Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Simple Steps To Hasten Postoperative Recovery 2167 0420.1000137

Uploaded by

Ibnu SyahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Simple Steps To Hasten Postoperative Recovery 2167 0420.1000137

Uploaded by

Ibnu SyahCopyright:

Available Formats

Katz and Nelson, J Womens Health Care 2013, 2:4

http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2167-0420.1000137

Womens Health Care

Review Article

Open Access

Simple Steps to Hasten Post-Operative Recovery

Felicia Katz and Anita Nelson*

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Los Angeles BioMedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical CenterTorrance, CA, USA

Abstract

Early recovery from major surgery is desirable both from the perspective of patient satisfaction, as well as costeffectiveness. Prolonged hospital stays after surgery can result in increased morbidity, including deep vein thrombosis

and nosocomial infections such as pneumonia, and can rapidly increase hospital costs and reduce reimbursement.

Keywords: Post-operative recovery; Pneumonia; Nosocomial

infections

Introduction

Early recovery from major surgery is desirable both from the

perspective of patient satisfaction, as well as cost-effectiveness.

Prolonged hospital stays after surgery can result in increased

morbidity, including deep vein thrombosis and nosocomial infections

such as pneumonia, and can rapidly increase hospital costs and reduce

reimbursement [1]. All patients recovering from major surgery in

gynecology and obstetrics must meet several post-operative milestones

before being discharged from the hospital, including tolerating a diet,

being able to ambulate, passing flatus, voiding spontaneously, and

adequate pain control with oral pain medication. In order to help our

patients achieve these milestones, there are many aspects of traditional

post-operative management that must be questioned, and simple

evidence-based steps that can be taken to hasten short-term postoperative recovery.

Early post-operative feeding

Tradition has dictated that feeding after surgery not be initiated

until after the patient has passed flatus or has normal bowel sounds,

indicating a return to bowel function. The rationale for this practice

was that early feeding prior to return to bowel function was thought

to result in increased nausea and vomiting which would, in addition

to causing the patient discomfort, result in increased risk of aspiration

and necessity of nasogastric tube placement [1]. It was also thought that

early feeding would exacerbate normal post-operative ileus and result

in worsening abdominal distension and wound dehiscence. However,

more and more data has suggested that these presumed risks of early

feeding are unfounded, and that early feeding is both safe and effective

in reducing short-term post-operative recovery time for appropriate

patients.

In 1998, a randomized controlled trial was conducted by Pearl et

al. [1] in which 200 gynecological oncology patients undergoing intraabdominal surgery were randomized to either receive traditional postoperative management (i.e. nothing by mouth until passing of flatus) or

immediate initiation of clear liquid diet, to be advanced as tolerated [1].

While post-operative complications were found to be equal between

the two groups, it was found that the early feeding group experienced

significantly shorter hospital stays (how long??), and had shorter time

until onset of bowel sounds. Several years later, in 2002, the same

authors conducted a similar study of 254 gynecological oncology

patients [2], this time comparing early initiation of clear liquid diet

versus regular diet. All patients received a diet on the first post-operative

day unless they were experiencing significant vomiting or abdominal

distension. Patients were randomized to receive either clear liquid diet

or regular diet as their first post-operative meal. When post-operative

complications and length of hospital stay were compared, there were

found to be no differences between the two groups.

J Womens Health Care

ISSN: 2167-0420 JWHC, an open access journal

In 2007, a meta-analysis of randomized studies of early versus

traditional feeding after major abdominal gynecologic surgery was

performed and published in the Cochrane database [3]. The findings

were consistent with previous studies, indicating that early feeding

(within 24 hours of surgery regardless of bowel function) is associated

with shorter onset of bowel sounds, shorter time until first solid meal,

and average reduced length of hospital stay of 0.73 days. As with prior

studies, there were no differences in the rates of post-operative ileus,

abdominal distention, nasogastric tube placement, pneumonia, or

wound complications. They did not find a significant difference in the

time until onset of flatus, and patients in the early feeding group did

experience more nausea.

A similar Cochrane database meta-analysis was performed in

patients undergoing cesarean section in 2002 [4]. Six studies were

included, with patients having received both general and regional

anesthesia. As with gynecological surgery, there was found to be a

reduced onset to bowel sounds (average difference four hours), and

reduced length of hospital stay (average difference of 0.75 days), and

there were no differences in post-operative complications. As stated in

the conclusion, there is no evidence support withholding PO intake

from uncomplicated post-operative patients.

Previous tradition in post-operative management regarded

gastro-intestinal surgery as an especially important case in which to

delay enteral feeding. In terms of gynecology, dissection involving

bowel and repair of bowel injury has often been a justification for

withholding feeding until clinical evidence of return to bowel function,

and a contraindication to early feeding. However, the literature on GI

surgery has not shown any clear benefit to this practice. A Cochrane

database meta-analysis of 13 randomized trials involving 1173 patients

undergoing gastro-intestinal surgery was published in 2006 [5].

Although results were non-significant, the data seemed to indicate

that early enteral feeding, even in patients with bowel anastomosis,

was associated with reduced post-operative complications and

reduced length of hospital stay. There was no evidence supporting

the presumption that early feeding results in increased leakage of

anastomosis or other complications, although further data is needed.

*Corresponding author: Anita Nelson, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Los Angeles BioMedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Torrance, CA, USA, Tel: 310-222-2345; E-mail: anitalnelson@earthlink.net

Received July 19, 2013; Accepted November 18, 2013; Published November

24, 2013

Citation: Katz F, Nelson A (2013) Simple Steps to Hasten Post-Operative Recovery.

J Womens Health Care 2: 137. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000137

Copyright: 2013 Katz F, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and

source are credited.

Volume 2 Issue 4 1000137

Citation: Katz F, Nelson A (2013) Simple Steps to Hasten Post-Operative Recovery. J Womens Health Care 2: 137. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000137

Page 2 of 3

Gum chewing

Numerous studies have looked at the effect of so-called shamfeeding, in which neuronal pathways of oral intake are stimulated by

gum-chewing hasten the return of coordinated propulsive activity in

the intestines. A meta-analysis of multiple older studies in the general

surgical literature was performed [6], and showed that gum-chewing

reduced the time to flatus by 20 hours, and time to bowel movement

by 29 hours. There was also a non-significant trend toward reduced

hospital stay. Two recent randomized controlled trials focusing on

gynecologic patients have now further confirmed these findings.

The first was in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing open

hysterectomy and staging procedures, and showed that gum chewing

significantly reduced the time to flatus, time to bowel movement,

time to tolerate diet, and length of hospital stay. The second focused

on patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopy, and found that gum

chewing every 2 hours reduced the time to flatus and regular bowel

sounds postoperatively, with no adverse side effects.

Other methods of reducing post-operative ileus

Post operative ileus refers to the decreased GI motility associated

with surgery, especially open abdominal procedures. Normal postoperative ileus can be expected to last 1-3 days. The mechanisms

are multifactorial [7]. The main cause is thought to be disorganized

electrical activity within the GI smooth muscle, preventing coordinated

peristalsis [8,9]. In addition, excessive manipulation of the intestines

during surgery produces a sympathetic neural reflex that inhibits

GI motor neurons, decreases secretions, and increases sphincter

contraction [10]. The stress of surgery on the body also results in

increased pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines, which contribute

to reduced GI motility. Other iatrogenic practices contribute to the

problem as well: aggressive pre-operative mechanical bowel prep

and overuse of opioid analgesia compound the problem of decreased

GI motility [11]. It was previously thought that peri-operative fluid

overloading caused intestinal edema significant enough to prolong

post-operative ileus, although studies on peri-operative fluid restriction

have not demonstrated any improvement [12].

While some of these problems are an unavoidable consequence of

abdominal surgery, the clinician can take steps to reduce or prevent

other practices that contribute to prolonged ileus. These include:

Avoiding aggressive pre-operative mechanical bowel prep and

excessive pre-operative fasting if possible [7]

Use of NSAIDs such as ketorolac (Toradol) to reduce opioid

use [7]; use of PCA has been shown to slightly prolong postoperative ileus, but is not associated with increased length

of hospital stay, and provides improved analgesia without

increasing cumulative opioid dose [13]

Stimulant laxatives such as biscodyl (Dulcolax) in place of stool

softeners such as docusate (Colace) [7,14]

Early ambulation

In addition to psychologically preparing patients for discharge and

resuming their independence and daily activities, early ambulation

is one of the key steps in prevention of deep vein thrombosis. DVT

and pulmonary embolus remain among the most significant causes

of morbidity and mortality in post-operative patients, in spite of

well-known means of prophylaxis, including sequential compression

devices during periods of immobilization, chemoprophylaxis with

temporary anticoagulation, and early ambulation.

J Womens Health Care

ISSN: 2167-0420 JWHC, an open access journal

In order to successfully implement early ambulation in a safe

manner, the entire care team must be involved, especially in removing

barriers to early ambulation. Unless contraindicated, removal of

the foley catheter in the morning of post-operative day 1 will make

ambulating more comfortable and will incentivize ambulating to the

restroom. Although there is little data from gynecology regarding

optimal duration of bladder drainage, literature from colorectal surgery

indicates that removing the catheter on day 1 reduces incidence of

UTI and is not associated with higher rates of urinary retention [15].

Nursing must be involved in encouraging patients out of bed and

assisting patients during ambulation to prevent falls. Overuse of opioid

medication has been shown to delay ambulation by causing decreases in

arterial pressure that result in orthostatic intolerance [16]. Combining

NSAIDs with less potent opioids rather than relying solely on potent

opioids will improve a patients ability to ambulate on post-operative

day 1, and may prevent complications such as falls and syncope.

It has been suggested (and many practitioners believe) that

ambulation promotes early passing of flatus. However, a study of 34

patients did not show increased seromuscular activity in the GI tract

after early ambulation.

Patient education and pre-operative counseling

Patient expectations have been shown to influence post-operative

outcomes. Specifically, appropriate pre-operative counseling regarding

expected length of hospital stay and appropriate anticipation of pain

level post-operatively has actually been shown to improve overall

patient perception of pain [17]. Anxiety is associated with a slower

and more complicated post-operative course, as anxiety influences

behavioral, psychological, and even neuroimmunological function, and

exaggerates perception of pain. It is known that psychological stress

prolongs wound healing [18]. Thus, detailed pre-operative counseling

can play a role in alleviating patient anxiety, so that the patient knows

what to expect.

Fast track

One problem with many of the previously described methods of

improving post-operative recovery is that from a clinical standpoint,

the reductions in hospital stay and return to normal functioning is

modest at best. However, there has recently been a trend toward the socalled fast-track approach to peri-operative care, in which the entire

care team is involved in a multi-modal, coordinated effort involving

many different evidence-based methods of hastening post-operative

recovery simultaneously [19]. This has been the standard for most

surgical specialties in Europe [20], where many of these protocols were

developed. Recently, AJOG published a similar fast-track protocol

for gynecological oncology patients undergoing laparotomy [21]. A

retrospective study was performed, looking at length of hospital stay,

readmission rates, and post-operative complications in 880 oncology

patients in Southern California whose post-operative care was dictated

by a fast-track clinical pathway involving seven elements:

PCA/pain control - reduced use of opioids: discontinuation of

PCA in the morning of post-operative day 1, with initiation of

oral pain medication, and use of ketorolac in the case of PO

intolerance or breakthrough pain

Diet - early feeding: clear liquid diet on the morning of postoperative day 1, advanced as tolerated

IV fluids early discontinuation when tolerating PO intake

Ambulation - encouraged on post-operative day 1

Volume 2 Issue 4 1000137

Citation: Katz F, Nelson A (2013) Simple Steps to Hasten Post-Operative Recovery. J Womens Health Care 2: 137. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000137

Page 3 of 3

Urinary bladder drainage - removal of foley catheter on the

morning of post-operative day 1

Flatus/bowel sounds not used as an indication of return to

bowel function or to predict resolution of post-operative ileus

Patient education - extensive pre-operative counseling

In this clinical pathway, patients were discharged on post-operative

day 2 unless otherwise contraindicated, and were given instructions for

continued recuperation at home, including ambulation, non-opioid

pain control, and normal diet. Median length of stay was 2 days (36%

of total study population; another 25% were discharged after 3-5

days), and re-admission rate was 5% (most commonly for surgical site

infections and small bowel obstruction). Older age, higher BMI, higher

EBL, and presence of ovarian cancer were all associated with increased

length of hospital stay. The rate of post-operative complications and

readmission rates were comparable to those previously reported in the

literature.

Several cost-effectiveness analyses have been performed on fasttrack protocols for hysterectomy, with the finding of significant

reduction in hospital costs without compromising patient satisfaction

or complication rates [22].

Conclusions

Early feeding, although associated with increased nausea, has

been shown to shorten time until toleration of diet, facilitating

early discharge and reducing length of hospital stay. Decision

to withhold feeding should be individualized, and in part based

on surgical complications such as bowel injury.

Other methods of preventing prolonged post-operative ileus

include avoiding aggressive mechanical bowel prep preoperatively, reducing use of opioids in favor of NSAIDs,

and using stimulant laxatives (Dulcolax) in addition to stool

softeners such as Colace.

Gum chewing has been shown to hasten return to bowel

function, and may contribute to reducing length of hospital

stay [23,24].

Early ambulation reduces incidence of venous thromboembolic

events and helps psychologically prepare patients for discharge.

No evidence that ambulation hastens return to bowel function.

Early removal of the foley catheter in uncomplicated patients

encourages early ambulation, prevents UTIs, and is not

associated with increased incidence of urinary retention.

Multimodal fast-track approach: while many of the above

methods are only modestly effective when used alone, a

significant improvement can be seen when used in combination,

with the help of the entire patient care team. Even complicated

gynecologic oncology patients can have improved outcomes

with this type of coordinated approach.

References

1. Pearl ML, Valea FA, Fischer M, Mahler L, Chalas E (1998) A randomized

controlled trial of early postoperative feeding in gynecologic oncology patients

undergoing intra-abdominal surgery. Obstet Gynecol 92: 94-97.

2. Pearl ML, Frandina M, Mahler L, Valea FA, DiSilvestro PA, et al. (2002) A

randomized controlled trial of a regular diet as the first meal in gynecologic

oncology patients undergoing intraabdominal surgery. Obstet Gynecol 100:

230-234.

3. Charoenkwan K, Phillipson G, Vutyavanich T (2007) Early versus delayed

J Womens Health Care

ISSN: 2167-0420 JWHC, an open access journal

(traditional) oral fluids and food for reducing complications after major

abdominal gynaecologic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev : CD004508.

4. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ (2002) Early compared with delayed oral fluids and

food after caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev : CD003516.

5. Lewis SJ, Andersen HK, Thomas S (2009) Early enteral nutrition within 24 h of

intestinal surgery versus later commencement of feeding: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 13: 569-575.

6. de Castro SM, van den Esschert JW, van Heek NT, Dalhuisen S, Koelemay

MJ, et al. (2008) A systematic review of the efficacy of gum chewing for the

amelioration of postoperative ileus. Dig Surg 25: 39-45.

7. Story SK, Chamberlain RS (2009) A comprehensive review of evidence-based

strategies to prevent and treat postoperative ileus. Dig Surg 26: 265-275.

8. Person B, Wexner SD (2006) The management of postoperative ileus. Curr

Probl Surg 43: 6-65.

9. Bauer AJ, Boeckxstaens GE (2004) Mechanisms of postoperative ileus.

Neurogastroenterol Motil 16 Suppl 2: 54-60.

10. Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ (1998) Surgical manipulation

of the gut elicits an intestinal muscularis inflammatory response resulting in

postsurgical ileus. Ann Surg 228: 652-663.

11. Luckey A, Livingston E, Tach Y (2003) Mechanisms and treatment of

postoperative ileus. Arch Surg 138: 206-214.

12. Holte K, Sharrock NE, Kehlet H (2002) Pathophysiology and clinical implications

of perioperative fluid excess. Br J Anaesth 89: 622-632.

13. Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramr MR (2001) Efficacy and safety of

patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. A quantitative

systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 45: 795-804.

14. Zingg U, Miskovic D, Pasternak I, Meyer P, Hamel CT, et al. (2008) Effect

of bisacodyl on postoperative bowel motility in elective colorectal surgery: a

prospective, randomized trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 23: 1175-1183.

15. Benoist S, Panis Y, Denet C, Mauvais F, Mariani P, et al. (1999) Optimal

duration of urinary drainage after rectal resection: a randomized controlled trial.

Surgery 125: 135-141.

16. Iwata Y, Mizota Y, Mizota T, Koyama T, Shichino T (2012) Postoperative

continuous intravenous infusion of fentanyl is associated with the development

of orthostatic intolerance and delayed ambulation in patients after gynecologic

laparoscopic surgery. J Anesth 26: 503-508.

17. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Page GG, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R

(1998) Psychological influences on surgical recovery. Perspectives from

psychoneuroimmunology. Am Psychol 53: 1209-1218.

18. Egbert LD, Battit GE, Welch CE, Bartlett MK (1964) Reduction of Postoperative

Pain by Encouragement and instruction of patients. A study of Doctor-Patient

Rapport. N Engl J Med 270: 825-827.

19. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW (2002) Multimodal strategies to improve surgical

outcome. Am J Surg 183: 630-641.

20. Mller C, Kehlet H, Friland SG, Schouenborg LO, Lund C, et al. (2001) Fast

track hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 98: 18-22.

21. Chase DM, Lopez S, Nguyen C, Pugmire GA, Monk BJ (2008) A clinical

pathway for postoperative management and early patient discharge: does it

work in gynecologic oncology? Am J Obstet Gynecol 199: 541.

22. Ghosh K, Downs LS, Padilla LA, Murray KP, Twiggs LB, et al. (2001) The

implementation of critical pathways in gynecologic oncology in a managed care

setting: a cost analysis. Gynecol Oncol 83: 378-382.

23. Ertas IE, Gungorduk K, Ozdemir A, Solmaz U, Dogan A, et al. (2013) Influence

of gum chewing on postoperative bowel activity after complete staging surgery

for gynecological malignancies: A randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol

131: 118-122.

24. Husslein H, Franz M, Gutschi M, Worda C, Polterauer S, et al. (2013)

Postoperative gum chewing after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery: a

randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 122: 85-90.

Citation: Katz F, Nelson A (2013) Simple Steps to Hasten Post-Operative

Recovery. J Womens Health Care 2: 137. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000137

Volume 2 Issue 4 1000137

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Fracture-Dislocation of The Ankle With Fixed Displacement of The Fibula Behind The TibiaDocument4 pagesFracture-Dislocation of The Ankle With Fixed Displacement of The Fibula Behind The TibiaIbnu SyahNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Adductor Canal Block For Postoperative Pain Relief in Knee Surgeries A Review Article 2155 6148 1000578Document4 pagesAdductor Canal Block For Postoperative Pain Relief in Knee Surgeries A Review Article 2155 6148 1000578Ibnu SyahNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Allergy Prevention in The Future of NationDocument43 pagesAllergy Prevention in The Future of NationIbnu SyahNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Impact of Postoperative Pain On Early Ambulation After Hip FractureDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Postoperative Pain On Early Ambulation After Hip FractureIbnu SyahNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Anesthesia & Analgesia-Nov05Document336 pagesAnesthesia & Analgesia-Nov05Ibnu SyahNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Adductor Canal Block For Postoperative Pain Relief in Knee Surgeries A Review Article 2155 6148 1000578Document4 pagesAdductor Canal Block For Postoperative Pain Relief in Knee Surgeries A Review Article 2155 6148 1000578Ibnu SyahNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- TORCH Repro 2012Document44 pagesTORCH Repro 2012Ibnu SyahNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- SKILL LAB LBM 2 Zung Depression Rating ScaleDocument2 pagesSKILL LAB LBM 2 Zung Depression Rating ScaleIbnu SyahNo ratings yet

- JUU Speech by ARDDocument8 pagesJUU Speech by ARDBriliansy MulyantoNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Dwarfism: Navigation Search Dwarf (Germanic Mythology) DwarfDocument15 pagesDwarfism: Navigation Search Dwarf (Germanic Mythology) DwarfManzano JenecaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Structure of KidneysDocument36 pagesStructure of KidneysunisoldierNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- MBFHI Self AppraisalDocument26 pagesMBFHI Self AppraisalKarz KaraoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Ability of Prehabilitation To Influence Postoperative Outcome After Intra-Abdominal Operation: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument13 pagesThe Ability of Prehabilitation To Influence Postoperative Outcome After Intra-Abdominal Operation: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisHAriNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Femoral Block Vs Adductor Canal Block: Regional Analgesia For Total Knee ArthroplastyDocument10 pagesFemoral Block Vs Adductor Canal Block: Regional Analgesia For Total Knee ArthroplastyStanford AnesthesiaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome: Information Leaflet OnDocument8 pagesTwin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome: Information Leaflet Onshona SharupaniNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Or JournalDocument2 pagesOr JournalNathaniel PulidoNo ratings yet

- Royal Crescent Practice Brocher 12pp March 2010 PrintDocument12 pagesRoyal Crescent Practice Brocher 12pp March 2010 PrintyarleyNo ratings yet

- Mallampati 0 2001Document3 pagesMallampati 0 2001Eugenio Daniel Martinez HurtadoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Diarrhea - Toddlers PDFDocument1 pageDiarrhea - Toddlers PDFNida AwaisNo ratings yet

- The Five Tibetan RitesDocument12 pagesThe Five Tibetan RitesFlorea Eliza100% (1)

- What Is An Intravenous Pyelogram (IVP) ? How Should I Prepare?Document4 pagesWhat Is An Intravenous Pyelogram (IVP) ? How Should I Prepare?vindictive666No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Inferior Thoracic ApertureDocument7 pagesThoracic Outlet Syndrome Inferior Thoracic ApertureerilarchiNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Acute Gout: A Clinical Practice Guideline From The American College of PhysiciansDocument8 pagesDiagnosis of Acute Gout: A Clinical Practice Guideline From The American College of PhysiciansRgm UyNo ratings yet

- Essential Intra Natal Care 11aiDocument78 pagesEssential Intra Natal Care 11aiDr Ankush VermaNo ratings yet

- Structural and Dynamic Bases of Hand Surgery by Eduardo Zancolli 1969Document1 pageStructural and Dynamic Bases of Hand Surgery by Eduardo Zancolli 1969khox0% (1)

- Voluson E10 BrochureDocument8 pagesVoluson E10 BrochureJavier VergaraNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

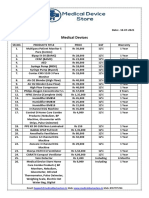

- Medical Device Store Products CatalogueDocument3 pagesMedical Device Store Products CatalogueWasim KhatibNo ratings yet

- Ethical and Legal Issues in Reproductive HealthDocument4 pagesEthical and Legal Issues in Reproductive HealthBianca_P0pNo ratings yet

- 380 (Olive Peart) Lange QA Mammography Examination PDFDocument186 pages380 (Olive Peart) Lange QA Mammography Examination PDFGabriel Callupe100% (1)

- Hemorrhoids: What Are Hemorroids?Document2 pagesHemorrhoids: What Are Hemorroids?Igor DemićNo ratings yet

- English - All Instruction Mannual-20220412-VietnamDocument9 pagesEnglish - All Instruction Mannual-20220412-VietnamHRD Wijaya Mitra HusadaNo ratings yet

- Pneumonperitoneum A Review of Nonsurgical Causes PDFDocument7 pagesPneumonperitoneum A Review of Nonsurgical Causes PDFDellysa Eka Nugraha TNo ratings yet

- Provincial Drug ScheduleDocument16 pagesProvincial Drug ScheduleSamMansuriNo ratings yet

- High School Argumentative Essay TopicsDocument5 pagesHigh School Argumentative Essay Topicslpuaduwhd100% (2)

- CholangiocarcinomaDocument9 pagesCholangiocarcinomaloloalpsheidiNo ratings yet

- ACOG Guidelines For Exercise During PregnancyDocument13 pagesACOG Guidelines For Exercise During Pregnancypptscribid100% (1)

- Anaesthesia Revised A5Document720 pagesAnaesthesia Revised A5barn003100% (1)

- Acupuncture Imaging 31 40 PDFDocument10 pagesAcupuncture Imaging 31 40 PDFmamun31No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)