Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abington Heights School District v. Speedspace Corporation, 693 F.2d 284, 3rd Cir. (1982)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abington Heights School District v. Speedspace Corporation, 693 F.2d 284, 3rd Cir. (1982)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

693 F.

2d 284

ABINGTON HEIGHTS SCHOOL DISTRICT, Appellant,

v.

SPEEDSPACE CORPORATION, Appellee.

No. 82-3199.

United States Court of Appeals,

Third Circuit.

Argued Sept. 29, 1982.

Decided Nov. 17, 1982.

1

Joseph P. Lenahan, (argued), Lenahan & Dempsey, Scranton, Pa., for appellant.

Oldrich Foucek, III, Thomas C. Sadler, Jr., (argued), Butz, Hudders & Tallman,

Allentown, Pa., for appellee.

Before ALDISERT and HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges and MEANOR,*

District Judge.

OPINION OF THE COURT

4

MEANOR, District Judge.

On June 1, 1976 a fire occurred upon premises owned by the plaintiffappellant. This diversity action was begun on June 27, 1979 naming appellee

Speedspace Corporation, a California corporation, and Universal

Manufacturing Corp. as defendants. The complaint sought damages arising out

of the fire. It asserted that Speedspace had negligently designed and constructed

the elementary school building in which the fire took place and that Universal

had supplied defective fluorescent light ballasts.

After some difficulty in effecting service upon it, Speedspace appeared and

moved to dismiss upon the ground that as a California corporation having been

dissolved on December 31, 1978, under the law of that state it was no longer

amenable to suit. In May, 1980 the district court, relying upon Ray v. Alad

Corp., 19 Cal.3d 22, 560 P.2d 3, 136 Cal.Rptr. 574 (1977) held that, under the

law of California, once a certificate of dissolution is filed, corporate existence

ceases and there is no longer amenability to suit.

7

On the heels of this ruling, the plaintiff moved for reconsideration, contending

that it had just discovered that prior to dissolution Speedspace had been a

subsidiary of Potlach Corporation and that the dissolution may have been a

"merger" between Potlach and its subsidiary. Plaintiff did not move to add

Potlach as a defendant. Reconsideration was denied, on the ground that

imposition of liability upon Potlach as the parent or successor could not be

accomplished by re-instituting the complaint against Speedspace, a "non-entity

for the purpose of suit."

Plaintiff attempted to appeal the above rulings, but the appeal was dismissed on

April 24, 1981 for want of a final judgment, since the case remained open as to

Universal. Subsequently, Universal settled and secured a dismissal, thus

rendering final and appealable the previous entry of judgment in favor of

Speedspace.

We believe that the district court misread Ray v. Alad Corp. That case did not

involve the question whether a dissolved corporation remained subject to suit.

The defendant there, Alad II, had purchased the assets of the dissolved Alad I,

without assuming any liabilities pertinent to the product liability claim

advanced by plaintiff arising out of his use of a product manufactured by Alad

I. Alad II simply continued the business of Alad I. Under these circumstances,

the Supreme Court of California imposed successor liability upon Alad II with

respect to product liability arising out of its predecessor's manufacture.1 In that

case the California court was not confronted with an attempt to sue the

dissolved Alad I. The remarks of the court on which the district court relied did

not go to the question whether, under California law, a dissolved corporation

was susceptible to being sued. Those remarks, rather, were directed to the

futility of collection after dissolution, liquidation and distribution. This futility,

in turn, played a part in the policy decision to place product liability upon a

successor corporation which had purchased only assets without assuming

liabilities.

10

Rule 17(b), F.R.Civ.P. provides in pertinent part: "The capacity of a corporation

to sue or be sued shall be determined by the law under which it was organized."

Hence, we must turn to California law to determine whether Speedspace,

though dissolved, remains subject to suit on account of an asserted predissolution tort. The pertinent provisions of the applicable California statute are

set forth below.2

11

In our judgment the result in the matter before us is controlled by North

11

In our judgment the result in the matter before us is controlled by North

American Asbestos v. Superior Court, 128 Cal.App.3d 138, 179 Cal.Rptr. 889

(1982). There, personal injury claimants brought suit against a dissolved Illinois

corporation. Illinois law provided that a dissolved corporation could be sued

within two years of dissolution. The suits before the California Court of Appeal

had been brought more than two years following the date of dissolution. The

plaintiff, therefore, argued that California law should apply. Although the

Court rejected the application of California law and applied Illinois law instead,

in discussing section 2010 of the California Corporation Code it stated:

12

It is clear that the California survival law does not apply to suits against

dissolved foreign corporations. California Corporations Code section 2010

provides that '(a) corporation which is dissolved nevertheless continues to exist

for the purpose of winding up its affairs, prosecuting and defending actions by

or against it ...." It also provides that "[n]o action or proceeding to which a

corporation is a party abates by the dissolution of the corporation or by reason

of proceedings for winding up and dissolution thereof." Thus, there is no time

limitation for suing a dissolved corporation for injuries arising out of its predissolution activities.

13

If section 2010 applies to foreign corporations as well as to domestic

corporations, then application of California law would permit these lawsuits to

continue. However, section 2010 does not apply to a foreign corporation. North

American Asbestos, 128 Cal.App.3d at 144, 179 Cal.Rptr. 889.

14

In light of the language quoted above, we hold that under California law,

Speedspace, as a dissolved corporation, is subject to suit arising out of its predissolution activities, with the only time bar being that of an applicable general

statute of limitations.

15

The judgment under review will be reversed and the matter remanded for

proceedings consistent with this opinion. Costs taxed in favor of appellant.3

Hon. H. Curtis Meanor, United States District Judge for the District of New

Jersey, sitting by designation

Ray v. Alad Corp. is consistent with our decision imposing successor liability

in Knapp v. North American Rockwell Corp., 506 F.2d 361 (3d Cir.1974)

Section 2010 of the California General Corporation Law provides:

(a) A corporation which is dissolved nevertheless continues to exist for the

purpose of winding up its affairs, prosecuting and defending actions by or

against it and enabling it to collect and discharge obligations, dispose of and

convey its property and collect and divide its assets, but not for the purpose of

continuing business except so far as necessary for the winding up thereof.

(b) No action or proceeding to which a corporation is a party abates by the

dissolution of the corporation or by reason of proceedings for winding up and

dissolution thereof.

3

To date, plaintiff has not attempted to amend to add Potlach Corporation as a

defendant. If such a motion is made promptly upon remand, we direct that it be

granted. Questions of successor liability, relation back and the statute of

limitations can be resolved after Potlach is properly joined and served

At oral argument counsel for appellant, in response to a question from the

court, stated that he was representing the interests of a subrogated fire insurance

carrier. Attention is called to the real party in interest provisions of rule 17(a)

F.R.Civ.P. See United States v. Aetna Surety Co., 338 U.S. 366, 70 S.Ct. 207,

94 L.Ed. 171 (1949) and Virginia Electric & Power Co. v. Westinghouse Elec.

Corp., 485 F.2d 78 (4th Cir.1973).

You might also like

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Guarantee Acceptance Corporation, Debtor-Appellant v. Fidelity Mortgage Investors, 544 F.2d 449, 10th Cir. (1976)Document5 pagesIn The Matter of Guarantee Acceptance Corporation, Debtor-Appellant v. Fidelity Mortgage Investors, 544 F.2d 449, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kawananokoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349 (1907)Document10 pagesKawananokoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349 (1907)Don VillegasNo ratings yet

- Fines Hillard v. First Financial Insurance Company, 968 F.2d 1214, 1st Cir. (1992)Document4 pagesFines Hillard v. First Financial Insurance Company, 968 F.2d 1214, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mclouth Steel Corp. v. Mesta Machine Co. FOSTER Et Al. v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co. (Landis Tool Co., Third-Party Defendant)Document6 pagesMclouth Steel Corp. v. Mesta Machine Co. FOSTER Et Al. v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co. (Landis Tool Co., Third-Party Defendant)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Home Indemnity Company v. The United States, v. Gerald P. GRACE, Trustee in Bankruptcy of Abco Finance Company, Third-PartyDocument3 pagesHome Indemnity Company v. The United States, v. Gerald P. GRACE, Trustee in Bankruptcy of Abco Finance Company, Third-PartyScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Case ChartDocument14 pagesCiv Pro Case ChartMadeline Taylor DiazNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 914 F.2d 1271 18 Fed.R.Serv.3d 139: United States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitDocument11 pages914 F.2d 1271 18 Fed.R.Serv.3d 139: United States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- J. Gutierrez, Jr. - Petition For Review On Certiorari: Rebollido V. CaDocument3 pagesJ. Gutierrez, Jr. - Petition For Review On Certiorari: Rebollido V. CaCamille BritanicoNo ratings yet

- Writing ExercisesDocument7 pagesWriting ExercisesCyrusNo ratings yet

- American Power & Light Co. v. Securities and Exchange Commission. Securities and Exchange Commission v. Okin, 325 U.S. 385 (1945)Document10 pagesAmerican Power & Light Co. v. Securities and Exchange Commission. Securities and Exchange Commission v. Okin, 325 U.S. 385 (1945)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- DiMaio Family Pizza v. The Charter, 448 F.3d 460, 1st Cir. (2006)Document7 pagesDiMaio Family Pizza v. The Charter, 448 F.3d 460, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The First CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- William Esbitt, As Receiver of The Assets and Property of First Discount Corp. v. Dutch-American Mercantile Corp., 335 F.2d 141, 1st Cir. (1964)Document4 pagesWilliam Esbitt, As Receiver of The Assets and Property of First Discount Corp. v. Dutch-American Mercantile Corp., 335 F.2d 141, 1st Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Illinois Ex Rel. Gordon v. Campbell, 329 U.S. 362 (1946)Document13 pagesIllinois Ex Rel. Gordon v. Campbell, 329 U.S. 362 (1946)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Arnold Hall v. Piccio, 86 Phil. 634 (1950)Document3 pagesArnold Hall v. Piccio, 86 Phil. 634 (1950)inno KalNo ratings yet

- United States v. Fleet Bank, 288 F.3d 22, 1st Cir. (2002)Document30 pagesUnited States v. Fleet Bank, 288 F.3d 22, 1st Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- N. L. Wymard and George L. Stark, Receivers of Kemmel & Co., Inc., Debtor v. McCloskey & Co., Inc., 342 F.2d 495, 3rd Cir. (1965)Document14 pagesN. L. Wymard and George L. Stark, Receivers of Kemmel & Co., Inc., Debtor v. McCloskey & Co., Inc., 342 F.2d 495, 3rd Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Feb 17Document29 pagesFeb 17Bea AlduezaNo ratings yet

- Cable v. United States Life Ins. Co., 191 U.S. 288 (1903)Document9 pagesCable v. United States Life Ins. Co., 191 U.S. 288 (1903)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Patty Precision, A Corporation v. Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Co., General Electric Company, and Tools Capital Corporation, 742 F.2d 1260, 10th Cir. (1984)Document8 pagesPatty Precision, A Corporation v. Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Co., General Electric Company, and Tools Capital Corporation, 742 F.2d 1260, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Friends of Earth v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, 528 U.S. 167 (2000)Document35 pagesFriends of Earth v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, 528 U.S. 167 (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Lafayette Ins. Co. v. FRENCH, 59 U.S. 404 (1856)Document6 pagesThe Lafayette Ins. Co. v. FRENCH, 59 U.S. 404 (1856)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Merritt A. (Sonny) Walker, Jr. v. Pacific Basin Trading Company, A Wholly Owned Subsidiary of Western Farm Service, Inc., A Delaware Corporation, 536 F.2d 344, 10th Cir. (1976)Document5 pagesMerritt A. (Sonny) Walker, Jr. v. Pacific Basin Trading Company, A Wholly Owned Subsidiary of Western Farm Service, Inc., A Delaware Corporation, 536 F.2d 344, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eye Site Incv BlackburnDocument3 pagesEye Site Incv BlackburnCristobal MillanNo ratings yet

- Amphibious Partners LLC v. Redman, 10th Cir. (2010)Document13 pagesAmphibious Partners LLC v. Redman, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- C.O.D.E., Inc. v. Interstate Commerce Commission and United States of America, 768 F.2d 1210, 10th Cir. (1985)Document4 pagesC.O.D.E., Inc. v. Interstate Commerce Commission and United States of America, 768 F.2d 1210, 10th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Thomas Ryan and Beverly Eileen Ryan v. International Union of Operating Engineers, Local 675, 794 F.2d 641, 11th Cir. (1986)Document9 pagesThomas Ryan and Beverly Eileen Ryan v. International Union of Operating Engineers, Local 675, 794 F.2d 641, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lafayette v. FrenchDocument6 pagesLafayette v. FrenchbenratzingNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Colonial Penn Group, Inc., and Bay Loan and Investment Bank v. Colonial Deposit Company, 834 F.2d 229, 1st Cir. (1987)Document13 pagesColonial Penn Group, Inc., and Bay Loan and Investment Bank v. Colonial Deposit Company, 834 F.2d 229, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Product Engineering and Manufacturing, Inc. v. Andrew F. Barnes, 424 F.2d 42, 10th Cir. (1970)Document4 pagesProduct Engineering and Manufacturing, Inc. v. Andrew F. Barnes, 424 F.2d 42, 10th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Motion To Strike in CaliforniaDocument3 pagesMotion To Strike in CaliforniaStan Burman80% (5)

- 195 - Atlantic Mutual Insurance vs. Cebu StevedoringDocument2 pages195 - Atlantic Mutual Insurance vs. Cebu Stevedoringmimiyuki_No ratings yet

- United States v. Fidelity Capital Corporation, A Georgia Corporation, Commonwealth Mortgage Corporation of America, Intervenor-Appellee, 933 F.2d 949, 11th Cir. (1991)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Fidelity Capital Corporation, A Georgia Corporation, Commonwealth Mortgage Corporation of America, Intervenor-Appellee, 933 F.2d 949, 11th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Angelo GUERRINO, Philip Deodati, Dr. A. P. Engemi, Albert J. Guerra, E. B. Fleming Company, Appellants, v. Ohio Casualty Insurance CompanyDocument5 pagesAngelo GUERRINO, Philip Deodati, Dr. A. P. Engemi, Albert J. Guerra, E. B. Fleming Company, Appellants, v. Ohio Casualty Insurance CompanyScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. United States Vanadium Corporation, Electro Metallurgical Company and Electro Metallurgical Sales Corporation, 230 F.2d 646, 10th Cir. (1956)Document5 pagesUnited States v. United States Vanadium Corporation, Electro Metallurgical Company and Electro Metallurgical Sales Corporation, 230 F.2d 646, 10th Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lamp Liquors, Inc., A Wyoming Corporation v. Adolph Coors Company, A Colorado Corporation, and Cheyenne Beverage, Inc., A Wyoming Corporation, 563 F.2d 425, 10th Cir. (1977)Document12 pagesLamp Liquors, Inc., A Wyoming Corporation v. Adolph Coors Company, A Colorado Corporation, and Cheyenne Beverage, Inc., A Wyoming Corporation, 563 F.2d 425, 10th Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Digests (Sec1 - 10) UPDATED 112912Document95 pagesCorporation Law Digests (Sec1 - 10) UPDATED 112912Paul Angelo TombocNo ratings yet

- Angora Enterprises, Inc., and Joseph Kosow v. Condominium Association of Lakeside Village, Inc., 796 F.2d 384, 11th Cir. (1986)Document7 pagesAngora Enterprises, Inc., and Joseph Kosow v. Condominium Association of Lakeside Village, Inc., 796 F.2d 384, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument24 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 873 F.2d 1440 Unpublished Disposition: United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pages873 F.2d 1440 Unpublished Disposition: United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joseph M. Shealy, Jr. v. Challenger Manufacturing Company, Inc., 304 F.2d 102, 4th Cir. (1962)Document9 pagesJoseph M. Shealy, Jr. v. Challenger Manufacturing Company, Inc., 304 F.2d 102, 4th Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Division of Employment Security v. United States of America, in The Matter of Projectron Corporation, Bankrupt, 261 F.2d 449, 1st Cir. (1958)Document3 pagesCommonwealth of Massachusetts, Division of Employment Security v. United States of America, in The Matter of Projectron Corporation, Bankrupt, 261 F.2d 449, 1st Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 8-31-21 9. Velayo v. Shell, G.R. No. L-7817Document7 pages8-31-21 9. Velayo v. Shell, G.R. No. L-7817Pepper PottsNo ratings yet

- Church v. Attorney General VA, 4th Cir. (1997)Document10 pagesChurch v. Attorney General VA, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Home Insurance V Eastern Shipping LinesDocument5 pagesHome Insurance V Eastern Shipping LinesAntonio RebosaNo ratings yet

- Special Torts (Human Relations)Document42 pagesSpecial Torts (Human Relations)viktoriavilloNo ratings yet

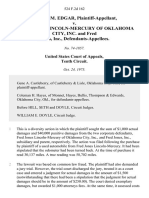

- Virginia M. Edgar v. Fred Jones Lincoln-Mercury of Oklahoma City, Inc. and Fred Jones, Inc., 524 F.2d 162, 10th Cir. (1975)Document7 pagesVirginia M. Edgar v. Fred Jones Lincoln-Mercury of Oklahoma City, Inc. and Fred Jones, Inc., 524 F.2d 162, 10th Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Case Digest in COLDocument42 pagesCase Digest in COLDominic M. CerbitoNo ratings yet

- St. Paul Fire & Marine Insurance Company v. Advanced Interventional Systems, Incorporated, 21 F.3d 424, 4th Cir. (1994)Document6 pagesSt. Paul Fire & Marine Insurance Company v. Advanced Interventional Systems, Incorporated, 21 F.3d 424, 4th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Director of Lands V Ca - 276scra276 - DIGDocument3 pagesDirector of Lands V Ca - 276scra276 - DIGfjl_302711No ratings yet

- Bleich, E. (2011) - The Rise of Hate Speech and Hate Crime Laws in Liberal DemocraciesDocument19 pagesBleich, E. (2011) - The Rise of Hate Speech and Hate Crime Laws in Liberal DemocraciesJr Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- For NBW Cancellation Presence of Accused Not Required Before MagistrateDocument5 pagesFor NBW Cancellation Presence of Accused Not Required Before MagistrateapndesaiNo ratings yet

- Capital Gains Tax Ruled Constitutional by Washington State Supreme CourtDocument76 pagesCapital Gains Tax Ruled Constitutional by Washington State Supreme CourtGeekWireNo ratings yet

- I Specpro DigestsDocument16 pagesI Specpro DigestsPJ SLSRNo ratings yet

- Ellis S Frison IRS DecisionDocument5 pagesEllis S Frison IRS DecisionLilly EllisNo ratings yet

- Cybercrime ActDocument5 pagesCybercrime ActRhon NunagNo ratings yet

- Workshop Paper On "Plaint"Document57 pagesWorkshop Paper On "Plaint"Jay KothariNo ratings yet

- 2010 Crim Bar QuestionsDocument13 pages2010 Crim Bar QuestionsLaika CorralNo ratings yet

- Esso Standard V CIRDocument2 pagesEsso Standard V CIRSui100% (1)

- Sulpicio Lines v. CADocument2 pagesSulpicio Lines v. CARhea BarrogaNo ratings yet

- Sux October 22Document51 pagesSux October 22JuralexNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No. 10667 Philippine Competition ActDocument9 pagesRepublic Act No. 10667 Philippine Competition Actbelbel08No ratings yet

- Remedial Law PreliminariesDocument12 pagesRemedial Law PreliminariesLex LimNo ratings yet

- Atok Big Wedge Company Vs GisonDocument4 pagesAtok Big Wedge Company Vs GisonMac Duguiang Jr.No ratings yet

- Japan ConstitutionDocument36 pagesJapan ConstitutionSenthil G KumarNo ratings yet

- Introduced Senator Gregorio EL. Honasan: It Its IsDocument10 pagesIntroduced Senator Gregorio EL. Honasan: It Its IsJerale CarreraNo ratings yet

- Punzalan vs. Punzalan Info Comp2Document4 pagesPunzalan vs. Punzalan Info Comp2Loucille Abing LacsonNo ratings yet

- ReductionDocument2 pagesReductionPeter Carlo DavidNo ratings yet

- Funa Vs ChairmanDocument26 pagesFuna Vs Chairmanracel joyce gemotoNo ratings yet

- Persons Case Digest PerezDocument29 pagesPersons Case Digest PerezGiselle QuilatanNo ratings yet

- Metrobank v. CPR Promotions and Marketing, G.R. No. 200567, 22 June 2015Document13 pagesMetrobank v. CPR Promotions and Marketing, G.R. No. 200567, 22 June 2015Christopher Julian ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Board Resolution Appointing An AuditorDocument1 pageBoard Resolution Appointing An AuditorHenry IhedughinukaNo ratings yet

- People vs. GorospeDocument17 pagesPeople vs. GorospeAnimalNo ratings yet

- Appellees Brief Asialink V MadriagaDocument53 pagesAppellees Brief Asialink V MadriagaDence Cris RondonNo ratings yet

- Sonubai Yeshwant Jadhav V Bala Govinda Yadav AIR 1983 Bom 156 Srinivasa Aiyar Vs Saraswathi Ammal, 1951 AIR 1952 Mad 193, (1951) 2 MLJ 649Document3 pagesSonubai Yeshwant Jadhav V Bala Govinda Yadav AIR 1983 Bom 156 Srinivasa Aiyar Vs Saraswathi Ammal, 1951 AIR 1952 Mad 193, (1951) 2 MLJ 649haydeeirNo ratings yet

- PACU v. Secretary of EducationDocument3 pagesPACU v. Secretary of EducationFidela Maglaya100% (4)

- Provisional Remedies Midterm PDFDocument46 pagesProvisional Remedies Midterm PDFPhil JaramilloNo ratings yet

- 1meralco V Lim - Habeas DataDocument1 page1meralco V Lim - Habeas DataIanNo ratings yet

- REVISED MR of Hans Christian Romulo ChavezDocument3 pagesREVISED MR of Hans Christian Romulo ChavezHans Christian ChavezNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (560)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistFrom EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesFrom EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1635)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentFrom EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4125)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Summary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeFrom EverandSummary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryFrom EverandThe Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (882)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (233)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1458)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Seven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your DreamsFrom EverandSeven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your DreamsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1549)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelFrom EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path to True Christian JoyFrom EverandThe Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path to True Christian JoyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (192)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Bedtime Stories for Stressed Adults: Sleep Meditation Stories to Melt Stress and Fall Asleep Fast Every NightFrom EverandBedtime Stories for Stressed Adults: Sleep Meditation Stories to Melt Stress and Fall Asleep Fast Every NightRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (124)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeFrom EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)