Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pedagogical Affect, Student Interest, and Learning Performance

Uploaded by

irinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pedagogical Affect, Student Interest, and Learning Performance

Uploaded by

irinCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 960 964

Pedagogical affect, student interest, and learning performance

Jos Lus Abrantes a,, Cludia Seabra b,1 , Lus Filipe Lages c,2

a

Instituto Politcnico de Viseu, Escola Superior de Tecnologia and Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Faculdade de Economia, Portugal

b

Instituto Politcnico de Viseu, Escola Superior de Tecnologia, Portugal

c

Faculdade de Economia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal and London Business School, UK

Received 1 March 2006; received in revised form 1 September 2006; accepted 1 October 2006

Abstract

Using a sample of more than 1000 students, this study reveals that students perceived learning depends directly on their interest, pedagogical

affect, and their learning performance and indirectly on the studentinstructor interaction, the instructor's responsiveness, course organization, the

instructor's likeability/concern, and the student's learning performance. Likeability/concern indirectly affects student interest by influencing

learning performance. The results yield recommendations for schools, department heads, and university administrators.

2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Pedagogy; Student behavior; Learning outcomes; Marketing education

1. Introduction

Educators play a major role in the formation of students

personal identities by stimulating their development into active

members of society (Willemse et al., 2005). Through the act of

education, teachers expect to transmit a broad body of

knowledge to learners. Teachers and students should work

together and dedicate themselves to the learning process and to

their school's objectives. Schools with a clear vision of teaching

and learning goals can make students and teachers more

productive (Silins and Mulford, 2004).

Issues relating to perceived learning (e.g., student evaluation

of instructors, course organization, student interest) receive

scant attention in the literature (e.g., Engelland et al., 2000;

Paswan and Young, 2002; Young et al., 2003). However,

because of innumerable measurement difficulties, the literature

includes no consensus regarding key influences of teaching

effectiveness and students learning (Marks, 2000). The lack of

Corresponding author. Tel.: +351 232 480590; fax: +351 232 424651.

E-mail addresses: jlabrantes@dgest.estv.ipv.pt (J.L. Abrantes),

cseabra@dgest.estv.ipv.pt (C. Seabra), lflages@fe.unl.pt (L.F. Lages).

URL: http://prof.fe.unl.pt/~lflages (L.F. Lages).

1

Tel.: +351 232 480598; fax: +351 232 424651.

2

Tel.: +351 21 3801 600; fax: +351 21 3886 073.

0148-2963/$ - see front matter 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.10.026

a solid theory in the field, together with a diversity of measures,

affects the reliability of existing findings because researchers

question whether existing findings are a consequence of

independent variables or of flawed operationalization. The

goal of this study is to develop an instrument that builds on

existing theory in the field to measure important, intangible

educational concepts for the enhanced identification of key

determinants of student perceived learning.

This article begins with an overview of the current literature

and then develops the conceptual framework and the hypotheses. A discussion of research methodology follows. Using data

from 1095 students, this study uses confirmatory factor analysis

and structural equation modeling to test the conceptual

framework empirically. The article concludes with implications

for theory and for managerial practice in schools.

2. Conceptual model

Building on previous research, the conceptual model

presents the major determinants of perceived learning. To

sum up the model briefly, studentinstructor interaction, the

instructor's responsiveness, course organization, and the

instructor's likeability/concern have varying affects on pedagogical affect, student interest, and learning performance, which

in turn affect students perceived learning (see Fig. 1). The

J.L. Abrantes et al. / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 960964

961

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework.

following discussion builds on these concepts and relationships

in greater detail.

Studentteacher interaction refers to the opportunity to ask

questions, express ideas, and have an open discussion in class.

Nonthreatening interactions allow students to ask questions,

practice the free expression of ideas, develop their own skills,

and improve class discussion (Paswan and Young, 2002).

Educators and pupils most frequently recognize nonthreatening

interactions as a teaching and learning method (Willemse et al.,

2005), and this method has a positive influence on student

ratings of instruction (Paswan and Young, 2002). A stronger

studentinstructor interaction also affects instructor involvement because an engaged instructor invests more in his or her

students. Students are attentive and know when instructors are

investing in them, and they will recognize these efforts (Paswan

and Young, 2002). Thus, studentinstructor interaction influences students perceptions of pedagogical affect.

H1. A higher degree of studentinstructor interaction leads to

a higher level of pedagogical affect.

The services literature informs the responsiveness concept

(Parasuraman et al., 1985). In education, responsiveness is the

willingness to help students by providing prompt service. A

strong relationship exists between instructor involvement and

student interest (Paswan and Young, 2002). Teachers must have

the capacity to know students needs and respond to them quickly.

Responsive teaching implies a capacity to engage in systematic

learning from the teaching context and practice and from a more

generalized theory of teaching (Hammond and Snyder, 2000).

Students are demanding consumers who want good and prompt

service, and they know when instructors are involved. When this

occurs, students respond in kind (Paswan and Young, 2002).

H2. A higher degree of instructor responsiveness leads to a

higher level of student interest.

Organization represents the course structure and refers to the

systematic relationship between concepts and course direction

(Marks, 2000). Educators organization, clarity, and comprehensiveness are important in the student learning process (Feldman,

1998). Course organization relates directly related to students

ability to handle uncertainty. An unstructured course can make

students feel uncomfortable and, consequently, has a negative

impact on their evaluations of both the instructor and themselves

(Marsh, 1987, 1991). Conversely, a more structured and

organized course may lead to a favorable instructor assessment

and self-evaluation (Marks, 2000; Marsh, 1991). Thus, organization positively affects learning and instructor evaluation.

H3. A higher degree of course organization leads to a higher

level of pedagogical affect.

Likeability/concern refers to the teacher's emotional qualities, namely, his or her caring disposition. Students evaluate

their instructors beyond their objective teaching and scientific

abilities. The duration and nature of relationships between

students and teachers influence the processes and outcomes of

teaching (Hammond and Snyder, 2000). Teachers should not

only be transmitters of knowledge and skills but should also

attend to their relationships with students. Students often want

to know if instructors are likeable rather than if they are

knowledgeable. In many situations, students are more interested

in finding out if the proposed lectures are entertaining than if the

content is accurate and up-to-date (Cahn, 1987). Teaching style

allied with personal attractiveness (i.e., likeability/concern)

enhances learning. Combining a degree of entertainment with

other aspects of quality teaching is likely to promote student

involvement and, consequently, student learning (Marks, 2000).

H4. A higher level of instructor likeability/concern leads to a

higher level of learning performance.

Learning performance assesses multiple dimensions of

learning outcomes, such as students self-evaluation of knowledge, understanding, and skills and their desire to learn more

(Young et al., 2003). Learning performance is commonly

associated with a more positive attitude toward the environment,

namely, courses and teachers (Duke, 2002; Dunn et al., 1990). If

students have positive attitudes toward learning achievements,

teachers are likely to be more willing to commit themselves to

their students (Paswan and Young, 2002), which in turn will lead

students to evaluate their teachers methods more positively.

H5. A higher degree of student learning performance leads to

a higher level of pedagogical affect.

Motivation variables also correlate with learning outcomes.

Students perceptions of course outcomes (e.g., an intellectually

962

J.L. Abrantes et al. / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 960964

challenging course) help them become more competent

(Paswan and Young, 2002) and more interested. When students

perceive their learning performance as relevant, they should

exhibit an increased interest in the course.

H6. A higher degree of student learning performance leads to

a higher level of student interest.

Learning performance relates with perceived learning

(Marks, 2000). Education level increases as students pass

through the following stages of learning: comprehension:

application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. These stages

help researchers evaluate the extent to which students attain

learning outcomes (Duke, 2002). Thus, overall course evaluation is a function of learning performance and instructor

evaluation (Gremler and McCollough, 2002). This leads to the

following hypothesis.

H7. Higher learning performance leads to higher perceived

learning.

Student interest reflects input into the course, such as

attention level in class, interest in learning the material,

perception of a course's intellectual challenge, and acquired

competence in the field. Student interest facilitates effective

teaching and creates a more favorable learning environment

(Marsh and Cooper, 1981). Students reject a learning

environment that runs contrary to their preferences (Hsu,

1999). When learners are more interested, they perceive

themselves as learning more (Tynjl, 1999), and this will

reflect their overall evaluation of the learning process.

H8. Higher student interest leads to higher perceived learning.

Teachers have a major influence in molding student values,

especially through their instructional approaches (Willemse et al.,

2005). Pedagogical affect refers to students positive thoughts

about or feelings toward the instructional methods used in class.

Students tend to prefer instructional methods that are more

experiential and interactive (Frontczak, 1998; Matthews, 1994),

encourage understanding, emphasize application, integrate theoretical and practical knowledge, and produce more transferable

knowledge (Frontczak, 1998; Karns, 1993; Tynjl, 1999).

Educators must understand the learning process to design and

implement teaching methods that align with students needs and

enhance learning (Hsu, 1999). When teachers use instructional

methods that are in line with students preferred learning styles,

learners develop more favorable attitudes toward their teachers

pedagogical attributes. This is a pedagogical affect (Richard et al.,

2000). A positive attitude toward teaching style leads to higher

achievement and learning performance (Dunn et al., 1990;

Paswan and Young, 2002; Young et al., 2003).

H9. A higher degree of pedagogical affect leads to higher

perceived learning.

3. Survey instrument and data collection

The study incorporated measures used in prior research to

develop an initial version of the instrument. People able to

understand the nature of the concept of these measures then

discussed these measures to produce revisions to the instrument.

After revisions, the discussion reports a pretest sample of 30

students to test the reliability of the factors through Cronbach's

alpha. The pretest results helped further refine the questionnaire.

Teachers from ten different Portuguese schools then delivered the

final questionnaires to the students (for a list of construct, items,

reliabilities, and their sources, see Appendix A) to complete in

class at the end of 2004. The study comprises 1095 questionnaires

from the ten schools. The largest school provided 173 completed

questionnaires, and the smallest completed 14. The average mean

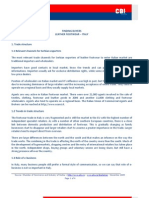

Fig. 2. Summary of significant relationships. aValues in upper rows are completely standardized estimates. Values in lower rows are t-values. p b 0.05, p b 0.01

(two-tailed tests).

J.L. Abrantes et al. / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 960964

of respondents by school was 110. Of the total number of

respondents, 47.5% were male, and 52.5% were female.

963

the analysis of their learning performance. Overall, students

value instructors while taking into account their personal

attractiveness and teaching qualities (Clayson and Haley, 1990).

4. Findings

5. Conclusion

A confirmatory factor analysis assessed the validity of the

measures, using full-information maximum likelihood estimation procedures in LISREL 8.54. Although the chi-square for

this model is significant (2 = 1104.16, df = 322, p b 00), the fit

indexes reveal a good model. The comparative fit index (CFI),

incremental fit index (IFI), TuckerLewis index (TLI), and root

mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of this

measurement model are 0.99, 0.99, 0.98, and 0.047, respectively. The large and significant standardized loadings of each

item on its intended construct provide evidence of convergent

validity (average loading size is 0.76). All possible pairs of

constructs passed Fornell and Larcker's (1981) discriminant

validity test (see Appendix A).

The final structural model has a chi-square of 1323.24

(df = 335, p b 0.00), and the fit indexes suggest a good fit of the

model to the data (CFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, and

RMSEA = 0.052). The estimation results for the structural

paths appear in Fig. 2. The results confirm all nine hypotheses.

The findings reveal that student interest is the primary

influence on perceived learning, followed by pedagogical affect

and learning performance. As prior research (Marks, 2000;

Young et al., 2003) has proposed, students learn more when

they are motivated and interested in the course. This also

confirms the expectation that students learn more in environments in which instructional methods are congruent with their

preferences (Young et al., 2003). Thus, instructional methods

that teachers use must be effective, useful, and satisfactory.

Teachers need to motivate their students to obtain better results.

Course organization has the greatest impact on pedagogical

affect, being twice as important as studentinstructor interaction and learning performance. An organized course contributes

to a more positive student evaluation of teachers and their

instructional methods. Because studentinstructor interaction is

also positively associated with pedagogical affect, this relationship appears to be important in the students evaluations of

teachers and their instructional methods. If students have a

strong and open relationship with their instructors, they will

invest more in the learning process and create a more positive

opinion about teachers and their methods. The relationship

between learning performance and pedagogical affect confirms

that students benefit from and enjoy learning processes that

have strong interactions (Paswan and Young, 2002).

Responsiveness is the major determinant of student interest,

being four times more important than learning performance.

This finding reveals the importance of the human factor and

confirms that though students might place importance on the

learned outcome, when they perceive teachers as investing in

and giving attention to them, they react positively and become

more interested (Paswan and Young, 2002).

Finally, a strong relationship exists between likeability/

concern and learning performance. Students evaluate themselves, their teachers, and their overall learning process through

The findings provide valuable information for teachers and

school managers, revealing that students appreciate interactive

and student-focused methods. Moreover, instructors personal

qualities and teaching characteristics (i.e., responsiveness,

likeability/concern, and instructional methods) strongly influence perceived learning.

The factors that this study reports try to capture the essence

of good teaching. First, teachers should use instructional

methods that get students involved. Second, instructors must

be agreeable and attentive because students evaluate them both

as people and as teachers. Third, instructors must be efficient in

delivering their service because such responsiveness increases

student interest. Finally, instructors should present courses that

are well structured and organized because course organization

has a significant, positive impact on perceived learning.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a research grant from NOVA

EGIDE to Lus Filipe Lages. The authors acknowledge the two

anonymous JBR reviewers for their feedback on a previous

version of the article.

Appendix A. Constructs, scale items, and reliabilities

Standardized t-values

coefficients

Studentinstructor interaction( = 0.82, vc(n) = 0.54, = 0.83)

(Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

V1 Instructor encouraged student to express opinion. 0.81

V2 Instructor is receptive to new ideas and others 0.81

views.

V3 Students had an opportunity to ask questions.

0.72

V4 Instructor generally stimulated class discussion. 0.59

Source: Paswan and Young (2002)

Responsiveness( = 0.78, vc(n) = 0.54, = 0.77)

(Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

V5 Tell students when they will be served.

V6 Serve students promptly.

V7 Always be eager to provide assistance.

Adapted from Engelland et al. (2000)

0.62

0.79

0.79

Organization ( = 0.84, vc(n) = 0.64, = 0.84)

(Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

V8 The course was well organized.

0.78

V9 The material was presented in an orderly manner. 0.78

V10 Instructor presents material in a clear and

0.83

organized manner.

Source: Marks (2000); adapted from Paswan and Young (2002)

30.57

30.87

26.08

20.20

21.56

29.42

29.64

29.63

29.48

32.10

Likeability/concern ( = 0.84, vc(n) = 0.63, = 0.84)

(Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

(continued on next page)

964

J.L. Abrantes et al. / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 960964

Appendix

(continued)A (continued )

Standardized t-values

coefficients

V11 I like the instructor as a person.

0.79

Likeability/concern ( = 0.84, vc(n) = 0.63, = 0.84)

V12 The instructor seems to have an equal concern 0.76

for all students.

V13 The instructor was actively helpful when

0.83

students had difficulty.

Source: Marks (2000)

Pedagogical affect( = 0.90, vc(n) = 0.70, = 0.90)

Overall, in this class the methods of instruction were

V14 1 ineffective 7 effective

V15 1 useless 7 useful

V16 1 unsatisfactory 7 satisfactory

V17 1 bad 7 good

Adapted from Young et al. (2003)

30.10

28.64

32.62

0.76

0.84

0.90

0.84

28.78

33.36

37.47

33.42

0.63

0.60

0.63

20.94

19.52

20.94

0.79

27.50

0.82

0.84

0.71

0.68

0.72

31.92

33.03

25.92

24.53

26.46

Perceived learning( = 0.79, vc(n) = 0.64, = 0.78)

(Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

V27 I am learning a lot in this class.

0.81

V28 As a result of taking this course, I have more 0.80

positive feelings toward this field of study.

Source: Marks (2000)

29.94

29.16

Student interest( = 0.76, vc(n) = 0.44, = 0.76)

(Scale 1 = strongly disagree/5 = strongly agree)

V18 You were interested in learning course material.

V19 You were generally attentive in class.

V20 You felt the course challenged you

intellectually.

V21 You have become more competent in this area.

Adapted from Paswan and Young (2002)

Learning performance( = 0.87, vc(n) = 0.58, = 0.87)

(Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree)

V22 The knowledge you gained.

V23 The skills you developed.

V24 Your ability to apply the material.

V25 Your desire to learn more about this subject.

V26 Your understanding of this subject.

Adapted from Young et al. (2003)

= internal reliability; vc(n) = variance extracted; = composite reliability.

References

Cahn S. Faculty members should be evaluated by their peers, not by their

students. Chron High Educ 1987;14:B2 [October].

Clayson DE, Haley DA. Student evaluations in marketing: what is actually

being measured? J Mark Educ 1990;12:917 [Fall].

Duke CR. Learning outcomes: comparing student perceptions of skill level and

importance. J Mark Educ 2002;24(3):20317.

Dunn R, Giannitti MC, Murray JB, Rossi I. Grouping students for instruction:

effects on learning style on achievement and attitudes. J Soc Psychol

1990;130(5):48594.

Engelland BT, Workman L, Singh M. Ensuring service quality for campus career

services centers: a modified SERVQUAL scale. J Mark Educ 2000;22(3):

23645.

Feldman KA. Effective college teaching from the students and faculty view:

matched or mismatched priorities? Res High Educ 1998;28:291344.

Fornell C, Larcker D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable

variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 1981;18(1):3950.

Frontczak NT. A paradigm for the selection, use and development of

experiential learning activities in marketing education. Mark Educ Rev

1998;8(3):2534.

Gremler DD, McCollough MA. Student satisfaction guarantees: an empirical

examination of attitudes, antecedents, and consequences. J Mark Educ

2002;24(2):15060.

Hammond LF, Snyder J. Authentic assessment of teaching in context. Teach

Teach Educ 2000;16:52345.

Hsu CHC. Learning styles of hospitality students: nature or nurture. Hosp

Manage 1999;18:1730.

Karns GL. Marketing student perceptions of learning activities: structure,

preferences, and effectiveness. J Mark Educ 1993;15(1):310.

Marks RB. Determinants of student evaluations of global measures of instructor

and course value. J Mark Educ 2000;22(2):10819.

Marsh H. Students evaluations of university teaching: dimensionality, reliability,

validity, potential biases, and utility. J Educ Psychol 1987;11(3):70794.

Marsh H. Multidimensional students evaluations of teaching effectiveness: a

test of alternative higher-order structures. Appl Psychol Meas 1991;83:

28596.

Marsh H, Cooper TL. Prior subject interest, students evaluations, and

instructional effectiveness. Multivariate Behav Res 1981;16:88104.

Matthews DB. An investigation of students learning styles in various disciplines

in colleges and universities. J Humanist Educ Dev 1994;33(3):6574.

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality

and its implications for future research. J Mark 1985;49:4150.

Paswan KA, Young JA. Student evaluation of instructor: a nomological

investigation using structural equation modeling. J Mark Educ 2002;24(3):

193202.

Richard D, Misra S, Auken SV. Relating pedagogical preferences of marketing

seniors and alumni to attitudes toward the major. J Mark Educ 2000;22(2):

14754.

Silins H, Mulford B. Schools as learning organizations Effects on teacher

leadership and student outcomes. Sch Eff Sch Improv 2004;15(34): 44366.

Tynjl P. Towards expert knowledge? A comparison between a constructivist

and a traditional learning environment in the university. Int J Educ Res

1999;31:357442.

Willemse M, Lunenberg M, Korthagen F. Values in education: a challenge for

teacher educators. Teach Teach Educ 2005;21:20517.

Young MR, Klemz BR, Murphy JW. Enhancing learning outcomes: the effects

of instructional technology, learning styles, instructional methods, and

student behavior. J Mark Educ 2003;25(2):13042.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- DCM Series Brushed Servo Motors: Electrical SpecificationsDocument3 pagesDCM Series Brushed Servo Motors: Electrical SpecificationsNguyen Van ThaiNo ratings yet

- 17-185 Salary-Guide Engineering AustraliaDocument4 pages17-185 Salary-Guide Engineering AustraliaAndi Priyo JatmikoNo ratings yet

- Committees of UWSLDocument10 pagesCommittees of UWSLVanshika ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Intrrogative: Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Mata Kuliah Bahasa Inggris DasarDocument9 pagesIntrrogative: Untuk Memenuhi Tugas Mata Kuliah Bahasa Inggris DasarRachvitaNo ratings yet

- All About Mahalaya PakshamDocument27 pagesAll About Mahalaya Pakshamaade100% (1)

- Quarter 4 English 3 DLL Week 1Document8 pagesQuarter 4 English 3 DLL Week 1Mary Rose P. RiveraNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Dam EngineeringDocument2 pagesAssignment On Dam EngineeringChanako DaneNo ratings yet

- Nucor at A CrossroadsDocument10 pagesNucor at A CrossroadsAlok C100% (2)

- JAG Energy Case StudyDocument52 pagesJAG Energy Case StudyRei JelNo ratings yet

- 1950's or The Golden Age of TechnologyDocument15 pages1950's or The Golden Age of TechnologyFausta ŽurauskaitėNo ratings yet

- Queueing in The Linux Network StackDocument5 pagesQueueing in The Linux Network StackusakNo ratings yet

- TPS6 LecturePowerPoint 11.1 DT 043018Document62 pagesTPS6 LecturePowerPoint 11.1 DT 043018Isabelle TorresNo ratings yet

- MSS Command ReferenceDocument7 pagesMSS Command Referencepaola tixeNo ratings yet

- METACOGNITION MODULEDocument4 pagesMETACOGNITION MODULEViolet SilverNo ratings yet

- A1 Paper4 TangDocument22 pagesA1 Paper4 Tangkelly2999123No ratings yet

- School Name Address Contact No. List of Formal Schools: WebsiteDocument8 pagesSchool Name Address Contact No. List of Formal Schools: WebsiteShravya NEMELAKANTINo ratings yet

- Finding Buyers Leather Footwear - Italy2Document5 pagesFinding Buyers Leather Footwear - Italy2Rohit KhareNo ratings yet

- Sally Su-Ac96e320a429130Document5 pagesSally Su-Ac96e320a429130marlys justiceNo ratings yet

- Digital Logic Technology: Engr. Muhammad Shan SaleemDocument9 pagesDigital Logic Technology: Engr. Muhammad Shan SaleemAroma AamirNo ratings yet

- Hrm-Group 1 - Naturals Ice Cream FinalDocument23 pagesHrm-Group 1 - Naturals Ice Cream FinalHarsh parasher (PGDM 17-19)No ratings yet

- Crema Coffee Garage - Understanding Caffeine Content of Popular Brewing Methods Within The Australian Coffee Consumer MarketDocument33 pagesCrema Coffee Garage - Understanding Caffeine Content of Popular Brewing Methods Within The Australian Coffee Consumer MarketTDLemonNhNo ratings yet

- Camaras PointGreyDocument11 pagesCamaras PointGreyGary KasparovNo ratings yet

- Sap Press Integrating EWM in SAP S4HANADocument25 pagesSap Press Integrating EWM in SAP S4HANASuvendu BishoyiNo ratings yet

- GTN Limited Risk Management PolicyDocument10 pagesGTN Limited Risk Management PolicyHeltonNo ratings yet

- Site Handover and Completion FormDocument3 pagesSite Handover and Completion FormBaye SeyoumNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 7development StrategiesDocument29 pagesCHAPTER 7development StrategiesOngHongTeckNo ratings yet

- Cleavage (Geology) : Structural Geology Petrology MetamorphismDocument4 pagesCleavage (Geology) : Structural Geology Petrology MetamorphismNehaNo ratings yet

- Research On Water Distribution NetworkDocument9 pagesResearch On Water Distribution NetworkVikas PathakNo ratings yet

- Bachelor's in Logistics and Supply Chain ManagementDocument2 pagesBachelor's in Logistics and Supply Chain ManagementKarunia 1414No ratings yet

- 2022 Australian Grand Prix - Race Director's Event NotesDocument5 pages2022 Australian Grand Prix - Race Director's Event NotesEduard De Ribot SanchezNo ratings yet