Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Dangers of Pesticides Associated With Public Health and Preventing of The Risks

Uploaded by

Mihai SebastianOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Dangers of Pesticides Associated With Public Health and Preventing of The Risks

Uploaded by

Mihai SebastianCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering

Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015, pp. 130-136

http://www.aiscience.org/journal/ijbbe

The Dangers of Pesticides Associated with Public

Health and Preventing of the Risks

Muhammad Sarwar*

Nuclear Institute for Agriculture & Biology (NIAB), Faisalabad, Punjab, Pakistan

Abstract

Pesticides in most cases are designed to kill pests; however, many pesticides can also pose risks to the peoples. But, in many

cases the amount of pesticide to which peoples are likely to be exposed, is too small to pose a health risk. To determine risks,

one must consider both the toxicity and hazard of the pesticide and the likelihood of exposure. A low level of exposure to a

very toxic pesticide may be no more dangerous than a high level of exposure to a relatively low toxicity pesticide. The health

effects of pesticides depend on the type of pesticide, some chemicals such as the organophosphates and carbamates; affect the

nervous system, while others may irritate the skin or eyes. Some pesticides may be carcinogens, but others can affect the

hormone or endocrine system in the body. The product label may have more specific instructions and try to identify and use

products that are low in toxicity. As a medical professional, collecting of a thorough and complete exposure history of patients

is essential to treat the case of pesticide poisoning. In either scenario, it is important to minimize the adults and children

exposure to pesticides. Precautionary, store all pesticides out of the reach of children and in case of any accidental occasion

contact to a medical professional. One way to minimize exposure to pesticides is to take approaches called Integrated Vector

Management (IVM) and Integrated Pest Management (IPM) that are vector and pest control strategies which use a combination

of methods to prevent and eliminate problems in the most effective and the least hazardous manner.

Keywords

Pesticides, Integrated Management, Public Health, Preventing Risks, Health Effects

Received: July 20, 2015 / Accepted: July 31, 2015 / Published online: August 9, 2015

@ 2015 The Authors. Published by American Institute of Science. This Open Access article is under the CC BY-NC license.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

1. Introduction

Pesticides are designed to kill or harm pests and because their

mode of action is not specific to one species, these often kill

organisms other than pests including humans. The World

Health Organization (2001) estimates that there are 3 million

cases of pesticide poisoning each year and up to 220,000

deaths, primarily in developing countries. The application of

pesticides is often not very precise, and unintended exposures

occur to other organisms in the general area where pesticides

are applied. Children, and indeed any young and developing

organisms, are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects

of pesticides. Even very low levels of exposure during

development may have adverse health effects.

* Corresponding author

E-mail address: drmsarwar64@yahoo.com

Pesticide exposure can cause a range of neurological health

effects such as memory loss, loss of coordination, reduced

speed of response to stimuli, reduced visual ability, altered or

uncontrollable mood and general behavior, and reduced

motor skills. These symptoms are often very subtle and may

not be recognized by the medical community as a clinical

effect. Other possible health effects include asthma, allergies

and hypersensitivity, and pesticide exposure is also linked

with cancer, hormone disruption, and problems with

reproduction and fetal development (Katarina, 2011).

Pesticide formulations contain both active and inert

ingredients. Active ingredients are that which kill the pest,

and inert ingredients help the active ingredients to work more

effectively. These inert ingredients may not be tested as

International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015, pp. 130-136

thoroughly as active ingredients and are seldom disclosed on

product labels. Solvents, which are inert ingredients in many

pesticide formulations, may be toxic if inhaled or absorbed

by the skin (Jeyaratnam, 1990; Levine, 2007).

2. Purpose of Pesticides in

Society

Pesticides are the only toxic substances released intentionally

into our environment to kill living things. This includes

substances that kill weeds (herbicides), insects (insecticides),

fungus (fungicides), rodents (rodenticides), and others.

Pesticides are used in our schools, parks and public lands.

Pesticides are sprayed on agricultural fields and wood lots.

Pesticides can be found in our air, our food, our soil, our

water and even in our breast milk. Because peoples use

pesticides to kill, prevent, repel or in some way adversely

affect some living pest organisms, the pesticides by their

nature are toxic to some degree. Even the least-toxic

products, and those that are natural or organic, can cause

health problems if someone is exposed to enough of these

(Khan et al., 2010; Sarwar et al., 2011). Due to the great

toxicity of insecticide, these are used heavily in the control of

pests or vectors that also impact applicator and public as

include subsequently:2.1. Organochlorines

Acute ingestion of organochlorine insecticides can cause a

loss of sensation around the mouth, hypersensitivity to light,

sound and touch, dizziness, tremors, nausea, vomiting,

nervousness, and confusion.

2.2. Organophosphates and Carbamates

Acute organophosphate and carbamate exposure causes signs

and symptoms of excess acetylcholine, such as increased

salivation and perspiration, narrowing of the pupils, nausea,

diarrhea, decrease in blood pressure, muscle weakness, and

fatigue. These symptoms usually decline within days after

exposure ends as acetylcholine levels return to normal. Some

organophosphates also have a delayed neurological reaction

characterized by muscle weakness in the legs and arms. The

human toxicity of organophosphates caused a decline in their

use and spurred the search for new alternatives.

2.3. Pyrethroids

Among the most promising alternatives to organophosphates

are synthetic pyrethroids. However, pyrethroids can cause

hyper-excitation, aggressiveness, uncoordination, wholebody tremors and seizures. Acute exposure in humans,

usually resulting from skin exposure due to poor handling

procedures, usually resolves within 24 hours. Pyrethroids can

131

cause an allergic skin response, and some pyrethroids may

cause cancer, reproductive or developmental effects, or

endocrine system effects.

The use of toxic pesticides to manage pest problems has

become a common practice around the world. Pesticides are

used almost everywhere, not only in agricultural fields, but

also in homes, parks, schools, buildings, forests and roads. It

is difficult to find somewhere where pesticides are not used

starting from the bug spray, under the kitchen sink, the

airplane to crop dusting acres of farmland, which filled our

world with pesticides. In addition, pesticides can be as well

found in the air we breathe, the food we eat and the water we

drink. And all the time there is more evidence surfacing that

human exposure to pesticides is linked to health problems.

For example, a study found that exposure to pesticide

residues on vegetables and fruits may double a childs risk of

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder- a condition that can

cause inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity in children

(Beseler et al., 2008).

3. Pesticides and Human

Health

The pesticides literature review, which is based on studies

conducted by a multi-university research teams, concludes

that the peoples should reduce their exposure to pesticides

because of links to serious illnesses. Results of this study

found consistent evidence of serious health risks such as

cancer, nervous system diseases and reproductive problems

in peoples exposed to pesticides through home and garden

exposure. Similar research has linked exposure to pesticides

to increased presence of neurological disorders, Parkinsons

disease, childhood leukemia, lymphoma, asthma and many

more (Lockwood, 2000; Sheiner et al., 2003).

Not only are pesticides dangerous to the environment, but

these are also hazardous to a person's health. Pesticides are

stored in colon, where these slowly but surely poison the

body. A person may not realize this, but when he is eating a

non-organic apple, is also eating several different pesticides

that have been sprayed on the apple. Even if a piece of fruit is

washed such as an apple, there are still many pesticides

lingering on it and these could have seeped into the fruit or

vegetable. Although one piece of fruit with pesticides cannot

kill, but if these build up in the body, they can be potentially

detrimental to health and should be avoided as much as

possible.

After countless studies, pesticides have been linked to cancer,

Alzheimer's disease and even birth defects. Pesticides also

have the potential to harm the nervous system, the

reproductive system, and the endocrine system. Pesticides

132

Muhammad Sarwar: The Dangers of Pesticides Associated with Public Health and Preventing of the Risks

can even be very harmful to fetuses because the chemicals

can pass from the mother during pregnancy or if a woman

nurses her child (Katarina, 2011).

Pesticides have been linked to a wide range of other human

health hazards, ranging from short-term impacts such as

headaches and nausea to chronic impacts like cancer,

reproductive harm, and endocrine disruption. Acute dangers,

such as nerve, skin and eye irritation and damage, headaches,

dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and systemic poisoning can

sometimes be dramatic, and even occasionally fatal. Chronic

health effects may occur years after even minimal exposure

to pesticides in the environment, or result from the pesticide

residues which are ingested through food and water. Study

conducted by researchers found a six fold increase in risk

factor for autism spectrum disorders for children of women

who are exposed to organochlorine pesticides (Alavanja et

al., 2004; Kamel and Hoppin, 2004; Montgomery et al.,

2008).

Pesticides can cause many types of cancer in humans; some

of the most prevalent forms include leukemia, non-Hodgkins

lymphoma, and brain, bone, breast, ovarian, prostate,

testicular and liver cancers. A study published found that

children who live in homes where their parents use pesticides

are twice as likely to develop brain cancer versus those that

live in residences in which no pesticides are used. Studies

found that farmers, who in most respects are healthier than

the population at large, have startling incidences of leukemia,

Hodgkins disease, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and many other

forms of cancer. There is also mounting evidence that

exposure to pesticides disrupts the endocrine system,

wreaking havoc with the complex regulation of hormones,

the reproductive system and embryonic development.

Endocrine disruption can produce infertility, a variety of birth

defects and developmental defects in offspring, including

hormonal imbalance and incomplete sexual development,

impaired brain development, behavioral disorders, and many

others. Examples of known endocrine disrupting chemicals

which are present in large quantities in our environment

include DDT, lindane, atrazine, carbaryl, parathion, and

many others. A multiple chemical sensitivity is a medical

condition characterized by the body's inability to tolerate

relatively low exposure to chemicals. This condition is also

referred to as environmental illness, which is triggered by

exposure to certain chemicals or environmental pollutants.

Exposure to pesticides is a common way and once the

condition is present, pesticides are often a potent trigger for

symptoms of the condition. The variety of these symptoms

can be dizzying, including everything from cardiovascular

problems to depression to muscle and joint pains (Gilden et

al., 2010; Sarwar, 2015 a; 2015 b; 2015 c; 2015 d; 2015 e).

4. Pesticides and Children

Children are particularly susceptible to the hazards associated

with pesticide uses; particularly they have not developed

their immune systems, nervous systems or detoxifying

mechanisms completely, leaving them less capable of

fighting the introduction of toxic pesticides into their

systems. Many of the activities that children engage in are

playing in the grass, putting objects into their mouth and

even playing on carpet; increase their exposure to toxic

pesticides. The combination of likely increased exposure to

pesticides and lack of bodily development to combat the

toxic effects of pesticides means that children are suffering

disproportionately from their impacts (Jurewicz and Hanke,

2008).

5. General Symptoms of

Pesticide Poisoning

Some health effects from pesticide exposure may occur in the

right away as anyone is exposed, some symptoms may occur

several hours after exposure and other effects may not be

noticed for years, for example cancer. Peoples come into

contact with pesticides in many ways, including when

pesticides are used in and around our homes and gardens,

used on pets or on the food eaten while working with

pesticides that is used in our communities or in our

environment. The risk of health problems depends not only

on how the ingredients are (Pesticide Ingredients), but also

on the amount of exposure to the product. In addition, certain

peoples like children, pregnant women and sick or aging

populations may be more sensitive to the effects of pesticides

than others (Pimentel et al., 2013).

5.1. Mild Poisoning

Any of the following symptoms of pesticide poisoning may

take place, irritation of the nose, throat and eyes or skin,

headache, dizziness, loss of appetite, thirst, nausea,

diarrhoea, sweating, weakness or fatigue, restlessness,

nervousness, changes in mood and insomnia.

5.2. Moderate Poisoning

Any of the mild symptoms, plus any of the following can

happen, like vomiting, excessive salivation, coughing, feeling

of constriction in throat and chest, abdominal cramps,

blurring of vision, rapid pulse, excessive perspiration,

profound weakness, trembling and muscular incoordination,

and mental confusion.

5.3. Severe Poisoning

In this category, any of the mild or moderate symptoms, plus

International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015, pp. 130-136

any of the following may occur, inability to breathe, extra

phlegm or mucous in the airways, small or pinpoint pupils,

chemical burns on the skin, increased rate of breathing, loss

of

reflexes,

uncontrollable

muscular

twitching,

unconsciousness and death.

Some symptoms of pesticide exposure may go away as soon

as the exposure stops and others may take some time to go

away. For peoples exposed to pesticides on a regular basis,

long-term health effects are a concern. Women who are

pregnant or breast-feeding should check with their doctors

before working with pesticides as some pesticides may be

harmful to the fetus (unborn baby) or to breast-fed infants.

6. Mode of Entry of Pesticides

in Body

Pesticides can enter the body during mixing, applying, or

clean-up operations. There are generally three ways a

chemical or material can enter into the body, through the skin

(dermal), through the lungs (inhalation) and by mouth

(ingestion).

6.1. Dermal Entry of Pesticides

In this mode of entry of pesticides in body, the absorption

occurs through skin. In most working situations, absorption

through the skin is the most common route of pesticide

exposure. Peoples can be exposed to a splash or mist when

mixing, loading or applying the pesticide. Skin contact can

also occur when a piece of equipment is touched, protective

clothing, or surface that has pesticide residue on it.

6.2. Inhalation of Pesticides

This mode of entry of pesticides in body is through the lungs

of a person. Inhalation may occur when working near

powders, airborne droplets (mists) or vapours. The hazard

from low-pressure applications is fairly low because most of

the droplets are too large to remain in the air. Applying a

pesticide with high pressure, ultra-low volume, or fogging

equipment can increase the hazard because the droplets are

smaller and these can be carried in the air for considerable

distances. Pesticides with a high inhalation hazard should be

labelled with directions to use a respirator.

6.3. Ingestion of Pesticides

The way of entry of pesticides into body by ingestion (by

mouth) may be less common way to be exposed and it can

result in the most severe poisonings. There are numerous

reports of peoples accidentally drinking a pesticide that has

been put into an unlabeled bottle or beverage cup or

container (including soft drink cans or bottles). Workers who

handle pesticides may also unintentionally ingest the

133

substance when eating or smoking if they have not washed

their hands first.

Because there are so many types of pesticides, accordingly,

their ity can vary greatly. In general, the risk of illness

increases as the concentration (strength) of the pesticide and

duration (length) of exposure increase. The likelihood of

becoming ill from exposure to pesticides depends on a

number of factors including, the type of pesticide (some

pesticides are more harmful than others), amount of pesticide

to which a person is exposed to (how much), concentration or

strength (how strong or dose), length of exposure (how long

time), route of entry into the body (skin, ingestion or

inhalation), and other carriers or chemicals in the pesticide

products.

7. Reducing the Risk of Health

from Use of Pesticide

It is necessary to always read the pesticide label first, and

then select the appropriate product for site to be treated,

method and goals. Thoroughly, read all precautions and

warnings on the pesticide label prior to use. The product

must be approved for the intended use and applied according

to label directions. These are intended to help for preventing

harmful exposures. Seek the least- pesticide option available

and take steps to minimize the exposure of pesticide

applicators, even when using low ity pesticides.

Choose to use an appropriate pesticide and keep in mind the

tips to minimize risk to infants and children. Allow plenty of

time for the pesticide to dry and the home to ventilate before

returning back. Keep children out of treated areas while

pesticides are being applied and until areas are dry. If a lawn

or carpeting has recently been treated with pesticides,

consider using shoes, blankets or another barrier between the

treated surface and children's skin. Be sure about the children

to wash their hands before eating, especially after playing

outdoors. If pesticide is applied to pets, be sure to keep

children from touching the pet until the product has

completely dried. Place ant, snail and rodent baits in locked

bait stations or safely out of reach of children. Never use

mothballs outside of sealed or airtight containers as children

often mistake mothballs for food when used improperly

around the home. Never use prohibited pesticides, such as

Chalk because it looks like normal chalk, and the pesticide

dust can be breathed in, get on kids hands or end up in their

mouths. Store all pesticides out of the reach of children and

in case of any accidental occasion contact to a medical

professional.

Be sure to store pesticides in their original containers and

never use food or beverage utensils or containers to mix or

134

Muhammad Sarwar: The Dangers of Pesticides Associated with Public Health and Preventing of the Risks

store pesticides. If someone in the household works with

pesticides, take steps to reduce the amount of pesticide

residues they bring into the home. If possible, wash and dry

the work clothes separate from family laundry. Finally, call to

a pesticides professional to learn more about the ity of

pesticides and ways to minimize exposure (Council on

Scientific Affairs, 1997).

Skilled pesticide applicators or peoples who work with

pesticides are encouraged to have regular medical check-ups.

In case of any accidental poisoning, tell to doctor about

which pesticides are working with or exposed to. Now this

article has informed about pesticides, it is up to applicators or

peoples to make the healthy choices that can lead them, and

to their friends and family to a healthier lifestyle. In order to

avoid as many pesticides as possible, it is better to grow

ones own fruits and vegetables in backyard. By doing this,

one can know that his food is not being sprayed with

chemicals and it tastes a lot fresher.

8. Future of Pesticides in

Public Health Programs

Public health pesticide use has been controversial since their

first use, and remains so to this day. As with all contentious

public policy issues, attitudes of neither side has achieved a

total victory, and probably neither ever will. One result of

this continuing struggle is the situation that should be added

to an ever-improving pesticide application technology, better

methods for surveillance of both vector-borne diseases and

vector infestations, and much better training of pesticide

applicators.

It is unlikely that effective control of public health pests can

ever be achieved based entirely on non-pesticide methods.

Pesticides remain useful and necessary tools, widely

available and frequently used by almost everyone. These

influence our daily lives in dozens of positive ways, they

increase our ability to produce food, help to protect us from

diseases like malaria and plague, and help to make our

general environment a more pleasant place in which to live.

However, pesticides are not without disadvantages, they are

expensive, may themselves create human health problems,

may damage pets and wildlife in some instances, may

actually increase our pest problems by suppressing beneficial

insects, and they may damage valuable agricultural crops.

Pesticide applicators should continually be aware of the

hazards associated with pesticide use, even though products

used today in public health programs are far less hazardous

than some years ago.

When any one considers pesticides as tools to be used in

vector control operations and not as the sole methods

available, efforts to promote development and use of

alternative tools become fully supportable. Some of these

alternatives include biological control, habitat modification,

genetic alteration of vector populations, and selective

application of vector control operations. An example of

selective application might be the ignoring of populations of

potential vector mosquitoes in areas where the chance of

contact of peoples with the vectors is very low. In this case, it

is more efficient for peoples to rely on protective clothing

and repellents to avoid mosquito bites (Sarwar, 2014 a; 2014

b; 2014 c; 2014 d).

Several vector control specialists have advocated the use of

the term Integrated Vector Management (IVM) to represent

the preferred modern approach to vector control, and to

mirror the modern approach to management of agricultural

pests called Integrated Pest Management (IPM). These are

called the important modern approaches for vector or pests

controls and there are only few differences in the principles

of IVM and IPM (Sarwar, 2013 a; 2013 b).

9. Pesticide Information for

Medical Professionals

As a medical professional, a Physician may have patients

with a known history of pesticide exposure, or patients who

report symptoms but are unsure about their pesticide

exposure. In either scenario, collecting a thorough and

complete exposure history of patients is essential. The

information required include, to what pesticide is the

patient exposed, when does the exposure occur, what is the

route of exposure (oral, dermal, inhalation), how long or

often is the patient exposed to the pesticide, when does the

patient's symptoms begin following the exposure, how long

have the symptoms persisted, have these improved or

worsened over the time and are there additional exposures

or circumstances that may be relevant. In some cases

laboratory testing for exposure to pesticides may be

considered. While laboratory testing is possible for many

pesticides, analytical methods are not available for all

pesticides active ingredients. Additionally, health-based

guidelines may not be established for pesticides detected in

biological samples. Detecting pesticides in the body does

not necessarily mean that a health effect can occur, or that

the current health complaints are related. For certain cases,

applicators may choose to consult with a clinical Biologist,

occupational or environmental health specialist for

assistance. There may be a medical Biologist staff available

at the hospital to physicians seeking consultation on

emergency cases of pesticide exposure (Sarwar et al., 2014;

2015).

International Journal of Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015, pp. 130-136

135

10. Conclusion

[8]

Katarina, L. 2011. Effects of Pesticides on Human Health.

Toxipedia Supported Sites, World Library of ology.

There are various methods that are implemented today in

various parts of the world to reduce the consequences of

pesticides caused to human beings. Pesticides are intended to

kill organisms that cause disease and threaten public health,

control insects, fungus and weeds that damage crops, control

pests that damage homes and structures which are vital to

public safety. Progressing to organic repellents is a logical

step to potentially help to reduce the chances of disease or

disease acceleration. Fruits and vegetables are just a few

types of food that should not be eaten if they are not organic

because the pesticide level is the highest on them. Children

are at greater risk from exposure to pesticides because of

their small size, relative to their size children eat, drink and

breathe more than adults. Their bodies and organs are

growing rapidly, which also make them more susceptible,

and in fact, children may be exposed to pesticides even while

in the womb. Before a pesticide is allowed to be used or sold,

it must undergo a rigorous scientific assessment process to

ensure that no harm can occur when pesticides are used

according to label directions. All pesticides registered in a

state, including for agricultural, forestry and domestic uses

must undergo this level of scrutiny. Always be sure to read

the products label first and reduce the risk of health problems

through the least- way to control the pest and learn about

integrated vector or pest management.

[9]

Khan, M.H., Sarwar, M., Farid, A. and Syed, F. 2010.

Compatibility of pyrethroid and different concentrations of

neem seed extract on parasitoid Trichogramma chilonis (Ishii)

(Hymenoptera:

Trichogrammatidae)

under

laboratory

conditions. The Nucleus, 47 (4): 327-331.

References

[1]

[2]

Alavanja, M.C., Hoppin, J.A. and Kamel, F. 2004. Health

effects of chronic pesticide exposure: cancer and neuroity.

Annu. Rev. Public Health, 25: 155-197.

Beseler, C.L., Stallones, L., Hoppin, J.A., Alavanja, M.C.,

Blair, A., Keefe, T. and Kamel, F. 2008. Depression and

pesticide exposures among private pesticide applicators

enrolled in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ. Health

Perspect. 116 (12): 1713-1719.

[3]

Council on Scientific Affairs. 1997. Educational and

informational strategies to reduce pesticide risks. Prev. Med.,

26 (2): 191-200.

[4]

Gilden, R.C., Huffling, K. and Sattler, B. 2010. Pesticides and

health risks. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs., 39 (1): 103110.

[10] Levine, M.J. 2007. Pesticides: A Time Bomb in our Midst.

Praeger Publishers. p. 213-214.

[11] Lockwood; A.H. 2000. Pesticides and parkinsonism: Is there

an etiological link? Curr. Opin. Neurol., 13 (6): 687-690.

[12] Montgomery, M.P., Kamel, F., Saldana, T.M., Alavanja, M.C.

and Sandler, D.P. 2008. Incident diabetes and pesticide exposure

among licensed pesticide applicators: Agricultural Health Study,

1993-200. Am. J. Epidemiol., 167 (10): 235-246.

[13] Pimentel, D., Culliney, T.W. and Bashore, T. 2013. Public

health risks associated with pesticides and natural toxins in

foods. IPM World Textbook. Regents of the University of

Minnesota.

[14] Sarwar, M. 2013 a. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) - A

Constructive Utensil to Manage Plant Fatalities. Journal of

Agriculture and Allied Sciences, 2 (3): 1-4.

[15] Sarwar, M. 2013 b. Development and Boosting of Integrated

Insect Pests Management in Stored Grains. Journal of

Agriculture and Allied Sciences, 2 (4): 16-20.

[16] Sarwar, M. 2014 a. Dengue Fever as a Continuing Threat in

Tropical and Subtropical Regions around the World and

Strategy for Its Control and Prevention. Journal of

Pharmacology and ological Studies, 2 (2): 1-6.

[17] Sarwar, M. 2014 b. Proposing Solutions for the Control of

Dengue Fever Virus Carrying Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae)

Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse).

Journal of Pharmacology and ological Studies, 2 (1): 1-6.

[18] Sarwar, M. 2014 c. Proposals for the Control of Principal

Dengue Fever Virus Transmitter Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus)

Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Ecology and

Environmental Sciences, 2 (2): 24-28.

[19] Sarwar, M. 2014 d. Defeating Malaria with Preventative

Treatment of Disease and Deterrent Measures against

Anopheline Vectors (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of

Pharmacology and ological Studies, 2 (4): 1-6.

[20] Sarwar, M. 2015 a. Controlling Dengue Spreading Aedes

Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) Using Ecological Services by

Frogs, Toads and Tadpoles (Anura) as Predators. American

Journal of Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 1 (1): 18-24.

[5]

Jeyaratnam, J. 1990. Acute pesticide poisoning: A major

global health problem. World Health Stat. Q., 43 (3): 139-144.

[21] Sarwar, M. 2015 b. Elimination of Dengue by Control of

Aedes Vector Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) Utilizing

Copepods (Copepoda: Cyclopidae). International Journal of

Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, 1 (1): 53-58.

[6]

Jurewicz, J. and Hanke, W. 2008. Prenatal and childhood

exposure to pesticides and neurobehavioral development:

Review of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Occup. Med.

Environ. Health, 21 (2): 121-132.

[22] Sarwar, M. 2015 c. Reducing Dengue Fever through

Biological Control of Disease Carrier Aedes Mosquitoes

(Diptera: Culicidae). International Journal of Preventive

Medicine Research, 1 (3): 161-166.

[7]

Kamel, F. and Hoppin, J.A. 2004. Association of pesticide

exposure with neurologic dysfunction and disease. Environ.

Health Perspect., 112 (9): 950-958.

[23] Sarwar, M. 2015 d. Control of Dengue Carrier Aedes

Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) Larvae by Larvivorous Fishes

and Putting It into Practice Within Water Bodies. International

Journal of Preventive Medicine Research, 1 (4): 232-237.

136

Muhammad Sarwar: The Dangers of Pesticides Associated with Public Health and Preventing of the Risks

[24] Sarwar, M. 2015 e. Role of Secondary Dengue Vector

Mosquito Aedes albopictus Skuse (Diptera: Culicidae) for

Dengue Virus Transmission and Its Coping. International

Journal of Animal Biology, 1 (5): 219-224.

[25] Sarwar, M., Ahmad, N., Bux, M., Nasrullah and Tofique, M.

2011. Comparative field evaluation of some newer versus

conventional insecticides for the control of aphids

(Homoptera: Aphididae) on oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.).

The Nucleus, 48 (2): 163-167.

[26] Sarwar, M.F., Sarwar, M.H. and Sarwar, M. 2015.

Understanding Some of the Best Practices for Discipline of

Health Education to the Public on the Sphere. International

Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences, 2

(1): 1-4.

[27] Sarwar, M.H., Sarwar, M.F. and Sarwar, M. 2014.

Understanding the Significance of Medical Education for

Health Care of Community around the Globe. International

Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences, 1

(2): 149-152.

[28] Sheiner, E.K., Sheiner, E., Hammel, R.D., Potashnik, G. and

Carel, R. 2003. Effect of occupational exposures on male

fertility: literature review. Ind. Health, 41 (2): 55-62.

[29] World Health Organization. 2001. International code of

conduct on the distribution and use of pesticides by Food and

Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2001.

You might also like

- Advantages and Disadvantages of AgrochemicalsDocument3 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Agrochemicalsmldc200667% (3)

- Pesticides and Human Health ConclusionDocument8 pagesPesticides and Human Health Conclusionsameersallu123No ratings yet

- Pesticides - Case StudyDocument7 pagesPesticides - Case StudyYusuf ButtNo ratings yet

- Ecophysiology of Pesticides: Interface between Pesticide Chemistry and Plant PhysiologyFrom EverandEcophysiology of Pesticides: Interface between Pesticide Chemistry and Plant PhysiologyNo ratings yet

- 2004 113 1030 Bernard Weiss, Sherlita Amler and Robert W. AmlerDocument9 pages2004 113 1030 Bernard Weiss, Sherlita Amler and Robert W. AmlerPlissken EderNo ratings yet

- Aswath S - Presence of Insecticides and Pesticides in Fruits and VegetablesDocument27 pagesAswath S - Presence of Insecticides and Pesticides in Fruits and VegetablesSaaivimal SNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Pesticide Exposure and Child NeurodevelopmentDocument14 pagesNIH Public Access: Pesticide Exposure and Child NeurodevelopmentFinaNo ratings yet

- InseciticidasDocument1 pageInseciticidasAditi WatNo ratings yet

- ABC T: B D: S OF Oxicology Asic EfinitionsDocument4 pagesABC T: B D: S OF Oxicology Asic EfinitionsLaura ElgarristaNo ratings yet

- Paper Animal EcologyDocument18 pagesPaper Animal EcologyMuthiaranifsNo ratings yet

- Pesticide Effects ReviewDocument39 pagesPesticide Effects ReviewC Karen StopfordNo ratings yet

- High Pesticide Use in India Health Implications - Health Action August 2017 1Document6 pagesHigh Pesticide Use in India Health Implications - Health Action August 2017 1Yashasvi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Acute Pesticide PoisoningDocument46 pagesAcute Pesticide PoisoningGiaToula54No ratings yet

- Week 8 PesticidesDocument8 pagesWeek 8 Pesticidesabida waryamNo ratings yet

- Environmental Contaminants and Medicinal Plants Action on Female ReproductionFrom EverandEnvironmental Contaminants and Medicinal Plants Action on Female ReproductionNo ratings yet

- Pesticide Effect For Subjective Health EffectDocument9 pagesPesticide Effect For Subjective Health Effectkesling sukanagalihNo ratings yet

- Effect of PesticideDocument6 pagesEffect of PesticideseimensemmerNo ratings yet

- Effect of Endocrine Disruptor Pesticides: A ReviewDocument39 pagesEffect of Endocrine Disruptor Pesticides: A ReviewBinu GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Uloe AnswersDocument5 pagesUloe AnswersJohn Mark MadrazoNo ratings yet

- Review of LiteratureDocument25 pagesReview of LiteratureClaire Tejada-montefalcoNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Environmental HealthDocument8 pagesFinal Paper Environmental Healthapi-259511920No ratings yet

- Seeing New Horizons: A Blind Aviator’s Journey After TragedyFrom EverandSeeing New Horizons: A Blind Aviator’s Journey After TragedyNo ratings yet

- Lecture (2) 2022-2023Document8 pagesLecture (2) 2022-2023adham ahmedNo ratings yet

- Pesticide ResiudeDocument6 pagesPesticide ResiudeNamra ImranNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1-2 Toxicology PDFDocument12 pagesLecture 1-2 Toxicology PDFShah MehboobNo ratings yet

- Mechanism of the Anticancer Effect of PhytochemicalsFrom EverandMechanism of the Anticancer Effect of PhytochemicalsNo ratings yet

- RichardStanwick TyeArbuckle ExpertDocument8 pagesRichardStanwick TyeArbuckle ExpertuncleadolphNo ratings yet

- Q & A Information About Toxins and Liquid Zeolites 21ppDocument21 pagesQ & A Information About Toxins and Liquid Zeolites 21ppAna LuNo ratings yet

- Use of ChemicalsDocument50 pagesUse of ChemicalsTaraka nadh Nanduri100% (1)

- GE15 ULOeDocument5 pagesGE15 ULOeKyle Adrian MartinezNo ratings yet

- 0000 - An Introduction To ToxicologyDocument21 pages0000 - An Introduction To ToxicologyStella SamkyNo ratings yet

- Modul EnglishDocument2 pagesModul EnglishdwichaNo ratings yet

- Mold Illness Diet: A Beginner's 3-Week Step-by-Step Guide to Healing and Detoxifying the Body through Diet, with Curated Recipes and a Sample Meal PlanFrom EverandMold Illness Diet: A Beginner's 3-Week Step-by-Step Guide to Healing and Detoxifying the Body through Diet, with Curated Recipes and a Sample Meal PlanNo ratings yet

- Diseases of Fruit Crops in AustraliaFrom EverandDiseases of Fruit Crops in AustraliaTony CookeNo ratings yet

- Pesticide Exposure, Safety Issues, and Risk Assessment IndicatorsDocument18 pagesPesticide Exposure, Safety Issues, and Risk Assessment Indicatorsdiana patricia carvajal riveraNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Toxicology: Sri Hainil, S.Si, M.farm, AptDocument39 pagesFundamentals of Toxicology: Sri Hainil, S.Si, M.farm, AptlyanaNo ratings yet

- AlbertoDocument14 pagesAlbertomonsterrider135No ratings yet

- Concerns Regarding The Safety and Toxicity of Medicinal PlantsDocument6 pagesConcerns Regarding The Safety and Toxicity of Medicinal PlantsMha-e Barbadillo CalderonNo ratings yet

- Chemistry ReportDocument16 pagesChemistry ReportNischal PoudelNo ratings yet

- Potatoes and PesticidesDocument31 pagesPotatoes and Pesticidesapi-249411091No ratings yet

- Assigment Pesticides (FULL)Document13 pagesAssigment Pesticides (FULL)Yana NanaNo ratings yet

- Possible Risk Effect of Nopest® Pesticide Exposure On Non-Target OrganismDocument8 pagesPossible Risk Effect of Nopest® Pesticide Exposure On Non-Target OrganismInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- CSM Molly 2020Document10 pagesCSM Molly 2020Bright Kasapo BowaNo ratings yet

- W13 Environmental Risk - PPTDocument26 pagesW13 Environmental Risk - PPTelforest07No ratings yet

- Exposing the Dangers and True Motivations of Conventional Medicine: A Summary of the Most Commonly Misdiagnosed Illnesses of Modern MedicineFrom EverandExposing the Dangers and True Motivations of Conventional Medicine: A Summary of the Most Commonly Misdiagnosed Illnesses of Modern MedicineNo ratings yet

- Alavanja - 2009 - Introduction Pesticides Use and Exposure Extensive Worldwide-AnnotatedDocument7 pagesAlavanja - 2009 - Introduction Pesticides Use and Exposure Extensive Worldwide-AnnotatedLuisa Fernanda Laverde ChunzaNo ratings yet

- Toxic Tort: Medical and Legal Elements Second EditionFrom EverandToxic Tort: Medical and Legal Elements Second EditionNo ratings yet

- The Necessity of Overcoming The Menace and Dangers of Self Medication SEMINAR 2022Document16 pagesThe Necessity of Overcoming The Menace and Dangers of Self Medication SEMINAR 2022ridwan sanusiNo ratings yet

- Toxicology 2Document8 pagesToxicology 2KEVIN OMONDINo ratings yet

- Environmental Health and ToxicologyDocument15 pagesEnvironmental Health and Toxicologyiah MedelNo ratings yet

- Drug-Induced Oral ComplicationsFrom EverandDrug-Induced Oral ComplicationsSarah CoustyNo ratings yet

- 3rd Exam Environmental ScienceDocument12 pages3rd Exam Environmental Sciencesummerswinter47No ratings yet

- Pesticide Poisoning: 1. Disease ReportingDocument4 pagesPesticide Poisoning: 1. Disease ReportingKhaila PutriNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Infarction PDFDocument5 pagesCerebral Infarction PDFMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Abuse-Related Severe Acute Pancreatitis With Rhabdomyolysis ComplicationsDocument4 pagesAlcohol Abuse-Related Severe Acute Pancreatitis With Rhabdomyolysis ComplicationsMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Akt Extract de PlanteDocument189 pagesAkt Extract de PlanteMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- AmylaseDocument8 pagesAmylaseMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Titlul: Celularitatea Normala Si Patologica La Nivel Gastro-IntestinalDocument2 pagesTitlul: Celularitatea Normala Si Patologica La Nivel Gastro-IntestinalMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- CosmetologieDocument8 pagesCosmetologieMihai Sebastian100% (1)

- Litiază 1Document43 pagesLitiază 1Mihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Preview Book Method-ValidationDocument29 pagesPreview Book Method-ValidationMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Medicina CarteDocument13 pagesMedicina CarteMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Despre ProstataDocument63 pagesDespre ProstataMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Subiectul 1: Nutritie Si Alimentatie Pediatrica (Pag.1028-1030)Document21 pagesSubiectul 1: Nutritie Si Alimentatie Pediatrica (Pag.1028-1030)Mihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Pericardita InfectioasaDocument4 pagesPericardita InfectioasaMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- OsteoporozaDocument63 pagesOsteoporozaMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Zoxamide Review Romani 2015Document14 pagesZoxamide Review Romani 2015Mihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Gelatin IntroDocument10 pagesGelatin IntroMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- LapteDocument8 pagesLapteMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- Programa Examinare KyokushinDocument12 pagesPrograma Examinare KyokushinMihai SebastianNo ratings yet

- YIC Chapter 1 (2) MKTDocument63 pagesYIC Chapter 1 (2) MKTMebre WelduNo ratings yet

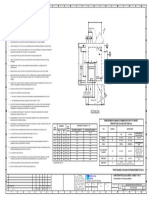

- Notes:: Reinforcement in Manhole Chamber With Depth To Obvert Greater Than 3.5M and Less Than 6.0MDocument1 pageNotes:: Reinforcement in Manhole Chamber With Depth To Obvert Greater Than 3.5M and Less Than 6.0Mسجى وليدNo ratings yet

- Sept Dec 2018 Darjeeling CoDocument6 pagesSept Dec 2018 Darjeeling Conajihah zakariaNo ratings yet

- Bullshit System v0.5Document40 pagesBullshit System v0.5ZolaniusNo ratings yet

- Winter CrocFest 2017 at St. Augustine Alligator Farm - Final ReportDocument6 pagesWinter CrocFest 2017 at St. Augustine Alligator Farm - Final ReportColette AdamsNo ratings yet

- Desktop 9 QA Prep Guide PDFDocument15 pagesDesktop 9 QA Prep Guide PDFPikine LebelgeNo ratings yet

- Out PDFDocument211 pagesOut PDFAbraham RojasNo ratings yet

- Subject Manual Tle 7-8Document11 pagesSubject Manual Tle 7-8Rhayan Dela Cruz DaquizNo ratings yet

- Health Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyDocument3 pagesHealth Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyihealthmailboxNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bengaluru, KarnatakaDocument9 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bengaluru, KarnatakaNavin ChandarNo ratings yet

- 2014 - A - Levels Actual Grade A Essay by Harvey LeeDocument3 pages2014 - A - Levels Actual Grade A Essay by Harvey Leecherylhzy100% (1)

- Music 10 (2nd Quarter)Document8 pagesMusic 10 (2nd Quarter)Dafchen Villarin MahasolNo ratings yet

- NCP - Major Depressive DisorderDocument7 pagesNCP - Major Depressive DisorderJaylord Verazon100% (1)

- Wholesale Terminal Markets - Relocation and RedevelopmentDocument30 pagesWholesale Terminal Markets - Relocation and RedevelopmentNeha Bhusri100% (1)

- Chapter 13 (Automatic Transmission)Document26 pagesChapter 13 (Automatic Transmission)ZIBA KHADIBINo ratings yet

- John L. Selzer - Merit and Degree in Webster's - The Duchess of MalfiDocument12 pagesJohn L. Selzer - Merit and Degree in Webster's - The Duchess of MalfiDivya AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Injections Quiz 2Document6 pagesInjections Quiz 2Allysa MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Book 1518450482Document14 pagesBook 1518450482rajer13No ratings yet

- CV Augusto Brasil Ocampo MedinaDocument4 pagesCV Augusto Brasil Ocampo MedinaAugusto Brasil Ocampo MedinaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 MANA ECON PDFDocument5 pagesModule 2 MANA ECON PDFMeian De JesusNo ratings yet

- Obligatoire: Connectez-Vous Pour ContinuerDocument2 pagesObligatoire: Connectez-Vous Pour ContinuerRaja Shekhar ChinnaNo ratings yet

- EqualLogic Release and Support Policy v25Document7 pagesEqualLogic Release and Support Policy v25du2efsNo ratings yet

- Baseline Scheduling Basics - Part-1Document48 pagesBaseline Scheduling Basics - Part-1Perwaiz100% (1)

- PFEIFER Angled Loops For Hollow Core Slabs: Item-No. 05.023Document1 pagePFEIFER Angled Loops For Hollow Core Slabs: Item-No. 05.023adyhugoNo ratings yet

- Cummin C1100 Fuel System Flow DiagramDocument8 pagesCummin C1100 Fuel System Flow DiagramDaniel KrismantoroNo ratings yet

- In Flight Fuel Management and Declaring MINIMUM MAYDAY FUEL-1.0Document21 pagesIn Flight Fuel Management and Declaring MINIMUM MAYDAY FUEL-1.0dahiya1988No ratings yet

- Synthesis, Analysis and Simulation of A Four-Bar Mechanism Using Matlab ProgrammingDocument12 pagesSynthesis, Analysis and Simulation of A Four-Bar Mechanism Using Matlab ProgrammingPedroAugustoNo ratings yet

- Produktkatalog SmitsvonkDocument20 pagesProduktkatalog Smitsvonkomar alnasserNo ratings yet

- 01 托福基础课程Document57 pages01 托福基础课程ZhaoNo ratings yet

- ISO 27001 Introduction Course (05 IT01)Document56 pagesISO 27001 Introduction Course (05 IT01)Sheik MohaideenNo ratings yet