Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CRIME

Uploaded by

roellyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CRIME

Uploaded by

roellyCopyright:

Available Formats

Procurement fraud

Investigative techniques

to help mitigate risk

A whistleblower at a large manufacturer alleged that an

employee in the procurement department was colluding with

a vendor to bill the company for security services that were

allegedly never rendered. The investigation revealed several

large round dollar invoices billed for security at events that

the company had no record of ever occurring. The vendor

admitted in an interview that some of the invoices were in

fact fictitious while other invoices were for legitimate services

rendered to the company. This scheme lasted several years and

cost the company hundreds of thousands of dollars before the

whistleblower, who worked for the employee in procurement,

tipped off internal audit.

An analysis of purchases by the maintenance department

of another large company revealed that the price paid

for various supplies was two and sometimes three times

higher than market value. An investigation revealed a

connection between the vendor and maintenance department

procurement officer.

These two real life examples have a common thread. Both

companies had controls in place such as segregation of duties

and supervisor approval that were either overridden by either

collusion or abuse of approval authorities. Learning from the

investigative process that uncovered the techniques used to

perpetrate the frauds, and employing similar investigative

techniques to assess procurement activity on a periodic,

proactive basis may be helpful in identifying anomalies like

relationships between employees and vendors and anomalies

in the pattern of purchasing.

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners describes

occupational fraud as the use of ones occupation for personal

enrichment through the deliberate misuse or misapplication

of the employing organizations resources or assets. Fraud

is a potential risk in most businesses. Organizations instill a

certain amount of trust in their employees in order to operate,

and those within the procurement function are entrusted with

access to vendor selection, vendor files, accounts payable,

invoice approval, and purchase orders, which can provide

an opportunity to commit fraudulent activity such as bid

rigging, false billing schemes, vendor kickbacks, and conflicts

of interest. Whether the employee is a purchasing agent,

controller, accounts payable manager, or any other employee

essential to the operations of a business, a dishonest employee

can present a potential fraud risk for the organization.

The degree of risk a business may face can be assessed by

examining Donald Cresseys Fraud Triangle and determining

if any of its factors might be an issue for employees

with purchasing responsibilities. Cressey proposed that

employees are more likely to commit fraud if three factors

exist: 1) incentives and pressures, 2) opportunity and

3) rationalization. Given the increased financial tension

in todays economy, more and more employees could

be feeling increased financial pressure and reductions in

resources due to layoffs may compromise segregation of

duties potentially creating more opportunity for dishonest

behavior. In addition, because of the current economic

environment, some employees may feel they can justify, or

rationalize, their behavior. This situation can be perceived

as an ideal opportunity by dishonest employees, including

those who might be involved in procurement duties within

an organization. If dishonest employees feel an increased

pressure to perform or produce results, and if an organization

is simultaneously lacking appropriate controls and segregation

of duties, such employees might view this situation as an

opportunity to use their procurement role to commit fraud.

Some of the methods a procurement employee may use to

commit potential fraud include:

Kickbacks. Kickbacks are the giving or receiving anything

of value to influence a business decision. Kickbacks may be

undisclosed payments made by vendors to employees in

return for favorable treatment, such as bid rigging or inside

bidding information. The vendor may also approach an

employee about submitting or approving invoices for goods

or services that were never received, and in exchange the

vendor provides the employee with a kickback. Kickbacks

can be payments of cash, but can also be in a form that is

more difficult to detect, such as payment of personal loans

or credit card bills, transfers of property or vehicles at less

than fair market value, lavish vacations, or a hidden interest

in the vendors business.

Conflicts of interest. If an employee has an interest in the

financial well-being of a vendor, a conflict of interest could

exist. This may take the form of being a part-owner in the

vendor company, or knowing someone close, e.g., a spouse

or other family member, who works for the vendor and can

receive rewards for business the employee provides. Any of

these situations can impair a dishonest employees ability to

conduct business with the organizations best

interests in mind.

It is important to be aware of anomalies in the purchasing

function such as:

Expenditures do not make economic sense (dollar amount

and timing).

Orders are consistently made from one vendor without

inquiring with other vendors for comparison purposes.

Costs of goods or services are higher than

competing vendors.

Poor documentation for expenditures.

One-time payments to vendors (vendor often not officially

set up and cleared through accounts payable).

Large round-dollar payments.

Data analysis can help with identifying anomalies in

purchasing. For example, analyzing the vendor database,

payroll database, and accounts payable database can assist

organizations identify potential undisclosed relationships

between employees and vendors and identify anomalies in

purchasing for potential follow-up such as:

Common bank account, address, and phone numbers

between vendors and employees that may indicate a

potential conflict of interest.

Duplicate invoices with the same supplier.

Invoices from different suppliers with the same dollar

amount, date and invoice number.

suspicious about certain transactions. Interviews at all levels

within the company can give insight into the daily operations

and can reveal fraud risks which may be otherwise unknown

to the organization.

Background checks can provide information on the

background, integrity, and reputation of selected individuals

and entities. A small amount of time spent performing a

background investigation, such as Secretary of State records

searches, might reveal connections between employees

and vendors. Additionally, it can provide history on vendors

performance, legal proceedings, and other

relevant information.

Electronic discovery, such as extracting and analyzing email

files, can identify any questionable correspondence between

vendors and employees using an organizations computers.

These tools can be used proactively by organizations to help

identify potential fraudulent activity. Recognizing the red flags

commonly associated with procurement fraud and using

tools such as data analysis, in addition to other investigative

techniques such as interviews and background checks, can

go a long way in helping the organization mitigate the risk of

fraud in the procurement function.

For more information, please contact:

Data analysis can provide trend data, such as the number of

invoices from suppliers over time, unusual invoice number

sequencing, and dollars spent for goods and services

purchased from a particular vendor. This can assist with

answering the question, does the dollar amount and

timing of purchases from a particular vendor make sense?

Furthermore, analyzing the actual purchase orders and invoices

can assist with answering the question, does the price paid

for the goods and services make sense?

Ron Schwartz

Partner

Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP

+1 404 220 1540

rschwartz@deloitte.com

In addition to data analysis described above, some commonly

used investigative techniques can also be used to help identify

anomalies in purchasing:

Employee interviews can be useful in discovering potential

procurement fraud. Interviewers sometimes find that

employees have information about potential inappropriate

relationships between employees and vendors or are

This paper contains general information only and is based on the experiences and research of Deloitte practitioners. Deloitte is not, by means of this

presentation, rendering accounting, auditing, business, financial, investment, legal or other professional advice or services. This presentation is not

a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before

making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor.

Deloitte, its affiliates, and related entities shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this paper.

About Deloitte

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, a Swiss Verein, and its network of member firms, each of which is a legally separate and

independent entity. Please see www.deloitte.com/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu and its member

firms. Please see www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of Deloitte LLP and its subsidiaries.

Copyright 2010 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved.

Member of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

You might also like

- 899 2665 1 SMDocument22 pages899 2665 1 SMLusiana DewiNo ratings yet

- Law Court SessionDocument5 pagesLaw Court SessionroellyNo ratings yet

- Regime - Free Fight LiberalismDocument2 pagesRegime - Free Fight LiberalismroellyNo ratings yet

- Tata Cara Perhitungan Harga Satuan Pekerjaan Pengecatan Dan Finishing (Analisa Bow)Document12 pagesTata Cara Perhitungan Harga Satuan Pekerjaan Pengecatan Dan Finishing (Analisa Bow)Sora100% (2)

- Doel HandwritingDocument1 pageDoel HandwritingroellyNo ratings yet

- International Reputation NamesDocument26 pagesInternational Reputation NamesroellyNo ratings yet

- Building A Computer 3 PDFDocument7 pagesBuilding A Computer 3 PDFroellyNo ratings yet

- Checklist Performance ImprovementDocument6 pagesChecklist Performance ImprovementroellyNo ratings yet

- Water - Water - WaterDocument24 pagesWater - Water - WaterroellyNo ratings yet

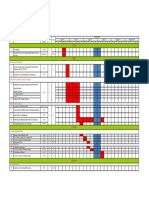

- Proyect Sheduling Iso 9001 2015Document1 pageProyect Sheduling Iso 9001 2015roellyNo ratings yet

- Refugess - Who Care ?Document8 pagesRefugess - Who Care ?roellyNo ratings yet

- IRCA Application RequirementsDocument1 pageIRCA Application RequirementsarunkumarNo ratings yet

- ISO Sni Award 2018Document3 pagesISO Sni Award 2018roellyNo ratings yet

- BabyDocument27 pagesBabyroellyNo ratings yet

- Regime of NeoliberalismDocument2 pagesRegime of NeoliberalismroellyNo ratings yet

- FB Cheater Doc3Document2 pagesFB Cheater Doc3roellyNo ratings yet

- IRCA Application RequirementsDocument1 pageIRCA Application RequirementsarunkumarNo ratings yet

- Knowlede MGTDocument10 pagesKnowlede MGTroellyNo ratings yet

- ISORisk Management PlanDocument14 pagesISORisk Management PlanroellyNo ratings yet

- ISO Checklist of Mandatory Documentation Required by IATF 16949 en YES OKDocument20 pagesISO Checklist of Mandatory Documentation Required by IATF 16949 en YES OKroelly100% (2)

- Iso Consultancy Published1Document3 pagesIso Consultancy Published1roellyNo ratings yet

- TNV F 001Document2 pagesTNV F 001roellyNo ratings yet

- Cover Proposal MaretDocument2 pagesCover Proposal MaretroellyNo ratings yet

- My Reg CardDocument1 pageMy Reg CardroellyNo ratings yet

- ISO - Automated Audit Management PDFDocument6 pagesISO - Automated Audit Management PDFroellyNo ratings yet

- UKAS - Logo Regulations 4 14KDocument2 pagesUKAS - Logo Regulations 4 14KroellyNo ratings yet

- Fina & Acc Follow Up MKT: NN ManhoaDocument7 pagesFina & Acc Follow Up MKT: NN ManhoaroellyNo ratings yet

- Rekap Absen Quick ProDocument2 pagesRekap Absen Quick ProroellyNo ratings yet

- Employee list with positions and statusDocument5 pagesEmployee list with positions and statusroellyNo ratings yet

- 4 - FLOWCheck Sheet 2Document1 page4 - FLOWCheck Sheet 2roellyNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Economics For Competition Lawyers - ADP Part OnlyDocument44 pagesEconomics For Competition Lawyers - ADP Part Onlyeliza timciucNo ratings yet

- Return To The Source Selected Speeches of Amilcar CabralDocument112 pagesReturn To The Source Selected Speeches of Amilcar Cabraldjazzy456No ratings yet

- (123doc) - New-Tuyen-Chon-Bai-Tap-Chuyen-De-Ngu-Phap-On-Thi-Thpt-Quoc-Gia-Mon-Tieng-Anh-Co-Dap-An-Va-Giai-Thich-Chi-Tiet-Tung-Cau-133-TrangDocument133 pages(123doc) - New-Tuyen-Chon-Bai-Tap-Chuyen-De-Ngu-Phap-On-Thi-Thpt-Quoc-Gia-Mon-Tieng-Anh-Co-Dap-An-Va-Giai-Thich-Chi-Tiet-Tung-Cau-133-TrangLâm Nguyễn hảiNo ratings yet

- Texas Commerce Tower Cited for Ground Level FeaturesDocument1 pageTexas Commerce Tower Cited for Ground Level FeatureskasugagNo ratings yet

- Research For ShopeeDocument3 pagesResearch For ShopeeDrakeNo ratings yet

- The Life of St. John of KronstadtDocument47 pagesThe Life of St. John of Kronstadtfxa88No ratings yet

- 19 Preposition of PersonalityDocument47 pages19 Preposition of Personalityshoaibmirza1No ratings yet

- The Impact of E-Commerce in BangladeshDocument12 pagesThe Impact of E-Commerce in BangladeshMd Ruhul AminNo ratings yet

- Vak Sept. 16Document28 pagesVak Sept. 16Muralidharan100% (1)

- The Marcos DynastyDocument19 pagesThe Marcos DynastyRyan AntipordaNo ratings yet

- Bajaj - Project Report - Nitesh Kumar Intern-Bajaj Finserv Mumbai - Niilm-Cms Greater NoidaDocument61 pagesBajaj - Project Report - Nitesh Kumar Intern-Bajaj Finserv Mumbai - Niilm-Cms Greater NoidaNitesh Kumar75% (20)

- En The Beautiful Names of Allah PDFDocument89 pagesEn The Beautiful Names of Allah PDFMuhammad RizwanNo ratings yet

- Chap 1 ScriptDocument9 pagesChap 1 ScriptDeliza PosadasNo ratings yet

- LP DLL Entrep W1Q1 2022 AujeroDocument5 pagesLP DLL Entrep W1Q1 2022 AujeroDENNIS AUJERO100% (1)

- Airtel A OligopolyDocument43 pagesAirtel A OligopolyMRINAL KAUL100% (1)

- Marketing MetricsDocument29 pagesMarketing Metricscameron.king1202No ratings yet

- Types of Majority 1. Simple MajorityDocument1 pageTypes of Majority 1. Simple MajorityAbhishekNo ratings yet

- Power Plant Cooling IBDocument11 pagesPower Plant Cooling IBSujeet GhorpadeNo ratings yet

- Construction Equipments Operations and MaintenanceDocument1 pageConstruction Equipments Operations and MaintenanceQueenie PerezNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoiceDp PandeyNo ratings yet

- Immediate Flood Report Final Hurricane Harvey 2017Document32 pagesImmediate Flood Report Final Hurricane Harvey 2017KHOU100% (1)

- 17.06 Planned Task ObservationsDocument1 page17.06 Planned Task Observationsgrant100% (1)

- Municipal Best Practices - Preventing Fraud, Bribery and Corruption FINALDocument14 pagesMunicipal Best Practices - Preventing Fraud, Bribery and Corruption FINALHamza MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Bureau of Energy EfficiencyDocument2 pagesBureau of Energy EfficiencyrkNo ratings yet

- MR - Roleplay RulebookDocument12 pagesMR - Roleplay RulebookMr RoleplayNo ratings yet

- In - Gov.uidai ADHARDocument1 pageIn - Gov.uidai ADHARvamsiNo ratings yet

- Wagner Group Rebellion - CaseStudyDocument41 pagesWagner Group Rebellion - CaseStudyTp RayNo ratings yet

- Safety Management System Evaluation ToolsDocument26 pagesSafety Management System Evaluation ToolsMahmood MushtaqNo ratings yet

- English 7 WorkbookDocument87 pagesEnglish 7 WorkbookEiman Mounir100% (1)

- WP (C) 267/2012 Etc.: Signature Not VerifiedDocument7 pagesWP (C) 267/2012 Etc.: Signature Not VerifiedAnamika VatsaNo ratings yet