Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tor To Rici 2014

Uploaded by

Anonymous 7OyXxSctqvOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tor To Rici 2014

Uploaded by

Anonymous 7OyXxSctqvCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

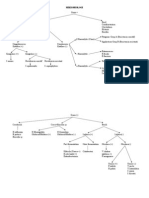

Traditional Endodontic Surgery Versus Modern

Technique: A 5-Year Controlled Clinical Trial

Silvia Tortorici, MD,* Paolo Difalco, DDS, PhD,* Luigi Caradonna, MD,* and Stefano Tete`, MD

Abstract: In this study, we compared outcomes of traditional

apicoectomy versus modern apicoectomy, by means of a controlled

clinical trial with a 5-year follow-up. The study investigated 938

teeth in 843 patients. On the basis of the procedure performed, the

teeth were grouped in 3 groups. Differences between the groups were

the method of osteotomy (type of instruments used), type of preparation of retrograde cavity (different apicoectomy angles and instruments used for root-end preparation), and root-end filling

material used (gray mineral trioxide aggregate or silver amalgam).

Outcome (tooth healing) was estimated after 1 and 5 years,

postoperatively. Clinical success rates after 1 year were 67% (306

teeth), 90% (186 teeth), and 94% (256 teeth) according to traditional

apicoectomy (group 1), modern microsurgical apicoectomy using

burns for osteotomy (group 2) or using piezo-osteotomy (group 3),

respectively. After 1 year, group comparison results were statistically

significant (P G 0.0001). Linear trend test was also statistically

significant (P G 0.0001), pointing out larger healing from group 1 to

group 3. After 5 years, teeth were classified into 2 groups on the basis

of root-end filling material used. Clinical success was 90.8% (197

teeth) in the silver amalgam group versus 96% (309 teeth) in the

mineral trioxide aggregate group (P G 0.00214). Multiple logistic

regression analysis found that surgical technique was independently

associated to tooth healing. In conclusion, modern apicoectomy

resulted in a probability of success more than 5 times higher (odds

ratio, 5.20 [95% confidence interval, 3.94Y6.92]; P G 0.001) compared with the traditional technique.

Key Words: Endodontic surgery, MTA, amalgam, prognosis,

statistics

(J Craniofac Surg 2014;25: 804Y807)

eriapical surgery, endodontic surgery, or apicoectomy is indicated when conservative endodontic treatment proves to be unsuccessful, nonsurgical endodontic retreatment is impractical, or

when a biopsy is to be obtained.1Y3 Apicoectomy involves resection

From the *Department of Stomatological Science, University of Palermo,

Palermo; and Department of Medical, Oral and Biotecnological Sciences, University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy.

Received April 30, 2013.

Accepted for publication August 26, 2013.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Paolo Difalco, DDS, PhD,

Department of Stomatological Science, University of Palermo, Palermo,

Via Pergusa,75, 92020, Palma di Montechiaro (Ag), Italy; E-mail:

paolodifalco@tin.it

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Copyright * 2014 by Mutaz B. Habal, MD

ISSN: 1049-2275

DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000398

804

of the root end (apex), followed by removal of the diseased periapical

tissues and then sealing of the pulp canal system to remove any

communication between the oral cavity and the periapical tissues.4

Periapical surgery is carried out using 2 surgical procedures: traditional and modern. The traditional endodontic surgical procedure

involved the use of burs and a slow-speed, straight handpiece with

sterile coolant for osteotomy and periapical amputation.3,5 Although

the hope is always to preserve as much tooth substance as possible, a

steep angle of resection (45 degrees to the long axis of the root on

average) is often necessitated to allow access for root-end cavity

preparation and filling with silver amalgam (SA).5 Regarding the

amount of apical resection, the literature consulted recommends an

apical resection of 3 mm in length with respect to the long axis of the

root.5 By contrast, modern endodontic surgery allows a more precise

procedure with no or minimal bevel of root-end resection, as well as a

biocompatible root-end filling material (such as ethoxybenzoate

cement or mineral trioxide aggregate [MTA]).5 It is a microsurgical

technique that uses magnification devices (loupes, surgical microscope, or endoscope), microinstruments for osteotomy, and root-end

preparation (microburs or tips). The goal of endodontic surgery is to

facilitate the regeneration of hard and soft tissues, including the

formation of a new attachment apparatus.6 Unfortunately, both traditional and modern surgical endodontic techniques have a different

model of healing. According to previously reported models for

healing after periapical surgery, we adopted the following classifications: complete healing, partial healing (incomplete healing),

uncertain healing, and no healing (or failure).7Y9 Several factors

influenced the type of healing, but surgical technique and root-end

filling material used are the most important. In the current study,

we performed endodontic surgery, using both traditional and modern

techniques. The study also compared 2 different materials used as

root-end filling: SA and MTA. In addition, we studied the outcomes

of 2 different methods for osteotomy used with modern technique:

osteotomy carried out with burs and a slow-speed, straight handpiece

and osteotomy performed with piezoelectric devices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We undertook a retrospective review of surgical records

(clinical charts, biologic tests, and radiologic investigations) held by

the Department of Stomatological Science of the University of

Palermo and identified all patients with periapical lesions of teeth

who had undergone periapical surgery and retrograde endodontic

treatment between 1985 and 2005.

A patient was considered eligible for the study if the records

had included a preoperative imaging of the lesion (intraoral

periapical radiographs, or computed tomography), the date of the

surgical treatment, a careful description of the periapical surgery

method, follow-up records with radiographic examination (intraoral

periapical radiographs), and a follow-up duration of 5 years.

Exclusion criteria were (1) unsatisfactory orthograde root

filling, determined radiographically (short or insufficient condensation); and (2) teeth with advanced periodontal disease (93-mm

pocket depth) or if the marginal bone level was entered as zero.

The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery

& Volume 25, Number 3, May 2014

Copyright 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery

& Volume 25, Number 3, May 2014

According to these criteria, we included in the study 843

patients who had undergone periapical surgery, comprising 670 teeth

with periapical lesions in the maxillary bone (347 in women and 323

in men) and 268 teeth with radicular lesions in the mandible (48 in

women and 220 in men). The following variables were extracted by

consulting the medical records: the age and sex of the patients and the

number and anatomic location of radicular lesions. The radiological

findings were noted. A single surgical team, including 2 endodontists

and 2 oral surgeons, all with more than 10 years of experience,

performed all the periapical surgery. The technical aspects of curettage and root-end sealing were similar for all the operators. Each

treatment was performed under local anesthesia (mepivacaine, 2%

with epinephrine), after disinfection of the mouth using 0.2%

chlorhexidine. All operators used a trapezoidal flap. We used traditional technique of apicoectomy and retrograde obturation with SA

(without zinc nonYgamma-2) until 1993; after this date, we

performed apicoectomy with modern techniques, using MTA

(ProRoot [gray]; Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Johnson City, TN) as rootend filling material. We grouped the patients on the basis of the

procedure performed. Differences between the groups were the

method of osteotomy, type of preparation of retrograde cavity, and

root-end filling material used. The first group included 393 patients

(205 male and 193 female patients), who were operated on with traditional techniques, performing osteotomy and apicoectomy with a

low-speed dental handpiece (Kavo Dentale Medizinische Instrumente

Vertriebsgesellschaft m.b.h., Biberach, Riss, Germany), root-end resection with a 45-degree bevel, and root-end preparation with traditional burs (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland).

Silver amalgam was the root-end filling material for this

group. The second group comprised 195 patients (116 male and 79

female patients) who were operated on with surgical endodontic

techniques, using a surgical microscope, osteotomy, and apicoectomy

with a low-speed dental handpiece, root-end resection with a 90degree bevel, root-end preparation with an ultrasonic source, and

retroangled, diamond-surfaced tips (EMS Silver Amalgam G.H.,

Nyon, Switzerland); then, the root canals were filled, using MTA. The

255 patients of the third group (142 male and 113 female patients)

were treated like the first group, but using piezoelectric devices for

both osteotomy and apicoectomy. After periapical surgery, each flap

was closed with a 4-0 silk suture, and hemostasis was obtained. The

patients were followed up after 15 days, 4 months, 6 months, 1 year,

and 5 years, with evaluation of certain criteria for success. According

to previously reported models for healing after periapical surgery, we

adopted the following classifications: complete healing, partial

healing (incomplete healing), uncertain healing, and no healing (or

failure). We classified apicoectomy as successful or complete healing

when patients showed a complete root canal filling and had bony

regeneration, as well as the absence of signs and symptoms such as

mobility, pain, and swelling. Intraoral periapical radiographs were

used to evaluate whether a root canal filling was satisfactory. Bony

regeneration was defined as the increase in radiopacity of the bone

around the apex of the root in the postoperative radiographs. By

contrast, apicoectomy was considered to be a failure when subjects

showed postoperative signs and symptoms, such as pain, gingival

swelling, mobility, hypersensitivity, tenderness on percussion, and

tenderness on palpation on the crown and/or in the apical area;

inability to masticate with the tooth; and the presence of fistula. The

radiological parameters of failure were an inadequate retrograde root

filling and no changes or increases of bony rarefaction around

the apex of the root. Consequentially, we classified healing as partial when patients had a complete root canal filling and absence

of symptoms, but their intraoral periapical radiographs showed

periapical radiotransparency smaller than that before the intervention.

By contrast, healing was considered to be uncertain when the tooth

had a complete root canal filling and absence of symptoms, and

Traditional vs Modern Endodontic Surgery

intraoral periapical radiographs showed periapical radiotransparency

smaller than that before the intervention, but there were cystic images

(radiotransparency surrounded by hard lamina) or root resorption.

When a multirooted tooth presented 1 healed root and 1 or 2 roots that

were not healed, we classified it as not healed.

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as mean T SD for continuous variables and

as absolute frequency and percentage for discrete or categorical

variables. Contingency table analyses were performed by the FisherFreeman-Halton statistics. The W2 for linear trend was also computed. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to study

relationships between the outcome variable (healing at 5 year) and

covariates. Fractional polynomial analysis was performed to study

the best fit between age and the outcome. A 2-sided value of P G 0.05

was intended as statistically significant. STATAversion 11.2 (StataCorp

LP, College Station, TX) for Windows was used for all the analyses.

RESULTS

The initial sample comprised 937 teeth in 843 patients (463

men and 385 women), and patients ages ranged from 20 to 56 years

(35.1 T 8.6 years). The majority of individuals was white (92%); the

rest were of African descent. Distribution of the teeth according to

location and surgical treatment group is presented in Table 1. The

most common outcome in all groups at the first control (15 days after

the intervention) was clinical uncertainty. Complete healing was not

observed until 6 months after intervention, except in 10 anterior teeth

(3 lower and 7 upper incisors), belonging to group 3, which showed

complete healing after only 4 months. We observed this improved

prognosis among the younger patients who were treated with minimal osteotomy. The clinical success (absence of clinical symptoms

or signs) rates after 1 year were 67% (306 teeth), 90% (186 teeth),

and 94% (256 teeth) in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively, whereas

complete healing was recorded in 60% (273 teeth), 71% (146 teeth),

and 73% (199 teeth). There were 27 teeth with unsatisfactory healing

(6%) in group 1, 6 (3%) in group 2, and 4 (1%) in group 3. Uncertain

healing was observed in 125 teeth (27%) in group 1, 14 teeth (7%) in

group 2, and 199 teeth (73%) in group 3 (Table 2). After 1 year,

group comparison indicated that there were statistically significant

differences (P G 0.0001). Linear trend test was statistically significant (P G 0.0001), pointing out larger healing from group 1 to group

3. At the follow-up after 5 years, the teeth were classified in 2 groups

(SA group and MTA group) only on the basis of the root-end filling

material used. Two hundred eight teeth were lost at follow-up

(dropout rate of 27.8%). After 5 years, the rates of teeth with clinical success were 90.8% (197 teeth) and 96% (309 teeth), in the SA

TABLE 1. Distribution of Teeth According to Location and Surgical

Treatment Groups

Tooth Type

Upper anterior teeth*

Upper premolars

Upper molars

Lower anterior teeth

Lower premolars

Lower molars

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

n = 510

n = 206

n = 273

188

75

72

19

36

120

74

36

28

10

23

35

128

41

27

8

37

32

Teeth treated with traditional apicoectomy (group 1), teeth treated with modern

apicoectomy using traditional burns for osteotomy and MTA as root-end filling material

(group 2), teeth treated with modern apicoectomy using piezo-osteotomy and MTA as

root-end filling material (group 3).

*Anterior teeth = incisors and canines.

* 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD

Copyright 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

805

The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery

Tortorici et al

TABLE 2. One-Year Distribution of Outcomes According to Tooth Location

and Surgical Treatment Groups

Group 1*

Upper anterior teeth

Upper premolars

Upper molars

Lower anterior teeth

Lower premolars

Lower molars

Total teeth healed

(% of healing)

Group 2

Upper anterior teeth

Upper premolars

Upper molars

Lower anterior teeth

Lower premolars

Lower molars

Total teeth healed

(% of healing)

Group 3

Upper anterior teeth

Upper premolars

Upper molars

Lower anterior teeth

Lower premolars

Lower molars

Total teeth healed

(% of healing)

Clinical Success

Clinical Failure

Complete

Partial

Uncertain

Unsatisfactory

112

45

43

12

21

40

273 (60%)

8

7

5

2

5

6

33 (7%)

53

21

20

5

8

18

125 (27%)

15

2

4

0

2

4

27 (6%)

54

26

20

5

16

25

146 (71%)

15

7

5

1

5

7

40 (19%)

5

3

2

1

2

1

14 (7%)

0

0

1

3

0

2

6 (3%)

93

31

18

5

28

24

199 (73%)

27

9

6

1

7

7

57 (21%)

5

1

2

2

1

2

13 (5%)

1

0

1

0

1

1

4 (1%)

Group comparison was statistically significant (P G 0.0001). Linear trend test was

statistically significant (P G 0.0001) as well, pointing out larger healing from group 1 to

group 3.

*Group 1: teeth treated with traditional apicoectomy.

Group 2: teeth treated with modern apicoectomy using traditional burns for

osteotomy and MTA as root-end filling material.

Group 3: teeth treated with modern apicoectomy using piezo-osteotomy and MTA

as root-end filling material.

group and MTA group, respectively. The corresponding rates of teeth

with relapse of lesions were 9.2% (20 teeth) and 4% (13 teeth)

(Table 3). Group comparison was statistically significant (P G

0.00214). Multiple logistic regression analysis found out that surgical technique was independently associated to tooth healing. In

fact, modern surgical technique resulted with a probability of success

more than 5 times higher (odds ratio, 5.2 [95% confidence interval,

3.5Y7.8]; P G 0.001) compared with traditional technique (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have reported success rates of apicoectomy

ranging from 43.5% to 92%.1,10,11 These differences may be the

result of variations in the surgical procedure performed, the magnification and lighting systems used, the root-end filling materials

applied, the evaluation period adopted, and/or the healing criteria

used to evaluate outcomes. There is a consensus that factors such as

age, sex, smoking, and tooth type do not significantly influence

postsurgical outcomes.12,13 The same authors reported that patients

with preoperative signs and symptoms have significantly lower

healing rates compared with patients without signs or symptoms.13,14

We have not considered the prognosis in the presence of

clinical signs or symptoms, because all our patients had symptoms

806

TABLE 3. Five Years Distribution of Outcomes According to Tooth Location

and Type of Material for Root-End Cavity Filling

Tooth Type per Group

Type of Healing

Tooth Type per

Group

& Volume 25, Number 3, May 2014

SA group

Upper anterior teeth

Upper premolars

Upper molars

Lower anterior teeth

Lower premolars

Lower molars

Total teeth healed (% of healing)

MTA group

Upper anterior teeth

Upper premolars

Upper molars

Lower anterior teeth

Lower premolars

Lower molars

Total teeth healed (% of healing)

Clinical Success

Relapse of Lesions

74

35

38

9

16

25

197 (90.8%)

9

3

2

1

2

3

20 (9.2%)

118

58

31

10

47

45

309 (96%)

6

1

4

0

0

2

13 (4%)

Group comparison was statistically significant (P G 0.00214).

and clinical or radiographic signs. The size of the marginal bone level

(the distance in millimeters of the surgical cavity from the alveolar

crest before closure of the mucosal flap) has been discussed in the

literature.12,13 We treated 203 teeth with a marginal bone level less

than 3 mm; in these cases, we applied a splint to immobilize the teeth

with poor stability. After 1 year, 115 (57%) teeth showed clinical

success, 80 (39%) were clinically unsuccessful, and 8 (4%) were not

followed up. More recently, endodontic surgery has seen various

innovations including the use of magnification devices and new

apical cements. These innovations have suggested that a conservative

microsurgical procedure and an adequate apical seal are important

factors that influence success rates in periapical surgery.2,11,13,15 A

systematic review performed by del Fabbro and Taschieri16 found no

significant difference in outcomes among patients treated using

magnifying loupes, surgical microscopes, or endoscopes. Magnification devices offer advantages such as minor surgical trauma for

both soft and hard tissues (minimal size of either the flap and

osteotomy), accuracy in the curettage of the periapical area, and a

detailed view of the root end with visualization of possible factors

that cause the persistence of pathosis, such as accessory canals that

are not detectable by the naked eye. We used no magnification

systems for the treatment of the first group, whereas we treated the

second and third groups with operative microscope. In both first and

second groups, we performed osteotomy with traditional burs,

whereas in the third group we used a piezoelectric surgical device for

osteotomy. Piezo-osteotomy is a minimally invasive technique that

allows bone to be cut while preserving soft tissues, including nerves

TABLE 4. Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis Results

Variable

Sex

Age*

Modern apicoectomy

Tooth type

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Intervals)

0.95

1,00

5,20

0.99

(0.62Y1,45)

(0.99Y1,01)

(3,94Y6,92)

(0.88Y1,12)

P

0.818

0.906

G0.001

0.921

Only the modern apicoectomy with MTA as root and filling material is independently associated to the outcome variable (tooth healing after 5 years) even when

corrected for sex, age, and tooth type.

*Age was transformed by fractional polynomial to find the best fit power (in our

case 3).

* 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD

Copyright 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery

& Volume 25, Number 3, May 2014

and the Schneiderian membrane.17,18 This technique revealed its

utility when we treated teeth that presented technical difficulties,

such as the close proximity of the apices to the mandibular canal or

the Schneiderian membrane. The success of apicoectomy depends

both on the technique for preparation of the root-end cavity and the

filling material used. There were no relevant differences in the

outcomes between the second and third group at 1 year. On the basis

of the current literature, we classified healing as complete, partial

healing (incomplete), uncertain, and no healing (or failure).7Y9

For the purposes of our study, complete healing and incomplete healing were considered as clinical success, whereas either

uncertain or no healing was considered as clinically unsuccessful.

We reported the evaluation of success and failure following endodontic surgery at 1 and 5 years, according to criteria suggested by

Rud et al. in 1972.9 Some studies have actually confirmed these

observations and reported that clinical and radiographic criteria

established for the prognosis possess a high degree of reliability after

a 1-year follow-up.9,19,20 Unfortunately, today only few studies

consider all these criteria to assess the prognosis. Our study showed

that at the 5-year follow-up the use of a modern microsurgical

endodontic technique and MTA as a root-end filling resulted in a

clinical success rate more than 5 times higher compared with the

traditional surgical technique.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the whole surgical team of the Department

of Stomatological Science of University of Palermo for collecting

and abstracting data.

REFERENCES

1. Vallecillo M, Munoz E, Reyes C, et al. Ciruga periapical de 29 dientes.

Comparacion entre tecnica convencional, microsierra y uso de ultrasonidos.

Med Oral 2002;7:46Y53

2. Saunders WP. A prospective clinical study of periradicular surgery using

mineral trioxide aggregate as a root-end filling. J Endod 2008;34:

660Y665

3. Tsesis I, Faivishevsky V, Kfir A, et al. Outcome of surgical endodontic

treatment performed by a modern technique: a meta-analysis of

literature. J Endod 2009;35:1505Y1511

4. Simhofer H, Stoian C, Zetner K. A long-term study of apicectomy

and endodontic treatment of apically infected cheek teeth in 12 horses.

Vet J 2008;178:411Y418

Traditional vs Modern Endodontic Surgery

5. Tsesis I, Rosen E, Schwartz-Arad D, et al. Retrospective evaluation

of surgical endodontic treatment: traditional versus modern technique.

J Endod 2006;32:412Y416

6. Karabucak B, Setzer FC. Conventional and surgical retreatment of

complex periradicular lesions with periodontal involvement. J Endod

2009;35:1310Y1315

7. Molven O, Halse A, Grung B. Observer strategy and the radiographic

classification of healing after endodontic surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac

Surg 1987;16:432Y439

8. Molven O, Halse A, Grung B. Incomplete healing (scar tissue) after

periapical surgery radiographic findings 8 to 12 years after treatment.

J Endod 1996;22:264Y268

9. Rud J, Andreasen JO, Jensen JE. Radiographic criteria for the assessment

of healing after endodontic surgery. Int J Oral Surg 1972;1:195Y214

10. Schwartz-Arad D, Yarom N, Lustig JP, et al. A retrospective radiographic

study of rootend surgery with amalgam and intermediate restorative

material. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod

2003;96:472Y477

11. Shearer J, McManners J. Comparison between the use of an ultrasonic tip

and a microhead handpiece in periradicular surgery: a prospective

randomised trial. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;47:386Y388

12. Wesson CM, Gale TM. Molar apicectomy with amalgam root-end

filling: results of a prospective study in two district general hospitals. Br

Dent J 2003;195:707Y714

13. von Arx T, Kurt B, Ilgenstein B, et al. Preliminary results and analysis of

a new set of sonic instruments for root-end cavity preparation. Int Endod

J 1998;31:32Y38

14. Lustmann J, Friedman S, Shaharabany V. Relation of pre- and

intraoperative factors to prognosis of posterior apical surgery. J Endod

1991;17:239Y241

15. Rahbaran S, Gilthorpe MS, Harrison SD, et al. Comparison of clinical

outcome of periapical surgery in endodontic and oral surgery units of a

teaching dental hospital: a retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;91:700Y709

16. del Fabbro M, Taschieri S. Endodontic therapy using magnification

devices: a systematic review. J Dent 2010;38:269Y275

17. Labanca M, Azzola F, Vinci R, et al. Piezoelectric surgery: twenty years

of use. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;46:265Y269

18. Schlee M. Ultraschallgestutzte ChirurgieYGrundlagen und

Moglichkeiten. Zahnarztl Impl 2005;21:48Y59

19. Rubinstein RA, Kim S. Long-term follow-up of cases considered healed

one year after apical microsurgery. J Endod 2002;28:378Y383

20. Jesslen P, Zetterqvist L, Heimdahl A. Long-term results of amalgam

versus glass ionomer cement as apical sealant after apicectomy. Oral

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995;79:101Y103

* 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD

Copyright 2014 Mutaz B. Habal, MD. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

807

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Genetic DiseasesDocument3 pagesGenetic DiseasesLhoshinyNo ratings yet

- Morning Report: AscitesDocument23 pagesMorning Report: AscitesBenny Yohanis GaeNo ratings yet

- HTP Visual1Document3 pagesHTP Visual1Queeniecel AlarconNo ratings yet

- The Bidirectional Relationship Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Metabolic DiseaseDocument14 pagesThe Bidirectional Relationship Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Metabolic DiseaseVenny SarumpaetNo ratings yet

- Tosoh Series 2147Document3 pagesTosoh Series 2147ShahinNo ratings yet

- Mci Ayn Muswil PtbmmkiDocument49 pagesMci Ayn Muswil PtbmmkiLucya WulandariNo ratings yet

- Quality Form Oplan Kalusugan Sa Deped Accomplishment Report FormDocument11 pagesQuality Form Oplan Kalusugan Sa Deped Accomplishment Report Formchris orlanNo ratings yet

- epidyolex-SmPC Product-Information - enDocument38 pagesepidyolex-SmPC Product-Information - enpharmashri5399No ratings yet

- Acid Base: by Adam HollingworthDocument8 pagesAcid Base: by Adam HollingworthIdrissa ContehNo ratings yet

- Main Conference ProgrammeDocument7 pagesMain Conference ProgrammeFaadhilah HussainNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument3 pagesNursing Care Plananon_984362No ratings yet

- Experiment #15: Screening Test For Low Titer Group "O" BloodDocument5 pagesExperiment #15: Screening Test For Low Titer Group "O" BloodKriziaNo ratings yet

- Comparison - of - ABAcard - p30 - and RSID - Semen - Test - Kits - For - Forensic - Semen - Identification PDFDocument5 pagesComparison - of - ABAcard - p30 - and RSID - Semen - Test - Kits - For - Forensic - Semen - Identification PDFEdward Arthur IskandarNo ratings yet

- Francisco GS Conference March 2022Document69 pagesFrancisco GS Conference March 2022SamuelNo ratings yet

- Beyond Wedge: Clinical Physiology and The Swan-Ganz CatheterDocument12 pagesBeyond Wedge: Clinical Physiology and The Swan-Ganz Catheterkromatin9462No ratings yet

- AW32150 - 30 - Surgical Guideline SYNCHRONY PIN - EN English - WebDocument64 pagesAW32150 - 30 - Surgical Guideline SYNCHRONY PIN - EN English - WebLong An DoNo ratings yet

- Helicobacter PyloriDocument251 pagesHelicobacter PyloriLuminita HutanuNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Probiotics and Antibiotic Growth PromoterDocument7 pagesThe Influence of Probiotics and Antibiotic Growth PromoterOliver TalipNo ratings yet

- Immobilization and Death of Bacteria by Flora Seal Microbial SealantDocument6 pagesImmobilization and Death of Bacteria by Flora Seal Microbial SealantinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Sex Education Prevents Teen PregnancyDocument2 pagesSex Education Prevents Teen PregnancyLeila Margrethe TrivilegioNo ratings yet

- Treating and Monitoring Hypomagnesaemia For Non-Critical Areas of TrustDocument3 pagesTreating and Monitoring Hypomagnesaemia For Non-Critical Areas of Trustramy.elantaryNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Typhoid FeverDocument5 pagesDiagnosis of Typhoid FeverpeterjongNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Painful EyeDocument9 pagesEvaluation of The Painful EyeMuthia Farah AshmaNo ratings yet

- Ansxiety NiceDocument465 pagesAnsxiety NiceAlex SanchezNo ratings yet

- Egurukul OrbitDocument8 pagesEgurukul OrbitbetsyNo ratings yet

- Oxygen Therapy For NurseDocument46 pagesOxygen Therapy For NurseselviiNo ratings yet

- Casilan, Ynalie Drug Study (Morphine)Document5 pagesCasilan, Ynalie Drug Study (Morphine)Ynalie CasilanNo ratings yet

- Mikrobiologi DiagramDocument2 pagesMikrobiologi Diagrampuguh89No ratings yet

- PolioDocument5 pagesPolioapi-306493512No ratings yet

- Effects of The Treatment Method of Reproductive Performance in Cows With Retention of Fetal MembranesDocument10 pagesEffects of The Treatment Method of Reproductive Performance in Cows With Retention of Fetal MembranesAlberto BrahmNo ratings yet