.19). The risk for recurrence was increased with advanced stage of disease

(stage II: hazard ratio [HR] 5 2.70, 95% CI, 1.415.16,

relative to stage IA or IB). In addition, patients with

grade 2 (HR 5 1.84, 95% CI, 1.043.27) and grade 3

(HR 5 2.47, 95% CI, 1.394.37) tumors were at

increased risk for disease recurrence compared with

grade 1 cancers. Women with positive cytology had a

significantly elevated risk for disease recurrence compared with those with negative cytology (HR 5 1.72,

95% CI, 1.212.45). Because the clear-cell patients

were not graded and all stage IA or IB patients

selected had grade 3 tumors, the results on tumor

grade above may not well reflect the effect of tumor

grade on prognosis. Further analysis restricted to

stage IC, stage II, excluding clear-cell patients was

conducted. The 5-year RFS was estimated to be

85.1%, 73.4%, and 62.6% for grade 1, grade 2, and

grade 3, respectively. The adjusted HR was 1.89 (95%

CI, 1.063.35) for grade 2 and 2.55 (95% CI, 1.42

4.59) for grade 3 compared with tumor grade 1, confirming the significance of tumor grade on disease

recurrence. All other variables (race, performance

status, histology, tumor rupture, and ascites) were

not significantly associated with RFS. The results on

OS were similar. These findings were consistent in

the OS analyses.

Figures 1 to 4 demonstrate the Kaplan-Meier

estimate of RFS and OS by age group, stage of dis-

2206

CANCER

May 15, 2008 / Volume 112 / Number 10

FIGURE 1. (A) Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival by age group

(P 5 .004). (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival by age group (P < .001).

ease, tumor grade, and cytology. Among the prognostic parameters, these independent prognostic factors

were used to develop a prognostic index for potential

clinical application. The prognostic model for RFS is

based on the 4 risk factors: age !60 years (vs

age < 60 years), stage II disease (vs stage I disease),

positive cytology (vs negative cytology), and grade 2

3 tumors or clear cell (vs grade 1 disease). Low-risk

patients were defined as those with no or 1 risk factor; intermediate-risk patients as those with any 2

risk factors; and high-risk patients as women with

any 3 or 4 risk factors. The 5-year RFS of the low-,

intermediate-, and high-risk groups was estimated to

be 88%, 71%, and 62%, respectively. On the basis of

the number of risk factors, patients in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups had corresponding

OSs of 88%, 82%, and 75% (P < .05) (Fig. 5A,B).

DISCUSSION

Early-stage ovarian cancer patients constitute a heterogeneous group with respect to risk of recurrence

and survival. Prior reports have shown that patients

with early-stage disease have overall survivals ran-

FIGURE 2. (A) Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival by stage (P 5 .001).

(B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival by stage (P 5 .009).

ging from 60% to 100%.1,2,46,20 Thus, stratifying this

heterogeneous group of patients can potentially

identify subgroups of high-risk patients for individualized novel therapies in an attempt to improve

outcome. Likewise, it is important to identify a lowrisk group that may not require further cytotoxic

treatment. In this current analysis of 506 women

diagnosed with high-risk stage I and II epithelial

ovarian cancer treated on 2 GOG prospective randomized trials, we found that older age, higher stage,

higher grade, and positive cytology are important

prognostic factors for recurrence and survival.

Earlier studies on the prognostic significance of

age in ovarian cancer have been inconclusive.

Although most reports have shown that younger

women are diagnosed with lower-stage and more

well-differentiated tumors, and have an improved

outcome compared with older women,2125 others

have found that age is not an independent prognostic factor after adjusting for stage and grade of disease.2628 In addition, because of the low prevalence

of young patients diagnosed with invasive ovarian

cancer, these studies have also been limited by small

numbers of patients, inclusion of low malignant

Stage I-II Prognostic Factors/Chan et al.

2207

FIGURE 3. (A) Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival by grade of disease

FIGURE 4. (A) Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival by cytology

(P 5 .004). (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival by grade of disease (P 5 .01).

(P < .001). (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival by cytology (P 5 .01).

potential tumors, germ cell or sex cord stromal

tumors, and unstaged cancers. In a recent analysis of

28,165 patients, Chan et al.28 identified 400 women

who were < 30 years (very young) (1.4%), 11,601

were 30 to 60 (young) (41.2%), and 16,164 were > 60

(older) (57.4%) years of age. Across all stages, very

young women had a significant survival advantage

over the young and older groups, with 5-year disease-specific survival estimates at 78.7% versus

58.8% and 35.3%, respectively (P < .001). In this current analysis of a well-characterized group of earlystage ovarian cancer patients with long follow-up,

younger age was an independent prognostic factor

for improved survival after controlling for surgery,

stage, grade, adjuvant therapy, and other clinicopathologic factors.

Previous studies have also demonstrated that

stage of disease is a prognostic factor in early-stage

ovarian cancers.13,16,2933 Patients in this current

study with stage I cancers have a 5-year disease-specific survival of 84% compared with 76% in those

with stage II disease. An analysis on the subgroups

of stage I cancers found that those with stage IA or

IB disease have a survival of 85.9%. Given the excel-

lent outcome of these patients and the potential

toxicities associated with adjuvant chemotherapy,17,18

future studies must be carefully structured to determine the risk and benefit of cytotoxic chemotherapy

in low-risk disease. However, the outcome for

patients with stage II is significantly poorer, with RFS

and OS of 65.9 and 76.2%, respectively. Prior studies

have included these patients in clinical trials along

with more advanced (stage III and IV) cancers.31,34

Although the survival of stage II patients is poorer

compared with stage I disease, these women still

have a distinct survival advantage over those with

more advanced cancers.

Tumor grade was also found to be an independent prognostic factor for progression-free and disease-specific survival in our study. Similarly, Vergote

et al.35 studied a group of 1545 patients with stage I

disease and found that grade of disease was an independent prognostic factor associated with diseasefree survival. These findings have also been confirmed by other, smaller studies.11,14,16,30,3644

In this current analysis, malignant cytology was

an independent prognostic factor for increased risk

of recurrence and poorer survival. Early studies have

2208

CANCER

May 15, 2008 / Volume 112 / Number 10

FIGURE 5. (A) Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival by number of risk

factors (age !60 years, stage II disease, positive cytology, and grade 2"3

tumors or clear cell). Low-risk: 0"1 risk factors; mid-risk: 2 risk factors;

high-risk: 3"4 risk factors (P < .001). (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival by

number of risk factors (P < .001).

demonstrated that patients with positive washing have

a poorer prognosis.45,46 Creasman and Rutledge47

reported that 60% of 98 patients with ovarian cancer

who underwent surgery had abnormal peritoneal

cytologic specimens. Likewise, a more recent report

also found positive peritoneal washing cytology at

initial surgery in 90 (80.4%) of 112 patients with

ovarian carcinomas.48 Those authors also showed

that positive cytology portends a poorer prognosis.

The prognostic significance of clear-cell histology

compared with other subtypes of epithelial ovarian

cancers remains controversial. In a recent review of

54 studies on ovarian clear-cell carcinoma, Pectasides et al.49 showed that clear-cell cancers have a

significantly poorer survival compared with other

histologic subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. In

patients with more advanced stage cancer, the

response rate to platinum-based chemotherapy and

survival were significantly lower than those with serous tumors. However, others have not been able to

find an association between cell type and prognosis

in early-stage disease. Contributing factors for these

conflicting results may include the lack of central

pathology review and intraobserver variabilities on

determining cell type50,51 and various treatment regimens.49 In this current study of early-stage ovarian

cancer where the majority of patients were uniformly

staged and treated on 2 standardized protocols, we

were unable find a statistically significant survival

difference between clear-cell and other histologies.

Consistent with prior reports, our data did not

reveal that tumor rupture was associated with a

poorer outcome.15,30,39 However, Vergote et al.35

found a deleterious effect of rupture either during or

before surgery on disease-free survival. The interaction between tumor rupture and more early-stage

cancers in our study may have influenced our ability

to determine the true significance of tumor rupture.

One of the shortcomings of our study is that there is

a lack of information regarding the time of rupture,

eg, preoperatively or intraoperatively. Some prior studies have found that preoperative rupture may carry

a worse prognosis compared with intraoperative rupture.14,52 In addition, this current analysis did not

find ascites to be a significant prognostic factor. This

may be explained by the interaction between ascites,

cytology, and stage of disease. For, after adjusting for

these factors, ascites was no longer prognostically

important.

Our study was limited by the potential selection

bias inherent in randomized trials. This study cohort

may comprise a subset of high-risk patients treated

at research centers that may not represent the experience in the general population. Furthermore, given

that these patients were enrolled in these 2 large

trials ranging from 1986 to 1998, there may exist significant differences related to cancer supportive care

and treatment of recurrences over this time period.

Moreover, there was a lack of complete information

regarding the extent of the comprehensive staging

procedures on all patients. In fact, 29.5% of patients

in the GOG 157 trial had incomplete or inadequately

documented surgical staging information.17 It is important to note that the descriptive statistics and

results of this study were based on a selected group

of patients with high-risk early-stage cancers defined

by the eligibility criteria from 2 randomized clinical

trials of the GOG. Thus, in this specific subset of

patients there is a significantly higher proportion

(27.1%) of clear-cell histologies compared with other

cell types. Therefore, these results may not apply to

the overall group of stage I and II patients, particularly those with stage I, grade 1 or 2 disease, and

nonclear-cell type. Although it is important to iden-

Stage I-II Prognostic Factors/Chan et al.

tify a low-risk group that may not require further

cytotoxic treatment, we are unable to define such a

low-risk group of patients from this report because

all of the women in these clinical trials received adjuvant therapy. Thus, a prospective trial designed to

analyze the benefits of adjuvant therapy versus observation is warranted in this low-risk group defined

by this current study.

The strengths of our study include the high

number of patients reported from 2 randomized prospective trials with defined selection criteria and over

80 months of follow-up. Furthermore, these patients

underwent staging by gynecologic oncologists mostly

from academic institutions. In addition, these tumors

underwent central pathology review by expert gynecologic oncology pathologists.

In summary, our findings suggest that age, stage,

grade, and malignant cytology are important prognostic factors in early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer.

This information may be considered in the design of

future clinical trials.

REFERENCES

1.

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA

Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106130.

2. Partridge EE, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer

Data Base report on ovarian cancer treatment in United

States hospitals. Cancer. 1996;78:22362246.

3. Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD, Manji M, et al. Moderate-risk

ovarian cancer (stage I, grade 2; stage II, grade 1 or 2) treated with cisplatin chemotherapy (single agent or combination) and pelvi-abdominal irradiation. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

1994;4:272278.

4. Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of

the ovary. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(Suppl 1):135166.

5. Averette HE, Janicek MF, Menck HR. The National Cancer

Data Base report on ovarian cancer. American College of

Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer

Society. Cancer. 1995;76:10961103.

6. Kosary CL. FIGO stage, histology, histologic grade, age and

race as prognostic factors in determining survival for cancers of the female gynecological system: an analysis of

197387 SEER cases of cancers of the endometrium, cervix,

ovary, vulva, and vagina. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994;10:3146.

7. Nguyen HN, Averette HE, Hoskins W, et al. National survey

of ovarian carcinoma. VI. Critical assessment of current

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system. Cancer. 1993;72:30073011.

8. Dembo AJ, Davy M, Stenwig AE, et al. Prognostic factors in

patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:263273.

9. Sevelda P, Vavra N, Schemper M, et al. Prognostic factors

for survival in stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer.

1990;65:23492352.

10. Young RC, Walton LA, Ellenberg SS, et al. Adjuvant therapy

in stage I and stage II epithelial ovarian cancer. Results of

2 prospective randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:

1021107.

2209

11. Finn CB, Luesley DM, Buxton EJ, et al. Is stage I epithelial

ovarian cancer overtreated both surgically and systemically? Results of a 5-year cancer registry review. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol. 1992;99:5458.

12. Vergote IB, Kaern J, Abeler VM, et al. Analysis of prognostic

factors in stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma: importance

of degree of differentiation and deoxyribonucleic acid ploidy

in predicting relapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:4052.

13. Bertelsen K, Holund B, Andersen JE, et al. Prognostic factors and adjuvant treatment in early epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1993;3:211218.

14. Sjovall K, Nilsson B, Einhorn N. Different types of rupture

of the tumor capsule and the impact on survival in early

ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1994;4:333336.

15. Ahmed FY, Wiltshaw E, AHern RP, et al. Natural history

and prognosis of untreated stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:29682975.

16. Trope C, Kaern J, Hogberg T, et al. Randomized study on

adjuvant chemotherapy in stage I high-risk ovarian cancer

with evaluation of DNA-ploidy as prognostic instrument.

Ann Oncol. 2000;11:281288.

17. Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, et al. Randomized phase III

trial of 3 versus 6 cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:432439.

18. Travis LB, Holowaty EJ, Bergfeldt K, et al. Risk of leukemia

after platinum-based chemotherapy for ovarian cancer.

N Engl J Med. 1999;340:351357.

19. Young RC, Brady MF, Nieberg RK, et al. Adjuvant treatment

for early ovarian cancer: a randomized phase III trial of

intraperitoneal 32P or intravenous cyclophosphamide and

cisplatina gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin

Oncol. 2003;21:43504355.

20. Nguyen HN, Averette HE, Hoskins W, et al. National survey

of ovarian carcinoma. Part V. The impact of physicians

specialty on patients survival. Cancer. 1993;72:36633670.

21. Chan JK, Loizzi V, Lin YG, et al. Stages III and IV invasive

epithelial ovarian carcinoma in younger versus older

women: what prognostic factors are important? Obstet

Gynecol. 2003;102:156161.

22. Plaxe SC, Braly PS, Freddo JL, et al. Profiles of women age

3039 and age less than 30 with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:651654.

23. Rodriguez M, Nguyen HN, Averette HE, et al. National survey of ovarian carcinoma XII. Epithelial ovarian malignancies in women less than or equal to 25 years of age.

Cancer. 1994;73:12451250.

24. Smedley H, Sikora K. Age as a prognostic factor in epithelial

ovarian carcinoma. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92:839842.

25. Thigpen T, Brady MF, Omura GA, et al. Age as a prognostic

factor in ovarian carcinoma. The Gynecologic Oncology

Group experience. Cancer. 1993;71:606614.

26. Duska LR, Chang YC, Flynn CE, et al. Epithelial ovarian

carcinoma in the reproductive age group. Cancer. 1999;

85:2623269.

27. Massi D, Susini T, Savino L, et al. Epithelial ovarian tumors

in the reproductive age group: age is not an independent

prognostic factor. Cancer. 1996;77:1131116.

28. Chan JK, Urban R, Cheung MK, et al. Ovarian cancer in

younger vs older women: a population-based analysis. Br J

Cancer. 2006;95:13141320.

29. Nagele F, Petru E, Medl M, et al. Preoperative CA 125: an

independent prognostic factor in patients with stage I

epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:259264.

2210

CANCER

May 15, 2008 / Volume 112 / Number 10

30. Brugghe J, Baak JP, Wiltshaw E, et al. Quantitative prognostic features in FIGO I ovarian cancer patients without postoperative treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;68:4753.

31. Du Bois A, Rochon J, Lamparter C, et al. Pattern of care and

impact of participation in clinical studies on the outcome in

ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:183191.

32. Mizuno M, Kikkawa F, Shibata K, et al. Long-term prognosis of stage I ovarian carcinoma. Prognostic importance of

intraoperative rupture. Oncology. 2003;65:2936.

33. Valverde JJ, Martin M, Garcia-Asenjo JA, et al. Prognostic

value of DNA quantification in early epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:409416.

34. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy

with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer:

the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505515.

35. Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage

I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:

176182.

36. Skirnisdottir I, Seidal T, Sorbe B. A new prognostic model comprising p53, EGFR, and tumor grade in early stage epithelial

ovarian carcinoma and avoiding the problem of inaccurate

surgical staging. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:259270.

37. Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, et al. Impact of adjuvant

chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian

carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:113125.

38. Le T, Adolph A, Krepart GV, et al. The benefits of comprehensive surgical staging in the management of early-stage

epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:351

355.

39. Zanetta G, Rota S, Chiari S, et al. The accuracy of staging:

an important prognostic determinator in stage I ovarian

carcinoma. A multivariate analysis. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:

10971101.

40. Rubin SC, Wong GY, Curtin JP, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy of high-risk stage I epithelial ovarian cancer after comprehensive surgical staging. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82: 143147.

41. Villa A, Parazzini F, Acerboni S, et al. Survival and prognostic factors of early ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:

123124.

42. Bolis G, Colombo N, Pecorelli S, et al. Adjuvant treatment

for early epithelial ovarian cancer: results of 2 randomised

clinical trials comparing cisplatin to no further treatment

or chromic phosphate (32P). G.I.C.O.G.: Gruppo Interregionale Collaborativo in Ginecologia Oncologica. Ann Oncol.

1995;6:887893.

43. Sainz de la Cuesta R, Goff BA, Fuller AF Jr, et al. Prognostic

importance of intraoperative rupture of malignant ovarian

epithelial neoplasms. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:17.

44. Paramasivam S, Tripcony L, Crandon A, et al. Prognostic

importance of preoperative CA-125 in International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage I epithelial

ovarian cancer: an Australian multicenter study. J Clin

Oncol. 2005;23:59385942.

45. Keettel WC, Pixley E. Diagnostic value of peritoneal washings. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1958;1:592606.

46. Morton DG, Moore JG, Chang N. The clinical value of peritoneal lavage for cytologic examination. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;81:11151125.

47. Creasman WT, Rutledge F. The prognostic value of peritoneal cytology in gynecologic malignant disease. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110:773781.

48. Zuna RE, Behrens A. Peritoneal washing cytology in gynecologic cancers: long-term follow-up of 355 patients. J Natl

Cancer Inst. 1996;88:980987.

49. Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Psyrri A, et al. Treatment issues

in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a different entity?

Oncologist. 2006;11:10891094.

50. Baak JP, Langley FA, Talerman A, et al. Interpathologist

and intrapathologist disagreement in ovarian tumor

grading and typing. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 1986;8:354

357.

51. Hernandez E, Bhagavan BS, Parmley TH, et al. Interobserver variability in the interpretation of epithelial ovarian

cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1984;17:117123.

52. Kodama S, Tanaka K, Tokunaga A, et al. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in patients with ovarian cancer

stage I and II. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;56:147153.

You might also like

- Management of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer: A Multidisciplinary ApproachFrom EverandManagement of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer: A Multidisciplinary ApproachJose G. GuillemNo ratings yet

- Management of Paget Disease of The Breast With RadiotherapyDocument8 pagesManagement of Paget Disease of The Breast With RadiotherapyAndreas RonaldNo ratings yet

- 10.1186@s13048 020 00619 6Document10 pages10.1186@s13048 020 00619 6Berry BancinNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Breast Cancer Subtypes in Two Prospective Cohort Studies of Breast Cancer SurvivorsDocument13 pagesEpidemiology of Breast Cancer Subtypes in Two Prospective Cohort Studies of Breast Cancer SurvivorsZawali DzArticlesNo ratings yet

- Sun 等。 - 2018 - Age-dependent difference in impact of fertility pr的副本Document10 pagesSun 等。 - 2018 - Age-dependent difference in impact of fertility pr的副本Jing WangNo ratings yet

- Cummings Et Al-2014-The Journal of PathologyDocument9 pagesCummings Et Al-2014-The Journal of Pathologyalicia1990No ratings yet

- Poorer Survival Outcomes For Male Breast Cancer Compared With Female Breast Cancer May Be Attributable To In-Stage MigrationDocument9 pagesPoorer Survival Outcomes For Male Breast Cancer Compared With Female Breast Cancer May Be Attributable To In-Stage MigrationabcdshNo ratings yet

- Wenzel 2005Document8 pagesWenzel 2005cikox21848No ratings yet

- Determinants of Long-Term Survival Decades After Esophagectomy For Esophageal CancerDocument38 pagesDeterminants of Long-Term Survival Decades After Esophagectomy For Esophageal CancerJoão Gabriel Oliveira de SouzaNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofJoão AugustoNo ratings yet

- Medicine American Journal of Hospice and PalliativeDocument6 pagesMedicine American Journal of Hospice and Palliativem1k0eNo ratings yet

- Adjuvant Chemotherapy Is Not Associated With A Survival Benefit ForDocument6 pagesAdjuvant Chemotherapy Is Not Associated With A Survival Benefit ForHerry SasukeNo ratings yet

- ArticleText 78614 1 10 20191030Document7 pagesArticleText 78614 1 10 20191030Melody CyyNo ratings yet

- OvarianDocument14 pagesOvarianherryNo ratings yet

- Le 2005Document6 pagesLe 2005Waode RadmilaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Pathologic Spread Patterns of Endometrial Cancer: A Group StudyDocument7 pagesSurgical Pathologic Spread Patterns of Endometrial Cancer: A Group StudyInsighte Behavioral CareNo ratings yet

- (14796821 - Endocrine-Related Cancer) Time-Varying Effects of Prognostic Factors Associated With Long-Term Survival in Breast CancerDocument13 pages(14796821 - Endocrine-Related Cancer) Time-Varying Effects of Prognostic Factors Associated With Long-Term Survival in Breast CancerKami KamiNo ratings yet

- Cancer Volume 77 Issue 2 1996Document7 pagesCancer Volume 77 Issue 2 1996BiancaTCNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument11 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentMihaela AndreiNo ratings yet

- Total and Individual Antioxidant Intake and Risk of Epithelial Ovarian CancerDocument10 pagesTotal and Individual Antioxidant Intake and Risk of Epithelial Ovarian Cancerbonne_ameNo ratings yet

- Assisted Reproductive Technology Use and Outcomes Among Women With A History of CancerDocument7 pagesAssisted Reproductive Technology Use and Outcomes Among Women With A History of Cancertavo823No ratings yet

- Caner Gastrico en JovenesDocument13 pagesCaner Gastrico en JovenesandreaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CarisoprodolDocument9 pagesJurnal CarisoprodolTegarrachman23No ratings yet

- Feng2018 PDFDocument75 pagesFeng2018 PDFIde Yudis TiyoNo ratings yet

- Nej Me 1514353Document2 pagesNej Me 1514353anggiNo ratings yet

- Bristow 2002Document12 pagesBristow 2002Lưu Chính HữuNo ratings yet

- HealthLinx Limited PaperDocument10 pagesHealthLinx Limited PapermaikagmNo ratings yet

- 43 FullDocument9 pages43 Fullnayeta levi syahdanaNo ratings yet

- 12 2002 Patterns of Multiple Recurrences of SuperficialDocument9 pages12 2002 Patterns of Multiple Recurrences of SuperficialIndra T BudiantoNo ratings yet

- Annals Case Reports PDF Final Final.25.05.l22.Document13 pagesAnnals Case Reports PDF Final Final.25.05.l22.rossbar13No ratings yet

- Survival Outcomes For Different Subtypes of Epithelial Ovarian CancerDocument7 pagesSurvival Outcomes For Different Subtypes of Epithelial Ovarian CancerasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- JWH 2008 1068Document8 pagesJWH 2008 1068Khaled Loua-M'sNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument17 pagesNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptdini kusmaharaniNo ratings yet

- Metastasis Patterns and PrognoDocument17 pagesMetastasis Patterns and Prognosatria divaNo ratings yet

- Green Journal ROMADocument9 pagesGreen Journal ROMAinvestorpatentNo ratings yet

- Ogi2019 9465375Document6 pagesOgi2019 9465375Novi HermanNo ratings yet

- Objective: Breast Cancer Is The Most Common Type of Cancer Found in Women, in The United StatesDocument5 pagesObjective: Breast Cancer Is The Most Common Type of Cancer Found in Women, in The United StatesdwiNo ratings yet

- 172 - 04 101 13 PDFDocument8 pages172 - 04 101 13 PDFAlexandrosNo ratings yet

- Tumores Malignos de Anexos CutáneosDocument7 pagesTumores Malignos de Anexos CutáneostisadermaNo ratings yet

- ST Gallen 2021 A OncologyDocument20 pagesST Gallen 2021 A OncologyJorge Apolo PinzaNo ratings yet

- Tongue Cancer Pubmed VIIDocument15 pagesTongue Cancer Pubmed VIIAsri Alifa SholehahNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 855012Document16 pagesNi Hms 855012JackyHariantoNo ratings yet

- Cancer Immunology IntroductionDocument8 pagesCancer Immunology IntroductionMariana NannettiNo ratings yet

- Dok Til 1Document15 pagesDok Til 1Nurul Ulya RahimNo ratings yet

- Prognosis Node-Positive Cancer: ColonDocument3 pagesPrognosis Node-Positive Cancer: ColonEdward Arthur IskandarNo ratings yet

- Estimating The Net Survival of Patients With Gastric Cancer in Iran in A Relative Survival FrameworkDocument7 pagesEstimating The Net Survival of Patients With Gastric Cancer in Iran in A Relative Survival FrameworkRoja behnamiNo ratings yet

- Lipid Rich CarcinomaDocument4 pagesLipid Rich CarcinomaDoctorcookies MalinauNo ratings yet

- 17 Iajps17102017 PDFDocument3 pages17 Iajps17102017 PDFBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- Brazda 2010Document6 pagesBrazda 2010mod_naiveNo ratings yet

- Left Sided Breast Cancer Is Associated With Aggressive Biology and Worse Outcomes Than Right Sided Breast CancerDocument9 pagesLeft Sided Breast Cancer Is Associated With Aggressive Biology and Worse Outcomes Than Right Sided Breast CancerMSNo ratings yet

- Ovarian Cancer ThesisDocument8 pagesOvarian Cancer ThesisDon Dooley100% (1)

- Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Asian Women With Breast Cancer Receiving Anthracycline-Based Adjuvant ChemotherapyDocument6 pagesChemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Asian Women With Breast Cancer Receiving Anthracycline-Based Adjuvant ChemotherapyMirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- Daño InglesDocument9 pagesDaño InglesbrukillmannNo ratings yet

- Review: Second Consensus On Medical Treatment of Metastatic Breast CancerDocument11 pagesReview: Second Consensus On Medical Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancermohit.was.singhNo ratings yet

- David A Goldfarb Renal Transplantation 2021Document2 pagesDavid A Goldfarb Renal Transplantation 2021alan.rangel.puenteNo ratings yet

- Ijss Jan Oa08Document7 pagesIjss Jan Oa08IvanDwiKurniawanNo ratings yet

- Depressive Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life in Breast Cancer SurvivorsDocument9 pagesDepressive Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life in Breast Cancer SurvivorsCamelutza IsaiNo ratings yet

- Chimio Et Gsse ++++Document7 pagesChimio Et Gsse ++++Iman BousnaneNo ratings yet

- NeutrófiloDocument7 pagesNeutrófilolunamar21No ratings yet

- Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Patients Aged 45 Years or Younger: Outcomes and Prognostic FactorsDocument8 pagesAdvanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Patients Aged 45 Years or Younger: Outcomes and Prognostic FactorsAnnisa DiendaNo ratings yet

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocument7 pagesPolycystic Ovary SyndromeGrecia Castro CNo ratings yet

- PCO Diferential DiagnosisDocument11 pagesPCO Diferential DiagnosisGrecia Castro CNo ratings yet

- Jogc PDFDocument32 pagesJogc PDFnunki aprillitaNo ratings yet

- 4b. UrolithiasisDocument102 pages4b. UrolithiasisGrecia Castro CNo ratings yet

- Lacosamide: A Novel Antiepileptic and Anti-Nociceptive Drug On The BlockDocument5 pagesLacosamide: A Novel Antiepileptic and Anti-Nociceptive Drug On The BlockFarhatNo ratings yet

- What Kate Did at WorkDocument3 pagesWhat Kate Did at WorkSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Intervention MCQDocument2 pagesIntervention MCQmoath alseadyNo ratings yet

- K-02 (Imunologi Dasar)Document40 pagesK-02 (Imunologi Dasar)amiksalamahNo ratings yet

- Chist de Septum PellucidumDocument3 pagesChist de Septum PellucidumdansarariuNo ratings yet

- Immunological Tolerance, Pregnancy, and Preeclampsia: The Roles of Semen Microbes and The FatherDocument39 pagesImmunological Tolerance, Pregnancy, and Preeclampsia: The Roles of Semen Microbes and The FatherAnanda Yuliastri DewiNo ratings yet

- Government of Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh Medical Services Recruitment BoardDocument13 pagesGovernment of Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh Medical Services Recruitment Boardchandu93152049No ratings yet

- OligodendrogliomaDocument9 pagesOligodendrogliomaroni pahleviNo ratings yet

- Flu Specimen Collection PosterDocument1 pageFlu Specimen Collection Poster568563No ratings yet

- Elman Book FlyerDocument2 pagesElman Book FlyerCarolina CruzNo ratings yet

- Hip Interventions Project - Harris SvorinicDocument3 pagesHip Interventions Project - Harris Svorinicapi-620069244No ratings yet

- Perioperative Nursing Concept PDFDocument21 pagesPerioperative Nursing Concept PDFMari Fe100% (1)

- Skin Issue in Patient Treated With Arctic Sun Pads During Therapeutic HypothermiaDocument2 pagesSkin Issue in Patient Treated With Arctic Sun Pads During Therapeutic HypothermiamedivanceskinissuesNo ratings yet

- PSPA3714 Tutor Activities ANSWERS Chapter 6 2021Document5 pagesPSPA3714 Tutor Activities ANSWERS Chapter 6 2021Kamogelo MakhuraNo ratings yet

- Association of Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria With Sanitation of Street Vendors FoodDocument14 pagesAssociation of Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria With Sanitation of Street Vendors FoodMamta AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Cardiorespiratory Endurance and The Fitt PrincipleDocument2 pagesCardiorespiratory Endurance and The Fitt Principleapi-385952225No ratings yet

- Chapter 7-Brief Psychodynamic Therapy: BackgroundDocument54 pagesChapter 7-Brief Psychodynamic Therapy: BackgroundKarenHNo ratings yet

- Modified Early Obstetric Warning Score MEOWS MID33 AO13 v4.2Document9 pagesModified Early Obstetric Warning Score MEOWS MID33 AO13 v4.2indirinoor5No ratings yet

- Anaphylactic Death FinalDocument73 pagesAnaphylactic Death Finalkhaled eissaNo ratings yet

- Drug Education in The PhilippinesDocument32 pagesDrug Education in The PhilippinesTrixie Ann MenesesNo ratings yet

- Fs 15Document8 pagesFs 15api-299490997No ratings yet

- Awareness of Medication-Related Fall Risk A Survey of Communitydwelling Older Adults PDFDocument7 pagesAwareness of Medication-Related Fall Risk A Survey of Communitydwelling Older Adults PDFRenaldiPrimaSaputraNo ratings yet

- Jama Statin and Stroke Prevention SupplementDocument17 pagesJama Statin and Stroke Prevention SupplementMesan KoNo ratings yet

- The Nomenclature, Definition and Distinction of Types of ShockDocument14 pagesThe Nomenclature, Definition and Distinction of Types of ShockDiana AngelesNo ratings yet

- Gavage Feeding RepDocument6 pagesGavage Feeding RepEon Provido AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Ao2022 0037Document22 pagesAo2022 0037Abigael VianaNo ratings yet

- Manual Monitor Criticare Sholar IIIDocument90 pagesManual Monitor Criticare Sholar IIIandres narvaezNo ratings yet

- Invos System Improving Patient Outcomes Cerebral Somatic Oximetry BrochureDocument6 pagesInvos System Improving Patient Outcomes Cerebral Somatic Oximetry Brochuremihalcea alinNo ratings yet

- Goldberg 2012Document8 pagesGoldberg 2012Carlos Luque GNo ratings yet

- Integral University Library System Library - Iul.ac - In: New Arrival of Books: January 2019Document5 pagesIntegral University Library System Library - Iul.ac - In: New Arrival of Books: January 2019indrajit sinhaNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (27)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingFrom EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1138)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsFrom EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)