Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Relation Between Somatization and Outcome

Uploaded by

Adina Bîrsan-MarianCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Relation Between Somatization and Outcome

Uploaded by

Adina Bîrsan-MarianCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613 620

The relationship between somatisation and outcome in patients

with severe irritable bowel syndrome,

Francis Creed a,,1 , Barbara Tomenson a,1 , Elspeth Guthrie a,1 , Joy Ratcliffe a ,

Lakshmi Fernandes c,1 , Nicholas Read c,1 , Steve Palmer d , David G. Thompson b,1

a

Division of Psychiatry, University of Manchester

Section of Gastrointestinal Science, University of Manchester

c

Centre for Human Nutrition, Northern General Hospital, University of Sheffield

d

Centre for Health Economics, University of York

b

Received 5 September 2007; received in revised form 18 February 2008; accepted 18 February 2008

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to assess the relationship between

somatisation and outcome in patients with severe irritable bowel

syndrome (IBS). Method: Two hundred fifty-seven patients with

severe IBS included in a randomised controlled trial were assessed

at baseline and divided into four quartiles on the basis of their

somatisation score. The patients were randomised to receive the

following over 3 months: brief interpersonal psychotherapy, 20 mg

daily of the SSRI antidepressant paroxetine, or treatment as usual.

Outcome 1 year after treatment was assessed using the Short Form36 physical component summary (PCS) score and total costs for

posttreatment year. Results: The patients in the quartile with the

highest baseline somatisation score had the most severe IBS, the

most concurrent psychiatric disorders, and the highest total costs

for the year prior to baseline. At 1 year after the end of treatment,

however, the patients with marked somatisation, who received

psychotherapy or antidepressant, had improved health status

compared to those who received usual care: mean (S.E.) PCS

scores at 15 months were 36.6 (2.2), 35.5 (1.9), and 26.4 (2.7) for

psychotherapy, antidepressant, and treatment-as-usual groups,

respectively (adjusted P=.014). Corresponding data for total costs

over the year following the trial, adjusted for baseline costs, were

1092 (487), 1394 (443), and 2949 (593) (adjusted P=.050).

Conclusions: Patients with severe IBS who have marked

somatisation improve with treatment like other IBS patients and

show a greater reduction of costs. Antidepressants and psychotherapy are cost-effective treatments in severe IBS accompanied by

marked somatisation.

2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome; Outcome; Health-related quality of life; Somatisation; Antidepressants; Psychotherapy

Disclosure: F. Creed has consultancy links with Lilly. He has received

payment for sitting on an advisory panel. All other authors declare that they

have no competing interests.

Grant support: Medical Research Council (MRC) Grant No.

G9413613 and UK North West Regional Health Authority Research and

Development Directorate.

Corresponding author. Psychiatry Research Group, Medical School,

University of Manchester, Rawnsley Building, Oxford Road, M13 9WL

Manchester, UK. Tel.: +44 0161 276 5331/5395; fax: +44 0161 273 2135.

1

On behalf of the North of England IBS Research Group: Chris Babbs,

Joe Barlow, Chandu Bardhan, Francis Creed, David Dawson, Lakshmi

Fernandes, Elspeth Guthrie, Stephanie Howlett, Linda McGowan, Jane

Martin, Jim Moorey, Kierran Moriarty, Stephen Palmer, Joy Ratcliffe,

Nicholas Read, Christine Rigby, Irene Sadowski, David Thompson, and

Barbara Tomenson.

E-mail address: francis.creed@manchester.ac.uk (F. Creed).

0022-3999/08/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.016

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common disorder,

which forms the major reason for referral to gastroenterology clinics and often leads to impaired health-related

quality of life and high health care and societal costs [1,2].

Depressive and anxiety disorders commonly coexist with

IBS [2,3] and a history of sexual abuse is common [2];

these all contribute to poor outcomes [2,46]. In addition,

some IBS patients report numerous bodily symptoms,

known either as somatisation or as extraintestinal IBS

symptoms [3]. Nearly half of IBS patients attending a

tertiary referral clinic have somatisation disorder or border

614

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

on this diagnosis [7,8]. Such somatisation is associated

with other psychiatric disorders (e.g., anxiety and depressive disorders), marked impairment of functioning, and

high health care use [7,911].

Psychological treatment and antidepressants have been

used to treat IBS [1218], and when patients improve, there

may be a reduction in somatisation score [1923], especially

if there is a history of sexual abuse [4], but no previous study

has examined how IBS patients with somatisation respond to

treatment with psychotherapy or antidepressants.

In a recent randomised controlled trial, we found that both

psychodynamic interpersonal therapy and an SSRI antidepressant led to improved health status in patients who had

severe IBS [24]. This improvement was not obviously

related to concurrent anxiety or depressive disorder but was

related to somatisation score [25]. In view of this finding, we

report here a further analysis of our trial data to examine

whether patients with a high baseline somatisation score

improved in health status and total costs following treatment.

We tested the hypothesis that patients with a high

somatisation score would show less improvement in health

status than those with low somatisation scores when treated

with psychotherapy or an SSRI antidepressant. Since we did

not measure somatisation disorder, we divided our sample of

IBS patients into groups according to baseline SCL-90

somatisation score, as others have done previously [9,26],

and compared these groups in terms of other baseline

variables and response to treatment. In order to specify the

importance of somatisation, we controlled for the effect of

depression, anxiety, and sexual abuse history.

Method

Participants were recruited from patients attending seven

gastroenterology clinics in UK. All clinic patients who

fulfilled Rome I criteria for IBS [27] and whose symptoms

had not responded to usual medical treatment were invited

to join the trial. This involved random allocation to eight

sessions of individual psychotherapy, 3 months of treatment

with 20 mg daily of the SSRI antidepressant paroxetine, or

routine care by a gastroenterologist and a general practitioner

[24]. Patients were excluded if they had a psychotic disorder,

a severe personality disorder, or an active suicidal ideation or

if they had consumed more than 50 units of alcohol per

week, but patients with other psychiatric disorders were

included. Patients were recruited by gastroenterologists and

first assessed by researchers in the gastroenterology clinic.

Assessments reported here were made at baseline (entry

to the trial) and 12 months after treatment was completed

(i.e., 15 months after baseline). Full details of the trial have

been reported previously, including the CONSORT details,

and will not be repeated here [24].

The following self-administered questionnaires were

completed by each patient at baseline and at 15 months

follow-up. Severity of current abdominal pain was assessed

using a visual analogue scale (VAS) taken from the McGill

Pain Questionnaire [28]. Somatisation was measured using

the SCL-90 questionnaire, and the somatisation subscale was

used in this study [29]. A history of sexual abuse was

documented using the Drossman questionnaire [30]. In this

report, sexual abuse refers to being forced to have sexual

contact against one's will either as a child or as an adult.

Health status was measured using the Short Form-36 (SF-36)

[31], which corresponds closely to patients' rating of the

degree to which it disrupts their daily lives [32,33]. We used

the physical component summary (PCS) score as the main

outcome variable [34]. This is a composite score of the

following scales: physical function, role limitation physical,

bodily pain, and health perception; a low score indicates poor

health status.

A trained psychiatrist who worked independent of

treating clinicians and was blind to treatment group

assessed severity of depressive symptoms using the

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [35]. This psychiatrist also assessed psychiatric diagnosis at baseline only

using the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) [36].

Total costs were calculated using the following: (a) Direct

health care costs derived by applying an appropriate unit cost

to each recorded contact or episode of care. These contacts

were taken directly from the patient's hospital and primary

care notes because all patients received professional health

care solely from the U.K. National Health Service [24]. This

included inpatient days, all other hospital attendances, all

primary care contacts, domiciliary care services, and

prescribed medications plus alternative therapies. (b) Direct

non-health care costs, namely, travel and additional patient

expenditure as a result of the illness including nonprescription medication. (c) Productivity costs measured by applying

the patient's wage rate to the number of days lost due to

either illness or clinic attendance. Data are presented for two

time periods: 12 months prior to baseline and 12 months after

the end of treatment.

The trial was designed with abdominal pain, SF-36

physical component scores (health status), and costs as

primary outcome variables as they measure different

domains [24]. The trial was powered (85 patients in each

group) on improvement in abdominal pain found in our

previous trial [37]. There was no prior power calculation for

the present study. Ethics committee approval was obtained

from each hospital taking part in the study, and all

participants signed written informed consent after full

explanation prior to entering the study.

Data analysis

All data were entered and analysed on SPSS, version

13.5. We divided the sample into four quartiles on the

basis of baseline somatisation score and compared these

in terms of sociodemographic variables and other baseline

variables using chi-square or one-way analysis of

variance tests for linear trend. We then compared the

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

outcome scores by treatment group (psychotherapy,

antidepressant, and treatment as usual) for each quartile

to assess whether the beneficial effect of treatment

recorded for the whole trial was found in one quartile

or more. This was an intention-to-treat analysis and

included all patients, whether or not they had adhered to

the treatment to which they had been allocated. Analysis

of SF-36 physical component score at 15 months followup (i.e., 1 year after the end of treatment) used ANCOVA

with the following as covariates: age, sex, baseline

physical component score, years of education, Hamilton

depression score, panic and generalised anxiety disorders,

and abuse history. The analysis of costs used total costs

for the year following treatment as the outcome with the

same list of covariates except for the fact that total costs

for the year prior to trial baseline was used instead of

baseline PCS score.

615

Results

Two hundred fifty-seven participants (81% of eligible

patients) were recruited to the study. The 60 patients who

declined to enter the study were similar in baseline characteristics to the participants. The IBS was chronic (median duration,

8 years) and severe (mean typical pain score was 67.4 out of

100). Seventy (27%) participants were unemployed as a result of

illness, and 121 (47%) had a psychiatric disorder, principally

depressive disorder (29%), panic disorder (12%), generalised

anxiety disorder (14%), and neurasthenia (35%) [6]. Of the 257

patients, follow-up data 1 year after treatment were available for

225 patients (87.5%) and data on total costs were available for

249 patients (97%). The patients for whom there were no

follow-up data on SF-36 PCS were significantly younger than

the remainder but not significantly different in terms of sex,

SF-36 PCS score, and SCL-90 somatisation score.

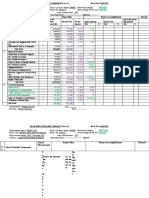

Table 1

Comparison of the four quartiles according to baseline somatisation scores (1 being the lowest and 4 being the highest)

Quartile according to somatisation score a

1 (00.5),

n=57

Demographic data

Female

Marital status

Single

Married/Cohabiting

Separated/

Divorced/Widowed

White Caucasian

12 years of

education (or more)

Unemployed due

to ill-health

Sexual abuse

None

Forced touching

Rape

SCAN diagnosis

Depression

Panic disorder

Hypochondriasis

Neurasthenia

Generalised

anxiety disorder

Rome diagnosis

General

Diarrhea

Constipation

2 (0.510.99),

n=69

3 (1.01.49),

n=60

4 (1.54.0),

n=65

P value

b

43

75

62

90

48

80

47

72

1.0

8

40

9

14

70

16

18

40

11

26

58

16

13

41

6

22

68

10

11

42

12

17

65

18

5.1

.53

55

39

96

68

67

40

97

58

60

35

100

58

65

23

100

35

3.5 b

12.3 b

.061

b.001

13

23

10

14

11

18

34

52

14.8 b

b.001

48

5

4

84

9

7

53

7

9

77

10

13

47

7

6

78

12

10

44

9

12

68

14

18

4.0 b

.045

9

1

3

16

5

16

2

5

28

9

13

5

5

17

8

19

7

7

25

12

20

5

2

21

11

33

8

3

21

18

32

18

11

34

11

49

28

17

52

17

20.0 b

19.3 b

4.1 b

9.9 b

2.4

b.001

b.001

.042

.002

.12

20

21

16

35

37

28

40

16

12

58

25

17

32

12

16

53

20

27

30

22

13

46

34

20

9.8

.13

.32

Continuous variables at baseline

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

P value

Age (years)

Mean total costs

(UK ) for 1 year

prior to baseline

38.3

1027

1.6

164

39.1

1168

1.5

166

39.6

976

1.6

109

42.6

2058

1.3

329

.048

.001

a

b

Six subjects do not belong to any of the four somatisation groups because they did not complete the SCL-90 at baseline.

2 test for linear trend across the four somatisation groups.

616

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

In the 3-month treatment period, 59 of 85 (69%) patients

randomised to psychotherapy completed all eight sessions

whereas 43 of 86 (50%) patients randomised to paroxetine

completed the 12-week course (P=.013). At follow-up (15

months after baseline), there was no difference between

the three random allocation groups on abdominal pain

severity, but SF-36 physical component score had

improved for both psychotherapy and paroxetine groups

compared to the treatment-as-usual group, and this was

achieved at no additional cost [24]. The higher costs for 3

months of psychotherapy and paroxetine were offset by

lower costs in the subsequent year; hence, the mean health

care costs for the whole period from baseline to 1 year

after the end of treatment, adjusted for baseline costs, were

683 (S.E.=144), 789 (S.E.=138), and 970 (S.E.=141)

for psychotherapy, antidepressants, and treatment as usual,

respectively (P=.36) [24].

Baseline data four quartiles according to somatisation

Somatisation data were available at baseline for 251

patients; the mean SCL-90 somatisation score was 1.12

(S.D.=0.76, range=03.9). The 251 patients were divided

into four quartiles according to baseline SCL-90 somatisation scores: 00.5 (n=57), 0.510.99 (n=69), 1.01.49

(n=60), and 1.54.0 (n=65). The mean (S.D.) number of

somatic symptoms endorsed as moderately bothersome or

worse on the SCL-90 questionnaire (maximum of 12) was

0.7 (0.7), 2.4 (1.0), 4.1 (1.0), and 8.0 (2.2) for the four

quartiles, respectively. The most common symptoms were

the following: headaches, faintness or dizziness, pain in

lower back, soreness of muscles, trouble getting one's

breath, hot or cold spells, numbness or tingling in certain

parts of the body, feeling weak in certain parts of the body,

and heavy feeling in arms or legs.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the four quartiles

are shown in Table 1. The patients from the quartile with the

highest somatisation score were older, were more likely to be

unemployed due to ill-health, and had received fewer years

of education than the other groups. These patients with high

somatisation scores also had more marked IBS symptoms

(abdominal pain and severity score on a daily diary)

(Table 2), but there was no difference according to Rome

diagnosis. All psychiatric diagnoses, except generalised

Fig. 1. SF-36 PCS scores at 1 year after the end of treatment, by treatment

group for the four quartiles according to baseline somatisation score, are

shown. Follow-up PCS score was adjusted for age, sex, years of education,

depression, panic and generalised anxiety disorders, abuse history, and

baseline SF-36 physical component score.

anxiety disorder, were more common in the quartile with the

highest somatisation scores (Table 1).

The quartile with the highest somatisation score also had

the lowest SF-36 physical component scores, indicating

greatest impairment of health status (Table 2). The total costs

for 1 year before baseline were greatest in this quartile with a

high somatisation score (Table 1, bottom row).

Outcome at follow-up 1 year after the end of treatment by

somatisation quartile

There was no difference between the four somatisation

quartiles in the proportion who adhered to the course of

treatment to which they were randomised: 82.5%, 81.2%,

76.7%, and 73.8% of each quartile received four or more

sessions of psychotherapy or 6 weeks of antidepressant

treatment. At follow-up, 1 year after the end of treatment, the

mean SF-36 physical component scores (adjusted for

baseline score) were no longer significantly different across

the four somatisation quartiles. This occurred because the

SF-36 physical component score in the quartiles with a high

somatisation score had improved by 7 points (from 31.1 to

38.1, Table 2 bottom row). Abdominal pain scores and

symptom diary scores were also not significantly different

between the four quartiles at follow-up as the patients in the

quartile with the highest somatisation score had improved

Table 2

Scores for IBS symptoms, depression, and SF-36 (health status) at baseline and at follow-up 1 year after the end of treatment (in italics)

Baseline and follow-up values

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

VAS score for abdominal pain (maximum, 100)

VAS score for abdominal pain at 1 year follow-up

IBS symptom severity (composite diary score)

IBS symptom severity at 1 year follow-up

Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression score

Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression score at 1 year follow-up

SF-36 physical component score

SF-36 physical component score at 1 year follow-up

26.1

30.2

1.47

1.35

7.8

7.3

42.4

41.7

3.2

3.9

0.09

0.1

0.8

0.8

1.3

1.5

31.7

27.1

1.51

1.38

10.0

6.8

40.2

42.3

2.9

3.3

0.08

0.1

0.6

0.7

1.2

1.2

34.9

32.8

1.66

1.44

12.2

6.5

37.4

40.9

3.1

3.6

0.08

0.1

0.7

0.8

1.4

1.3

47.8

33.3

2.07

1.58

15.1

11.9

31.1

38.1

3.0

3.6

0.08

0.1

0.8

0.8

1.1

1.3

b.001

.58

b.001

.36

b.001

b.001

b.001

.13

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

617

Table 3

Change in SF-36 physical component score (mean and S.E.) by treatment group according to somatisation quartile (1 being the lowest and 4 being the highest)

1 (00.5), n=39

2 (0.510.99), n=58

3 (1.01.49), n=46

4 (1.54.0), n=49

Somatisation group

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Mean

S.E.

Psychotherapy

Antidepressants

Treatment as usual

P value for comparison between treatment groups

3.8 (n=12)

3.3 (n=10)

2.4 (n=17)

.89

2.4

2.6

2.0

6.7 (n=20)

5.2 (n=20)

1.7 (n=18)

.14

1.7

1.7

1.8

3.7 (n=11)

6.7 (n=20)

0.79 (n=15)

.12

2.9

2.2

2.6

6.9 (n=16)

4.4 (n=22)

5.0 (n=11)

.009

2.2

1.9

2.8

Scores were adjusted for age, sex, years of education, depression, panic and generalised anxiety disorders, abuse history, and baseline PCS score.

considerably (Table 2). Depression scores had dropped but

were still significantly different across the groups.

Outcome by treatment group and by somatisation quartile

Health status

The differences according to treatment group are shown

in Fig. 1. In the quartile with the highest baseline

somatisation score, the psychotherapy and antidepressant

groups had higher (i.e., less impaired) SF-36 physical

component scores at follow-up than the treatment-as-usual

group (right-hand columns in Fig. 1). The change in SF-36

physical component score between baseline and 15 months

follow-up is shown in Table 3. It can be seen that the

improvement after treatment in the quartile with the highest

somatisation score is comparable with the other quartiles, but

in this quartile, the significant difference between treatment

groups is explained by the worsening of the treatment-asusual group.

Costs

The total costs for the year after treatment ended are

shown in Fig. 2. A difference between treatment groups is

apparent only in the quartile with the highest somatisation

score. In this quartile, the mean total costs were reduced in

the posttreatment year compared to the year before baseline

for the psychotherapy and antidepressant groups but

remained high in the treatment-as-usual group. Total costs

over the year following the end of treatment, adjusted for

baseline costs, were 1092 (487), 1394 (443), and 2949

(593) for the psychotherapy, antidepressant, and treatmentas-usual groups, respectively (adjusted P=.050).

somatisation score did poorly with treatment as usual

physical component scores deteriorated by a clinically

significant amount (5 points) in this group, and the total

costs incurred in this group remained very high. By contrast,

the patients with a high somatisation score who received

psychotherapy or paroxetine showed an improvement in

their physical component score by a clinically significant

amount and a reduction in total costs of ca. 50% compared to

pretrial levels. We had not expected this result as patients

with marked somatisation are generally considered to be the

least likely to improve.

In this study, we did not assess somatisation disorder

as such. It is notable, however, that the quartiles with a

low somatisation score reported only a few bodily

symptoms, indicating that these patients did not have

somatisation disorder, which is defined by multiple bodily

symptoms. By contrast, the quartile with the highest

somatisation score reported a mean of eight different

bothersome bodily symptoms, which is compatible with

the previous result that 25% of tertiary clinic IBS patients

had somatisation disorder. Patients from this top quartile

were more likely than those from the other quartiles to

have other psychiatric disorders (depressive disorder,

panic disorder, and neurasthenia) and to incur high health

care and total costs and were more impaired in line with

the previous findings.

Discussion

The main new finding in this study is the fact that our

hypothesis was not confirmed; patients with a high

somatisation score responded to psychotherapy or antidepressant treatment like other patients who had a lower

somatisation score. In fact, it was only in the quartile with the

highest somatisation score that the improvement in SF-36

physical component score was significantly different, with

greater improvement in the psychotherapy and paroxetine

groups than in the treatment-as-usual group. This result

could be explained by the fact that patients with a high

Fig. 2. Total costs for 1 year (geometric means) after treatment ended, by

treatment group for the four quartiles according to baseline somatisation

score, are shown. Total costs were adjusted for age, sex, years of education,

depression, panic and generalised anxiety disorders, abuse history, and

baseline costs (12 months before baseline).

618

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

Like Kroenke et al. [26], we found that dividing our

sample into four groups according to somatisation score

shows a doseresponse relationship with health status,

which was markedly impaired in our quartile with the

highest somatisation score [nearly two standard deviations

below the population norm (of 50, S.D.=10)]. The pattern

of costs differed from the dose response reported by

Spiegel et al. [9], which can be explained by the fact that

our inclusion criteria meant that all our participants had

rather high costs whereas Spiegel's sample included many

with very low costs. The high costs in our sample contrast

with the low costs for IBS patients in primary care [38]. It

is likely that patients with IBS and a high somatisation

score are mostly seen in secondary care clinics, and this

may be why psychological treatments for IBS have been

found to be more effective in secondary care than primary

care it is only in the more severe IBS that a significant

difference can be found between treated and comparison

groups [39]. In general medical patients, Barsky et al. [11]

found that health care costs were almost doubled in the

patients who had high somatisation scores compared to the

remainder even after adjusting for the effect of other

psychiatric diagnoses.

Since we adjusted for depression, anxiety, and panic

disorder, the effect we have observed can be attributed to

somatisation, not to other psychiatric disorders. Only one

previous study has adjusted for other psychiatric disorders

and found that in functional gastrointestinal disorders in a

population-based sample, SCL-90 somatisation score was

the sole predictor of health-related quality of life in a

multivariate analysis [40]. Two clinic studies found similar

results [41,42], although one referred to extraintestinal

symptoms of IBS, which also refers to number of bodily

symptoms [3]. This strong association between somatisation

and health status raises the possibility that the negative

outcomes associated with IBS (impaired health status and

high costs) are attributable to the minority of IBS patients

who show somatisation.

One other study has shown reduction of health care costs

when somatisation disorder is successfully treated with

psychological treatment [23]. It was limited to patients who

would attend a psychiatric clinic for stress management,

which is unlikely to be representative of patients with

marked somatisation. The reduction of health care costs in

that study might have been due, in part, to the letter sent to

the patients' primary care physician recommending limited

investigations. Our trial did not include any such recommendation; thus, the reduced costs presumably relate to the

patients feeling better (Table 2).

Ours was a pragmatic trial, not an explanatory one;

hence, we do not have data to explain the mechanisms

underlying the improvements in health-related quality of

life and reduced costs in the quartile with a high

somatisation score. We did find a reduction of IBS

symptoms and abdominal pain, but the reduction of

depression was less marked, which is compatible with the

findings in systematic reviews that improvement in

symptoms appears to be independent of change in mood

[12,14,19]. A reduction of somatisation score has been

reported to occur with treatment of IBS by hypnotherapy,

where it was accompanied by reduction of anxiety rather

than depression [20].

There are a number of limitations of this study. It is

based on a secondary analysis of data collected in a trial,

which was not designed specifically for this purpose, and

numbers in the main analysis are small. This was a

pragmatic trial designed to assess cost-effectiveness of

psychotherapy and an SSRI antidepressant compared to

usual treatment and did not, therefore, include a placebo

group. We did not measure coping or other measures that

might have helped explain how our active treatments acted

independent of depression and pain. Our sample included

only patients with severe IBS; hence, our results may not

be generalisable to a wider group of patients with IBS. On

the other hand, we were able to recruit a very high

proportion of eligible patients; thus, our sample would be

representative of severe IBS, which has not responded to

usual treatment; less severe IBS probably includes fewer

patients with marked somatisation. Furthermore, the

numerous assessments in our study meant that we could

adjust for numerous confounders, especially other psychiatric disorders and abuse history.

The main clinical implication of this study is the

importance of enabling patients with IBS and a high

somatisation score to reach antidepressant or psychological

treatment. Left untreated, such patients do poorly their

quality of life deteriorates and they continue to incur high

health care costs. This study has reinforced the finding of the

main trial that such treatment for these patients is costeffective [24]. The outstanding research tasks are to identify

the exact mechanisms through which these treatments work

and try and identify a somatisation score that most closely

defines patients who have poor outcome if left untreated and

would benefit from treatment this is the theoretical basis

of a somatisation disorder [43,44].

Acknowledgments

The research team is thankful to the following: the MRC

for financing the study, the Health Authorities for financing

the psychotherapists, the patients who consented to take

part in the trial, and the doctors who prescribed the

antidepressant medication.

References

[1] Inadomi JM, Fennerty MB, Bjorkman D. Systematic review: the

economic impact of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther 2003;18:67182.

[2] Creed FH, Levy R, Bradley L, Drossman DA, Francisconi C, Naliboff

BD, Olden KW. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal

disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC,

Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, editors. Rome III. The

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean (Va): Degnon

Associates Inc., 2006. p. 295368.

Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the

comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what

are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002;122:

11401156.

Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Rigby C, Tomenson B,

Read N, Thompson DG. Reported sexual abuse predicts impaired

functioning but a good response to psychological treatments in patients

with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med 2005;67:

4909.

Leserman J, Li Z, Hu YJB, Drossman DA. How multiple

types of stressors impact on health. Psychosom Med 1998;60:

17581.

Creed F, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Palmer S, Rigby C, Tomenson B,

Guthrie E, Read N, Thompson DG. North of England IBS Research

Group; outcome in severe irritable bowel syndrome with and without

accompanying depressive, panic and neurasthenic disorders. Br J

Psychiatry 2005;186:50715.

North CS, Downs D, Clouse RE, Alrakawi A, Dokucu ME, Cox J,

Spitznagel EL, Alpers DH. The presentation of irritable bowel

syndrome in the context of somatization disorder. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2004;2:78795.

Miller AR, North CS, Clouse RE, Wetzel RD, Spitznagel EL, Alpers

DH. The association of irritable bowel syndrome and somatization

disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:2530.

Spiegel BM, Kanwal F, Naliboff B, Mayer E. The impact of

somatization on the use of gastrointestinal health-care resources in

patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:

226273.

Jackson J, Fiddler M, Kapur N, Wells A, Tomenson B, Creed

F. Number of bodily symptoms predicts outcome more

accurately than health anxiety in patients attending neurology,

cardiology, and gastroenterology clinics. J Psychosom Res

2006;60:35763.

Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Somatization increases medical

utilization and costs independent of psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:90310.

Lackner JM. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol

2004;72:110013.

Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic

syndromes. Lancet 2007;369:94655.

Jackson JL, O'Malley PG, Tomkins G, Balden E, Santoro J, Kroenke

K. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2000;108:6572.

Talley NJ. Antidepressants in IBS: are we deluding ourselves? Am J

Gastroenterol 2004;99:9213.

Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative

therapies in the irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med

2003;163:26574.

Quartero AO, Meineche-Schmidt V, Muris J, Rubin G, de Wit N.

Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the

treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2005:CD003460.

Creed F. How do SSRIs help patients with irritable bowel syndrome?

[comment] [Review] [30 refs]. Gut 2006;55:10657.

Kroenke K, Swindle R. Cognitivebehavioral therapy for somatization

and symptom syndromes: a critical review of controlled clinical trials.

Psychother Psychosom 2000;69:20515.

Palsson OS, Turner MJ, Johnson DA, Burnelt CK, Whitehead WE.

Hypnosis treatment for severe irritable bowel syndrome: investigation

of mechanism and effects on symptoms. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:

260514.

O'Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, Tomkins G, Balden E, Kroenke

K. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom

syndromes. J Fam Pract 1999;48:98090.

619

[22] Allen LA, Escobar JI, Lehrer PM, Gara MA, Woolfolk RL.

Psychosocial treatments for multiple unexplained physical symptoms: a review of the literature. Psychosom Med 2002;64:

939950.

[23] Allen LA, Woolfolk RL, Escobar JI, Gara MA, Hamer RM.

Cognitivebehavioral therapy for somatization disorder: a randomized

controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:15128.

[24] Creed F, Fernandes L, Guthrie E, Palmer S, Ratcliffe J, Read N,

Rigby C, Thompson D, Tomenson B, North of England IBS

Research Group. The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and

paroxetine for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology

2003;124:30317.

[25] Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Rigby C, Tomenson B,

Read N, Thompson DG, North of England IBS Research Group. Does

psychological treatment help only those patients with severe irritable

bowel syndrome who also have a concurrent psychiatric disorder? Aust

N Z J Psychiatry 2005;39:80715.

[26] Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new

measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom

Med 2002;64:25866.

[27] Thompson WG, Creed F, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Mazzacca G.

Functional bowel disorders and chronic functional abdominal pain.

Gastroenterol Int 1992;5:7591.

[28] Drossman DA, Li Z, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Creed FH, Thompson

DG, Read NW, Babbs C, Barreiro M, Bank L, Whitehead WE,

Schuster MM, Guthrie EA. Functional bowel disorders: a multicenter

comparison of health status, and development of illness severity index.

Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:98695.

[29] Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: administration, scoring, and procedures

manual II for the r(evised) version. 1st ed. Towson: Clinical

Psychometric Research, 1983.

[30] Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Olden KW, Leserman J, Barreiro MA.

Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness: review and

recommendations. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:78294.

[31] Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form Health Survey

(SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care

1992;30:47383.

[32] Hahn BA, Kirchdoerfer LJ, Fullerton S, Mayer E. Patient-perceived

severity of irritable bowel syndrome in relation to symptoms, health

resource utilization and quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

1997;11:5539.

[33] Whitehead WE, Burnett CK, Cook E, Taub E. Impact of irritable bowel

syndrome on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:224853.

[34] Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health

summary scales: a user's manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New

England Medical Centre, 1994.

[35] Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive

illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:27896.

[36] World Health Organisation, Division of Mental Health. Schedules for

clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Geneva, Switzerland: World

Health Organisation, 1994.

[37] Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, Tomenson B. A controlled trial of

psychological treatment for the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1991;100:4507.

[38] Akehurst RL, Brazier JE, Mathers N, O'Keefe C, Kaltenthaler E,

Morgan A, Platts M, Walters SJ. Health-related quality of life and cost

impact of irritable bowel syndrome in a UK primary care setting.

Pharmacoeconomics 2002;20:45562.

[39] Raine R, Haines A, Sensky T, Hutchings A, Larkin K, Black N, Raine

R, Haines A, Sensky T, Hutchings A, Larkin K, Black N. Systematic

review of mental health interventions for patients with common

somatic symptoms: can research evidence from secondary care be

extrapolated to primary care? BMJ 2002;325:1082.

[40] Halder SL, Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ.

Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality

of life: a population-based casecontrol study. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther 2004;19:23342.

620

F. Creed et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64 (2008) 613620

[41] Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, Lacy BE, Olden KW,

Crowell MD. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms

in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am

J Gastroenterol 2003;98:24549.

[42] Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, Chang L, Dulai GS, Mayer EA,

Naliboff B, Spiegel BMR, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, Chang L, Dulai GS,

Mayer EA, Naliboff B. Clinical determinants of health-related quality

of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med

2004;164:177380.

[43] Creed F, Barsky A. A systematic review of the epidemiology of

somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis. J Psychosom Res

2004;56:391408.

[44] Creed F, Creed F. Can DSM-V facilitate productive research into the

somatoform disorders? J Psychosom Res 2006;60:3314.

You might also like

- Gasteiger Klicpera Attitudes of ParentsDocument34 pagesGasteiger Klicpera Attitudes of ParentsAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Parents Attitude: Inclusive Education of Children With DisabilityDocument6 pagesParents Attitude: Inclusive Education of Children With DisabilityAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- CbclprofileDocument6 pagesCbclprofileAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Skin To Skin Final-AodaDocument2 pagesSkin To Skin Final-AodaAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Gargarita Gloria - David GruevDocument6 pagesGargarita Gloria - David GruevAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Parents Perceptions of Advocacy Activities and TH PDFDocument13 pagesParents Perceptions of Advocacy Activities and TH PDFAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- BakerBlacherCrnicEdelbrock2002 PDFDocument13 pagesBakerBlacherCrnicEdelbrock2002 PDFAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Alexitimia PredictorDocument8 pagesAlexitimia PredictorAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Prediction 3Document21 pagesPrediction 3Adina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Parental Stress in Families of Children With Disabilities: A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesParental Stress in Families of Children With Disabilities: A Literature ReviewAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Arousal/Anxiety Management Strategies: October 8, 2002Document23 pagesArousal/Anxiety Management Strategies: October 8, 2002Adina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Computer-Assisted, 2-D Virtual Reality System ForDocument7 pagesEvaluation of A Computer-Assisted, 2-D Virtual Reality System ForAdina Bîrsan-MarianNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Quarterly Progress Report FormatDocument7 pagesQuarterly Progress Report FormatDegnesh AssefaNo ratings yet

- 13 Alvarez II vs. Sun Life of CanadaDocument1 page13 Alvarez II vs. Sun Life of CanadaPaolo AlarillaNo ratings yet

- Reference Document GOIDocument2 pagesReference Document GOIPranav BadrakiaNo ratings yet

- Aircaft Avionics SystemDocument21 pagesAircaft Avionics SystemPavan KumarNo ratings yet

- Quinta RuedaDocument20 pagesQuinta RuedaArturo RengifoNo ratings yet

- Depression List of Pleasant ActivitiesDocument3 pagesDepression List of Pleasant ActivitiesShivani SinghNo ratings yet

- 2017 LT4 Wiring DiagramDocument10 pages2017 LT4 Wiring DiagramThomasNo ratings yet

- Drug Development: New Chemical Entity DevelopmentDocument6 pagesDrug Development: New Chemical Entity DevelopmentDeenNo ratings yet

- Injection MouldingDocument241 pagesInjection MouldingRAJESH TIWARINo ratings yet

- Mass SpectrometryDocument49 pagesMass SpectrometryUbaid ShabirNo ratings yet

- Data Performance 2Document148 pagesData Performance 2Ibnu Abdillah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Aliant Ommunications: VCL-2709, IEEE C37.94 To E1 ConverterDocument2 pagesAliant Ommunications: VCL-2709, IEEE C37.94 To E1 ConverterConstantin UdreaNo ratings yet

- ODocument11 pagesOMihaela CherejiNo ratings yet

- Hydrogen Production From The Air: Nature CommunicationsDocument9 pagesHydrogen Production From The Air: Nature CommunicationsdfdffNo ratings yet

- Calculation Condensation StudentDocument7 pagesCalculation Condensation StudentHans PeterNo ratings yet

- The Integration of Technology Into Pharmacy Education and PracticeDocument6 pagesThe Integration of Technology Into Pharmacy Education and PracticeAjit ThoratNo ratings yet

- Drill Site Audit ChecklistDocument5 pagesDrill Site Audit ChecklistKristian BohorqzNo ratings yet

- SM FBD 70Document72 pagesSM FBD 70LebahMadu100% (1)

- Analyzing Activity and Injury: Lessons Learned From The Acute:Chronic Workload RatioDocument12 pagesAnalyzing Activity and Injury: Lessons Learned From The Acute:Chronic Workload RatioLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Aseptic TechniquesDocument3 pagesAseptic TechniquesMacy MarianNo ratings yet

- FINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Document67 pagesFINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Jane ParkNo ratings yet

- SUPERHERO Suspension Training ManualDocument11 pagesSUPERHERO Suspension Training ManualCaleb Leadingham100% (5)

- TC 000104 - VSL MadhavaramDocument1 pageTC 000104 - VSL MadhavaramMK BALANo ratings yet

- Coles Recipe MagazineDocument68 pagesColes Recipe MagazinePhzishuang TanNo ratings yet

- Grain Silo Storage SizesDocument8 pagesGrain Silo Storage SizesTyler HallNo ratings yet

- AcquaculturaDocument145 pagesAcquaculturamidi64100% (1)

- Mental Status ExaminationDocument34 pagesMental Status Examinationkimbomd100% (2)

- ICSE Class 10 HRJUDSK/Question Paper 2020: (Two Hours)Document9 pagesICSE Class 10 HRJUDSK/Question Paper 2020: (Two Hours)Harshu KNo ratings yet

- Social Connectedness and Role of HopelessnessDocument8 pagesSocial Connectedness and Role of HopelessnessEmman CabiilanNo ratings yet

- Latihan Soal Bahasa Inggris 2Document34 pagesLatihan Soal Bahasa Inggris 2Anita KusumastutiNo ratings yet