Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cooperation & Competition During The Resort of Lifecycle Butler&Weidenfeld 2012

Uploaded by

shinkoicagmailcomOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cooperation & Competition During The Resort of Lifecycle Butler&Weidenfeld 2012

Uploaded by

shinkoicagmailcomCopyright:

Available Formats

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271724498

Cooperation and Competition During the Resort

Lifecycle

Article January 2015

DOI: 10.1080/02508281.2012.11081684

READS

154

2 authors:

Richard W. Butler

Adi Weidenfeld

University of Strathclyde

Middlesex University, UK

85 PUBLICATIONS 4,046 CITATIONS

12 PUBLICATIONS 166 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate,

letting you access and read them immediately.

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Adi Weidenfeld

Retrieved on: 21 April 2016

TOURISM RECREATION RESEARCH VOL. 37(1), 2012: 15-26

Cooperation and Competition During the Resort Lifecycle

RICHARD BUTLER and ADI WEIDENFELD

Abstract: The Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model has been used on numerous occasions and situations to

describe the destination development process but has rarely been used to explore more sophisticated and causal

relationships between the development stages and other aspects of working relationships including cooperation and

competition between tourism businesses in destinations. These relationships are influenced by the spatial proximity

between individual firms at the local scale and agglomeration of tourism firms at the regional scale. Drawing on the

knowledge of working relationships between tourism firms, this paper suggests an underlying conceptual framework

for the study of the dynamic nature of the cooperation, competition, and spatial proximity between tourism firms and

the interrelationships between these aspects throughout the TALC.

Keywords: competition; cooperation; spatial proximity; agglomeration; TALC.

Introduction

The tourism area lifecycle model (Butler 1980) is one of

the most frequently cited conceptual models related to

tourism destination development, and despite the length of

time since its initial publication, is still being utilised in

contemporary research (e.g., Garay and Cnoves 2011). The

original model was focused on describing the process of

development through which tourism destinations proceeded

and did not explore in detail any causal relationships

between stages of development and processes such as

competition or cooperation between individual enterprises

or destinations. It did deal briefly with some spatial

implications, particularly with respect to the location of

subsequent proximal destinations, but not with aspects such

as proximity of businesses within a destination. The model

was particularly concerned with the development of

destinations rather than with tourism enterprises within

such destinations, yet it is reasonable to argue that just as

destinations as entities are dynamic and change over their

development cycle, so too could individual enterprises and

the relationships between these be expected to change

throughout that cycle.

The impact of spatial proximity and agglomeration

between tourism businesses on cooperation in tourism has

been studied particularly in the context of tourism clusters

(Brown and Geddes 2007; Erkus-ztrk 2009; Hall 2004;

Jackson and Murphy 2002; Michael 2003; Michael and Hall

2007; Mitchell and Schreiber 2007; Nordin 2003; Weidenfeld

et al. 2011), while other studies (Baum and Mezias 1992;

Tsang and Yip 2009) have addressed the impact of these

spatial parameters on competition between enterprises. In a

related vein, the original model of the TALC (Butler 1980)

was an attempt to describe the creation and evolution of

such tourism clusters or destinations and the physical,

environmental, social and economic changes that accrue

along the cycle. The TALC has been also applied to evaluate

networks, inter-organisation arrangements and their

dynamics in tourism destinations along different stages of

the development (Caffyn 2000; Zehrer and Raich 2010) but

without addressing the interrelationships between

cooperation and competition at different spatial scales. The

overall relationships between cooperation, competition, the

spatiality of tourism destinations in general, and

agglomeration of tourism firms over the development cycle

of destinations have been largely ignored, and it is this aspect

which is the specific focus of this paper.

The paper begins with a short review of the tourism

literature relating to cooperation, competition and coopetition between businesses, followed by a brief discussion

of the potential significance of the relative proximity or

density of businesses with respect to cooperation or

competition between businesses. Following this a conceptual

model is illustrated and discussed which illustrates the

potential behaviour, spatial proximity between and

agglomeration of tourism businesses with the stages of

destination development described in the TALC model.

Finally the implications for future research on the model are

discussed. Spatial clusters are constituted at different scales,

RICHARD BUTLER is Professor Emeritus at the Strathclyde Business School, 199 Cathedral Street, Glasgow G4 0QU, Scotland, UK.

e-mail: richard.butler@strath.ac.uk

ADI WEIDENFELD is a Marie Curie postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Marketing, Hanken Schhool of Economics, Vaasa, Finland.

e-mail: aweidenf@hanken.fi

Copyright 2012 Tourism Recreation Research

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

ranging from the local neighbourhood through the subregional and regional, to the national and international

levels (Malmberg and Maskell 2002). In this paper, the

difference between the local and the regional scale needs to

be clarified; spatial proximity is taken as the geographic

distance between individual businesses at the local scale

while agglomeration is the ratio between the number of firms

and the geographic 'size' of a particular area at the regional

scale. Local scale refers to working relations (i.e., cooperation,

competition or co-opetition) between individual

neighbouring intra-cluster Small and Medium Size Tourism

Enterprises (SMTES) and regional scale refers to working

relations amongst several SMTEs at a larger geographic

scale, characterised by forming groups or associations aimed

at achieving external economies of scale at the regional scale.

Therefore, a working relationship at the local scale refers to

between individual tourism businesses within the same

destination region.

Cooperation, Competition and Coopetition

Cooperation

Cooperation is recognised as an important determinant

of the success and competitiveness of a tourism destination

(Baggio 2011) and research has mainly focused on the

marketing of a tourism product as a bundle of services

including accommodation, attractions, and transportation,

which are often purchased and assessed by consumers as a

service value chain (Fyall et al. 2001; Grngsj 2003; Michael

and Hall 2007; Zehrer and Raich 2010). Motivation for

cooperation lies in the recognition by a firm of the potential

to generate external economies of scale, reduce risks and

overcome the growth of complexity, fragmentation and

turbulence as tourism develops in an area (Fyall and Garrod

2005; Weidenfeld et al. 2011; Zehrer and Raich 2010).

Cooperation is perceived as a way to increase businesses'

competitive position, including incorporating measures to

improve productivity, new product development, building

relationships with local suppliers, cooperation with similar

businesses, participating in local tourism destinations (Lade

2010). In some cases, when entry barriers are difficult and

present an obstruction to a large number of small companies,

these might form a cabal to fix prices and eliminate

competition (Shaw and Williams 2004).

Cooperation in tourism can involve the development

of both informal and formal inter-organisational

collaborative mechanisms, including partnerships

(Bramwell and Lane, 2000; Hall and Page 1999), networks

(Baggio and Cooper 2010; Morrison and Mill 1992; Saxena

2005; Zehrer and Raich 2010), consortia and alliances

(Garnham 1996), to deliver the tourism product (Baggio and

16

Cooper 2010; Fyall and Garrod 2005). At the regional scale,

it is strongly influenced by strong local leadership who

coordinate of activities and encourage cooperative processes,

particularly with supporting and related industries (Lade

2010). Wang and Krakover (2008) suggest four forms of

business relationships to describe cooperative working

relationships among tourism businesses in a destination:

affiliation, coordination, collaboration, and strategic

networks, in a continuum defined by various degrees of

formalization, integration and structural complexity required

by the nature and mission of marketing projects as the

destination develops. When the continuum of the cooperative

marketing relationship moves from affiliation to strategic

network, it may also move from a low degree to a high degree

of organizational integration which requires a more formal

and complex relationship with each other (Wang and

Krakover 2008). However, a high degree of organizational

integration does not necessarily indicate a similar degree of

cooperation in terms of trust and interdependencies; e.g. two

businesses can have a low degree of organizational

integration, but close and trustworthy informal cooperative

relationships, and it could be argued that this will vary with

the development stages of the TALC.

Competition and Coopetition

Competition in tourism is primarily for the time and

money of the customers, as firms tend to be engaged in

horizontal and vertical product differentiation and compete

to increase their profit margin by maximising their final price

as well as their share of their total generated margin through

increasing their market share, cost reductions and pricing

(Buhalis 2006; Papatheodorou 2004). Tourism businesses

try to maximize their own interests and do not participate in

collective actions when different self-interests lead to

businesses competing against each other to best fulfil their

own self-interests (Wang and Krakover 2008). Their ability

to compete depends on the interaction of three elements:

market competition (competing for the same tourist profile),

development or adjustment of their products or production

processes (innovations) and existing forms of production

(competition between similar products) (Ioannides and

Petersen 2003).

A framework for studying competition among tourism

destinations (Buhalis 2006) and between organisations at

various spatial and organisational scales suggests five levels

and provides a useful but generalised framework for

studying competition between destinations. This scheme

refers to places and regions as based on pre-existing 'natural

and socio-cultural resources', and thus includes a spatial

aspect, which is not related to the spatiotemporal aspects of

destination development stages. In reality, tourism

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

destinations and tourism organisations vary enormously in

size and spatial relationships and are far more complex than

implied by Buhalis (2006). Therefore, there is no reason that

this conceptualization would not be applicable to tourism

enterprises as implied below. Level one refers to competition

from proximal, similar product businesses and service

providers, for which businesses need to develop 'co-opetition'

(cooperative competition) strategies, whereby there is

cooperation and competition between individual businesses

and amongst groups of attractions at the destination regional

scale (Buhalis 2006). Cooperative competition or vertical and

horizontal 'co-petition' within destinations and within value

systems is increasingly important for the survival and

profitability of organisations sharing the same destiny, 'codestiny' (Buhalis 2006).

Competition from distant similar product businesses

(level two), drives regional cooperation amongst businesses

to establish their brand and develop collective differentiation;

it applies to competition from similar or undifferentiated

regions. Level three refers to competition in differentiated

regions with dissimilar product businesses, whose

distinctive natural and socio-cultural resources are not easily

substituted. Level four addresses competition with other

tourism businesses within the distribution channels, as each

member of the channel seeks enhanced profit margins and

level five relates to competition with recreational and leisure

facilities and activities, both at places of origin and in tourism

destinations. It would be reasonable to assume that the

relative importance of these levels is dynamic and responds

to and reflects the changing nature and level of development

of a destination, although this point is not pursued further

here.

Working Relations, Spatial Proximity and Agglomeration

There are indications that the spatial proximity between

tourism businesses at the local scale and the levels of

agglomeration among businesses at the regional scale

determine the working relations between tourism businesses

(Wang and Krakover 2008). It is clear that spatial proximity

and levels of agglomeration change throughout the TALC

as destinations grow and sometimes decline, and this paper

suggests that multiple and changing relations between

enterprises are influenced by these spatial factors.

Cooperation between tourism businesses at the local scale is

likely to involve more informal and personal relationships

and local initiatives e.g., joint investments in product

infrastructure (see Weidenfeld et al. 2011). At a larger

geographic scale, enterprises form groups or associations

aimed at achieving external economies of scale in order to

compete with other destination regions, and may involve

formal agreements and joint collaboration initiatives e.g.

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

marketing groups and policy formation.

In Weidenfeld et al (2011)'s study on cooperation

among tourism attractions, at a particular point in time,

spatial proximity and agglomeration are shown to be

positively related to cooperation at both the local scale and

regional scale. However, in less-agglomerated destinations,

regional cooperation in marketing and regional competition

for markets is higher (Wang and Krakover 2008). Other

inextricably linked influential features of SMTEs, including

product type, visit duration, market segments' type/size,

group size, frequency and durability of firm interactions

(Huybers and Bennett 2003; Weidenfeld et al. 2011) also

determine cooperation between tourism firms and clearly

can be expected to change over time. Tourism firms are likely

to compete more for local markets at the local scale, and less

for distant markets at the regional scale, as tourism

businesses tend to collaborate in joint marketing campaigns

in order to attract tourists to the destination and compete

with other destinations (Wang and Krakover 2008).

Agglomeration Economies and Tourism Clusters

Inherited local or regional resources create a

comparative advantage, particularly where there are

deficiencies in alternative/rival activities (Gordon and

Goodall 2000). When external economies of scale are a result

of co-location and are benefits a firm derives from being

located close to other economic actors, and caused by factors

beyond the actions or responsibilities of a firm, they are called

agglomeration economies, positive spatial spillovers, or thick

market effects, which generate more efficient or cost effective

production processes (Cohen and Morrison 2005; Neffke et

al. 2011). Each of the following agglomeration economies

carries positive and negative agglomeration externalities,

which may change throughout the lifecycle of a destination

along with lower or higher levels of agglomeration of tourism

businesses and have implications for the survival and

sustainability of tourism businesses along the TALC.

Transport, Infrastructure, Specialised Inputs and Services

Concentration of tourism attractions, activities and

complementarities between them encourage agglomeration

of tourism businesses and related businesses (Gordon and

Goodall 2000). Positive externalities of this aspect include

lower transport and freight of both inputs and outputs, cost

savings and various types of thick market effects, which are

solely and directly attributed to the physical dimension of

spatial agglomeration (Cohen and Morrison 2005; Gordon

and McCann 2000). Tourism demand and subsequent

development in a destination depend on both long and short

distance access networks and a transport system, particularly

17

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

airport facilities (Clav 2007; Gordon and Goodall 2000) as

well as travel among businesses and between these and

services within destinations (Swarbrooke 2002). Transport

may generate opposite tendencies in spatial clusters; for

example, the development of different modes of transport

can facilitate concentration or accelerate dispersal across

tourism spaces (Shaw and Williams 2004; Masson and Petiot

2009). This can lead to some negative externalities such as

congestion, degradation and rising land prices.

A Local Pool of Workers and Flexible, Specialised and Mobile

Labour

A pool of labour is a pooled market for workers with

industry-specific skills, ensuring both a lower probability of

unemployment and of labour shortage (Krugman 1991) and

generally develops over time in specific locations. Every

agglomeration economy can have a pool of labour, especially

skilled workers, in a system which maximises the jobmatching opportunities between the individual worker and

the individual firm and minimises the search costs for both

(Gordon and McCann 2000). A pool of labour is

advantageous in overcoming seasonality, encouraging

innovations and information spillovers, as well as in

developing specialised niche products for niche markets

employing specialised labour, but also might lead to the

poaching of workers between businesses and to rising wages.

In the absence of a large pool of labour, businesses may find

more permanent long-term loyal workers but fail to benefit

from knowledge spillovers, innovations, specialised skills

and overcoming barriers to seasonality. A direct implication

of this aspect is a flexible division of labour between firms

within clusters, which also can be expected to change over

the development period. Flexible division or a fragmented

division of labour is characterised by a workers' and firms'

choice in selecting their workplace and workers (Hjalager

2000; Jackson and Murphy 2002; Shaw and Williams 2002)

and inter-firm necessary transactions in the production

process (Storper 2000).

This flexibility in the tourism and leisure labour

markets is attributed to both permanent and temporary (or

secondary) workers where the formalisation of dual labour

markets within companies occurs and " stems from the

particular nature of the demand for tourism and leisure

services" (Shaw and Williams 2002: 174). A flexible pool of

labour, particularly in case of seasonal workers like students

and immigrants, can encourage businesses such as hotels to

co-locate and incorporate with educational institutions

offering courses in tourism and hospitality in an attempt to

overcome labour shortage in high seasons (Hjalager 2000).

Such cooperation can also underlie other flexibilities such

as work time, wage and procedural (Rimmer and Zappala

18

1988 cited by Shaw and Williams 2004). Therefore, it is

assumed that businesses at high levels of agglomeration face

less difficulty in overcoming seasonality and temporal

variations in demand (e.g., weekday versus weekend,

unexpected peaks), common problems in tourism

destinations, but more poaching and high labour turnover

than those at lower agglomeration levels. More functional

and temporal flexibility in skilled workers and numerical

flexibility in semi- and un-skilled workers result in higher

competition for skilled labour but reduced competition for

unskilled labour. By contrast, low-agglomerated businesses

would enjoy a labour market dependency on a few employers

resulting in lower pressure on wages and lower turnover,

but would have less flexibility in labour and less selection of

skilled/unskilled workforce.

Diffusion of Knowledge, Innovations and Technology

Knowledge has a variety of overlapping forms (for

example, aesthetic, cognitive, scientific, discursive, digital,

information, tacit, explicit, emancipatory, embrained,

embodied, encultured, embedded and encoded) and is central

to the operation of contemporary advanced economies (Hall

and Williams 2008; Henry and Pinch 2000; Williams 2006).

In general, to create competitive advantage, there are always

strong systemic pressures to find 'new' ways of producing

'old' commodities, making existing products that reduce

costs by cutting the labour time needed in production

(Hudson 2005). The advantages of agglomeration could

entail more innovative production helping to sustain the

regional destination appeal, but greater similarity in the

production and less distinctiveness of the product as a result

of imitation between neighbouring firms can be

disadvantageous as well. This could result in more local

competition. At low levels of agglomeration, less diffusion

of innovation and the absence of change might decrease

tourism appeal and draw fewer tourists as products become

obsolete and vulnerable to competition as suggested in the

original TALC paper (Butler 1980). The outcome might be

higher levels of regional competition and cooperation.

Agglomeration Economies and Working Relationships

between SMTEs

High levels of agglomeration of businesses and services

are expected to allow more complementary relationships to

develop, and cost efficiency, and increase levels of local

cooperation. The abundance of service providers might

reduce costs and result in less collaboration amongst actors,

and the large number of tourists might decrease the need for

regional competition for tourists. Conversely, low

agglomerated businesses are less-accessible to tourists with

fewer opportunities for complementarities and variety in the

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

tourism production chain. However, they can also gain from

less-intense provision of services, infrastructure and

transport thus sustaining a clean, natural and exclusive

environment and enjoy a more monopolistic and stable

business local environment with less local competition and

sustaining exclusiveness of their tourism products. By

contrast, cooperation and competition for tourists at the

regional scale are likely to be higher.

The relationships between agglomeration and local

and regional cooperation and competition for tourists can

be summarised as follows: High levels of agglomeration are

negatively related to competition between tourism firms for

infrastructure, services and labour but not necessarily for

skilled labour. By contrast, low levels of agglomeration are

likely to be positively related to regional competition and

cooperation for tourists as well as regional cooperation on

the basis of reducing costs and buying services. Higher levels

of agglomeration mean greater availability of more mobile

labour and enhanced public transport and accessibility for

tourists and labour, which eases local competition for labour

and regional competition for markets (Weidenfeld et al. 2011).

They are also likely to engender more knowledge transfer

and learning between firms and therefore innovation than

at lower levels of agglomeration. Forces counteracting the

economies of scale deriving from agglomeration include

congestion or greater input competition in high-density areas

which could cause firms to locate in less-congested areas

(Bale 1976; Butler 2006; Cohen and Morrison 2005). Negative

spillovers or externalities, such as rising land and wage

prices, environmental degradation, congestion, corrosive

competition and diseconomies of scale, particularly for small

firms (Cohen and Morrison 2005; Newlands 2003; Raco

1999) were all features noted in the earliest discussions of

the TALC and suggested as causes of redevelopment of

tourism in neighbouring undeveloped locations (Butler

2006).

Tourism Destination Clusters

The co-location of firms and agglomeration economies

is a necessary condition for effective clustering to occur.

However, the mere co-location of firms does not guarantee

the process of optimising gains from economies of-scale and

of-scope, i.e. gains attributed to the cluster's formation

captured as a result of reductions in the average costs of the

member firms, which is the rationale for clustering. Rather,

it is a process in the form of a continuum, by which firms

enhance their ability to cooperate. Clustering produces a

range of synergies which may enhance the growth of market

size, employment and product (Michael 2007). The definition

of a cluster can be used also to describe a destination

with its conglomeration of competing and collaborating

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

businesses, generally working together in associations and

through partnership marketing to put their location on the

map (Jackson and Murphy 2006: 1022). The definition of a

tourism cluster in this paper is an array of linked industries

and other entities in competition, which provide

complementary products and services as a holistic tourism

experience such as accommodation, attractions and retail

outlets (Wang and Fesenmaier 2007). These businesses

represent a range of different types of enterprise, meaning

that each has its own agenda and priorities (Jackson and

Murphy 2002).

The co-location of tourism businesses does not only

increase agglomeration economies, but also the process of

optimising gains from economies of-scale and of-scope as a

result of reductions in the average costs of constituent firms.

These may result in production linkages, which can be

categorised as horizontal, vertical and diagonal clustering,

although this classification is not rigid; clusters can fall into

more than one category in respect to their production links

and intra-cluster firms may be clustered diagonally with

other businesses, but vertically and horizontally with others.

Horizontal clustering refers to linkages between

complementary firms that produce similar goods but each

link adds value to the production chain of the tourism

experience product. They compete with one another but are

inter-linked through a network of suppliers, service and

customer relations, selling similar products and using similar

processes (Bathelt et al. 2004; Michael 2007). Vertical

clustering refers to the co-location of firms operating at

different stages in the value chain, which minimises

logistical and distributional costs and enhances

specialisation (Michael 2003). Finally, diagonal clustering

occurs where complementary firms create a bundle of

separate products and services into a single tourism product

and become 'symbiotic' e.g. firms with separate production

processes supply activities such as transport, hospitality and

accommodation (Michael 2003, 2007). Diagonal clustering

implies economies of scope internal to the firm, whereas

horizontal and vertical clustering are about external

economies of scale and the synergies between products. All

forms of clustering are dynamic and can be expected to evolve

during the lifecycle of any tourism destination.

A Spatial Perspective of Cooperation and Competition

Applied to the TALC

The working relationships between tourism businesses

in tourism destinations as spatial units of analysis with

regional economies and actors or stakeholders focus on the

relationship between co-operation and competition for

markets (Coles 2006). The destination product is perceived

by the tourism as a unified tourism product in relation to

19

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

other destinations but within a destination there is

competition between the different businesses, providing the

elements of the tourism product. This co-existence between

cooperation and competition is dual, dynamic and can be

affected by the perspectives adopted by the actors

(individuals and organizations), based on desired benefits

and the nature of the projects (Wang and Krakover 2008).

Actors' norms and values towards one another and towards

the destination community are not static and shape their

interrelationships as rivals or collaborators throughout

destination development as well as political attitudes in the

destination (Brackenbury 2006; Grngsj 2003; Wang and

Krakover 2008; Zehrer and Raich 2010).

The spatial configuration of destinations is also

dynamic as resort popularity changes over time. At the first

stages of destination development, successful resorts cast

an agglomeration shadow on others as a concentration of

new resorts emerge around successful destinations as a

result of increasing returns. Out of these emerging

asymmetries, a core-periphery configuration and spatial

competition may then occur (Papatheodorou 2006). At this

point, centripetal forces of agglomeration always coexist with

centrifugal forces of deglomeration in spatial dualism: as

flows increase the pressure on natural and environmental

resources can prove detrimental. Moreover, land rents and

subsequently hotel and other supporting services in popular

resorts tend to be very high, discouraging additional tourists.

Therefore, it may be argued that an optimum size of resort

development may exist where the net gains from external

economies are maximized. Nonetheless, such an optimal

point is only attainable in the frictionless world of neoclassical economy. When the carrying capacity point is

surpassed, however, tourism flow auto-correlation becomes

negative resulting in deglomeration unless rejuvenation is

achieved (Butler 1980; Papatheodorou 2004).

The nature and impact of changing levels of

agglomeration on cooperation and competition throughout

the lifecycle of destinations have generally been ignored,

although other spatial aspects of tourism development have

been discussed in that context. Hall (2006: 83) elaborated on

the influences of spatial interaction and mobility in the

changing patterns of tourism and tourisn destinations,

arguing that ... destinations should be primarily

conceptualised as points in space that are subject to a range

of factors which influence location. Papatheodorou (2006)

adopted a similar approach in dealing with the spatial

implications of competition in the context of the destination

lifecycle, and the development of the core-periphery pattern

around many tourism destinations. His arguements about

the way interactions develop over time as agglomeration

takes place noted the need for strategies to enable destination

20

attractions to cooperate at the regional level and thus be able

to compete at the international level, particularly with multinational corporations. His conclusion that competition

among destinations and tourism producers can be healthy

and sustainable only if it is considered with the context of

their common future (Papatheodorou 2006: 82) places the

debate about cooperation and competition in the global

context as destinations are effectively always competing at

the global scale in modern tourism. Gordon's (1994) model

suggests that variations between tourism destinations in the

speed of the lifecycle and number of tourists reflect differences

in the capacity to manage or restrain processes of competition,

which could lead to crowding and environmental

degradation.

In the context of the TALC, Coles (2006) notes the

comparisons that can be made between models used in

retailing and destination development, particularly in the

context of the creation, marketing, selling and modification

of the product over its life-span. He argues, as does Russell

(2006a) also, whether the process is a cycle or a "wheel",

with developments such as agglomeration and

deglomeration, being responsive to entrepreneurial inputs

and innovations, and particularly reflective of price

considerations at specific periods. Tourism, particularly in

its mass form, is heavily price dependent in its markets, and

competition in mass tourism destinations, many of which

have become very similar to one another in terms of offerings

(attractions, climate, accessibility) as they reach the mature

stages of the TALC, often becomes heavily, if not almost

entirely, price-focused. Innovations and events which affect

the price of a destination can cause major changes in the

cost-effectiveness of that location and its appeal to the market

(Russell 2006a).

Surprisingly, there has been little focus on the role of

entrepreneurs in the development of tourism destinations,

yet their contributions can significantly change, often

abruptly, the relationships between a destination and its

markets and the nature of competition and cooperation

within a tourism cluster (Butler and Russell 2010). As well

as the impact of entrepreneurs and innovators in changing

the path of the TALC and the relationships affecting this,

increasingly the impact of events and chance are being felt

in many destinations. Catastrophes such as conflict,

earthquakes, tsunamis and disease all change the path of

development of destinations, sometimes resulting in the

disappearance of destinations and their replacement with

new developments in other locations (Butler and Suntikul

2010; Russell 2006b), sometimes stimulating cooperation for

survival of a destination, in other cases shifting the balance

of competition to favour one location or one type of

development over another.

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

Irrespective of the direction of such change, the

occurrence of changes in the relationship between

competition and cooperation can result from the intervention

of both endogenous and exogenous forces as illustrated by

Weaver and Oppermann (2000). They argue that the evolution

of tourism destinations is subject to a number of triggers

which can be summarised as intentional or unintentional

and internal (endogenous) or external (exogenous) to the

destination itself. In this context an intentional endogenous

trigger might be destination infrastructure upgrading, while

an exogenous intentional one could be legislation changes

such as visa requirements by a higher level government. An

endogenous unintentional trigger could be local conflict or

violence, while an exogenous unintentional one might be

currency revaluation (Weaver and Opperman 2000). They

argue that a movement from intentional and endogenous

implies a loss of control by a destination over its development

cycle, a situation which could be reflected in changes in

alliances (e.g., for marketing) and viability of organisations

(e.g., for tourism promotion).

growth, prime, deceleration and several options of the after

life phase. It also describes their characteristics in terms of

how individual partnerships change over time and whether

there are commonalities in their dynamics of evolution (e.g.

decision making, leadership, commitment) in relation to

deliberately undefined scale of success. A TALC perspective

to explain tourism network development consisting of 5

stages: foundation, configuration, implementation,

stabilisation and transformation has been proposed by

Zehrer and Reich (2010). These stages are parallel to the

original stages of the model i.e., exploration involvement,

development, consolidation, stagnation, and post-stagnation

(decline, rejuvenation, or stabilisation). Zehrer's and Reich's

model refers more to the levels of cooperation in terms of size

of the network and engagement in network activities than

the nature of cooperation in Caffyn's model.

Two models for cooperation between tourism

businesses throughout a destination's lifecycle have been

suggested more recently. A tentative tourism partnership life

cycle model from an organisational evolution perspective

(Caffyn 2000) describes 6 phases: pre-partnership, take-off,

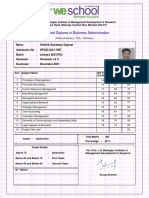

A conceptual model for predicting the likely extent and

nature of cooperation and competition between businesses

at changing levels of agglomeration at the regional scale and

spatial proximity at the local scale in each stage of the TALC

model has been suggested (Figure 1). The first curve from

Application of the TALC model to the relationships between

cooperation, competition and agglomeration at the local and

regional scale

*between neighbouring individual businesses

Figure 1. Relationships between Agglomeration,Ccooperation, and Competition for Tourists between Businesses

Throughout the TALC.

(1) Agglomeration; (2) Regional (cluster) Cooperation/Competition; (3) Local cooperation/competition between individual

neighbouring businesses

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

21

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

the left (Line one) in the figures indicates the levels of

agglomeration of tourism firms. The two other lines (Lines

two, three) illustrate the differing levels of cooperation/

competition in relation to increasing agglomeration of

businesses. The bell-shaped line (Line two) illustrates the

levels of regional cooperation or regional competition

between businesses. Line three outlines the levels of local

cooperation or local competition between intra-destination

individual businesses. In the discussion below, each stage

of Zehrer and Raich's (2010) model is related to differing

levels of agglomeration of businesses and other facilities and

impacts on their importance on cooperation and competition

throughout the stages of the TALC. At the Exploration

(foundation) stage, there is usually a small growing number

of operating businesses at low levels of agglomeration

(Haywood 2006; Papatheodorou 2004).

Tourism actors must perceive that the benefits of

optimising gains from economies of-scale will exceed the

costs in order for them to collaborate and define ground rules

regarding interaction and communication. Actors become

network-promoters themselves and might be supported by

regional institutions (Zehrer and Raich 2010). Local and

regional cooperation is likely to evolve but competition will

be almost non-existent as business activity would still be at

its preliminary stage where the numbers of tourists and

businesses are few and continued and regular visitation is

not established. At the Involvement (configuration) stage,

local and regional cooperation and competition begin to grow

and some forms of vertical clustering are likely to emerge as

the destination experience and identity is built from various

complementary products and services. Tourism businesses

may still be in the process of building initial trust with their

neighbours and establishing regional collaborative

mechanisms, where detailed design of symmetric

collaborative relationships, including controlling

mechanisms, communication are set (Zehrer and Raich

2010). Their limited resources for cooperation can be expected

to reconcile the allocation of resources between regional and

local cooperation, and are likely to prioritise regional over

local cooperation due to the need to increase tourist numbers.

As a destination grows rapidly in the Development

(implementation) stage, daily tourism activities of network

partners emerge and critical tasks are systematically

monitored (Zehrer and Raich 2010). Agglomeration and the

levels of regional and local cooperation and competition

increase (lines one, two), and trust between managers/

owners is built. These are characterised by an increase of

vertical clustering, and more trust between neighbours which

encourage businesses to cluster horizontally. Managers

perceive regional cooperation as essential for attracting more

tourists to the area and establishing a regional identity and

22

appeal that will be vital for their business growth. More

cooperation increases and some forms of horizontal

clustering are likely to emerge. As the TALC continues

through Consolidation (stabilisation) stage, the number of

firms and tourists increases, although at a slower rate, and

business operators are likely to direct their resources at

competition with other intra-cluster businesses at the

expense of marketing through membership in regional

alliances (regional cooperation) (Figure 1, lines one, three).

There will be more complexity in the system due to the

larger number of actors and a risk of competition in the

network. These issues, including the realised outcomes of,

and unfulfiled expectations from, collaboration, will be

discussed through negotiations and compromises (Zehrer

and Raich 2010). This stage will continue up to the point of

stagnation where agglomeration levels off and regional

cooperation is no longer perceived a top priority. The growth

in local and regional cooperation can be expected to decrease

but local cooperation and competition continue to grow as

the number of tourists still increases. Both vertical and

horizontal clustering are likely to continue. The final stage

of Zehrer and Raich's transformation, the Stagnation stage

reflects a changing market and an individual assessment by

each partner which determines the continuation of the

network. The emergence of inter-sectoral collaboration of

tourism with other sectors and competencies is common in

order to maintain the authenticity and competitiveness of

the tourism destination experience (Zehrer and Raich 2010).

Here, diagonal clustering and collaboration are likely to

emerge as businesses with trust-based relationships may try

to minimize costs, protect themselves from risks and survive

as one integrated production unit.

If businesses close down, relocate or lose their appeal,

so too will regional competition and cooperation decline, as

businesses will prioritise resources for their own survival

and more likely focus on competing with their similar

neighbours or maintaining existing forms of local

cooperation. Beyond this stage, there are two main options

as the traditional TALC process continues through the post

development stage. Decline may ensue and result in the

closing down of businesses, restructuring of the destination,

or the conversion of businesses to non-tourism outlets

(Agarwal 2002, 2006; Baum 2006). Moreover, forces

counteracting economies of scale deriving from

agglomeration may also exist (as noted earlier), such as

congestion costs and environmental degradation, while

greater competition in high-density areas could cause new

firms to locate, and existing firms to relocate, in alternative

less-developed areas (Butler 1980) where tourism businesses

may diversify into other activities pushing tourism into

peripheral areas (Gordon 1994) (Figure 1, Line one).

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

Beyond the point where any benefits of agglomeration

would be reached, de-glomeration would prevail. This will

reduce density as well as local cooperation between

neighbouring individual intra-destination businesses, at the

expense of redirecting resources back to regional cooperation

in an attempt to bring tourists back to the area, and to better

compete with other destinations and extra-destination

businesses (Line two). It is also possible that in the decline/

rejuvenation stages of the TALC, the intervention of

exogenous forces might result in cooperation between

individual neighbouring businesses remaining at the same

level as before or even increase as a result of possible

governmental incentives or the availability of other external

resources to stimulate regional cooperation (Line three).

Thus it is difficult to predict how the levels of cooperation at

the local or regional scales will be influenced by decline or

rejuvenation of the destination.

Summary

It is likely that in terms of local and regional

competition (Lines two, three) in the first stages of the TALC

(exploration, involvement and development stages) as a

destination develops the density of businesses increases and

local competition between co-located businesses also

intensifies. This would mean that tourists would

increasingly have more choice and businesses would have

to adjust to a more competitive business environment. When

destinations approach the 'consolidation stage', businesses

are more likely to direct their resources to competition with

other intra-destination cluster businesses (local

competition). This would be at the expense of marketing

through membership in regional alliances (regional

cooperation) for the purpose of competing with other

destinations (regional competition). Therefore, it can be

expected that regional competition would level off in the

stagnation phase and even begin to decrease. Beyond the

stagnation stage decline or rejuvenation may ensue in the

TALC, but cooperation between individual neighbouring

businesses (Line three) could remain at the same level as

earlier since some businesses may try to increase tourist

numbers by strengthening linkages and business cooperation

in marketing with their neighbours. In the case of decline,

agglomeration as well as local competition between intracluster individual businesses can be expected to decrease,

with businesses increasing resources in regional

cooperation, in order to bring tourists back to the area by

competing directly with other destinations and extra-cluster

businesses (regional competition).

Conclusions and Agenda for Future Research

The paper has suggested a conceptual model for

studying the relationships between the spatial variable of

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

proximity/density of tourism businesses in a destination

(cluster) and the degree of local versus regional competition

and cooperation between those businesses within the

destination (local) and outside the destination (region)

through the stages of the TALC. Some of the research on

which the model is based (Weidenfeld, et al. 2011) suggests

that agglomeration is positively related to local cooperation/

competition, and negatively related to regional cooperation/

competition between businesses in tourism clusters. It has

not been speculated on whether such relationships with the

stage of the TALC are in any way causal, i.e. whether the

stage of development of a destination affects the nature of

cooperation or competition between attractions within a

destination or region, although this would not seem to be

unreasonable.

The paper has also thrown light on the possible

relationship between the stages of the TALC and

agglomeration economies, which include the economic

utilities and benefits from costs reductions, efficiency gains,

a local pool of specialised and flexible labour, the provision

of shared inputs infrastructure and services (particularly

transport) and the maximisation of flows of information and

ideas that accrue from the geographical concentration of firms

(Gordon and McCann 2000). The model is based in part on

the identified relationships between cooperation,

competition, spatial proximity and spatial density

(agglomeration), the interrelationships between these aspects

and the levels of agglomeration of SMTEs (Weidenfeld et al.

2011) and on applications of the TALC to explain dynamic

cooperation between tourism firms (Caffyn 2000; Zehrer and

Raich 2010).

It is limited in that it ignores the role of local leadership

and political factors which may derive from destination

community objectives and other stakeholders' interests, as

well as external influences. Future studies should take into

account the interrelationships between social and business

relations between actors, and the possible influences of

potentially important in- and out- migration of new players

throughout the TALC, which may influence trust amongst

actors. When studying these issues, two questions need to

be considered; the first one relates to the possibility of

assessing the degree of collaboration or cooperation between

partners; the second concerns the identification of the

optimal conditions in which a significant pattern of

collaboration can exist and the actions/forces needed to

favour such conditions (Baggio 2011; Butler 2009). Further

study is necessary to determine both the nature of the

relationships suggested here and the influence of

endogenous and exogenous factors on the behaviour of

individual tourism enterprises during the TALC of a

destination.

23

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

References

AGARWAL, S. (2002). Restructuring Seaside Tourism. The Resort Life Cycle. Annals of Tourism Research 29(1): 2555.

AGARWAL, S. (2006). Coastal Resort Restructuring and the TLC. In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle Conceptual and Theoretical Issues

(Volume 2). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 201218.

BAGGIO, R. (2011). Collaboration and Cooperation in a Tourism Destination: A Network Science Approach. Current Issues in Tourism 14(2 ): 183

189.

BAGGIO, R. and COOPER, C. (2010). Knowledge Transfer in a Tourism Destination: The Effects of a Network Structure. The Service Industries Journal

30(10): 17571771.

BALE, J. (1976). The Location of the Manufacturing Industry-Conceptual Frameworks in Geography. Edinburgh. Oliver and Boyd.

BATHELT, H., MALMBERG, A. and MASKELL, P. (2004). Clusters and Knowledge: Local Buzz, Global Pipelines and the Process of Knowledge

Creation. Progress in Human Geography 28(1): 3156.

BAUM, T. G. (2006). Revisiting the TALC: Is There an Off-ramp? In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle-Conceptual and Theoretical Issues

(Volume 2). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 219230.

BAUM, J. and MEZIAS, S. (1992). Localized Competition and Organisational Failure in the Manhattan Hotel Industry. Administrative Science

Quarterly 37(4): 580604.

BRACKENBURY, M. (2006). Has Innovation Become a Routine Practice that Enables Companies to Stay Ahead of the Comprtition in the Travel

Industry? Innovation and Tourism Policy. OECD Publishing: 7183.

BRAMWELL, B. and LANE, B. (Eds) (2000). Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability. Clevedon. Channel View

Publications.

BROWN, K. G. and GEDDES, R. (2007). Resorts, Culture, and Music: The Cape Breton Tourism Cluster. Tourism Economics 13(1): 129141.

BUHALIS, D. (2006). The Impact of Information Technology on Tourism Competition. In Papatheodorou, A. (Ed) Corporate Rivalry and Market

Power, Competition Issues in Tourism: An Introduction. London I.B. Tauris: 143171.

BUTLER, R. W. (1980). The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. Canadian Geographer / Le

Gographe Canadien 24(1): 512.

BUTLER, R. W. (2006). The Origins of the Tourism Area Life Cycle. In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Applications and Modifications

(Volume 1). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 1326.

BUTLER, R. W. (2009). Tourism Destination Development: Cycles and Forces, Myths and Realities. Tourism Recreation Research 34(3): 247254.

BUTLER, R. W. and RUSSELL, R. (2010). Giants of Tourism Key Individuals in the Development of Tourism. Wallingford. CABI.

BUTLER, R. W. and SUNTIKUL, W. (2010). Political Change and Tourism. Oxford. Goodfellow.

CAFFYN, A. (2000). Is There a Tourism Partnership Life Cycle? In Bramwell, B. and Lane, B. (Eds.) Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships Clevedon,

UK. Channel View Publications: 200229.

CLAV, S. A. (2007). The Global Theme Park Industry. Wallingford, UK. CABI.

COHEN, J. P. and MORRISON, J. C. P. (2005). Agglomeration Economies and Industry Location Decisions: The Impacts of Spatial and Industrial

Spillovers. Regional Science and Urban Economics 35: 215237.

COLES, T. (2006). Enigma Variations? The TALC, Marketing Models and the Descendants of the Product Life Cycle. In Butler, R. W. (Ed) The Tourism

Area Life Cycle - Conceptual and Theoretical Issues (Volume 2). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 4966.

ERKUS-ZTRK, H. (2009). The Role of Cluster Types and Firm Size in Designing the Level of Network Relations: The Experience of the Antalya

Tourism Region. Tourism Management 30(4): 589597.

FYALL, A. and GARROD, B. (2005). Tourism Marketing: A Collaborative Approach. Clevedon. Channel View Publication.

FYALL, A., LEASK, A. and GARROD, B. (2001). Scottish Visitor Attractions: A Collaborative Future. International Journal of Tourism Research (3):

211228.

GARAY, L. and CNOVES, G. (2011). Life Cycles, Stages and Tourism History: The Catalonia (Spain) Experience. Annals of Tourism Research 38(2):

651671.

GARNHAM, B. (1996). Alliances and Liaisons in Tourism: Concepts and Implications. Tourism Economics 2(1): 6177.

GORDON, I. (1994). Crowding, Competition and Externalities in Tourism: A Model of Resort Life Cycles. Geographical Systems 1: 289307.

GORDON, I. and GOODALL, B. (2000). Localities and Tourism. Tourism Geographies 2(3): 290311.

GORDON, I. R. and MCCANN, P. (2000). Industrial Clusters: Complexes, Agglomeration and/or Social Networks? Urban Studies 37(3): 513532.

GRNGSJ, Y. V. F. (2003). Destination Networking Co-opetition in Peripheral Surroundings. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics

Management 33(5): 427448.

Hall, M. C. (2004). Small Firms and Wine and Food Tourism in New Zealand: Issues of Collaboration, Clusters and Lifestyles. In Thomas, R. (Ed.)

Small Firms in Tourism-International Perspectives. London. Elsevier: 167181.

HALL, C. M. (2006). Space-time Aaccessibility and the TALC: The Role of Geographies of Spatial Interaction and Mobility in Contributing to an

Improved Understanding of Tourism. In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle - Conceptual and Theoretical Issues (Volume 2). Clevedon.

Channelview Publications. 83100.

HALL, C. M. and PAGE, S. R. (1999). The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space. London. Routledge.

24

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

HALL, C.M. and WILLIAMS, A. M. (2008). Tourism and Innovation. London Routledge.

HAYWOOD, K. M. (2006). Legitimising the TALC as a Theory of Development. In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle - Conceptual and

Theoretical Issues (Volume 2). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 2944. .

HENRY, N. and PINCH, S. (2000). Spatialising Knowledge: Placing the Knowledge Community of Motor Sport Valley. Geoforum 31: 191208.

HJALAGER, A. (2000). Tourism Destinations and the Concept of Industrial Districts. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2(3): 199213.

HUDSON, R. (2005). Economic Geographies, Circuits, Flows and Spaces. London. Sage.

HUYBERS, T. and BENNETT, J. (2003). Inter-firm Cooperation at Nature-based Tourism Destinations. Journal of Socio-Economics 32: 571587.

IOANNIDES, D. and PETERSEN, T. (2003). Tourism 'Non-entrepreneurship' in Peripheral Destinations: A Case Study of Small and Medium

Tourism Enterprises on Bornholm, Denmark. Tourism Geographies 5(4): 408435.

JACKSON, J. and MURPHY, P. (2002). Tourism Destinations as Clusters: Analytical Experiences from the New World. Tourism and Hospitality

Research 4(1): 3652.

KRUGMAN, P. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. Journal of Political Economy 99(3): 483499.

LADE, C. (2010). Developing Tourism Clusters and Networks: Attitudes to Competition Along Australia's Murray River. Tourism Analysis 15(6):

649661.

MALMBERG, A. and MASKELL, P. (2002). The Elusive Concept of Localisation Economies: Towards a Knowledge-based Theory of Spatial

Clustering. Environment and Planning A 34: 429449.

MASSON, S. and PETIOT, R. (2009). Can the High Speed Rail Reinforce Tourism Attractiveness? The Case of the High Speed Rail between Perpignan

(France) and Barcelona (Spain). Technovation 29(9): 611617.

MICHAEL, E. J. (2003). Tourism Micro-clusters. Tourism Economics 9(2): 133145.

MICHAEL, E. J. (2007). Micro-clusters: Antiques, Retailing and Business Practice. Oxford, UK. Elsevier.

MICHAEL, E. J. and HALL, C. M. (2007). A Path for Policy. In Michael, E. J. (Ed.) Micro-Clusters and Networks: The Growth of Tourism. Oxford.

Elsevier: 127140.

MITCHELL, R. and SCHREIBER, C. (2007). Wine Tourism Networks and Clusters: Operation and Barriers in New Zealand Micro-clusters and Networks: The

Growth of Tourism. Oxford, UK. Elsevier: 79102.

MORRISON, A. M. and MILL, R. C. (1992). The Tourism Ssystem: An Introduction Text (Second edition). New Jersey, U.S. Prentice-Hall International

Editors.

NEFFKE, F., HENNING, M., BOSCHMA, R., LUNDQUIST, K.-J. and OLANDER, L.-O. (2011). The Dynamics of Agglomeration Externalities Along

the Life Cycle of Industries. Regional Studies 45(1): 4965.

NEWLANDS, D. (2003). Competition and Cooperation in Industrial Clusters: The Implications for Public Policy. European Planning Studies 11(5):

521532.

NORDIN, S. (2003). Tourism Clustering and Innovation-Paths to Economic Growth and Development. Oestersund, Sweden. European Tourism Research

Institute, Mid-Sweden University.

PAPATHEODOROU, A. (2004). Exploring the Evolution of Tourism Resorts. Annals of Tourism Research 31(1): 219337.

PAPATHEODOROU, A. (2006). Introduction. In Papatheodorou, A. (Ed.) Corporate Rivalry, Market Power and Competition Issues in Tourism. London.

Tauris: 119.

RACO, M. (1999). Competition, Collaboration and the New Industrial Districts: Examining the Institutional Turn in Local Economic Development.

Urban Studies 36(5&6): 951968.

RUSSELL, R. (2006a). The Contribution of Entrepreneurship Theory to the TALC Model. In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle - Conceptual

and Theoretical Issues (Volume 2). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 105123.

RUSSELL, R. (2006b). Chaos Theory and its Application to the TALC Model. In Butler, R. W. (Ed.) The Tourism Area Life Cycle - Conceptual and

Theoretical Issues (Volume 2). Clevedon. Channelview Publications: 164180.

SAXENA, G. (2005). Relationships, Networks and the Learning Regions: Case Evidence from the Peak District National Park. Tourism Management

26: 277289.

SHAW, G. and WILLIAMS, A. (2002). Critical Issues in Tourism: A Geographic Perspective (Second edition). Oxford, UK. Blackwell.

SHAW, G. and WILLIAMS, A. (2004). Tourism and Tourism Spaces. London. Sage

STORPER, M. (2000). Globalization, Localisation, and Trade. In Clark, G. L., Feldman, M. P. and Gertler, M. S. (Eds.) Oxford Handbook of Economic

Geography. Oxford. Oxford University Press: 146165.

SWARBROOKE, J. (2002). The Development and Management of Visitor Attractions. Oxford. Butterworth-Heinemann.

TSANG, E. W. K. and YIP, P. S. L. (2009). Competition, Agglomeration, and Performance of Beijing Hotels. The Service Industries Journal 29(2): 155

171.

WANG, Y. and FESENMAIER, D. R. (2007). Collaborative Destination Marketing: A Case Study of Elkhart County, Indiana. Tourism Management 28:

863875.

WANG, Y. and KRAKOVER, S. (2008). Destination Marketing: Competition, Cooperation, or Coopetition? International Journal of Contemporary

Hospitality Management 20(2): 126141.

WEAVER, D. and OPPERMAN, M. (2000). Tourism Management. Milton. Miley.

WEIDENFELD, A., BUTLER, R. W. and WILLIAMS, A. M. (2011). The Role of Clustering, Cooperation and Complementarities in the Visitor

Attraction Sector. Current Issues in Tourism 14(7): 595629.

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

25

The Resort Lifecycle: Butler & Weidenfeld

WILLIAMS, A. (2006). Lost in Translation? International Migration, Learning and Knowledge. Progress in Human Geography 30(5): 588607.

ZEHRER, A. and RAICH, F. (2010). Applying a Lifecycle Perspective to Explain Tourism Network Development. The Service Industries Journal 30(10):

16831705.

Submitted: November 5, 2011

Accepted: February 9, 2012

26

Tourism Recreation Research Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012

You might also like

- KPMG CII Travel Tourism Sector ReportDocument46 pagesKPMG CII Travel Tourism Sector ReportshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Coopetition - A Systematic Review, Synthesis, and Future Research DirectionsDocument25 pagesCoopetition - A Systematic Review, Synthesis, and Future Research DirectionsyrperdanaNo ratings yet

- A Conference Interpreters View - Udo JorgDocument14 pagesA Conference Interpreters View - Udo JorgElnur HuseynovNo ratings yet

- RAMPT Program PlanDocument39 pagesRAMPT Program PlanganeshdhageNo ratings yet

- Final Lego CaseDocument20 pagesFinal Lego CaseJoseOctavioGonzalez100% (1)

- Evaluating Tourist Destination Performance: Expanding The Sustainability ConceptDocument16 pagesEvaluating Tourist Destination Performance: Expanding The Sustainability ConceptBea AndreaNo ratings yet

- Devops Case StudiesDocument46 pagesDevops Case StudiesAlok Shankar100% (1)

- A Review On Value Creation in Tourism IndustryDocument10 pagesA Review On Value Creation in Tourism IndustryPablo AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Sample Company Presentation PDFDocument25 pagesSample Company Presentation PDFSachin DaharwalNo ratings yet

- A Project Report ON A Study of Promotion Strategy and Customer Perception of MC Donalds in IndiaDocument18 pagesA Project Report ON A Study of Promotion Strategy and Customer Perception of MC Donalds in IndiaShailav SahNo ratings yet

- Erp Vendor Directory v4 0Document118 pagesErp Vendor Directory v4 0Melina MelinaNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Value of Collaborations in Tourism Networks A Case Study of Elkhart County IndianaJournal of Travel and Tourism MarketingDocument15 pagesAssessing The Value of Collaborations in Tourism Networks A Case Study of Elkhart County IndianaJournal of Travel and Tourism MarketingDiana CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- A Stakeholder Perspective On Policy Indicators of Destination CompetitivenessDocument7 pagesA Stakeholder Perspective On Policy Indicators of Destination CompetitivenessGrace Kelly Avila PeñaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 2Document6 pagesPresentation 2Jeffrey AyerasNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S144767701630002X MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S144767701630002X MainUndrakhZagarkhorlooNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1447677022000031 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S1447677022000031 MainPauNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 12 09493Document22 pagesSustainability 12 09493bibuNo ratings yet

- Arti 2Document8 pagesArti 2Mayori Cruzeth Coral RamirezNo ratings yet

- Development of Tourism DestinationsDocument23 pagesDevelopment of Tourism DestinationsTomi SitumorangNo ratings yet

- A Study of Various Alliances in Travel ADocument25 pagesA Study of Various Alliances in Travel ACardenas JuanNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Service Dominant Logic and Its Implications For Tourism Management PDFDocument8 pagesAspects of Service Dominant Logic and Its Implications For Tourism Management PDFDeny P. SambodoNo ratings yet

- Krzelj-Colovic, RadicDocument6 pagesKrzelj-Colovic, RadicJhely Ann CastroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1447677021001674 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S1447677021001674 MainPauNo ratings yet

- Toward A Theoretical Framework of Collaborative Destination MarketingDocument12 pagesToward A Theoretical Framework of Collaborative Destination MarketingalzghoulNo ratings yet

- 2008 Tourism Competition-Cooperation or COOPETITIONDocument16 pages2008 Tourism Competition-Cooperation or COOPETITIONKomang MonicaNo ratings yet

- Travel Agencies - TODocument9 pagesTravel Agencies - TOAlvaro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Engagement in Destination Management: A Systematic Review of LiteratureDocument16 pagesStakeholder Engagement in Destination Management: A Systematic Review of LiteratureΑντώνης ΤσίκοςNo ratings yet

- Centralised Decentralisation of Tourism DevelopmentDocument25 pagesCentralised Decentralisation of Tourism Developmentcxt667No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0019850121001838 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0019850121001838 Maingreen VestNo ratings yet

- PPM 2017 02SI SolakisDocument14 pagesPPM 2017 02SI SolakisPiyushSahuNo ratings yet

- What Is The Impact of Hotels On Local Economic Development? Applying Value Chain Analysis To Individual Businesses Jonathan Mitchell, Xavier Font and Shina LiDocument12 pagesWhat Is The Impact of Hotels On Local Economic Development? Applying Value Chain Analysis To Individual Businesses Jonathan Mitchell, Xavier Font and Shina LiRetno ArianiNo ratings yet

- Current Scenario of CSR in The Hotel Industry of BangladeshDocument16 pagesCurrent Scenario of CSR in The Hotel Industry of BangladeshMD Rifat ZahirNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Professional Service Firms Expansion Challenges On Internationalization Processes and PerformanceDocument19 pagesThe Impact of Professional Service Firms Expansion Challenges On Internationalization Processes and Performancechung yvonneNo ratings yet

- Journal of Destination Marketing & Management: Joan Serra, Xavier Font, Milka IvanovaDocument11 pagesJournal of Destination Marketing & Management: Joan Serra, Xavier Font, Milka IvanovaTrần Thái Đình KhươngNo ratings yet

- Focus On Destination CompetitivenessDocument3 pagesFocus On Destination Competitivenessapi-360220088No ratings yet

- MPRA Paper 100670Document10 pagesMPRA Paper 100670Luz Mary MendozaNo ratings yet

- 03 - Literature ReviewDocument8 pages03 - Literature ReviewMannu GoyatNo ratings yet

- Sustainable TourismDocument12 pagesSustainable TourismSanti AzzahrahNo ratings yet

- Destination Competitiveness A Model and DeterminantsDocument12 pagesDestination Competitiveness A Model and DeterminantsNestor SolisNo ratings yet

- The Causes and Effects of Quality of Brand Relationship and Customer EngagementDocument12 pagesThe Causes and Effects of Quality of Brand Relationship and Customer EngagementMonika GuptaNo ratings yet

- Andersson 2009 Tourism-Management PDFDocument10 pagesAndersson 2009 Tourism-Management PDFDivnaNo ratings yet

- Tourism Management: Mariia Perelygina, Deniz Kucukusta, Rob LawDocument13 pagesTourism Management: Mariia Perelygina, Deniz Kucukusta, Rob LawJeramie Nicole ParacNo ratings yet

- A Configurational Approach To Entrepreneurial Orientation and CooperationDocument12 pagesA Configurational Approach To Entrepreneurial Orientation and Cooperationstynx784No ratings yet

- Exploring Clustering As A Destination Development Strategy For Rural CommunitiesDocument4 pagesExploring Clustering As A Destination Development Strategy For Rural CommunitiesTarek SouheilNo ratings yet

- Competitive Analysis of The Bulgarian Seaside Destination Sunny Beach: A Cluster ApproachDocument11 pagesCompetitive Analysis of The Bulgarian Seaside Destination Sunny Beach: A Cluster ApproachJesusAlvarezValdesNo ratings yet

- The Role of Digitalisation in Value Creation and AppropriationDocument9 pagesThe Role of Digitalisation in Value Creation and AppropriationSofia VieroNo ratings yet

- Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and IndicatorsDocument46 pagesDestination Competitiveness: Determinants and IndicatorsBhodzaNo ratings yet

- Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences: Review ArticleDocument7 pagesKasetsart Journal of Social Sciences: Review ArticleMuhamad Amiruddin HusniNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Tourism Destination Competitiveness in VietnamDocument13 pagesFactors Affecting Tourism Destination Competitiveness in VietnamNông Đức ThắngNo ratings yet

- Customers' Understanding of Engagement AdvertisingDocument20 pagesCustomers' Understanding of Engagement AdvertisingKAMNo ratings yet

- From Fragmentation To Collaboration in Tourism Promotion, An Analysis of The Adoption of IMC in The Amalfi Coast PDFDocument24 pagesFrom Fragmentation To Collaboration in Tourism Promotion, An Analysis of The Adoption of IMC in The Amalfi Coast PDFAdin RadinsyahNo ratings yet

- Destination CompetitivenessDocument46 pagesDestination CompetitivenessNinna Durinec100% (1)

- Innovative Business Models in Tourism Industry: December 2019Document13 pagesInnovative Business Models in Tourism Industry: December 2019Hassan AnwaarNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Tourman 2020 104128Document14 pages10 1016@j Tourman 2020 104128Mai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Case Study of The Successful Strategic TransformatDocument13 pagesCase Study of The Successful Strategic TransformatArpit PandeyNo ratings yet

- Abstract:: Inter-Organizational Collaboration Characteristics and Outcomes: A Case Study of The Jeddah FestivalDocument14 pagesAbstract:: Inter-Organizational Collaboration Characteristics and Outcomes: A Case Study of The Jeddah FestivalMohamad Ikhsan NurullohNo ratings yet

- Tourism Destination Benchmarking: Evaluation and Selection of The Benchmarking PartnersDocument18 pagesTourism Destination Benchmarking: Evaluation and Selection of The Benchmarking PartnersRima RhimzNo ratings yet

- Tourism Destination CompetitivDocument31 pagesTourism Destination CompetitivmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Tourism and Hotel Competitive ResearchDocument26 pagesTourism and Hotel Competitive ResearchIliana SanmartinNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 11 06351 v2Document30 pagesSustainability 11 06351 v2Ngo AlanNo ratings yet

- Bus Strat Env - 2021 - Attanasio - Stakeholder Engagement in Business Models For Sustainability The Stakeholder Value FlowDocument15 pagesBus Strat Env - 2021 - Attanasio - Stakeholder Engagement in Business Models For Sustainability The Stakeholder Value FlowMaurício MendoncaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877042814051258 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S1877042814051258 MainNabuweya NoordienNo ratings yet

- Local Tourism Governance A Comparison of Three Network ApproachesDocument23 pagesLocal Tourism Governance A Comparison of Three Network ApproachesYaiza PuertaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Strategic Management Research Lines in Hospitality and TourismDocument22 pagesEvolution of Strategic Management Research Lines in Hospitality and TourismLuis MotaNo ratings yet

- Marketing Intelligence & Planning: Emerald Article: Value Equity in Event Planning: A Case Study of MacauDocument16 pagesMarketing Intelligence & Planning: Emerald Article: Value Equity in Event Planning: A Case Study of MacauNikos FlagkakisNo ratings yet

- Responsbile Tourism Shared ValueDocument20 pagesResponsbile Tourism Shared ValueSoofisu SepidehNo ratings yet

- 21 A-CSR in Tourism Sustainable Development - 2021 - Madanaguli - Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in The Tourism Sector ADocument15 pages21 A-CSR in Tourism Sustainable Development - 2021 - Madanaguli - Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in The Tourism Sector AArchana PooniaNo ratings yet

- Theories of Change: Change Leadership Tools, Models and Applications for Investing in Sustainable DevelopmentFrom EverandTheories of Change: Change Leadership Tools, Models and Applications for Investing in Sustainable DevelopmentKaren WendtNo ratings yet

- Tourism in ChinaDocument9 pagesTourism in ChinashinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Compititiveness Destination 1Document6 pagesCompititiveness Destination 1shinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Tourism Egypt ArticleDocument8 pagesTourism Egypt ArticleshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- MasterCard Muslim IndexDocument38 pagesMasterCard Muslim IndexshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Developing The Non-Muslim Tourist DestinationDocument25 pagesDeveloping The Non-Muslim Tourist DestinationshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- (Eric Laws, Harold Richins, Jerome Agrusa, Noel SCDocument237 pages(Eric Laws, Harold Richins, Jerome Agrusa, Noel SCshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Developing The Non-Muslim Tourist DestinationDocument25 pagesDeveloping The Non-Muslim Tourist DestinationshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Islamization of Malasyian EconomyDocument58 pagesIslamization of Malasyian EconomyshinkoicagmailcomNo ratings yet

- Iso Iatf 16949 FaqsDocument3 pagesIso Iatf 16949 Faqsasdqwerty123No ratings yet

- Equity Research Report - CIMB 27 Sept 2016Document14 pagesEquity Research Report - CIMB 27 Sept 2016Endi SingarimbunNo ratings yet

- Wipro Internship ExperienceDocument3 pagesWipro Internship ExperienceSimranjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- ACC221 Quiz1Document10 pagesACC221 Quiz1milkyode9No ratings yet

- Ethical DileemaasDocument46 pagesEthical DileemaasRahul GirdharNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ingles Cuestionario Quimestre 2-1Document3 pagesIngles Cuestionario Quimestre 2-1Ana AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Bills of Material: Rev. Date Description by CHK'D Reviewed ClientDocument5 pagesBills of Material: Rev. Date Description by CHK'D Reviewed ClientChaitanya Sai TNo ratings yet

- Bank CodesDocument2,094 pagesBank CodeskoinsuriNo ratings yet

- Grievance 1Document10 pagesGrievance 1usham deepika100% (1)

- A Minor Project Report: Product Analysis of ItcDocument83 pagesA Minor Project Report: Product Analysis of ItcDeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Advanced Diploma in Business Administration: Hrithik Sandeep GajmalDocument1 pageAdvanced Diploma in Business Administration: Hrithik Sandeep GajmalNandanNo ratings yet

- BSI Cascading Balanced Scorecard and Strategy MapDocument2 pagesBSI Cascading Balanced Scorecard and Strategy MapWellington MartilloNo ratings yet