Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nego Week 1

Uploaded by

Victor Lim0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views12 pagesnego, ai

Original Title

Nego week 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentnego, ai

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views12 pagesNego Week 1

Uploaded by

Victor Limnego, ai

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

WEEK 1

I. Governing Law Act No. 2031 (enacted on Feb. 3, 1911 to take effect 90 days

after its publication in the Official Gazette.

II. Nature, Purpose and Function of Negotiable Instruments

Sec. 60, RA 7653

B. DEMAND DEPOSITS

Section 60. Legal Character. - Checks representing demand deposits do not have legal

tender power and their acceptance in the payment of debts, both public and private, is at

the option of the creditor: Provided, however, That a check which has been cleared and

credited to the account of the creditor shall be equivalent to a delivery to the creditor of

cash in an amount equal to the amount credited to his account

Traders Royal Bank vs. CA, 269 SCRA 15 (1997)

269 SCRA 15 Business Organization Corporation Law Piercing the Veil of Corporate

Fiction

Filriters Guaranty Assurance Corporation (FGAC) is the owner of several Central Bank

Certificates of Indebtedness (CBCI). These certificates are actually proof that FGAC has the

required reserve investment with the Central Bank to operate as an insurer and to protect

third persons from whatever liabilities FGAC may incur. In 1979, FGAC agreed to assign said

CBCI to Philippine Underwriters Finance Corporation (PUFC). Later, PUFC sold said CBCI to

Traders Royal Bank (TRB). Said sale with TRB comes with a right to repurchase on a date

certain. However, when the day to repurchase arrived, PUFC failed to repurchase said CBCI

hence TRB requested the Central Bank to have said CBCI be registered in TRBs name.

Central Bank refused as it alleged that the CBCI are not negotiable; that as such, the

transfer from FGAC to PUFC is not valid; that since it was invalid, PUFC acquired no valid title

over the CBCI; that the subsequent transfer from PUFC to TRB is likewise invalid.

TRB then filed a petition for mandamus to compel the Central Bank to register said CBCI in

TRBs name. TRB averred that PUFC is the alter ego of FGAC; that PUFC owns 90% of FGAC;

that the two corporations have identical sets of directors; that payment of said CBCI to PUFC

is like a payment to FGAC hence the sale between PUFC and TRB is valid. In short, TRB avers

that that the veil of corporate fiction, between PUFC and FGAC, should be pierced because

the two corporations allegedly used their separate identity to defraud TRD into buying said

CBCI.

ISSUE: Whether or not Traders Royal Bank is correct.

HELD: No. Traders Royal Bank failed to show that the corporate fiction is used by the two

corporations to defeat public convenience, justify wrong, protect fraud or defend crime or

where a corporation is a mere alter ego or business conduit of a person. TRB merely showed

that PUFC owns 90% of FGAC and that their directors are the same. The identity of PUFC

cant be maintained as that of FGAC because of this mere fact; there is nothing else which

could lead the court under the circumstance to disregard their corporate personalities.

Further, TRB cant argue that it was defrauded into buying those certificates. In the first

place, TRB as a banking institution is not ignorant about these types of transactions. It

should know for a fact that a certificate of indebtedness is not negotiable because the payee

therein is inscribed specifically and that the Central Bank is obliged to pay the named payee

only and no one else.

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

Eduque vs. Ocampo 86 Phil. 216

Facts: On 16 February 1935, Dr. Jose Eduque secured two loans from Mariano Ocampo de

Leon, Dona Escolastica delos Reyes and Don Jose M. Ocampo, with amount s of P40,000 and

P15,000, both payable within 20 years with interest of 5% per annum. Payment of the loans

was guaranteed by mortgage on real property. On 6 December 1943, Salvacion F. Vda de

Eduque, as administratrix of the estate of Dr. Jose Eduque, tendered payment by means of a

cashiers check representing Japanese War notes to Jose M. Ocampo, who refused payment.

By reason of such refusal, an action was brought and the cashiers check was deposited in

court. After trial, judgment was rendered against Ocampo compelling him to accept the

amount, to pay the expenses of consignation, etc. Ocampo accepted the judgment as to the

second loan but appealed as to the first loan.

Issue: Whether there is a tender of payment by means of a cashiers check representing

war notes.

Held: Japanese military notes were legal tender during the Japanese occupation; and

Ocampo impliedly accepted the consignation of the cashiers check when he asked the court

that he be paid the amount of the second loan (P15,000). It is a rule that a cashiers check

may constitute a sufficient tender where no objection is made on this ground.

III. Kinds of Negotiable Instruments

Secs. 184, 126 and 185, in relation to Sec. 1, NIL

PROMISSORY NOTES AND CHECKS

Sec. 184. Promissory note, defined. - A negotiable promissory note within the meaning of

this Act is an unconditional promise in writing made by one person to another, signed by the

maker, engaging to pay on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time, a sum certain

in money to order or to bearer. Where a note is drawn to the maker's own order, it is not

complete until indorsed by him.

Sec. 185. Check, defined. - A check is a bill of exchange drawn on a bank payable on

demand. Except as herein otherwise provided, the provisions of this Act applicable to a bill of

exchange payable on demand apply to a check.

Sec. 126. Bill of exchange, defined. - A bill of exchange is an unconditional order in writing

addressed by one person to another, signed by the person giving it, requiring the person to

whom it is addressed to pay on demand or at a fixed or determinable future time a sum

certain in money to order or to bearer.

In re:

I. FORM AND INTERPRETATION

Section 1. Form of negotiable instruments. - An instrument to be negotiable must conform to

the following requirements:chanroblesvirtuallawlibrary

(a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer;

(b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money;

(c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time;

(d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and

(e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise

indicated therein with reasonable certainty.

Moran vs. CA, 230 SCRA, 799

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

Facts: Petitioner spouses Moran maintained three joint accounts with respondent Citytrust

Banking Corporation. As a special privilege to the Morans, a pre-authorized transfer (PAT)

agreement was entered into by the parties. The PAT letter-agreement contained the

following provisions: (1) xxx the checks would be honored if the savings account has

sufficient balance to cover the overdraft; xxx (3) that the bank has the right to refuse to

effect transfer of funds at their sole and absolute option and discretion; (4) Citytrust is free

and harmless for any and all omissions or oversight in executing this automatic transfer of

funds. On December 12, 1983, petitioners, through Librada Moran, drew a check payable to

Petrophil Corporation. The next day, petitioners issued another check in favor of the same

corporation. Later, the bank dishonored the checks due to insufficiency of funds. As a

result, Petrophil refused to deliver the orders of petitioners on a credit. The non-delivery of

gasoline forced petitioners to temporarily stop business operations. Petitioners wrote

Citytrust claiming the dishonor of the checks caused them besmirched business and

personal reputation, shame and anxiety. Hence, they were contemplating filing legal actions,

unless the bank clears their name and paid for moral damages. The trial court dismissed the

complaint. The CA affirmed.

Issue: Whether or not petitioners had sufficient funds in their accounts when the bank

dishonored the checks in question.

Held: No. Under the clearing house rules, a bank processes a check on the date it was

presented for clearing. The available balance of December 14, 1983 was used by the bank in

determining whether or not there was sufficient cash deposited to fund the two checks,

although what was stamped on the dorsal side of the two checks was DAIF/12-15-83, since

December 15, 1983 was the actual date when the checks were processed. When petitioners

checks were dishonored, the available balance of the savings account, which was subject of

the PAT agreement, was not enough to cover either of the two checks.

Citytrust Banking Corp. vs. CA, 196 SCRA 553

Facts: Emme Herrero, businesswoman, made regular deposits with Citytrust Banking Corp.

at its Burgoa branch in Calamba, Laguna. She deposited the amount of P31, 500 in order to

amply cover 6 postdated checks she issued. All checks were dishonored due to insufficiency

of funds upon the presentment for encashment. Citytrust banking Corp. asserted that it was

due to Herreros fault that her checks were dishonored, for he inaccurately wrote his account

number in the deposit slip. RTC dismissed the complaint for lack of merit. CA reversed the

decision of RTC.

Issue: Whether or not Citytrust banking Corp. has the duty to honor checks issued by

Emme Herrero despite the failure to accurately stating the account number resulting to

insufficiency of funds for the check.

Held: Yes, even it is true that there was error on the account number stated in the deposit

slip, its is, however, indicated the name of Emme Herrero. This is controlling in

determining in whose account the deposit is made or should be posted. This is so because it

is not likely to commit an error in ones name than merely relying on numbers which are

difficult to remember. Numbers are for the convenience of the bank but was never intended

to disregard the real name of its depositors. The bank is engaged in business impressed with

public trust, and it is its duty to protect in return its clients and depositors who transact

business with it. It should not be a matter of the bank alone receiving deposits, lending out

money and collecting interests. It is also its obligation to see to it that all funds invested with

it are properly accounted for and duly posted in its ledgers.

Phil. Educ. Co., Inc. vs. Soriano, 39 SCRA 587

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

Facts:Enrique Montinola sought to purchase from Manila Post Office ten money orders of

200php each payable to E. P. Montinola. Montinola offered to pay with the money orders with

a private check. Private check were not generally accepted in payment of money orders, the

teller advised him to see the Chief of the Money Order Division, but instead of doing so,

Montinola managed to leave the building without the knowledge of the teller. Upon the

disappearance of the unpaid money order, a message was sent to instruct all banks that it

must not pay for the money order stolen upon presentment. The Bank of America received a

copy of said notice. However, The Bank of America received the money order and deposited

it to the appellants account upon clearance. Mauricio Soriano, Chief of the Money Order

Division notified the Bank of America that the money order deposited had been found to

have been irregularly issued and that, the amount it represented had been deducted from

the banks clearing account. The Bank of America debited appellants account with the same

account and give notice by mean of debit memo.

Issue: Whether or not the postal money order in question is a negotiable instrument

Held:No. It is not disputed that the Philippine postal statutes were patterned after similar

statutes in force in United States. The Weight of authority in the United States is that postal

money orders are not negotiable instruments, the reason being that in establishing and

operating a postal money order system, the government is not engaged in commercial

transactions but merely exercises a governmental power for the public benefit. Moreover,

some of the restrictions imposed upon money orders by postal laws and regulations are

inconsistent with the character of negotiable instruments. For instance, such laws and

regulations usually provide for not more than one endorsement; payment of money orders

may be withheld under a variety of circumstances.

Metrobank vs. CA, 194 SCRA, 169

FACTS: Eduardo Gomez opened an account with Golden Savings and deposited 38 treasury

warrants. All warrants were subsequently indorsed by Gloria Castillo as Cashier of Golden

Savings and deposited to its Savings account in Metrobank branch in Calapan, Mindoro. They

were sent for clearance. Meanwhile, Gomez is not allowed to withdraw from his account,

later, however, exasperated over Floria repeated inquiries and also as an accommodation

for a valued client Metrobank decided to allow Golden Savings to withdraw from proceeds

of the warrants. In turn, Golden Savings subsequently allowed Gomez to make withdrawals

from his own account. Metrobank informed Golden Savings that 32 of the warrants had been

dishonored by the Bureau of Treasury and demanded the refund by Golden Savings of the

amount it had previously withdrawn, to make up the deficit in its account. The demand was

rejected. Metrobank then sued Golden Savings.

ISSUE: Whether or not treasury warrants are negotiable instruments?

HELD: The Court held in the negative. The treasury warrants are not negotiable instruments.

Clearly stamped on their face is the word: non negotiable. Moreover, and this is equal

significance, it is indicated that they are payable from a particular fund, to wit, Fund 501. An

instrument to be negotiable instrument must contain an unconditional promise or orders to

pay a sum certain in money. As provided by Sec 3 of NIL an unqualified order or promise to

pay is unconditional though coupled with: 1st, an indication of a particular fund out of which

reimbursement is to be made or a particular account to be debited with the amount; or 2nd,

a statement of the transaction which give rise to the instrument. But an order to promise to

pay out of particular fund is not unconditional. The indication of Fund 501 as the source of

the payment to be made on the treasury warrants makes the order or promise to pay not

conditional and the warrants themselves non-negotiable. There should be no question that

the exception on Section 3 of NIL is applicable in the case at bar.

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

IV. Requisites of Negotiability of Negotiable Instruments

Sec. 1 - 4, 8 - 10, NIL; Art. 1179, Civil Code

Section 1. Form of negotiable instruments. - An instrument to be negotiable must

conform to the following requirements:

(a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer;

(b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money;

(c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time;

(d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and

(e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise

indicated therein with reasonable certainty.

Sec. 2. What constitutes certainty as to sum. - The sum payable is a sum certain within

the meaning of this Act, although it is to be paid:

(a) with interest; or

(b) by stated installments; or

(c) by stated installments, with a provision that, upon default in payment of any installment

or of interest, the whole shall become due; or

(d) with exchange, whether at a fixed rate or at the current rate; or

(e) with costs of collection or an attorney's fee, in case payment shall not be made at

maturity.

Sec. 3. When promise is unconditional. - An unqualified order or promise to pay is

unconditional within the meaning of this Act though coupled with:

(a) An indication of a particular fund out of which reimbursement is to be made or a

particular account to be debited with the amount; or

(b) A statement of the transaction which gives rise to the instrument.

But an order or promise to pay out of a particular fund is not unconditional.chan robles

virtual law library

Sec. 4. Determinable future time; what constitutes. - An instrument is payable at a

determinable future time, within the meaning of this Act, which is expressed to be payable:

(a) At a fixed period after date or sight; or

(b) On or before a fixed or determinable future time specified therein; or

(c) On or at a fixed period after the occurrence of a specified event which is certain to

happen, though the time of happening be uncertain.

An instrument payable upon a contingency is not negotiable, and the happening of the

event does not cure the defect.

Sec. 8. When payable to order. - The instrument is payable to order where it is drawn

payable to the order of a specified person or to him or his order. It may be drawn payable to

the order of:

(a) A payee who is not maker, drawer, or drawee; or

(b) The drawer or maker; or

(c) The drawee; or

(d) Two or more payees jointly; or

(e) One or some of several payees; or

(f) The holder of an office for the time being.

Where the instrument is payable to order, the payee must be named or otherwise indicated

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

therein with reasonable certainty.

Sec. 9. When payable to bearer. - The instrument is payable to

bearer:

(a) When it is expressed to be so payable; or

(b) When it is payable to a person named therein or bearer; or

(c) When it is payable to the order of a fictitious or non-existing person, and such fact was

known to the person making it so payable; or

(d) When the name of the payee does not purport to be the name of any

person; or

(e) When the only or last indorsement is an indorsement in blank.

Sec. 10. Terms, when sufficient. - The instrument need not follow the language of this Act,

but any terms are sufficient which clearly indicate an intention to conform to the

requirements hereof.

Inciong vs. CA, 257 SCRA 578

57 SCRA 578 Mercantile Law Negotiable Instruments in General Signature of Makers

Guaranty

FACTS: In February 1983, Rene Naybe took out a loan from Philippine Bank of

Communications (PBC) in the amount of P50k. For that he executed a promissory note in the

same amount. Naybe was able to convince Baldomero Inciong, Jr. and Gregorio Pantanosas

to co-sign with him as co-makers. The promissory note went due and it was left unpaid. PBC

demanded payment from the three but still no payment was made. PBC then sue the three

but PBC later released Pantanosas from its obligations. Naybe left for Saudi Arabia hence

cant be issued summons and the complaint against him was subsequently dropped. Inciong

was left to face the suit. He argued that that since the complaint against Naybe was

dropped, and that Pantanosas was released from his obligations, he too should have been

released.

ISSUE: Whether or not Inciong should be held liable.

HELD: Yes. Inciong is considering himself as a guarantor in the promissory note. And he was

basing his argument based on Article 2080 of the Civil Code which provides that guarantors

are released from their obligations if the creditors shall release their debtors. It is to be

noted however that Inciong did not sign the promissory note as a guarantor. He signed it as

a solidary co-maker.

A guarantor who binds himself in solidum with the principal debtor does not become a

solidary co-debtor to all intents and purposes. There is a difference between a solidary codebtor and a fiador in solidum (surety). The latter, outside of the liability he assumes to pay

the debt before the property of the principal debtor has been exhausted, retains all the other

rights, actions and benefits which pertain to him by reason of the fiansa; while a solidary codebtor has no other rights than those bestowed upon him.

Because the promissory note involved in this case expressly states that the three signatories

therein are jointly and severally liable, any one, some or all of them may be proceeded

against for the entire obligation. The choice is left to the solidary creditor (PBC) to

determine against whom he will enforce collection. Consequently, the dismissal of the case

against Pontanosas may not be deemed as having discharged Inciong from liability as well.

As regards Naybe, suffice it to say that the court never acquired jurisdiction over him.

Inciong, therefore, may only have recourse against his co-makers, as provided by law.

Rep. Planters Bank vs. CA, 216 SCRA 738

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

216 SCRA 738 Mercantile Law Negotiable Instruments in General Signature of Makers

FACTS: In 1979, World Garment Manufacturing, through its board authorized Shozo

Yamaguchi (president) and Fermin Canlas (treasurer) to obtain credit facilities from Republic

Planters Bank (RPB). For this, 9 promissory notes were executed.

The note became due and no payment was made. RPB eventually sued Yamaguchi and

Canlas. Canlas, in his defense, averred that he should not be held personally liable for such

authorized corporate acts that he performed inasmuch as he signed the promissory notes in

his capacity as officer of the defunct Worldwide Garment Manufacturing.

ISSUE: Whether or not Canlas should be held liable for the promissory notes.

HELD: Yes. The solidary liability of private respondent Fermin Canlas is made clearer and

certain, without reason for ambiguity, by the presence of the phrase joint and several as

describing the unconditional promise to pay to the order of Republic Planters Bank. Where

an instrument containing the words I promise to pay is signed by two or more persons,

they are deemed to be jointly and severally liable thereon.

Canlas is solidarily liable on each of the promissory notes bearing his signature for the

following reasons:

The promissory notes are negotiable instruments and must be governed by the Negotiable

Instruments Law.

Under the Negotiable lnstruments Law, persons who write their names on the face of

promissory notes are makers and are liable as such. By signing the notes, the maker

promises to pay to the order of the payee or any holder according to the tenor thereof.

Jimenez vs. Bucoy, 103 Phil. 40

Facts: In the proceedings in the intestate of Luther Young and Pacita Young who died in

1954 and 1952, respectively, Pacifica Jimenez presented for payment 4 promissory notes

signed by Pacita for different amounts totalling P21,000. Acknowledging receipt by Pacita

during the Japanese occupation, in the currency then prevailing, the Administrator

manifested willingness to pay provided adjustment of the sums be made in line with the

Ballantyne schedule. The claimant objected to the adjustment insisting on full payment in

accordance with the notes. The court held that the notes should be paid in the currency

prevailing after the war, and thus entitling Jimemez to recover P21,000 plus P2,000 as

attorneys fees. Hence, the appeal.

Issue: Whether the amounts should be paid, peso for peso; or whether a reduction should

be made in accordance with the Ballantyne schedule.

Held: If the loan was expressly agreed to be payable only after the war, or after liberation,

or became payable after those dates, no reduction could be effected, and peso-for-peso

payment shall be ordered in Philippine currency. The Ballantyne Conversion Table does not

apply where the monetary obligation, under the contract, was not payable during the

Japanese occupation. Herein, the debtor undertook to pay six months after the war, peso

for peso payment is indicated.

Ponce vs. CA, 90 SCRA 533; Kalalo vs. Luz, 34 SCRA 337

90 SCRA 533 Mercantile Law Negotiable Instruments Law Negotiable Instruments in

General Sum Certain in Money RA 529

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

FACTS: In 1969, Jesusa Afable and two others procured a loan from Nelia Ponce in the

amount of $194,016.29. In June 1969, Afable and her co-debtors executed a promissory note

in favor of Ponce in the peso equivalent of the loan amount which was P814,868.42. The

promissory note went due and was left unpaid despite demands from Ponce. This prompted

Ponce to sue Afable et al. The trial court ruled in favor of Ponce. The Court of Appeals initially

affirmed the trial court but it later reversed its decisions as it ruled that the promissory note

under consideration was payable in US dollars, and, therefore pursuant to Republic Act 529,

the transaction was illegal with neither party entitled to recover under the in pari delicto

rule.

ISSUE: Whether or not Ponce may recover.

HELD: Yes. RA 529 provides that an agreement to pay in dollars is null and void and of no

effect however what the law specifically prohibits is payment in currency other than legal

tender. It does not defeat a creditors claim for payment, as it specifically provides that

every other domestic obligation whether or not any such provision as to payment is

contained therein or made with respect thereto, shall be discharged upon payment in any

coin or currency which at the time of payment is legal tender for public and private debts. A

contrary rule would allow a person to profit or enrich himself inequitably at anothers

expense.

On the face of the promissory note, it says that it is payable in Philippine currency the

equivalent of the dollar amount loaned to Afable et al. It may likewise be pointed out that

the Promissory Note contains no provision giving the obligee the right to require payment in

a particular kind of currency other than Philippine currency, which is what is specifically

prohibited by RA No. 529. If there is any agreement to pay an obligation in a currency other

than Philippine legal tender, the same is null and void as contrary to public policy, pursuant

to Republic Act No. 529, and the most that could be demanded is to pay said obligation in

Philippine currency.

Rivera vs. Sps. Chua, G.R. No. 184458, Jan. 14, 2015

READ FULL TEXT this is new! XD

PNB vs. Rodriguez, G.R. No. 170325, Sept. 26, 2008

FACTS: Respondents-Spouses Erlando and Norma Rodriguez were clients of petitioner

Philippine National Bank (PNB), Amelia Avenue Branch, Cebu City. They maintained savings

and demand/checking accounts, namely, PNBig Demand Deposits (Checking/Current

Account No. 810624-6 under the account name Erlando and/or Norma Rodriguez), and

PNBig Demand Deposit (Checking/Current Account No. 810480-4 under the account name

Erlando T. Rodriguez).

The spouses were engaged in the informal lending business. In line with their business, they

had a discounting arrangement with the Philnabank Employees Savings and Loan

Association (PEMSLA), an association of PNB employees. Naturally, PEMSLA was likewise a

client of PNB Amelia Avenue Branch. The association maintained current and savings

accounts with petitioner bank.

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

PEMSLA regularly granted loans to its members. Spouses Rodriguez would rediscount the

postdated checks issued to members whenever the association was short of funds. As was

customary, the spouses would replace the postdated checks with their own checks issued in

the name of the members.

It was PEMSLAs policy not to approve applications for loans of members with outstanding

debts. To subvert this policy, some PEMSLA officers devised a scheme to obtain additional

loans despite their outstanding loan accounts. They took out loans in the names of

unknowing members, without the knowledge or consent of the latter. The PEMSLA checks

issued for these loans were then given to the spouses for rediscounting. The officers carried

this out by forging the indorsement of the named payees in the checks. In return, the

spouses issued their personal checks (Rodriguez checks) in the name of the members and

delivered the checks to an officer of PEMSLA. The PEMSLA checks, on the other hand, were

deposited by the spouses to their account.

Meanwhile, the Rodriguez checks were deposited directly by PEMSLA to its savings account

without any indorsement from the named payees. This was an irregular procedure made

possible through the facilitation of Edmundo Palermo, Jr., treasurer of PEMSLA and bank

teller in the PNB Branch. It appears that this became the usual practice for the parties. For

the period November 1998 to February 1999, the spouses issued sixty nine (69) checks, in

the total amount ofP2,345,804.00. These were payable to forty seven (47) individual payees

who were all members of PEMSLA.

Petitioner PNB eventually found out about these fraudulent acts. To put a stop to this

scheme, PNB closed the current account of PEMSLA. As a result, the PEMSLA checks

deposited by the spouses were returned or dishonored for the reason Account Closed. The

corresponding Rodriguez checks, however, were deposited as usual to the PEMSLA savings

account. The amounts were duly debited from the Rodriguez account. Thus, because the

PEMSLA checks given as payment were returned, spouses Rodriguez incurred losses from

the rediscounting transactions.

ISSUE: Whether the subject checks are payable to order or to bearer and who bears the

loss?

HELD: In the case at bar, respondents-spouses were the banks depositors. The checks were

drawn against respondents-spouses accounts.

PNB, as the drawee bank, had the

responsibility to ascertain the regularity of the indorsements, and the genuineness of the

signatures on the checks before accepting them for deposit. Lastly, PNB was obligated to

pay the checks in strict accordance with the instructions of the drawers. Petitioner

miserably failed to discharge this burden.

The checks were presented to PNB for deposit by a representative of PEMSLA absent any

type of indorsement, forged or otherwise. The facts clearly show that the bank did not pay

the checks in strict accordance with the instructions of the drawers, respondents-spouses.

Instead, it paid the values of the checks not to the named payees or their order, but to

PEMSLA, a third party to the transaction between the drawers and the payees.

Moreover, PNB was negligent in the selection and supervision of its employees. The

trustworthiness of bank employees is indispensable to maintain the stability of the banking

industry. Thus, banks are enjoined to be extra vigilant in the management and supervision

of their employees.

HSBC vs. CIR, G.R. No. 166018, June 4, 2014

Facts: The Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company (PLDT) drew a check on the

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

Hongkong & Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) in the latters favor for P14,608.05, and

sent it through mail. The check fell into the hands of Florentino Changco, who was able to

erase the name of the payee and substituted his own, and deposited the altered check in his

current account with the Peoples Bank and Trust Co. (PBTC). The check was cleared by

HSBC, and PBTC credited Changco the amount. The alteration was known when the

cancelled check was returned to PLDT. HSBC requested PBTC to refund the amount, but the

latter refused.

Issue: Whether HSBC can claim reimbursement from PBTC.

Held: A person who presents fro payment checks guarantees the genuineness of the check,

and the drawee bank need to concern itself with nothing but the genuineness of the

signature, and the state of the account with it of the drawee. If at all, whatever remedy,

whatever remedy HSBC has would lie not against PBTC but as against the party responsible

for changing the name of the payee (i.e. Changco). Its failure to call the attention of PBTC as

to such alteration until after the lapse of 27 days would, in the light of Central Bank Circular

9 (24-hour clearing house rule), negate whatever right it might have had against PBTC.

V. Matters which does not affect

Negotiable Instruments

negotiability/ Rules of Construction on

Secs. 5 7, 11, 12, 17, 24, 73, NIL

Sec. 5. Additional provisions not affecting negotiability. - An instrument which

contains an order or promise to do any act in addition to the payment of money is not

negotiable. But the negotiable character of an instrument otherwise negotiable is not

affected by a provision which:

(a) authorizes the sale of collateral securities in case the instrument be not paid at maturity;

or

(b) authorizes a confession of judgment if the instrument be not paid at maturity; or

(c) waives the benefit of any law intended for the advantage or protection of the obligor; or

(d) gives the holder an election to require something to be done in lieu of payment of money.

But nothing in this section shall validate any provision or stipulation otherwise illegal.

Sec. 6. Omissions; seal; particular money. - The validity and negotiable character of an

instrument are not affected by the fact that:

(a) it is not dated; or

(b) does not specify the value given, or that any value had been given therefor; or

(c) does not specify the place where it is drawn or the place where it is payable; or

(d) bears a seal; or

(e) designates a particular kind of current money in which payment is to be made.

But nothing in this section shall alter or repeal any statute requiring in certain cases the

nature of the consideration to be stated in the instrument.

Sec. 7. When payable on demand. - An instrument is payable on

demand:

(a) When it is so expressed to be payable on demand, or at sight, or on presentation; or

(b) In which no time for payment is expressed.

Where an instrument is issued, accepted, or indorsed when overdue, it is, as regards the

person so issuing, accepting, or indorsing it, payable on demand.

Sec. 11. Date, presumption as to. - Where the instrument or an acceptance or any

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

indorsement thereon is dated, such date is deemed prima facie to be the true date of the

making, drawing, acceptance, or indorsement, as the case may be.

Sec. 12. Ante-dated and post-dated. - The instrument is not invalid for the reason only

that it is ante-dated or post-dated, provided this is not done for an illegal or fraudulent

purpose. The person to whom an instrument so dated is delivered acquires the title thereto

as of the date of delivery.

CONSIDERATION

Sec. 24. Presumption of consideration. - Every negotiable instrument is deemed prima

facie to have been issued for a valuable consideration; and every person whose signature

appears thereon to have become a party thereto for value.

Sec. 73. Place of presentment. - Presentment for payment is made at the proper place:

(a) Where a place of payment is specified in the instrument and it is there presented;

(b) Where no place of payment is specified but the address of the person to make payment

is given in the instrument and it is there presented;

(c) Where no place of payment is specified and no address is given and the instrument is

presented at the usual place of business or residence of the person to make payment;

(d) In any other case if presented to the person to make payment wherever he can be found,

or if presented at his last known place of business or residence.

VI. Parties to Negotiable Instruments; Capacities

a.

Promissory Notes

1. Maker

2. Payee

3. Indorser/s

b. Bill of Exchange

1.

2.

3.

4.

Drawer

Drawee

Payee

Indorser

VII. Consideration in Negotiable Instruments

Secs. 24 29, NIL

II. CONSIDERATION

Sec. 24. Presumption of consideration. - Every negotiable instrument is deemed prima

facie to have been issued for a valuable consideration; and every person whose signature

appears thereon to have become a party thereto for value.

Sec. 25. Value, what constitutes. Value is any consideration sufficient to support a

simple contract. An antecedent or pre-existing debt constitutes value; and is deemed such

whether the instrument is payable on demand or at a future time.

Sec. 26. What constitutes holder for value. - Where value has at any time been given

for the instrument, the holder is deemed a holder for value in respect to all parties who

become such prior to that time.

Negotiable Instruments Law

Dean Lope Feble

Aculeus Iustitia Notes

Sec. 27. When lien on instrument constitutes holder for value. Where the holder has a lien

on the instrument arising either from contract or by implication of law, he is deemed a

holder for value to the extent of his lien.

Sec. 28. Effect of want of consideration. - Absence or failure of consideration is a

matter of defense as against any person not a holder in due course; and partial failure of

consideration is a defense pro tanto, whether the failure is an ascertained and liquidated

amount or otherwise.

Sec. 29. Liability of accommodation party. - An accommodation party is one who has

signed the instrument as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser, without receiving value

therefor, and for the purpose of lending his name to some other person. Such a person is

liable on the instrument to a holder for value, notwithstanding such holder, at the time of

taking the instrument, knew him to be only an accommodation party.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Swiss BankDocument14 pagesSwiss BankVrinda GoyalNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Tax Digests and Doctrines of 3D BATCH 2012 under Atty. Gonzales TCC, LGC and RemediesDocument44 pagesTax Digests and Doctrines of 3D BATCH 2012 under Atty. Gonzales TCC, LGC and RemediesLorenzo MartinezNo ratings yet

- Capital Market and Money MarketDocument17 pagesCapital Market and Money MarketSwastika Singh100% (1)

- A2010 Torts DigestsDocument179 pagesA2010 Torts Digestscmv mendoza100% (2)

- Statement 01-DEC-22 AC 50882755 03042555 PDFDocument5 pagesStatement 01-DEC-22 AC 50882755 03042555 PDFferuzbekNo ratings yet

- Dante A. Lim-Legal Ethics-CAse DigestDocument29 pagesDante A. Lim-Legal Ethics-CAse DigestVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Scotia Branch Statement SummaryDocument2 pagesScotia Branch Statement SummaryMd. Mahmudur RahmanNo ratings yet

- MT103 Saud Arabia 3,8MDocument2 pagesMT103 Saud Arabia 3,8Mterihinch87No ratings yet

- Torts - Case Digest Set 1Document24 pagesTorts - Case Digest Set 1Zaira Gem GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Montilla vs Hilario: Politician as counselDocument4 pagesMontilla vs Hilario: Politician as counselVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Civ2 NotesDocument62 pagesCiv2 NotesVictor LimNo ratings yet

- LTD Case Digests VicDocument11 pagesLTD Case Digests VicVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Deductible Losses for Income Tax PurposesDocument12 pagesDeductible Losses for Income Tax PurposesVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Bir Ruling Da 244 2005Document8 pagesBir Ruling Da 244 2005Eunice SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Dante LIm Engagement LetterDocument1 pageDante LIm Engagement LetterVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Rules of Ethical ConductDocument10 pagesRules of Ethical ConductVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Syllabus July 23Document1 pageCriminal Procedure Syllabus July 23Victor LimNo ratings yet

- Labor Law 2Document2 pagesLabor Law 2Victor LimNo ratings yet

- Torts and Damages 2nd MEETINGDocument74 pagesTorts and Damages 2nd MEETINGVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Evidence Reviewer 2016-2017Document67 pagesEvidence Reviewer 2016-2017Victor LimNo ratings yet

- Dante LIm Engagement LetterDocument1 pageDante LIm Engagement LetterVictor LimNo ratings yet

- 2015 Tax Syllabus Updated-FinalDocument126 pages2015 Tax Syllabus Updated-FinalChiefJusticeLaMzNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument8 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledVictor LimNo ratings yet

- ROS v. DARDocument13 pagesROS v. DARVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument11 pagesCourse OutlinemzhleanNo ratings yet

- DAR Rulings on Land Reform and Livestock FarmingDocument8 pagesDAR Rulings on Land Reform and Livestock FarmingVictor LimNo ratings yet

- DANTE A. LimDocument1 pageDANTE A. LimVictor LimNo ratings yet

- 2013 Syllabus Legal and Judicial EthicsDocument5 pages2013 Syllabus Legal and Judicial EthicsKathleen Catubay SamsonNo ratings yet

- Assignment Labor LawDocument7 pagesAssignment Labor LawVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Justices of The Supreme CourtDocument1 pageJustices of The Supreme CourtVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Wills DigestDocument4 pagesWills DigestVictor LimNo ratings yet

- Week 10Document8 pagesWeek 10Victor LimNo ratings yet

- Rights and obligations in marriage; donation validityDocument2 pagesRights and obligations in marriage; donation validityVictor LimNo ratings yet

- RMC 40 2003Document4 pagesRMC 40 2003Victor LimNo ratings yet

- PoliDocument1 pagePoliVictor LimNo ratings yet

- UPI Error and Response Codes 2 9Document73 pagesUPI Error and Response Codes 2 9shailshasabeNo ratings yet

- Imp SipDocument59 pagesImp Sipvenkatesh telangNo ratings yet

- Anexo 1. Homologacion Plan de CuentasDocument180 pagesAnexo 1. Homologacion Plan de CuentasJesús FuentesNo ratings yet

- Global Reciprocal College Receivable Financing DocumentDocument10 pagesGlobal Reciprocal College Receivable Financing Documentsharielles /No ratings yet

- Detailed StatementDocument6 pagesDetailed StatementSantosh Kumar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Liaquat Ahamed: Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke The WorldDocument4 pagesLiaquat Ahamed: Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke The WorldMessi CakeNo ratings yet

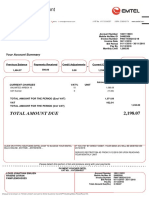

- Statement of Account VAT Invoice: Total Amount DueDocument1 pageStatement of Account VAT Invoice: Total Amount DueJonathan EmilienNo ratings yet

- CRF - For All Customers PDFDocument3 pagesCRF - For All Customers PDFVipan KumarNo ratings yet

- Financial Management 2E: Rajiv Srivastava - Dr. Anil Misra Solutions To Numerical ProblemsDocument5 pagesFinancial Management 2E: Rajiv Srivastava - Dr. Anil Misra Solutions To Numerical ProblemsParesh ShahNo ratings yet

- Cashless IndiaDocument2 pagesCashless Indiaanuj joshiNo ratings yet

- BS en 287Document7 pagesBS en 287Chris Thomas0% (1)

- WithdrawalsDocument1 pageWithdrawalskamal waniNo ratings yet

- Formulario Petición HASS, COOSA (HRS Systems)Document2 pagesFormulario Petición HASS, COOSA (HRS Systems)presto prestoNo ratings yet

- Zonal OfficeDocument1 pageZonal OfficeDeeprajNo ratings yet

- Racpc Ayyappanthangal - Google SearchDocument1 pageRacpc Ayyappanthangal - Google SearchBharat AllahanNo ratings yet

- Account Details and Transaction History SummaryDocument11 pagesAccount Details and Transaction History Summaryizzat emirNo ratings yet

- ATM-e-Banking Mobile Banking Request Form For CBS Customers PDFDocument1 pageATM-e-Banking Mobile Banking Request Form For CBS Customers PDFSupdt. of Post offices Kanpur (M) Dn. KanpurNo ratings yet

- Upstart Research ReportDocument7 pagesUpstart Research ReportAdfgatLjsdcolqwdhjpNo ratings yet

- Ledger Name Opening BalanceDocument3 pagesLedger Name Opening BalanceArista TechnologiesNo ratings yet

- PFMS Generated Print Payment Advice: To, The Branch HeadDocument2 pagesPFMS Generated Print Payment Advice: To, The Branch HeadPrakash panjiyarNo ratings yet

- Mukesh Surana's Balance Sheet and Profit & Loss StatementDocument5 pagesMukesh Surana's Balance Sheet and Profit & Loss StatementSURANA1973No ratings yet

- Teller - Transaction: Concept-Since The TELLER Application Will Be One and There Will Be Different Types of TransactionsDocument5 pagesTeller - Transaction: Concept-Since The TELLER Application Will Be One and There Will Be Different Types of TransactionsKamran MallickNo ratings yet

- Payment Gateway PlayerDocument5 pagesPayment Gateway PlayerHilmanie RamadhanNo ratings yet

- DBS Bank LTD - Credit Update - 140214Document7 pagesDBS Bank LTD - Credit Update - 140214Invest StockNo ratings yet

- Shanchay Patra BB ReceiptDocument5 pagesShanchay Patra BB Receiptkhan_sadiNo ratings yet