Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

870 F.

2d 655

49 Fair Empl.Prac.Cas. 754

Unpublished Disposition

NOTICE: Fourth Circuit I.O.P. 36.6 states that citation of

unpublished dispositions is disfavored except for establishing

res judicata, estoppel, or the law of the case and requires

service of copies of cited unpublished dispositions of the Fourth

Circuit.

Bessie Carpenter LOCUS, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

FAYETTEVILLE STATE UNIVERSITY, Robert Lemmons,

in his

official capacity as Head, Division of General Studies,

James Scurry, individually and in his official capacity as

Director of Career Planning and Placement, Charles A. Lyons,

individually and in his official capacity as Chancellor of

FSU, Valeria Fleming, individually and in her official

capacity, Matthew Jarmon, individually and in his official

capacity, Robert James, individually and in his official

capacity, Defendants-Appellees.

No. 88-2561.

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.

Argued Dec. 8, 1988.

Decided March 8, 1989.

Sidney Solomon Baron (Sidney S. Baron, P.A., on brief) for appellant.

Kaye Rosalind Webb, Assistant Attorney General (Lacy H. Thornburg,

Attorney General, North Carolina Department of Justice, on brief) for

appellees.

Before K.K. HALL, SPROUSE and WILKINSON, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

Bessie Carpenter Locus, the plaintiff in a civil rights action brought against

Fayetteville State University and several University employees, appeals the

order of the district court granting summary judgment in favor of the

defendants on her claim of civil conspiracy. Finding no error, we affirm.

I.

2

The plaintiff was employed by Fayetteville State University as an

administrative assistant. In the summer of 1985, a notice of openings for the

position of academic advisor was circulated and on June 21, 1985, the plaintiff

applied for the position. On July 17, 1985, the plaintiff received a letter from

Dr. Robert Lemons, one of the defendants and head of the Division of General

Studies, stating that a candidate for the position of academic advisor had been

chosen. The plaintiff subsequently learned that the person recommended for

the position was Gerald Winfrey. Convinced that Winfrey had been selected

solely because he was a male, the plaintiff filed a complaint with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC"). That complaint was

subsequently denied when EEOC found no cause as to discrimination and

issued a right-to-sue letter.

On May 2, 1986, the plaintiff filed a complaint in district court under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000e et seq., and 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983

alleging that the defendants were guilty of sex discrimination in denying her the

promotion to the position of academic advisor. In addition, the complaint

alleged that the defendants had harassed her in retaliation for filing a charge

with EEOC and also alleged intentional infliction of emotional distress by her

supervisor, James Scurry.

The plaintiff subsequently moved to amend her complaint in the district court

to include a claim of civil conspiracy against defendants Dr. Charles Lyons,

Chancellor of Fayetteville State University; Dr. Valeria Fleming, Provost and

Vice-Chancellor for Academic Affairs; Dr. Robert Lemons, head of the

Division of General Studies; James Scurry, director of Career Planning and

Placement; Matthew Jarmond, director of personnel; and Dr. Robert James,

coordinator of the Title III grant program, all in their official and individual

capacities. The motion was granted and the amended complaint was filed. In it

plaintiff alleged that the defendants were part of a civil conspiracy to deprive

her of a promotion and to increase the costs of her discovery. Specifically,

plaintiff alleged that the defendants conspired between and among themselves

to deprive her of a full and fair determination by EEOC of her sex

discrimination charge by providing false and misleading information during

EEOC's investigation.

5

The defendants moved for summary judgment on the civil conspiracy claim on

the ground that the claim was barred by the intracorporate conspiracy doctrine.

The district court agreed and by order dated May 20, 1988, granted the

defendants' motion dismissing the action as to defendants Lemons, Lyons,

Scurry, Fleming, Jarmond, James, and the University. On June 3, 1988, the

district court entered a final order on the civil conspiracy claim pursuant to

Fed.R.Civ.P. 54(b). It is from this order that plaintiff appeals.

II.

6

The intracorporate conspiracy doctrine had its genesis in Nelson Radio &

Supply Co. v. Motorola, Inc., 200 F.2d 911 (5th Cir.1952), cert. denied, 345

U.S. 925 (1953), an antitrust action based on an alleged conspiracy between the

defendant corporation and its officers, employees and agents. In dismissing the

action, the court stated:

It is basic in the law of conspiracy that you must have two persons or entities to

have a conspiracy. A corporation cannot conspire with itself any more than a

private individual can, and it is the general rule that the acts of the agent are the

acts of the corporation.

200 F.2d at 914.

Although it has been criticized, see Novotney v. Great American Federal

Savings & Loan Ass'n, 584 F.2d 1235 (3d Cir.1978), vacated on other grounds,

442 U.S. 366 (1979), the validity of the intracorporate conspiracy doctrine was

affirmed in Copperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp., 467 U.S. 752

(1984). It was recognized and adopted by this Court in Greenville Publishing

Co., Inc. v. Daily Reflector, Inc., 496 F.2d 391 (4th Cir.1974).

10

Appellant does not argue against the validity of the doctrine itself but argues

that its application should be limited to antitrust cases. The law of this Circuit

tells us otherwise.

11

In Buschi v. Kirven, 775 F.2d 1240 (4th Cir.1985), we found the doctrine

applicable in the civil rights context where suit was brought by dismissed state

hospital employees under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 and Sec. 1985(3) charging that

their discharges were the result of a conspiracy in violation of both their first

amendment and due process rights. Further, the intracorporate conspiracy

doctrine has been applied in the civil rights area by other courts, Dombrowski

v. Dowling, 459 F.2d 190, 196 (7th Cir.1972); Herrmann v. Moore, 576 F.2d

453 (2d Cir.1978), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 1003 (1978), Becker v. Russek, 518

F.Supp. 1040, 1045 (W.D.Va.1981), aff'd without opinion, 679 F.2d 876 (4th

Cir.1982); Eggleston v. Prince Edward Volunteer Rescue Squad, Inc., 569

F.Supp. 1344, 1352 (E.D.Va.1983), aff'd without opinion, 742 F.2d 1448 (4th

Cir.1984). We are not persuaded by appellant's argument that the doctrine

should be more limited, and her argument that the doctrine is not applicable to

civil rights or discrimination cases fails.

III.

12

Appellant argues that even if the doctrine is applicable in cases involving civil

rights or discrimination, it should not be applied here because the facts of this

case show it to fall within an exception to the doctrine.

13

Since the doctrine was first stated in Nelson, exceptions to it have been

recognized in certain cases. In Buschi, we noted that it has been held that the

doctrine does not apply where "the plaintiff has alleged that the corporate

employees were dominated by personal motives or where their actions

exceeded the bounds of their authority." Note, 13 Ga.L.Rev. 591 at 608. We

applied the first such exception in Greenville Publishing, supra, an antitrust

case involving competitors in the business of local advertising. In Greenville, a

defendant officer had a monetary interest in one of the newspapers involved in

the suit and therefore stood to benefit personally from the elimination of the

other newspaper. Thus, after approving the doctrine we noted that "an

exception may be justified when the [corporate] officer has an independent

personal stake in achieving the corporation's alleged objective." 496 F.2d at

399. The appellant has alleged no personal financial stake here.1

14

As to the second exception, appellant argues that defendants should not have

the benefit of the doctrine because they acted beyond their authority.2 We have

not had occasion to adopt or apply this exception and in view of the fact that

appellant has failed to allege facts in her complaint that would make this

exception applicable to her case, we need not do so now.3

IV.

15

We conclude that the intracorporate conspiracy doctrine prevents appellant

from prevailing on her civil conspiracy claim. Accordingly, the judgment of the

district court is affirmed.

16

AFFIRMED.

Appellant argues that the personal stake exception should be read to include not

only financial stake, but also bad faith and personal motives. We have not taken

such an expansive view of this exception and decline to do so now, particularly

in light of the fact that she has failed to allege any facts that would support such

an exception

In Buschi v. Kirven, supra, we noted that, though less well recognized, other

courts have held that unauthorized acts of an employee in furtherance of a

conspiracy may state a claim under Sec. 1985(3). Hodgin v. Jefferson, 447

F.Supp. 804 (D.Md.1978)

We decline to address other exceptions to the doctrine argued by the appellant.

They have not been adopted by this Court and they are not supported by the

facts

You might also like

- Laundrie Family's Motion To DismissDocument20 pagesLaundrie Family's Motion To DismissBrian Brant100% (2)

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeFrom EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Conveyance Bond PDFDocument2 pagesConveyance Bond PDFgwenda vadino100% (2)

- Nolo Press A Legal Guide For Lesbian and Gay Couples 11th (2002)Document264 pagesNolo Press A Legal Guide For Lesbian and Gay Couples 11th (2002)Felipe ToroNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Show Temp - PL PDFDocument16 pagesShow Temp - PL PDFHashim Warren100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Case ChartDocument14 pagesCiv Pro Case ChartMadeline Taylor DiazNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument10 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- MDS Motion For TRODocument58 pagesMDS Motion For TRORicardo de AndaNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Doctrines in Remedial LawDocument7 pagesDoctrines in Remedial LawreseljanNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Fayne W. Artrip v. Joseph A. Califano, JR., Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 569 F.2d 1298, 4th Cir. (1978)Document4 pagesFayne W. Artrip v. Joseph A. Califano, JR., Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 569 F.2d 1298, 4th Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ella Porter v. Richard S. Schweiker, in His Official Capacity As Secretary of Health and Human Services, 692 F.2d 740, 11th Cir. (1982)Document7 pagesElla Porter v. Richard S. Schweiker, in His Official Capacity As Secretary of Health and Human Services, 692 F.2d 740, 11th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Federal Judge Refuses Motion To Dismiss in Rossley Jr. v. Drake University (Anti-Male Discrimination)Document10 pagesFederal Judge Refuses Motion To Dismiss in Rossley Jr. v. Drake University (Anti-Male Discrimination)The College FixNo ratings yet

- Charles A. Damiano A/K/A Charles A. Damyn v. Florida Parole and Probation Commission and Jim Smith, The Attorney General of The State of Florida, 785 F.2d 929, 11th Cir. (1986)Document6 pagesCharles A. Damiano A/K/A Charles A. Damyn v. Florida Parole and Probation Commission and Jim Smith, The Attorney General of The State of Florida, 785 F.2d 929, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Peter J. Pallotta v. United States, 404 F.2d 1035, 1st Cir. (1968)Document6 pagesPeter J. Pallotta v. United States, 404 F.2d 1035, 1st Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. George W. McManus JR., 826 F.2d 1061, 4th Cir. (1987)Document4 pagesUnited States v. George W. McManus JR., 826 F.2d 1061, 4th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Thomas Dean Kirchhoff v. Major William D. McLarty Commanding Officer, Armed Forces Entrance & Examining Station, 453 F.2d 1097, 10th Cir. (1972)Document4 pagesThomas Dean Kirchhoff v. Major William D. McLarty Commanding Officer, Armed Forces Entrance & Examining Station, 453 F.2d 1097, 10th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Owen F. Lyons v. James L. Sullivan, Etc., 602 F.2d 7, 1st Cir. (1979)Document6 pagesOwen F. Lyons v. James L. Sullivan, Etc., 602 F.2d 7, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 5 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 773, 5 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8548 Betty J. Buckley v. Coyle Public School System, 476 F.2d 92, 10th Cir. (1973)Document7 pages5 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 773, 5 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8548 Betty J. Buckley v. Coyle Public School System, 476 F.2d 92, 10th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alfred Brough v. Strathmann Supply Co., Inc., and Mermaid Pools, Inc., Third-Party, 358 F.2d 374, 3rd Cir. (1966)Document6 pagesAlfred Brough v. Strathmann Supply Co., Inc., and Mermaid Pools, Inc., Third-Party, 358 F.2d 374, 3rd Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Craig A. Dell v. William A. Heard, JR., 532 F.2d 1330, 10th Cir. (1976)Document7 pagesCraig A. Dell v. William A. Heard, JR., 532 F.2d 1330, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joseph C. Jamieson v. William B. Robinson, Commissioner of Correction of Pennsylvania, and James F. Howard, Warden of State Correctional Institution, 641 F.2d 138, 3rd Cir. (1981)Document8 pagesJoseph C. Jamieson v. William B. Robinson, Commissioner of Correction of Pennsylvania, and James F. Howard, Warden of State Correctional Institution, 641 F.2d 138, 3rd Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Adrian Lopez Garcia v. Irba Cruz de Batista, 642 F.2d 11, 1st Cir. (1981)Document9 pagesAdrian Lopez Garcia v. Irba Cruz de Batista, 642 F.2d 11, 1st Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 23 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 505, 23 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 31,164 Marcia R. Lieberman v. Edward v. Gant, 630 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1980)Document14 pages23 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 505, 23 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 31,164 Marcia R. Lieberman v. Edward v. Gant, 630 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. John Doe, Witness, 628 F.2d 694, 1st Cir. (1980)Document4 pagesUnited States v. John Doe, Witness, 628 F.2d 694, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wyrough & Loser, Inc. v. Pelmor Laboratories, Inc., 376 F.2d 543, 3rd Cir. (1967)Document7 pagesWyrough & Loser, Inc. v. Pelmor Laboratories, Inc., 376 F.2d 543, 3rd Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cosco v. Uphoff, 10th Cir. (1997)Document5 pagesCosco v. Uphoff, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sidney A. Clark v. Donald Taylor, 710 F.2d 4, 1st Cir. (1983)Document14 pagesSidney A. Clark v. Donald Taylor, 710 F.2d 4, 1st Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Richard Winn David Ehrlich Newlin Corporation and Somerset of Virginia, Inc. v. Wayne L. Lynn, 941 F.2d 236, 3rd Cir. (1991)Document8 pagesRichard Winn David Ehrlich Newlin Corporation and Somerset of Virginia, Inc. v. Wayne L. Lynn, 941 F.2d 236, 3rd Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Michael Kevin Dupont v. Karin Saunders, Michael Kevin Dupont v. Karin Saunders, Hasan Amir, Gary Mosso, John MacNeil, 800 F.2d 8, 1st Cir. (1986)Document4 pagesMichael Kevin Dupont v. Karin Saunders, Michael Kevin Dupont v. Karin Saunders, Hasan Amir, Gary Mosso, John MacNeil, 800 F.2d 8, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 41 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 569, 41 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 36,535 Paula A. Donnellon v. Fruehauf Corporation, 794 F.2d 598, 11th Cir. (1986)Document5 pages41 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 569, 41 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 36,535 Paula A. Donnellon v. Fruehauf Corporation, 794 F.2d 598, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Edward Richard Eggert, 624 F.2d 973, 10th Cir. (1980)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Edward Richard Eggert, 624 F.2d 973, 10th Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Glenn Harrington v. United States of America, Stephen R. Walsh, JR., 673 F.2d 7, 1st Cir. (1982)Document6 pagesGlenn Harrington v. United States of America, Stephen R. Walsh, JR., 673 F.2d 7, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Anthony Orazio, Cross-Appellee v. Richard L. Dugger, Robert A. Butterworth, Cross-Appellants, 876 F.2d 1508, 11th Cir. (1989)Document9 pagesAnthony Orazio, Cross-Appellee v. Richard L. Dugger, Robert A. Butterworth, Cross-Appellants, 876 F.2d 1508, 11th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Samuel Douglass Harris and Melba Jean Glass, 441 F.2d 1333, 10th Cir. (1971)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Samuel Douglass Harris and Melba Jean Glass, 441 F.2d 1333, 10th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument8 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Michael A. Evans v. Duane Shillinger, Warden, and The Attorney General of Wyoming, 999 F.2d 547, 10th Cir. (1993)Document5 pagesMichael A. Evans v. Duane Shillinger, Warden, and The Attorney General of Wyoming, 999 F.2d 547, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Calhoun, 10th Cir. (2015)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Calhoun, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kenneth Fields v. Clifton T. Perkins Hospital, 4th Cir. (2015)Document6 pagesKenneth Fields v. Clifton T. Perkins Hospital, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ahmad v. Furlong, 435 F.3d 1196, 10th Cir. (2006)Document18 pagesAhmad v. Furlong, 435 F.3d 1196, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 16 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 802, 15 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8061 Harry Daniel Hicks v. Abt Associates, Inc., 572 F.2d 960, 3rd Cir. (1978)Document14 pages16 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 802, 15 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 8061 Harry Daniel Hicks v. Abt Associates, Inc., 572 F.2d 960, 3rd Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Stephen A. Walsh, in No. 15639 v. Miehle-Goss-Dexter, Inc., in No. 15640 v. Edward Stern and Co., Inc, 378 F.2d 409, 3rd Cir. (1967)Document10 pagesStephen A. Walsh, in No. 15639 v. Miehle-Goss-Dexter, Inc., in No. 15640 v. Edward Stern and Co., Inc, 378 F.2d 409, 3rd Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 31 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1310, 31 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 33,600 Melva A. Ray v. Robert P. Nimmo, Administrator, U.S. Veterans Administration, 704 F.2d 1480, 11th Cir. (1983)Document10 pages31 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1310, 31 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 33,600 Melva A. Ray v. Robert P. Nimmo, Administrator, U.S. Veterans Administration, 704 F.2d 1480, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John F. Ryan v. Charles D. Hatfield, 578 F.2d 275, 10th Cir. (1978)Document4 pagesJohn F. Ryan v. Charles D. Hatfield, 578 F.2d 275, 10th Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument15 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Irene Pacheco v. State of Kansas Department of Social Rehabilitation Services Peggy Wolfe Carol Rittmayer, 978 F.2d 1267, 10th Cir. (1992)Document7 pagesIrene Pacheco v. State of Kansas Department of Social Rehabilitation Services Peggy Wolfe Carol Rittmayer, 978 F.2d 1267, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gloria P. Sanchez-Mariani v. Herbert E. Ellingwood, 691 F.2d 592, 1st Cir. (1982)Document6 pagesGloria P. Sanchez-Mariani v. Herbert E. Ellingwood, 691 F.2d 592, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 19 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 991, 19 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 9175 Mildred E. Francis-Sobel v. University of Maine, Everett O. Ware, 597 F.2d 15, 1st Cir. (1979)Document4 pages19 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 991, 19 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 9175 Mildred E. Francis-Sobel v. University of Maine, Everett O. Ware, 597 F.2d 15, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jerry Larrivee v. MCC Supt., 10 F.3d 805, 1st Cir. (1993)Document5 pagesJerry Larrivee v. MCC Supt., 10 F.3d 805, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Marty Martinez, 776 F.2d 1481, 10th Cir. (1985)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Marty Martinez, 776 F.2d 1481, 10th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dawn RaidDocument3 pagesDawn RaidNithi100% (1)

- Grupo Unicomer 7.875 1apr2024 USDDocument387 pagesGrupo Unicomer 7.875 1apr2024 USDYimerson Tobias RiveraNo ratings yet

- Government of Goa: Electricity DepartmentDocument2 pagesGovernment of Goa: Electricity DepartmentGoan HospitalityNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure II QuizDocument1 pageCivil Procedure II QuizLEAZ CLEMENANo ratings yet

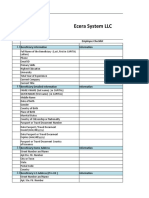

- Ecera System LLC: Employee Checklist InformationDocument5 pagesEcera System LLC: Employee Checklist InformationAnuran BordoloiNo ratings yet

- Ar 381-10 - Army Intelligence ActivitiesDocument30 pagesAr 381-10 - Army Intelligence ActivitiesMark CheneyNo ratings yet

- Proclamation and Attachment: Process To Compel Appearance - 3Document13 pagesProclamation and Attachment: Process To Compel Appearance - 3Rajshree ShekharNo ratings yet

- Dayao Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesDayao Vs ComelecrmelizagaNo ratings yet

- Annual Information Statement (AIS) : Part ADocument3 pagesAnnual Information Statement (AIS) : Part AbhavdeepsinhNo ratings yet

- LPGSDocument9 pagesLPGSPhilip S. GongarNo ratings yet

- New MemoDocument2 pagesNew MemoPHGreatlord GamingNo ratings yet

- District 2B Public DocumentsDocument123 pagesDistrict 2B Public DocumentsLocal 5 News (WOI-TV)No ratings yet

- Basics and History PDFDocument33 pagesBasics and History PDFTaraChandraChouhanNo ratings yet

- Standard Data Protection Clauses To Be Issued by The Commissioner Under S119A (1) Data Protection Act 2018Document36 pagesStandard Data Protection Clauses To Be Issued by The Commissioner Under S119A (1) Data Protection Act 2018andres.rafael.carrenoNo ratings yet

- Atlas Consolidated Mining and Development Corporation v. CIRDocument27 pagesAtlas Consolidated Mining and Development Corporation v. CIRTrish PichayNo ratings yet

- Huffine v. Haddon Et Al - Document No. 1Document4 pagesHuffine v. Haddon Et Al - Document No. 1Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Medalla, Jr. vs. Sto. TomasDocument9 pagesMedalla, Jr. vs. Sto. TomasChristian LucasNo ratings yet

- Chiranjit Lal Chowdhuri Vs The Union of India and Others On 4 December, 1950Document44 pagesChiranjit Lal Chowdhuri Vs The Union of India and Others On 4 December, 1950R VigneshwarNo ratings yet

- Conwi vs. Court of Tax Appeals, 213 SCRA 83, August 31, 1992Document14 pagesConwi vs. Court of Tax Appeals, 213 SCRA 83, August 31, 1992Jane BandojaNo ratings yet

- CE 2022 MPT Challan FormDocument1 pageCE 2022 MPT Challan FormArbab AliNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Miguel T. Caguioa, Ireneo B. Orlino Manuel D. VictorioDocument5 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Miguel T. Caguioa, Ireneo B. Orlino Manuel D. VictorioRubierosseNo ratings yet

- Tpa Assignment 5TH Sem (Shivam)Document16 pagesTpa Assignment 5TH Sem (Shivam)Atithi dev singhNo ratings yet

- GuidelinesIPCR-Regional ProvincialDocument4 pagesGuidelinesIPCR-Regional ProvincialFatima BagayNo ratings yet

- 01-Job Application FormDocument3 pages01-Job Application FormKing D ThreesixNo ratings yet

- Audit Final ExamDocument9 pagesAudit Final ExamNurfairuz Diyanah RahzaliNo ratings yet

- Amazon V FitzpatrickDocument63 pagesAmazon V FitzpatrickThe Fashion LawNo ratings yet