Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2001 - Rev Saude Publ

Uploaded by

lbnucciCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2001 - Rev Saude Publ

Uploaded by

lbnucciCopyright:

Available Formats

502

Rev Sade Pblica 2001;35(6):502-7

www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

Nutritional status of pregnant women:

prevalence and associated pregnancy outcomes

Estado nutricional de gestantes: prevalncia e

desfechos associados gravidez

Luciana Bertoldi Nuccia, Maria Ins Schmidta, Bruce Bartholow Duncana, Sandra Costa

Fuchsa, Eni Teresinha Fleckb and Maria Margarida Santos Brittoc

a

Departamento de Medicina Social da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal do Rio

Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. bCentro de Cincias da Sade da Universidade de Fortaleza.

Fortaleza, CE, Brasil. CFaculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal da Bahia. Salvador, BA, Brasil

Keywords

Obesity.# Pregnancy complications.#

Body mass index.# Nutritional status.#

Prevalence. Prenatal care. Risk

factors. Brazil.

Abstract

Descritores

Obesidade.# Complicaes na

gravidez.# ndice de massa corporal.#

Estado nutricional.# Prevalncia.

Cuidado pr-natal. Fatores de risco.

Brasil.

Resumo

Correspondence to:

Luciana Bertoldi Nucci

Rua da Granja Julieta, 9/34

04721-060 So Paulo, SP, Brasil

E-mail: lbnucci@terra.com.br

Partial supported by Ministrio da Sade; Programa de Apoio a Ncleos de Excelncia (PRONEX, Process n

661041/1998-4); Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientfico e Tecnolgico (CNPq, Process n 520368/95-9);

Fundao de Apoio Pesquisa do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS); ; Organizao Pan-Americana da Sade (OPAS);

Fundo de Incentivo Pesquisa (FIPE, Process n 97217 do Hospital de Clnicas de Porto Alegre, and Bristol-Myers Squibb

Foundation.

Submitted on 5/4/2001. Reviewed on 29/8/2001. Approved on 27/9/2001.

Introduction

Although obesity is well recognized as a current public health problem, its prevalence

and impact among pregnant women have been less investigated in Brazil. The objective

of the study was to evaluate the impact of pre-obesity and obesity among pregnant

women, describing its prevalence and risk factors, and their association with adverse

pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

A cohort of 5,564 pregnant women, aged 20 years or more, enrolled at aproximately

20 to 28 weeks of pregnancy, seen in prenatal public clinics of six state capitals in

Brazil were followed up, between 1991 and 1995. Prepregnancy weight, age,

educational level and parity were obtained from a standard questionnaire. Height was

measured in duplicate and the interviewer assigned the skin color. Nutritional status

was defined using body mass index (BMI), according to World Health Organization

(WHO) criteria. Odds ratios and 95% confidence interval were calculated using

logistic regression.

Results

Age-adjusted prevalences (and 95% CI) based on prepregnancy weight were:

underweight 5.7% (5.1%-6.3%), overweight 19.2% (18.1%-20.3%), and obesity 5.5%

(4.9%-6.2%). Obesity was more frequently observed in older black women, with a

lower educational level and multiparous. Obese women had higher frequencies of

gestational diabetes, macrosomia, hypertensive disorders, and lower risk of microsomia.

Conclusions

Overweight nutritional status (obesity and pre-obesity) was seen in 25% of adult

pregnant women and it was associated with increased risk for several adverse

pregnancy outcomes, such as gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia.

Introduo

A obesidade um problema atual de sade pblica, com repercusses na gravidez.

Pouco se sabe sobre sua prevalncia em gestantes brasileiras. Assim, realizou-se

estudo com o objetivo de avaliar o impacto da obesidade e da pr-obesidade na

gravidez, descrevendo sua prevalncia, fatores de risco e sua associao com

complicaes da gestao.

Nutritional status of pregnant women

Nucci LB et al.

Rev Sade Pblica 2001;35(6):502-7

www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

Mtodos

Uma coorte de 5.564 gestantes, com idade maior ou igual a 20 anos, com 20 a 28

semanas de gestao, atendidas em servios de pr-natal geral do Sistema nico de

Sade em seis capitais brasileiras, foram seguidas entre 1991 e 1995. Medidas de

peso pr-gravdico, idade, escolaridade e paridade foram obtidas mediante entrevistas

utilizando-se questionrio padronizado. A altura foi medida em duplicata, e a cor da

pele, descrita pelo entrevistador. O estado nutricional foi estabelecido a partir do

ndice de massa corporal (IMC), utilizando-se os critrios da Organizao Mundial

da Sade. Razo de chances e intervalo de confiana de 95% foram calculados por

meio de regresso logstica.

Resultados

As prevalncias (IC95%) ajustadas para idade foram: magreza (IMC<18,5 kg/m2),

5,7% (5,1%-6,3%); pr-obesidade (25<IMC<30 kg/m2), 19,2% (18,1%-20,3%); e

obesidade (30<IMC kg/m2), 5,5% (4,9%-6,2%). A obesidade foi mais freqente em

mulheres mais velhas, negras, com menor grau de escolaridade e multparas.

Mulheres obesas apresentaram risco maior para diabetes gestacional, macrossomia,

distrbios hipertensivos, e menor risco para microssomia.

Concluses

Sobrepeso (pr-obesidade ou obesidade) ocorreu em 25% das gestantes adultas

estudadas e associou-se a vrios riscos de complicaes de gravidez, como diabetes

gestacional e pr-eclampsia.

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization

(WHO), the increased frequency of obesity in many

countries can be characterized as a pandemia of major public health concern.13 Maternal nutritional status is an important determinant of pregnancy outcomes since prepregnancy underweight has been traditionally considered a risk factor for adverse gestation outcomes.3 Obesity also increases pregnancy

complications, such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, and perinatal morbimortality.12

Brazil is a heterogeneous country regarding its

population characteristics, and health problems of preobesity and obesity coexist with undernutrition. Recent trend analyses of nutritional status have placed

the problem of obesity squarely on the Brazilian public health agenda.8

The objective of the present study was to assess

prepregnancy nutritional status among women seen

in prenatal clinics of the Brazilian national health system, its population correlates and its associated adverse pregnancy outcomes.

METHODS

The study was conducted in prenatal care clinics of

the national health system (Sistema nico de Sade

SUS) of six state capitals in Brazil, between 1991 and

1995. A cohort of 5,564 consecutive women aged 20

years and more, otherwise non-diabetic, were followed

from about weeks 20-28 of gestationtill delivery. Ana-

lysis was carried out for 5,314 women, as in 250 there

was a lack of information required to calculate prepregnancy body mass index (BMI).

At enrollment, a standardized questionnaire provided information on age, prepregnancy weight (in

kilograms), years of education, and parity. Maternal

height was measured in duplicate and recorded in

centimeters according to the standard protocol. Skin

color was subjectively assigned. Prepregnancy nutritional status was classified based on BMI, according

to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria: underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), normoweight (18.5 kg/

m2 BMI <25 kg/m2), pre-obesity (25 kg/m2 BMI<

30 kg/m2), and obesity (BMI30 kg/m2). Women who

fall in the latter two categories were also characterized as overweight.13

Gestational diabetes mellitus was defined according

to the current WHO criteria as fasting plasma glucose of

at least 7.0 mmol/l or a 2-hour-post 75g glycemia of at

least 7.8 mmol/l.14 Gestational age was characterized

according to hierarchical criteria based on four clinical

examinations: ultrasound before week 26 in 52% of the

sample; ultrasound after week 26 consistent with neonatal age estimation or last menstrual period in 15%;

reported last menstrual period consistent with neonatal

age estimation or uterine height in 23%; and neonatal

age estimation, ultrasound after week 26, uterine height,

or last menstrual period in the remaining 10%. Macrosomia was defined as birth weight at or above the 90th

percentile for the gestational age of the study sample;

microsomia was defined as birth weight below the 10th

percentile for the gestational age. Hypertensive disor-

503

504

Nutritional status of pregnant women

Nucci LB et al.

Rev Sade Pblica 2001;35(6):502-7

www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

ders were ascertained through chart review and classified according to the National High Blood Pressure

Education Program Working Group. Pre-eclampsia (hypertension after week 20 of gestation associated with

proteinuria or seizures) included only cases of new onset hypertension.

5,314 women included in the analysis and of those

excluded due to missing information. Inability to calculate prepregnancy BMI was more frequently seen

among multiparous women with lower educational

level and miscellaneous skin color in the Salvador

center.

Frequencies of underweight, pre-obesity and obesity and their 95% confidence intervals , both crude

and adjusted, are displayed, the latter obtained

through logistic regression.11,15 Odds ratios for pregnancy outcomes were also calculated using logistic

regression. Statistical analyses were performed using

the statistical software SAS.

Age specific prevalences of prepregnancy nutritional

status are presented in Table 2. Prevalences of underweight decreased in the age groups from 9% for women

aged 20 to 24 years to 3.4% for those 30 years and more.

In contrast, for pre-obesity and obesity, prevalences

increased with age. Overall age-adjusted prevalences

(95% CI) based on prepregnancy weight were: underweight 5.7% (5.1%-6.3%), pre-obesity 19.2% (18.1%

20.3%), and obesity 5.5% (4.9%-6.2%) (p<0.001).

The Ethical Committees of the Institutions approved the study protocol, and participants signed

the study consent.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the distribution of characteristics of

Table 3 describes age-adjusted prevalences (95%

CI) of prepregnancy nutritional status, according to

study center, educational level, skin color, and parity.

Although the Salvador center had the highest prevalence of underweight, the obesity prevalence in this

Table1 - Characteristics of studied and excluded pregnant women aged 20 to 48, 1990 to 1994.

Characteristics

Studied sample*

Women with missing BMI*

(n=5,314)

(n=250)

N

%

N

%

P value

Age

20 to 24

1,783

33.6

83

33.2

25 to 29

1,691

31.8

78

31.2

30

1,840

34.6

89

35.6

Education

<8 years

2,303

43.4

180

72.0

8-11 years

2,480

46.8

67

26.8

12 years

518

9.8

3

1.2

Skin color

White

2,391

45.2

51

20.7

Mixed

2,188

41.4

45

61.1

Black

710

13.4

151

18.2

Parity

0

1,449

30.6

39

16.5

1

1,589

33.6

59

24.9

2

904

19.1

50

21.1

3

788

16.7

89

37.6

Study center

Porto Alegre

1,072

20.2

38

15.2

So Paulo

1,232

23.2

4

1.6

Rio de Janeiro

549

10.3

8

3.2

Salvador

881

16.6

104

41.6

Fortaleza

1,122

21.1

51

20.4

Manaus

458

8.6

45

18.0

*The small variation in category totals results from missing information relating to the characteristic in question.

0.9

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

Table 2 - Frequency (95%CI) of prepregnancy World Health Organization nutritional status* categories among 5,314 women

aged 20 to 48, 1990 to 1994.

Age (years)

Underweight

(n=309)

Nutritional status*

Pre-obesity

(n=1,086)

Obesity

(n=336)

20 to 24 (n=1,783)

25 to 29 (n=1,691)

30 (n=1,840)

P

Overall

Overall age adjusted**

9.0 (7.8-10.5)

5.0 (4.1-6.2)

3.4 (2.7-4.4)

<0.001

5.8 (5.2-6.5)

5.7 (5.1-6.3)

14.6 (13.0-16.3)

20.6 (18.7-22.6)

26.0 (24.0-28.0)

<0.001

20.4 (19.4-21.5)

19.2 (18.1-20.3)

3.8 (3.0-4.7)

6.2 (5.2-7.5)

8.9 (7.7-10.3)

0.001

6.3 (5.7-7.0)

5.5 (4.9-6.2)

*BMI cut points according to WHO13: underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), pre-obesity (25.0 kg/m2BMI<30 kg/m2) and obesity

(BMI30.0 kg/m2)

**Adjusted to represent frequencies for 27 year old women

Nutritional status of pregnant women

Nucci LB et al.

Rev Sade Pblica 2001;35(6):502-7

www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

center was also high. Overweight was more frequent

in study centers in the more industrialized south and

southeast regions (Porto Alegre, So Paulo, and Rio

de Janeiro) (p<0.001). Porto Alegre and Rio de Janeiro showed the highest adjusted frequencies for

obesity. Educational level was inversely related to

nutritional status, obesity being more prevalent among less educated women (p=0.03). Overweight was

commonly seen among black women, and obesity

was more prevalent in black than in white or miscellaneous skin color women (p=0.01). Nulliparous women presented a different nutritional status distribution than multiparous ones, the age-adjusted prevalence of underweight was higher and pre-obesity and

obesity was lower than among parous women. Those

having three or more previous pregnancies had higher

age-adjusted prevalence of obesity (p=0.002).

Table 4 demonstrates an inverse association of nutritional status and microsomia. Pre-obese and obese

women had lower risk of microsomia (OR=0.65, 95%

CI 0.48-0.88, and OR=0.47, 95% CI 0.260-0.84, respectively). On the other hand, they showed a higher

risk of having gestational diabetes mellitus (OR=2.0,

95% CI 1.60-2.5 and OR=2.4, CI 95% 1.7-3.4), macrosomia (OR=1.6, 95% CI 1.3-2.0 and OR=1.5, CI 95%

1.1-2.2), and hypertensive disorders (OR=2.5, 95% CI

2.0-3.0 and OR=6.6, 95% CI 5.0-8.6), than women with

normal nutritional status. Obesity was also a risk factor

for pre-eclampsia (OR=3.9, 95% CI 2.4-6.4).

DISCUSSION

Brazilian national health system provides care for

approximately 75% of the population4. These data

show that more than1/3 of women seen in selected

prenatal clinics of the national health system feel out

of normal nutritional range (18.5<BMI<25.0). Of

these, there were about 4 women overweight for every

underweight one. Though these prevalences varied

somewhat over the categories such as age, educational

level, skin color, parity, and geographic region, sig-

Table 3 - Age adjusted* prevalence (95%CI) of prepregnancy World Health Organization nutritional status** among 5,314

women aged 20 to 48, by study center, years of education, skin color and parity, 1990 to 1994.

Characteristics

Underweight

% (95%CI)

Nutritional status**

Pre-obesity

% (95%CI)

Center of study

Porto Alegre

(n=1,059)

3.7 (2.7-5.1)

23.5 (21.0-26.3)

So Paulo

(n=1,221)

4.7 (3.6-6.1)

22.5 (20.2-25.1)

Rio de Janeiro

(n=536)

5.8 (4.0-8.4)

25.2 (21.6-29.1)

Salvador

(n=877)

9.2 (7.4-11.3)

16.5 (14.1-19.2)

Fortaleza

(n=1,108)

6.9 (5.5-8.5)

16.7 (14.5-19.1)

Manaus

(n=447)

4.6 (3.1-6.9)

18.7 (15.2-22.8)

P

<0.001

<0.001

Years of education

<8

(n=2,271)

6.1 (5.1-7.1)

21.3 (19.6-23.2)

8-11

(n=1,134)

5.9 (5.0-6.9)

20.1 (18.5-21.8)

11

(n=1,829)

4.2 (2.7-6.6)

18.8 (15.6-22.4)

P

0.33

0.33

Skin color

White

(n=2,355)

5.3 (4.4-6.3)

20.7 (19.0-22.4)

Mixed

(n=2,164)

6.6 (5.6-7.7)

19.4 (17.8-21.2)

Black

(n=705)

5.5 (4.0-7.5)

22.4 (19.4-25.7)

P

0.16

0.23

Parity

0

(n=1,433)

6.8 (5.6-8.2)

16.6 (14.7-18.8)

1

(n=1,572)

5.1 (4.1-6.3)

22.1 (20.1-24.3)

2

(n=887)

5.0 (3.7-6.8)

24.5 (21.7-27.6)

3

(n=779)

6.3 (4.6-8.7)

21.1 (18.2-24.3)

P

0.15

<0.001

*Adjusted to represent frequencies for 27 year old women

**BMI cut points according to WHO13: underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), pre-obesity (25.0 kg/m2BMI<30

(BMI30.0 kg/m2)

Obesity

% (95%CI)

8.6 (7.0-10.6)

5.3 (4.1-6.7)

8.5 (6.4-11.2)

7.4 (5.8-9.5)

4.1 (3.1-5.5)

4.5 (2.8-7.2)

<0.001

7.1 (6.0-8.3)

6.0 (5.0-7.0)

4.2 (2.8-6.2)

0.03

5.5 (4.6-6.5)

6.6 (5.6-7.8)

8.4 (6.5-10.8)

0.01

5.2 (4.0-6.6)

6.9 (5.7-8.4)

5.8 (4.4-7.6)

9.4 (7.4-11.9)

0.002

kg/m2) and obesity

Table 4 - Odds ratio (95%CI) for pregnancy outcomes according to nutritional status* among 5,314 women aged 20 to 48,

1990 to 1994.

Pregnancy outcomes

Underweight

OR (95%CI)

Nutritional status

Pre-obesity

OR (95%CI)

GDM

0.40 (0.19-0.85)

1.98 (1.56-2.53)

Microsomia

2.03 (1.42-2.90)

0.65 (0.48-0.88)

Macrosomia

0.56 (0.33-0.95)

1.61 (1.30-2.00)

Hypertensive disorders

0.72 (0.42-1.23)

2.46 (1.99-3.04)

Pre-eclampsia

0.70 (0.25-1.93)

1.26 (0.79-2.00)

*BMI cut points according to WHO13: underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), pre-obesity (25.0 kg/m2BMI<30

(BMI30.0 kg/m2); reference group is those with normal BMI (18.5 kg/m2BMI<25 kg/m2).

GDM - Gestational diabetes mellitus

Obesity

OR (95%CI)

2.36 (1.65-3.39)

0.47 (0.26-0.84)

1.53 (1.08-2.17)

6.60 (5.06-8.60)

3.92 (2.40-6.38)

kg/m2) and obesity

505

506

Nutritional status of pregnant women

Nucci LB et al.

nificant overweight prevalences were present in all

categories studied. These data are of a major importance given the increased risk of adverse outcomes

among overweight here demonstrated.

The study findings are consistent with recent population-based surveys of nutritional status in Brazil.

Monteiro et al7 reported an obesity prevalence of

13.3% in a probability sample of Brazilian women aged

25-64 years8 conducted in 1989. While not all women

in these population surveys have equal probability of

becoming pregnant, it is important to add to these data

from clinical samples in order to obtain a more complete picture of the significance of these recent changes

in nutritional status to current obstetric practice.

The study data illustrate important risks at both

extremes of the nutritional status spectrum, as both

under and overweight at the beginning of gestation

are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, consistent with other authors findings in different contexts. While underweight women presented a higher

frequency of microsomia,6 overweight was related to

macrosomia and other disease conditions, such as

gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders.6,12 As being overweight is commonly seen and

confers risk not only to the mother but also to the

neonate, the study findings, along with the literature,

call for greater attention to the prevention and management of obesity in childbearing age women, both

prior to and during pregnancy.

Rev Sade Pblica 2001;35(6):502-7

www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

There are some limitations in the interpretation of

these results. As the study was conducted in selected

clinics of the national health system of six capitals, representativeness cannot be assured. However, comparisons of data on educational level, nutritional status

and gestational age at delivery5 suggest that the study

sample characteristics are comparable with those of

pregnant women living in large metropolitan areas of

Brazil. In this regard, the data are also less likely to be

representative of those women seen outside of the national health system. An additional limitation is that

prepregnancy weight was reported and not objectively

measured, and thus subject to recall bias. However,

based on previous findings concerning weight recall

for Brazilian women studied outside of pregnancy10 and

other studies about referred weight,2 it seems that

weight measure bias is probably small.

As a conclusion, overweight nutritional status is

highly prevalent among women seen in prenatal public clinics of major Brazilian cities, even for the age

range of 2024 years. Approximately 25% of women

are overweight at conception. Older black multiparous

women with lower educational level and living in the

southern or southeastern regions are more likely to be

overweight at the onset of pregnancy. Maternal overweight status is associated with adverse pregnancy

outcomes. Greater awareness of these facts are key

for minimizing the risks of obesity for pregnant women

and their offspring.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The dilemma of weight control strategies for overweight pregnant women should be stressed. Although

a lesser weight gain during pregnancy might be desirable for overweight women, insufficient weight gain

is associated with an increased risk of microsomia,6

per se a risk for several undesirable outcomes, both

immediate and chronic.1 Thus, international limits for

adequate weight gain have been set for specific nutritional categories, from lean to obese. It was previously reported here that only of the overweight

women studied gained weight within these recommended limits.9

To the following people for the study regional coordination in the centers: AJ Reichelt of Santa Casa de

Misericrdia and Hospital de Clnicas de Porto Alegre;

JMD Pousada of Instituto de Perinatologia da Bahia

(IPERBA); T Yamashita of Hospital do Servidor Pblico

Estadual Francisco Morato de Oliveira, So Paulo);

ERS Spichler of Instituto Fernandes Figueira. Fundao

Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro; MM Teixeira of Servio de

Obstetrcia do Posto de Assistncia Mdica da Cadajs,

Manaus; A Costa e Forti of Maternidade Escola Assis

Chateaubriand da Universidade do Cear, Fortaleza.

REFERENCES

1. Barker D. Mothers, babies and health in later life. 2nd

ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

2. Chor D, Coutinho E, Laurenti R. Reliability of selfreported weight and height among state bank

employees. Rev Sade Pblica 1999;33:16-23.

3. Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Kramer MS.

Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse

pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 1998;338:147-52.

4. Faquim L. Planos de sade: os dois lados da regulamentao. RH em sntese [serial online] 1999;27:615. Disponvel em: http://www.gestaoerh.com.br/

artigos/legi_010.shtml [2000 ago 12]

5. Fundao IBGE. DATASUS [online] 1996. Disponvel em:

http://www.datasus.gov.br/tabnet/tabnet.htm [2000 ago 5]

6. Institute of Medicine (US). Nutrition during pregnancy.

Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 1990.

Rev Sade Pblica 2001;35(6):502-7

www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

Nutritional status of pregnant women

Nucci LB et al.

7. Monteiro CA, Mondini L, Medeiros de Souza AL,

Popkin BM. The nutritional transition in Brazil. Eur J

Clin Nutr 1995;49:105-13.

12. Wolfe H. High prepregnancy body-mass index: a

maternal-fetal risk factor. N Engl J Med

1998;338:191-2.

8. Monteiro CA, DA Benicio MH, Conde WL, Popkin

BM. Shifting obesity trends in Brazil. Eur J Clin Nutr

2000;54:342-6.

13. World Health Organization. WHO Consultation on

Obesity. Obesity: preventing and managing the global

epidemic. Geneva; 1998.

9. Nucci L, Duncan BB, Mengue S, Branchtein L,

Schmidt MI, Fleck E. Assessment of weight gain

during pregnancy in general prenatal care services of

Brazil. Cad Sade Pblica, 2001;17(6). In press.

14. World Health Organization. WHO Study Group on

Diabetes Mellitus. Prevention of Diabetes Mellitus:

report of a WHO Study Group. Geneva;1994. [WHO

Technical Report Series, 844].

10. Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Tavares M, Polanczyk CA,

Pellanda L, Zimmer PM. Validity of self-reported

weight: a study of urban Brazilian adults. Rev Sade

Pblica 1993;27:271-6.

15. Zhao PY. Logistic regression adjustment of proportion

and its macro procedure.In: Proceedings of the

Twenty-Second Annual SAS Users Group

International Conference; San Diego, California1997.

Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.,1997 p. 1045-50.

11. Wilcosky TC, Chambless LE. A comparison of direct

adjustment and regression adjustment of epidemiologic

measures. J Chronic Dis 1985;38:849-56.

507

You might also like

- Completely Reverse Heart Disease With This Revolutionary TreatmentDocument8 pagesCompletely Reverse Heart Disease With This Revolutionary TreatmentSamee's Music100% (3)

- Obesity in Pregnancy - UPTO DATEComplications and Maternal Management - UpToDateDocument43 pagesObesity in Pregnancy - UPTO DATEComplications and Maternal Management - UpToDateCristinaCaprosNo ratings yet

- JanubDocument65 pagesJanubRoel PalmairaNo ratings yet

- Byol Meridian NewDocument2 pagesByol Meridian NewRahulKumar0% (1)

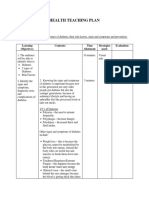

- Health Teaching Plan (Diabetes)Document6 pagesHealth Teaching Plan (Diabetes)Zam Pamate100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography AssignmentDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Assignmentapi-242256465100% (2)

- Weaknes S/ Fatigue Polyphag IaDocument5 pagesWeaknes S/ Fatigue Polyphag IaEwert Hesketh Nillama PaquinganNo ratings yet

- OBESITY AND PREGNANCY OUTCOMESDocument5 pagesOBESITY AND PREGNANCY OUTCOMESAchmad Deza FaristaNo ratings yet

- Maternal Obesity, Gestational Hypertension, and Preterm DeliveryDocument8 pagesMaternal Obesity, Gestational Hypertension, and Preterm DeliveryGheavita Chandra DewiNo ratings yet

- Safety and Efficacy ofDocument11 pagesSafety and Efficacy ofJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Maternal Pregnancy Weight Gain and The Risk of Placental AbruptionDocument9 pagesMaternal Pregnancy Weight Gain and The Risk of Placental AbruptionMuhammad Aulia KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Informe 10Document8 pagesInforme 10karen paredes rojasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ViolenceDocument6 pagesJurnal ViolenceIris BerlianNo ratings yet

- Percentage of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Attributable To Overweight and ObesityDocument7 pagesPercentage of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Attributable To Overweight and Obesitynunki aprillitaNo ratings yet

- Síndrome Metabólico (SM) en Niños y Adolescentes: Asociación Con Sensibilidad Insulínica (SI) y Con Magnitud y Distribución de La ObesidadDocument8 pagesSíndrome Metabólico (SM) en Niños y Adolescentes: Asociación Con Sensibilidad Insulínica (SI) y Con Magnitud y Distribución de La Obesidadgráficos furiososNo ratings yet

- Abed,+1114 Impacts+of+Dietary+Supplements+and+Nutrient Rich+Food+for+Pregnant+Women+on+Birth+Weight+in+Sugh+El Chmis Alkhoms+–+LiDocument8 pagesAbed,+1114 Impacts+of+Dietary+Supplements+and+Nutrient Rich+Food+for+Pregnant+Women+on+Birth+Weight+in+Sugh+El Chmis Alkhoms+–+LiLydia LuciusNo ratings yet

- Macrosmia and DMDocument4 pagesMacrosmia and DMAde Gustina SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Breast-Feeding and Risk For Childhood Obesity: Does Maternal Diabetes or Obesity Status Matter?Document7 pagesBreast-Feeding and Risk For Childhood Obesity: Does Maternal Diabetes or Obesity Status Matter?Dea Mustika HapsariNo ratings yet

- The Implications of Obesity On Pregnancy Outcome 2015 Obstetrics Gynaecology Reproductive MedicineDocument4 pagesThe Implications of Obesity On Pregnancy Outcome 2015 Obstetrics Gynaecology Reproductive MedicineNora100% (1)

- Risk factors for macrosomia in Latina womenDocument7 pagesRisk factors for macrosomia in Latina womenKhuriyatun NadhifahNo ratings yet

- Tugas Ebm Anisa Fitri HandaniDocument23 pagesTugas Ebm Anisa Fitri HandanianisFitrihandani anisaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Body Mass Index On The Incidence of Preterm LabourDocument6 pagesInfluence of Body Mass Index On The Incidence of Preterm LabourRizky MuharramNo ratings yet

- Diabetic MaternlaDocument4 pagesDiabetic MaternlaAde Gustina SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Its A Must To ReadDocument10 pagesIts A Must To ReadBNo ratings yet

- Bmi PregnancyDocument11 pagesBmi PregnancyLilik AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Effect of inadequate weight gain in overweight and obese pregnant womenDocument3 pagesEffect of inadequate weight gain in overweight and obese pregnant womenainindyaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PDFDocument5 pagesJurnal PDFWaica PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Obesidad en El EmbarazoDocument17 pagesObesidad en El Embarazodianaarias1703No ratings yet

- 08 AimukhametovaDocument10 pages08 AimukhametovahendraNo ratings yet

- Pre-Existing Diabetes Mellitus and Adverse PDFDocument5 pagesPre-Existing Diabetes Mellitus and Adverse PDFMetebNo ratings yet

- Maternal Factors For Low Birth Weight BabiesDocument3 pagesMaternal Factors For Low Birth Weight BabiesjanetNo ratings yet

- The Role of Parity in The Mode of DeliveryDocument11 pagesThe Role of Parity in The Mode of DeliveryKanuyasa GekzNo ratings yet

- Recém Ingressos Na UniversidadeDocument10 pagesRecém Ingressos Na UniversidadeanaflaviapfNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Glucose Intolerance Among Pregnant Women With Unexplained IUFDDocument5 pagesPattern of Glucose Intolerance Among Pregnant Women With Unexplained IUFDTri UtomoNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 713785Document16 pagesNi Hms 713785mnn164No ratings yet

- Ansiedade, Qualidade Do Sono e Compulsão Alimentar em Adultos Com Sobrepeso Ou Obesidade PortuguesDocument8 pagesAnsiedade, Qualidade Do Sono e Compulsão Alimentar em Adultos Com Sobrepeso Ou Obesidade Portuguesviviane coelhoNo ratings yet

- Homa TannerDocument10 pagesHoma TannerClaudia VillablancaNo ratings yet

- Obesity in Children & Adolescents: Review ArticleDocument11 pagesObesity in Children & Adolescents: Review ArticleMatt QNo ratings yet

- Preconception Care ofDocument11 pagesPreconception Care ofsipen poltekkesbdgNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of Pre-School Children From Low Income FamiliesDocument11 pagesNutritional Status of Pre-School Children From Low Income FamiliesFiraz R AkbarNo ratings yet

- Managing Obesity in Malaysian Schools Are We Doing The Right StrategiesDocument9 pagesManaging Obesity in Malaysian Schools Are We Doing The Right StrategiesArushi GuptaNo ratings yet

- SX Metabólico en NiñosDocument8 pagesSX Metabólico en NiñosCésar Ayala GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy nutrition guidelines for preconception through postpartumDocument16 pagesPregnancy nutrition guidelines for preconception through postpartumnanik setyawatiNo ratings yet

- Maternal Nutritional AssessmentDocument7 pagesMaternal Nutritional AssessmentchinchuNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Obesity in PregnancyDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Obesity in Pregnancyafmzbdjmjocdtm100% (1)

- Lactation and Maternal Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based StudyDocument6 pagesLactation and Maternal Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based StudyMoni SantamariaNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Fetal Macrosomia: ObjectiveDocument10 pagesFactors Associated With Fetal Macrosomia: ObjectiveAdib FraNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Science in MedicineDocument7 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitus: Science in MedicineNatalia_p_mNo ratings yet

- A Word of Caution Against Excessive Protein IntakeDocument8 pagesA Word of Caution Against Excessive Protein IntakeBianca MickaelaNo ratings yet

- Abstract (Summary) : The Association Between Maternal Glucose Concentration and Child BMI at Age 3 YearsDocument7 pagesAbstract (Summary) : The Association Between Maternal Glucose Concentration and Child BMI at Age 3 YearsCedric Joshua BautistaNo ratings yet

- GDM Case StudyDocument5 pagesGDM Case Studydheeptha sundarNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition Among Pregnant Women Iran StudyDocument8 pagesMalnutrition Among Pregnant Women Iran StudyKimberlyjoycsolomonNo ratings yet

- 发表 修正Document2 pages发表 修正郑心洁No ratings yet

- Nutrition in The First 1000 Days: The Origin of Childhood ObesityDocument9 pagesNutrition in The First 1000 Days: The Origin of Childhood ObesityYoki VirgoNo ratings yet

- Muest RaDocument13 pagesMuest RaBruno LinoNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factor (CVDRF) Associated Waist Circumference Patterns in Obese-Prone ChildrenDocument10 pagesCardiovascular Disease Risk Factor (CVDRF) Associated Waist Circumference Patterns in Obese-Prone ChildrenArmin Arceo DuranNo ratings yet

- Stir Rat 2014Document1 pageStir Rat 2014Dayana Cuyuche JuarezNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Kenaikan Berat Badan Rata - Rata Per Minggu Pada Kehamilan Trimester Ii Dan Iii Terhadap Risiko Berat Bayi Lahir RendahDocument7 pagesPengaruh Kenaikan Berat Badan Rata - Rata Per Minggu Pada Kehamilan Trimester Ii Dan Iii Terhadap Risiko Berat Bayi Lahir Rendahmulia rahmaNo ratings yet

- Resumo: Artigos Originais / Original ArticlesDocument7 pagesResumo: Artigos Originais / Original ArticlesRafael SedlmaierNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Kenaikan Berat Badan Rata - Rata Per Minggu Pada Kehamilan Trimester Ii Dan Iii Terhadap Risiko Berat Bayi Lahir RendahDocument7 pagesPengaruh Kenaikan Berat Badan Rata - Rata Per Minggu Pada Kehamilan Trimester Ii Dan Iii Terhadap Risiko Berat Bayi Lahir RendahmanalNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Weight GainDocument9 pagesPregnancy Weight GainKevin MulyaNo ratings yet

- JAPI Body FatDocument6 pagesJAPI Body FatBhupendra MahantaNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Syndrome in Childhood: Association With Birth Weight, Maternal Obesity, and Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument9 pagesMetabolic Syndrome in Childhood: Association With Birth Weight, Maternal Obesity, and Gestational Diabetes MellitusAnnisa FujiantiNo ratings yet

- Neck Circumference JOILANE 2020Document20 pagesNeck Circumference JOILANE 2020Joilane Alves Pereira FreireNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsNo ratings yet

- Medical Form Vehicle Licensing CharnwoodDocument12 pagesMedical Form Vehicle Licensing CharnwoodKalkin43No ratings yet

- Emailing Diabetic Wound Care White PaperDocument20 pagesEmailing Diabetic Wound Care White PaperGreatAkbar1No ratings yet

- Idf GDM Model of Care Implementation Protocol Guidelines For Healthcare ProfessionalsDocument20 pagesIdf GDM Model of Care Implementation Protocol Guidelines For Healthcare Professionalsdiabetes asiaNo ratings yet

- Himawan - BPJSDocument26 pagesHimawan - BPJSAndi Upik FathurNo ratings yet

- MCI Screening Test (FMGE) Question Paper - 2002Document678 pagesMCI Screening Test (FMGE) Question Paper - 2002Anbu Anbazhagan100% (1)

- Analysis Physiological IndicatorsDocument8 pagesAnalysis Physiological IndicatorsTatadarz Auxtero Lagria100% (1)

- The Role of Nurses in Diabetes Care and EducationDocument16 pagesThe Role of Nurses in Diabetes Care and EducationMakanjuola Osuolale JohnNo ratings yet

- Neuropati DMDocument30 pagesNeuropati DMAnisa PutriNo ratings yet

- CASP Qualitative Appraisal Checklist 14oct10Document12 pagesCASP Qualitative Appraisal Checklist 14oct10Agil SulistyonoNo ratings yet

- ANS RPN Integrated Post Test I A PDFDocument25 pagesANS RPN Integrated Post Test I A PDFdaljit chahalNo ratings yet

- 12 30 11 AADE Insulin WhitePaper PrintDocument17 pages12 30 11 AADE Insulin WhitePaper PrintMiguel Angel Fonseca RiveraNo ratings yet

- Endocrine System DiseasesDocument87 pagesEndocrine System DiseasesFahmiArifMuhammadNo ratings yet

- ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Diabetic Ketoacidosis and The Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar StateDocument23 pagesISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Diabetic Ketoacidosis and The Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar StateJulietPérezNo ratings yet

- Insulin AdministrationDocument8 pagesInsulin AdministrationskybluealiNo ratings yet

- Non-Modifiable Risk Factors AreDocument10 pagesNon-Modifiable Risk Factors ArenurNo ratings yet

- Role of Family Support in African Americans with Type 2 DiabetesDocument6 pagesRole of Family Support in African Americans with Type 2 Diabetessamiran212No ratings yet

- Diabetes in The UK 2010Document21 pagesDiabetes in The UK 2010jrjsdNo ratings yet

- List of Items For A 24 HR PharmacyDocument3 pagesList of Items For A 24 HR PharmacyasgbalajiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of The Endocrine System IIDocument129 pagesAnatomy of The Endocrine System IIShauie CayabyabNo ratings yet

- Classification Pathophysiology Diagnosis of DMDocument9 pagesClassification Pathophysiology Diagnosis of DMjohn haider gamolNo ratings yet

- Ketoacidosis A Rare Complication of Fibrocalculous Pancreatic Diabetes Ketoacidosis A Rare Complication of Fibrocalculous Pancreatic DiabetesDocument4 pagesKetoacidosis A Rare Complication of Fibrocalculous Pancreatic Diabetes Ketoacidosis A Rare Complication of Fibrocalculous Pancreatic DiabetesChintia Meliana Kathy SiraitNo ratings yet

- Urine AnalysisDocument33 pagesUrine AnalysisajaysomNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction Among Public Health Workers in Central Province Sri LankaDocument23 pagesJob Satisfaction Among Public Health Workers in Central Province Sri LankaGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Approved IFCC Recommendation On Reporting Results For Blood GlucoseDocument4 pagesApproved IFCC Recommendation On Reporting Results For Blood GlucosePham PhongNo ratings yet