Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Status of South West Africa

Uploaded by

Mitchi JerezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Status of South West Africa

Uploaded by

Mitchi JerezCopyright:

Available Formats

Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders of the International Court of Justice

Not an official document

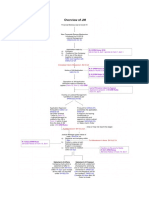

INTERNATFONAL STATUS OF SOUTH-WEST AFRICA

Adlvisory Opinion of 11 July 1950

The question concerning the International States of South

West Africa had been referred for an advisory opinion to the

Court by the General Assembly of the Unitecl Nations (G.A.

resolution of 6 December 1949).

The Court decided unanimously that South-West Africa

was a territory under the international Mandate assumed by

the Union of South Africa on December 17th. 1920;

by 12 votes to 2 that the Union of South Africa continued

to have the international obligations resulting,from the Mandate, including the obligation to submit reports and transmit

petitions from the inhabitants of that Territory, the supervisory functions to be exercised by the United Nations and the

reference to the Permanent Court of International Justice to

be replaced by reference to the International Court of Justice,

in accordance with Article 7 of the Mandate and Article 37 of

the Statute of the Court;

unanimously that the provisions of Chapter XI1 of the

Charter were applicable to the Territory of South-West

Africa in the,sense that they provided a means by which the

Territory may be brought under the 'lfusteeshiip system;

by 8 votes to 6 that the Charter did not impose on the Union

of South Africa a legal obligation to place the Territory under

Trusteeship;

and finally, unanimously that the Union of South Africa

was not competent to modify the international status of

South-West Africa, such competence resting 'with the Union

acting with the consent of the United Nations.

The circumstances in which the Court was called upon to

give its opinion were the following:

The Territory of South-WestAfrica was one of the German

overseas possessions in respect of which Gennany, by Article 119 of the Waty of Versailles renouncecl all her rights

and titles in favour of the Rincipal Allied and Associated

Pbwers. After the war of 1914-1918this Territory was placed

under a Mandate conferred upon the Union o:f South Africa

which was to have full power of administration and legislation over the Temtory as an integral portion of the Union.

The Union Government was to exercise an! international

function of administration on behalf of the League, with the

object of promoting the well-being and development of the

inhabitants.

After the second world war, the Union of South Africa,

alleging that the Mandate had lapsed, sought tlne recognition

of the United Nations to the integration of the Territory in the

Union.

The United Nations refused their consent to this integration andinvited the LJnion of South Africa to place the Territory under 'ltusteeship, according to the provisions of Chapter XI1 of the Charter.

The Union of South Africa having refused to comply, the

General Assembly of the United Nations, on December 6th.

1949, adopted the following resolution:

The General Assembly,

Recalling its previous resolutions 65 (I) of 14 December

1946, 141 (11) of 1 November 1947 and 227 (111) of 26

November 1948 corrcerning the Territory of South-West

Africa,

Considering that it is desirable that the General Assembly.

for its further consideration of the question, should obtain an

advisory opinion on its legal aspects,

1. Decides to submit the following questions to the International Court of Justice with a request for an advisory opinion which shall be transmitted to the General Assembly

before its fifth regular session, if possible:

"What is the international status of the Territory of

South-West Africa and what are the international obligations of the Union of South Africa arising therefrom, in

particular:

"(a) Does the Union of South Africa continue to have

international obligations under the Mandate for SouthWest Africa and, if so, what are those obligations?

"(b) Are the pmvisions of Chapter XI1 of the Charter

applicable and, if so, in what manner, to the Territory of

South-West Africa?

"(c) Has the Union of South Africa the competence to

modify the internat.iona1 status of the Territory of SouthWest Africa, or, in the event of a negative reply, where

does competencerest to determine and modify the international status of the Territory?"

2. Requests the Secretary-General to transmit the

present resolution to the International Court of Justice, in

accordance with Article 65 of the Statute of the Court,

accompanied by all dccuments likely to throw light upon the

question.

The Secretary-General shall include among these documents the text of articlle 22 of the Covenant of the League of

Nations; the text of the Mandate for German South-West

Africa, confirmed by the Council of the League on 17

December 1920; relelvant documentation concerning the

objectives and the functions of the Mandates System; the text

of the resolution adopted by the League of Nations on the

Continued on next page

question of Mandates on 18 April 1946; the: text of Articles

77 and 80 of the Charter and data on the discussion of these

Articles in the San Francisco Conference ;and the General

Assembly; the report of the ]Fourth Commit.teeand the officia1 records, including the alnnexes, of the ,consideration of

the question of South-West A.fricaat the foui-th session of the

General Assembly.

tories not placed under the new trusteeship system were

neither expressly transferred to the United Nations, nor

expressly assumed by that Organization. Nevertheless, the

obligation incumbent upon a Mandatory State to accept international supervision and to submit reports is an important

part of the Mandates System. It could not be concluded that

the obligation to submit to supervision had disappeared

merely because the supervisory organ had ceased to exist,

when the United Nations had another international organ

performing similar, though not identical, supervisory functions.

These general considerations were confirmed by Article

80, paragraph 1, of the Charter, which purports to safeguard

not only the rights of States, but also the rights of the peoples

of mandated territories until trusteeship agreements were

concluded. The competence of the General Assembly of the

United Nations to exercise such supervision and to receive

and examine reports is derived from the provisions of Article

10 of the Charter, which authorizes the General Assembly to

discuss any questions on any matters within the scope of the

Charter, and make recommendations to the Members of the

United Nations. Moreover, the Resolution of April 18th.

1946, of the Assembly of the League of Nations presupposes that the supervisory functions exercised by the

League would be taken over by the United Nations.

The right of petition was not mentioned in the Covenant

0, the Mandate, but was organized by a decision of the Council of the League. The Court was of opinion that this right

which the inhabitants of South-West Africa had thus

acquin:d, was maintained by Article 80, paragraph 1, of the

Charter, as this clause was interpreted above. The Court

was therefore of the opinion that petitions ale to be transmitted by the Government of the Union to the General Assembly

of the IJnited Nations, which is legally qualified to deal with

them.

Therefore, South-West Africa is still to be considered a

territory held under the Mandate of December 17th. 1920.

The degree of supervision by the General Assembly should

not exceed that which applied under the Mandates System.

These observations apply to annual reports and petitions.

Having regard to Article 37 of the Statute of the Internstional ~Counof Justice and Article 80, paragraph 1, of the

Charter, the Court was of opinion that this clause in the Mandate was still in force, and therefore that the Union of South

Africa was under an obligation to accept the compulsory

jurisdiction of the Court according to those provisions.

wimregard to question (b)the Court said that Chapter

of the Charter applied to the Territory of South-West Africa

in this sense, that it provides a means by which the Territory

may be brought under the trusucship system.

With regard to the second part of the question, dealing

with the manner in which those provisions ae applicable, the

Court said that the pmvisions of this chapter did not impose

upon the Union of SouthAfricaan obligationto put theTerrimsteeship by means of a msteeship Agrretory

Inis opinion is bsaed on the pnmisaive language of

Articles75 and 77. These Articles refer to an uagcwnent,,

which implies consent of the parties

The fact that

Article 77 refers to the "voluntarywplacement of certain Territories under Tmsteeship does not show that the placing of

other krritories under

is compulsory. The word

6.voluntaryM used with respct to territories in caDgory

in Article 77 can be explained as having been used out

of an abundance of caution and as an added assurance of free

initiative to States having territories falling within that crategory.

In its opinion the Court examined first if the Mandate conferred by the Principal Allie~cland Associated Powers on His

Britannic Majesty, to be exeicised on his beh~alfby the Union

of South Africa, over the Tenritory of South-West Africa was

still in existence. The Court declared that the: League was not

a "mandator" in the sense in which this term is used in the

national law of certain states. The Mandate had only the

name in common with the several notion!; of mandate in

national law. The essentially international character of the

functions of the Union appeared from the: fact that these

functions were subject to the supervision of the Council of

the League and to the ob1iga~:ionto present t~nnusllreports to

it; it also appeared from tht: fact that any Member of the

League could submit to the Fbrmanent C O Uof

~ :International

Justice any dispute with the: Union Government relating to

the interpretation Or the application of the frovisions of the

Mandate.

The international obligations assumed by the Union of

South Africa were of two kinds. One kind was directly

related to the administration of the Territory and cornsponded to the sacred trust of civilization reft:rnd to in article

22 of the Covenant; the o&s:r related to the machinery for

implementation and was c1,osely linked to the supervision

and control of the League. It corresponded to the "securities

for the performance of this trust" referred, to in the Same

Article.

The obligations of the lint goup represent the very

essence of the sacred trust of'civilization. Thieir rczison d'etre

and original object remain. Since their fulfilment did not

depend on the existence of the League of Naltions, they could

not be brought to an end n~.erelybecause this supervisory

organ ceased to exist. This view is confirme:dby Article 80,

paragraph 1, of the Charter, mainmining tht: rights of States

and peoples and the terms Of existing international instruments until the territories in question are placed under the

trusteeship system. MOreova!r,the resolutioe of the League

of Nations of April 18, 1946, said that the League's functions with respect to mandated territories would come to an

end; it did not say that the Mandates thennselves came to

an end.

By this Resolution the Assembly of the League: of Nations

manifested its understandin;p: that the Mandates would continue in existence until "otlier rmangemen!ts" were established and the Union of South Africa, in declarationsmade to

the League of Nations as well as to the United Nations, had

recognized that its ob1igatio:asunder the Mandate continued

of the League' Interpretationplaced

the

upon legal insmunents Iihe pmies them, though

conclusive as to their meaning, have considerable probative

value when they contain remgnition by a party of its own

obligations under an instru~r~~ent.

With regard to the second.group of obligsitions, the Court

said that some doubts might arise from the fact that the supervisory functions of the Leaglue with regard to mandated terri13

The Court considered that if Article 80, paragraph 2 had

been intended to create an obligation for a M[andatory State to

negotiate and conclude an agreement, such intention would

have been expressed in a direct manner. It considered also

that this article did not create an obligation tlo enter into negotiations with a view to concluding a Trusteeship Agreement

as this provision expressly refers to delay or postponement

"of the negotiation and conclusion", and not to negotiations

only. Moreover, it refers not merely to temtories held under

mandate but also to other temtories. Finally the obligation

merely to negotiate does not of itself assure the conclusion of

Trusteeship Agreements. It is true that the Charter has contemplated and regulated only one single system, the international Trusteeship system. If it may be conc:luded that it was

expected that the mandatory States would follow the normal

course indicated by the Charter and conclude Trusteeship

Agreements, the Court was unable to deduct: from these general considerationsany legal obligation for inandatory States

to conclude or negotiate such agreements. It is not for the

Court to pronounce on the political or moral duties which

these considerationsmay involve.

With regard to question (c) the Court idecided that the

Union had no competence to modify unilaterally the international status of the Territory. It repeated that: the normal way

of modifying the international status of the Territory would

be to place it under the Trusteeship System by means of a

Trusteeship Agreement, in accordance with ,theprovisions of

Chapter XI1 of the Charter.

Article 7 of the Mandate required the authorisation of the

Council of the League for any modifications of its terms. In

accordance with the reply given to question (a) the Court said

that those powers of supervision now belong to the General

Assembly of the United Nations. Articles 79 and 85 of the

Charter required that a trusteeship agreement be approved by

the General Assembly. By analogy it could be inferred that

the same procedure was applicable to any modification of the

internationalstatus of a temtory under Mandate which would

not have for its purpose the placing of the territory under the

trusteeship system.

Moreover, the Union of South Africa itself decided to submit the question of .the future international status of the territory to the "judgment" of the General Assembly as the

"competent international organ". In so doing, the Union

recognised the collilpetence of the General Assembly in the

matter. On the bash of these considerations, the Court concluded that compete:nce to determine and modify the international status of the Territory rested with the Union, acting in

agreement with the United Nations.

Sir Arnold McFJair and Judge Read appended to the

Court's Opinion a statement of their separate opinions.

Availing themselves of the right conferred on them by

Article 57 of the Statute, Judges Alvarez, De Visscher and

Krylov appended tal the Opinion statements of their dissenting opinions.

Vice-President Guerrero declared that he could not concur

in the Court's opinion on the answer to question (b).For him,

the Charter imposed on the South African Union an obligation to place the Territory under Trusteeship. On this point

and on the text in general, he shared the views expressed by

Judge De Visscher.

Judges Zoricic and Badawi Pasha declared that they were

unable to concur in the answer given by the Court to the second part of the question under letter (b)and declared that they

shared in the general1views expressed on this point in the dissenting opinion of Judge De Visscher.

The Court's opinion was given in a public hearing. Oral

statements were presented on behalf of the SecretaryGeneral of the United Nations by the Assistant SecretaryGeneral in charge of'the Legal Department, and on behalf of

the Governments of the Philippines and of the Union of

South Africa.

You might also like

- Air Philippine Corp V Pennswell IncDocument1 pageAir Philippine Corp V Pennswell IncPablo Jan Marc FilioNo ratings yet

- Evidence Project Volume2Document85 pagesEvidence Project Volume2Reah CrezzNo ratings yet

- GR No. 163338 Luzon DB V Conquilla Et AlDocument9 pagesGR No. 163338 Luzon DB V Conquilla Et AlMichelle de los Santos100% (1)

- Presidential Decree No. 1067 Water Code of The Philippines BackgroundDocument23 pagesPresidential Decree No. 1067 Water Code of The Philippines BackgroundJoanne besoy100% (1)

- Philtranco Vs ParasDocument9 pagesPhiltranco Vs ParasChingkay Valente - JimenezNo ratings yet

- Robinson & Co. v. Belt, 187 U.S. 41 (1902)Document8 pagesRobinson & Co. v. Belt, 187 U.S. 41 (1902)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PHIvCHINA PDFDocument26 pagesPHIvCHINA PDFJamie VodNo ratings yet

- Prosecution First Charge Against ColonelDocument4 pagesProsecution First Charge Against ColonelJesse RazonNo ratings yet

- Villa Rey Transit V Ferrer DigestDocument1 pageVilla Rey Transit V Ferrer DigestJoni AquinoNo ratings yet

- Payment Undertaking TitleDocument1 pagePayment Undertaking Titleanon_762670605No ratings yet

- CORFU CHANNEL INCIDENT (UK v ALBANIA) (1948, 1949Document2 pagesCORFU CHANNEL INCIDENT (UK v ALBANIA) (1948, 1949Francis MasiglatNo ratings yet

- Claro M. Recto For Petitioners. Ramon Diokno and Jose W. Diokno For RespondentsDocument4 pagesClaro M. Recto For Petitioners. Ramon Diokno and Jose W. Diokno For Respondentsnia_artemis3414No ratings yet

- COA negligence ruling upheld for P12.5K robbery lossDocument45 pagesCOA negligence ruling upheld for P12.5K robbery lossMary Therese Gabrielle EstiokoNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Dev. Authority v. Dolefil Agrarian Reform Bene Ciaries - DIGESTDocument3 pagesCooperative Dev. Authority v. Dolefil Agrarian Reform Bene Ciaries - DIGESTAngelica AbonNo ratings yet

- Citibank Vs Hon ChuaDocument12 pagesCitibank Vs Hon ChuaJA BedrioNo ratings yet

- Albania responsible for Corfu Channel minesDocument2 pagesAlbania responsible for Corfu Channel minesHemanth RaoNo ratings yet

- RTC Erred in Dismissing Intra-Corp CaseDocument1 pageRTC Erred in Dismissing Intra-Corp CaseStef Turiano PeraltaNo ratings yet

- March 4 DigestsDocument16 pagesMarch 4 DigestsRem SerranoNo ratings yet

- Corpo Cases CompiledDocument20 pagesCorpo Cases CompiledJacqueline Carlotta SydiongcoNo ratings yet

- Alrai v. Maramion DigestDocument3 pagesAlrai v. Maramion DigestTrisha Paola TanganNo ratings yet

- Constantino V. Cuisia and Del Rosario PDFDocument43 pagesConstantino V. Cuisia and Del Rosario PDFNatsu DragneelNo ratings yet

- Andamo V IECDocument8 pagesAndamo V IECMarkKevinAtendidoVidar100% (1)

- 21 103Document29 pages21 103Pen ValkyrieNo ratings yet

- PIL J DigestsDocument17 pagesPIL J DigestsJoem MendozaNo ratings yet

- GILAT Satellite Vs UCPBDocument8 pagesGILAT Satellite Vs UCPBGloria Diana Dulnuan0% (1)

- ES5600-ES5607 Coursework TaskDocument8 pagesES5600-ES5607 Coursework Taskikvinder randhawaNo ratings yet

- Complete Cases For Finals CORPODocument78 pagesComplete Cases For Finals CORPODaryll Phoebe EbreoNo ratings yet

- Ang v. AngDocument9 pagesAng v. AngAhmedLucmanSangcopanNo ratings yet

- Case Digest G R No 160932 January 14 2013Document3 pagesCase Digest G R No 160932 January 14 2013Nathaniel Niño TangNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Trial Court Erred in Awarding Custody Based on Assumptions About Law School DemandsDocument2 pagesSupreme Court Rules Trial Court Erred in Awarding Custody Based on Assumptions About Law School DemandsBettina Rayos del SolNo ratings yet

- Soccorro Clemente vs. RPDocument7 pagesSoccorro Clemente vs. RPJazztine ArtizuelaNo ratings yet

- Case Digests of 13 14Document2 pagesCase Digests of 13 14Anonymous sgEtt4No ratings yet

- Bandillon V LFUC - CorpinDocument3 pagesBandillon V LFUC - CorpinAndrew GallardoNo ratings yet

- Tai Tong Chuache & Co. V. The Insurance Commission and Travellers Multi-IndemnityDocument8 pagesTai Tong Chuache & Co. V. The Insurance Commission and Travellers Multi-IndemnityRodeleine Grace C. MarinasNo ratings yet

- Corp, Set 2, DigestDocument18 pagesCorp, Set 2, DigestApureelRoseNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank Vs CADocument6 pagesPhilippine National Bank Vs CAHamitaf LatipNo ratings yet

- 006 COSCOLLUELA Re in The Matter of Clarification of ExemptionDocument2 pages006 COSCOLLUELA Re in The Matter of Clarification of ExemptionKatrina CoscolluelaNo ratings yet

- CIVIL LIABILITY ARISING FROM CRIMEDocument2 pagesCIVIL LIABILITY ARISING FROM CRIMEAbigael SeverinoNo ratings yet

- Asset Privatization Trust V CADocument1 pageAsset Privatization Trust V CAEugene Albert Olarte JavillonarNo ratings yet

- Metropolitank Bank & Trust Company vs. Court of Appeals, Golden Savings & Loan Association Inc., Lucia Castillo & Gloria CastilloDocument2 pagesMetropolitank Bank & Trust Company vs. Court of Appeals, Golden Savings & Loan Association Inc., Lucia Castillo & Gloria CastilloTrudgeOnNo ratings yet

- Korea Exchange Bank V Filkor Business Integrated, Inc G.R. No 138292Document5 pagesKorea Exchange Bank V Filkor Business Integrated, Inc G.R. No 138292Ruel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Pale Reviewer PDFDocument51 pagesPale Reviewer PDFNinoNo ratings yet

- UEM MARA PHILIPPINES CORPORATION v. ALEJANDRO NG WEEDocument1 pageUEM MARA PHILIPPINES CORPORATION v. ALEJANDRO NG WEErolandodjrelucioNo ratings yet

- Chattel MortageDocument11 pagesChattel MortageAmie Jane MirandaNo ratings yet

- Revalida - 4. Cha Vs CADocument2 pagesRevalida - 4. Cha Vs CADonna Joyce de BelenNo ratings yet

- Abad Santos, Camu and Delgado, For Appellant. J.W. Ferrier For AppelleesDocument6 pagesAbad Santos, Camu and Delgado, For Appellant. J.W. Ferrier For AppelleesChristine Rose Bonilla LikiganNo ratings yet

- Ben Line's appeal dismissalDocument26 pagesBen Line's appeal dismissalIshNo ratings yet

- Pada Kilario vs. Ca PDFDocument14 pagesPada Kilario vs. Ca PDFCJ CasedaNo ratings yet

- Sandoval - V - Caneba - G.R. No. 90503 PDFDocument3 pagesSandoval - V - Caneba - G.R. No. 90503 PDFEffy SantosNo ratings yet

- SMC vs. KhanDocument19 pagesSMC vs. KhanGuiller MagsumbolNo ratings yet

- Court Holds Telecom Firm Liable for Libelous TelegramDocument3 pagesCourt Holds Telecom Firm Liable for Libelous TelegramRon ManNo ratings yet

- CASE No. 51 Agbada vs. Inter-Urban DevelopersDocument2 pagesCASE No. 51 Agbada vs. Inter-Urban DevelopersAl Jay Mejos100% (1)

- Vigilance Over GoodsDocument117 pagesVigilance Over GoodsCol. McCoyNo ratings yet

- Lopez vs. Orosa, JR., and Plaza Theatre, Inc PDFDocument9 pagesLopez vs. Orosa, JR., and Plaza Theatre, Inc PDFresjudicataNo ratings yet

- US Naval Base Contracts Upheld as Governmental FunctionsDocument2 pagesUS Naval Base Contracts Upheld as Governmental FunctionsJustineMaeMadroñal100% (1)

- OPOSA V FACTORAN ESTABLISHES INTERGENERATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY AND LEGAL STANDING FOR FUTURE GENERATIONSDocument42 pagesOPOSA V FACTORAN ESTABLISHES INTERGENERATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY AND LEGAL STANDING FOR FUTURE GENERATIONSEnrique Paolo MendozaNo ratings yet

- PDF International Status of South West Africa PDFDocument3 pagesPDF International Status of South West Africa PDFLuigiMangayaNo ratings yet

- 49 Intl Status SW AfricaDocument2 pages49 Intl Status SW AfricaClaire PascuaNo ratings yet

- Reports & Petitions Concerning South-West Africa CaseDocument3 pagesReports & Petitions Concerning South-West Africa CaseMalcom GumboNo ratings yet

- Higgins - 1966 - The International Court and South West AfricaDocument28 pagesHiggins - 1966 - The International Court and South West AfricaLast ColonyNo ratings yet

- DissolutionDocument7 pagesDissolutionAnet GetNo ratings yet

- 1st Batch Case Digest TortsDocument17 pages1st Batch Case Digest TortsMitchi JerezNo ratings yet

- General Insurance and Surety Corporation vs. Republic of the PhilippinesDocument2 pagesGeneral Insurance and Surety Corporation vs. Republic of the PhilippinesMitchi JerezNo ratings yet

- Towers Assurance liability on counterbond for Ororama Supermart caseDocument1 pageTowers Assurance liability on counterbond for Ororama Supermart caseMitchi Jerez0% (1)

- Province of North Cotabato V Government of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesProvince of North Cotabato V Government of The Republic of The PhilippinesStef Macapagal91% (11)

- Eichmann Trial Upholds Nazi ProsecutionDocument2 pagesEichmann Trial Upholds Nazi ProsecutionMitchi JerezNo ratings yet

- The Paquete HabanaDocument24 pagesThe Paquete HabanajafernandNo ratings yet

- Western SaharaDocument5 pagesWestern SaharaJurico AlonzoNo ratings yet

- PartnershipDocument72 pagesPartnershipMitchi JerezNo ratings yet

- Poe-Llamanzares v. COMELEC GR. No. 221697Document47 pagesPoe-Llamanzares v. COMELEC GR. No. 221697lenard5No ratings yet

- Partnership Cases 1-17Document63 pagesPartnership Cases 1-17Mitchi JerezNo ratings yet

- Basic Technical WritingDocument395 pagesBasic Technical WritingMitchi Jerez100% (1)

- List of Cases (State Immunity)Document42 pagesList of Cases (State Immunity)Mitchi JerezNo ratings yet

- Legal Counselling MIDTERMSDocument3 pagesLegal Counselling MIDTERMSAldrin John Joseph De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 3:13-cv-05038 #29Document138 pages3:13-cv-05038 #29Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Quilban Vs RobinulDocument6 pagesQuilban Vs RobinulKatrina BudlongNo ratings yet

- MES Fees Regulation Rules 2016Document22 pagesMES Fees Regulation Rules 2016Hemant Sudhir WavhalNo ratings yet

- Taxation Law 1 Report By: Ada Mae D. Abellera Olan Dave L. LachicaDocument3 pagesTaxation Law 1 Report By: Ada Mae D. Abellera Olan Dave L. Lachicadave_88opNo ratings yet

- IPL Case Digest - Joaquin V DrilonDocument5 pagesIPL Case Digest - Joaquin V Drilonmma100% (1)

- Quimpo v. Tanodbayan, 1986Document3 pagesQuimpo v. Tanodbayan, 1986Deborah Grace ApiladoNo ratings yet

- COMELEC ruling on election protest upheldDocument2 pagesCOMELEC ruling on election protest upheldNikki Estores Gonzales100% (6)

- Sps Luis Manuelita Ermitao Vs CA BPI Express CDocument5 pagesSps Luis Manuelita Ermitao Vs CA BPI Express CBella AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Filed in Forma Pauperis Court Stamped 962015 DocumentDocument26 pagesFiled in Forma Pauperis Court Stamped 962015 Documentleenav-1No ratings yet

- 19 Tuvillo V Judge LaronDocument16 pages19 Tuvillo V Judge LaronJonah BucoyNo ratings yet

- 7th Legislative Drafting Competition 2018 RULESDocument6 pages7th Legislative Drafting Competition 2018 RULESMohd ArifNo ratings yet

- Gokongwei VS SecDocument17 pagesGokongwei VS SecImariNo ratings yet

- 07 - DHL Philippines Corp. v. Buklod NG Manggagawa NG DHL Philippines Corp., - BacinaDocument2 pages07 - DHL Philippines Corp. v. Buklod NG Manggagawa NG DHL Philippines Corp., - BacinaChaNo ratings yet

- Forgie-Buccioni v. Hannaford Brothers, 413 F.3d 175, 1st Cir. (2005)Document9 pagesForgie-Buccioni v. Hannaford Brothers, 413 F.3d 175, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Merry Products v. Test Rite ProductsDocument7 pagesMerry Products v. Test Rite ProductsPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Social Work Scholars Representation of Rawls A Critique - BanerjeeDocument23 pagesSocial Work Scholars Representation of Rawls A Critique - BanerjeeKarla Salamero MalabananNo ratings yet

- Case of Dakir v. BelgiumDocument22 pagesCase of Dakir v. BelgiumAndreea ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Formal Statement PDFDocument1 pageFormal Statement PDFCarolinaNo ratings yet

- VakalatnamaDocument1 pageVakalatnamaAadil KhanNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesDocument14 pagesDoctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesEmmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciNo ratings yet

- Role of JudgesDocument21 pagesRole of Judgeschidige sai varnithaNo ratings yet

- Research Essay - RapeDocument3 pagesResearch Essay - RapeTrevor SoNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension. 4th GradersDocument25 pagesReading Comprehension. 4th GradersMARÍA JOSÉ GÓMEZ VERANo ratings yet

- Panaguiton Jr. vs. DOJDocument4 pagesPanaguiton Jr. vs. DOJAngel NavarrozaNo ratings yet

- Law EconomicsDocument2 pagesLaw EconomicsDhwanit RathoreNo ratings yet

- Elsenheimer Discrimination LawsuitDocument14 pagesElsenheimer Discrimination LawsuitNews 8 WROCNo ratings yet

- SC upholds conviction of Anita Miranda for illegal drug saleDocument1 pageSC upholds conviction of Anita Miranda for illegal drug saleJanMikhailPanerioNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Interest Disclosure Form - March 2018Document3 pagesConflict of Interest Disclosure Form - March 2018Vakati HemasaiNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Judicial Management in MalaysiaDocument17 pagesAn Overview of Judicial Management in MalaysiaTan Ji Xuen100% (1)