Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance examines relationship between fraud and financial crises

Uploaded by

madaharimOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance examines relationship between fraud and financial crises

Uploaded by

madaharimCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance

Volume 11 Number 1

Crisis and fraud

Pascal Blanque

Received: 6th March, 2002

Caisse Nationale de Credit Agricole, Dept of Economics and Banking Research, 91 Boulevard

Pasteur, 75710 Paris, France; tel: +33 143 23 5202; fax: +33 143 23 5202

Pascal Blanque is Chief Economist with

Credit Agricole SA in Paris. He previously

served as an asset allocation strategist

with Paribas Asset Management in

London, and as Deputy Chief Economist at

Paribas in Paris. Mr Blanque holds

degrees from Ecole Normale Superieure

and Institut dEtudes Politiques, and

earned a PhD in nance at the University

of Paris-Dauphine. A member of numerous

economic and banking organisations, he

serves on the Economic and Monetary

Aairs Committee of the European Banking

Federation. He has published in trade and

academic journals, and is an economic

and nancial editorialiste with Le Figaro.

Journal of Financial Regulation

and Compliance, Vol. 11, No. 1,

2003, pp. 6070

# Henry Stewart Publications,

13581988

Page 60

ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the relationship between

fraud and nancial crises. Fraud is envisioned

historically as a violation of trust, and the classic triangle of smuggling, contraband and enforcement sheds light on developments in the

nancial sphere. Schematically, fraud emerges

with economic prosperity, grows in a nancial

crisis when prices fall, and culminates in crash

and panic when the scandal is revealed. Kindleberger points out that the propensity to defraud

increases with the speculation that accompanies

a boom. Fraud is recognised as a coincident

indicator of prosperity.

The paper considers the implicit consensus

view that fraud and the cycle are linked, with

long cycles including alternating phases of liberalisation/globalisation and contraction. If fraud

is part of the cost of learning to deal with new

elds and new frontiers in the appetite for risk,

then fraud and crisis will inevitably nd a

fertile breeding ground in globalisation.

Topics discussed include the distortion of

decision-making, the structure of incentives,

information and regulatory implications.

INTRODUCTION

Theory which determines the rules

can hardly be expected to start by looking

at the exceptions. Unsurprisingly, neither

fraud nor crisis gures high on the list of

topics in the literature of economics, and

even less has been written on the relationship between the two. Still, there is no lack

of reminders of their largely intangible,

hard-to-quantify and fundamentally elusive

nature: crisis and fraud are concepts that

are often forged by situations recognised as

such only after the event, once the mischief

has created a grey area that is eventually

declared o limits. With the notable exception of Charles Kindleberger,1 the theme

has been largely avoided by mainstream

economists.

AN ELUSIVE CONCEPT

Kindlebergers characterisation of nancial

crisis can be readily extended to encompass

the relationship between nancial crises

and fraud: like pretty women [. . .], hard

to dene but recognizable when encountered.2 Crisis and fraud have a long-standing but paradoxical association.

Blanque

The long history of fraud

Fraud is neither new nor easy to characterise. Ethical, legal, institutional and economic aspects are interrelated from the

outset. Fraud usually implies deceit or bad

faith, as opposed to good faith, integrity

and honesty. In ancient Rome, fraud comprised the intent to circumvent the law,

with a connotation of deceit: legi fraudem

facere.3 Fraud was characterised in legal

terms (breach of contract) and moral

terms; commercial and nancial crises were

linked to transactions that violate law and

ethics, and the detection of fraud was

accordingly incumbent upon the State.

Throughout history, fraud has been intimately related to trade in goods eg

smuggling to avoid customs duties or concealment of the true origin of a product

and to prot: Boni nullo emolumento impelluntur in fraudem4 (there is no gain that can

induce good men to act badly).

Fraud has always been at the heart of the

creditordebtor relationship (in fraudem

creditorum, to defraud creditors), a legal

adage that dates back to the Codex of Justinian (alienatio in fraudem creditorum facta);

this provides the most commonly recognised tie-in with nance. Fraud also refers

to the alteration of an object or product,

through which the fraud is perpetrated

livestock yesterday, derivatives today.

Frauds involving livestock included and

probably still include ways to make livestock appear larger, heavier, healthier or

younger, eg by ling down the rings on

horns or by ling teeth. Cattle fraud,

including selling watered meat, was also

common, as was passing o horsemeat for

beef. Along the same lines, in the American Express incident in the late 1960s,

tanks of salad oil were lled, except for

the top, with water.5 Stories abound of

railways without rails during various

booms in the 19th century.

The triangle of fraud has changed little

over the years. Fraud has long been

associated with a practice (smuggling), a

domain of economic activity (merchandise)

and the violation of that domain, and a

player empowered to ght against it (the

fraud squad). Contemporary players in

fraud include investors defrauded by nancial professionals (brokers or bankers), the

State defrauded by its citizens, and, often,

rms defrauded by their employees or ocers. Major contemporary nancial frauds

in the latter category were perpetrated by

Nick Leeson ($1.4bn), Victor Gomez (Chemical Bank, $70m), Toshihide Iguchi

(Daiwa Bank, $1.1bn) and Roberto Calvi

(Banco Ambrosiano). Financial ows, regulatory watchdogs and sophisticated information systems have simply updated the

classical triangle of smuggling, merchandise

and fraud squads.

A relative concept that is hard to

quantify

Fraud is neither theft nor corruption. Fraud

is an immoral transaction that violates an

implicit or explicit contractual relationship

of trust between groups of persons. Many

writers, or their ctional characters (including Balzacs Pe`re Grandet), have described

fraud artists as worse than highway robbers.6 Nor is fraud entirely the same as

crime, though the distinction may appear

tenuous. Criminal nancial channels play a

role in nancial crises that involve funds

under discretionary management in oshore banking or tax havens, or the laundering of money resulting from crime,

corruption or bribery. Alternatively, the

aim can be to avoid taxes on otherwise licit

activities. The amounts are hard to evaluate, but are no longer negligible. Hedge

funds can draw money from illicit activities

to oshore centres. Money laundering currently comes to some US$600bn a year, or

2 per cent of global gross domestic product

(GDP). The relationship between these

phenomena and nancial crises has been

identied; in particular, there is evidence of

Page 61

Crisis and fraud

a correlation between the level of corruption and vulnerability to crises.

Fraud often begins as a legitimate business activity operating within the law.

Frontiers between legality and illegality, or

between what is moral and immoral, can

shift over time. What was not a fraud in

the past can become one. The terrain and

frontiers of fraud are malleable. For a long

time, developed markets operated with

practices and instruments that would be

considered fraudulent today. The forms of

fraud have multiplied as they diversied.

Recent instances have seen ineectual risk

control (with a poorly identied derivatives position in the Barings case), dangers

of embezzlement (Codales, Barings),

underestimation of commitments (Metallgesellschaft), or poor understanding of

sophisticated operations (Procter and

Gamble).

Finally, as Kindleberger points out, there

are no rm statistics on which to base a

judgment.7 Fraud is an iceberg: only a

fraction of practices are brought to the

knowledge of the public, most often by

the media. Fraud and statistics are simply

not good bedfellows.

Fraud and trust

The relationship between economic eciency and trust can be stretched at times,

even to breaking point. Fraud springs up in

the breach; indeed, fraud is a breach of

trust. Currency and nance have long been

tokens of trust in society, and have played

a delicate, complicated role in social regulation. Trust guarantees a systems stability,

and a breach of trust is strictly speaking a

crisis, which can be a nancial crisis. Fraud

is accordingly a violation of des, or the

good faith and trust enjoyed by someone

who gives his word; the goddess Fides provided protection for contracts, pacts and

promises. In ancient Rome, this is the trust

that mortals placed in their gods, who

guaranteed them protection in return

Page 62

with a guarantee that is invoked in the distress of a crisis.

Credence, or belief (credere, from the

radical *kred, faith, which literally means

to place faith, to entrust) leads to the concept of a deposit given in trust, hence a

pledge received from the gods. Fides is ultimately credit received from another person

and from the gods, as the goddess Fides

presides over all contracts, pacts and promises, including in nancial matters. Her

temple is where deposits are taken and

debts are negotiated. Fides Publica provides

her protection during the nancial crises of

the Republic, and people turned to her

during periods of distress.8 According to

Cicero, nothing, in eect, guarantees more

forcefully the permanence of the State than

good faith, which cannot exist if each is

not obliged to pay his debts.9 During the

monetary crises of the rst century BC,

Rome struck coins with the gure of Fides

Publica. And the rst public banks in

Genoa and Venice also invoked Fides Publica in the mid-16th century.

Distortion of decision-making, the

structure of incentives and information

The Greek krsizs (crisis) denotes a decision, a struggle or trial, or the critical stage

in an illness. Crisis occurs where there is a

perversion of a decision (or decisionmaking process); fraud is also a heresy of

the decision-making process. Fraud is a

matter of not keeping ones word. People

are creditable because their word carries

weight. This remains true even in our

time. Traders would prefer to violate their

rules or limits, rather than go back on their

word. Fraud can arise from the consequences of decisions often legal ones

under which a promise can be kept only

by breaking the law.

Numerous contemporary frauds can be

traced to decisions made by traders. At

Barings, Nick Leeson added fraud to deceit

in his desperate attempt to avoid going

Blanque

back on his word. A ctional parallel is

found in Balzacs tale Melmoth reconcilie,

in which the bank teller Castanier sinks

ever deeper into debt to satisfy his mistress

whims, until, reaching the point of no

return, he prefers fraud to honest bankruptcy and dips into the banks till.10 The

Lloyds incident in the 1980s threatened to

ruin the prestigious names, who had committed their personal fortunes to guarantee

the insurance policies issued by the institutions partners. As early as 1969, with the

rst claims by victims of pneumoconiosis

(resulting from inhalation of asbestos dust),

Lloyds knew that the situation was potentially perilous and it actually became so

in the late 1970s. Yet the information was

concealed, and losses were hidden over

time. Recruitment of new names (who

assumed their share of liabilities) became a

strategy to increase the capital base.

It may be in the employees interest to

defraud a rm if he or she is not caught

and/or if the ne is lower than the gain.

That, in any event, is suggested by work in

the economics of crime following Gary

Beckers pioneering studies in the late

1960s.11 The cost to the criminal, and

therefore the disincentive, is linked to the

extent of enforcement. Fraud is accordingly connected to the economics of crime

and enforcement (with the state delegating

part of its power to banks and other nancial institutions). This raises the issue of the

structure of public incentives, often

described in the form of a principalagent

model in which the state incites the banking and nancial system to cooperate.

But there is more. The structure of private incentives creates internal corporate

discipline, with management ensuring

compliance. Incentives in each unit must be

consistent with the institutions overall

objectives. The structure, however, can

collapse. Nick Leeson needed funds to

nance losses and margin calls on the

SIMEX for the transactions booked to

account 88888: since the funds came from

other enterprises in the group, how could

he get US$1.7bn without being asked to

justify it? More tellingly, the Barings incident showed that the apparent consistency

between corporate protability objectives

at head oce and cash incentives for traders could be illusory. Operators attitudes

can also be called into question; a current

example in nancial markets is the primacy

of short-term gains and the compensation

system for traders. Lastly, the structure of

private incentives is not always suited to

nancial modernisation and globalisation,

which may demand a review of existing

regulations to make sure they do not distort private incentives. More generally, this

movement paralleled the growing focus on

ethical issues in the 1980s and the greater

importance given to business ethics courses

in business schools.

These approaches do not exhaust the

subject. The behaviour of agents engaged

in illegal activities depends not only on

cost considerations but also on strategic

choices intended to ensure smooth transactions. Under this reading, fraud depends

not only on gains, but also on the perpetrators ability to dominate the inherent

risks of his or her illegal activity. The

importance given to transaction costs in the

work of economists, and particularly by

Oliver E. Williamson in the mid-1970s,

shows a methodological renewal in the

area.

Lastly, at the heart of every transaction

and fraud is only a special case there

typically exists an informational asymmetry, with each party concealing something

from the other. And the information itself

is eeting. Exact information on risk can

be dicult to obtain in an environment

where risk can be repackaged, wrapped

and securitised. Further, information systems and nancial control have not totally

come to grips with the pace of nancial

innovation and the impact of the growing

Page 63

Crisis and fraud

use of derivatives on market dynamics.

These are just some of the predominant

aspects of the issue at present.

BOOM, FRAUD, CRASH

While frauds, and the connection between

frauds and crises, are deeply rooted in the

past, more recent times, and singularly the

20th century, have given a new twist to

many aspects of the issue. The rise of

market economies and changes in their

modes of nancing, including growing

intermediation of the nancial markets,

have acted as an accelerator in the linkage

between fraud and crises.

Economic cycle, public authority and

fraud

Late in the 19th century, linkages were

identied between the business cycle and

the credit cycle, and therefore with the

attitude of the monetary authorities. The

dominant idea became that frauds occur

when the attitude of the monetary authorities is too accommodating. The ultimate

cause of nancial crises (and fraud) was

considered to be excess liquidity poured

into the economy and markets. The authorities (and legislator) were held responsible

for economic uctuations, and they were

then expected to adjust the laws as required

to manage and rectify those uctuations

when a crisis occurred. Up to then, at the

risk of oversimplifying, the interpretive

framework was based to a large extent on

stable legal standards and independent economic uctuations. Fraud accordingly

involved circumventing the standards. In a

sense, these two models continue to coexist

today, in the same way as, for instance,

state-levy systems (emerging countries) and

nancial innovations (globalisation).

Are market and economic liberalisation

more or less conducive to frauds (the contemporary form created and developed on

the nancial markets) than to controlling

those frauds (with fraud under the earlier

Page 64

system essentially a matter of dodging government rules, especially regarding taxation)? At the risk of oversimplifying again,

the liberal thesis holds that fraud exists

because the economic eld is neither open

enough nor transparent enough, or because

there are too many interventions (by governments, lenders of last resort). Others

hold that market liberalisation has multiplied the grey areas, continuously distorting the reference frame for public

information, forcing the authorities to play

catch-up.

Is there something inevitable in the triptych formed by the receding horizon of

state control, tyranny by the markets and

frauds? Yes, one might be tempted to

answer, because the phenomenon is especially evident in the environment of a

nancialised economy. On the other hand,

ancient tyrants, dictators of all epochs and

dishonest dealing before the advent of

modern technology all suggest that this is a

long-standing theme. The dierence now

is doubtless due to abundant technological

resources, a growing nancial base, a clear

increase in technical stratagems, and greater

media coverage. This has redened the

linkages between fraud and regulation.

Recognition of a market imperfection

legitimates government intervention, and

economists are inclined to support regulation to curb misdeeds when negative

externalities include market disruption.

The consensus basically forms around

the simple, powerful idea that fraud and

the cycle are linked. The term cycle refers

to the business cycle (including credit), the

political and institutional cycle (particularly

in countries where there is rent capture),

the cycle of nancial innovations (resulting

in new products), and the cycle of reforms

(eg the consequences of the Savings and

Loans crisis in the USA in the late 1980s).

In any event, there tends to be agreement

that long cycles include alternating phases

of liberalisation/globalisation, and phases of

Blanque

contraction. Fraud remains present, changing more in its outer form than in its

inner nature, driven by hubris that is part

of human nature. As long as there are men,

there will be animal spirits.

Sequences and schemes

Three sequences act as the fundamental

matrices of the relations between crisis and

fraud in the contemporary world. Fraud is

born with economic prosperity, grows in a

nancial crisis when prices fall, and leads to

crash and panic when the scandal is

revealed. Fraud is a moment of the nancial crisis. Kindleberger points out that the

propensity to defraud increases with the

speculation that accompanies a boom.

Fraud is accordingly a coincident indicator

of prosperity and increases as prosperity

increases. Prosperity nourishes fraud in its

bosom, as it were, and, from an economic

point of view, it is determined by demand.

The subsequent economic crisis provides an

additional reason to defraud, in order to

save oneself. And in the panic, as each

person rushes to the exit, what is rational

behaviour individually exacerbates the risk

prole of the nancial community. The

denouement cannot be far behind.

Practices may vary but the recipe is

timeless. John Blunt of the South Sea

Company, Bontoux of the Union Generale, and the directors of the Creditanstalt

(which fell in 1931) all tried to support

their stock by buying it on the open

market . . . in order to sell more later.12 In

the South Sea bubble at the start of the

18th century, the protagonists, with John

Blunt in the lead, sought to make prots

on the stock issued to themselves against

loans secured by the stock itself. Capital

gains were converted into real estate. In

order to pay out prots, the South Sea

Company needed both to raise more capital and to have the price of its stock

moving continuously upward.13 When

capital inows slowed, Blunt dishonorably

borrowed the cash of the . . . company for

himself.14 In the 1920s, Albert Wiggins of

the Chase Bank and Charles E. Mitchell of

the National Security Bank marketed

securities intensely, all the while knowing

the problems ahead (that the foreign governments had stopped paying interest on

their bonds), and engaged in self dealing

at the expense of [their] banks.15

The heart of the matter is always the

same an accumulation of promises to

pay and their monetisation: the basic principle of selling the same horse twice, or

more, has not changed much.16 What the

practice is called has varied. Ponzi nance,

named after the notorious speculator, has

come to designate a nancial activity in

which the interest charge exceeds the enterprises cash ow and debt can be repaid

only by issuing further debt. The temptation to act this way may increase as a function of the degree to which a player

controls market prices. Such activities can

be built on a diverse set of underlyings,

including commodities and capital market

operations. When loans are backed by

commodities, a collapse in prices can set o

a failure. One of the greatest Ponzi schemes

was the one masterminded by Steven Hoffenberg, who ran the Towers Financial

Corporation of New York, and which cost

investors some US$450m between 1987

and 1993. The US Savings and Loans,

aected by rising interest rates in the early

1980s, oered very high interest rates to

attract deposits and extended loans in order

to pay interest on those deposits. In a different area, during the Russian crisis,

Ukraines central bank lent to a CSFB subsidiary in Cyprus, which then redeposited

the funds with the central bank. Not only

did this articially swell currency reserves

(because of double counting though not

everything returned to the central bank),

but there was also unjust enrichment

(resulting from the dierence between the

6 per cent rate paid by CSFB on deposits

Page 65

Crisis and fraud

and the 40 per cent to 80 per cent rate paid

on Ukraine Treasury bills).

What underlies this perversion is basically a confusion between money and savings, and misapprehension of the

inationary consequences of monetary

expansion. Is fraud a product or a residue

of ination? The debate exists because ination spurs risk-taking in order to increase

or maintain income. Inversely, lax monetary policies in a period of near-zero ination may be an open invitation to fraud

(with the formation of credit bubbles).

Indeed, history teaches that price stability

and nancial stability are rarely compatible. The centurys major bubbles (in 1929,

1990 and, possibly, 2000) occurred in periods of near-zero ination.

In each case, a false sense of security

prompted the monetary authorities to

maintain too lax monetary policies for

too long. Every story of credit bubble,

fraud and crisis begins with a period of

bliss but ends unhappily because the

authorities lost sight of the lagged eects

of their policies.

Not all bubbles are connected to frauds,

and not all frauds, not even the most publicised ones, lead to crises. The Barings

failure in February, 1995 and Daiwas billion dollar loss were shocks, but failed to

bring the system down. Similarly, the

Lloyds aair had no linkage to a nancial

crisis.

Pressure can lead to an attempt to transfer losses to others, amplifying the crisis

and leading to crisis. Kindleberger discusses

two similar cases. In 1857, a cashier at the

Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, a

highly reputable institution, engaged

nearly the entire assets of that company to

sustain his stockmarket operations. The

news sent dominos falling from Liverpool

to Stockholm. In September, 1929, the

Hatry empire a pyramid of small investment trusts that Hatry was trying to

parlay into a larger operation in steel

Page 66

collapsed when he was caught using fraudulent collateral in an attempt to borrow

. . . to buy United Steel. The operation

failed and the ensuing liquidity crisis lit the

powder keg on the stock market.17

But the scenario is never written in

advance. Fraud may invite further fraud,

bringing amateurs into the game; the dilettantes make matters worse.18 Revelation of

fraud can trigger a crisis. At this stage, the

media play an ambiguous role, throwing

oil on the ames and/or participating in

informing the public. Manipulation cannot

be ruled out: the banker Latte was not

the only nancier to fund newspapers.

The terminal phase is one of sudden

awareness and catharsis, with individuals

sometimes committing suicide or eeing,

and authorities reviewing regulation. The

phase of revelation, which allows progress

towards the phase of awareness, is a key

moment. Revealed fraud marks the end of

euphoria and signals the transition from

boom to bust. Charles Blunt, the brother of

John, who was also involved in the South

Sea bubble, cut his throat in September,

1720, Euge`ne Bontoux went into exile for

ve years.19 At the time of the South Sea

bubble, one member of the House of Commons suggested the ancient Roman punishment, that the transgressors should be

sewn into sacks, each with a monkey and a

snake, and drowned.20 While the history

of fraud tends to repeat itself, punishment

can take quite unexpected turns.

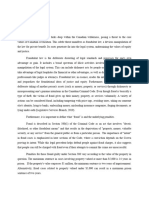

In such a model, there exist links

between bank failure and fraudulent practices. In a survey of factors leading to bank

insolvency, fraud ranked in a signicant

third position (see Figure 1). Fraud perverts

the functioning of the economy, alters

demand for money without regard to the

economic fundamentals, increases interestrate volatility, disrupts public nance and

contributes to speculative bubbles, because

the price and security of nancial assets are

distorted.

Blanque

Figure 1 Explanations of bank insolvency (based on a sample of 29 institutions)21

Inadequate control and regulation

Poor bank management

Political interventions

Lending to related parties

Lending to state enterprises

Fraud

Massive withdrawals

Failure of legal system

Decline in terms of trade

Recession

Asset price bubble

Capital ight

26

20

11

9

6

6

2

2

20

17

6

2

0

Despite new forms of fraud or new

places where it can crop up, there seem to

have been no major changes in 250 years,

despite regulatory and legislative eorts,

and the emergence of new counter-powers,

of which the press is only the visible tip. In

particular, there is no fraud without risktaking. The appetite for risk is at the heart

of the functioning of the nancial markets

which provide a framework for risk by

assigning it a price. That framework can be

circumvented, giving rise to the grey area

where fraud is situated.

Appetite for risk and the grey area of

fraud

Fraud is linked to the ease with which

funds can be raised. It accordingly results

from the very functioning of the credit

market, and from excess credit in particular. The credit market functions on the

basis of public information, condence and

unwritten standards, ie what bankers consider to be acceptable at a given point in

time. There is accordingly a grey area

between legal uncertainty and fraud.

A shift in where the needle points on the

scale of risk appetite or aversion will in

turn move the needle between information, condence and standards. The contemporary expansion in opportunities for

10

15

20

25

30

risk-taking and the growing recourse to

market nancing have given the phenomenon a new magnitude. As both the starting point and a paradigm model, the credit

marketplace provides an arena for dierent

degrees of appetite for risk. Global monetary and nancial instability and/or disorder, and increased volatility, however,

provide a fertile breeding ground for

fraud. Fraud, in eect, involves a calculation of fraud (expected gain, losing sight of

risk), and therefore a shift in the relationship between risk and return on investment. Derivatives markets result from this

state of events. Monetary crises and bank

crises are accordingly inseparable. Financial

crises result from what are identied after

the event as failures in risk control by

market players.

Appetite for risk rises with increased

demand for return on investment; this is

true for fund managers and for heads of

businesses alike. This can occur when

monetary policies are too accommodating

or when a regime of unrealistic expectations becomes dominant. Can nominal

earnings growth of all listed companies

lastingly exceed nominal GDP growth (of

5 per cent) with ination running at 2.5

per cent, as Wall Street seemed to believe

in the 1990s? Can shareholders expect

Page 67

Crisis and fraud

long-term double-digit returns and still

believe that equities are the least risky

investment? Strong incentives for fraud

may arise from the quest for performance

(for individual employees or the rm) and/

or when nancial markets expectations are

unrealistic in light of macroeconomic realities. This can lead to unreasonable management, with underestimation of the actual

risk being run.

Fraud is part of the cost of learning to

deal with a new eld (possibly one opened

by a nancial innovation) and a new frontier in the appetite for risk. Globalisation

opens new ground, which also has its

learning costs, so fraud and crisis will inevitably nd a fertile breeding ground in

globalisation.

The learning cost is even higher when

there is a poor grasp of the international

dimension of operations by banks that are

nominally subject to the supervision of

national authority. The Russian crisis

exposed gaps in national and international

controls over oshore capital movements

(with the Jersey-based Fimaco shell). Also

during the Russian crisis, out of a

US$4.8bn tranche allocated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in July, 1998,

US$1bn was earmarked to the Russian

nance ministry, and US$3.8bn was to be

sold on Moscows interbank currency

market to support the ruble. In fact, the

US$3.8 billion was reportedly transferred

immediately to the overseas accounts of

Russian commercial banks. The dollars

sold never returned to Russia, and the

commercial banks nanced the purchases

by selling their state short-term obligations

(GKOs) (a move linked with the crisis).

More generally, the concept of sovereign

legal spaces is sometimes unsupported by

the facts, and a unied legal space may

fail to obtain. The same holds for the

development of geographical black holes

(corrupt sovereign states, or oshore operations) and technical black holes (where

Page 68

only the formal regularity of operations is

veried).

Classical French theatre demands the

dramatic unities of action, place and time.

After looking at legal spaces, what can be

said about the time dimension? While legal

standards (and informational standards) are

xed, appetite for risk shifts swiftly. From

this standpoint, fraud is an ex post construct: after crises there is need for information, and in the process of revising attitudes

toward risk, some things that were not

previously fraud are subsequently characterised as such. That LTCM in early 1998

had commitments of US$120bn and assets

of US$4.8bn does not constitute a fraud,

but could be fraud if limits were imposed

on leverage.

The stylised schema unfolds in the following way: development, nancial markets, nancial innovations, appetite for

risk, grey areas, and then regulation of the

grey area with the emergence of legal standards after the event. After the bubble

pops, the ground of legal standards shifts.

Fraud can be seen as a form of noise that

accompanies or follows periods of extreme

shifts in the appetite for risk. Credit alone

can keep up with the appetite for risk,

until the inevitable adjustment comes.

Financial innovation is one of the contemporary channels conveying the distortion in the ground of risk. Financial

innovations (eg hedge funds) bring forth

rules or standards to control them. Financial innovations have accordingly led to

diversication of banks sources of capital,

which might not always qualify as equity

capital (eg foreign-currency denominated

securities including conditional nancial

undertakings by subscribers). Financial

innovations may sometimes be used to circumvent the constraints of the Cooke

ratio, as in the case of some securitisation

operations intended to reduce the denominator in capital adequacy ratios. Finally,

counterparty

risk

on

derivatives

Blanque

(US$1.2trillion, according to Bank for

International Settlements estimates) is a

source of complexity and sometimes leads

to excessive risk taking. The need to hedge

risks calls for new products but also leads

to new forms of uncertainty (eg counterparty risk, systemic risk).

Fraud is as much a displacement in legal

standards as the consequence of attempts

to circumvent those standards. Inversely,

in a grey area marked by a change in the

linkage between information provided and

trust, fraud is what happens to a codied

area in which existing rules and standards

have become obsolete. The crisis is especially a moral moment, with a coming

of awareness, when losses are revealed.

Fraud therefore expresses a need for standards that is revealed after the event by a

crisis. It also reveals market ineciency

because prices are distorted: a player with

too much power can distort prices

which could qualify as fraud, potentially

justifying taking measures against a monopoly.

In the end, the issue is how the lender of

last resort responds to fraud and the eventuality of accommodating fraud in containing the crisis. This situation of moral

hazard is extremely sensitive, because it

suggests an arbitrage between crisis and

fraud when things have gone too far, and

raises a thorny ethical question. But that is

another story with a plot that thickens

after the crisis.

REFERENCES

(1) This paper is heavily indebted to Kindleberger, C. P. (2000) Manias, panics and

crashes: A history of nancial crises, John

Wiley & Sons, Inc. 4th ed., especially Ch.

5 The emergence of swindles.

(2) Kindleberger (2000) op. cit., p. 3.

(3) Plautus, Miles Gloriosus, 2.2.9.

(4) Cicero, Oration for Titus Annius Milo,

XII.

(5) Kindleberger (2000) op. cit., p. 74.

(6) Ibid., p. 74.

(7)

(8)

(9)

(10)

(11)

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

(16)

(17)

(18)

(19)

(20)

(21)

Ibid., p. 88.

Thiveaud, J. M. (1996) La conance souveraine, in Rapport moral sur largent

dans le monde, Association de conomie

nancie`re, Montchrestien, Paris, pp. 407

417.

Cicero, De Ociis, II, 84.

Kindleberger (2000) op. cit., p. 77. Literature provides a wealth of fraud-related

themes. This is particularly true in

Balzacs Melmoth reconcilie and La

Maison Nucingen, and in Zolas novel

LArgent which is based on Euge`ne

Bontoux and the Union Generale. (Kindleberger (2000) op. cit., p. 81).

See eg Becker, G. S. (1968) Crime and

Punishment: An Economic Approach,

Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 76, pp.

169217, or, Becker, G. S. and Landes,

W. M. (1974) Essays in the economics of

crime and punishment, Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of

Economic Research, New York.

Kindleberger (2000) op. cit., p. 77.

Ibid., pp. 7879.

Ibid., p. 80.

Ibid., pp. 80, 85.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1989) Manias, panics

and crashes: A history of nancial crises,

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2nd edition, p.

103.

Kindleberger (2000) op. cit., p. 78.

Ibid., p. 81, quoting Edvard Lasker.

Ibid., p. 89.

Ibid.

Source: Caprio and Kingebiel, Bank

insolvency: Bad luck, bad policy, or bad

banking? in Bruno, M. and Pleskovic, B.

(eds) Annual World Bank Conference on

Development Economics 1996, World

Bank, Washington, DC.

FURTHER READING

Akerlof, G. A. and Romer, P. M. (1993)

Looting: The economic underworld of

bankruptcy for prot, Brookings Papers

on Economic Activity.

Balzac, Honore de Melmoth Reconcilie and

La Maison Nucingen.

Benston, G. A., Carhill, M. and Olasov, B.

(1991) The failure and survival of thrifts,

Page 69

Crisis and fraud

in Hubbard, R. G. (ed.) Financial

markets and nancial crises?, University

of Chicago Press.

Bouvier, J. (1960) Le Krach de lUnion

Generale, PUF, Paris.

Carswell, J. (1960) The South Sea Bubble,

Crosset, London.

Donnard, J. H. (1961) Balzac, les realites

economiques and sociales dans la

Comedie Humaine, Colin, Paris, chapters

Crises, fraudes et faillites and Speculation.

French Senate Report (19992000) Pour un

nouvel ordre nancier mondial: responsabilite, ethique, ecacite.

Page 70

Kane, E. J. (1989) The Savings and Loans

insurance mess: How did it happen?,

Urban Press, Washington DC.

Lewin, H. G. (1968) The railway mania and its

aftermath, 18451852, Augustus M.

Kelley, New York.

Van Vlek, G. W. (1943) The panic of 1857:

An analytical study, Columbia University Press, New York.

Washburn, W. and Delong, E. S. (1932) High

and low nanciers: Some notorious

swindlers and their abuses of our modern

stock selling system, Bobbs-Merrill,

Indianapolis.

Zola, Emile LArgent.

You might also like

- Pre-Algebra Homework BookDocument218 pagesPre-Algebra Homework BookRuben Pulumbarit III100% (12)

- Ank Otes: Confusing Capitalism With Fractional Reserve BankingDocument11 pagesAnk Otes: Confusing Capitalism With Fractional Reserve BankingMichael HeidbrinkNo ratings yet

- Money CreationDocument6 pagesMoney CreationYoucef GrimesNo ratings yet

- Countering Illicit and Unregulated Money FlowsDocument40 pagesCountering Illicit and Unregulated Money FlowstblickNo ratings yet

- Genmath Week 11 20Document20 pagesGenmath Week 11 20Kenneth Figueroa100% (1)

- Anti Corruption BookDocument84 pagesAnti Corruption BookChris Ogola100% (1)

- Chapter 4:fraud For ThoughtDocument42 pagesChapter 4:fraud For Thoughtdrb@erols.com100% (1)

- Kindle BergerDocument13 pagesKindle BergerABBBANo ratings yet

- Financial Markets and Institutions: Ninth EditionDocument35 pagesFinancial Markets and Institutions: Ninth EditionمريمالرئيسيNo ratings yet

- Brooks - AQR Drivers of Bond YieldsDocument27 pagesBrooks - AQR Drivers of Bond YieldsStephen LinNo ratings yet

- The AML Compliance Book - 150 Go - Matis MaekerDocument189 pagesThe AML Compliance Book - 150 Go - Matis Maekerbalup123No ratings yet

- Chapter 10, Question 1. ADocument22 pagesChapter 10, Question 1. ANeldybanik100% (2)

- 10 Myths About Financial DerivativesDocument13 pages10 Myths About Financial DerivativesNatalia Gutierrez FrancoNo ratings yet

- FORECLOSE ON THE FRAUDSTERS - PUT BANK OF AMERICA IN RECEIVERSHIP - White Collar Expert Calls For FDIC To Take Control of BofADocument8 pagesFORECLOSE ON THE FRAUDSTERS - PUT BANK OF AMERICA IN RECEIVERSHIP - White Collar Expert Calls For FDIC To Take Control of BofA83jjmack100% (2)

- Issues in Commodity FinanceDocument23 pagesIssues in Commodity FinancevinaymathewNo ratings yet

- Sources of Finance: Ib Business & Management A Course Companion (2009) P146-157 (Clark Edition)Document54 pagesSources of Finance: Ib Business & Management A Course Companion (2009) P146-157 (Clark Edition)sshyamsunder100% (1)

- Promoting Integrity in the Work of International Organisations: Minimising Fraud and Corruption in ProjectsFrom EverandPromoting Integrity in the Work of International Organisations: Minimising Fraud and Corruption in ProjectsNo ratings yet

- Money Laundering: A Concise Guide For All BusinessDocument6 pagesMoney Laundering: A Concise Guide For All BusinessYohanes Eka WibawaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Money LaunderingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Money Launderingefhs1rd0No ratings yet

- ReflectionsOnFinanceAndTheGoodSoci PreviewDocument9 pagesReflectionsOnFinanceAndTheGoodSoci PreviewWalter ArceNo ratings yet

- Imf Anti Money Laundering and Economic Stability StraightDocument2 pagesImf Anti Money Laundering and Economic Stability StraightmattytwatcherNo ratings yet

- 2021 Corruption and Economic Crime - FinalDocument17 pages2021 Corruption and Economic Crime - FinalDallandyshe RrapollariNo ratings yet

- Mcclellan 241111 V 2Document34 pagesMcclellan 241111 V 2tonyp99No ratings yet

- 23 - ML Typologies - A Review of Their Fitness For PurposeDocument50 pages23 - ML Typologies - A Review of Their Fitness For Purpose1 2No ratings yet

- A Compilation of Individual Report: S.Y. 2018 - 2019 1 SemesterDocument6 pagesA Compilation of Individual Report: S.Y. 2018 - 2019 1 SemesterHardworkNo ratings yet

- Global Perspective of Financial CrimesDocument7 pagesGlobal Perspective of Financial Crimesrakibul islamNo ratings yet

- RK&S Smart Solutions, Inc.: Risk ManagementDocument6 pagesRK&S Smart Solutions, Inc.: Risk ManagementantishrillwebdesignNo ratings yet

- How Economic crimes pose significant challenges to individuals, businesses, government and societies worldwide?Document4 pagesHow Economic crimes pose significant challenges to individuals, businesses, government and societies worldwide?Charm HernandezNo ratings yet

- Money LaunderingDocument88 pagesMoney LaunderingAhmad GhoziNo ratings yet

- Derivatives Myths and RealitiesDocument7 pagesDerivatives Myths and RealitiesPratik KillaNo ratings yet

- Isk Instruments in The Medieval and Early Modern Economy: Meir KohnDocument20 pagesIsk Instruments in The Medieval and Early Modern Economy: Meir Kohnleomer7697No ratings yet

- White Collar Crime Profile and Prevention ResponsibilitiesDocument31 pagesWhite Collar Crime Profile and Prevention ResponsibilitiesAakash TiwariNo ratings yet

- Money Laundering Essay ThesisDocument4 pagesMoney Laundering Essay Thesissararousesyracuse100% (2)

- Corruption and Economic Crime Share Common Characteristics and DriversDocument18 pagesCorruption and Economic Crime Share Common Characteristics and DriverssaraNo ratings yet

- 10 Myths About Financial DerivativesDocument6 pages10 Myths About Financial DerivativesArshad FahoumNo ratings yet

- Economic & Moral Impact of CorruptionDocument13 pagesEconomic & Moral Impact of CorruptionMark Regan100% (2)

- CindoriDocument18 pagesCindoriAnushanNo ratings yet

- IMF_Lagarde_Speech_27.5.14Document7 pagesIMF_Lagarde_Speech_27.5.14EDHUARD JHEANPIERD VILCAHUAMAN ILIZARBENo ratings yet

- Faith in The Numbers 9-4robertsDocument9 pagesFaith in The Numbers 9-4robertsDuarte Rosa FilhoNo ratings yet

- Money Laundering With DerivativesDocument8 pagesMoney Laundering With DerivativesYan YanNo ratings yet

- Scott Bader-Saye - Islamic Banking, Microfinance, Monte Di Pieta!Document21 pagesScott Bader-Saye - Islamic Banking, Microfinance, Monte Di Pieta!Rh2223dbNo ratings yet

- Forensic Accounting A Tool of Detecting White Collar Crimes in Corporate World - February - 2012 - 9666595134 - 9500165Document3 pagesForensic Accounting A Tool of Detecting White Collar Crimes in Corporate World - February - 2012 - 9666595134 - 9500165Mukund ChawdaNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Money LaunderingDocument8 pagesPHD Thesis On Money Launderingdwsmjsqy100% (2)

- Book Review of The Grip Of Death on Debt Slavery and Destructive EconomicsDocument4 pagesBook Review of The Grip Of Death on Debt Slavery and Destructive EconomicsLuiz CorleoneNo ratings yet

- The Cost of CorruptionDocument33 pagesThe Cost of CorruptionMiri ChNo ratings yet

- Bfcsa Submission To ParliamentDocument72 pagesBfcsa Submission To ParliamentInspector McTaggart's Crime SeriesNo ratings yet

- Fcic Final Report ConclusionsDocument14 pagesFcic Final Report ConclusionsTiffany L. ArthurNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Money LaunderingDocument4 pagesResearch Paper About Money Launderingafnhcikzzncojo100% (1)

- Managing Country Risk in an Age of Globalization: A Practical Guide to Overcoming Challenges in a Complex WorldFrom EverandManaging Country Risk in an Age of Globalization: A Practical Guide to Overcoming Challenges in a Complex WorldNo ratings yet

- Ponzi Scheme Paper1Document4 pagesPonzi Scheme Paper1Junius Markov OlivierNo ratings yet

- Chasing Dirty Money: Evaluating the Global Anti-Money Laundering RegimeDocument8 pagesChasing Dirty Money: Evaluating the Global Anti-Money Laundering RegimeManuel LozadaNo ratings yet

- Political Fallouts and Resignations: A Deep Dive Into Financial ScandalsFrom EverandPolitical Fallouts and Resignations: A Deep Dive Into Financial ScandalsNo ratings yet

- Factiva 20190909 2242Document4 pagesFactiva 20190909 2242Jiajun YangNo ratings yet

- Wall Street Lies Blame Victims To Avoid ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesWall Street Lies Blame Victims To Avoid ResponsibilityTA WebsterNo ratings yet

- Trade and Payments Theory in A Financialized Economy Michael HudsonDocument13 pagesTrade and Payments Theory in A Financialized Economy Michael Hudsonkukuman1234No ratings yet

- PT AdiDocument3 pagesPT AdiLiana MoisescuNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00Document74 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00skywardsword43No ratings yet

- Business Crime and TypesDocument7 pagesBusiness Crime and TypesSivan JacksonNo ratings yet

- Countering Illicit Money FlowsDocument40 pagesCountering Illicit Money FlowsDiana María Peña GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Anti Money LaunderingDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Anti Money Launderingtwdhopwgf100% (1)

- Canada LawDocument9 pagesCanada LawCAJES NOLINo ratings yet

- The Origins and Evolution of Credit Risk Management: RiskhistoryDocument3 pagesThe Origins and Evolution of Credit Risk Management: RiskhistoryjayaNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Corruption and Money Laundering DefinedDocument5 pagesConcepts of Corruption and Money Laundering DefinedThomas T.R HokoNo ratings yet

- Reinventing Banking: Capitalizing On CrisisDocument28 pagesReinventing Banking: Capitalizing On Crisisworrl samNo ratings yet

- Chapter - I Enterprise Risk Management: An IntroductionDocument37 pagesChapter - I Enterprise Risk Management: An IntroductionkshitijsaxenaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Comprehensive Performance Measurement Systems On Role Clarity Psychological Empowerment and Managerial Performance 2008 Accounting OrganDocument23 pagesThe Effect of Comprehensive Performance Measurement Systems On Role Clarity Psychological Empowerment and Managerial Performance 2008 Accounting OrganLilian BrodescoNo ratings yet

- Cultural Dynamics of Corporate Fraud: The AuthorDocument15 pagesCultural Dynamics of Corporate Fraud: The AuthormadaharimNo ratings yet

- Governance Good Corporate Practices in Poor Corporate Governance SystemsDocument2 pagesGovernance Good Corporate Practices in Poor Corporate Governance SystemsmadaharimNo ratings yet

- APA Citation Style Examples For UWA 080514 PDFDocument11 pagesAPA Citation Style Examples For UWA 080514 PDFPrasanna KumarNo ratings yet

- A: Economic and Business Cycles GDP Expenditure ApproachDocument57 pagesA: Economic and Business Cycles GDP Expenditure ApproachPavan LuckyNo ratings yet

- Black Book On Investment of Working WomenDocument88 pagesBlack Book On Investment of Working WomenRizwan Shaikh 44100% (2)

- Chapter 05 Testbank QuestionsDocument38 pagesChapter 05 Testbank QuestionsTu NgNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Lieu of 2nd Internal-FT-IV (E F G) - BFSDocument2 pagesAssignment in Lieu of 2nd Internal-FT-IV (E F G) - BFSSiddhesh ShahNo ratings yet

- Busn 9th Edition Kelly Test BankDocument10 pagesBusn 9th Edition Kelly Test BankDarinFreemantqjn100% (69)

- University of Saint LouisDocument3 pagesUniversity of Saint LouisRommel RoyceNo ratings yet

- Loan FeesDocument19 pagesLoan FeesAries BautistaNo ratings yet

- Sacco Times Issue 025 Final PrintDocument48 pagesSacco Times Issue 025 Final PrintSATIMES EAST AFRICANo ratings yet

- Basic Finance Mathematics Business FinanceDocument16 pagesBasic Finance Mathematics Business FinanceOshoba MayowaNo ratings yet

- Financial Derivatives: Prof. Scott JoslinDocument44 pagesFinancial Derivatives: Prof. Scott JoslinarnavNo ratings yet

- Combine Mat112Document160 pagesCombine Mat112Misha AfezaNo ratings yet

- FIN221 Chapter 3Document45 pagesFIN221 Chapter 3jojojoNo ratings yet

- MGT201 Midterm Solved 8 Papers Quisses by Ali KhannDocument74 pagesMGT201 Midterm Solved 8 Papers Quisses by Ali KhannmaryamNo ratings yet

- Examination of Monetary Policy and Financial Performance of Deposit Money Bank in NigeriaDocument71 pagesExamination of Monetary Policy and Financial Performance of Deposit Money Bank in NigeriaDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- ECF5923 MACROECONOMICS Study NotesDocument24 pagesECF5923 MACROECONOMICS Study NotesLiamNo ratings yet

- DraftDocument2 pagesDraftYUDITA NUR'AININNo ratings yet

- ECO531 Chapter 2 Mind MapDocument6 pagesECO531 Chapter 2 Mind MapASMA HANANI BINTI ANUAR100% (1)

- Ch05 Mini Case DisneyDocument8 pagesCh05 Mini Case DisneyRahil VermaNo ratings yet

- AgreementForm10045975 29-8-2023 113636Document33 pagesAgreementForm10045975 29-8-2023 113636greenrootfinancialservicesNo ratings yet

- 9.2 - Compounding at Intervals Less Than 1 YearDocument8 pages9.2 - Compounding at Intervals Less Than 1 YearKarim GhaddarNo ratings yet

- Measuring and Evaluating The Performance of Banks and Their Principal CompetitorsDocument46 pagesMeasuring and Evaluating The Performance of Banks and Their Principal CompetitorsyeehawwwwNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1: Risk ManagementDocument49 pagesChapter - 1: Risk Managementbeena antuNo ratings yet

- AP Macroeconomics: Sample Student Responses and Scoring CommentaryDocument6 pagesAP Macroeconomics: Sample Student Responses and Scoring CommentaryDion Masayon BanquiaoNo ratings yet