Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Claude Brown Helen Brown v. City of Bristol, Tennessee Donald Brown, Deputy City Manager Frank Clifton, City Manager, 99 F.3d 1129, 4th Cir. (1996)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Claude Brown Helen Brown v. City of Bristol, Tennessee Donald Brown, Deputy City Manager Frank Clifton, City Manager, 99 F.3d 1129, 4th Cir. (1996)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

99 F.

3d 1129

NOTICE: Fourth Circuit Local Rule 36(c) states that citation

of unpublished dispositions is disfavored except for establishing

res judicata, estoppel, or the law of the case and requires

service of copies of cited unpublished dispositions of the Fourth

Circuit.

Claude BROWN; Helen Brown, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

CITY OF BRISTOL, TENNESSEE; Donald Brown, Deputy

City

Manager; Frank Clifton, City Manager, Defendants-Appellees.

No. 96-1057.

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.

Argued: September 26, 1996

Decided: October 31, 1996

ARGUED: Robert Tayloe Copeland, COPELAND, MOLINARY &

BIEGER, Abingdon, Virginia, for Appellants. James Earl Green, GREEN

& HALE, Bristol, Tennessee, for Appellees. ON BRIEF: Fred M.

Leonard, Bristol, Tennessee, for Appellants. Kenneth D. Hale, GREEN &

HALE, Bristol, Tennessee; M. Lacy West, Julia Cyphers West, WEST &

ROSE, Kingsport, Tennessee, for Appellees.

Before HALL, NIEMEYER, and HAMILTON, Circuit Judges.

OPINION

PER CURIAM:

Claude and Helen Brown are developers of a subdivision in Bristol, Tennessee,

for which they received a conditional approval from the City's Planning

Commission. The Planning Commission required that the Browns complete ten

items of street, water, and storm sewer work before the subdivision could "be

considered for final approval."

While there is no evidence that the Browns completed the conditions imposed

by Bristol, they nevertheless began selling lots to the public. When the City

learned of the sales, it published and recorded among the land records a notice

that the streets and other improvements in the subdivision "have not been

accepted or opened as, nor have the same otherwise received the legal status of,

public streets or improvements."

In response to the notice, the Browns filed this action in federal court against

the City of Bristol and two of its managerial employees, alleging that Bristol

had taken the Browns' property without due process of law, slandered the title

to their property, and inversely condemned the property. On the defendants'

motion to dismiss and for summary judgment, the district court entered

summary judgment dismissing the action. The court concluded that under

Tennessee law, the City of Bristol enjoyed state sovereign immunity and its

officers were qualifiedly immune under Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800,

815-19 (1982). This appeal followed.

The Browns contend on appeal principally that they did not have adequate

notice that the district court was going to treat the defendants' motion to dismiss

as one for summary judgment because the defendants labeled their motion as a

"motion to dismiss." The Browns also contend that the case should be

remanded on the takings issue because the district court did not address it and

that the district court erred in giving the City of Bristol immunity from Fifth

Amendment liability.

Having carefully reviewed the entire record in this case and considered the

arguments of counsel, we find no merit to the Browns' appeal.

On the Browns' claim that they were not notified that the defendants' motion to

dismiss would be treated by the court as a motion for summary judgment, the

record belies their contentions. In the district court, the defendants did label

their motion as a "motion to dismiss," but they stated in their papers that

because they attached affidavits and papers, they "intend for their[motion] to be

treated as one for summary judgment." The record reveals that the Browns

were adequately alerted to the scope of the defendants' motion because in their

response to the motion, they included a section labeled "summary judgment."

Moreover, in the text of their response, the Browns acknowledged that the

defendants intended to have their motion to dismiss treated as one for summary

judgment. Nonetheless, the Browns elected not to file any affidavits contesting

the facts asserted by the defendants.

Several months later, the district court granted the defendants' motion for

summary judgment, accepting the undisputed facts asserted by the defendants

in their papers. We find no merit to the Browns' assertion that the court should

have provided the Browns with notice of its intent to treat the motion to dismiss

as one for summary judgment. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b). The court need not

initiate such a notice if the moving party in its papers does so. The

admonishment provided in Rule 12(b) is designed to give the non-moving party

notice and the opportunity to file opposing affidavits as if the motion were filed

under Rule 56. Here, the Browns had both notice and the opportunity to file

opposing affidavits, but chose not to submit any factual materials. Even on

appeal, moreover, the Browns made no proffer of what they would file, nor did

they express disagreement with the facts of record.

The facts in this case are straightforward and do not entitle the Browns to relief

on the merits. The Browns owned real property in Bristol for which they

applied to the Bristol Planning Commission for subdivision approval. Approval

was granted, subject to completion of ten items of work. The Browns never

took an appeal from the City's conditional approval to contest the conditions.

The City contends that the work included in the conditional approval was never

completed and that the Browns never applied for "final approval." Rather, they

sought, with this action, to challenge the conditions collaterally or to claim that

the City could not require its approval for the subdivision. Their right to

challenge those issues, however, had long passed.

In circumstances where the Browns failed to challenge or to follow reasonable

procedural avenues to obtain approval for their subdivision, they cannot later

claim, when the interested governmental body insists on compliance with its

approval requirements, that their property was taken without due process. Cf.

Williamson County Regional Planning Comm'n v. Hamilton Bank, 473 U.S.

172, 194-97 (1985). Moreover, when the Browns began to sell the lots without

having obtained subdivision approval as required by law, the City had a right to

publish and record a notice that it had not granted final approval for the

subdivision. The Browns do not contend that the notice was in error, only that it

impaired their ability to bypass lawfully imposed conditions for approval of the

subdivision.

10

On these facts there can be no taking of property or slander of title. Finding the

Browns' claim meritless, we affirm.

AFFIRMED

You might also like

- Petition For Writ of ProhibitionDocument11 pagesPetition For Writ of ProhibitionNicholas T Steffens100% (1)

- Motion For Reconsideration - 12.21.19Document4 pagesMotion For Reconsideration - 12.21.19Michael JamesNo ratings yet

- Overview 6T40-45 TransmissionDocument14 pagesOverview 6T40-45 TransmissionLeigh100% (1)

- Bryant v. Washington Mut. Bank, 524 F. Supp. 2d 753Document19 pagesBryant v. Washington Mut. Bank, 524 F. Supp. 2d 753Marques YoungNo ratings yet

- Darcel D. Fisher Harris v. Harvey Schonbrun, 11th Cir. (2014)Document12 pagesDarcel D. Fisher Harris v. Harvey Schonbrun, 11th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- George A. Hunt, JR., Selective Service No. 9-45-45-1035 v. Local Board No. 197, 438 F.2d 1128, 3rd Cir. (1971)Document28 pagesGeorge A. Hunt, JR., Selective Service No. 9-45-45-1035 v. Local Board No. 197, 438 F.2d 1128, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Barbara Jean Thornton, A/K/A Barbara J. Cook, Marie Saunders, Defendants, 859 F.2d 151, 4th Cir. (1988)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Barbara Jean Thornton, A/K/A Barbara J. Cook, Marie Saunders, Defendants, 859 F.2d 151, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ina Frankel Abramson, Irving Hellman and Beatrice Hellman v. Pennwood Investment Corp., and Edward Nathan, Intervenor-Appellant, 392 F.2d 759, 2d Cir. (1968)Document5 pagesIna Frankel Abramson, Irving Hellman and Beatrice Hellman v. Pennwood Investment Corp., and Edward Nathan, Intervenor-Appellant, 392 F.2d 759, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Sedgwick Co. Sheriff's Office, 10th Cir. (2013)Document4 pagesBrown v. Sedgwick Co. Sheriff's Office, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Employment LitigationDocument17 pagesIn Re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Employment LitigationScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Frank A. Barton v. Sindall Transport, Inc, Floyd G. Martin, Richard W. Humphrey, 934 F.2d 318, 4th Cir. (1991)Document4 pagesFrank A. Barton v. Sindall Transport, Inc, Floyd G. Martin, Richard W. Humphrey, 934 F.2d 318, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Carol Mattingly, Individually, and Her Minor Children, Patricia E. Mattingly v. Gabriel Elias, Carol Mattingly, 482 F.2d 526, 3rd Cir. (1973)Document4 pagesCarol Mattingly, Individually, and Her Minor Children, Patricia E. Mattingly v. Gabriel Elias, Carol Mattingly, 482 F.2d 526, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Howard F. Ransom and Hazel B. Ransom, Cross-Appellants v. S & S Food Center, Inc. of Florida, D/B/A Rich Plan of Pensacola, Defendant - Cross-Appellee, 700 F.2d 670, 11th Cir. (1983)Document13 pagesHoward F. Ransom and Hazel B. Ransom, Cross-Appellants v. S & S Food Center, Inc. of Florida, D/B/A Rich Plan of Pensacola, Defendant - Cross-Appellee, 700 F.2d 670, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Andy L. Wallace v. City of Altus, Oklahoma, A Municipal Corporation, 465 F.2d 420, 10th Cir. (1972)Document3 pagesAndy L. Wallace v. City of Altus, Oklahoma, A Municipal Corporation, 465 F.2d 420, 10th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Dca Development Corporation, Debtors. Petition of Franchi Construction Co., Inc., 489 F.2d 43, 1st Cir. (1973)Document7 pagesIn The Matter of Dca Development Corporation, Debtors. Petition of Franchi Construction Co., Inc., 489 F.2d 43, 1st Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- A & B Trash Service, A Division of Astor-Bolden Enterprises, Incorporated v. Town of Shallotte, 14 F.3d 593, 4th Cir. (1993)Document3 pagesA & B Trash Service, A Division of Astor-Bolden Enterprises, Incorporated v. Town of Shallotte, 14 F.3d 593, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eighth CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eighth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alvin J. Barnett Robert L. Brock, Fred L. Anderson v. United States, 5 F.3d 545, 10th Cir. (1993)Document3 pagesAlvin J. Barnett Robert L. Brock, Fred L. Anderson v. United States, 5 F.3d 545, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems Et Al. v. Robinson Et Al.Document10 pagesMortgage Electronic Registration Systems Et Al. v. Robinson Et Al.Martin AndelmanNo ratings yet

- Burris v. United States, 10th Cir. (2008)Document7 pagesBurris v. United States, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- York v. HernandezDocument3 pagesYork v. HernandezNorthern District of California BlogNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph P. Candella, 487 F.2d 1223, 2d Cir. (1974)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Joseph P. Candella, 487 F.2d 1223, 2d Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third Circuit.: No. 12961. No. 12962Document2 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third Circuit.: No. 12961. No. 12962Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dawn Ball v. Hartman, 3rd Cir. (2010)Document5 pagesDawn Ball v. Hartman, 3rd Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument7 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Feibush - Motion To DismissDocument15 pagesFeibush - Motion To DismissPhiladelphiaMagazineNo ratings yet

- Roberts v. United States, 10th Cir. (2000)Document6 pagesRoberts v. United States, 10th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- William B. Richardson v. Dee E. Miller, 446 F.2d 1247, 3rd Cir. (1971)Document4 pagesWilliam B. Richardson v. Dee E. Miller, 446 F.2d 1247, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Francis X. Calo v. R. Morris Paine, 521 F.2d 411, 2d Cir. (1975)Document4 pagesFrancis X. Calo v. R. Morris Paine, 521 F.2d 411, 2d Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harvey B. Johnson v. Rac Corporation, 491 F.2d 510, 4th Cir. (1974)Document7 pagesHarvey B. Johnson v. Rac Corporation, 491 F.2d 510, 4th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Louis Howard Andres Cox v. William I. Koch, Individually and as Trustee De Son Tort of Mixson-Gray Trust-A, Mixson-Simmons-Gray Trust-B, Mixon-Simmons-Gray Trust-C, Mixsonsimmons-Gray Trust D, 77 F.3d 492, 10th Cir. (1996)Document3 pagesLouis Howard Andres Cox v. William I. Koch, Individually and as Trustee De Son Tort of Mixson-Gray Trust-A, Mixson-Simmons-Gray Trust-B, Mixon-Simmons-Gray Trust-C, Mixsonsimmons-Gray Trust D, 77 F.3d 492, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Berger v. White, 10th Cir. (2001)Document7 pagesBerger v. White, 10th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kahan, 415 U.S. 239 (1974)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Kahan, 415 U.S. 239 (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Michael Lorenzo Mary Lorenzo v. Andrew Griffith William Grogan, D/B/A Barnacle Bill's, Inc, 12 F.3d 23, 3rd Cir. (1993)Document8 pagesMichael Lorenzo Mary Lorenzo v. Andrew Griffith William Grogan, D/B/A Barnacle Bill's, Inc, 12 F.3d 23, 3rd Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Denise Desanctis v. Myrtle Hastings, 105 F.3d 646, 4th Cir. (1997)Document3 pagesDenise Desanctis v. Myrtle Hastings, 105 F.3d 646, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Phillip E. Beard, Trustee For Greater Pittsburgh Business Development Corp. v. Melvin A. Braunstein, An Individual, D/B/A M.A. Braunstein Co., 914 F.2d 434, 3rd Cir. (1990)Document22 pagesPhillip E. Beard, Trustee For Greater Pittsburgh Business Development Corp. v. Melvin A. Braunstein, An Individual, D/B/A M.A. Braunstein Co., 914 F.2d 434, 3rd Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Conyers V Bush - ORDER GRANTING DEFENDANTS' MOTIONS TO DISMISS 11-06-2006Document9 pagesConyers V Bush - ORDER GRANTING DEFENDANTS' MOTIONS TO DISMISS 11-06-2006Beverly TranNo ratings yet

- Not For Publication: AckgroundDocument6 pagesNot For Publication: Ackgroundbedford2006No ratings yet

- Walker v. City of Hutchinson, 352 U.S. 112 (1956)Document12 pagesWalker v. City of Hutchinson, 352 U.S. 112 (1956)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re: Paul J. Mraz, James E. Mraz Heidi Pfisterer Mraz, His Wife v. Pauline M. Bright Sommers Enterprises, Incorporated Gordon Schmidt Coldwell Banker Residential Affiliates, Incorporated Aaron Chicovsky William Ross Pederson, and John Doe, Counter-Offerer, 46 F.3d 1125, 4th Cir. (1995)Document5 pagesIn Re: Paul J. Mraz, James E. Mraz Heidi Pfisterer Mraz, His Wife v. Pauline M. Bright Sommers Enterprises, Incorporated Gordon Schmidt Coldwell Banker Residential Affiliates, Incorporated Aaron Chicovsky William Ross Pederson, and John Doe, Counter-Offerer, 46 F.3d 1125, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Annis v. Collins, 10th Cir. (2007)Document5 pagesAnnis v. Collins, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jeraldine D. Bryant v. United States Department of Agriculture, 967 F.2d 501, 11th Cir. (1992)Document7 pagesJeraldine D. Bryant v. United States Department of Agriculture, 967 F.2d 501, 11th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 6th Edited Appellate BriefDocument39 pages6th Edited Appellate Briefreuben_nieves1899No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Edmond C. Fletcher v. Courtney R. Young and Eleanor M. Young, His Wife, 222 F.2d 222, 4th Cir. (1955)Document3 pagesEdmond C. Fletcher v. Courtney R. Young and Eleanor M. Young, His Wife, 222 F.2d 222, 4th Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Angela Robinson v. Eric Hicks, 3rd Cir. (2012)Document4 pagesAngela Robinson v. Eric Hicks, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Yarber File 1Document29 pagesYarber File 1the kingfishNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.: Nos. 77-1751 77-1753 and 77-1761, 77-1762Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.: Nos. 77-1751 77-1753 and 77-1761, 77-1762Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Technical Color & Chemical Works, Inc., Creditor-Appellant v. Two Guys From Massapequa, Inc., Crib, Carriage & Toy Distributors, Inc., Debtors-Appellees, 327 F.2d 737, 2d Cir. (1964)Document8 pagesTechnical Color & Chemical Works, Inc., Creditor-Appellant v. Two Guys From Massapequa, Inc., Crib, Carriage & Toy Distributors, Inc., Debtors-Appellees, 327 F.2d 737, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Central States Underwater Contracting, Incorporated, A Kansas Corporation v. R. L. Morrison & Sons, Incorporated, A South Carolina Corporation, 45 F.3d 425, 4th Cir. (1995)Document4 pagesCentral States Underwater Contracting, Incorporated, A Kansas Corporation v. R. L. Morrison & Sons, Incorporated, A South Carolina Corporation, 45 F.3d 425, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gerard and Gemma Brault v. Town of Milton, 527 F.2d 730, 2d Cir. (1975)Document21 pagesGerard and Gemma Brault v. Town of Milton, 527 F.2d 730, 2d Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Craig V US - ORDER Dismissing Complaint (13 2009-06-17)Document6 pagesCraig V US - ORDER Dismissing Complaint (13 2009-06-17)tesibriaNo ratings yet

- Priority Send: CV 04-8425-VAP (Ex)Document6 pagesPriority Send: CV 04-8425-VAP (Ex)Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 29!541 Transient Aspects of Unloading Oil and Gas Wells With Coiled TubingDocument6 pages29!541 Transient Aspects of Unloading Oil and Gas Wells With Coiled TubingWaode GabriellaNo ratings yet

- 1-10 Clariant - Prasant KumarDocument10 pages1-10 Clariant - Prasant Kumarmsh43No ratings yet

- Final ME Paper I IES 2010Document18 pagesFinal ME Paper I IES 2010pajadhavNo ratings yet

- Resistor 1k - Vishay - 0.6wDocument3 pagesResistor 1k - Vishay - 0.6wLEDNo ratings yet

- BA5411 ProjectGuidelines - 2020 PDFDocument46 pagesBA5411 ProjectGuidelines - 2020 PDFMonisha ReddyNo ratings yet

- Patient Care Malaysia 2014 BrochureDocument8 pagesPatient Care Malaysia 2014 Brochureamilyn307No ratings yet

- Rfa TB Test2Document7 pagesRfa TB Test2Сиана МихайловаNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1: Semester Fall 2021 Data Warehousing - CS614Document3 pagesAssignment No. 1: Semester Fall 2021 Data Warehousing - CS614Hamza Khan AbduhuNo ratings yet

- Determination of Molecular Radius of Glycerol Molecule by Using R SoftwareDocument5 pagesDetermination of Molecular Radius of Glycerol Molecule by Using R SoftwareGustavo Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- MOFPED STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 - 2021 PrintedDocument102 pagesMOFPED STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 - 2021 PrintedRujumba DukeNo ratings yet

- Direct Marketing CRM and Interactive MarketingDocument37 pagesDirect Marketing CRM and Interactive MarketingSanjana KalanniNo ratings yet

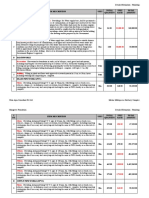

- 03 Marine Multispecies Hatchery Complex Plumbing Detailed BOQ - 23.10.2019Document52 pages03 Marine Multispecies Hatchery Complex Plumbing Detailed BOQ - 23.10.2019samir bendreNo ratings yet

- Universal Beams PDFDocument2 pagesUniversal Beams PDFArjun S SanakanNo ratings yet

- TelekomDocument2 pagesTelekomAnonymous eS7MLJvPZCNo ratings yet

- Star - 6 ManualDocument100 pagesStar - 6 ManualOskarNo ratings yet

- Fss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewDocument7 pagesFss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewhasanmuskaanNo ratings yet

- Bare Copper & Earthing Accessories SpecificationDocument14 pagesBare Copper & Earthing Accessories SpecificationJayantha SampathNo ratings yet

- How To Start A Fish Ball Vending Business - Pinoy Bisnes IdeasDocument10 pagesHow To Start A Fish Ball Vending Business - Pinoy Bisnes IdeasNowellyn IncisoNo ratings yet

- Product Bulletin 20Document5 pagesProduct Bulletin 20RANAIVOARIMANANANo ratings yet

- Good Quality Practices at NTPC KudgiDocument8 pagesGood Quality Practices at NTPC KudgisheelNo ratings yet

- 3471A Renault EspaceDocument116 pages3471A Renault EspaceThe TrollNo ratings yet

- System Description For Use With DESIGO XWORKS 17285 HQ enDocument48 pagesSystem Description For Use With DESIGO XWORKS 17285 HQ enAnonymous US9AFTR02100% (1)

- The Soyuzist JournalDocument15 pagesThe Soyuzist Journalcatatonical thingsNo ratings yet

- The Man Who Knew Too Much: The JFK Assassination TheoriesDocument4 pagesThe Man Who Knew Too Much: The JFK Assassination TheoriesedepsteinNo ratings yet

- Io TDocument2 pagesIo TPrasanth VarasalaNo ratings yet

- Coding Guidelines-CDocument71 pagesCoding Guidelines-CKishoreRajuNo ratings yet

- Windows XP, Vista, 7, 8, 10 MSDN Download (Untouched)Document5 pagesWindows XP, Vista, 7, 8, 10 MSDN Download (Untouched)Sheen QuintoNo ratings yet

- 5.1 - FMCSDocument19 pages5.1 - FMCSJon100% (1)

- Faculty Performance Appraisal Report (Draft1)Document3 pagesFaculty Performance Appraisal Report (Draft1)mina dote100% (1)