Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 S8755722307000622 Main

Uploaded by

LKOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 S8755722307000622 Main

Uploaded by

LKCopyright:

Available Formats

RECOGNIZING AND AVOIDING

INTERCULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION IN

DISTANCE EDUCATION

A Study of the Experiences of Canadian Faculty and Aboriginal

Nursing Students

CYNTHIA K. RUSSELL, PHD, RN,* DAVID M. GREGORY, PHD, RN,y

W. DEAN CARE, EDD, RN,z AND DAVID HULTIN, MA

Language differences and diverse cultural norms influence the transmission and receipt of

information. The online environment provides yet another potential source of miscommunication. Although distance learning has the potential to reach students in cultural groups that

have been disenfranchised from traditional higher education settings in the past, intercultural

miscommunication is also much more likely to occur through it. There is limited research

examining intercultural miscommunication within distance education environments. This article

presents the results of a qualitative study that explored the communication experiences of

Canadian faculty and Aboriginal students while participating in an online baccalaureate nursing

degree program that used various delivery modalities. The microlevel data analysis revealed

participants beliefs and interactions that fostered intercultural miscommunication as well as

their recommendations for ensuring respectful and ethically supportive discourses in online

courses. The unique and collective influences of intercultural miscommunication on the

experiences of faculty and students within the courses are also identified. Instances of

ethnocentrism and othering are illustrated, noting the effects that occurred from holding

dualistic perspectives of us and them. Lastly, strategies for preventing intercultural miscommunication in online courses are described. (Index words: Distance learning; Aboriginal;

Baccalaureate education; Intercultural miscommunication; Social constructivism) J Prof Nurs

23:351 61, 2007. A 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

HE ABORIGINAL PEOPLE of Canada are attending

postsecondary institutions in increasing numbers

(Government of Canada, 1997). However, their level of

educational attainment still falls well below that of other

Canadians. The postsecondary enrollment rate among

the general population aged between 17 and 34 years is

4Professor, College of Nursing, The University of Tennessee Health

Science Center, Memphis, TN.

yProfessor, School of Health Sciences, University of Lethbridge,

Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.

zProfessor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg,

Manitoba, Canada.

Project Coordinator, Research and Evaluation Unit, Research and

Applied Learning, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, Winnipeg,

Manitoba, Canada.

Address correspondence to Dr. Russell: Acute and Chronic Care

Department, College of Nursing, The University of Tennessee Health

Science Center, Room No. 629, 877 Madison Ave., Memphis, TN

38163. E-mail: crussell@utmem.edu

8755-7223/$ - see front matter

approximately 10%, as compared with that among

Aboriginal people, who participate at a 6% level.

According to Voyageur (2001, p. 103), bthis causes grave

concern to First Nations leaders who wish their people to

be more integrated into the mainstream economy.

Education is seen as a means of achieving this goal.Q

According to a recent national task force report,

bAboriginal nursing students face formidable challenges

in completing post-secondary programsQ (Health Canada, 2002, p. 5). The seriousness of this situation is

exacerbated by an increasing need for Aboriginal nurses

in the workplace. Furthermore, it is well known that

Aboriginal people are underrepresented in science,

technology, and health-related programs and professions (MacIvor, 1995). There has been a recent

movement to increase the numbers of Aboriginal

students in the health professions. The overall goals

have been to increase the representation of Aboriginal

students in professional programs such as nursing and

Journal of Professional Nursing, Vol 23, No 6 (NovemberDecember), 2007: pp 351361

A 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

351

doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.01.021

352

RUSSELL ET AL

to improve their chances of succeeding. Given the

increasing use of distance education technologies in

nursing programs, it is imperative to understand

students perspectives of and experiences with technology-enhanced teaching and learning.

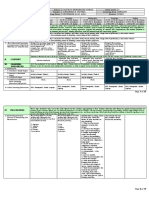

The University of Manitoba Faculty of Nursing

provides province-wide baccalaureate nursing education; it has program sites in Winnipeg and Norway House

(Figure 1). In partnership with the Red River College in

Winnipeg and the University College of the North, the

Faculty of Nursing offers joint baccalaureate nursing

programs in The Pas and Thompson. Aboriginal nursing

students account for 100% of the students enrolled in the

Norway House program and approximately 50% of those

enrolled in joint baccalaureate nursing programs in The

Pas and Thompson. The joint baccalaureate nursing

program at the Red River College also has a significant

number of Aboriginal nursing students, many of whom

Figure 1. Province of Manitoba with distance education sites.

INTERCULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION IN DISTANCE EDUCATION

eventually attend the main campus of the University of

Manitoba for their fourth year of study. The educational

programs use a variety of distance learning technologies

to deliver content to the remote sites.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to describe

Canadian Aboriginal undergraduate nursing students

experiences with distance education. Within their

interviews, students and faculty repeatedly identified

problematic communicative episodes that reflected a

phenomenon of intercultural miscommunication. The

study participants provided recommendations for

strategies that could prevent this miscommunication.

In this article, (a) the perspectives of faculty and

Aboriginal students about the discourse and situations

that occur within the online environment of a

baccalaureate program are described, (b) areas of

misunderstanding within courses are illustrated, and

(c) mechanisms that can be instituted within online

courses to prevent intercultural miscommunication

are identified.

Review of the Literature

The social constructivist approach to learning that was

introduced by Vygotsky (1978) focuses on the importance of culture and context in the formation of

knowledge. In this paradigm, learning is a dynamic

process mediated by language via social discourse. The

challenge of this theory is that neither culture nor

context provides a static environment for development.

Culture, cultural memberships, and cultural differences

are constructed and perpetuated by individuals while

they interact. Learning, like culture, must be dynamically negotiated in such an environment. In relation to

distance education, learning is an emerging attribute of

an individuals participation in an online community in

which social and individual processes work together to

facilitate the co-construction of knowledge.

Various authors have described the problematic nature

of cross-cultural learning situations, although not all of

their descriptions refer to online environments (Haulmark, 2002; Kataoka-Yahiro & Abriam-Yago, 1997;

Tylee, n.d.; Weitzel & Davidson-Shivers, 2004). In

Haulmarks study on eight Thai students experiences in

an online qualitative research methods course, issues for

students included adjusting to the technology, being

comfortable with delayed responses to questions, working with non-Thai students, and dealing with uncertainty.

Specifically in relation to nursing education, research

into the experiences of Asian students in cross-cultural

educational encounters revealed that they have difficulty with understanding informal speech, colloquialisms,

and metaphors (Weitzel & Davidson-Shivers, 2004).

These students are also asked to interact in ways that are

often different from their experiences, such as active

versus passive learning, group activities with strangers,

and open sharing of thoughts and beliefs. KataokaYahiro and Abriam-Yago (1997) described the tendency

of Asian students to perceive educators as authority

figures and to assume the role of passive learners.

353

Aboriginal students are a minority cultural group

within higher education institutions. Similar to other

minority groups, they are at risk of being unsuccessful in

their educational endeavors. Reeder, Macfadyen, Roche,

and Chase (2004) explored students experiences in a

computer-mediated course offered by the University of

British Columbia to culturally diverse groups across

Canada. Their research showed that, as compared with

other students, the Aboriginal learners in the course

posted significantly fewer messages and fewer long

messages, never directly addressed the faculty, and

demonstrated a drop-off in participation over time. In

the online classroom, Aboriginal students demonstrated

characteristics similar to those of the Asian students

described by Kataoka-Yahiro and Abriam-Yago (1997)

and Weitzel and Davidson-Shivers (2004).

Adding the element of distance education via the

internet has the potential to create further difficulties

because it introduces yet another cultural factor: the

unique cultural environment known as cyberculture.

Emerging from humancomputer interactions, the cyberculture has been described as constantly evolving and

rapidly mutating (Clarke, 1996; Polin, 2004), characterized by an official language of English, hyperspecialized

vocabulary, newbie snobbery, Anglo-American norms,

and qualities of aggressiveness, competitiveness, as well

as Western-style efficiency (Clarke, 1996; Reeder et al.,

2004). Far from being an antiseptic, neutral, and valuefree space in which persons of any cultural background

may find themselves part of the group, the internet often

highlights cultural differences between individuals as

well as between individuals and the dominant cyberculture of any space in which they participate (Reeder et al.,

2004; Tylee, n.d.). This can be obvious particularly

within online course environments.

Consideration of cultural issues is vital when designing

and using online environments (Seufert, 2000). Crow

(1993) offered a meta-orientation to the general university worldview and the Aboriginal worldview. He described the general university academic educational

viewpoint as representing the dominant Anglo-European

middle-class culture in its perspective as blinear, sequential, individualistic, competitive, dualistic, and with a

domination of natureQ (p. 199). In stark contrast to the

description of the university point of view, Crow

described the Aboriginal worldview as being bperceived

through a circular or spiral thought process or patterning,

which is holistic, pluralistic, and framed in an event

orientation that emphasizes cooperating groupsQ (p. 199).

Intercultural communication occurs when a message

is produced by a member of one cultural group for use by

a member of another cultural group (Lourens, 1999).

Given the competing cultural landscapes involved in

distance education (i.e., the individual, the society, and

the internet), there exists significant potential for

intercultural miscommunication. This can occur when

the message from one person to a person of another

cultural group is perceived in a negative manner.

Moreover, there can be complete failure in the transmis-

354

RUSSELL ET AL

sion of the intended message. McVay Lynch (2004) noted

that intercultural miscommunication is most often

bcaused by well-meaning statements, where each person

behaves according to his or her own cultural norms,

rather than by deliberate unpleasantnessQ (p. 172).

Chase, Macfadyen, Reeder, and Roche (2002) described key areas of cultural value differences that affect

successful online communication: First, the greater the

perception of cultural differences between online

participants is, the greater the number of incidents of

miscommunication becomes. Greater cultural differences lead to increased anxiety that serves to augment

the incidence of miscommunication. Second, cultural

attitudes toward person-to-person communication using the online environment vary greatly. Chase et al.

specifically noted variations in attitudes toward relationships, authority, and the group. Finally, the lack in

an online environment of elements that are present in

face-to-face communication, such as eye contact, gestures, and context perception, may serve to amplify

miscommunication.

The increasing use of distance education technologies in nursing education combined with educators

efforts to reach students in diverse cultural groups

mandates research into faculty and student communication experiences within online environments. The

results of such an exploration may help educators

proactively identify problematic situations, establish

mechanisms for monitoring courses for such situations,

and institute strategies to avoid or decrease the effect of

intercultural miscommunication.

Study Design and Methods

In the context of a larger study aimed at describing the

learning experiences of Aboriginal nursing students

studying with the use of distance modalities in a

baccalaureate program, we posed the question, bWhat

are Aboriginal nursing students and facultys perspectives of the discourse and situations that occur within

the online environment?Q This study used an interpretive description methodology (Thorne, Kirkham, &

MacDonald-Emes, 1997) that relied on an analytical

framework to orient the inquiry and provide direction

for analysis.

Focus group and individual interviews were used to

collect data from 61 successful students, 4 unsuccessful

students, and 12 faculty. The research underwent

ethical review at the University of Manitoba. After

providing a thorough description of the study to the

students, we welcomed and answered their questions;

the participants signed a consent form before the study

commenced. Interviews were conducted in locations

convenient for the students. Most of the focus groups

were conducted at the distance education sites, whereas

the individual interviews were completed offsite at

agreed-upon locations. Interviews were audiotaped

and transcribed verbatim. Each student was offered an

honorarium of $30 to cover costs associated with

participating in the research (e.g., child care and travel).

As a data collection method, focus groups were

deemed to be highly appropriate for obtaining the

perspectives of Aboriginal students given that focus

group interviews allow for group interaction in answering relevant questions (Krueger & Casey, 2000).

Aboriginal people are familiar with talking circles,

healing circles, and other forms of shared group

interactions. The focus groups fostered similar opportunities for collaborative sharing and storytelling. The

decision to conduct individual person-centered interviews with unsuccessful students was based on sensitivity to participants withdrawal from the course or

from the program. In addition, we believed that each of

the unsuccessful students had a unique story that

reflected a specific constellation of factors that, for

them, precluded their success in the program.

Questions asked during the interviews provided an

initial structure for collapsing the interview text into

broad and manageable categories. The categories were

subsequently further refined into more specific themes

using a content analysis approach. A microlevel analysis

of the transcripts was conducted to examine quotes

relevant to the participants discourses about other

people, areas of misunderstanding within courses, and

recommendations for preventing misunderstandings.

The trustworthiness of the findings was enhanced by

following several procedures. Each team member read

all the transcripts and participated in face-to-face and

audio/video conference team meetings throughout the

data collection process. A research associate, who had

lived in Northern Manitoba and was a graduate student

in the Native Studies Program of the University of

Manitoba, collected and transcribed all the data and was

a full participant in the research meetings and data

analysis process. Preliminary results were presented at a

conference, provoking additional thoughts about the

analysis. Team members contributed to the development and refinement of this article. Experts in baccalaureate nursing education and distance education

reviewed the article and raised questions that were

discussed by the team.

Setting and Sample

Each academic year, 400 to 500 students enroll in the

Faculty of Nursings undergraduate programs across all

sites (i.e., Winnipeg, Norway House, The Pas, and

Thompson). At the time of the study, the Norway House

baccalaureate nursing education program was the only

one in Canada offered to a First Nations community

(Indian Reserve). This site admitted approximately 20

new students every other year. The Norway House site

was operated in partnership with the University College

of the North and the Norway House Cree Nation. It was

supported by the Manitoba Keewatinook Ininew Okimowin, a political advocacy organization composed of

northern chiefs. The three distant sites were located in

communities controlled by different bands.

The distance technologies used at the university for

reaching Aboriginal students in distant sites included

INTERCULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION IN DISTANCE EDUCATION

LearnLinc, video conferencing, and WebCT. LearnLinc

provided synchronous two-way audio and text communication, whereas video conferencing offered synchronous two-way audio and video communication. WebCT

was a web-based asynchronous text and course management program.

Twenty-two focus groups were conducted with

current Aboriginal students from three sites within the

province of Manitoba, yielding 61 participants. Site

coordinators at each location assisted the projects

research associate with student recruitment. A purposive sampling strategy ensured the inclusion of Aboriginal students who had taken courses using one or more

of the distance technologies used at the university. Eight

focus groups with 15 participants were conducted in

Thompson, 10 focus groups with 24 participants were

conducted in The Pas, and 4 focus groups with 22

participants were conducted in Norway House. Study

participants included 17 prenursing (first-year and

second-year students), 33 third-year students, and 11

fourth-year students.

We thought it was important to learn from students

who had been unsuccessful in their learning at a

distance; therefore, we conducted individual interviews

with those students in each site (one from Thompson,

one from The Pas, and two from Norway House), for a

total of four interviews. These students had withdrawn

either from a distance course or from the program itself.

Finally, individual interviews were conducted with 12

faculty who had taught Aboriginal students in the

baccalaureate program using one or more of the

distance technologies.

Results

Beliefs and Interactions That Foster Intercultural

Miscommunication

The two primary themes of contrasting assumptions and

fractures and rifts in the discourse described the

participants beliefs and interactions that foster intercultural miscommunication. Each of these will be

described from the perspectives of students and

faculty.

Contrasting Assumptions

Contrasting assumptions were best described as statements that could, and often did, begin with btheyre like

this.Q These statements, made by faculty about students,

students about faculty, and students about other

students, reflected participants taken-for-granted attitudes about others. Students assumptions centered on

the benefits and drawbacks of on-campus life, negative

relationships with other sites, and perceptions of

faculty. Facultys assumptions dealt with the degree of

openness of Aboriginal students, the importance of

students cultural backgrounds, and students preparation for higher education and technology use.

Students Perspectives The distance learning program

Aboriginal students believed that students who attended

355

face-to-face classes at the main Winnipeg campus had

an advantage because every course in Winnipeg had a

face-to-face instructor whom each student would know.

I think the students in Winnipeg have an

advantage that we dont because the professor gets

to know the students, and its not fair to us who live

up here because. . .they have an advantage because

they are there. We dont. We just ask a question. . .[by introducing ourselves and asking the

question].

Many students, successful as well as unsuccessful,

perceived that they had no instructor when they used

the distance education modalities; their statements

included the following: bI was sort of expecting real

instructors,Q bI learn more and get more out of the

classes with an instructor,Q bIve heard that every course

in Winnipeg has an instructor,Q and bAs for the classes,

I guess its kind of different without an instructor. I feel

better when Im being taught by an instructor instead of

using technology.Q The students assumption that

distance education equated to having no instructor

led them to feel ignored and isolated by their faculty.

One student expressed the idea that, b[p]retty much

everything that weve learned, weve learned from each

other as a class.Q Some students believed that their

grades were lower than those of the on-campus

students because of their lack of personal interaction

with their faculty. Many students described having to

btake what we get to get doneQ in terms of not being

able to select instructors as they assumed on-campus

students could do.

Students comments also illustrated their assumptions

about the disadvantages of life bin the big cityQ and at

the university. For example, students described how

they would be fearful for themselves and their families if

they were required to go to the main campus. They

assumed that life in Winnipeg would be bintimidatingQ

and full of bdistractions.Q Part of the intimidation came

from the belief that Winnipeg was a big city with a fast

pace of life and a lack of security. The students were

concerned that if they took their families with them to

the campus, their children might get lost. Still other

students believed that a normal class size within the

main campus involved 200300 students among whom

they might have only ba couple of friends, but

everybody seems like a strange face.Q They feared there

would be no support within the main campus for their

personal and educational efforts and believed that

participation in small classes in their home communities

enabled them to know everyone well so that bif you

have trouble outside of class, youve got these other 15

20 students to help you.Q

Students expressed several negative assumptions

about other class sites. Many students noted a lack of

connection with their classmates from other sites,

voicing that they felt alone, frustrated, and discouraged.

They pointed to rivalries between sites and used these as

the basis for their beliefs that students from the other

sites were bvery opinionated,Q bcriticizing,Q and beach

356

town trying to outdo the other.Q Students had an

attitude that bwe are not always on the same wavelengthQ despite being from similar northern communities. In relation to the main campus, students assumed

that there were btwo different value sets. . .its totally

different between [northern] and southern people.Q

Comments prefaced by bI know its like that down

SouthQ reinforced the differences, rather than the

similarities, among students.

Finally, the students held several negative assumptions about their instructors. Some of these were class

related, including, bthey dont realize that we have other

classes,Q bthey dont like it when we log on from home

versus school,Q bits hard when your marks drop and it is

out of your control,Q and bthere are so many students

that the instructor doesnt know me.Q Some comments

reflected students views about facultys beliefs. Students

commented, bits like they dont give a rats ass about

people north of the perimeter,Q bwhen you have the

same instructor for several courses, they tend to label

you,Q and bI dont think she [the instructor] gives a

damn about us.Q

Facultys Perspectives. Faculty commented on their

beliefs about the communicative openness of Aboriginal

students. They assumed that Aboriginal students bare

very quiet and shy,Q bdont feel comfortable sharing,Q

blike to have a person to talk to instead of a microphone,Q bprefer working in small groups,Q bare audio

learners,Q bdont like to be asked questions,Q and bneed

more of a hands on.Q As a result of these assumptions,

faculty often used or avoided certain teaching strategies.

They were hesitant about calling students by name and

expecting them to talk in class. Because they believed

that students were familiar with storytelling, faculty

often included class activities that allowed for narrative

and personal experience sharing.

Faculty responses ranged from giving a great deal of

credence to students Aboriginal backgrounds to believing that all students should be treated the same

regardless of their heritage. An instructor who described

herself as reluctant to teach students according to their

cultural group felt that she would be bpigeon holing a

person and not respecting a person by saying dyou are an

Aboriginal, and here are all the issues you are going to

have.TQ However, most faculty identified a variety of

issues that they assumed to be relevant to Aboriginal

students and described how they attempted to incorporate these in their courses. Subjects specifically included

were bfamily issues,Q bculture shock,Q btransition issues,Q

boppression and colonialism,Q bmental health/illness,Q

and health care issues, such as suicide, alcoholism,

depression, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder.

Several faculty described their beliefs about Aboriginal students lack of preparation for higher education

and use of technology. Most faculty were convinced

that, as a group, Aboriginal students were less prepared

for their educational experiences as compared with their

main campus cohorts. Students lack of preparation was

RUSSELL ET AL

attributed to the level of elementary and secondary

education in Aboriginal communities. Some faculty

assumed that if they were in a face-to-face classroom

with students, rather than in distance education courses,

they would more quickly pick up on important body

language and realize who was struggling.

Fractures and Rifts in the Discourse. Fractures and rifts

in the discourse were specific interactions and situations

with critical, problematic, or striking sets of circumstances that resulted in negative attributions. These led

the participants to feel they were being treated badly or

differently from others. Whereas contrasting assumptions were based on participants beliefs about others,

fractures and rifts in the discourse reflected participants

negative attributions to specific occurrences. Students

examples focused on facultys insensitive comments

about the North and about Aboriginal students, feeling

accused by faculty and staff when technology failed, and

feeling reprimanded when faculty misperceived their

comments. Facultys stories were diverse and showed

their disbelief at some interactions as well as their

realization that students did not always perceive faculty

actions in the manner that faculty intended.

Students Perspectives. Students perceived that faculty

made insensitive comments about their local communities or about Aboriginal students. bThey [the faculty]

make stupid comments about [students in northern

communities], like asking ddo you guys get the paper?T

Were not that isolated!Q Another group of students

described how an instructor called them bkindergarten

kids.Q In more than one instance, students described

how they were referred to as byou people up NorthQ and

how they were not pleased to be referred to as a singular

group and in what they perceived as negative ways.

Students sensed an overemphasis on their Aboriginal

culture by the faculty, saying, bits almost a tune that

everybody who lives in the North is Aboriginal.Q Faculty

were perceived as not understanding the Aboriginal

culture and the settings in which students lived and

studied. In more than one instance, students reported

being told, bwell, just go to your bookstore,Q although

they had no local bookstore.

Several students perceived that faculty and staff

accused them when technology failed at the distant sites.

One students story was representative of that of others:

I tried logging onto WebCT and I was arbitrarily

locked out. My password had changed, unbeknownst to me. I had to track someone down in IT

[information technology], which here isnt always

the easiest thing to do. They implied it was somehow

something I had done wrong, whereas there was no

possible way. I had been logging on without

problems the whole year prior to today.

When technology failed, students often missed class

materials. They reported that faculty sometimes apologized, although students were told that they would need

to learn the materials on their own because bwere not

INTERCULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION IN DISTANCE EDUCATION

going to go back and lecture and penalize the other

students [who were not disconnected].Q Statements such

as this left the impression that the Aboriginal students

were less important than other students.

There were several situations in which the students

perceived that faculty were reprimanding them and

cutting off their communication. They described confrontational faculty who made students feel uncomfortable and bstupid at times because of his [the facultys]

choices of words.Q The asynchronous discussion board

was noted as a particular source of difficulty. In one

instance, a student used a particular word that had been

used in other courses, but bthe instructor reprimanded

her via e-mail saying that she could get in serious

trouble for cursing on the web site.Q The students

believed that this instructor was offended because she

was unsure what the students were talking about and

that bshe has no sense of humor.Q Students also noticed

the inconsistency of acceptable discussion board language across faculty.

Facultys Perspectives. Faculty described several disparate situations with Aboriginal students that perplexed

them or created tension between them and the students.

In one instance, a fourth-year student asked the

instructor in the middle of a class to recalculate her

class marks, which surprised the instructor because of

the requests inappropriateness in terms of timing. In

other instances, students walked in front of the video

camera with their backs to the camera and talked among

themselves during the video class. One instructor stated

her belief that the students behavior bwas not purposeful, but it is interfering.Q

When Aboriginal students missed tests because of

personal life crises, instructors questioned students

abilities to prioritize, even while saying, bprioritize may

be a judgmental word.Q Faculty noted the multiple

barriers that students faced in attending school,

including social problems, babysitting, difficult relationships, and English as a second language. Given the

tendency for the technology to sometimes fail, instructors often had to halt the flow of class and ask if each

site was still connected. One instructor found this

practice to be fodder for a skit in a student presentation, with the faculty being portrayed in the skit as

stopping every few minutes to say, bAre you there, The

Pas?Q Students at the distant sites sometimes fell asleep

during class, leading faculty to feel ba great sense of

miserable failure.Q Instances of technology failure

required classes to halt while the site that had been

disconnected dialed back into the class. This interruption was annoying to faculty as well as students from

other sites. Faculty wondered how the disconnections

could occur so frequently.

Recommendations for Avoiding Intercultural

Miscommunication

Students and faculty identified and agreed on several

strategies that could be implemented to avoid, decrease,

357

and/or eliminate intercultural miscommunication. Although the primary recommendation of both groups

was that faculty and students needed to take time to get

to know each other better, participants offered additional specifics.

Students Perspectives. Students thought it was important for faculty to get to know them as individuals and

as part of their local culture just as they believed in the

importance of learning about their faculty. Faculty

engaged in tangible activities that demonstrated to the

students their desire to understand them and their

culture. Faculty also exhibited attitudes that demonstrated to the students their desire to engage with the

students, learn from and with the students, and be

comfortable with the students.

Faculty actions that students perceived as positive

and requiring additional effort were described in each

of the focus groups. These efforts centered on e-mail

and telephone calls, attentiveness to each site, and

traveling to the distant sites from the main campus.

Students communicated more with faculty when they

were invited to bcall or e-mail after hours or at home.Q

When faculty invited such communication and provided a rapid response to students contacts, students

perceived that faculty understood them and their

needs for communication. Faculty who (a) purposefully took the time to ensure that students at each

distant site had their questions answered before the

end of a class and (b) expected each site to contribute

during class were described by students as bcaring

about usQ and bnot just seeing us as one big group in

the North.Q This personalization of the distance

education experience was important for the individualization of students educational experiences and the

collectivization of students cultural identity. Finally,

students recommended that each instructor teaching

by distance education should come to the distant sites

at least once, preferably at the beginning of the term.

Students saw this as an opportunity for faculty to

blearn about our way of learning, our culture, what

resources we have.Q Those faculty who had made the

effort to go to the distant sites at some point were

remembered by the students, who had little negative to

say about those faculty.

The importance of facultys interpersonal conduct

was a topic brought up at each focus group in one way

or another. Students appreciated faculty who brought

elements of humor and storytelling to the classroom.

Starting the day with a joke or comic strip was noted to

bmake the class lighter, makes me try harderQ; one

student responded, bI get respect for the teacher, dont

want to let them down, I put in the extra effort.Q

Students held a favorable view of faculty who told

stories about themselves, whether something from their

personal lives, their past education, or their nursing

experience. It was not merely the case that students

wanted to know about their faculty. When faculty used

their stories to make points in class, the students found

358

RUSSELL ET AL

it easier to anchor their learning on points with which

they were having difficulty grasping.

Facultys Perspectives. Faculty comments supported

students recommendations for the faculty to learn more

about the Aboriginal students perspectives and culture.

In addition, faculty focused on additional steps that

could be taken to maximize students learning and

minimize the potential for miscommunication.

Faculty described several tangible actions that they

undertook to better understand their Aboriginal students and to make use of students unique perspectives

and backgrounds. They agreed with students that going

in person to the distant sites was important, saying that,

bhow we start off with them, the introduction, is all

importantQ and bif you dont [travel to the other sites],

they dont find out who you are. Once they know [who

you are], you are approachable.Q Faculty who traveled

to the distant sites typically did not lecture during their

visit and instead had a social gathering that involved

food and relaxed conversations so they could get to

know their students.

Incorporating cultural components, either by relating

coursework to local sites or by asking Aboriginal students

to share their knowledge of the Aboriginal culture, was a

strategy used by several faculty. Some faculty commented

about the richness of their experiences in learning from

the students. They observed that as they bracketed their

preconceived notions of the Aboriginal culture, their

perspectives were enriched by viewing situations

through the eyes of the students. Similar to the students,

faculty commented on the importance of being expressive when teaching and using relevant stories as well as

humor in their classes. Faculty believed that these

strategies helped them reach the distant students and

showed faculty as personable and patient.

Faculty also described steps that they took to

maximize students learning at distant sites. A strategy

used by one faculty was to teach the distance and oncampus students at different times. Although this

meant doubly teaching the content, the faculty noted

that the distance learning program students bfelt cared

about and cared for because I could focus on their

specific needs.Q Students realized that the faculty was

doing this for them, and they noted their appreciation

in the interviews. Faculty acknowledged the limitations

of the technology and the tendency for the technology

to fail at times. They discussed the importance of bnot

stressing out if it goes downQ and the need to have

alternate plans if technology problems arose. Some

faculty spoke of the need for courses to help them

understand how to teach better using the available

distance education modalities, including components

that would help facilitate their communication with

distant and Aboriginal students.

Discussion

The discourses and experiences of the Aboriginal

students and faculty in an online baccalaureate nursing

program reflected numerous instances of intercultural

miscommunication. Whether anchored on assumptions

about others or arising from interpretations of dialogues and situations, participants readily offered

descriptions of miscommunication and how miscommunication affected the teachinglearning experiences

within the course. The findings of this study support

the social constructivism perspective of Vygotsky

(1978) because they highlight the importance of

culture and context as well as the negotiation of

meaning and learning. It was clear that the distance

education environment provided an additional cultural

context for participants to negotiate.

The results of this study also lend credence to the

findings of Haulmark (2002) on the potentially problematic nature of cross-cultural learning situations.

Haulmark established that the problems experienced

by Thai students in an online class with non-Thai

faculty and students related to the (a) social positions of

teachers and students, (b) relevance of the curriculum,

(c) cognitive abilities of students and faculty, and (d)

expected patterns of teacherstudent and student

student interactions. In this study, participants repeatedly referred to the importance of facultys and students

social positions and backgrounds as well as expected

interactional patterns, noting how these provided a

context for their course expectations.

Participants repeated references to btheyre like thisQ

when describing other individuals in this study have

implications for how faculty and students relate to

individuals whom they perceive as different from them.

Bunkers (2003) described the need to understand the

stranger, or the other, in our teachinglearning processes. She challenged educators to incorporate teaching

learning processes that foster understanding of the

stranger. In doing this, faculty can bprovide a safe place

for dialogue about diversity, the questioning of ones

own and others beliefs and assumptions, and provide

the opportunities for transformationQ (p. 309). Attentive

listening, authentic inquisitiveness, and true presence

are requisite behaviors in developing an understanding

of the other.

However, it is important to note that some assumptions held by faculty and students were correct. For

example, faculty spoke of the importance of telling

stories, the value of going to meet the remotely located

Aboriginal students in person, and the lack of nonverbal

cues in a distance environment that could increase their

awareness of students who might be struggling. Student

interviews supported the accuracy of these assumptions

held by faculty. What was interesting, however, is that

the assumptions were not described as being grounded

in the literature about Aboriginal learners. In contrast,

the assumptions were most often derived from other

colleagues experiences with teaching Aboriginal learners. This is problematic in that an ethnocentric bias of

faculty believing bwe know what works bestQ may not

always meet the needs of learners, especially learners of

a different cultural background.

INTERCULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION IN DISTANCE EDUCATION

The description of othering provided by MacCallum

(2002) holds relevance for understanding the perspectives of faculty and students in this study. Speaking about

us and them is an example of othering in which facultys

and students definitions are conceptualized in relation to

what each person is not (i.e., the other). Dualistic

perspectives of us and them serve to reify power

structures, lead to objectification of persons or groups,

and blind individuals to potentially harmful acts and

interventions, however well intentioned they may be.

The data in this research consistently showed that

when students and faculty connected with each other,

there were fewer negative attributions to facultys

comments, there was a better relationship between

faculty and students, and students were engaged more

deeply with the course material. In their study on

baccalaureate nursing students perspectives of effective

and ineffective classroom nursing instructors, Berg and

Lindseth (2004) found that personality, teaching method, presentation, demeanor/attitude, and enthusiasm

were the primary characteristics of effective instructors.

In another study on Nigerian nursing students stressors

and counseling needs, a positive association was found

between students psychologic distress and lecturers

who were inconsiderate and insensitive (Omigbodun,

Onibokun, Yusuf, Odukogbe, & Omigbodun, 2004). In

this study, Aboriginal students and faculty spoke about

each of these characteristics at some length.

It is clear that the Aboriginal students in this study

preferred learning that provided personal contact with

the instructor, defined as the person perceived as the

authority figure. The students also preferred learning

opportunities that related the course content to their or

their facultys personal experiences.

Implications

Consistent with the descriptions by McVay Lynch

(2004), the results of this study revealed that most

instances of intercultural miscommunication were

caused by well-meaning statements and behaviors rather

than deliberate unpleasantness. It is important for

faculty to recognize that cultural identity constitutes

an important part of each person in the class, including

them. McVay Lynch described how a code of conduct

established at the outset of a course provided a useful

strategy for helping the group avoid some incidents of

miscommunication that often occur among participants

of different cultures. This code of conduct can be

established in conjunction with students, encouraging

them to participate in the development of standards that

all course participants will respect and adhere to during

their courses. In this study, it was apparent that

participants desired a respectful and supportive online

community. McInnerney and Roberts (2004) supported

the provision of and adherence to guidelines for

successful online communication. In addition, they

stressed the importance of including more opportunities

for synchronous communication and deliberate attention to a warm-up period in the course.

359

Encouraging students and faculty to apply their MRI

(most respectful interpretation) to course dialogues and

situations is another strategy that can help defuse

potential instances of miscommunication. Lewis

(2000) offered a helpful mnemonic for communicating

online: WRITE, in which individuals should be Warm,

Responsive, Inquisitive, Tentative, and Empathetic.

Incorporating MRI and WRITE communication guidelines into course syllabi for didactic courses will serve as

constant reminders of the importance of a respectful

discourse within classes.

The findings of this study have implications for how

faculty conduct themselves and negotiate the boundaries

of oneself and others within face-to-face and online

courses. Qualitative researchers consistently encounter

situations in which oneself and others, or us and them,

must be negotiated to construct an understanding of those

persons who are unlike the researchers. The challenge of

bworking the hyphenQ identified by Fine (1994, p. 70) in

qualitative research has relevance for faculty who struggle

with the facultystudent hyphen and the artificial duality

of us and them. Translating Fines working-the-hyphen

concept for an academic teaching situation requires that

faculty create occasions for them and students to bdiscuss

what is, and is not, dhappening betweenTQ (p. 74).

The use of various distance education modalities in

the academic environment is increasing. It is important

to fully support faculty and students in learning more

not only about how to use the technology but also about

how to avoid instances of miscommunication that are

related to the use of technology. Several faculty

expressed their desire for courses to help them learn

more about teaching and learning via distance education. Material relevant to communicating online and the

uniqueness of this form of communication would be

useful for faculty. It is similarly important to provide

students with a strong orientation in distance education

and technology use. There is a tendency for confusion

when students traditional cultures collide with the

cultures of technology and distance education (Lourens,

1999). Making students and faculty aware of the

potential for miscommunication and offering mechanisms for incorporating traditional culture in the

distance education environment can facilitate the

teaching and learning experience.

Members of cultural groups have a strong ethnocentric tendencyan inclination to use their own culture to

evaluate the actions of individuals from other cultural

groups. Ethnocentrism was evident in the perspectives

of the students and faculty in this study. The tendency

of faculty to view Aboriginal students as a homogeneous

group belied the within-group heterogeneity of the

students. Students were from three distant sites, with

communities that varied widely and having experienced

very different situations in their upbringing. When fixed

conceptualizations of cultural characteristics were ascribed to a group, such as Aboriginal nursing students,

the uniqueness and differences of individuals within

that group were masked. Furthermore, teaching and

360

RUSSELL ET AL

learning strategies may tend to be applied in a blanket

manner, without accounting for individual learning

styles or preferences. Increasing the awareness of faculty

and students on the potential influence of ethnocentrism may provide them with a different insight on and

interpretation of the discourse and situations that occur

in online education.

Conclusions

Discourse ethics are motivated by values of respect,

truth, sincerity, fairness, equity, participation, and

accountability (McVay Lynch, 2004). Distance education, particularly with participants of different cultural

backgrounds, presents unique challenges to understanding and communicating. The cultures and values of

every participant in the online environment are an

inextricable part of each person. It is imperative that

nursing educators acknowledge the presence of diversity

within online groups, respect the uniqueness of each

student, and implement strategies to bridge the hyphen

between us and them. Our nursing programs must offer

opportunities for facultystudent reflections on the

teachinglearning process and systematically provide

faculty and students with guidance in negotiating their

differences within face-to-face and online courses if we

are to recruit, retain, and graduate students whose

backgrounds vary from those of their faculty.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Social Sciences and Humanities

Research Council of Canada for funding this research.

We also thank Drs. Susan Jacob and Victoria Murrell for

providing reviews and critiques on the manuscript.

References

Berg, C. L., & Lindseth, G. (2004). Students perspectives of

effective and ineffective nursing instructors. Journal of Nursing

Education, 43, 565 568.

Bunkers, S. S. (2003). Understanding the stranger. Nursing

Science Quarterly, 16, 305 309.

Chase, M., Macfadyen, L. P., Reeder, K., & Roche, J. (2002).

Intercultural challenges in networked learning: Hard technologies meet soft skills. First Monday, 7. Retrieved July 15, 2005,

from http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue7_8/chase/index.html.

Clarke, R. (1996). Cyberculture: Towards the analysis that

internet participants need. Accessed online on February 14,

2005 at http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger.Clarke/II/

CyberCulture.html.

Crow, K. (1993). Multiculturalism and pluralistic thought

in nursing education: Native American world view and the

nursing academic world view. Journal of Nursing Education, 32,

198 204.

Fine, M. (1994). Working the hyphens: Reinventing self

and other in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S.

Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 70 82).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Government of Canada. (1997). Basic departmental data,

1997. Ottawa: Ministry of Public Works and Government

Services.

Health Canada. (2002). Against the odds: Aboriginal nursing.

National Task Force on Recruitment and Retention Strategies.

Ottawa: Health Canada. Accessed online on February 14, 2005

at http://www.umanitoba.ca/nursing/research/aboriginal_

nursing.pdf.

Haulmark, M. (2002). Accommodating cultural differences

in a web-based distance education course: A case study.

Proceedings of the 9th Annual International Distance Education Conference, Texas A&M University, Austin, Texas,

January 2225, 2002.

Kataoka-Yahiro, M., & Abriam-Yago, K. (1997). Culturally

competent teaching strategies for Asian nursing students for

whom English is a second language. Journal of Cultural

Diversity, 4, 83 87.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A

practical guide for applied research (3rd ed).Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage Publications.

Lewis, C. (2000). Taming the lions and tigers and bears. In

K. W. White, & B. H. Weight (Eds.), The online teaching guide:

A handbook of attitudes, strategies, and techniques for the virtual

classroom (pp. 13 23). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Lourens, M. (1999). Breaking down social and cultural

barriers which impair the progress of students in higher and

distance education. Retrieved December 7, 2005, from http://

www.fernuni-hagen.de/ICDE/proceedings/parallel/lourens/

lourens.html.

MacCallum, E. J. (2002). Othering and psychiatric nursing.

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9, 87 94.

MacIvor, M. (1995). Redefining science education for

Aboriginal students. In M. Battiste, & J. Barman (Eds.), First

Nations education in Canada: The circle unfolds (pp. 73 98).

Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

McInnerney, J. M., & Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online learning: Social interaction and the creation of a sense of

community. Educational Technology & Society, 7, 73 81.

Retrieved October 13, 2005 from http://ifets.ieee.org/

periodical/7_3/8.pdf.

McVay Lynch, M. (2004). Learning online: A guide to success

in the virtual classroom. New York: Routledge Falmer.

Omigbodun, O. O., Onibokun, A. C., Yusuf, B. O., Odukogbe,

A. A., & Omigbodun, A. O. (2004). Stressors and counseling

needs of undergraduate nursing students in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Journal of Nursing Education, 43, 412415.

Polin, L. (2004). Learning in dialogue with a practicing

community. In T. M. Duffy, & J. R. Kirkley (Eds.), Learnercentered theory and practice in distance education: Cases from

higher education (pp. 17 48). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Reeder, K., Macfadyen, L. P., Roche, J., & Chase, M. (2004).

Negotiating cultures in cyberspace: Participation patterns and

problematics. Language Learning & Technology, 8, 88 105.

Retrieved March 3, 2005, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol8num2/

reeder/default.html.

Seufert, S. (2000). Trends and future developments:

Cultural perspectives of online education. In H. H. Adelsberger, B. Collis, & J. M. Pawlowski (Eds.), International

handbook on information technologies for education and

training. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Accessed online on

February 10, 2005 at http://llt.msu.edu/vol8num2/reeder/

default.html.

Thorne, S., Kirkham, S. R., & MacDonald-Emes, J. (1997).

Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing &

Health, 20, 169 177.

Tylee, J. (n.d.). Cultural issues and the online environment.

New South Wales, Australia: Charles Sturt University, Centre

INTERCULTURAL MISCOMMUNICATION IN DISTANCE EDUCATION

for Enhancing Learning and Teaching. Accessed online on

February 12, 2005 at http://www.csu.edu.au/division/celt/

resources/documents/cultural_issues.pdf.

Voyageur, C. J. (2001). Ready, willing, and able: Prospects

for distance learning in Canadas First Nations community.

Journal of Distance Education, 16, 102 112.

361

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of

higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Weitzel, M. L., & Davidson-Shivers, G. V. (2004). Effects

of metaphors for Asian and majority-culture students. Home

Health Care Management & Practice, 17, 14 21.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- How To Make A Million DollarsDocument32 pagesHow To Make A Million DollarsolufunsoakinsanyaNo ratings yet

- If You Give A Pig A Pancake Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesIf You Give A Pig A Pancake Lesson PlanLKNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Between Feminism and PsychoanalysisDocument280 pagesBetween Feminism and PsychoanalysisCorina Moise Poenaru100% (7)

- Historical Journal Entry Rubricworld HistoryDocument2 pagesHistorical Journal Entry Rubricworld Historyapi-241347803No ratings yet

- Analytical Philosophy in Comparative Perspective PDFDocument407 pagesAnalytical Philosophy in Comparative Perspective PDFCecco AngiolieriNo ratings yet

- Appraisal ReportDocument8 pagesAppraisal ReportLKNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - Lawn-B-Gone HistoryDocument15 pagesLecture 6 - Lawn-B-Gone HistoryLKNo ratings yet

- Grant PrepDocument2 pagesGrant PrepLKNo ratings yet

- Strategies To Support Ells in Mainstream Classrooms: MacmillanDocument4 pagesStrategies To Support Ells in Mainstream Classrooms: MacmillanLKNo ratings yet

- Abss Esl Lesson Plan: Model Performance Indicators (Mpis)Document2 pagesAbss Esl Lesson Plan: Model Performance Indicators (Mpis)LKNo ratings yet

- GR Comprehension Scaffolds by W. HareDocument29 pagesGR Comprehension Scaffolds by W. HareLK100% (2)

- Cactus Jam 3MADocument17 pagesCactus Jam 3MALK0% (1)

- Walk Two Moons 4MADocument16 pagesWalk Two Moons 4MALKNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in SexualityDocument27 pagesGender Differences in SexualityLKNo ratings yet

- RTI Progress Monitoring-Classroom: Appendix DDocument1 pageRTI Progress Monitoring-Classroom: Appendix DLKNo ratings yet

- Transition WordsDocument1 pageTransition WordsLKNo ratings yet

- Cultural Competence Checklist: Personal Reflection: Appendix ADocument1 pageCultural Competence Checklist: Personal Reflection: Appendix ALKNo ratings yet

- Drawing Conclusions/Making InferencesDocument9 pagesDrawing Conclusions/Making InferencesLKNo ratings yet

- 21 Ideas For ManagersDocument3 pages21 Ideas For Managersikonoclast13456No ratings yet

- Human ValuesDocument24 pagesHuman ValuesMinisha Gupta71% (7)

- Understanding The SelfDocument3 pagesUnderstanding The SelfMica Krizel Javero MercadoNo ratings yet

- The 7 Biggest Mistakes To Avoid When Learning ProgrammingDocument8 pagesThe 7 Biggest Mistakes To Avoid When Learning ProgrammingJumpsuit cover meNo ratings yet

- Lecture/workshop Downloads: Presentation Pisa ReferencesDocument3 pagesLecture/workshop Downloads: Presentation Pisa ReferencesTesta N. HardiyonoNo ratings yet

- 0 Forces and MotionDocument2 pages0 Forces and MotionHafizah NawawiNo ratings yet

- Math 10-4 Subtracting Fractions With Unlike DenominatorsDocument2 pagesMath 10-4 Subtracting Fractions With Unlike Denominatorsapi-284471153No ratings yet

- Evaluation Tool For Video Script: InstructionsDocument4 pagesEvaluation Tool For Video Script: InstructionsLimar Anasco EscasoNo ratings yet

- Edsc 304 Math Digital Unit PlanDocument3 pagesEdsc 304 Math Digital Unit Planapi-376809752No ratings yet

- Work Smarter Not Harder CourseraDocument5 pagesWork Smarter Not Harder Courserafujowihesed2100% (2)

- Psychoanalysis and Film MusicDocument94 pagesPsychoanalysis and Film MusicJohn WilliamsonNo ratings yet

- Raising Our Children, Raising OurselvesDocument2 pagesRaising Our Children, Raising OurselvesTrisha GalangNo ratings yet

- Job Rotation Is An Approach To Management Development Where An Individual IsDocument3 pagesJob Rotation Is An Approach To Management Development Where An Individual IsSajad Azeez100% (1)

- Rubrics For Prequel CreationDocument1 pageRubrics For Prequel CreationKristine Isabelle SegayoNo ratings yet

- Natural Language Processing State of The Art CurreDocument26 pagesNatural Language Processing State of The Art CurrePriyanshu MangalNo ratings yet

- DLL English q1 Week 6Document15 pagesDLL English q1 Week 6Alexandra HalasanNo ratings yet

- Business Jargon: Prepared by Diana Betsko, Liliia Shvorob and Veronica SymonovychDocument28 pagesBusiness Jargon: Prepared by Diana Betsko, Liliia Shvorob and Veronica SymonovychДіана БецькоNo ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Friday Thursday Wednesday Tuesday MondayDocument2 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Friday Thursday Wednesday Tuesday MondaychoyNo ratings yet

- Taks 2Document6 pagesTaks 2Juliana RicardoNo ratings yet

- Learning Compeencies Domain LC SS: Quarter 3Document4 pagesLearning Compeencies Domain LC SS: Quarter 3Yasmin G. BaoitNo ratings yet

- Sources of Information: Accessibility and Effectiveness: LessonDocument5 pagesSources of Information: Accessibility and Effectiveness: LessonJoseph Gacosta100% (1)

- Holm - An Introduction To Pidgins and CreolesDocument305 pagesHolm - An Introduction To Pidgins and CreolesDesta Janu Kuncoro100% (5)

- The End of Performance Appraisal: Armin TrostDocument189 pagesThe End of Performance Appraisal: Armin TrostVinay KumarNo ratings yet

- Human Emotion Detection Using Machine LearningDocument8 pagesHuman Emotion Detection Using Machine LearningIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- 5.a. Health Is Wealth LectureDocument62 pages5.a. Health Is Wealth LectureYüshîa Rivás GōmëźNo ratings yet

- The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street Act 2Document2 pagesThe Monsters Are Due On Maple Street Act 2api-594077974No ratings yet