Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Carl D. Citron v. Aro Corporation, A Foreign Corporation, 377 F.2d 750, 3rd Cir. (1967)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Carl D. Citron v. Aro Corporation, A Foreign Corporation, 377 F.2d 750, 3rd Cir. (1967)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

377 F.

2d 750

Carl D. CITRON, Appellant,

v.

ARO CORPORATION, a Foreign Corporation.

No. 15643.

United States Court of Appeals Third Circuit.

Argued May 19, 1966.

Decided May 11, 1967.

Frank W. Ittel, Pittsburgh, Pa. (Frank W. Ittel, Jr., Charles C. Cohen,

Reed, Smith, Shaw & McClay, Pittsburgh, Pa., Edward M. Citron,

Pittsburgh, Pa., on the brief), for appellant.

George B. Newitt, Chicago, Ill. (J. Robert Maxwell, Gerald W. Weaver,

Maxwell, Huss & Weaver, Pittsburgh, Pa., Bair, Freeman & Molinare,

Chicago, Ill., on the brief), for appellee.

Before STALEY, Chief Judge, and McLAUGHLIN and SMITH, Circuit

Judges.

OPINION OF THE COURT

WILLIAM F. SMITH, Circuit Judge.

This is a civil action in which the plaintiff, as assignee of the rights of one

David Roth, sought damages, an accounting for profits, and an injunction. The

complaint stated three separate claims for relief alleging (1) breach of a

confidential relationship and the unlawful conversion of a trade secret, the

subject matter of which was a surgical instrument; (2) conspiracy to violate

certain fiduciary obligations owned to the assignor by reason of an agreement;

and (3) fraud in the prosecution of a patent application covering the said

surgical instrument. In addition to the usual denials of the pertinent allegations

of the complaint the defendant's answer contained a counterclaim based upon

trade libel. The present appeal is from a judgment in favor of the defendant

entered on the jury's answers to 16 special interrogatories. There is no appeal

from the judgment in favor of the plaintiff on the counterclaim.

The plaintiff urges reversal of the judgment on several grounds but his main

argument is that the manner in which the trial was conducted was so highly

prejudicial to his case as to amount to a denial of due process. The validity of

this argument must be measured against the background of the trial as a whole:

the complexity of the litigation; the length of the trial; the quantity of evidence

received; and, the difficulty of the task which confronted the jury.

We are convinced from our review of the voluminous record before us that the

case was a difficult one for the jury not only because of the length of the trial

but also because of the multiplicity and the complexities of the issues involved.

The determination of these issues required the appliction of legal principles

with which the average juror cannot be expected to be familiar. The difficulty

of the task which confronted the jury is indicated by the magnitude of the

record. There are reproduced in the Appendix more than 4000 pages of

testimony given by 21 witnesses, and close to 200 documentary exhibits, many

of them voluminous. These include both patents and prior art references offered

in defense of the trade secret claim.

The actual trial of this case, exclusive of the time necessarily devoted to the

hearing of motions, required 32 full days but moved forward intermittently and

sporadically for a period of three months, from January 27 to April 29, 1965,

when the case was finally submitted to the jury. During this period the trial,

and particularly the presentation of the plaintiff's evidence, was interrupted by

periodic recesses. The first recess of five days was granted at the request of the

defendant, without objection by the plaintiff, after only three days of trial. This

was later followed by two intermissions, each of one day's duration.

The recess, which may have adversely affected the case of the plaintiff most

seriously, was one of 11 days, exclusive of Saturdays and Sundays, declared at

the close of court on February 25, when, for all practical purposes, the

presentation of the plaintiff's evidence had been concluded. This intermission

was ordered sua sponte by the trial judge and for his own accommodation. The

trial was resumed on the morning of March 15, and thereafter continued

without interruption for 19 days, during which the defendant presented its

evidence and concluded its case. Thereafter the jury was in recess from April 9

to April 22; during this period several days were devoted to hearing arguments

on the court's proposed jury instructions and the request for instructions by

counsel. The case was finally submitted to the jury on April 29, fully two

months after the close of the plaintiff's evidence.

We recognize at the outset that in the trial of the protracted case by a jury, a

plaintiff is usually under a tactical disadvantage incident to the accepted order

of proof. Such a disadvantage may be unavoidable but it is considerably

minimized if the trial is moved along with reasonable continuity so as to permit

the orderly and intelligible presentation of testimony. Prolonged recesses, such

as those which characterized the trial of this case, are not warranted except

where the exigencies are such as to make them imperative.

7

The presentation of the plaintiff's evidence, interrupted by eight days of

intermission, required but eleven days. At the close of this evidence on

February 25, the trial was adjourned until March 15. It can be reasonably

assumed that during the adjournment the jurors returned to their usual

employment and became occupied in their own affairs. After the trial resumed

on March 15, the jury heard 19 days of testimony offered by the defendant

without interruption. The uncertainty of memory being what it is ordinarily, it

would be unreasonable to expect that under the circumstances here present the

jurors would retain a completely revivable grasp of eleven days of testimony

offered by the plaintiff more than two months before the case was finally

submitted to them for consideration. Absent such a grasp the jury was in no

position to adequately weigh the testimony offered by the plaintiff against that

offered by the defendant. This the jurors were required to do if they were to

arrive at a fair and just verdict.

We are persuaded by our review of the record as a whole that the manner in

which the trial of this case was conducted was erroneous. However, the

question for decision is whether the error may be disregarded as harmless in the

absence of an affirmative showing of prejudice. We think not. We believe that

the trial was conducted in a manner which in its ultimate effect was distinctly

favorable to the defendant and decidedly unfavorable to the plaintiff.

Since the error was one related to the substantial rights of the plaintiff, and

prejudice was clearly within the range of possibility, a demonstration of

prejudice was not required. Snyder v. Lehigh Valley Railroad Company, 245

F.2d 112, 115 (3rd Cir. 1957). It is the settled rule that an error 'which relates to

the substantial rights of a party is ground for reversal unless it affirmatively

appears from the whole record that it was not prejudicial.' McCandless v.

United States, 298 U.S. 342, 347, 348, 56 S.Ct. 764, 766, 80 L.Ed. 1205 (1936)

and the cases therein cited; Sears v. Southern Pacific Company, 313 F.2d 498,

503 (9th Cir. 1963). It did not so appear in the instant case.

10

It must be conceded, as the defendant argues, that the plaintiff interposed no

objection to the prolonged recesses. The plaintiff's failure to object, although

not completely excusable, is understandable. On the second day of trial the

judge, referring to a contemplated trip, announced:

11

'I have had this planned for many months and I am not going to forget it for this

case or any other case * * *. I am leaving this city on February 25th and I will

not be back until March 15th, so you can plan your affairs accordingly.'

12

To require an objection after such an emphatic announcement would seem to

place an undue emphasis on form.

13

However, the absence of timely objection does not necessarily preclude the

consideration of error which may have resulted in a miscarriage of justice.

Pritchard v. Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, 350 F.2d 479, 486 (3rd Cir.

1965) cert. den. 382 U.S. 987, 86 S.Ct. 549, 15 L.Ed.2d 475. We believe that

the error in this case adversely affected the right of the plaintiff to a fair and

impartial trial.

14

The judgment of the court below will be reversed and the action will be

remanded with a direction that a new trial be ordered.

You might also like

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Beat Lawyers at Their Own Game: Deaver Brown, AuthorDocument31 pagesBeat Lawyers at Their Own Game: Deaver Brown, Authoramm7100% (1)

- Sample Motion To Vacate Judgment Under CCP Section 473 For CaliforniaDocument4 pagesSample Motion To Vacate Judgment Under CCP Section 473 For CaliforniaStan Burman57% (7)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Original Thirteenth AmendmentDocument4 pagesThe Original Thirteenth Amendmentruralkiller100% (3)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rule 76, Section 1: Voluntarily Prepared Transfer of Thing or RightDocument6 pagesRule 76, Section 1: Voluntarily Prepared Transfer of Thing or RightAndrew NavarreteNo ratings yet

- 003 Angelita Manzano vs. CADocument4 pages003 Angelita Manzano vs. CAMarvin De LeonNo ratings yet

- Rios V Cartagena - Big Pun's Widow v. Fat JoeDocument24 pagesRios V Cartagena - Big Pun's Widow v. Fat JoeMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Cases 1Document56 pagesCriminal Law Cases 1Charls BagunuNo ratings yet

- Nenita Corp Vs GalaboDocument3 pagesNenita Corp Vs GalaboMarianne Ko50% (2)

- IRS Tax Court Reply To Motion To Dismiss-CompleteDocument97 pagesIRS Tax Court Reply To Motion To Dismiss-CompleteJeff Maehr100% (1)

- Credit - Loan DigestDocument12 pagesCredit - Loan DigestAlyssa Fabella ReyesNo ratings yet

- Abellana Vs People DigestDocument1 pageAbellana Vs People DigestAlex CabangonNo ratings yet

- Rayo lacks standing to annul Metrobank foreclosureDocument2 pagesRayo lacks standing to annul Metrobank foreclosureCzarDuranteNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of The Witness Charles G. Berry, 521 F.2d 179, 10th Cir. (1975)Document9 pagesIn The Matter of The Witness Charles G. Berry, 521 F.2d 179, 10th Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dominick Baccollo, 725 F.2d 170, 2d Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Dominick Baccollo, 725 F.2d 170, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Young & Simon, Incorporated Maury Young and Isabel Young v. Merritt Savings & Loan, Incorporated Gilbert H. Cullen Milton Sommers, 672 F.2d 401, 4th Cir. (1982)Document3 pagesYoung & Simon, Incorporated Maury Young and Isabel Young v. Merritt Savings & Loan, Incorporated Gilbert H. Cullen Milton Sommers, 672 F.2d 401, 4th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 311, Docket 33019Document10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 311, Docket 33019Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Charles Smith and Irene Smith v. United States of America and David M. Satz, JR., United States Attorney For The District of New Jersey, 377 F.2d 739, 3rd Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesCharles Smith and Irene Smith v. United States of America and David M. Satz, JR., United States Attorney For The District of New Jersey, 377 F.2d 739, 3rd Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Enrique Diaz, 535 F.2d 130, 1st Cir. (1976)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Enrique Diaz, 535 F.2d 130, 1st Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John T. Dirring v. United States, 370 F.2d 862, 1st Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesJohn T. Dirring v. United States, 370 F.2d 862, 1st Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Merle R. Whitaker, 722 F.2d 1533, 11th Cir. (1984)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Merle R. Whitaker, 722 F.2d 1533, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kafes, 214 F.2d 887, 3rd Cir. (1954)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Kafes, 214 F.2d 887, 3rd Cir. (1954)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Richard J. Hilliard v. United States, 345 F.2d 252, 10th Cir. (1965)Document6 pagesRichard J. Hilliard v. United States, 345 F.2d 252, 10th Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nathan Richman, Administrator v. General Motors Corporation, 437 F.2d 196, 1st Cir. (1971)Document6 pagesNathan Richman, Administrator v. General Motors Corporation, 437 F.2d 196, 1st Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Frank Sacco, 571 F.2d 791, 4th Cir. (1978)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Frank Sacco, 571 F.2d 791, 4th Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John Ferguson, Jr. v. George H. Eakle John Ferguson, Jr. Lois Kittredge, 492 F.2d 26, 3rd Cir. (1974)Document7 pagesJohn Ferguson, Jr. v. George H. Eakle John Ferguson, Jr. Lois Kittredge, 492 F.2d 26, 3rd Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ottens, 74 F.3d 357, 1st Cir. (1996)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Ottens, 74 F.3d 357, 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Andrew N. Farnese v. Alberto M. Bagnasco and Laila Covre, A.K.A. Laila Bagnasco. Appeal of Alberto M. Bagnasco, 687 F.2d 761, 3rd Cir. (1982)Document9 pagesAndrew N. Farnese v. Alberto M. Bagnasco and Laila Covre, A.K.A. Laila Bagnasco. Appeal of Alberto M. Bagnasco, 687 F.2d 761, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dunstan Wellington Burnett, 671 F.2d 709, 2d Cir. (1982)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Dunstan Wellington Burnett, 671 F.2d 709, 2d Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Roman Torino v. Texaco, Inc, 378 F.2d 268, 3rd Cir. (1967)Document3 pagesRoman Torino v. Texaco, Inc, 378 F.2d 268, 3rd Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Anthony Dennis Ramos, 413 F.2d 743, 1st Cir. (1969)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Anthony Dennis Ramos, 413 F.2d 743, 1st Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lockaby v. Young, 10th Cir. (2002)Document11 pagesLockaby v. Young, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Mala, 7 F.3d 1058, 1st Cir. (1993)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Mala, 7 F.3d 1058, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roland Lorenzo Mitchell, 464 F.3d 1149, 10th Cir. (2006)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Roland Lorenzo Mitchell, 464 F.3d 1149, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. David Fields, 39 F.3d 439, 3rd Cir. (1994)Document13 pagesUnited States v. David Fields, 39 F.3d 439, 3rd Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Edward Krock v. Electric Motor & Repair Company, Inc., 339 F.2d 73, 1st Cir. (1964)Document4 pagesEdward Krock v. Electric Motor & Repair Company, Inc., 339 F.2d 73, 1st Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Herbert G. Miller II, 869 F.2d 1418, 10th Cir. (1989)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Herbert G. Miller II, 869 F.2d 1418, 10th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- George C. Desmond v. United States of America, (Two Cases), 333 F.2d 378, 1st Cir. (1964)Document6 pagesGeorge C. Desmond v. United States of America, (Two Cases), 333 F.2d 378, 1st Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez-Mateo v. Fuentes-Agostini, 1st Cir. (2003)Document6 pagesRodriguez-Mateo v. Fuentes-Agostini, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Charles A. Meeker v. Carl A. Rizley, R. L. Minton, Lee H. Bullard, J. M. Burden, and v. P. McClain, 324 F.2d 269, 10th Cir. (1963)Document4 pagesCharles A. Meeker v. Carl A. Rizley, R. L. Minton, Lee H. Bullard, J. M. Burden, and v. P. McClain, 324 F.2d 269, 10th Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Torres-Vargas v. Pereira, 431 F.3d 389, 1st Cir. (2005)Document6 pagesTorres-Vargas v. Pereira, 431 F.3d 389, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument7 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ronald Sine Larry Danner v. Local No. 992 International Brotherhood of Teamsters Eastern Conference of Teamsters Mitchell Transport, Inc., 882 F.2d 913, 4th Cir. (1989)Document5 pagesRonald Sine Larry Danner v. Local No. 992 International Brotherhood of Teamsters Eastern Conference of Teamsters Mitchell Transport, Inc., 882 F.2d 913, 4th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument12 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Albert N. Dukow, Appeal of Thomas S. Crow. Appeal of Saul Brourman, 453 F.2d 1328, 3rd Cir. (1972)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Albert N. Dukow, Appeal of Thomas S. Crow. Appeal of Saul Brourman, 453 F.2d 1328, 3rd Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Warren v. City of Lynn, 21 F.3d 420, 1st Cir. (1994)Document6 pagesWarren v. City of Lynn, 21 F.3d 420, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eduardo Zavala Santiago v. Alfredo Gonzalez Rivera, 553 F.2d 710, 1st Cir. (1977)Document5 pagesEduardo Zavala Santiago v. Alfredo Gonzalez Rivera, 553 F.2d 710, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hilti, Inc. v. John Oldach, 392 F.2d 368, 1st Cir. (1968)Document7 pagesHilti, Inc. v. John Oldach, 392 F.2d 368, 1st Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Stouffer v. Stifel Nicolaus & Co, 10th Cir. (1999)Document6 pagesStouffer v. Stifel Nicolaus & Co, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Peter J. Porcaro v. United States, 832 F.2d 208, 1st Cir. (1987)Document8 pagesPeter J. Porcaro v. United States, 832 F.2d 208, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Foodtown of Oyster Bay, Inc. v. Dilbert's Leasing and Development Corporation Debtor-Appellee, 334 F.2d 768, 2d Cir. (1964)Document3 pagesFoodtown of Oyster Bay, Inc. v. Dilbert's Leasing and Development Corporation Debtor-Appellee, 334 F.2d 768, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gary Stewart Buckley v. United States, 382 F.2d 611, 10th Cir. (1967)Document5 pagesGary Stewart Buckley v. United States, 382 F.2d 611, 10th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Leo J. Schlinsky v. United States, 379 F.2d 735, 1st Cir. (1967)Document7 pagesLeo J. Schlinsky v. United States, 379 F.2d 735, 1st Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Anthony M. Siragusa, 450 F.2d 592, 2d Cir. (1971)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Anthony M. Siragusa, 450 F.2d 592, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Syracuse Broadcasting Corporation v. Samuel I. Newhouse, The Herald Company, The Post-Standard Company and Central New York Broadcasting Corporation, 271 F.2d 910, 2d Cir. (1959)Document8 pagesSyracuse Broadcasting Corporation v. Samuel I. Newhouse, The Herald Company, The Post-Standard Company and Central New York Broadcasting Corporation, 271 F.2d 910, 2d Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Killion, 10th Cir. (1997)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Killion, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Donald Birkholz, SR., Donald Birkholz, JR., 19 F.3d 34, 10th Cir. (1994)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Donald Birkholz, SR., Donald Birkholz, JR., 19 F.3d 34, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Benjamin S. Sacharow v. Irving Vogel, 428 F.2d 1389, 2d Cir. (1970)Document5 pagesBenjamin S. Sacharow v. Irving Vogel, 428 F.2d 1389, 2d Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Al Phillips, 775 F.2d 1454, 11th Cir. (1985)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Al Phillips, 775 F.2d 1454, 11th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Davis v. Gibson, 10th Cir. (2002)Document6 pagesDavis v. Gibson, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 30 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 936, 30 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 33,246 Titus, Thomas E. v. Mercedes Benz of North America, 695 F.2d 746, 3rd Cir. (1982)Document30 pages30 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 936, 30 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 33,246 Titus, Thomas E. v. Mercedes Benz of North America, 695 F.2d 746, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- E. David Gable v. Dean Witter Reynolds, 4th Cir. (1998)Document12 pagesE. David Gable v. Dean Witter Reynolds, 4th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument18 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James P. Pasquale v. Robert H. Finch, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 418 F.2d 627, 1st Cir. (1969)Document7 pagesJames P. Pasquale v. Robert H. Finch, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 418 F.2d 627, 1st Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Michael J. Burke v. Gateway Clipper, Inc, 441 F.2d 946, 3rd Cir. (1971)Document6 pagesMichael J. Burke v. Gateway Clipper, Inc, 441 F.2d 946, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Pigott, James P., T/d/b/a James P. Pigott Building Materials. Appeal of Conestoga Ceramic Tile Distributors, Inc, 684 F.2d 239, 3rd Cir. (1982)Document9 pagesIn Re Pigott, James P., T/d/b/a James P. Pigott Building Materials. Appeal of Conestoga Ceramic Tile Distributors, Inc, 684 F.2d 239, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. HubbardFrom EverandU.S. v. HubbardNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corpus Et Al. vs. PamularDocument4 pagesCorpus Et Al. vs. PamularLincy Jane AgustinNo ratings yet

- Land Titles and Deeds Subject Law SchoolDocument10 pagesLand Titles and Deeds Subject Law SchoolEllen Glae Daquipil100% (1)

- Mcle NotesDocument15 pagesMcle NotesJay-Ar C. GalidoNo ratings yet

- The Code of Civil Procedure 1908Document717 pagesThe Code of Civil Procedure 1908alkca_lawyerNo ratings yet

- Santulan v. Executive SecretaryDocument18 pagesSantulan v. Executive SecretaryCharmaineJoyceR.MunarNo ratings yet

- Adkins v. Panish Et Al - Document No. 3Document7 pagesAdkins v. Panish Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Maneka Gandhi Vs Union of IndiaDocument2 pagesManeka Gandhi Vs Union of IndiaRathin BanerjeeNo ratings yet

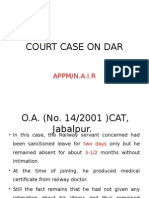

- Court Case On Dar AppmDocument63 pagesCourt Case On Dar AppmIndian Railways Knowledge PortalNo ratings yet

- 2007 CivillawbarqsandanswersDocument13 pages2007 CivillawbarqsandanswersLou Corina LacambraNo ratings yet

- GD RespondentsDocument21 pagesGD RespondentsAnonymous 37U1VpENo ratings yet

- People Vs SalanguitDocument23 pagesPeople Vs SalanguitKirsten Denise B. Habawel-VegaNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs CaDocument4 pagesRepublic Vs CaLizzette GuiuntabNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 195670 December 3, 2012 WILLEM BEUMER, Petitioner, AVELINA AMORES, RespondentDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 195670 December 3, 2012 WILLEM BEUMER, Petitioner, AVELINA AMORES, RespondentAnonymous wINMQaNNo ratings yet

- Metrobank Ordered to Release P15M Deposit in G&P Builders Rehabilitation CaseDocument24 pagesMetrobank Ordered to Release P15M Deposit in G&P Builders Rehabilitation CaseAndrea De JesusNo ratings yet

- HTJ Sentencing MemoDocument62 pagesHTJ Sentencing MemozmtillmanNo ratings yet

- Initial BriefDocument57 pagesInitial BriefmikebvaldesNo ratings yet

- Maternally Yours, Inc. v. Your Maternity Shop, Inc., 234 F.2d 538, 2d Cir. (1956)Document11 pagesMaternally Yours, Inc. v. Your Maternity Shop, Inc., 234 F.2d 538, 2d Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hassan Kadir & Ors v. Mohamed Moidu Mohamed & Anor: CONTRACT: Sale and Purchase of Land - Specific PerformanceDocument16 pagesHassan Kadir & Ors v. Mohamed Moidu Mohamed & Anor: CONTRACT: Sale and Purchase of Land - Specific PerformanceFitri KhalisNo ratings yet