Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Washington D.C

Uploaded by

Parul VyasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Washington D.C

Uploaded by

Parul VyasCopyright:

Available Formats

8/3/2016

Washington D.C. and Beyond

The 1901 Plan for Washington D.C. was the first expression of the City Beautiful movement in the United States,

influencing the emerging profession of city planning and the subsequent beautification projects in Chicago,

Cleveland, and San Francisco, among other cities. Building on the core of government and monumental buildings,

supervised by the Commission of Fine Arts headed by Burnham and Olmsted, was interrupted during WWI, and

resumed in the 1920s. The initial plan was completed in May1922 with the erection of the Lincoln Monument.

Reaction to the plan, from the beginning, was mixed. Middle class residents of Washington D.C. were glad to be

rid of the railroad tracks on the Mall, considered a park for city residents before the 1901 plan, but were

concerned with the price tag and "fears of its excessive formalism were still being voiced as late as 1910."

(Gutheim, 36) On a purely cultural and aesthetic level, critics were quick both to praise and criticize the use of

the European Beaux-Arts idiom. Montgomery Schuyler, a noted architectural critic, enthused in May 1902, "We

can have nothing but praise for the magnificent scheme of Messrs. Burnham, McKim, Olmsted, and St.

Gaudens. Their part in the making of a beautiful city has been so well done that they already deserve to be

ranked with L'Enfant in the gratitude of Washingtonians and of all Americans who wish to be justified of their

pride in the capital." (qtd. in Craig, 254). Yet the WashingtonEvening Star held quite a different opinion two

years later: "It was a sad day for the city of Washington and all the people of the country interested in the welfare

of the National Capital when Charles F. McKim was sent to be educated at the Ecole des Beaux Arts." (qtd. in

Craig, 254)

In general, the goals of the Commissioners were met in the

implementation of the 1901 Plan. They succeeded in providing a

national sacred space, an area on which the nation could focus its

pride and point to as its cultural authority and heritage, drawing on

the classical forms which gesture to Athenian democracy and the

founding fathers. They succeeded in legitimizing their own place in

the social structure, demonstrating the power they possessed and

their usefulness to society. They succeeded in legitimizing a growing governmental structure through the symbolic

relationships (the North-South and East-West axes of which the Capitol, the White House, and the Washington

Monument are the foci) and the sacralization of their placement in the monumental core. And they succeeded in

setting a standard for urban beautification.

Yet in many ways the plan did not live up to the expectations of the Commissioners or the public. The

opportunity to rectify an omission in L'Enfant's plan--providing an appropriate space for the Supreme Court in

the Mall's axis of power--was missed. Instead, the Commission planned a Supreme Court building in the Capitol

grounds complex, to balance the group with a monumental structure paralleling Burnham's Union Station.

Further, the emphasis on the core of monumental and government buildings was an exclusive, rather than

inclusive, construction. "Government buildings designed to complement the neoclassicism of Jefferson's and

L'Enfant's era were to line the Mall and encircle Capitol Hill and the White House...tending to seal off official

Washington from the neighboring commercial and residential districts." (Hines, 92)

However, the most important element that did not seem to succeed in the plan was the amorphous goal of civic

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~cap/CITYBEAUTIFUL/dc.html

1/2

8/3/2016

Washington D.C. and Beyond

idealism leading to moral and economic improvement. The center of the city had been beautified and became a

focus for national pride. Yet the impoverished living in the shadow of the Capitol's dome were not necessarily

inspired with civic loyalty, and were certainly no better off economically for the expensive monumental plan.

Boyer points out that effective "socialization through the civic ideal was an

unproveable proposition at best, tenuous or nebulous at worst." (90) How could the

urban poor, the largest population in Washington's city center, be "made to realize

their abstract obligation to promote the 'ethical well-being of the whole community'

when their individual preoccupations were so much more tangible and compelling?"

(254) The idea that the poor would be somehow morally rejuvenated, and therefore

more apt to succeed economically, through proximity to a beautiful city center was

unproven and unproveable. Ultimately, in the 1901 plan for Washington D.C., the

City Beautiful movement was unsuccessful only in the one thing it expressly allied

itself with--Progressive moral and economic reform in the urban center.

The legacy of the 1901 Plan is still felt throughout the United States. The profession of city planners is well

established, the prominence of the Mall in national pride is unquestioned, and the legitimacy of government as

expressed in Beaux-Arts style can be found in every state. The debate over the role of city beautification versus

economic redevelopment still rages, and in Washington D.C., the aims and uses of the Plan of 1901 are being

renegotiated. Architect Kent Cooper recently wrote, "Our foremost problem is not the placement of new

monuments and museums. They can wait. Rather, the issue for today is how best to restore the balance of fiscal

resources, economic opportunity, and social and racial diversity across the spectrum of the metropolitan area so

that all may prosper and the monumental core will not strangle." As Washington D.C. nears its bicentennial, the

problems the 1901 Plan set out to solve are still with us.

The City Beautiful ~ The 1901 Plan ~ Washington D.C. and Beyond ~ Notes and Further Reading ~ Home

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~cap/CITYBEAUTIFUL/dc.html

2/2

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Stage DesignDocument96 pagesStage DesignParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- House & Garden - November 2015 AUDocument228 pagesHouse & Garden - November 2015 AUHussain Elarabi100% (3)

- SCIENCE 5 PPT Q3 W6 - Parts of An Electric CircuitDocument24 pagesSCIENCE 5 PPT Q3 W6 - Parts of An Electric CircuitDexter Sagarino100% (1)

- BVOP-Ultimate Guide Business Value Oriented Portfolio Management - Project Manager (BVOPM) PDFDocument58 pagesBVOP-Ultimate Guide Business Value Oriented Portfolio Management - Project Manager (BVOPM) PDFAlexandre Ayeh0% (1)

- World War 2 Soldier Stories - Ryan JenkinsDocument72 pagesWorld War 2 Soldier Stories - Ryan JenkinsTaharNo ratings yet

- Shahin CVDocument2 pagesShahin CVLubainur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Development's Evaluation in Public ManagementDocument9 pagesHuman Resource Development's Evaluation in Public ManagementKelas KP LAN 2018No ratings yet

- Dte ArchiveDocument20 pagesDte ArchiveParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Downtoearth: Climate Change Poses A Powerful Challenge To The Idea of FreedomDocument60 pagesDowntoearth: Climate Change Poses A Powerful Challenge To The Idea of FreedomParul VyasNo ratings yet

- LS01 - Culture in Vernacular Architecture - WorksheetDocument18 pagesLS01 - Culture in Vernacular Architecture - WorksheetParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Gobar Times: Chew On ThisDocument20 pagesGobar Times: Chew On ThisParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Ind 1Document2 pagesInd 1Parul VyasNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Ahmadabad PDFDocument5 pagesGujarat Ahmadabad PDFParul VyasNo ratings yet

- 0.56859500 1457688308 PreviewDocument10 pages0.56859500 1457688308 PreviewAnonymous 8zD3BRayRDNo ratings yet

- UD100 Lo ResDocument49 pagesUD100 Lo ResParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Downtoearth: Climate Change Poses A Powerful Challenge To The Idea of FreedomDocument60 pagesDowntoearth: Climate Change Poses A Powerful Challenge To The Idea of FreedomParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Ind 2Document2 pagesInd 2Parul VyasNo ratings yet

- Ind 3Document2 pagesInd 3Parul VyasNo ratings yet

- Villa RadieuseDocument6 pagesVilla RadieuseLígia MauáNo ratings yet

- Important To ReadDocument7 pagesImportant To ReadParul VyasNo ratings yet

- New Urbanisms: From Neo-Traditional Neighbourhoods To New RegionalismDocument11 pagesNew Urbanisms: From Neo-Traditional Neighbourhoods To New RegionalismParul VyasNo ratings yet

- 165Document35 pages165Parul VyasNo ratings yet

- Jarash Case Study2Document33 pagesJarash Case Study2Parul VyasNo ratings yet

- The 1901 Plan For Washington DDocument4 pagesThe 1901 Plan For Washington DParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Scene Design and Stage Lighting - The Eighteenth CenturyDocument1 pageScene Design and Stage Lighting - The Eighteenth CenturyParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Scene Design and Stage Lighting - Ancient RomeDocument1 pageScene Design and Stage Lighting - Ancient RomeParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Scene Design and Stage Lighting - The Twentieth CenturyDocument1 pageScene Design and Stage Lighting - The Twentieth CenturyParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Scene Design and Stage Lighting - Ancient GreeceDocument1 pageScene Design and Stage Lighting - Ancient GreeceParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Stage Lighting Revealed A Design and Execution Handbook PDFDocument30 pagesStage Lighting Revealed A Design and Execution Handbook PDFParul VyasNo ratings yet

- Revitalizing Urban Life in Historic KermanshahDocument12 pagesRevitalizing Urban Life in Historic KermanshahParul Vyas100% (1)

- PLN Local Dev Design Urban CharacterisationDocument171 pagesPLN Local Dev Design Urban CharacterisationParul VyasNo ratings yet

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsDocument11 pages01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoNo ratings yet

- Portfolio ValuationDocument1 pagePortfolio ValuationAnkit ThakreNo ratings yet

- Adorno - Questions On Intellectual EmigrationDocument6 pagesAdorno - Questions On Intellectual EmigrationjimmyroseNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Maam MyleenDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Maam MyleenRochelle RevadeneraNo ratings yet

- CV Finance GraduateDocument3 pagesCV Finance GraduateKhalid SalimNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 (New) Medication History InterviewDocument6 pagesLesson 6 (New) Medication History InterviewVincent Joshua TriboNo ratings yet

- ESSAYSDocument5 pagesESSAYSDGM RegistrarNo ratings yet

- Adam Smith Abso Theory - PDF Swati AgarwalDocument3 pagesAdam Smith Abso Theory - PDF Swati AgarwalSagarNo ratings yet

- Hidaat Alem The Medical Rights and Reform Act of 2009 University of Maryland University CollegeDocument12 pagesHidaat Alem The Medical Rights and Reform Act of 2009 University of Maryland University Collegepy007No ratings yet

- A COIN FOR A BETTER WILDLIFEDocument8 pagesA COIN FOR A BETTER WILDLIFEDragomir DanielNo ratings yet

- The Butterfly Effect movie review and favorite scenesDocument3 pagesThe Butterfly Effect movie review and favorite scenesMax Craiven Rulz LeonNo ratings yet

- Senarai Syarikat Berdaftar MidesDocument6 pagesSenarai Syarikat Berdaftar Midesmohd zulhazreen bin mohd nasirNo ratings yet

- Executive Support SystemDocument12 pagesExecutive Support SystemSachin Kumar Bassi100% (2)

- It ThesisDocument59 pagesIt Thesisroneldayo62100% (2)

- Understanding Abdominal TraumaDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Abdominal TraumaArmin NiebresNo ratings yet

- Hand Infection Guide: Felons to Flexor TenosynovitisDocument68 pagesHand Infection Guide: Felons to Flexor TenosynovitisSuren VishvanathNo ratings yet

- jvc_kd-av7000_kd-av7001_kd-av7005_kd-av7008_kv-mav7001_kv-mav7002-ma101-Document159 pagesjvc_kd-av7000_kd-av7001_kd-av7005_kd-av7008_kv-mav7001_kv-mav7002-ma101-strelectronicsNo ratings yet

- Dealer DirectoryDocument83 pagesDealer DirectorySportivoNo ratings yet

- Dr. Xavier - MIDocument6 pagesDr. Xavier - MIKannamundayil BakesNo ratings yet

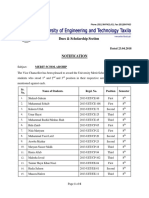

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocument6 pagesDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNo ratings yet

- BMW E9x Code ListDocument2 pagesBMW E9x Code ListTomasz FlisNo ratings yet

- Absenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAbsenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature Reviewapi-349927558No ratings yet

- INDEX OF 3D PRINTED CONCRETE RESEARCH DOCUMENTDocument15 pagesINDEX OF 3D PRINTED CONCRETE RESEARCH DOCUMENTAkhwari W. PamungkasjatiNo ratings yet

- Hydrocarbon LawDocument48 pagesHydrocarbon LawParavicoNo ratings yet