Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States Court of Appeals: Published

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States Court of Appeals: Published

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

In Re: JAMES OWEN MURPHY, JR.,

Debtor.

JAMES OWEN MURPHY, JR., d/b/a

Murphys Golf Shop,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

No. 05-1637

v.

GERALD M. ODONNELL, Trustee,

Defendant-Appellee.

In Re: STANLEY JOSEPH GORALSKI;

DORIS ANN GORALSKI,

Debtors.

GERALD M. ODONNELL, Chapter 13

Trustee,

Trustee-Appellant,

No. 05-1844

v.

STANLEY JOSEPH GORALSKI; DORIS

ANN GORALSKI,

Debtors-Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia, at Alexandria.

Claude M. Hilton, Senior District Judge.

(CA-05-151-1-CMH; BK-03-15596-SSM; CA-05-353-1;

BK-03-12055-SSM)

IN RE: MURPHY

Argued: November 28, 2006

Decided: January 18, 2007

Before WILLIAMS and TRAXLER, Circuit Judges, and

HAMILTON, Senior Circuit Judge.

Affirmed by published opinion. Senior Judge Hamilton wrote the

opinion, in which Judge Williams and Judge Traxler joined.

COUNSEL

Bennett Allan Brown, Fairfax, Virginia, for Appellant in No. 051637. Gerald M. ODonnell, Alexandria, Virginia, for Appellee in

No. 05-1637/Appellant in No. 05-1844. Timothy John McGary, Fairfax, Virginia, for Appellees in No. 05-1844.

OPINION

HAMILTON, Senior Circuit Judge:

The two cases before the court involve instances in which the

Chapter 13 trustee sought to modify a confirmed Chapter 13 plan to

increase the amount to be paid to the unsecured creditors.1 In the first

case, that of Stanley and Doris Goralski, the Chapter 13 trustee sought

to modify the confirmed Chapter 13 plan after the bankruptcy court

granted the Goralskis permission to refinance the mortgage on their

residence. In the refinancing, the Goralskis received some of the

equity in their residence in cash in exchange for a corresponding

amount of debt, and the Chapter 13 trustee sought a portion of this

money for the further benefit of the unsecured creditors. The Goralskis sought to refinance their mortgage primarily because Stanley

1

The cases were argued seriatim, but we have consolidated them for

decision.

IN RE: MURPHY

Goralskis earned income was cut approximately in half, making it

difficult for the Goralskis to make their plan payments and, at the

same time, pay their ordinary and necessary living expenses. In the

second case, that of James Owen Murphy, Jr., the Chapter 13 trustee

sought to modify the confirmed Chapter 13 plan after the bankruptcy

court granted Murphy permission to sell his condominium. The Chapter 13 trustee sought a portion of the sale proceeds for the further benefit of the unsecured creditors because, without a modification,

Murphy stood to pocket in excess of $80,000, as his condominium

had dramatically increased in value post-confirmation. The bankruptcy court granted the motion to modify in Murphys case, but

denied it in the Goralskis case. See In re Murphy, 327 B.R. 760

(Bankr. E.D. Va. 2005). The district court affirmed the bankruptcy

courts decisions. Murphy appeals the decision in his case, as does the

Chapter 13 trustee in the Goralskis case. For the reasons stated

below, we affirm.

I

The facts and procedural history in these two cases are not in dispute and are set forth separately for the readers convenience.

A

Stanley and Doris Goralski filed a joint Chapter 13 petition in the

United States Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Virginia on

April 29, 2003. The schedules filed with the petition reflected that

they owned real property located at 13617 Chevy Chase Lane, Chantilly, Virginia, which they valued at $223,000. The schedules further

reflected that the property was subject to liens in the total amount of

$192,400. The Goralskis listed the sum of $89,438 as the amount of

their unsecured debt. The plan filed by the Goralskis with their petition was confirmed without objection on September 18, 2003. It

required the Goralskis to pay the Chapter 13 trustee $1,100 per month

for thirty-six months and estimated a twenty-eight percent dividend

to the unsecured creditors. The Goralskis confirmed plan provided

that, upon confirmation, "[a]ll property of the estate shall revest in the

debtor[s]."

IN RE: MURPHY

On October 21, 2004, approximately eighteen months after the

Chapter 13 petition was filed, the Goralskis filed a motion for permission to refinance the mortgage on their residence, which had appreciated significantly in value. As part of the refinancing, the Goralskis

sought to obtain a portion of the equity in their residence in cash in

exchange for a corresponding amount of debt.2 The primary reason

given for seeking to refinance was that Stanley Goralskis earned

income had been cut approximately in half, making it difficult for the

Goralskis to make their plan payments and, at the same time, pay their

ordinary and necessary living expenses.3 In the motion, the Goralskis

offered to pay all remaining payments required under the confirmed

plan.

At the hearing on the motion, the Chapter 13 trustee took the position that, to the extent the proceeds of the refinancing were sufficient

to pay all filed claims in full, the Goralskis should be required to pay

the filed claims at a rate of 100 percent. The bankruptcy court overruled the Chapter 13 trustees objection and granted the motion to

refinance. The next day, the Chapter 13 trustee filed a motion to

reconsider, as well as a motion to modify the confirmed plan, asking

that the Goralskis confirmed plan be modified to require $64,365

from the refinancing be paid to the Chapter 13 trustee to allow for the

payment of all filed claims at a rate of 100 percent.

After the bankruptcy court refused to grant the Chapter 13 trustees

motion for modification and motion for reconsideration, the Chapter

13 trustee appealed. Following the district courts affirmance of the

bankruptcy courts decision, the Chapter 13 trustee appealed to this

court.

B

On December 15, 2003, Murphy filed a voluntary Chapter 13 petition in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia. On his schedules, he indicated that he owned a condomin2

The refinancing the Goralskis sought is commonly referred to as a

"cash-out" refinancing.

3

It also appears from the record that the interest rate on the new loan

sought by the Goralskis was lower than the rate on their existing loan.

IN RE: MURPHY

ium located at 10125 Oakton Terrace Road, Oakton, Virginia, which

he valued at $155,000, subject to a lien of $121,000. Murphys schedules also listed $52,374 of unsecured debt. Murphys plan, which was

confirmed on April 29, 2004, required him to pay the Chapter 13

trustee $700 per month for thirty-six months and projected a thirtyseven percent dividend to the unsecured creditors. Like the Goralskis

confirmed plan, Murphys confirmed plan provided that, upon confirmation, "[a]ll property of the estate shall revest in the debtor."

On November 8, 2004, Murphy filed a motion for authority to sell

his condominium for $235,000, explaining that he had obtained a new

job in Pennsylvania and needed to move.4 In the motion, Murphy

indicated that he was willing to tender a sum to the Chapter 13 trustee

sufficient "to complete the payment of debtors chapter 13 payments."

The Chapter 13 trustee did not object to the sale, but stated at the

hearing that he needed approximately $30,000 from the sale to pay

the filed unsecured claims in full. Murphy objected to paying the

Chapter 13 trustee anything more than the approximately $12,000 still

owed under the confirmed plan. The bankruptcy court preliminarily

ruled that the sale proceeds constituted income that had to be applied

to the plan and directed that $30,000 be turned over to the Chapter

13 trustee. Because Murphys counsel stated that he intended to

appeal the ruling, and so that there could be a final order to allow the

contract to go to settlement, the order entered by the bankruptcy court

simply approved the sale and stated that disposition of the $30,000

would be the subject of a further order. The bankruptcy courts ruling

allowed the Chapter 13 trustee to disburse up to $11,973 of the proceeds (the amount needed to complete the scheduled plan payments)

but required the Chapter 13 trustee to hold the balance of the $30,000

pending further order of the court.5 Although the ruling technically

favored the Chapter 13 trustee, the Chapter 13 trustee moved for

4

Murphys confirmed plan provided that he could not sell his condominium without bankruptcy court approval.

5

The exact details concerning the sale are not in the record. It appears

that, after paying the required plan payments, Murphy stood to net over

$80,000. Of this amount, the Chapter 13 trustee sought approximately

$18,000 to pay the unsecured creditors at a rate of 100 percent. Thus,

with the unsecured creditors being paid at a rate of 100 percent, Murphy

nets over $60,000.

IN RE: MURPHY

reconsideration and, contemporaneously, moved to modify the plan

payments to allow for payment of all pending unsecured claims at a

rate of 100 percent.

In its decision, the bankruptcy court modified the confirmed plan

to provide for full payment of the pending unsecured claims. On

appeal to the district court, the district court affirmed the bankruptcy

courts ruling. Murphy now appeals to this court.

II

In contrast to a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, which involves the liquidation of a debtors assets, a Chapter 13 bankruptcy allows the debtor

to keep his assets. In a typical Chapter 13 bankruptcy, the debtor submits for bankruptcy court approval a plan to pay the debtors creditors

his disposable income over a period of three years. 11 U.S.C.

1321, 1322, and 1325. In exchange for the debtors commitment

to part with all of his disposable income, the debtor is given a discharge of his remaining dischargeable debts if he successfully complies with the terms of the plan. In re Crawford, 324 F.3d 539, 541

(7th Cir. 2003). Although secured claims in a Chapter 13 bankruptcy

must be paid in full, unsecured creditors need not be paid in full, provided, among other things, the plan is proposed in good faith and the

present value of what the unsecured creditors receive under the plan

is at least as much as they would receive in a Chapter 7 liquidation.

11 U.S.C. 1325(a)(3), (a)(4).

Generally, there are two types of Chapter 13 plans. "Percentage"

plans designate what percentage each unsecured creditor will receive

without specifying an exact amount the debtor must pay into the plan.

In re Golek, 308 B.R. 332, 335 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 2004). In contrast,

"pot" plans set the exact amount the debtor must pay into the plan,

leaving in question the percentage each unsecured creditor will

receive until all claims are approved. Id. Both of the plans in this case

are pot plans.

A confirmed Chapter 13 plan is "a new and binding contract, sanctioned by the court, between the debtors and their pre-confirmation

creditor[s]." Matter of Penrod, 169 B.R. 910, 916 (Bankr. N.D. Ind.

1994); see also 11 U.S.C. 1327(a) ("The provisions of a confirmed

IN RE: MURPHY

plan bind the debtor and each creditor, whether or not the claim of

such creditor is provided for by the plan, and whether or not such

creditor has objected to, had accepted, or has rejected the plan."). Like

other contracts, a confirmed Chapter 13 plan is subject to modification. In re Arnold, 869 F.2d 240, 241 (4th Cir. 1989).

Under 1329 of the Bankruptcy Code,6 a confirmed plan may be

modified at "any time after confirmation of the plan but before the

completion of payments" at the request of the debtor, the Chapter 13

trustee, or an allowed unsecured creditor in order to, among other

things, "increase or reduce the amount of payments on claims of a

particular class provided for by the plan; [or to] extend or reduce the

time for such payments." 11 U.S.C. 1329(a), (a)(1), and (a)(2).7

Under 1329(b)(1), any post-confirmation modification must comply

with 1322(a) and (b),8 1323(c),9 and 1325(a)10 of the Bank6

Section 1329 of the Bankruptcy Code provides in relevant part:

(a) At any time after confirmation of the plan but before the

completion of payments under such plan, the plan may be modified, upon request of the debtor, the trustee, or the holder of an

allowed unsecured claim, to

(1) increase or reduce the amount of payments on claims

of a particular class provided for by the plan;

(2)

extend or reduce the time for such payments; [or]

(3) alter the amount of the distribution to a creditor whose

claim is provided for by the plan to the extent necessary to

take account of any payment of such claim other than under

the plan.

***

(b)(1) Sections 1322(a), 1322(b), and 1323(c) of this title and the

requirements of section 1325(a) of this title apply to any modification under subsection (a) of this section.

11 U.S.C. 1329.

7

We note that 1329(a) allows for slight plan modification in two

additional circumstances: (1) to alter the amount of the distribution to a

creditor who has received a payment outside of the confirmed plan; and

(2) to reduce the debtors plan payments due to a debtors need to purchase health insurance. 11 U.S.C. 1329(a)(3), (a)(4).

8

Section 1322(a) of the Bankruptcy Code sets forth the requirements

that must be met by a Chapter 13 plan in order to be approved by the

IN RE: MURPHY

ruptcy Code. Id. 1329(b)(1). Moreover, we review the bankruptcy

courts decision whether to grant or deny a motion to modify a confirmed plan for an abuse of discretion. In re Arnold, 869 F.2d at 244.

We have not set forth a thorough analysis on how a bankruptcy

court should analyze a motion for modification pursuant to

1329(a)(1) or (a)(2). In In re Arnold, after rejecting several arguments of the debtor, we held that the bankruptcy court did not abuse

its discretion by increasing the debtors monthly payment from $800

to $1,500. Id. at 244-45. In reaching this decision, we held that the

doctrine of res judicata prevents modification of a confirmed plan

pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or (a)(2) unless the party seeking modification demonstrates that the debtor experienced a "substantial" and "unanticipated" post-confirmation change in his financial condition. Id.

at 243. This doctrine, which is applied in this circuit per In re Arnold,

ensures that confirmation orders will be accorded the necessary

degree of finality, preventing parties from seeking to modify plans

when minor and anticipated changes in the debtors financial condition take place. See In re Butler, 174 B.R. 44, 47 (Bankr. M.D. N.C.

1994) ("As a matter of sound public policy, as well as appropriate

judicial economy, there is no reason why either a creditor or a debtor

should be permitted to relitigate issues which were decided in the

bankruptcy court. Section 1322(b) sets forth all permissible provisions

which can be included in a Chapter 13 plan.

9

Section 1323(c) provides that any "holder of a secured claim that has

accepted or rejected the plan is deemed to have accepted or rejected, as

the case may be, the plan as modified, unless the modification provides

for a change in the rights of such holder from what such rights were

under the plan before modification, and such holder changes such holders previous acceptance or rejection." 11 U.S.C. 1323(c).

10

Section 1325(a) of the Bankruptcy Code provides, in the pertinent

part, that a bankruptcy court shall confirm a plan if: (1) it complies with

all applicable provisions of the Bankruptcy Code; (2) it has been proposed in good faith and not by any means forbidden by law; (3) the value

of property to be distributed under the plan on account of all allowed

unsecured creditors is not less than what would be paid under a Chapter

7 liquidation; and (4) the debtor is able to comply with the terms of the

modified plan. 11 U.S.C. 1325(a)(1), (a)(3), (a)(4), and (a)(6).

IN RE: MURPHY

confirmation order or which were available at the time of confirmation but not raised by the parties. Absent this salutary policy, there is

no readily available brake on the filing of motions under 1329 by

creditors and debtors simply hoping to produce a more favorable plan

based on the same facts presented at the original confirmation hearing."); but see Barbosa v. Soloman, 235 F.3d 31, 38-41 (1st Cir.

2000) (rejecting doctrine of res judicata as inconsistent with the language of 1329); Matter of Witkowski, 16 F.3d 739, 744-46 (7th Cir.

1994) (same).

Although we did not define the term "substantial" in In re Arnold,

we held that an increase in the debtors salary from $80,000 per year

to $200,000 per year was a substantial change in the debtors financial

condition. 869 F.2d at 243. A change is unanticipated if the debtors

present financial condition could not have been reasonably anticipated

at the time the plan was confirmed. Id.

Because the doctrine of res judicata did not prevent modification

of the debtors confirmed plan in In re Arnold, we proceeded to discuss and reject the one argument the debtor had concerning the

requirements of 1329(b)(1)that he did not have the ability to pay

$1,500 per month under the modified plan. Id. at 243-44.

Simply stated, per In re Arnold, when a bankruptcy court is faced

with a motion for modification pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or (a)(2), the

bankruptcy court must first determine if the debtor experienced a substantial and unanticipated change in his post-confirmation financial

condition. This inquiry will inform the bankruptcy court on the question of whether the doctrine of res judicata prevents modification of

the confirmed plan. If the change in the debtors financial condition

was either insubstantial or anticipated, or both, the doctrine of res

judicata will prevent the modification of the confirmed plan. However, if the debtor experienced both a substantial and unanticipated

change in his post-confirmation financial condition, then the bankruptcy court can proceed to inquire whether the proposed modification is limited to the circumstances provided by 1329(a). If the

proposed modification meets one of the circumstances listed in

1329(a), then the bankruptcy court can turn to the question of

whether the proposed modification complies with 1329(b)(1).

10

IN RE: MURPHY

A

In the case of the Goralskis, we agree with the bankruptcy court

and the district court that, through the cash-out refinancing, the Goralskis did not experience a substantial change in their financial condition. The record reflects that, although the Goralskis residence

appreciated in value post-confirmation, Stanley Goralskis earned

income had been reduced by approximately one-half. To meet their

obligations under the confirmed plan, the Goralskis refinanced their

existing mortgage, taking a sizeable amount of the equity (over

$64,000) in their residence to allow them to continue to meet their

financial obligations under the confirmed plan (through a lump sum

payment or continued periodic payments) and to pay their every day

living expenses.

All the Goralskis did was to eliminate a portion of their equity in

the property for cash in exchange for a corresponding amount of debt.

Thus, even when one considers that the Goralskis residence appreciated in value post-confirmation,11 at most, they simply received a

large loan in place of a small one. By any stretch, a loan, regardless

of the size, is not income. The apparent increase in their balance sheet

was offset by the amount of the loan, resulting in virtually no change

to their financial condition. To be sure, although the Goralskis

obtained a lower interest rate on their new loan, this fact alone did not

substantially improve their financial condition, especially when one

considers the primary reason for the refinancingStanley Goralskis

reduced income. Under the doctrine of res judicata, there being no

substantial change to the Goralskis financial condition, the cash-out

refinancing cannot provide a basis for modifying the Goralskis confirmed plan pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or (a)(2).

We note that there is considerable disagreement in the courts concerning whether a debtors proposal for an early payoff through the

refinancing of a mortgage amounts to a motion for modification of a

confirmed plan, thus, requiring an inquiry into the requirements of

1329(b)(1) before the modification can be granted. See In re

11

At the time they filed their Chapter 13 petition, the Goralskis had

$30,600 in equity in their residence. At the time of the refinancing, they

had over $64,000 in such equity.

IN RE: MURPHY

11

Brumm, 344 B.R. 795, 799-801 (Bankr. N.D. W. Va. 2006) (discussing case law). Some courts have held that a debtors proposal of an

early payoff through refinancing amounts to a motion for plan modification. See, e.g., In re Keller, 329 B.R. 697, 699-700 (Bankr. E.D.

Cal. 2005); In re Drew, 325 B.R. 765, 772 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 2005).

These courts primarily reason that an early payoff through refinancing: (1) reduces the number and the time for making payments under

1329(a)(1) and (a)(2); (2) preempts the right of the Chapter 13

trustee and the unsecured creditors to propose a modified plan during

the remaining term of the confirmed plan should the circumstances

warrant such a modification; and (3) amounts to a realization of the

value of appreciation which is akin to selling property at a substantial

gain. In re Keller, 329 B.R. at 699-700; In re Drew, 325 B.R. at 772.

In contrast to these courts, several courts have held that a debtors

proposal of an early payoff through refinancing does not amount to

a motion for plan modification. See, e.g., In re Miller, 325 B.R. 539,

540 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 2005). These courts essentially reason that a

debtors proposal of an early payoff through refinancing does not

change the substance of the confirmed plan and actually increases the

economic worth of the plan to the creditors by paying them off early.

Id. at 542.

If we were to write on a clean slate, we would find ourselves struggling much like these other courts have struggled. However, we are

not writing on a clean slate. Under In re Arnold, a debtor must experience a substantial and unanticipated change in his post-confirmation

financial condition before his confirmed plan can be modified pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or (a)(2). A debtors proposal of an early payoff

through the refinancing of a mortgage simply does not alter the financial condition of the debtor and, therefore, cannot provide a basis for

the modification of a confirmed plan pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or

(a)(2).

We also observe that our decision clearly strikes the right balance

between debtors on the one hand and creditors on the other. Our decision encourages refinancing when the debtor is struggling "under less

advantageous loan terms, which, by implication, puts the future

stream of payments to creditors under the Chapter 13 plan at risk." In

re Brumm, 344 B.R. at 803. As noted by the court in In re Brumm,

lower payments on long term debt, which often is achieved through

12

IN RE: MURPHY

lower interest rates on a refinancing, gives a debtor "greater short

term financial stability." Id. Moreover, our decision encourages refinancing when the debtors income, such as in the case of Stanley Goralski, goes down, thereby putting at risk the debtors ability to make

plan payments. The debtors early payoff coupled with his assumption

of long term debt works to the benefit of the unsecured creditors, as

the unsecured creditors receive their benefit of the bargain under the

confirmed plan and are no longer exposed to a further reduction in the

amount they will receive through a debtors motion to modify the

confirmed plan.

In this case, the Goralskis unquestionably took the more noble

course of seeking to fulfill their obligations under the confirmed plan

when the reduction in Stanley Goralskis income could have motivated them to file their own motion to modify, seeking to pay less.

For taking the high road, the Goralskis should not be penalized.

Accordingly, we affirm the district courts affirmance of the bankruptcy courts decision in the Goralskis case because the doctrine of

res judicata prevents modification of the Goralskis confirmed plan

pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or (a)(2).

B

Unlike the Goralskis case, in Murphys case, we conclude that

Murphy did experience a substantial and unanticipated change in his

post-confirmation financial condition, and, thus, the doctrine of res

judicata does not prevent the modification of Murphys confirmed

plan pursuant to 1329(a)(1) or (a)(2). To be sure, Murphy listed the

value of his condominium as of December 15, 2003, the date his

bankruptcy petition was filed, at $155,000, subject to a lien of

$121,000. In November 2004, he sold it for $235,000, a 51.6 percent

increase in only eleven months. Unquestionably, the money received

by Murphy on the sale of his condominium represents a "substantial"

improvement in Murphys financial condition. Unlike the Goralskis

refinancing, Murphy, by selling his condominium, received a substantial amount of readily available cash without any debt. Thus, his

financial condition substantially changed with the receipt of this

income, while the Goralskis condition did not improve in light of the

new debt they assumed.

IN RE: MURPHY

13

Turning to the question of whether this change in Murphys financial condition could have been reasonably anticipated at the time the

plan was confirmed, on the one hand, the Chapter 13 trustee should

have general knowledge of real estate market trends in his district. In

this case, the parties apparently concede that, in the two years preceding plan confirmation, the increase in the Housing Price Index for the

Washington, D.C.-Alexandria-Arlington area ranged from ten to thirteen percent per year. Thus, Murphys position would be stronger if

his house appreciated, say, twenty-five percent in eleven months.

However, a 51.6 percent increase certainly is an unanticipated change

given the current market trends. Accordingly, because there has been

a substantial and unanticipated change in Murphys financial condition, we can turn to the question of whether the bankruptcy court

abused its discretion when it ordered Murphy to share part of his newfound financial gains with his unsecured creditors.

In assessing whether to grant or deny the Chapter 13 trustees

motion for modification, the bankruptcy court was required to determine whether the Chapter 13 trustees motion for modification sought

one of the circumstances for modification set forth in 1329(a). The

Chapter 13 trustees motion meets this requirement, as he sought to,

among other things, increase the amount paid to the unsecured creditors. See 11 U.S.C. 1329(a)(1). Next, the bankruptcy court was

required to determine if the Chapter 13 trustees proposed modification complied with 1329(b)(1). As noted above, under 1329(b)(1),

any post-confirmation modification of a confirmed plan must comply

with 1322(a) and (b), 1323(c), and 1325(a) of the Bankruptcy

Code. Id. 1329(b)(1).

Sections 1322(a) and (b) set forth the mandatory and permissive

provisions of a Chapter 13 plan. The Chapter 13 trustees motion for

modification implicates 1322(a)(1) in the sense that the modification is seeking to ensure that a portion of Murphys new-found

income is paid to ensure the execution of the modified plan. Section

1323(c) provides that if a secured creditor has accepted a plan, it is

deemed to accept the modified plan unless the modified plan changes

the treatment of the secured creditors claim. The Chapter 13 trustees

motion does not implicate this section. Section 1325(a) contains the

standards for confirmation of a planincluding the "good faith" test

in (a)(3), the "best interests of creditors" test in (a)(4), and the

14

IN RE: MURPHY

"ability to pay" test in (a)(6). These sections are implicated in this

case.

First, it is obvious that the Chapter 13 trustees proposal to modify

the plan to pay the unsecured creditors at a rate of 100 percent is feasible insofar as Murphy unquestionably has the ability to pay the

unsecured creditors at a rate of 100 percent. Indeed, even with a 100

percent payout, Murphy still is netting in excess of $60,000 on the

sale of his condominium without any corresponding debt. Next, we

agree with the lower courts and the Chapter 13 trustee that a 100 percent payment to the creditors meets the best interest of the creditors

under the circumstances of this case. Finally, the Chapter 13 trustees

proposal to modify was made in good faith. Our decision in In re

Arnold recognizes that a debtor who experiences a substantial and

unanticipated improvement in his financial condition after confirmation should not be able to avoid paying more to his creditors. 869 F.2d

at 242. In contravention to In re Arnold, Murphy is seeking to do just

that. He is seeking to pocket over $80,000 by selling his residence

less than a year after his plan was confirmed, without paying a portion

of that money to his unsecured creditors, who are receiving under the

current confirmed plan only about thirty-seven cents on the dollar. In

exercising his fiduciary duty, the Chapter 13 trustee proposed the

modification in good faith to prevent Murphy from receiving such a

substantial windfall. Accordingly, the bankruptcy court did not abuse

its discretion when it modified Murphys confirmed plan to provide

for full payment of the pending unsecured claims.

C

Finally, we need to address one other argument raised by Murphy.

He argues that the bankruptcy court was not at liberty to modify his

confirmed plan because his plan, in accordance with 1327(b), vested

all property of the estate in him at the time of confirmation. According to Murphy, once his plan was confirmed, the Chapter 13 trustee

forfeited any claim to the proceeds of the sale.

Section 1327(b) of the Bankruptcy Code states that "the confirmation of a plan vests all of the property of the estate in the debtor." Id.

1327(b). Section 1327(c) states that such vesting "is free and clear

of any claim or interest of any creditor provided for by the plan." Id.

IN RE: MURPHY

15

1327(c). Section 1306(a) of the Bankruptcy Code, which defines the

concept "property of the estate" for purposes of Chapter 13, states:

(a) Property of the estate includes, in addition to the property specified in section 541 of this title

(1) all property of the kind specified in such section that the debtor acquires after the commencement of the case but before the case is closed,

dismissed, or converted to a case under chapter 7,

11, or 12 of this title, whichever occurs first; and

(2) earnings from services performed by the

debtor after the commencement of the case but

before the case is closed, dismissed, or converted

to a case under chapter 7, 11, or 12 of this title,

whichever occurs first.

Id. 1306(a). By providing that the bankruptcy estate continues to be

replenished by post-petition property until the case is closed, dismissed, or converted under Chapter 7, 11, or 12 of the Bankruptcy

Code, 1306(a) provides for the continued existence of the bankruptcy estate until the earliest of any of the above-mentioned events

occur.

Given the language of 1306(a) and 1327(b), it is understandable

that the interplay of these two sections of the Bankruptcy Code has

troubled courts and commentators. See, e.g., Barbosa, 235 F.3d at 3637; David B. Wheeler, Whose Property Is It Anyway?, 18-Nov Am.

Bankr. Inst. J. 14 (1999). Indeed, on the one hand, 1306(a) expands

the definition of property of the estate to all property obtained by the

debtor through the end of his case, but, on the other hand, 1327(b)

states that all property of the estate vests in the debtor upon confirmation of the plan.

Five interpretations of the interplay between 1306(a) and

1327(b) have developed. See Woodward v. Taco Bueno Rest., Inc.,

2006 WL 3542693 (N.D. Tex. December 8, 2006) (discussing four

interpretations and offering a fifth). To resolve Murphys argument,

16

IN RE: MURPHY

we need not discuss these varying interpretations or select one as the

most preferable. Under In re Arnold, a debtor cannot use plan confirmation as a license to shield himself from the reach of his creditors

when he experiences a substantial and unanticipated change in his

income. 869 F.2d at 241-43. To be sure, through 1329(a)(1) and

(a)(2), Congress gave a debtor an out when his financial condition

substantially deteriorates and, concomitantly, gave the Chapter 13

trustee and the unsecured creditors an avenue to recoup when the

debtors financial condition substantially improves, provided the

change in financial condition is unanticipated. In In re Arnold, we

permitted a modification of a confirmed plan where the debtors salary went from $80,000 to $200,000. Id. at 241. If a substantial, unanticipated salary increase warrants a modification, we see no reason

why substantial, unanticipated income realized from the sale of property would not also warrant a modification of a confirmed plan. Thus,

even though property vested in Murphy upon confirmation, this fact

did not prevent the Chapter 13 trustee from seeking to modify Murphys plan.

III

For the reasons stated herein, the judgments of the district court are

affirmed.

AFFIRMED

You might also like

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Carlisle, Brown & Carlisle, Attorneys at Law Petitioning v. Carolina Scenic Stages, in The Matter of Carolina Scenic Stages, Debtor, 242 F.2d 259, 4th Cir. (1957)Document5 pagesCarlisle, Brown & Carlisle, Attorneys at Law Petitioning v. Carolina Scenic Stages, in The Matter of Carolina Scenic Stages, Debtor, 242 F.2d 259, 4th Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Search Market v. Jubber, 10th Cir. (2012)Document70 pagesSearch Market v. Jubber, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- D C O A O T S O F: Grayrobinson, P.A. and Florida Insurance Guaranty Association, IncorporatedDocument5 pagesD C O A O T S O F: Grayrobinson, P.A. and Florida Insurance Guaranty Association, IncorporatedFloridaLegalBlogNo ratings yet

- Caplin v. Marine Midland Grace Trust Co., 406 U.S. 416 (1972)Document20 pagesCaplin v. Marine Midland Grace Trust Co., 406 U.S. 416 (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Suburban Mortgage v. Exel Properties, 4th Cir. (1999)Document11 pagesSuburban Mortgage v. Exel Properties, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PNB v. Sps NatividadDocument2 pagesPNB v. Sps NatividadJamMenesesNo ratings yet

- In Re: Jacqueline Albertine Huffman, Debtor. Jacqueline Albertine Huffman v. Maryland National Bank, 989 F.2d 493, 4th Cir. (1993)Document5 pagesIn Re: Jacqueline Albertine Huffman, Debtor. Jacqueline Albertine Huffman v. Maryland National Bank, 989 F.2d 493, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chisolm v. Transouth Financial, 4th Cir. (1996)Document14 pagesChisolm v. Transouth Financial, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re: Ben Franklin Hotel Associates, Debtor Ben Franklin Hotel Associates, 186 F.3d 301, 3rd Cir. (1999)Document14 pagesIn Re: Ben Franklin Hotel Associates, Debtor Ben Franklin Hotel Associates, 186 F.3d 301, 3rd Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Development Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of AppealsDocument11 pagesDevelopment Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of AppealsMalik BaltNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eighth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eighth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 175380 PDFDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 175380 PDFkyla_0111No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument22 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kawananokoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349 (1907)Document10 pagesKawananokoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349 (1907)Don VillegasNo ratings yet

- United States v. Michael G. Morgan, 51 F.3d 1105, 2d Cir. (1995)Document14 pagesUnited States v. Michael G. Morgan, 51 F.3d 1105, 2d Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Draft Dispossessory Appeal OptionsDocument12 pagesDraft Dispossessory Appeal Optionswekesamadzimoyo1No ratings yet

- Helvering v. Southwest Consolidated Corp., 315 U.S. 194 (1942)Document6 pagesHelvering v. Southwest Consolidated Corp., 315 U.S. 194 (1942)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rusch v. John Duncan Land & Mining Co., 211 U.S. 526 (1909)Document3 pagesRusch v. John Duncan Land & Mining Co., 211 U.S. 526 (1909)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument8 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Baldwin, 593 F.3d 1155, 10th Cir. (2010)Document15 pagesIn Re Baldwin, 593 F.3d 1155, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. James Carfora, 489 F.2d 354, 2d Cir. (1973)Document7 pagesUnited States v. James Carfora, 489 F.2d 354, 2d Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- DBP v. Court of Appeals G.R. 110053Document5 pagesDBP v. Court of Appeals G.R. 110053jackNo ratings yet

- Special Proceeding Case DigestDocument4 pagesSpecial Proceeding Case DigestQuinnee Vallejos100% (2)

- In Re: Lan Associates Xi, L.P. Patricia A. Staiano, United States Trustee v. James J. Cain, Trustee For Lan Associates Xi, L.P., AppellantDocument20 pagesIn Re: Lan Associates Xi, L.P. Patricia A. Staiano, United States Trustee v. James J. Cain, Trustee For Lan Associates Xi, L.P., AppellantScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re International Match Corp. Ehrhorn v. International Match Realization Co., Limited, 190 F.2d 458, 2d Cir. (1951)Document21 pagesIn Re International Match Corp. Ehrhorn v. International Match Realization Co., Limited, 190 F.2d 458, 2d Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument22 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Three Sisters v. Harden, 4th Cir. (1999)Document15 pagesThree Sisters v. Harden, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rallos V Felix Go Chan & Realty CoprDocument15 pagesRallos V Felix Go Chan & Realty CoprDarwin SolanoyNo ratings yet

- Alipio vs. Court of Appeals PDFDocument10 pagesAlipio vs. Court of Appeals PDFShairaCamilleGarciaNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument5 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Mitchell, C.A.A.F. (1999)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Mitchell, C.A.A.F. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fifth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brandt & Brandt Printers, Inc. v. David Charles Klein, Trustee in Bankruptcy of William Friedman, Doing Business Under The Name and Style of Faultless Press, 220 F.2d 935, 2d Cir. (1955)Document4 pagesBrandt & Brandt Printers, Inc. v. David Charles Klein, Trustee in Bankruptcy of William Friedman, Doing Business Under The Name and Style of Faultless Press, 220 F.2d 935, 2d Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitDocument20 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitForeclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- Second Division (G.R. No. 129764. March 12, 2002 Geoffrey F. Griffith, Petitioner, V. Hon. Court of AppealsDocument9 pagesSecond Division (G.R. No. 129764. March 12, 2002 Geoffrey F. Griffith, Petitioner, V. Hon. Court of AppealsKat AtienzaNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Forgee Metal Products, Inc, 229 F.2d 799, 3rd Cir. (1956)Document5 pagesIn The Matter of Forgee Metal Products, Inc, 229 F.2d 799, 3rd Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Carl Michael Caranna, Debtor. Carol Ruth Huserik v. Carl Michael Caranna, 963 F.2d 382, 10th Cir. (1992)Document4 pagesIn Re Carl Michael Caranna, Debtor. Carol Ruth Huserik v. Carl Michael Caranna, 963 F.2d 382, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joaquin Castañer, Debtor v. Rafael Mora, Creditor, 234 F.2d 710, 1st Cir. (1956)Document7 pagesJoaquin Castañer, Debtor v. Rafael Mora, Creditor, 234 F.2d 710, 1st Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Development Bank of The Phils vs. CADocument4 pagesDevelopment Bank of The Phils vs. CADetty AbanillaNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Farmer v. Banco Popular of North America, 10th Cir. (2014)Document15 pagesFarmer v. Banco Popular of North America, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re: O'Brien Environmental Energy, Inc., Debtor Calpine Corporation v. O'Brien Environmental Energy, Inc., Now Known As NRG Generating (U.s.), Inc, 181 F.3d 527, 3rd Cir. (1999)Document15 pagesIn Re: O'Brien Environmental Energy, Inc., Debtor Calpine Corporation v. O'Brien Environmental Energy, Inc., Now Known As NRG Generating (U.s.), Inc, 181 F.3d 527, 3rd Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gallent VsDocument13 pagesGallent Vsmiamor1022No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument11 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dio Vs Japor: 154129: July 8, 2005: J. Quisumbing: First Division: DecisionDocument6 pagesDio Vs Japor: 154129: July 8, 2005: J. Quisumbing: First Division: DecisionAlyssa MateoNo ratings yet

- Rivera-Pascual V LimDocument3 pagesRivera-Pascual V LimRose De JesusNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Debtors (Rebecca Fleury's) Response To Motion To Dismiss-Fleury Chapter 7 BankruptcyDocument4 pagesDebtors (Rebecca Fleury's) Response To Motion To Dismiss-Fleury Chapter 7 Bankruptcyarsmith718No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kelly 0Document17 pagesKelly 0washlawdailyNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 03 Denny Ermawan OkDocument62 pages03 Denny Ermawan OkAbdul ManafNo ratings yet

- Calculating partnership profits and capital balancesDocument1 pageCalculating partnership profits and capital balancesDe Nev Oel0% (1)

- TestDocument14 pagesTesthonest0988No ratings yet

- MFD Exam 500 QusDocument40 pagesMFD Exam 500 QusArvindKumarNo ratings yet

- Valuation Report DCF Power CompanyDocument34 pagesValuation Report DCF Power CompanySid EliNo ratings yet

- EBRDDocument17 pagesEBRDDana Cristina VerdesNo ratings yet

- Differences Between An Executor, Administrator and Special AdministratorDocument3 pagesDifferences Between An Executor, Administrator and Special AdministratorALee BudNo ratings yet

- VOLUME 4 BUSINESS VALUATION ISSUE 2: TRAPPED-IN CAPITAL GAINS REVISITEDDocument28 pagesVOLUME 4 BUSINESS VALUATION ISSUE 2: TRAPPED-IN CAPITAL GAINS REVISITEDgioro_miNo ratings yet

- Rent Agreement SummaryDocument2 pagesRent Agreement SummaryJohn FernendiceNo ratings yet

- Mean Vs Median Vs ModeDocument12 pagesMean Vs Median Vs ModekomalmongaNo ratings yet

- Mr. Mir Ashraf Ali ROLL NO: 2281-14-672-077: "Demat Account"Document103 pagesMr. Mir Ashraf Ali ROLL NO: 2281-14-672-077: "Demat Account"ahmedNo ratings yet

- 72825cajournal Feb2023 22Document4 pages72825cajournal Feb2023 22S M SHEKARNo ratings yet

- Lecture Slides - Chapter 9 & 10Document103 pagesLecture Slides - Chapter 9 & 10Phan Đỗ QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- BDA Advises Quasar Medical On Sale of Majority Stake To LongreachDocument3 pagesBDA Advises Quasar Medical On Sale of Majority Stake To LongreachPR.comNo ratings yet

- An Automated Teller Machine (ATM) Is A Computerized Telecommunications Device That EnablesDocument2 pagesAn Automated Teller Machine (ATM) Is A Computerized Telecommunications Device That EnablesParvesh GeerishNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Chavez - 027 050Document24 pagesNegotiable Instruments Chavez - 027 050JM LinaugoNo ratings yet

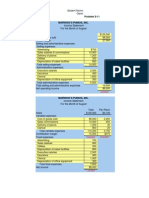

- Manage Accounts Receivable and InventoryDocument61 pagesManage Accounts Receivable and InventoryElisabeth LoanaNo ratings yet

- LMT MercDocument128 pagesLMT MercCj GarciaNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Valuation FINAL RevisedDocument45 pagesEnterprise Valuation FINAL Revisedchandro2007No ratings yet

- Itr 2 in Excel Format With Formula For A.Y. 2010 11Document12 pagesItr 2 in Excel Format With Formula For A.Y. 2010 11Shakeel sheoranNo ratings yet

- List of Uae Insurance CompaniesDocument9 pagesList of Uae Insurance CompaniesFawad IqbalNo ratings yet

- DBP v. Arcilla Ruling on Loan Disclosure ComplianceDocument3 pagesDBP v. Arcilla Ruling on Loan Disclosure ComplianceKarenliambrycejego RagragioNo ratings yet

- Forensic Auditor’s Report on Fabricated Expenditures by ABC Electricity BoardDocument7 pagesForensic Auditor’s Report on Fabricated Expenditures by ABC Electricity BoardChaitanya DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- SesesesesemmmmmemememememeDocument1 pageSesesesesemmmmmemememememeNorr MannNo ratings yet

- Ily Abella Surveyors Income StatementDocument6 pagesIly Abella Surveyors Income StatementJoy Santos33% (3)

- Tradewell Company ProfileDocument11 pagesTradewell Company ProfilePochender vajrojNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Interest Rates and Security ValuationDocument40 pagesChapter Three: Interest Rates and Security ValuationOwncoebdiefNo ratings yet

- (P3,300,000.00), Philippine Currency, Payable As FollowsDocument3 pages(P3,300,000.00), Philippine Currency, Payable As FollowsMPat EBarr0% (1)

- Case 10.1Document13 pagesCase 10.1Chin Figura100% (1)

- Elliot Advisors 2020 Q1 LetterDocument10 pagesElliot Advisors 2020 Q1 LetterEdwin UcheNo ratings yet