Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mumford Speedy Trial Dismiss

Uploaded by

Maxine BernsteinCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mumford Speedy Trial Dismiss

Uploaded by

Maxine BernsteinCopyright:

Available Formats

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 1 of 13

J. Morgan Philpot (Oregon Bar No. 144811)

Marcus R. Mumford (admitted pro hac vice)

405 South Main, Suite 975

Salt Lake City, UT 84111

(801) 428-2000

morgan@jmphilpot.com

mrm@mumfordpc.com

Attorneys for Defendant Ammon Bundy

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff,

v.

AMMON BUNDY, et al,

Defendants.

Case No. 3:16-cr-00051-BR

AMMON BUNDYS MOTION TO

DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

**Evidentiary Hearing and

Oral Argument Requested**

The Honorable Anna J. Brown

Defendant Ammon Bundys rights as protected by the Speedy Trial Act, 18 U.S.C.

3161-3174 (the Act or STA), and the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, have been

violated. Accordingly, Mr. Bundy moves to dismiss with prejudice. The Courts April 11, 2016

order held that unless and until a Defendant has a factual basis to assert an actual speedy-trial

violation, a motion to dismiss on that basis is premature and should not be filed. [Doc. 389 at 5]

As set forth below, the STA clock as to Mr. Bundy expired, at least, as of August 29, 2016. The

Ninth Circuit has made clear that so long as a defendant brings his motion to dismiss under the

STA prior to trial, it is timely under the STA, and the district court must dismiss if a violation is

found. United States v. Alvarez-Perez, 629 F.3d 1053, 1060 (9th Cir. 2010).

In an effort to avoid compliance with the 70-day STA clock, at the behest of the

government and over the repeated objections of Mr. Bundy and his rights to a speedy trial, the

Court has nevertheless required waivers of STA rights, and has invoked the ends of justice

provisions of the Act to delay and reschedule the trial date and to exclude time from the STA

DEFENDANT AMMON BUNDYS MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

-1-

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 2 of 13

clock between March 6 and September 7, 2016. [See Docs. 284, 289, 389, and 930] This

purported exclusion by a general order of complexity and the Courts requirement that a

defendant prospectively waive his STA rights are both directly prohibited by clear United States

Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit precedent. The fact that the Court rescheduled the trial date at

the governments insistence, requiring at the time that defendants choose between a speedy and

fair trial through the impermissible use of waivers, while objecting to and having the Court

deny Mr. Bundys attempts to obtain a fair trial, combined with its errant management of the

STA clock, demonstrates the governments tactical delay in prejudicing Mr. Bundys rights.

Because both the STA overrun and the tactical delay employed by the government have

taken place despite the immediate and repeated assertion of speedy trial rights by Mr. Bundy,

and because the Courts errant order of complexity was entered and maintained over the plain

objection of Mr. Bundy and his co-defendants, the dismissal in this case must be with prejudice.

This motion is based on the attached Memorandum of Law and Authorities, the records and

pleadings on file with the court, all matters of which the court may take judicial notice, and such

other evidence and argument as may be presented. Mr. Bundy hereby requests oral argument and

an evidentiary hearing on this motion.

CERTIFICATE OF CONFERRAL

When Mr. Bundys counsel raised these issues with the government, it indicated that it

intends to oppose this motion.

Respectfully submitted this 5th day of September, 2016.

/s/ Marcus R. Mumford

Marcus R. Mumford

J. Morgan Philpot

Attorneys for Ammon Bundy

DEFENDANT AMMON BUNDYS MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

-2-

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 3 of 13

J. Morgan Philpot (Oregon Bar No. 144811)

Marcus R. Mumford (admitted pro hac vice)

405 South Main, Suite 975

Salt Lake City, UT 84111

(801) 428-2000

morgan@jmphilpot.com

mrm@mumfordpc.com

Attorneys for Defendant Ammon Bundy

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff,

v.

AMMON BUNDY, et al,

Defendants.

Case No. 3:16-cr-00051-BR

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF

DEFENDANT AMMON BUNDYS

MOTION TO DISMISS FOR

IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

The Honorable Anna J. Brown

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

At the outset Ammon and Ryan Bundy advocated adamantly that they were entitled

to a trial date no later than mid-April 2016. [Doc. 846 at 6] The Court set a trial date for April

19, 2016. [Docs. 147, 148, 149, 150, 207, 208, 209, 293] This was within the STAs 70-day

period, but, on February 22, the government moved to vacate based upon the cases purported

complexity and to allow, inter alia, for what it described as the most complicated discovery

in the history of the district. [Doc. 185 at 2] On March 9, the Court granted the governments

request, over Mr. Bundys objection, and later set trial for September 7. [Docs. 289, 846 at 6]

Mr. Bundy objected to the February 22 motion to avoid getting buried in a mountain of

discovery, especially digital data, while he was incarcerated with limited ability to review such

matters (including thousands of hours of video). By granting that motion, the Court tactically

gave the government more than double the time set by the STA to review evidence and prepare

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 4 of 13

for trial, in the process dumping terabytes of data on Mr. Bundy, more than he could possibly

review before trial. But then, after giving the government the time it needed to prepare for trial,

the Court proceeded to compress Defendants timeline to review evidence and prepare for trial,

blaming Mr. Bundys objection, which the Court overruled, for the fact that there was no

flexibility in the schedule. [Doc. 455] Indeed, the Court went further, implementing a policy,

disallowed by the Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit (cited below), to mandate that any defendant

who dared request time to review the governments voluminous discovery prospectively waive

claim to the STAs protection. See 6/15/2016 Hrg. at 30 (If your client wants to waive his

speedy trial rights then the September 7 trial date may be adjusted for him.); id. at 31 (Ive

simply said that any defendant who affirmatively waives speedy trial rights need not continue to

prepare for trial on September 7.); [see also Docs. 458, 562, and 582] (same). To summarize:

the Court granted the governments motion purporting to exclude its delay under the STA

based on a prohibited complexity order while depriving Defendants of the ability to apply

the STA as it expressly contemplates. See 3161(h)(1)(D); Zedner v. United States, 547 U.S.

489, 497 (2006) (To provide the necessary flexibility, the Act includes a long and detailed list

of periods of delay that are excluded in computing the time . See 3161(h).).

Illustrating this point, on April 27, 2016, Mr. Bundy moved for a continuance based on

due process and Fed. R. Crim. P. 12(c)(2), making clear:

If the Court is disinclined to grant the continuance Mr. Bundy is forced to

make the untenable choice between a speedy trial and a fair one. Neither the

[STA] nor the Sixth Amendment requires that choice, and the Fifth Amendment

due process clause prohibits it. Thus, if the Court denies this request , Mr.

Bundy moves alternatively for relief from prejudicial joinder and for a new,

immediate trial date, within the next 30 days, where he can defend himself and the

Malheur protest at trial . If Mr. Bundy is unable to meaningfully and fairly

engage in credible and diligent pre-trial litigation and motion practice while

the government piles terabytes of discovery data here and pursues a separate but

related prosecution in Nevada, there is no purpose served whatsoever in the

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 5 of 13

prolonged pre-trial incarceration of himself and his colleges here in Oregon who

all share (along with their families) its attendant hardships.

[Doc. 470] In other words, Mr. Bundy initially requested to go to trial within 30 days,

suspecting that the governments request for delay to produce volumes of discovery was mere

pretext for one-sided delay, tactically benefitting its trial strategy without giving Defendants the

reciprocal opportunity to review the governments discovery.1 The Court later confirmed the

one-sided nature of its ruling by denying Mr. Bundys June 30, 2016 request to continue the trial.

Mr. Bundys request was based on, inter alia, the Courts complexity ruling, where it

recognized that Defendants custody status necessarily slows and complicates preparation for

pretrial motions and trial, and that the governments two initial volumes of discovery consist

of approximately 3,500 pages of materials including only investigative reports, affidavits, and

warrant materials, and the government expects to provide a substantial amount of additional

discovery as it becomes available, justif[ying] a finding of excludable delay under the Speedy

Trial Act. [Doc. 289 at 5] The Court ruled that the considerations it relied on in granting the

governments request did not apply to Mr. Bundys request, for time to review the governments

voluminous discovery because, despite the voluminous nature of the discovery, both Ammon

and Ryan Bundy are unquestionably aware of the fundamental facts underlying this case and

already know the primary evidence on which the government and co-Defendants will rely.

[Doc. 846 at 10] In other words, the Court granted the governments request for delay based on

the purported complexity of the case, including its representations that the discovery in this

1

In United States v. Koerber, 2014 WL 4060618, at *5 (D. Utah Aug. 14, 2014), revd on other

grounds, 813 F.3d 1262 (10th Cir. 2016), the court explained that 3161(h)(7) requires a valid

reason for the volume of discovery at issue to justify the ends-of-justice being invoked over

the publics and defendants interests in a speedy trial, and that the court must inquire into the

nature and relative importance of the discovery. Without this, the government might bypass

speedy trial rights by dumping hundreds of thousands of irrelevant pages of so-called discovery

in a defendants lap and prolong its investigation, virtually indefinitely.

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 6 of 13

case was the most complicated in the history of the district, but denied Mr. Bundys

reciprocal request to time to review that discovery because the matter was not so complex as to

require that he have that time to review the governments discovery. [Id.] This inconsistency

helps establish a violation of the Act and why this case should be dismissed with prejudice.

I. THE COURTS COMPLEXITY RULING DOES NOT TOLL TIME UNDER THE STA.

On March 9, the Court granted the governments request for delay, provisionally

finding excludable delay without resetting a trial date, and purporting to exclude time based on

a general finding of complexity under 3161(h)(7)(A). [Docs. 289 at 5, 846 at 6] But the plain

text of 3161(h)(7)(a) does not provide for such an order provisionally excluding time or

entering an overarching complexity finding, and the applicable case law expressly disallows it.

As a matter of first principles, 3161(h)(7)(a) only contemplates an exclusion of time where the

Court grants a continuance, and the issue of complexity only arises in that context as part of

a preliminary list of non-exclusive factors that the court must consider in deciding whether to

grant that continuance. See 3161(h)(7)(B)(ii)-(iv). Simply, the statute requires an examination

of complexity at the time and under the circumstances of the request then pending for a

continuance. The Court must assess, in the context of each discrete request for continuance,

[w]hether the case is so unusual or so complex, due to the number of defendants, the nature of

the prosecution, or the existence of novel questions of fact or law, that it is unreasonable to

expect adequate preparation for pretrial proceedings or for the trial itself within the time limits

established by this section. Here, the government did not rely on any novel legal or factual

question or anything unique regarding the nature of the case. The only factor at issue seems to

have been its decision to indict a large number of defendants. In any event, the first question

must be not whether the case is complex, but what continuance is it issue, so that the court

can assess how the potential complexity of the case figures into the time that would be excluded.

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 7 of 13

Until there is a specific continuance at issue, the complexity provision is not triggered, and there

is no language in the STA addressing what the Court did here, in making an advance carte

blanche determination that the case was, per se, complex for STA purposes. The STA requires

that a cases complexity be considered not as a general matter, but as one factor among

many in a circumstance-by-circumstance evaluation regarding a particular requested

continuance, for a particular purpose, over a specified period of time.

The Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit have issued multiple decisions to rein in and

discourage the overbroad use of the kinds of ends of justice findings employed in this case. In

Zedner, 547 U.S. at 507, the Supreme Court rejected passing reference to the cases

complexity as grounds for excluding time under the Act. And in United States v. Clymer, the

Ninth Circuit similarly warned against the kind of orders entered in this case:

We take this opportunity once again to emphasize that the ends of justice

exclusion in 3161(h)[] is not to be routinely applied, and that it may not be

invoked in such a way as to circumvent the time limitations set forth in the

Act. The Speedy Trial Act and its amendments are the product of a series of

delicate legislative compromises. [which] could be seriously distorted if a

district court were able to make a single, open-ended ends of justice

determination early in a case, which would exempt the entire case from the

requirements of the [STA] altogether.

25 F.3d 824, 829 (9th Cir. 1994) (citations omitted). Clymer came after United States v. Jordan,

where the Ninth Circuit reversed a district courts general order that the entire 33-defendant

case was complex and came within the ends of justice exclusion, thereby stopping the speedy

trial clock. 915 F.2d 563, 564 (9th Cir. 1990). In fact, Clymer cited Jordan to establish the wellmarked limit prohibiting the approach taken in this case. See also United States v. Lloyd, 125

F.3d 1263, 1268 (9th Cir. 1997). Here, as in Clymer, the district court made a general

complexity determination, as opposed to a complexity determination in the context of a request

for a specific and discrete continuance, leaving the matter impermissibly open-ended, coming

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 8 of 13

more than a month before the Court actually set a new trial date: Jordan and its predecessors

clearly prohibit this kind of open-ended declaration. Clymer, 25 F.3d at 828. The Courts March

9 order, excluding time provisionally and indicating that later it would find a further period of

excludable delay, without considering any of the relevant future facts and circumstances that

would support that additional delay, and also without seeing the governments additional status

reports and without the benefit of the parties proposals regarding a discovery schedule, the

parties anticipated pretrial motions, and the procedure and time needed for summonsing and

selecting the jury. [Doc. 289 at 5-6] But the Ninth Circuit plainly requires that, to comply with

the Speedy Trial Act, delay must be limited to a specific continuance, that is specifically

limited in time at the time the order is entered, and justified [on the record] with reference to

the facts as of the time the delay is ordered. Lloyd, 125 F.3d at 1268. The Court is prohibited

from referencing past ends of justice continuances as a basis for exclusions of time. To

summarize: [A]n ends of justice exclusion under [] 3161(b) is proper only if ordered for a

specific period of time and justified on the record with reference to the factors enumerated in []

3161(h)(8)(B), and any other approach is simply impermissible under the Speedy Trial Act.

Jordan, 915 F.2d at 566. And the law requires procedural strictness so that such rulings do not

get out of hand and subvert the Acts detailed scheme. Zedner, 547 U.S. at 509.

The Court must consider four factors: First, it must consider (1) [w]hether the failure to

grant such a continuance would be likely to make a continuation of such proceeding

impossible, or result in a miscarriage of justice; (2) [w]hether the case is so unusual or so

complex that it is unreasonable to expect adequate preparation for pretrial proceedings or for

the trial itself within the time limits established by the Act; (3) [w]hether the failure to grant

such a continuance in the proceeding, in a case which taken as a whole, is not so unusual or so

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 9 of 13

complex, and in that context, whether such failure would (a) deny the defendant reasonable

time to obtain counsel, (b) unreasonably deny the defendant or the Government continuity of

counsel, or (c) deny counsel for the defendant or the attorney for the Government the

reasonable time necessary for effective preparation, taking into account the exercise of due

diligence. 3161(h)(7)(B)(i)-(iv). In this case, the Court short-circuited that analysis, basing its

order on conclusory as opposed to specific statements applying the statutory factors.

Second, even if the factors weigh in favor of granting a continuance and excluding time

under the STA clock, the Court must specifically find that the ends of justice purportedly

served by the continuance outweigh the best interests of the public and the defendant in a

speedy trial. 3161(h)(7). While the Court recited this standard in its March 9 order, it never

documented a finding correctly applying it. [Doc. 289 at 5] And other orders regarding Mr.

Bundys STA rights made clear that it based its rulings in this case on factors outside the Act.

[See Doc. 846 at 7-9 (denying Mr. Bundys motion because of how it would cause severe

prejudice to court proceedings in two districts and to the many witnesses that the parties are

expected to call in this matter [and because] [g]ranting the Bundys requested continuance

would prejudice the District of Nevadas ability to manage its complex case in which Ammon

and Ryan Bundy are also charged.]

Third, the Court must set forth, either orally or in writing, the reasons for concluding that

the ends of justice served in granting the continuance outweigh the best interests of the public

and the defendant in a speedy trial. 3161(h)(7)(A). These findings must made express[ly],

and explicitly. Zedner, 547 U.S. at 506 ([T]he District Courts technical failure to make an

express finding is not excusable, and if a judge fails to make the requisite findings regarding

the need for an ends-of-justice continuance, the delay resulting from the continuance must be

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 10 of 13

counted, and if as a result the trial does not begin on time, the indictment or information must be

dismissed.). This is particularly true with a supposed complexity ruling, where the court must

explain, in detail, the relevance and nature of the discovery in support of its ruling. [The Act] is

not satisfied by the District Courts passing reference to the cases complexity and [t]herefore,

the continuance is not excluded from the [STA] clock. Zedner, 547 U.S. at 507. The Court

cannot make findings regarding the nature of the case or the relevance of discovery that

support a request to exclude time until that request is actually made. United States v. Toombs,

574 F.3d 1262, 1272 (10th Cir. 2009). In the present case, the government had not even

completed the initial phase of its discovery when the Court entered its order. So the Court could

only characterize the nature of the case and discovery in a manner that was necessarily general

admitting that it was without the benefit of the parties proposals regarding a discovery

schedule, the parties anticipated pretrial motions, and the procedure and time needed for

summonsing and selecting the jury. [Doc. 289 at 5] Later, the Court essentially conceded that its

conclusions with respect to the prospective complexity findings were unwarranted when it

denied Mr. Bundys request for a continuance on grounds that Mr. Bundy need not review any of

the governments discovery to prepare for trial. [Doc. 846 at 10]

Fourth, the Court must actually grant a continuance in the context of its complexity

order. See United States v. Doran, 882 F.2d 1511, 1517 (10th Cir. 1989) (The court did not

even explicitly grant a continuance.). Here, the Courts March 9 order did not grant a

continuance but, rather, merely vacated the trial date and ordered time excluded based on the

governments general request for a designation of this matter as complex. [Doc. 289 at 1-2]

II. THE COURTS DEMAND FOR DEFENDANTS WAIVER OF HIS STA RIGHTS WAS ERROR.

In this case, the Court prospectively granted the governments requests for delay

but refused to consider a defendants request until he waived his STA rights. See

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 11 of 13

6/15/2016 Hrg. at 29-30 ([D]efendants [who] waived their speedy trial rights

[have been] relieved from preparing for the September 7th trial [but] were going to

do everything we can to move forward [to trial] as to those defendants who have not

waived their [STA] rights.). Implementing such a policy is error. Regardless of how

presented, a defendant may not prospectively waive the application of the Act. Zedner,

547 U.S. at 500 (The purposes of the Act also cut against exclusion on the grounds of

mere consent or waiver.). [A] defendant cannot waive time under the [STA]. United

States v. Ramirez-Cortez, 213 F.3d 1149, 1156 (9th Cir. 2000). To permit a defendant to

waive his [STA] right[s] seriously undermine[s] our rule that the defendant cannot

prospectively consent to an STA violation. Alvarez-Perez, 629 F.3d at 1060.

III. THE 70-DAY STA CLOCK EXPIRED BY AT LEAST MONDAY, AUGUST 29, 2016.

Where the government does not bring a defendant to trial within the time limit required

by [] 3161(c) as extended by [] 3161(h), the indictment shall be dismissed. 3162(a)(2).

In calculating the STA clock as to Mr. Bundy, the Court must consider whether it is reasonable

to attribute to Mr. Bundy the exclusion or exclusions of time, i.e., delay that does not count

against the STA clock, resulting from the actions of his co-defendants. United States v. Messer,

197 F.3d 330, 338 (9th Cir. 1999) (reversing convictions and ordering that the indictment be

dismissed for violating the defendants STA rights). The Ninth Circuit has directed that such

determinations must be made on a case-by-case basis after reviewing the totality of the

circumstances prior to trial, including actual prejudice suffered by the imputation of the

exclusion to Mr. Bundy, Mr. Bundys adamancy in asserting his STA rights, whether Mr. Bundy

was in custody pre-trial, and any disconnect[] between the delay [at issue] and 3161(h)(7)s

purpose. Id. at 336-338 & n.8 (citing numerous cases). This reasonableness inquiry is factintensive, and whether the imputation of delay impairs a defendants ability to prepare for trial

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 12 of 13

or result[s] in excessive pretrial incarceration will weigh heavily in favor of dismissal. United

States v. Stephens, 489 F.3d 647, 654 (5th Cir. 2007); Messer, 197 F.3d at 340. Applying the

Ninth Circuits guidance, and taking into account the invalidity of the Courts complexity

order, the following periods of time (at a minimum) elapsed unexcluded on the 70-day STA

clock as applied to Mr. Bundy in this case: January 27-30 (Days 1-3), February 3-10 (Days 411), March 10-15 (Days 12-17), March 23-April 14 (Days 18-40), April 16-21 (Day 41-46), June

30-July 21 (Day 47-68), and August 25-29 (Day 69-73). The result is that the 70 days allowed by

the STA have expired and this case must be dismissed.

IV. THE GOVERNMENTS TACTICAL DELAY FURTHER JUSTIFIES DISMISSAL.

Because the government intentionally prejudiced Mr. Bundy in the delay, both before and

after indictment, the case should be dismissed under Fed. R. Crim. P. 48(b)(1) and 5th

Amendment. See United States v. Gouveia, 467 U.S. 180, 192 (1984) (Fifth Amendment

requires the dismissal if the defendant can prove that the Government's delay in bringing the

indictment was a deliberate device to gain an advantage over him and that it caused him actual

prejudice in presenting his defense.). The government has admitted that it intentionally delayed

taking action during the occupation for political reasons. [Docs. 1052, at 16; 1065 & 1068]

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, the 70-day limit established by the STA has been

exceeded, and the Court must dismiss the charges pending against Mr. Bundy. Because the

delays at issue are the direct result of the governments conduct, over Mr. Bundys objections,

and because of how the delay (both pre- and post-indictment) has prejudiced Mr. Bundys rights

and ability to prepare for a fair trial, the Court should dismiss with prejudice.

DATED: September 6, 2016

/s/ Marcus R. Mumford

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

10

Case 3:16-cr-00051-BR

Document 1203

Filed 09/07/16

Page 13 of 13

Marcus R. Mumford

J. Morgan Philpot

Attorneys for Ammon Bundy

MEMO IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS FOR IMPERMISSIBLE DELAY

11

You might also like

- Nevada OrderDocument27 pagesNevada OrderMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Barrow Response Dismiss IndictDocument7 pagesBarrow Response Dismiss IndictMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Marshals Mumford Probable CauseDocument1 pageMarshals Mumford Probable CauseMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Verdict Forms Returned in Oregon Standoff CaseDocument1 pageVerdict Forms Returned in Oregon Standoff CaseMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Jason Patrick Seeks Release Conditions ChangedDocument3 pagesJason Patrick Seeks Release Conditions ChangedMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Ethan Knight Status Report/ Feb. TrialDocument2 pagesEthan Knight Status Report/ Feb. TrialMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Lisa Ludwig Joint Status Report Re. Ryan BundyDocument2 pagesLisa Ludwig Joint Status Report Re. Ryan BundyMaxine Bernstein100% (1)

- Ammon Bundy and Co. Verdict FormsDocument1 pageAmmon Bundy and Co. Verdict FormsMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Initial Jury Note Before Juror 11 TossedDocument1 pageInitial Jury Note Before Juror 11 TossedMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Jury Notes, Judge ResponsesDocument3 pagesJury Notes, Judge ResponsesMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Verdict Forms For All 7 #Oregonstandoff DefendantsDocument8 pagesVerdict Forms For All 7 #Oregonstandoff DefendantsMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Ammon Bundy's Lawyer Seeks New 2nd Amend. Jury InstructionsDocument2 pagesAmmon Bundy's Lawyer Seeks New 2nd Amend. Jury InstructionsMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Governor's Office Email Jan. 15Document9 pagesGovernor's Office Email Jan. 15Maxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Shawna Cox Latest FilingDocument7 pagesShawna Cox Latest FilingMaxine Bernstein0% (1)

- Bundy Motion To Dismiss JurorDocument11 pagesBundy Motion To Dismiss JurorMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- ABundy'ssoughtexhibitsDocument56 pagesABundy'ssoughtexhibitsMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Govt's Sentencing Memo For Brian CavalierDocument3 pagesGovt's Sentencing Memo For Brian CavalierMaxine Bernstein100% (1)

- Who Is John KillmanDocument5 pagesWho Is John KillmanMaxine Bernstein100% (1)

- Wampler Seeking This Testimony in His DefenseDocument6 pagesWampler Seeking This Testimony in His DefenseMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Outline of Govt S Rebuttal Expected TodayDocument2 pagesOutline of Govt S Rebuttal Expected TodayMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Rusty Hammond DeclarationDocument2 pagesRusty Hammond DeclarationMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Mumford S Objections Govt RebuttalDocument8 pagesMumford S Objections Govt RebuttalMaxine Bernstein100% (1)

- Bundy Wants Govt To ID InformantsDocument5 pagesBundy Wants Govt To ID InformantsMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Judge Written Ruling Dismiss CT 2 CoxDocument5 pagesJudge Written Ruling Dismiss CT 2 CoxMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- AMjuryinstructionchanges PDFDocument2 pagesAMjuryinstructionchanges PDFMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Govt Response Cox Count 2Document2 pagesGovt Response Cox Count 2Maxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- AMjuryinstructionchanges PDFDocument2 pagesAMjuryinstructionchanges PDFMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Anonymous Bar Complaint Against Matthew SchindlerDocument2 pagesAnonymous Bar Complaint Against Matthew SchindlerMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Judge Jones On Bundy AccommodationsDocument2 pagesJudge Jones On Bundy AccommodationsMaxine BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Judge Denies Ryan Bundy's Motion For MistrialDocument3 pagesJudge Denies Ryan Bundy's Motion For MistrialMaxine Bernstein100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Book Review-ClassicsDocument2 pagesBook Review-Classicsapi-2455489570% (1)

- Paritala RaviDocument7 pagesParitala Ravibhaskarchow100% (4)

- Evidence Final ExamDocument2 pagesEvidence Final ExamHadji HrothgarNo ratings yet

- United States v. Daryls Foster Steed, 646 F.2d 136, 4th Cir. (1981)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Daryls Foster Steed, 646 F.2d 136, 4th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

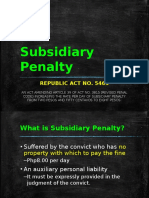

- Subsidiary PenaltyDocument13 pagesSubsidiary PenaltyJezen Esther Pati100% (2)

- Shahnaz Filed IndictmentDocument7 pagesShahnaz Filed IndictmentNewsdayNo ratings yet

- Summary of Chapter13 of Leaves From My Personal Life by V.r.krishna IyerDocument2 pagesSummary of Chapter13 of Leaves From My Personal Life by V.r.krishna IyerUjvalMittal33% (3)

- The Prosecution of Impiety in Athenian LawDocument7 pagesThe Prosecution of Impiety in Athenian LawNicolas Vejar GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Position Paper - Death PenaltyDocument3 pagesPosition Paper - Death PenaltyJaydeeNo ratings yet

- Turquesa v. ValeraDocument3 pagesTurquesa v. ValeraAlex RabanesNo ratings yet

- People Vs GomezDocument8 pagesPeople Vs GomezKristine DyNo ratings yet

- United States v. Vaughn J. Curtis, A/K/A Vaughn Mark Bruno, A/K/A Twin, 14 F.3d 597, 4th Cir. (1994)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Vaughn J. Curtis, A/K/A Vaughn Mark Bruno, A/K/A Twin, 14 F.3d 597, 4th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Manalo VS, SistozaDocument8 pagesManalo VS, SistozaJu LanNo ratings yet

- Drug CasesDocument9 pagesDrug CaseselCrisNo ratings yet

- Chillicothe Police Reports For April 11th, 2013Document26 pagesChillicothe Police Reports For April 11th, 2013Andrew AB BurgoonNo ratings yet

- Motion To Fix BailDocument3 pagesMotion To Fix BailJaps Alegre50% (4)

- Security Guard Functions DutiesDocument2 pagesSecurity Guard Functions DutiesMaulik Yogesh Thakkar100% (2)

- PNP organizational structureDocument5 pagesPNP organizational structureHarla Jane Ramos FlojoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court upholds conviction of man for killing pregnant wifeDocument7 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court upholds conviction of man for killing pregnant wifeCatherine MerillenoNo ratings yet

- Nirma University: Institute of LawDocument21 pagesNirma University: Institute of LawABHISHEK SAAD100% (1)

- Trespass To Person IDocument6 pagesTrespass To Person IamilahudaNo ratings yet

- The Economic Security of Business Transactions: Management in BusinessDocument462 pagesThe Economic Security of Business Transactions: Management in BusinessChartridge Books OxfordNo ratings yet

- Jadewell V Lidua DigestDocument2 pagesJadewell V Lidua DigestClarisse89% (9)

- Durban Apartments liable for stolen carDocument6 pagesDurban Apartments liable for stolen carLexa L. DotyalNo ratings yet

- SPL Digest CasesDocument10 pagesSPL Digest CasesNombs NomNo ratings yet

- RTC Branch 87 Answer Denies Plaintiff's ClaimsDocument6 pagesRTC Branch 87 Answer Denies Plaintiff's ClaimsConcepcion CejanoNo ratings yet

- Kia v. INS, 4th Cir. (1999)Document3 pagesKia v. INS, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Plea BargainDocument4 pagesPlea BargainAw LapuzNo ratings yet

- VAWC FormsDocument4 pagesVAWC Formsjohn dexter abiertasNo ratings yet