Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Moffitt v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO., LLC, 604 F.3d 156, 4th Cir. (2010)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Moffitt v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO., LLC, 604 F.3d 156, 4th Cir. (2010)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

JUDITH J. MOFFITT,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

RESIDENTIAL FUNDING COMPANY,

LLC; JP MORGAN CHASE BANK,

N.A.,

Defendants-Appellees.

LYNN A. FULMORE,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

PREMIER FINANCIAL CORPORATION,

on behalf of Maximus Financial

Corporation; SOVEREIGN BANK, a

U.S. Savings Bank,

Defendants-Appellees.

No. 10-1316

No. 10-1319

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

EDWIN RUBLE,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

THE MORTGAGE CONSULTANTS

INCORPORATED, a Maryland

Corporation; BANC ONE FINANCIAL

SERVICES, INCORPORATED,

Defendants-Appellees.

No. 10-1321

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the District of Maryland, at Baltimore.

J. Frederick Motz, District Judge.

(1:09-cv-02029-JFM; 1:09-cv-02028-JFM;

1:09-cv-02056-JFM)

Argued: March 26, 2010

Decided: May 3, 2010

Before WILKINSON, NIEMEYER, and SHEDD,

Circuit Judges.

Affirmed by published opinion. Judge Wilkinson wrote the

opinion, in which Judge Niemeyer and Judge Shedd joined.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Edwin David Hoskins, THE LAW OFFICES OF

E. DAVID HOSKINS, LLC, Baltimore, Maryland, for Appellants. James Christopher Martin, REED SMITH, LLP, Pitts-

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

burgh, Pennsylvania, for Appellees. ON BRIEF: Thomas L.

Allen, John M. McIntyre, David J. de Jesus, REED SMITH

LLP, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Gerard J. Gaeng, ROSENBERG, MARTIN, GREENBERG, LLP, Baltimore, Maryland, for Appellees Residential Funding Company, LLC, and

Sovereign Bank; LeAnn Pedersen Pope, Victoria R. Collado,

Andrew D. LeMar, BURKE, WARREN, MACKAY & SERRITELLA, PC, Chicago, Illinois, for Appellees JP Morgan

Chase Bank, N.A., and Banc One Financial Services, Incorporated; Philip M. Andrews, Katrina J. Dennis, KRAMON &

GRAHAM, P.A., Baltimore, Maryland, for Appellee Premier

Financial Corporation; Alexander Y. Thomas, Richard D.

Holzheimer, REED SMITH LLP, Falls Church, Virginia,

Andrew C. Bernasconi, REED SMITH LLP, Washington,

D.C., for Appellee Banc One Financial Services, Incorporated.

OPINION

WILKINSON, Circuit Judge:

In these three interlocutory appeals, the plaintiffs challenge

the district courts denial of their motions to remand their

cases to state court. While the procedural history of these

cases is involved, the legal issue is straightforward. After their

cases were removed and prior to moving to remand, the plaintiffs filed amended complaints in federal court that alleged

facts giving rise to federal diversity jurisdiction under the

Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 ("CAFA"), Pub. L. No.

109-2, 119 Stat. 4 (codified in scattered sections of 28

U.S.C.). Given these circumstances, we need not decide

whether the cases were improperly removed. Even assuming

that they were, we conclude that the amended complaints provided an independent basis for the district court to retain jurisdiction.

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

I.

The relevant facts in these three cases are as follows. In

2003, Judith Moffitt, Lynn Fulmore, and Edwin Ruble (collectively, "plaintiffs") each filed individual complaints in

Maryland trial court alleging violations of the Maryland Secondary Mortgage Loan Law against various financial entities

(collectively, "defendants"). In 2006, the trial court dismissed

plaintiffs claims on the ground that they were barred by the

statute of limitations. But in 2009, the Maryland Court of

Appeals reversed, permitting the cases to go forward. Master

Fin., Inc. v. Crowder, 972 A.2d 864 (Md. 2009).

Following this decision, plaintiffs counsel sent defendants

counsel a letter stating that plaintiffs intended to amend their

individual complaints into class actions. Enclosed with the

letter were draft copies of three amended class action complaints. According to these complaints, each putative class

consisted of "thousands of members." While the draft complaints did not specify the amounts in controversy, the letter

estimated that "the value of an individual claim will likely

range from $20,000 to $90,000."

Upon receiving these documents, defendants believed that

plaintiffs were alleging facts giving rise to federal diversity

jurisdiction under CAFA. See 28 U.S.C. 1332(d). They further believed that the draft complaints qualified as "other

paper[s]" under 28 U.S.C. 1446(b), which provides that a

defendant may remove a case that was not initially removable

within thirty days of receiving "a copy of an amended pleading, motion, order or other paper from which it may first be

ascertained that the case is one which is or has become

removable." Fearing that the thirty-day deadline would expire

before plaintiffs actually filed the amended complaints, defendants went ahead and removed the cases to the United States

District Court for the District of Maryland.

After removal, plaintiffs filed final versions of their

amended class action complaints in the federal court. As

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

plaintiffs acknowledge, these complaints satisfied the requirements for federal diversity jurisdiction under CAFA. 28

U.S.C. 1332(d). Each complaint named at least one defendant who was diverse in citizenship from at least one plaintiff,

1332(d)(2)(A); sought aggregate damages in excess of

$5,000,000, exclusive of interests and costs, 1332(d)(2), (6);

and alleged that there were at least one hundred class members, 1332(d)(5)(B). After plaintiffs filed these complaints,

defendants filed motions for leave to amend their original

notices of removal in order to base removal on plaintiffs

actual filing of the complaints.

A few weeks after filing their amended class action complaints, plaintiffs moved to remand the cases to state court. In

their view, neither the letter nor the enclosed draft complaints

that they sent to defendants qualified as "other paper[s]"

within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. 1446(b). Thus, they

argued, defendants had jumped the gun by removing the cases

before plaintiffs had actually filed the amended complaints.

Without deciding whether removal had been improper, the

district court denied plaintiffs motions for remand. Moffitt v.

Balt. Am. Mortgage, 665 F. Supp. 2d 515 (D. Md. 2009). It

reasoned that by filing amended class action complaints alleging "facts that clearly give rise to federal jurisdiction," plaintiffs had waived their rights to seek remand. Id. at 517. In its

view, this ruling was supported by "considerations of sound

policy." Id. Had plaintiffs filed their amended complaints in

state court, it explained, "defendants could then have filed

renewed notices of removal, eliminating the other paper

issue upon which plaintiff[s] current motions to remand are

based." Id. In the alternative, the district court granted defendants motions for leave to amend their notices of removal. Id.

at 517 n.2.

Following the district courts ruling, plaintiffs timely petitioned this court for permission to file interlocutory appeals

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

under 28 U.S.C. 1453(c)(1) of CAFA. We granted their

petitions on March 25, 2010.

II.

On appeal, plaintiffs principal argument is that the district

court was required to remand these cases because federal subject matter jurisdiction did not exist at the time of removal. In

their view, the district court should have given no consideration to the fact that they filed amended complaints prior to

moving to remand. We review de novo the district courts

denial of plaintiffs motions. Lontz v. Tharp, 413 F.3d 435,

439 (4th Cir. 2005).

The removal statute, 28 U.S.C. 1441(a), requires that a

case "be fit for federal adjudication at the time the removal

petition is filed." Caterpillar Inc. v. Lewis, 519 U.S. 61, 73

(1996). But the mere fact that a case does not meet this timing

requirement is not "fatal to federal-court adjudication" where

jurisdictional defects are subsequently cured. Id. at 64. Thus,

if a plaintiff voluntarily amends his complaint to allege a basis

for federal jurisdiction, a federal court may exercise jurisdiction even if the case was improperly removed. In Pegram v.

Herdrich, 530 U.S. 211 (2000), for instance, the Supreme

Court reasoned that because the plaintiff had amended her

complaint to add federal claims, "we therefore have jurisdiction regardless of the correctness of the removal." Id. at 215

n.2. Likewise, in Cades v. H & R Block, Inc., 43 F.3d 869 (4th

Cir. 1994), this court found no need to address the plaintiffs

argument that diversity jurisdiction was lacking at the time of

removal because the plaintiff had subsequently amended her

complaint to add claims which "firmly established" federal

jurisdiction. Id. at 873. As we explained, "an initial lack of the

right to removal may be cured when the final posture of the

case does not wrongfully extend federal jurisdiction." Id. (citing American Fire & Casualty Co. v. Finn, 341 U.S. 6, 16

(1951)).

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

Other circuits have reached similar conclusions. See, e.g.,

Barbara v. N.Y. Stock Exch., Inc., 99 F.3d 49, 56 (2d Cir.

1996) ("[I]f a district court erroneously exercises removal

jurisdiction over an action, and the plaintiff voluntarily

amends the complaint to allege federal claims, we will not

remand for want of jurisdiction."); Bernstein v. Lind-Waldock

& Co., 738 F.2d 179, 185 (7th Cir. 1984) ("[O]nce [the plaintiff] decided to take advantage of his involuntary presence in

federal court to add a federal claim to his complaint he was

bound to remain there.").

Turning to the facts here, we assume without deciding that

these cases were removed at a time when they did not satisfy

federal subject matter jurisdiction. But even if they were,

plaintiffs independently conferred jurisdiction on the district

court by filing their amended class action complaints prior to

moving to remand. As plaintiffs acknowledge and the district

court stated, these complaints alleged "facts that clearly give

rise to federal jurisdiction" under CAFA. Moffitt, 665 F. Supp.

2d at 517.

Plaintiffs contend, however, that this line of precedent,

which excuses jurisdictional defects at the time of removal

when they are later cured, does not apply here. In their view,

the cases above were concerned solely with preventing parties

from attacking final judgments on the basis of improper

removals and are therefore inapplicable where, as here, a case

is taken up on interlocutory appeal. We disagree. As we have

recognized, this line of precedent is grounded not only in the

interest of "finality" but also in larger considerations of "judicial economy." Able v. Upjohn Co., Inc., 829 F.2d 1330, 1334

(4th Cir. 1987), overruled on other grounds by Caterpillar,

519 U.S. at 74 n.11. In Caterpillar, for instance, the Court

emphasized that remanding the case after the jurisdictional

defect had been cured would "impose unnecessary and

wasteful burdens on the parties, judges, and other litigants."

519 U.S. at 76 (quoting Newman-Green, Inc. v. AlfonzoLarrain, 490 U.S. 826, 836 (1989)). While such concerns of

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

judicial economy are often implicated after a case reaches

final judgment, they are not confined to that situation. Requiring pointless movement between state and federal court

before a case is tried on the merits can likewise impose significant costs on both courts and litigants. We thus see no need

to abandon this line of precedent simply because this case

happens to be before us on interlocutory appeal.

Here, it would be a waste of judicial resources to remand

these cases on the basis of an antecedent violation of the

removal statute now that jurisdiction has been established.

Were we to do so, defendants would almost certainly remove

the cases back to federal court in light of plaintiffs amended

class action complaints. Plaintiffs have expressed no intent to

abandon their class action complaints, and defendants would

thus be able to file renewed notices of removal once the cases

landed back in state court.* Moreover, defendants would not

have to worry about the normal one-year limitation on removing diversity cases since it does not apply to class actions. See

28 U.S.C. 1453(b). Thus, these cases would likely end up in

federal court regardless of whether we ordered remands at this

juncture. Like the district court, we think that considerations

of judicial economy weigh against requiring such a pointless

exercise and in favor of allowing this case to go forward in

a federal forum where jurisdiction has been perfected.

Thus, we conclude that the district court did not err in

retaining jurisdiction after plaintiffs filed their amended class

action complaints. Having affirmed the district courts ruling

on this basis, we need not address plaintiffs argument that the

*Plaintiffs contest this point. In their view, the thirty-day deadline for

removal started when they filed their amended class action complaints in

federal court and thus has long since expired. We, however, find it illogical to contend that a case becomes removable to federal court when it is

already in federal court. Thus, we think it plain that these cases would not

become removable until after they were remanded to state court, assuming

of course that defendants initial removal was improper.

MOFFITT v. RESIDENTIAL FUNDING CO.

district court erred in granting defendants leave to amend their

initial notices of removal.

III.

Accordingly, the district courts order is

AFFIRMED.

You might also like

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- Lontz v. Tharp, 4th Cir. (2005)Document11 pagesLontz v. Tharp, 4th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 171177P PDFDocument6 pages171177P PDFRHTNo ratings yet

- Jimmy T. Bauknight v. Monroe County, Florida, 446 F.3d 1327, 11th Cir. (2006)Document7 pagesJimmy T. Bauknight v. Monroe County, Florida, 446 F.3d 1327, 11th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument10 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chris Horton and James E. Gardner v. Board of County Commissioners of Flagler County, Etc., 202 F.3d 1297, 11th Cir. (2000)Document9 pagesChris Horton and James E. Gardner v. Board of County Commissioners of Flagler County, Etc., 202 F.3d 1297, 11th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument7 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Murphy v. McKune, 10th Cir. (2005)Document7 pagesMurphy v. McKune, 10th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument50 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Grispino v. New England Mutual, 358 F.3d 16, 1st Cir. (2004)Document6 pagesGrispino v. New England Mutual, 358 F.3d 16, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Federal Quiet Title KansasDocument9 pagesFederal Quiet Title KansasJoniTay802No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument14 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Congress Credit Corporation v. Ajc International, Inc., 42 F.3d 686, 1st Cir. (1994)Document7 pagesCongress Credit Corporation v. Ajc International, Inc., 42 F.3d 686, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SC Dept. of Disabilities v. Hoover Universal, 535 F.3d 300, 4th Cir. (2008)Document13 pagesSC Dept. of Disabilities v. Hoover Universal, 535 F.3d 300, 4th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Patricia Boone, Patricia Boone Mandolyn Boyd Mary Jordan Mary McBride Arthaway McCullough Constance McFarland Eugene Paine Bernice Paine Mary Spratt Peggy Washington v. Citigroup, Inc. Citifinancial Inc. Associates First Capital Corporation Associates Corporation of North America Paul Spears D. Lavender Michelle Easter John Does 1-50 Citifinancial Corporation, 416 F.3d 382, 1st Cir. (2005)Document14 pagesPatricia Boone, Patricia Boone Mandolyn Boyd Mary Jordan Mary McBride Arthaway McCullough Constance McFarland Eugene Paine Bernice Paine Mary Spratt Peggy Washington v. Citigroup, Inc. Citifinancial Inc. Associates First Capital Corporation Associates Corporation of North America Paul Spears D. Lavender Michelle Easter John Does 1-50 Citifinancial Corporation, 416 F.3d 382, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument13 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ina Frankel Abramson, Irving Hellman and Beatrice Hellman v. Pennwood Investment Corp., and Edward Nathan, Intervenor-Appellant, 392 F.2d 759, 2d Cir. (1968)Document5 pagesIna Frankel Abramson, Irving Hellman and Beatrice Hellman v. Pennwood Investment Corp., and Edward Nathan, Intervenor-Appellant, 392 F.2d 759, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lovell v. Peoples Heritage, 14 F.3d 44, 1st Cir. (1994)Document4 pagesLovell v. Peoples Heritage, 14 F.3d 44, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Reply IPAFischerDocument8 pagesReply IPAFischerChrisNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 1161, Docket 79-2028Document9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 1161, Docket 79-2028Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Redondo-Borges v. Housing and Urban, 421 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2005)Document12 pagesRedondo-Borges v. Housing and Urban, 421 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Motion To DismissDocument15 pagesMotion To DismissCircuit MediaNo ratings yet

- Show TempDocument15 pagesShow TempJacob OglesNo ratings yet

- Hill v. Vanderbilt Capital Advisors, 10th Cir. (2012)Document14 pagesHill v. Vanderbilt Capital Advisors, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: For The Seventh CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: For The Seventh CircuitRHTNo ratings yet

- Maria Luisa Castro Lopez, Benita Ramos Acosta, Intervenors v. Jose E. Arraras, Etc., 606 F.2d 347, 1st Cir. (1979)Document11 pagesMaria Luisa Castro Lopez, Benita Ramos Acosta, Intervenors v. Jose E. Arraras, Etc., 606 F.2d 347, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Marks v. US Social Security, 4th Cir. (1996)Document6 pagesMarks v. US Social Security, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Maysonet-Robles v. Cabrero, 323 F.3d 43, 1st Cir. (2003)Document13 pagesMaysonet-Robles v. Cabrero, 323 F.3d 43, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Roberts v. United States, 10th Cir. (2000)Document6 pagesRoberts v. United States, 10th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PublishedDocument16 pagesPublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument14 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cruz v. Farquharson, 252 F.3d 530, 1st Cir. (2001)Document7 pagesCruz v. Farquharson, 252 F.3d 530, 1st Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northern Natural Gas Company v. Ralph Grounds, Malcolm Miller, Movant-Appellant v. Foulston, Siefkin, Powers & Eberhardt, 931 F.2d 678, 10th Cir. (1991)Document9 pagesNorthern Natural Gas Company v. Ralph Grounds, Malcolm Miller, Movant-Appellant v. Foulston, Siefkin, Powers & Eberhardt, 931 F.2d 678, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit: FiledDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit: FiledScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- VisendiDocument15 pagesVisendiwashlawdailyNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument11 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument14 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gibson v. State Farm Mutual, 10th Cir. (2006)Document17 pagesGibson v. State Farm Mutual, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Case: 15-14463 Date Filed: 08/10/2016 Page: 1 of 13Document13 pagesCase: 15-14463 Date Filed: 08/10/2016 Page: 1 of 13brianwtothNo ratings yet

- Iverson v. City of Boston, 452 F.3d 94, 1st Cir. (2006)Document13 pagesIverson v. City of Boston, 452 F.3d 94, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James Chongris and George Chongris v. Board of Appeals of The Town of Andover, 811 F.2d 36, 1st Cir. (1987)Document15 pagesJames Chongris and George Chongris v. Board of Appeals of The Town of Andover, 811 F.2d 36, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument10 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nicolas v. Perkins, 10th Cir. (2002)Document7 pagesNicolas v. Perkins, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitDocument21 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Westmoreland Capital Corporation, Joseph M. Jayson and Judith P. Jayson v. George D. Findlay and John F. Joyce, 100 F.3d 263, 2d Cir. (1996)Document11 pagesWestmoreland Capital Corporation, Joseph M. Jayson and Judith P. Jayson v. George D. Findlay and John F. Joyce, 100 F.3d 263, 2d Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument13 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument5 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument8 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Aponte-Torres v. Univ. of Puerto Rico, 445 F.3d 50, 1st Cir. (2006)Document10 pagesAponte-Torres v. Univ. of Puerto Rico, 445 F.3d 50, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument18 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Torromeo v. Town of Fremont, 438 F.3d 113, 1st Cir. (2006)Document7 pagesTorromeo v. Town of Fremont, 438 F.3d 113, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joan Dixon v. Ssa Baltimore Federal Credit Union, 991 F.2d 787, 4th Cir. (1993)Document4 pagesJoan Dixon v. Ssa Baltimore Federal Credit Union, 991 F.2d 787, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lyon v. Aguilar, 10th Cir. (2011)Document10 pagesLyon v. Aguilar, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sebastian V Bajar DigestDocument2 pagesSebastian V Bajar Digestjeffdelacruz100% (2)

- Sarsaba vs. Vda. de Te, 594 SCRA 410Document12 pagesSarsaba vs. Vda. de Te, 594 SCRA 410jdz1988No ratings yet

- Order XXXIII CPC Suits by Indigent Persons' PDFDocument4 pagesOrder XXXIII CPC Suits by Indigent Persons' PDFRahulNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: The Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Teofilo F. Manalo Law Office For Accused-AppellantDocument14 pagesSupreme Court: The Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Teofilo F. Manalo Law Office For Accused-AppellantKenneth Bryan Tegerero TegioNo ratings yet

- Ra 9344Document24 pagesRa 9344odycuaNo ratings yet

- Memorial On Behalf of PetitionerDocument35 pagesMemorial On Behalf of PetitionerAjitabhGoel67% (3)

- Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School BD., 396 U.S. 226 (1970)Document3 pagesCarter v. West Feliciana Parish School BD., 396 U.S. 226 (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Stealth Infra SDN V SR Alias Bin MarjohDocument2 pagesStealth Infra SDN V SR Alias Bin MarjohjacqNo ratings yet

- Kentucky's Foster Care System Is Improving, But Challenges Remain - 2006Document434 pagesKentucky's Foster Care System Is Improving, But Challenges Remain - 2006Rick ThomaNo ratings yet

- Alexandru Andrei Vicolas v. U.S. Attorney General, 11th Cir. (2015)Document15 pagesAlexandru Andrei Vicolas v. U.S. Attorney General, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

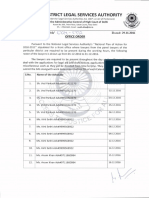

- Front Office Roster For The Month of December 2016Document2 pagesFront Office Roster For The Month of December 2016DLSA SOUTHNo ratings yet

- B.P. 22 SpaDocument2 pagesB.P. 22 SpaRaymond Bautista FusinganNo ratings yet

- LegalForms - (20) Motion To Post BailDocument3 pagesLegalForms - (20) Motion To Post BailIsidore Tarol IIINo ratings yet

- Complaint For Unlawful Detainer Group 1Document4 pagesComplaint For Unlawful Detainer Group 1Yuzuki EbaNo ratings yet

- De Leon V OngDocument7 pagesDe Leon V OngChino RazonNo ratings yet

- Sample Answer To Adversary Complaint in United States Bankruptcy CourtDocument3 pagesSample Answer To Adversary Complaint in United States Bankruptcy CourtStan Burman33% (6)

- United Vs Sebastian Until Heirs of Roxas Vs CADocument5 pagesUnited Vs Sebastian Until Heirs of Roxas Vs CAMariaAyraCelinaBatacanNo ratings yet

- Velarde v. Social Justice Society (GR No. 159357)Document2 pagesVelarde v. Social Justice Society (GR No. 159357)cycc100% (1)

- Personal Jurisdiction - Analysis and RulesDocument1 pagePersonal Jurisdiction - Analysis and RulesCharlena AumNo ratings yet

- Pre Trial Brief For ConcubinageDocument2 pagesPre Trial Brief For ConcubinageReshiel B. CCNo ratings yet

- Ram Das V N P V SIA Engineering Co LTD (2015Document25 pagesRam Das V N P V SIA Engineering Co LTD (2015Dylan ChongNo ratings yet

- Inspection of Public Records Compliance Guide 2015Document59 pagesInspection of Public Records Compliance Guide 2015sbroadweNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Conflict Cases CompilationDocument219 pagesCase Digest Conflict Cases CompilationMark LojeroNo ratings yet

- People Vs BaelloDocument21 pagesPeople Vs BaelloNico de la PazNo ratings yet

- Julius Stone PDFDocument24 pagesJulius Stone PDFNeeschey DixitNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument10 pagesTerm PaperMylene CanezoNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument54 pagesDownloadfilhodomeupaiNo ratings yet

- Consistency in The Chambers of The ECJ A Case Study On The Free Movement of GoodsDocument15 pagesConsistency in The Chambers of The ECJ A Case Study On The Free Movement of GoodsJack StevenNo ratings yet

- Meralco Vs CADocument8 pagesMeralco Vs CAdezNo ratings yet

- Two (2) Requisites For The Judicial Review of Administrative Decision/ActionsDocument1 pageTwo (2) Requisites For The Judicial Review of Administrative Decision/ActionsMei MeiNo ratings yet

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (558)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistFrom EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Summary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeFrom EverandSummary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryFrom EverandThe Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (881)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionFrom EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2475)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentFrom EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4125)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- Seven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your DreamsFrom EverandSeven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your DreamsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1549)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesFrom EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1635)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1458)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelFrom EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonFrom EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1479)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (233)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingFrom EverandWeapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (149)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessFrom EverandSummary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessNo ratings yet