Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Insurance Contract Essentials

Uploaded by

Ma Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Insurance Contract Essentials

Uploaded by

Ma Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagCopyright:

Available Formats

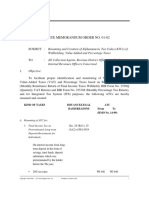

- 1-

1

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

MATTERS TO STUDY:

For purposes of the bar, study very well the following:

1. Insurable interest (most important)

2. The principle of indemnity, specially in property insurance

3. The principle of subrogation (Art. 2207, NCC)

4. The principle of utmost good faith

5. The principle of insurance as a contract of adhesion

CASE: ENRIQUEZ VS. SUN LIFE ASSURANCE CO.

FACTS: An application for life insurance was mailed. An acceptance was also mailed by

the insurer. Before the receipt of the acceptance letter, the insured died.

HELD:

Follow the Theory of Cognition. A contract is perfected upon knowledge

of the acceptance. There was no perfected contract since it was not shown that the

acceptance of the application ever came to the knowledge of the applicant.

HISTORY:

1. Insurance Act (2427)

2. PD 612

3. PD 1460 - merely codified all the insurance laws of the Philippines; date of

effectivity - 11 June 1978

4. PD 1814 - amending certain provisions of the Insurance Code

5. BP 874

CONTRACT OF INSURANCE

A "contract of insurance" is an agreement whereby one undertakes for a

consideration to indemnify another against loss, damage or liability arising

from an unknown or contingent event.

It is an agreement, a contract. Hence, it must have all the essential elements

of a contract: consent, object, and cause or consideration.

What are the essential elements of a contract of insurance? There must be

a subject matter in which case there must be an insurable interest,

especially in property insurance. There must be the risk or the peril insured

against. Under the Code, the risk is any contingent and unknown event, whether

past or future, which may damnify a person having an insurable interest can be

insured against.

Insurable interest is a very important concept in insurance. There must be

a risk or peril insured against. There must also be the consent of the contracting

parties. As a rule, it is a voluntary contract. The only exception is found in

Chapter VI, the Compulsory Motor Vehicle Liability Insurance. Those who have cars

know this. You cannot register your vehicle unless it is covered by this type of

insurance.

-1-

- 2-

2

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

But as a rule, insurance is a voluntary contract. So the parties must give

their consent freely; no vice of consent, like force, intimidation, undue

influence, mistake, violence, etc. Then, like any other contract, there must

be a meeting of the minds. It is a consensual contract; it is perfected by mere consent.

There is also an offer and an acceptance between the insurer and the insured. These

elements must concur before you have a contract of insurance.

Who are the parties? The insured and the insurer. Who is the insurer? He is

the party who undertakes to indemnify the insured against loss, damage or

liability arising from an unknown or contingent event. The insured on the other hand,

is the party to be indemnified upon the occurrence of the loss. Aside from being

capacitated to enter into a contract, what other qualifications must the insured

posses? The law says under Sec. 7, he must not be a public enemy. The law says anyone

except a public enemy can be insured against.

What does public enemy mean? To what does it refer? It refers to a country

with which the Philippines is at war and the citizens thereof. What is the reason why,

under the law, a public enemy cannot be insured against? The reason is obvious. The

purpose of war is to cripple the power & exhaust the

resources of the enemy. If the Code did not contain the aforementioned prohibition,

it could be insured to compensate by way of insurance after having destroyed or

crippled the resources of the enemy.

May a minor validly enter into a contract of insurance? Under the present

Code, the law by way of exception provides that a minor may enter into a contract of

life, health and accident insurance, provided the beneficiary is

among those mentioned under the law: the minor's estate, the parents,

spouse, children, siblings (Sec. 3[3]).

Consider, however, RA 6809, which reduced the minority age to eighteen. So

when the law speaks of a minor at least eighteen years of age, considering RA

6809, I believe that said provision of the Insurance Code has been correspondingly

modified by said piece of legislation.

In other words, one who is eighteen (18) years of age is no longer a minor

under RA 6809. Therefore, a person who is eighteen years of age may enter not

only into a contract of life and accident insurance, but even property

insurance.

Suppose the insured is minor, below eighteen years of age, say seventeen

and he enters into a contract of property insurance. The insurance company issues a

policy. There is a loss by fire. Can the insurance deny the claim on

the ground that the insured is a minor? May the insurer raise as a defense the minority

of the insured, and therefore consider the contract void? NO. Recall the law on

contracts under the Civil Code. Under the law, a contract

entered into by a minor is not void, it is only voidable, therefore valid until

annulled (Art. 1390 [1], NCC)

Furthermore, we have that law on contracts, that when one of the parties

is incapacitated, the capacitated party cannot invoke as a defense the incapacity of

the other party. In other words, in the absence of misrepresentation on the part of

the minor, the insurer will be liable despite the fact that the insured is a minor.

We can even apply the principle

of estoppel. The insurer is estopped from denying the claim.

-2-

- 3-

3

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

How about a married woman? Can she enter into a contract of insurance

without the consent of her husband? YES provided that the insurance is on her

life or that of her children (Sec. 3, par. 2, ICP)

The law does not mention property insurance. Under the Civil Code and under the

present Family Code, with respect to the question of whether a wife

may engage in any trade, occupation or profession without the consent of the

husband, the rule is YES, the wife can do so. All that the wife can do is to

object on serious moral grounds and provided that his income is sufficient

to support the family in accordance with its social standing.

There are many important concepts referring to a contract of insurance. The most

important ones are:

1. it is a personal contract

2. it is a contract of adhesion

CHARACTERISTICS OF A CONTRACT OF INSURANCE

1.

It is an aleatory contract

Art. 2010, NCC - by an aleatory contract, one of the parties or both reciprocally

bind themselves to give or to do something in

consideration of what the other shall give or do upon the happening of

an event which is uncertain or which is to occur at an indeterminate time.

Event which may or may not happen - fire

Even that will happen although we do not know when

- death (in so far

as the insurer is concerned, the even is conditional, it may or may not

happen)

2.

It is a personal contract

See Sec. 20

The law presumes that the insurer considered the personal qualifications of

the insured.

3.

It is a contract of indemnity (except life & accident insurance where the result

is death)

In so far as property insurance is concerned. The purpose of the insurance

contract is to indemnify. Therefore, the amount to be recovered should never

be more than the loss. Otherwise, the contract becomes an instrument for

unjust enrichment (solutio indebiti).

4.

It is a contract of adhesion

A contract which does not result from the negotiation of the parties.

In insurance, there is a policy, normally in printed form. Normally, the

applicant of the insured has no participation in the preparation of

the contract. He may either accept or reject the contract.

-3-

- 4-

4

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

In transportation law, there is a case involving a plane ticket which the

Supreme Court held as a contract of adhesion. Will it bind the passenger

although he has not read it? Yes, because while it is a contract of adhesion, it

is not a void contract. It follows that he is

bound by the provisions thereof. That is also the case of a contract of

insurance.

The situation is different in a contract of sale where the parties normally

would have a say on the terms thereof, the manner of payment,

the manner of delivery, who should shoulder the expenses, etc. This does not

apply in a contract of insurance.

In a contract of insurance, the policy is in written form presented to the

applicant. He either adheres (that is why it is called a contract

of adhesion) or rejects the contract. Therefore, as a result, being a contract

of adhesion, the rule is: should there be any doubt, ambiguity

or obscurity, in any of the terms and stipulations of the contract, the

same shall be interpreted strictly against the insurer and liberally in

favor of the insured.

There is a similar provision of the Civil Code, under Art. 1377.

Art. 1377. The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in

a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity.

Applying the aforesaid provision to a contract of insurance, who is that

party? The insurer. The party who prepared the contract. Therefore,

should there be any doubt, any ambiguity or obscurity, in any of

terms and conditions of the contract, the

rule shall be interpreted strictly against

the favor of the insured.

the

to follow is: the same

insurer and liberally in

To illustrate: regarding the so-called authorized driver clause of the

policy, who is deemed to be an authorized driver under the policy? In a

contract of insurance, should there be an accident, and the driver at the time

of the accident is not an authorized driver within the meaning

of the policy, there can e no recovery.

Under the policy, who is an authorized driver?

1. the insured

2. any person driving upon the insured's order with his permission

provided the person driving is authorized to drive the motor vehicle

in accordance with the licensing laws, rules, or regulations and is

not disqualified from driving the same by order of a court law, or

any rule or regulation on that behalf.

Simply that means: if the one driving is other than the insured:

1. he must be authorized or permitted by the insured.

2. he must be qualified to drive in accordance with, say, the Land

Transportation Code, and other rules and regulations, must not have

been disqualified by any court of law, rule or regulation in that behalf.

According to the Code, however, the requirement that the person driving,

must be duly authorized to drive in accordance with the licensing law,

rules and regulations, and is not disqualified from driving the

-4-

said

- 5-

5

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

motor vehicles by any order of a court of law, etc., applies only if the person

driving is other than the insured.

So, in the case of Palermo, and some other cases, at the time of the accident, the

one driving his car was the insured himself. He had an expired driver's license.

The insurance company denied the claim

involving the authorized driver clause. According to the insurance

company, the under the policy, the insured as driver was not authorized,

hence, the insurer was not liable.

The Supreme Court said NO. Because at the time of the accident, the one

driving the car was the insured himself. The foregoing requirement does

not apply.

In the case of Perla Compania de Segurus vs. CA, 208 scra 478, the insured car

was parked somewhere in Makati. It was car napped. It was

being driven by someone who had an expired license before it was stolen.

The insurance company denied the claim invoking the authorized driver clause.

The Supreme Court disagreed. In the first place, what should apply is the theft

clause, not the authorized driver clause. The fact that the person driving the

car before it was stolen did not have a license or

had an expired driver's license is of no moment. The clause that should

apply is the theft clause.

In the case of Villacorta vs. Insurance Commission, 100 SCRA 467, the insured

car was involved in an accident and was brought to the repair

shop. Necessarily the owner would have to entrust the keys of the car

to the owner of the shop or the authorized representative, so the car

after the repair had been completed could be road-tested. But some of the

employees of the motor shop used the car in a joy-ride around

Manila. Unfortunately, it was involved in an accident, again the

insurance company denied the claim invoking the authorized driver clause.

The Supreme Court disagreed. When the insured entrusted the keys to the

owner of the repair shop, there was an implied authority given by the

insured either to the owner of the shop or the latter's employees to drive the

car. Secondly, in that case, what should apply is not the authorized driver

clause but the theft clause of the policy.

EXCEPTION TO THE RULE: tourists, however, who have an expired xxx of 90

days is not under the law, an authorized driver unless he secures a Philippine

Driver's License.

REMEMBER You apply the rule that should there be any doubt, ambiguity or obscurity, in

any of the terms and stipulations of the contract, the same shall be

interpreted strictly against the insurer and liberally in

favor of the insured, only when there is doubt, ambiguity or obscurity,

in any of the terms and stipulations of the contract.

But if the terms, conditions, and stipulations are clear, there is no room for

interpretation.

-5-

- 6-

6

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

When the law or contract is clear, no matter how harsh it may be, then

the courts will have to enforce the law or contract. Courts are not supposed

to make contracts for the parties. That is also true with the

contract of insurance.

Why don't we refer or apply to the provisions of the Civil Code when we

talk about the contract of insurance? What laws govern the contract of

insurance?

Art. 2011, CC: The contract of insurance is governed by special laws.

Matters not expressly provided for in such special laws shall

be regulated by this Code.

Primarily, a contract of insurance is governed by special laws (PD 1460,

as amended). In the absence of any applicable provision of the special

law, the provisions of the Civil Code, particularly the provisions on

Obligations and Contracts shall be applied.

In the absence of any applicable provisions in both, then decisions and

doctrines prevailing in the United States may be applied. Why? Because

primarily, our law on insurance is of American origin, patterned from the

insurance laws of California and New York.

REMEMBER, in resolving insurance problems, apply the following in the order

they are mentioned:

1. Special Laws

2. Civil Code (Art. 2011)

3. American decisions and doctrines

5.

It is based on the principle of subrogation (applicable only to property

insurance)

Art. 2027, CC: If the plaintiff's property has been insured, and

he has received indemnity from the insurance company for the

injury or loss arising out of the wrong or breach of contract

complained of,

the insurance company shall be subrogated to the rights of the insured

against the wrongdoer or the person who has violated the contract. If the

amount paid by the insurance company does not fully cover the injury or

loss, the aggrieved party shall be entitled to recover the deficiency

from the person causing the loss

or injury.

Subrogation is

essentially a process of substitution, where the subrogee,

in this case, the insurer, steps into the shoes of the insured. Actions or

rights pertaining to the insured will be transferred to the insurer.

For example, you have a car insured under a comprehensive policy. It was

involved in an accident. It was the fault of the other party. Damage:

P30,000.00. What are your remedies? Either you recover from the insurer or

from the party at fault. You cannot recover from both. Why

not? Because a contract of insurance is a contract of indemnity. It is

not to be used as an instrument for profit or gain.

Suppose you decide to recover from the insurer, but the insurer pays you only

P25,000.00. With respect to that amount, there will be subrogation. It is now

the insurer who can recover this amount from the

-6-

- 7-

7

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

party at fault. In the case of Malayan Insurance Company, the court held that

subrogation is a normal incident of indemnity insurance. It inures to the

insurer without the need of formal assignment or an express stipulation in the

policy to that effect. The moment the insurer pays the insured, the insurer

becomes a subrogee in equity.

May the insured recover from the party at fault? Art. 2207 of the Civil

Code says YES, because the law says, "if the amount paid by the insurance

company does not fully recover the injury or loss, the

aggrieved party shall be entitled to recover the deficiency from the person

causing the loss or injury."

Can the insurer's right of subrogation be destroyed? Yes. The insurer's right

of subrogation can be destroyed when the insured releases the other party at

fault from liability. Why? Because by releasing the other party, the insured

destroys or defeats the insurer's right of subrogation. Hence, the insurer

will deny the claim of the insured.

In other words, it is the obligation of the insured to preserve at all

times that right of recovery which belongs to him, but which will eventually

be transferred to the insurer by way of subrogation. That is

a condition in the insurance policy.

How else can the right of subrogation be destroyed or defeated? When the

insurer pays the insured even if the cause of the loss was not the

risk or peril insured against.

What factors must concur before there can be recover in property

insurance?

1. the insured must have an insurable interest in the subject matter;

2. that the interest must be properly covered by the policy;

3. there must be a loss; and

4. as a rule, the loss must be proximately caused by the peril insured

against.

ILLUSTRATIONS:

1.

A owns a house worth P1M. He has an insurable interest in the house.

But B insured the house in his name. Should there be a loss, can B

recover? No. Because he has no insurable interest in the house. Can

A recover? No. Because while A has an insurable interest in that house,

such interest was not covered by the policy, as it was B who

insured the house.

2.

In the same example, A insured the house against fire for one year.

During the year, there was no fire, there was no loss. Can there be

a refund of the premiums paid? No. there can be no recovery. What does the

insured get? What is the consideration?

The consideration on the part of the insurer is the premium paid by

the insured. How about the insured, what is its consideration? The

protection, the promise, the undertaking on the part of the insurer

to indemnify the insured in case of loss. That is the consideration

on the part of the insured.

-7-

- 8-

8

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

So it is not correct to say that should there be no loss within the

term of the policy, there is no cause or consideration. There was a

consideration. If there is no cause or consideration, even under

the law on contracts, the contract is void. Or where the cause or

consideration is illicit or unlawful, the contract is also void.

Art. 1411, CC: When the nullity proceeds from the illegality of the

cause or object of the contract, and the act constitutes a criminal

offense, both parties being in pari delicto, they shall have no action

against each other, and both shall be prosecuted. xxx

INSURABLE INTEREST

When is a person said to have an insurable interest in a subject

matter? Why does the law require the insured to have an insurable interest?

If the insured has no insurable interest in the subject matter, the contract

becomes a wagering contract, on the theory that he has nothing to lose and everything

to gain.

While it is true that the insurance is a conditional contract based on chance, it

is not the same as a wagering contract. The law does not authorize

it under Sec. 4, 16 and 25.

When is the insured deemed to have an insurable interest? A person has an

insurable interest in the subject matter if he is so connected, so situated,

so circumstanced, so related, that by the preservation of the property he shall

suffer pecuniary loss, damage or prejudice.

How do we determine whether a person has an insurable interest in the life

of another person, without considering the enumeration under Sec. 10? There is

insurable interest when that person has an interest in the preservation of

life of another despite the insurance, rather than in its destruction

because of the insurance.

In other words, could the

beneficiary be more interested in terminating

that life so that he could

recover from the insurer, or could he be more life,

interested in preserving that

despite the insurance, then he has

insurable interest in that life.

In whose life or health does a person has an insurable interest?

Sec. 10. Every person has an insurable interest in the life and health:

a) of himself, of his spouse and of his children;

b) of any person on whom he depends wholly or in part for education or

support, or in whom he has a pecuniary interest;

c) of any person under a legal obligation to him for the payment of money, or

respecting property or services, of which death or illness might delay or

prevent the performance; and

d) of any person upon whose life any estate or interest vested in

him depends.

The explanations for (a) and (b) above are self-explanatory.

-8-

- 9-

9

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

For (c) above, this refers to a case where the person in question is under

obligation either for payment of money or to render services. The movie companies

for instance, have insurable interest in the life/lives and health

of the actors and actresses who are under contract with them. Why? Because these

actors and actresses are under obligation to render services to said movie companies.

Without these actors and actresses, these movie companies are liable to close down.

With respect to the obligation for the payment of money, there is the creditordebtor relationship. A creditor has insurable interest in the life of the debtor, but

only to the event of the obligation. For instance, the debtor owes the creditor of

P1M in the form of a loan. Can the creditor insure the life of the debtor? Yes.

Because the debtor is under obligation to

pay money to the creditor. The death of the debtor will either delay or prevent the

payment of the loan. But although the creditor can insure the life of the debtor,

the insurance is limited to the amount of the loan which

is P1M.

QUERY:

In the example above, suppose C (creditor) insures the life of D (debtor)

for P1M. Before the death of D, the loan had been fully paid by him. Can D recover? No,

because he was not a party to the contract (Art. 1311, CC). An

insurance procured by the creditor over the life of the debtor for the benefit of the

creditor will not inure to the benefit of the debtors. The creditor is not acting as

an agent. Can C recover? No, because he no longer

had insurable interest on the life of D at the time of D's death. Who can recover?

Nobody.

Suppose it was D who insured his own life and made C as the beneficiary,

but before D's death, the loan had been paid in full, this time who can recover? The

heirs or legal representative of D.

Try to consider the difference between those two different situations. An

insurance procured by the creditor on the life of the debtor in the name or for

the benefit of the creditor will not inure to the benefit of the debtor.

The nature of the life insurance partakes of the nature of a contract of indemnity

because, unlike in property insurance, in life insurance, as a rule,

there is no limit. That is one of the distinctions between life insurance and

property insurance. You can insure your own life for as much as you wish, with as

many insurance companies as you like, provided you pay the premiums.

In property insurance, on the other hand, there is a limit. And that is the

extent of the insurable interest. Under Sec. 14, for a person to have insurable

interest in property, he need not be the owner thereof.

Sec. 14. An insurable interest in property may consist in:

(a) An existing interest;

(b) An inchoate interest founded on an existing interest; or

(c) An expectancy, coupled with an existing interest in

which the expectancy arises.

that

-9-

out

of

- 10 -

10

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Aside from an owner of a property, who else can have an insurable interest

in such property? A lessee, among others. In order to ascertain whether or not a

person has an insurable interest in property subject matter, the test to be applied is

Sec. 17.

Sec. 17. The measure of an insurable interest in property is the extent

to which the insured might be damnified by loss or injury thereof.

In the event of loss or injury to the property, will he be damnified? Will

he suffer any loss, damage or prejudice? If the answer is YES, then he has insurable

interest.

In the sale of property, the vendor, prior to actual delivery, has an insurable

interest in the property. In sale with a right to repurchase (pacto

de retro), within the period of redemption, the vendor a retro has an insurable

interest in the property because he still has the right of redemption.

Although you should recall how is ownership of the thing sold transfers to

the vendee or buyer. That is important for determining for instance, the issue of who

should bear the loss, because of the principle or res perit domino.

In transfer by delivery, tradition, actually or constructively, it is not

the perfection of the contract, nor the payment of the price, but the delivery, which

will transfer ownership to the buyer. So pending delivery, despite perfection or even

payment of the price, as a rule, then vendor is still the owner. The vendee, of

course, under Arts. 1163 -1165, CC, can demand

delivery. He has a right. So in effect, both the vendor and the vendee

have insurable interest in property subject matter.

With respect to a stockholder of a corporation, does he have insurable interest

in the corporate assets and property? The rule in corporation law is

that a corporation has a personality distinct and separate from those of its

stockholders. Hence, any property of the corporation is not property of its

stockholders. Such property belongs to the corporation as a distinct and separate

entity. But a stockholder has an inchoate interest to the extent of

his shares or subscription in corporate assets. To that extent, a

stockholder has insurable interest in the property of a corporation.

Going back to life insurance, do you have an insurable interest in the life of

your girlfriend? No. Mere relationship is not enough to grant insurable interest in a

person party to such relationship. Unless she depends

on you for support.

What about a corporation, does it have an insurable interest in the life

of its janitor? No. Even if the janitor is under obligation to render services

to the corporation, death of the janitor cannot bring loss or prejudice to the

corporation. But does a corporation have an insurable interest in the life of

its president? Yes. Death of the president will mean

loss or prejudice to the corporation itself.

Do you have an insurable interest in the life of your lecturer? Is he not

under obligation to render service to you (deliver lectures)? Or is it the school

which has an insurable interest in the life of the lecturer? No.

- 10 -

- 11 -

11

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Sec. 8.

Unless

the

policy

otherwise

provides,

where

mortgagor

of

property

effects insurance in his own name providing that the loss shall be payable to the

mortgagee, or assigns a policy of insurance to a mortgagee, the insurance is

deemed to be upon the interest of the mortgagor, who does not cease to be

a party to the original contract, and any act of his, prior to the loss, which would

otherwise avoid the insurance, will have the same effect, although the property is in

the hands of the mortgagee, but any act which, under the contract of insurance, is to

be performed by the mortgagor, may be performed by the mortgagee therein named, with

the same effect as if it had been performed by the mortgagor.

These are the possible situations You have a debtor who owes the creditor P2M. There is a principal

contract of loan, which is secured by a real estate mortgage of a house and

lot, and the house is worth P3M.

Who has an insurable interest in the house and how much? Both the mortgagor

and the mortgagee have separate and distinct interest in that house. Why the

mortgagor? Because he is the owner.

Will the fact that it is mortgaged to the creditor secure a loan of P2M not diminish

or reduce the insurable interest of the mortgagor in the house?

Should not the loan of P2M be deducted from the value of the house which is

P3M, making the mortgagor's insurable interest in the house only up to the extent of

P1M?

No. Despite the mortgage, the mortgagor's interest will be up to the

value of the house. Why? Because 1.

2.

Under the law on Credit Transactions, ownership is not transferred to the

mortgagee, and

Loss of the house will not mean the extinguishment of the loan.

Under the law on Contracts, while

contract will extinguish the accessory

accessory contract will not extinguish

accessory follows the principal.

the extinguishment of the principal

contract, the extinguishment of the the

principal contract. The rule is:

Should the house be lost, such loss will not necessarily mean the

extinguishment of the loan.

The loan will only become an unsecured obligation. Therefore, the

mortgagor's interest in the house remains.

How about the creditor, who is not the owner, will he have an insurable interest in

the house? Yes, because by the loss or destruction thereof shall

prejudice the obligation will become unsecured to the extent of the loan of P2M. Both

mortgagor-debtor and mortgagee-creditor have separate and distinct interest in the

said property.

SITUATION NO. 1:

- 11 -

- 12 -

12

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

D insures the house for P5M against fire in his own name, for his own interest

only. Nothing is mentioned about the interest of C. The house was destroyed by

fire. Who can recover and how much?

Can C recover? No, because he is not a party to the contract of insurance.

Can D recover? Yes. How much? Only P3M although he insured it for P5M.

Why only P3M? Because insurance is a contract of indemnity.

If he were allowed to recover P5M but the property is worth only P3M, D would be

making a profit. That would encourage arson.

While C cannot recover directly from the insurance company, he shall, however,

hold a lien over the proceeds of the policy under Art. 2127, CC.

SITUATION NO. 2:

C insures the house for P2M against fire in his own name, for his own interest.

Nothing is mentioned about D's interest. The house is completely destroyed by fire.

Who can recover?

Only C, because D is not a party to the contract of insurance. If the insurance

company indemnifies C, the amount of P2M, will such payment extinguish the loan?

No. There will be subrogation. The insurer, after indemnifying C can recover

from D. There will be a change of creditors.

SITUATION NO. 3:

What is contemplated under Sec. 8 is where D insures the property in his

name, for his interest, but with a stipulation in favor of C.

The following are the consequences:

1.

2.

D is still the real party in interest, he does not cease to be a

party to the contract.

Any act of D which will otherwise avoid the policy will have the same

effect.

Suppose the policy contains a stipulation that there should be no storage of

flammable materials like gasoline. In violation thereof, D, the insured,

stores gasoline. This is an act of the insured, which under the policy, could avoid

it. Despite the "loss payable clause" in favor of the creditor,

that will avoid the policy.

Suppose, the insurance was for P3M and there was a total loss, who can recover and

how much?

C cannot recover from the insurer because at the time of the loss, he

no longer had any insurable interest in the property.

Suppose, there was no payment, who can recover and how much?

- 12 -

- 13 -

13

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

C can recover P2M and D, 1M. This time the loan is extinguished. There will be no

subrogation. This is what we call "loss payable clause."

PROBLEM:

In life insurance, is it necessary for the beneficiary to have an insurable

interest in the life of the insured?

It depends. Where a person insures his own life, he can, as a rule, designate

anybody, even a complete stranger, as the beneficiary. That beneficiary need

not have an insurable interest in the life of the insured.

He can designate anybody subject only to the exceptions under Art. 739,

CC, in relation to Art. 2012, CC.

"Art. 739. The following donations shall be void:

1. Those made b/n persons who were guilty of adultery or concubinage at

the time of the donation;

2. Those made b/n persons found guilty of the same criminal

offense, in consideration thereof;

3. Those made to a public officer or his wife, descendants and

ascendants, by reason of his office.

In the case referred to in No.1, the action for declaration of nullity may

be brought by the spouse of the donor or donee; and the guilt of the donor and

donee may be proved by preponderance of evidence in the same action."

"Art. 2012. Any person who is forbidden from receiving any donation under

Art. 739 cannot be named beneficiary of a life insurance policy

by the person who cannot make any donation to him, according to this article."

Simply, one who cannot receive any donation under Art. 739, cannot be named

beneficiary in the life insurance policy by the person who cannot give any

donation.

Reason behind the law: to prevent an indirect violation or circumvention of the

law.

Proceeds of a life insurance policy partakes of the nature of a

donation to the beneficiary. Act of liberality.

CASE: INSULAR LIFE VS. EBRADO

FACTS: A married man insured his life and designated his mistress as

beneficiary. When he died, both the wife and the mistress filed their

respective claim with the insurance company.

The insurance company went to the court by way of interpleader.

ISSUE: Who should recover, the wife or the mistress?

HELD:

The mistress could not recover because of Art. 739 and Art. 2012. The

wife could not recover either because she was not a party to the contract; neither was

there a stipulation in her favor. The proceeds would go to the estate of the deceased.

- 13 -

- 14 -

14

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

As a rule, when a person insures his own life, he can designate anybody as his

beneficiary. However, when a person insures the life of another, he must

have an insurable interest in that life. Apply Sec. 10. One cannot just insure the

life of anybody and make himself the beneficiary. He must have an insurable

interest in that life.

In property insurance, however, the insured MUST always have an insurable

interest in the subject matter.

In the case of a mortgage property, the interest of the mortgagor is up to

the extent of the value of the property. The only exception is the bottomry

loan.

The nature of a bottomry loan is that the payment of the loan is conditional,

subject to the safe arrival of the vessel at the port of destination.

PROBLEMS Q: The father insured his life and made his son the beneficiary. Later, the

father discovered that his son was a drug addict. So he wrote to the insurance

company asking for a change of beneficiary, from his son to his wife. The father

died and the son filed a claim with the insurance company, claiming that he, having

been named by his father as the beneficiary in the policy, he acquired a vested

right or interest in the proceeds of the insurance policy. Is the contention of the

son tenable?

A:

is

Under Sec. 11, which reversed the provisions of the old law, the rule now

that the designation is presumed to be revocable. The rule is that

the

insured can always change the beneficiary named in the policy, unless he expressly

waives that right in the policy.

Q:

Can the beneficiary apply the vested interest rule in the policy?

If the designationis irrevocable, like for instance, when there is an

express waiver by the insured in the policy. The beneficiary, in this case, acquires a

vested interest in the policy of which he cannot be deprived without his consent.

Otherwise, in the absence of an express waiver by the insured, the beneficiary can be

changed anytime.

A:

Q: What is the effect under Sec. 12 where the beneficiary in life insurance

policy willfully brings about the death of the insured, either accomplice

or accessory?

A: The beneficiary automatically forfeits his interest in the insurance policy.

This does not mean, however, that the insurer will no longer be liable. The insurer

remains liable, the only effect is that the beneficiary's interest is forfeited.

Who then will be entitled to the proceeds? The nearest relative of the insured, not

otherwise disqualified (so, where the beneficiary brings about the death of the

insured not in a willful manner, as

for instance, through reckless imprudence under Art. 365, RPC, Sec. 12 does not

apply).

- 14 -

- 15 -

15

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Q: Is a mere hope or expectancy insurable? Suppose a person buys sweepstakes

tickets and insures his chance of winning, so much so that if he does not win

the first price, the insurer will indemnify? Or can you insure your chance of

passing the bar exams?

A: No. A mere hope or expectancy is not insurable. This is a wagering contract.

In order that a mere hope may be insurable, it must be coupled with

an existing interest in the thing from which the expectancy shall arise under

Sec. 14, par. c. or under Sec. 16, which provides that there must be a valid

contract.

The shattering of expectation, however bright, or the disappointing of hope,

however strong, does not constitute such a loss to be indemnified by insurance. It

will be in the nature of a wagering contract which the law does

not allow - gambling.

Q: The mother was confined in a hospital, scheduled to be operated on the following

day of a very serious illness. The night before the operation, she

called for her only son, and told him that she had prepared a will naming the son

as the only heir. Among the property that the son expected to inherit was a house

located at Dasmarias Village. On the same evening, the son together

with his family moved into the house which he expected to inherit. At the same time

he insured the house in his name against fire. The operation took

place, and unfortunately, the mother died. After which, the house was

completely destroyed by fire, the risk or peril insured against. May the son

recover?

A: No. When he insured the house, he had no insurable interest. His interest

was a mere hope or expectancy. You do not inherit from a person who is still

alive. Inheritance takes place upon the death of the decedent. Under the

law, insurable interest in property must exist both at the time of the

effectivity of the policy AND at the time of the loss, although it need not

exist in the meantime.

Insurable interest in life, on the other hand, need to exist only at

the time of the effectivity of the policy, it need not exist thereafter.

Q: Under Sec. 20, where there is a change of interest in any part of the thing insured

unaccompanied by a corresponding change of interest in the insurance, what will

happen?

A:

The policy shall be suspended to an equivalent extent until the interest

in the thing and the interest in the insurance are vested in the same perso n.

Under Sec. 58, the mere transfer of the thing insured will not mean automatic

transfer of the policy. It shall be suspended until the same person becomes the owner

of both the policy and the thing insured. It will merely be suspended, it will not be

avoided, because of the rule that insurable interest in property must exist both at

the time of the effectivity of the loss although it need not exist in the meantime.

EXAMPLE:

- 15 -

- 16 -

16

REVIEW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

You own a car, and insured it in your name. At the time of the effectivity of

the policy there is no question that you have an insurable interest in the car

being the owner. The policy is for a term of one year. Six months

thereafter, you sold the car. There is a change of interest in the car, from the

original owner to the buyer. But the policy was not transferred

to the buyer. Thereafter, the car was lost. Who can recover? Nobody. Neither

the original owner nor the buyer. The original owner cannot recover because

while he had an insurable interest in the car at the time

of the effectivity of the policy, he no longer had insurable interest in

the car at the time of the loss. He had sold it. The buyer could not recover

either. While he had insurable interest at the time of the loss,

he had no insurable interest in the car at the time of effectivity of the

policy.

Q: How can insurable interest in both the insured and the policy be vested again in

the same person?

A: (1) In the example given, before the occurrence of the loss, the policy was

transferred to the buyer. In that case, may the buyer recover? Yes, because when the

policy was transferred to him, interest in both the policy and in the car were present

in the buyer.

(2) Where the seller repurchases the car before the occurrence of the

loss. In which case, the seller may recover.

So, if you sell an insured property and neither you nor the buyer takes the

precaution of having the policy transferred in the name of the buyer, in

case of loss, neither you and the buyer can recover. This is because of the

rule in property insurance that, insurable interest must exist at the time of the

effectivity of the policy and at the time of the occurrence of the loss.

In life insurance, however, all that the law requires is that insurable interest

must exist at the time of the effectivity of the policy but it need

not exists thereafter.

EXAMPLE:

A corporation has insurable interest in the life of its president. So here is

a corporation which insures the life of its president. The corporation is the

beneficiary. As president of the corporation, he is allowed to use

a house belonging to the corporation. After the effectivity of the life insurance

policy, the president resigns from the corporation and relinquishes all his

interest in the corporation. after which, he insured

the house in his own name against fire. After resigning and insuring the

house, the corporation agrees to sell the house to its former president.

Then the former president dies, and the house burns.

Q: Who can recover on the life insurance policy?

A: The corporation can, because at the time of the effectivity of the

policy, the corporation still has an insurable interst in the life of

the president, because he was still president then. Although at the time of

the loss (death), the corporation no longer had insurable interest in the

life because he had already resigned.

- 16 -

- 17 -

17

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Q: Who can recover on the fire insurance?

A: Neither the corporation nor the former president (estate) can recover,

because when the president insured the house in his name, he

did not yet have an insurable interest in the house for the simple reason that

he was not yet its owner. It was after the effectivity of

the policy that he was able to buy it.

INSURABLE INTEREST IN LIFE vs. INSURABLE INTEREST IN PROPERTY:

Insurable interest in life need exist only at the time of the

effectivity of the policy. It need not exist thereafter.

Insurable interest in property must exist both at the time of the

effectivity of the policy AND at the time of the loss. It need not exist in

the meantime.

SUSPENSION OF POLICY

GENERAL RULE:

Sec. 20.

xxx

change

of

interest

in

any

part

of

thing

insured

unaccompanied by a corresponding change in interest in the insurance,

suspends the insurance to an equivalent extent, until the interest in the

thing and the interest in the insurance are vested in the same person.

EXCEPTIONS:

Under the following circumstances, the policy will not be suspended despite

a change in any part of the thing insured:

1.

Sec. 21. A change in interest in a thing insured, after the

occurrence of an injury which results in a loss, does not affect

the right of the insured to indemnity for the loss.

In motor vehicle insurance, the owner insured his car in his name.

It was involved in an accident. Damage: P20,000.00. After which, he

sold the car. May the seller recover? Yes, because at the time of the

occurrence of the loss (accident) he was still the owner, hence,

he still had an insurable interest in the car. But suppose after the transfer

or sale of the car, a second accident happened, however, there was no

transfer of the policy to the buyer. With respect to the second accident, who

can recover? Nobody, because neither the seller nor the buyer had insurable

interest both at the time of the effectivity of the policy and at the time of

the loss.

2.

Sec. 22. A change of interest in one or more several distinct things,

separately insured by one policy, does not avoid the insurance as

to the others.

This refers to a divisible contract. You own four houses in a compound: A,

B, C, and D. You insured them under one policy, but separately valued. You

pay a single premium. Later, you sold house A,

but the policy was not transferred to the buyer. Afterwards, house B

- 17 -

- 18 -

18

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

was burned down. Can the insured recover? Yes, the sale of house A

will not affect the insured's right to be indemnified because of the

loss or destruction of house B. Although they are covered under the

policy and a single premium is paid, the contract is divisible.

3.

Sec. 23. A change on interest, by will or succession, on the death of

the insured, does not avoid an insurance; and his interest in the

insurance passes to the person taking his interest in the thing insured.

Whoever takes the property of the decedent will automatically become the

owner of the policy. Here is a father, who, during his lifetime,

insured his house in his name against fire. The policy was in the name of the

father. The house was later inherited by the son. So actually, there was a

change of interest in the house, from the father to the son. Later, the house

was burned. Can the son recover?

Yes. Whoever takes the house will automatically be the owner of the

policy.

What is the reason for this exception?

Art. 1311, NCC. Contracts take effect only between the parties, their

assigns and heirs, except in cases where the rights and obligations

arising from the contract are not transmissible by their

nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law. The heir is not liable

beyond the value of the property he received from the decedent.

4.

Sec. 24. A transfer of interest by one of several partners,

owners, or owners in common, who are jointly insured, to the others,

does not avoid an insurance even though it has been agreed that

the insurance shall cease upon an alienation of the thing insured.

joint

This refers to a case where the change of interest is made in favor

of a partner, joint owner, or co-owner. Let's say A, B, and C are owners in

common of a house worth P3M. They insured the house jointly in their names.

Later, A sold his undivided share of to D, after which the house was

completely destroyed by fire. Insofar as the share of A is concerned, there

had been a change of interest in favor of D. Since D is a stranger, not a

partner, the rule in suspension is applied. When is the exception applied? The

exception is applied where A, instead of transferring his share to

D, transfers the same to B or C, thereby increasing the participation of

either to . There will be no suspension of the policy because no

new party was introduced to the co-ownership.

5.

Sec. 57. When a policy is so framed that it will inure to the benefit of

whomsoever, during the continuance of the risk, may become the owner of

the interest insured.

This contemplates a situation where there is an agreement or

stipulation in the policy that should there be a transfer or change

of interest in the property, there should likewise be an automatic transfer

or policy. This is a valid stipulation.

- 18 -

- 19 -

19

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Art. 1306, NCC. The contracting parties may establish such

stipulations, clauses, terms, and conditions as they may deem

convenient, provided they are not contrary to law, morals, good

customs, public order or public policy.

Sec. 25. Every stipulation in

policy

of insurance

for the payment of

loss

whether the person insured has or has not any interest in the property insured,

or that the policy shall be received as proof of such interest, and every policy

executed by way of gaming or wagering, is void.

So even if there is a stipulation, that it is void, or that the policy shall be

received as evidence of proof of interest. This is also void.

As to whether a person has or has no insurable interest in property, cannot be

vested by mere agreement or stipulation or the parties. It is contrary to law (Sec.

25) and public policy because it becomes a wagering contract.

PROBLEM:

Q: B is not the owner of the house. He is neither a lessee nor a mortgagee. He

has nothing to do with the house. He tells the insured that despite the fact

that he has no insurable interest in the house, he would

like to insure the house in his name against fire. He is willing to pay any amount

of premium that may be required from him. And the insurer knowing that B has no

insurable interest in the house, agrees to issue a

policy to B. they further stipulated that should the house be destroyed by

fire, the insurer will indemnify him regardless of whether or not he has

insurable interest in the house. Afterwards, the house is completely

destroyed by fire. Can B recover?

A: No. Their agreement is contrary to law and public policy, because it was a

wagering contract.

UTMOST GOOD FAITH (UBERIMEI FIDEI)

The contract is the law between the contracting parties, and they are enjoined

to comply with it in good faith. In a contract of insurance, the law

does not require only ordinary good faith but utmost good faith.

What is utmost good faith? It means absolute and perfect candor, openness and

honesty. It is the absence of any deception or concealment however slight.

The parties to a contract of insurance must act in utmost good faith. There

should be no concealment. There should be no misrepresentation. What is

the reason for utmost good faith? A contract of insuranc

e is an aleatory

contract.

By an aleatory contract, one or both of the contracting parties reciprocally bind

themselves to give or to do something in consideration of what the other party shall

give or do.

- 19 -

- 20 -

20

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Being an aleatory contract, the insurer's liability is conditional. The

parties, especially the insurer, relies on the representation and statements

made by the other party. In life insurance, the insurer will not just issue a

policy. The insured may be asked to give statements or to answer questions. The

insured, next to his doctor, is in a better position to know the state of

his health. So he should not in any way misrepresent the state of his health.

WHAT ARE THE DEVICES USED BY THE INSURER TO ASCERTAIN, DETERMINE AND CONTROL

THE RISKS TO BE ASSUME?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Concealment

Representation

Warranties

Conditions

Exceptions

WHAT ARE THE FOUR PRIMARY CONCERNS OF THE INSURER?

1. The correct estimation of the risk, which enables the insurer to decide

whether he is willing to assume it and if so, at what rate of premium.

2. The precise delimitation of the risk which determines the extent of the

contingent duty to pay undertaken by the insurer.

3. Such control of the risk after it is assumed as will enable the insurer to

guard against the increase of the risk because of change in

conditions.

4. Determining whether a loss occurred and if so, the amount of such loss.

HOW MAY AN INSURER BE ABLE TO CONTROL THE RISK THROUGH THE USE OF EXCEPTION?

Exempt certain properties

Except certain perils or risks

IN PROPERTY INSURANCE, THE FOLLOWING MUST CONCUR BEFORE ONE MAY RECOVER:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Insurable interest;

Interest must be properly covered by the policy;

There was a loss; and

Loss must be proximately caused by the peril insured against.

The principle of utmost good faith applies to both parties. If information is

withheld, then it follows that there was no meeting of the minds.

CONCEALMENT

Sec. 26. A neglect to communicate that which a party knows and ought to communicate

is called concealment.

- 20 -

- 21 -

21

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

I would call it a "sin of omission," neglect, failure. Where you are dutybound to communicate to the insurer, an information or a fact which is within

your knowledge, which is material in the contract, but which you did not communicate,

you are guilty of concealment under Sec. 27. The remedy of the insurer is to rescind

the contract.

Sec. 27. A concealment whether intentional or unintentional entitles the injured

party to rescind a contract of insurance. (As amended by Batasang Pambansa Blg.874)

What are the grounds for rescission?

1. Concealment

2. Misrepresentation, and

3. Breach of warranty.

When we speak of rescission, the party asking for rescission of the contract

impliedly admits the existence of a valid and binding contract. Because the purpose

of rescission is to terminate, to rescind. You do not terminate or rescind a nonexisting contract. Rescission would not be the remedy. So rescission presupposes the

existence of a valid ad binding contract.

Going back to concealment, does it mean that the parties are also required

to communicate everything, including "tsismis," especially where the applicant is

a woman? No. What one is required to communicate is that which is within his

knowledge. It must be material. One is not under obligation to communicate

something immaterial.

How is materiality determined?

Sec. 31. Materiality is to be determined not by the event, but solely by

the probable and reasonable influence of the facts upon the party to

whom the communication is due, in forming his estimate of the

disadvantages of the proposed contract, or in making his inquiries.

For an information to be material, is it necessary that it be the cause of

the loss? No. In determining whether or not an information is material, you simply ask:

"Had this been concealed to the insurer, had it not been concealed, do you think the

insurer would have been influenced (1) in deciding or not whether to issue the policy

and (2) in determining the rate

of premium?" If the answer is yes, then it is material.

For example, here is a person suffering from a terminal disease, confined in

a hospital. The doctors told him about it and he had, at most six months to live.

Wanting to provide something for the members of his family upon his

death, he went to an insurance company and applied for a life insurance policy. The

insurance company agreed to issue a non-medical life insurance policy. This means

the insurer waives the right to have the applicant physically or medically

examined.

Where the insurer agrees to issue a non-medical insurance policy, would that

constitute a waiver of the right to communication? No. What is waived is

only the right to have the applicant examined. And according to the Supreme Court,

where the insurer issues a non-medical life insurance policy, with more reason should

there be no concealment, no misrepresentation, on the part

of the applicant. Why? Because you can assume that the insurer, in agreeing

- 21 -

- 22 -

22

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

to issue the non-medical life insurance policy, he must have relied

entirely, completely, on the statements of the insured.

So, a non-medical insurance policy was issued because from his appearance, he

did not appear to be suffering from a serious ailment. He did not tell the

insurer that he was ill, he concealed that fact. Later, he died in a vehicular

accident.

Can the insurer rescind the contract on the ground of concealment? Yes. The fact

of illness was immaterial. Had he told the insurer that he was seriously ill, the

insurer would not have agreed to issue the policy. Such fact, if disclosed, would have

influenced the insurer in deciding whether or

not to issue the policy.

Assuming that the insurer would have, just the same, agreed to issue

the policy, the rate of premium would have been very high.

Of course, there are matters, which need not be communicated. Matters, which,

through the ordinary exercise of diligence could have been ascertained

by the insurer. This is similar to what we call in civil procedure as "judicial

notice," where the law presumes that a certain matter is known to both parties. Like

mercantile usages, practice, etc., these need not be communicated.

Or, where there is waiver, which may either be express or implied - waiver

of the right to communication. There is an express waiver when it is so stated in

the policy. There is an implied waiver when there is a neglect or

failure to inquire from facts which are communicated where they are distinctly

impaired. (Sec. 33)

ILLUSTRATION:

We must distinguish between an answer to a question which is manifestly

incomplete, yet accepted by the insurer, and an answer to a question which is

apparently complete but in fact incomplete and therefore, untrue. In the latter case,

there would be no waiver.

EXAMPLES:

i.

One of the questions asked of the applicant in an applicant for life

insurance is, "Have you ever been to a hospital?" Yes. The insurer

did not ask further questions, did not pursue the question. But the

applicant had been operated on twenty times.

Failure of the insurer to make further inquiries after the answer yes was

given is deemed to be a waiver of the right to communication.

The answer yes, means that there was something wrong with the health

of the applicant. A prudent insurer would have asked further, when?

Why? How many times? Etc.

Failure to do that on the part of the insurer would constitute a waiver of

the right to communication.

ii.

In the same example, the applicant is asked the following questions,

(1) Have you ever been confined in a hospital? Yes. (2) How many times? Two

times. (3) Why? I suffered from minor ailments like flu.

- 22 -

- 23 -

23

REVI EWER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

It turned out, however, that the applicant had been confined in a hospital

many times, and had gone major operations for some serious ailments.

Does this constitute a waiver? No, because in the second example, there are

answers which are apparently complete but which are in fact incomplete.

Therefore, the insurer may still rescind the contract by reason of

concealment.

MISREPRESENTATION

Like concealment, misrepresentation is a sin of commission. What is the purpose of

misrepresentation? Why would a party to a contract make misrepresentations to the

insurer? To induce the insurer to enter into a contract. That being the purpose,

misrepresentation is made either before or

at the time of the effectivity of the issuance of policy.

Normally, misrepresentations are not made after the issuance of the

policy, because they will not serve any purpose anymore.

After having convinced the insurer to enter into a contract, to issue the

policy, there is no point in making further misrepresentation. These are

made before.

However, there is an EXCEPTION where a representation is made even

after the effectivity of the insurance policy.

Sec. 47. The provisions of this chapter apply as well to a modification

of a contract of insurance as to its original formation.

EXAMPLE:

You insured your house. At the time of insuring it, you represented to the

insurer that it was being used for industrial purposes. And it was true.

Necessarily, between a building used exclusively for residential purposes

and one used for commercial or industrial purposes, the latter would command a

higher rate or premium, because the risk is greater.

Six months after the effectivity of the policy, a change in the nature of

the occupancy took place. You went bankrupt so you closed the business. There was

a change in the nature of the occupancy from commercia l or industrial to

residential. So you returned to the insurer and represented

to him that from this day on, the property would be used exclusively

for residential purposes and not as previously stated.

So here is a representation made after the effectivity of the insurance policy.

The purpose of which is to ask for the modification of the policy, in

order that the insurer may agree to a reduction of the premium. This is the

exception.

PROBLEM:

- 23 -

- 24 -

24

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

An applicant for a life insurance is asked the question, "Have you ever suffered

from any of the following diseases?" One of them is pneumonia. Answer: No. It was

untrue because at that time, he had suffered pneumonia.

There was no misrepresentation. However, while the policy was being

processed, he did suffer form pneumonia. But because of modern drugs, he

got cured before the issuance of the policy. So at that time of the issuance of

the policy, he was no longer suffering form pneumonia. But he

did suffer from pneumonia between the time of filing of the application and the

date of the effectivity of the policy. So he did not tell the insurer anymore that

he did suffer from pneumonia.

Then he died of cancer. Could the insurer deny the claim on the ground that there

was either concealment or misrepresentation? Yes.

RULE:

Statement in the case of representation must be true when the contract goes into

effect, although it may not be true when made.

On the other hand, even if true when made, but no longer true when the contract

goes into effect, that will give the insurer the right to rescind the contract.

Rescission is the remedy when there is concealment, misrepresentation,

and breach of warranty.

What are the limitations of the right of the insurer to rescind the contract

of insurance?

(1) Sec. 45. If a representation is false in a material point, whether

affirmative or promissory, the injured party is entitled to rescind the

contract from the time when the representation becomes false. The right to rescind

granted by this Code to the insurer is waived by the acceptance of premium payments

despite knowledge of the ground for rescission. (As amended

by Batasang Pambansa Blg. 874).

Simply, the second part of the foregoing provisions means: If the insurer

accepts premium payments despite knowledge of the ground for rescission, such

acceptance will constitute a waiver of the right to rescind.

EXAMPLE:

The insurer knew that there was misrepresentation. So, he could have asked for

the rescission of the policy. But instead of asking for the rescission of the

policy, he accepted the premium payments from the insured. Such acceptance

constitutes a waiver of the right to rescind.

What could be the purpose or reason of the insurer in accepting premium

payments instead of rescinding the policy, knowing that it could be

rescinded?

He expected that there would be no loss, there would be no claim, during the

term of the policy.

- 24 -

- 25 -

25

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Sec. 48. Whenever a right to rescind a contract of insurance is given to

the insurer by any provision of this chapter, such right must be

exercised previous to the commencement of an action on the contract.

After a policy of life insurance made payable on the death of the insured

shall have been in force during the lifetime of the insured for a

period of two years from the date of its issue or of its last

reinstatement, the insurer cannot prove that the policy is void ab initio

or is rescindible by reason of the fraudulent concealment or

misrepresentation of the insured or his agent.

(2) In a non-life policy, such right must be exercised prior to the

commencement of an action on the contract.

"Commencement of an action on the contract" - either in court or

with the Insurance Commissioner.

(3) In a life policy, defenses are available only during the first two years of

the insurance policy.

The period of two years for contesting a life policy by the insurer may be

shortened but it cannot be extended by stipulation.

If an insurer believes that the contract may be rescinded, he must do. He

must act before the insured files an action against the insurer for the recovery of

a claim. The second part is what is known as the incontestability clause.

WHAT IS THE INCONTESTABILITY CLAUSE?

A Clause stipulating that the policy shall be incontestable after a started period

; after the requisites are shown to exists, the insured shall be estopped from

contesting the policy or setting any defense, except as allowed, on the ground of

public policy.

REQUISITES OF INCONTESTABILITY CLAUSE?

1. Life insurance policy payable upon the death of the insured; and

2. Policy must have been in force for a period of at least two years during the

lifetime of the insured either from date of issue or date of

last reinstatement.

If the foregoing requisites concur, the insurer can no longer ask for the

rescission

of

the

contract

on

the

ground

of

concealment

or

misrepresentation. The policy has become incontestable.

But even if the policy of life insurance has become incontestable under Sec. 48

(2), the insurer can still raise certain defenses to defeat recovery,

like non-payment of the premiums. It does not mean that simply because a policy has

become incontestable, the insured need not pay the premiums anymore. Of course not.

- 25 -

- 26 -

26

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

Going back

to the insurer

In the case of

that he is the

interest)?

to concealment, is it necessary for the insurer to communicate

the nature and amount of his interest in the property insured?

a house, is the insured required to communicate to the insurer

owner (nature of interest) and that his house is worth P1M (amount of

As a rule, NO. If he is the absolute owner, he does not have to inform

the insurer of the nature and amount of his interest.

If, however, he is not the absolute owner, like in the case of a mortgagee,

under Sec. 8, then YES, he has to inform the insurer not only the nature of

his interest, the fact that he is a mortgagee, but he must also inform the insurer the

extent of his interest in the property, say P2M.

If the insured is the absolute owner, it is easy to ascertain the

extent of his interest, it is the value of the property.

If the insured is not the absolute owner, like a mortgagee, then his interest may

be less than the value of the property. It could only be the amount of the obligation

secured by the mortgage.

WHAT IS THE EFFECT WHEN THE POLICY BECOMES INCONTESTABLE?

The insurer cannot set up the defenses that:

a. The policy is void ab intitio;

b. It is rescissible by reason of fraudulent concealment of the insured

or his agent, no matter how patent or well-founded;

c. It is rescissible by reason of fraudulent misrepresentation of the

insured or his agent.

IS THE INCONTESTABLE CLAUSE ABSOLUTE?

No. It only deprives the insurer of those defenses which arise in

connection with the formation and operation of the policy prior to the loss.

The following defenses are still available:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

That the person taking the insurance lacked insurable interest

required by law.

That the cause of death of the insured is an excepted risk.

That the premiums have not been paid.

That the conditions of the policy relating to military or naval science

have been violated.

That the fraud is of a particular vicious type.

That the beneficiary failed to furnish proof of death or to comply with

any condition imposed by the policy after the loss had happened.

That the action was not brought within the time specified.

PURPOSE OF THE LAW:

The assure that after the specified period, the policy owner may rely

upon the insurance company to carry out the terms of the contract, regardless

of irregularities in connection with the application which may later be

discovered.

- 26 -

- 27 -

27

REVI EW ER IN INSURANCE LAW

As lectured by Dean Jose R. Sundiang

WHAT IS A POLICY?

It is the written instrument in which a contract of insurance is set

forth. (Sec. 49)

IS IT THE SAME AS THE INSURANCE CONTRACT ITSELF?

No.

CAN THERE BE A CONTRACT OF INSURANCE WITHOUT A POLICY?

As a rule, YES, because a policy is only an evidence of the contract.

HOW IS CONTRACT OF INSURANCE PERFECTED?

Being a consensual contract, as distinguished from a real contract, it is

perfected by mere consent. Concurrence between an offer and acceptance (in a

real contract, delivery is necessary for the perfection of the contract, like

the contract of pledge, loan, commodatum).

In a contract of insurance, the moment the parties agree or their minds meet, when

there is concurrence between the offer and acceptance, there is a

contract of insurance. A meeting of the minds on the object of the contract.

What may be the object? In life insurance, it is the life or health of a

person; in property insurance, like fire or marine, it is the property; in liability

insurance, it is the possible liability of a person by reason of the use of the

property. An example of liability insurance is what we call under Chapter VI as the

Compulsory Motor Vehicle Liability Insurance. The insurer under a liability type of

insurance is liable only with respect to the civil aspect. Criminal liability cannot

be insured because it is

something personal.

In Criminal Law, every person who is criminally liable is also civilly liable

(Art. 100, RPC). For example, one is involved in a vehicular accident

and he is at fault. He can be charged under Art. 365 of the RPC. But he can

also he held civilly liable for the damage to property that he have caused,

or the injury that another person may have sustained by reason of the accident. The

insurer will answer only for the civil liability, not for the criminal liability.

Sometimes after the issuance of the policy, the parties to the contract may find it

necessary to make certain alterations, modifications or changes or erasures. This can be

done without canceling the policy, which may prove to be not only expensive but also

tenious. How? It can be done through the use of riders, endorsements, warranties, and

clauses.