Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rheumatology 2013 Cramer Rheumatology Ket264

Uploaded by

PrissilmaTaniaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rheumatology 2013 Cramer Rheumatology Ket264

Uploaded by

PrissilmaTaniaCopyright:

Available Formats

Rheumatology Advance Access published August 9, 2013

RHEUMATOLOGY

53, 258, 268

Concise report

doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ket264

Yoga for rheumatic diseases: a systematic review

Holger Cramer1, Romy Lauche1, Jost Langhorst1 and Gustav Dobos1

Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendation for yoga as an

ancillary intervention in rheumatic diseases.

Conclusion. Based on the results of this review, only weak recommendations can be made for the

ancillary use of yoga in the management of FM syndrome, OA and RA at this point.

Key words: yoga, complementary therapies, rheumatology, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia,

carpal tunnel syndrome, review.

Introduction

Yoga is widely used by patients with a variety of rheumatic

diseases. According to the 2002 National Health Interview

Survey, patients with rheumatic diseases were 1.56 times

more likely to have practiced yoga within the last

12 months compared with the general population [1].

Deriving from ancient Indian philosophy, yoga comprises

physical exercise, relaxation and lifestyle modification [2].

In North America and Europe, yoga is most often associated with physical postures, breathing techniques and

meditation [3]. Systematic reviews have shown that yoga

seems to be a safe and effective intervention for patients

with arthritis [4] or FM [5]. However, no systematic review

has thoroughly investigated the effects of yoga on rheumatic diseases as a whole. The aim of this systematic

1

Department of Internal and Integrative Medicine, Kliniken EssenMitte, Faculty of Medicine, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen,

Germany.

Submitted 13 March 2013; revised version accepted 20 June 2013.

Correspondence to: Holger Cramer, Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Klinik fur

Naturheilkunde und Integrative Medizin, Knappschafts-Krankenhaus,

Am Deimelsberg 34a, 45276 Essen, Germany.

E-mail: h.cramer@kliniken-essen-mitte.de

review was to evaluate the quality of available evidence

and the strength of the recommendation for yoga as

a therapeutic means in the management of rheumatic

diseases.

Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [6] and the

recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration [7]

were followed.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and randomized

crossover studies were eligible. No language restrictions

were applied.

Types of participants

Patients with rheumatic diseases (e.g. RA, OA, FM, osteoporosis, gout, lupus erythematosus, Pagets disease, PsA,

Raynauds disease, reactive arthritis, bursitis, tendinitis,

CTS, tarsal tunnel syndrome, plantar fasciitis, SpA, SSc

and vasculitis) were eligible.

! The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Society for Rheumatology. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

CLINICAL

SCIENCE

Results. Eight RCTs with a total of 559 subjects were included; two RCTs had a low risk of bias. In two

RCTs on FM syndrome, there was very low evidence for effects on pain and low evidence for effects on

disability. In three RCTs on OA, there was very low evidence for effects on pain and disability. Based on

two RCTs, very low evidence was found for effects on pain in RA. No evidence for effects on pain was

found in one RCT on CTS. No RCT explicitly reported safety data.

Downloaded from http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 15, 2016

Methods. Medline/PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library and IndMED were searched through February

2013. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing yoga with control interventions in patients with

rheumatic diseases were included. Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias using the

Cochrane Back Review Group risk of bias tool. The quality of evidence and the strength of the recommendation for or against yoga were graded according to the GRADE recommendations.

Holger Cramer et al.

Types of intervention

Studies that compared yoga interventions with no treatment or any active treatment were eligible. Studies were

excluded if yoga was not the main intervention but part of

a multimodal intervention. No restrictions were made regarding yoga tradition, length, frequency or duration of the

program. Co-interventions were allowed.

Types of outcome

For inclusion, RCTs had to assess at least one primary

outcome, i.e. pain intensity orfunction. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, psychological distress

and safety of the intervention.

Search methods

Data extraction and management

Data on patients, methods, interventions, control interventions, outcomes and results were extracted by two

authors independently using an a priori developed data

extraction form. Discrepancies were discussed with a

third review author until consensus was reached.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The risk of bias was assessed by two authors independently using the risk of bias tool proposed by the Cochrane

Back Review Group [8]. This tool assesses the risk of

selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, reporting

bias and detection bias using 12 criteria (ratings: low, unclear or high risk of bias). Differences of opinion were discussed with a third review author until a consensus was

reached. Studies that met at least 6 of the 12 criteria and

had no serious flaw were rated as having a low risk of

bias. Studies that met fewer than six criteria or had a serious flaw were rated as having a high risk of bias [8].

Quality of evidence

Based on the methodological quality and the confidence

in the results, the quality of evidence for each outcome in

each specific disease was assessed according to the

GRADE recommendations as high quality, moderate quality, low quality or very low quality [9].

Strength of recommendation

Based on the direction and quality of the evidence and

the risk of undesirable effects of the intervention, the

Results

Literature search

The literature search revealed 269 non-duplicate records,

of which 250 were excluded because they were not RCTs,

did not include patients with rheumatic diseases and/or

did not include yoga as an intervention. Of 19 full texts

assessed for eligibility, 5 articles were excluded because

they were either not randomized [1013] or did not include

yoga interventions [14]. Another article was excluded that

compared yoga with yoga combined with massage [15].

Thirteen full-text articles reporting on eight RCTs were

finally included in the analysis [1628] (Fig. 1).

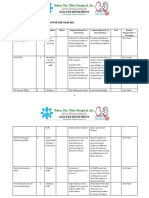

The characteristics and overall risk of bias of the

included studies are shown in Table 1. In-depth information on the characteristics and results of the included

studies can be found in supplementary Table S2, available

as supplementary data at Rheumatology Online.

Supplementary Table S3, available as supplementary

data at Rheumatology Online, shows a detailed risk of

bias assessment of the included studies. GRADE criteria

for each disease and outcome are shown in supplementary Table S4, available as supplementary data at

Rheumatology Online.

FM syndrome

An RCT with low risk of bias from the USA assessed the

effects of an 8-week Yoga of Awareness intervention

compared with usual care in 56 female FM patients

(mean age 53.7 years) [17, 18]. The yoga intervention

included yoga postures, meditation, breathing techniques

and lessons on yogic coping strategies. Outcome measures included pain, using number of tender points and

extent of tenderness, and disability, using the

Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ). Significant

group differences were found for disability only; no

safety data were reported.

A second RCT originated from Brazil, had low risk of

bias and assessed the effects of a water-based breathing

yoga intervention, 60 min four times a week over a period

of 4 weeks, in 40 female FM patients (mean age 46.06

years) [26]. The intervention included breathing techniques, but no yoga postures or meditation. Both the

intervention and the control group participated in recreational activities once weekly. This RCT reported significant group differences favouring the yoga group in pain

on a visual analogue scale (VAS), disability on the FIQ and

anxiety on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAS). No safety

data were reported.

Using the GRADE approach, the quality of evidence for

pain in FM syndrome was very low and the quality of evidence for disability was low. Overall, a weak recommendation can be made for the use of yoga in FM syndrome.

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Downloaded from http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 15, 2016

Medline/PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library and

IndMED were searched from their inception through

11 February 2013. The complete search strategies for

each database are shown in supplementary Table S1,

available as supplementary data at Rheumatology

Online. Reference lists of identified original articles or reviews and the tables of contents of the International

Journal of Yoga Therapy and the Journal of Yoga &

Physical Therapy were searched manually. Two review

authors independently screened abstracts identified

during the literature review and potentially eligible articles

were read in full to determine whether they met the eligibility criteria.

strength of the recommendation for or against yoga as a

therapeutic option for each specific disease was judged

according to the GRADE recommendations as either

strong or weak [9].

Yoga for rheumatic diseases

FIG. 1 Flowchart of the results of the literature search.

An Indian trial with a high risk of bias included 250 patients

with OA of the knee (69.9% female; mean age 59.49

years). This RCT compared a 2-week hatha yoga intervention including yoga postures, meditation, relaxation,

breathing techniques and lectures for 40 min each day

with an aerobic exercise intervention of matched intensity

[1922]. Significant group differences were found for pain

at rest and while walking assessed on a VAS, disability on

the WOMAC, all subscales of health-related quality of life

on the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) and anxiety

on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). While safety

data were not included, three drop-outs due to adverse

events in the control group and none in the yoga group

were reported [1922].

An RCT from the USA included 25 patients with OA of

the interphalangeal joints. The RCT had a risk of bias. Age

ranged from 52 to 79 years and 56% were female [24].

Compared with usual care, a 10-week Iyengar yoga intervention including 60 min of yoga postures, relaxation and

education twice weekly resulted in significant group differences in hand pain during activities on a VAS but not

in pain at rest on a VAS or disability on the Stanford

Hand Assessment Questionnaire. Safety data were not

reported [24].

Originating from the USA, a third RCT compared chair

yoga (sitting meditation) twice weekly for 45 min over

8 weeks with Reiki (a spiritual healing intervention) once

weekly for 30 min over 8 weeks [27]. Twenty-one patients

with OA of different joints were included (mean age 80.0

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

years). Significant group differences were found for the

WOMAC disability scale but not for the WOMAC pain

scale or depression on the Center for Epidemiologic

Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). No safety data were

reported [27].

According to the GRADE approach, the overall quality

of evidence for effects of yoga on pain and disability in OA

was graded very low. A weak recommendation can be

made for the use of yoga in OA.

RA

An RCT with a high risk of bias from the USA compared a

6-week Iyengar yoga intervention including yoga postures

and relaxation 90 min twice weekly with usual care [23].

The RCT included 30 young women (mean age 29.9 years)

with RA. The RCT found no group differences in bodily

pain on the SF-36. Significant effects were reported for

disability using the Health Assessment Questionnaire

Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and the Pain Disability Index

(PDI), for vitality and general health on the SF-36 and for

distress on the Brief Symptom Inventory. Safety was not

reported.

A second RCT originating from India had a high risk of

bias [28]. This RCT included 80 patients with RA (mean

age 35.08 years, 70% female). The yoga intervention

included postures, cleansing practices, breathing techniques, meditation and lifestyle advice for 90 min six

times each week for 7 weeks. Compared with usual

care, yoga significantly reduced pain on the Simple

Downloaded from http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 15, 2016

OA

RA

OA of the hand

CTS

FM syndrome

OA of the hip

or knee

RA

Evans et al. [23]

Garfinkel et al. [24]

Garfinkel et al. [25]

Ide et al. [26]

Park et al. [27]

FIQ-R: Revised FIQ.

Singh et al. [28]

OA of the knee

Ebnezar et al.

[1922]

Carson et al. [17, 18] FM syndrome

Rheumatic

disease

80

29

51

40

25

30

250

56

8

4

10

12

8

Exercise,

280 min/week

Usual care

Control

intervention

Yoga, 540 min/week

Chair yoga, 90 min/week

Iyengar yoga, 90 min/week

Yoga breathing exercise,

240 min/week

Iyengar yoga, 60 min/week

6 weeks

14 weeks

10 weeks

8 weeks

5 months

2 weeks

14 weeks

Outcome

assessment

Usual care

7 weeks

Wrist splint

8 weeks

Recreational

4 weeks

activities,

60 min/week

Reiki, 30 min/week 8 weeks

Usual care

Iyengar yoga, 180 min/week Usual care

Yoga of awareness,

120 min/week

Hatha yoga, 280 min/week

Sample

Treatment

size, n duration, weeks Experimental intervention

Downloaded from http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 15, 2016

Reference

TABLE 1 Characteristics of the included studies

Disability (WOMAC), depression

(CES-D)

Pain (SDPIS)

Pain (myalgic tender points), disability

(FIQ-R)

Pain (pain at rest, pain while walking

on VAS), disability (WOMAC), quality

of life (SF-36), anxiety (STAI), safety

(drop-outs)

Disability (PDI, HAQ-DI), quality of life

(SF-36), distress (BSI)

Pain (pain at rest, pain during activity

on VAS), disability (Stanford Hand

Assessment Questionnaire)

Pain (VAS)

Pain (VAS), disability (FIQ), quality

of life (SF-36), anxiety (HAS)

Outcome measures

High

High

High

Low

High

High

High

Low

Risk of

bias

Holger Cramer et al.

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Yoga for rheumatic diseases

Descriptive Pain Intensity Scale (SDPIS). Safety data were

not reported.

Using GRADE, the quality of evidence for the effects of

yoga on pain was graded as very low. Only a weak recommendation can be made for the use of yoga in RA.

Only two RCTs had a low risk of bias. Therefore, while

the effects for FM found in this review seem to be robust

against methodological bias, the effects found for RA and

OA have to be interpreted with care.

Limitations

CTS

A US RCT with a high risk of bias included 51 CTS patients (mean age 48.08 years, 54.9% female). The RCT

compared an 8-week Iyengar yoga intervention, 90 min

twice weekly, including yoga postures and relaxation,

with a standard wrist splint [25]. As this RCT did not find

significant group differences in pain on a VAS and did not

report safety data, no recommendation can be made for

or against yoga in CTS.

Discussion

Agreements with prior systematic reviews

The findings of this review are partly in line with a prior

systematic review that found evidence of the effectiveness of yoga in improving pain and mental health in

patients with OA and RA but concluded that the heterogeneity of studies precluded preliminary conclusions [4].

Based on the same RCTs as the present review [17, 18,

26], a systematic review on meditative movement therapies for FM found evidence of the effectiveness of yoga on

pain, depression and quality of life [5]. Mainly based on

low back pain studies, two recent meta-analyses on yoga

for musculoskeletal conditions [29] or pain [30] concluded

that there was good quality evidence of effectiveness on

pain and disability. Based on the same single RCT as the

present review [25], systematic reviews on conservative

treatment of CTS concluded that there was very limited

[35] to limited [36] evidence of the effectiveness of yoga in

this condition. A recent Cochrane review statistically reanalysed this RCT and found favourable effects of yoga

on pain [37].

External and internal validity

Patients of a wide age range with rheumatic diseases

diagnosed mainly by the ACR criteria were recruited

from secondary and tertiary care centres in North and

South America and Asia. Especially in RCTs on FM and

RA, mainly female patients were included. The results of

this review therefore seem to be applicable to most patients with rheumatic diseases in clinical practice while the

small number of studies on each disease limits this interpretation. The results for FM and RA might not be fully

applicable to male patients.

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Conclusion

Based on the results of this review, weak recommendations can be made for the ancillary use of yoga in the

management of FM syndrome, OA and RA.

Rheumatology key messages

A limited number of randomized trials have investigated yoga as a treatment for rheumatic diseases.

. Yoga might be considered as an ancillary treatment

for FM syndrome, OA and RA.

.

Funding: This work was supported by the Rut- and KlausBahlsen-Foundation.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no

conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology

Online.

References

1 Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB et al. Characteristics of

yoga users: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med

2008;23:16538.

2 Iyengar BKS. Light on yoga. New York: Schocken Books,

1966.

3 Feuerstein G. The yoga tradition. Prescott, AZ: Hohm

Press, 1998.

4 Haaz S, Bartlett SJ. Yoga for arthritis: a scoping review.

Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2011;37:3346.

5 Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ et al. Efficacy and

safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia

syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:

193207.

6 Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting

items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the

PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:2649.

Downloaded from http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 15, 2016

This systematic review of eight RCTs on yoga for rheumatic diseases found very low to low quality evidence

for FM, very low quality evidence for OA and RA and no

evidence for CTS. While no RCT reported safety data,

prior systematic reviews on other conditions found no evidence for severe adverse events [2934]. Therefore a

weak recommendation for the use of yoga as an ancillary

intervention in FM, OA and RA can be made.

The primary limitation of this review is the small number

and low methodological quality of the included RCTs.

Only for FM syndrome were high quality RCTs available

and the evidence drawn from these studies is still limited

by the heterogeneity of interventions and outcome measures. The evidence for effects on OA is further limited by

the heterogeneity of the affected joints studied in the

included trials. As no RCT reported safety data, the recommendations for yoga have to be regarded as preliminary until the safety of the interventions is clarified.

Holger Cramer et al.

8 Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C et al. 2009 updated

method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane

Back Review Group. Spine 2009;34:192941.

22 Ebnezar J, Yogitha B. Effectiveness of yoga therapy with

the therapeutic exercises on walking pain, tenderness,

early morning stiffness and disability in osteoarthritis of the

knee jointa comparative study. J Yoga Phys Ther 2012;

2:144.

9 Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. GRADE: an emerging

consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of

recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:9246.

23 Evans S, Moieni M, Lung K et al. Impact of Iyengar yoga

on quality of life in young women with rheumatoid arthritis.

Clin J Pain 2013.

10 Badsha H, Chhabra V, Leibman C et al. The benefits of

yoga for rheumatoid arthritis: results of a preliminary,

structured 8-week program. Rheumatol Int 2009;29:

141721.

24 Garfinkel MS, Schumacher HR Jr, Husain A et al.

Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of

osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol 1994;21:23413.

7 Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic

reviews of interventions. West Sussex, UK: Wiley, 2010.

11 Bedekar N, Prabhu A, Shyam A et al. Comparative study

of conventional therapy and additional yogasanas for knee

rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. Int J Yoga 2012;

5:11822.

13 Krejci M. Yoga training application in overweight control of

seniors with arthritis/osteoarthritis. Fizjoterapia 2011;19:

38.

14 Joshi A, Mehta CS, Dave AR et al. Clinical effect of

Nirgundi Patra pinda sweda and Ashwagandhadi

Guggulu Yoga in the management of Sandhigata Vata

(Osteoarthritis). Ayu 2011;32:20712.

15 da Silva GD, Lorenzi-Filho G, Lage LV. Effects of yoga and

the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern

Complement Med 2007;13:110713.

16 Bhandari R, Singh V. A research paper on effect of yogic

package on rheumatic arthritis. Ind J Biomechanics 2009;

Special Issue (National Conference on Biomechanics

2009):1759.

17 Carson JW, Carson KM, Jones KD et al. A pilot

randomized controlled trial of the Yoga of Awareness

program in the management of fibromyalgia. Pain 2010;

151:5309.

18 Carson JW, Carson KM, Jones KD et al. Follow-up of yoga

of awareness for fibromyalgia: results at 3 months and

replication in the wait-list group. Clin J Pain 2012;28:

80413.

19 Ebnezar J, Nagarathna R, Bali Y et al. Effect of an

integrated approach of yoga therapy on quality of life in

osteoarthritis of the knee joint: a randomized control

study. Int J Yoga 2011;4:5563.

20 Ebnezar J, Nagarathna R, Yogitha B et al. Effects of an

integrated approach of hatha yoga therapy on functional

disability, pain, and flexibility in osteoarthritis of the knee

joint: a randomized controlled study. J Altern Complement

Med 2012;18:46372.

21 Ebnezar J, Nagarathna R, Yogitha B et al. Effect of

integrated yoga therapy on pain, morning stiffness and

anxiety in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: a randomized

control study. Int J Yoga 2012;5:2836.

26 Ide MR, Laurindo IMM, Rodrigue AL et al. Effect of aquatic

respiratory exercise-based program in patients with

fibromyalgia. Int J Rheumat Dis 2008;11:13140.

27 Park J, McCaffrey R, Dunn D et al. Managing osteoarthritis: comparisons of chair yoga, Reiki, and education

(pilot study). Holist Nurs Pract 2011;25:31626.

28 Singh VK, Bhandari RB, Rana BB. Effect of yogic package

on rheumatoid arthritis. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 2011;

55:32935.

29 Ward L, Stebbings S, Cherkin D et al. Yoga for functional

ability, pain and psychosocial outcomes in musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Musculoskeletal Care 2013.

30 Bussing A, Ostermann T, Ludtke R et al. Effects of yoga

interventions on pain and pain-associated disability:

a meta-analysis. J Pain 2012;13:19.

31 Cramer H, Lange S, Klose P et al. Yoga for breast cancer

patients and survivors: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2012;12:412.

32 Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H et al. A systematic review

and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain

2013;29:45060.

33 Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P et al. Yoga for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC

Psychiatry 2013;13:32.

34 Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J et al. Effectiveness of

yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:863905.

35 Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B. What can family physicians

offer patients with carpal tunnel syndrome other than

surgery? A systematic review of nonsurgical management.

Ann Fam Med 2004;2:26773.

36 Piazzini DB, Aprile I, Ferrara PE et al. A systematic review

of conservative treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin

Rehabil 2007;21:299314.

37 Page MJ, OConnor D, Pitt V et al. Exercise and

mobilisation interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6:CD009899.

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Downloaded from http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 15, 2016

12 Haslock I, Monro R, Nagarathna R et al. Measuring the

effects of yoga in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol

1994;33:7878.

25 Garfinkel MS, Singhal A, Katz WA et al. Yoga-based

intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized

trial. JAMA 1998;280:16013.

You might also like

- Penetrating Traumatic Brain Injury A Review of Current Evaluation Andmanagement Concepts 2155 9562 1000336Document7 pagesPenetrating Traumatic Brain Injury A Review of Current Evaluation Andmanagement Concepts 2155 9562 1000336PrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Eyes in Marfan SyndromeDocument8 pagesEyes in Marfan SyndromePrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Article Wrist Hand CTS MGT October2004 JOSPT MichlovitzDocument12 pagesArticle Wrist Hand CTS MGT October2004 JOSPT MichlovitzPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Marfans Occular ReviewDocument3 pagesMarfans Occular ReviewPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Article Wrist Hand CTS MGT October2004 JOSPT MichlovitzDocument12 pagesArticle Wrist Hand CTS MGT October2004 JOSPT MichlovitzPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- BR J Ophthalmol 2001 Falkner 1324 7Document5 pagesBR J Ophthalmol 2001 Falkner 1324 7PrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- 0915RT Mini Cousins Wolfe YonekawaDocument5 pages0915RT Mini Cousins Wolfe YonekawaPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- BR J Ophthalmol 2015 Danis Bjophthalmol 2015 306823Document7 pagesBR J Ophthalmol 2015 Danis Bjophthalmol 2015 306823PrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 HMS Siklus MenstruasiDocument18 pagesLecture 5 HMS Siklus MenstruasiPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Appendix RismanDocument45 pagesAppendix RismanPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- UK National Guideline For The Management of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease 2011 PDFDocument18 pagesUK National Guideline For The Management of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease 2011 PDFPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- 08 - GlaucomaDocument80 pages08 - GlaucomaabcdshNo ratings yet

- 084 Prissilma Tania JonardiDocument1 page084 Prissilma Tania JonardiPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Modul 7Document31 pagesModul 7PrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Dr. H. I. Dr. H. I. Boediman Boediman,, Sp.A Sp.A (K) (K) : B Fdiii FR IlDocument49 pagesDr. H. I. Dr. H. I. Boediman Boediman,, Sp.A Sp.A (K) (K) : B Fdiii FR IlPrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- Hostel Murah Di SingaporeDocument22 pagesHostel Murah Di SingaporePrissilmaTaniaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Aneurizma Bazilarke I TrombolizaDocument4 pagesAneurizma Bazilarke I TrombolizaAnja LjiljaNo ratings yet

- NRP 2015 7th Ed Update 04 2017 Claudia ReedDocument53 pagesNRP 2015 7th Ed Update 04 2017 Claudia Reeddistya.npNo ratings yet

- Kode Akses UAS Gasal 2021-2022 RegulerDocument5 pagesKode Akses UAS Gasal 2021-2022 RegulerGaluh Restuti Dyah PradwiptaNo ratings yet

- Bentuk-Bentuk Terapi KomplementerDocument21 pagesBentuk-Bentuk Terapi KomplementeraikocanNo ratings yet

- Magnification and IlluminationDocument22 pagesMagnification and Illuminationwhussien7376100% (1)

- MCQs in DentistryDocument135 pagesMCQs in Dentistryyalahopa75% (4)

- Neonatal PneumoniaDocument2 pagesNeonatal PneumoniaJustin EduardoNo ratings yet

- Chelation of Gadolinium Oxford 2009Document3 pagesChelation of Gadolinium Oxford 2009gasfgdNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Delayed SpeechDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Delayed SpeechAndi Tri SutrisnoNo ratings yet

- Staff Development Plan 2023Document5 pagesStaff Development Plan 2023SSNHI Dialysis Training CenterNo ratings yet

- Body Part Assessed Technique Used Actual Finding Interpretatio N SkinDocument3 pagesBody Part Assessed Technique Used Actual Finding Interpretatio N SkinSkyerexNo ratings yet

- Non-Retentive Adhesively Retained All-Ceramic Posterior RestorationDocument13 pagesNon-Retentive Adhesively Retained All-Ceramic Posterior RestorationMarian ButunoiNo ratings yet

- 2008 Annual Report-From ILAEDocument113 pages2008 Annual Report-From ILAEarmythunder100% (2)

- Deep Neck Space InfectionDocument48 pagesDeep Neck Space InfectionhaneiyahNo ratings yet

- May 17, 2013 Strathmore TimesDocument36 pagesMay 17, 2013 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Examples For Mara EssayDocument26 pagesExamples For Mara EssayMuizzuddin Nazri100% (1)

- 2019 Afk ProtocolDocument10 pages2019 Afk Protocoldrsunny159840% (1)

- Open Sim Tutorial 1Document10 pagesOpen Sim Tutorial 1Rayanne FlorianoNo ratings yet

- Sepsis Induced CholestasisDocument12 pagesSepsis Induced CholestasisYusuf Hakim AjiNo ratings yet

- Medical Treatment For Dandruff: in This Leafl Et: 2. Before You Use Selsun ShampooDocument2 pagesMedical Treatment For Dandruff: in This Leafl Et: 2. Before You Use Selsun ShampooCharles Franklin Joseph100% (1)

- Warfarin Dosing PDFDocument3 pagesWarfarin Dosing PDFOMGStudyNo ratings yet

- Case Report PresentationDocument41 pagesCase Report PresentationlukitaniningNo ratings yet

- Biomechanics of The HipDocument12 pagesBiomechanics of The HipSimon Ocares AranguizNo ratings yet

- Lingual Frenectomy With Electrocautery: Diagnostic Assessments For Case in PointDocument5 pagesLingual Frenectomy With Electrocautery: Diagnostic Assessments For Case in PointTasneem AbdNo ratings yet

- Nurse AnesthesiaDocument3 pagesNurse Anesthesiaapi-348841675No ratings yet

- FMGE Information BulletinDocument17 pagesFMGE Information Bulletinmahesh100% (4)

- Raja Rajeshwari Medical CollegeDocument11 pagesRaja Rajeshwari Medical CollegepentagoneducationNo ratings yet

- Cerebral PalsyDocument21 pagesCerebral Palsysuryakoduri93% (14)

- Constancia VisualDocument221 pagesConstancia VisualKaren CastroNo ratings yet

- AccreditationReadiness Booklet (Version 1.0) - May 2022Document44 pagesAccreditationReadiness Booklet (Version 1.0) - May 2022Leon GuerreroNo ratings yet