Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Engineering With A Human Face

Uploaded by

Keith Smith0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views2 pageshumanitarian engineering

Original Title

Engineering With a Human Face

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documenthumanitarian engineering

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views2 pagesEngineering With A Human Face

Uploaded by

Keith Smithhumanitarian engineering

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

in my own words

Engineering with a Human Face

Bernard Amadei, Ph.D.

Professor of Civil Engineering, University of Colorado

Founding President, Engineers Without Borders USA

Dr. Bernard Amadei is a co-recipient of the 2007 Heinz Award for the

Environment, the recipient of the 2008 ENR Award of Excellence, an

elected member of the U.S. National Academy of Engineering, and an

Ashoka-Knight Fellow. In addition to creating Engineers Without Borders

USA, Dr. Amadei is the co-founder of Engineers Without Borders International. In 2013 and 2014, he served as a science envoy for the U.S. Department of State. His overarching goal: to help shape a new generation of

engineers with the education, training, and passion to change the world.

From the backyard to Belize

and beyond

My interest in engineering for developing

communities actually started in my own

backyard in 1997. I was having some

landscape work done, and the three young

men who were doing the work were

originally from Belize. As we talked in my

backyard, they told me about the needs of

young Mayan Indians in Belize, especially

with regard to curriculum development.

They wanted to start a vocational school.

They asked me, Since you are into teaching, would you be interested in helping? I said yes, but I didnt

hear from them for about two years.

Then, in 1999, I got an email inviting me to visit them in

Belize. I was on sabbatical leave at the time. I went to Belize,

where I fell in love with the land and the people. In the Mayan

village of San Pablo, I met a little girl who carried water from

the river up to the village every day. Because she had to do

this, she couldnt go to school. The people of the village asked

me if, as a civil engineer, there was anything I could do. Right

away, I thought of installing a pump that could be used to

pump water from the river to the village.

An enlightening experience

From a technical standpoint, the project was easy to design

and implement. The challenge was to come up with a solution

that was affordable for the local people, most of whom earned

less than $1.00 a day. In the jungle, there is no electricity, and

the community couldnt afford fuel for a pump. It was the first

time in my life when an engineering problem was defined

more by societal needs than by technological needs.

6 imagine

Back in Colorado, I talked to some engineering students

about working on the project, and lo and behold, some 15

students volunteered to raise funds for it. A year later, we

built a ram pump that relied on energy from a waterfall. It

was an eye-opening experience for me and for the students, who wanted to do more of that kind of practical work,

rather than learning solely from textbooks. And so Engineers Without Borders USA (EWB-USA) was born in 2001.

Today, we have around 14,000 members in the U.S.

alone. Half of those members are professional engineers.

The other half are engineering students who will eventually

graduate and become professional engineers. We have

over 300 chapters throughout the United States, and were

working in 47 countries around the world.

Working together to benefit the community

Typically, someonea Peace Corps volunteer or someone

from an NGO (non-governmental organization) or government agencywill contact us with a potential project. They

submit an application they download from our website,

which is then reviewed by professional engineers to determine whether it fits within the value system of EWB-USA:

Can we do it? Is it going to benefit the community? If the

project is accepted, its put on the website and various

chapters can bid on it. They have to show that they have

the expertise as well as professional mentors, and that they

can pull the project together and do fundraising. Based on

The challenge of improving the

daily lives of people in developing

communities calls for a new

generation of global engineers

who can operate in environments

vastly different from those in the

developed world.

From Engineering for Sustainable Human Development:

A Guide to Successful Small Scale Community Projects by

Bernard Amadei

Nov/Dec 2014

Dr. Bernard Amadei greets children in a village in Mali.

these criteria, we decide who gets the project. Then, an EWB

team will visit the site to see what the community is like and

determine the problems and needs of its people. Once a

project is selected, a chapter makes a five-year commitment

to the community.

Each chapter is responsible for raising funds for their

respective projects. The typical per-project budget is around

$30,000 to $50,000 per year. Most of that money goes to

travel, but some goes into training, equipment, and resources.

Engineering for the people

In the developed world, engineers know how to build roads

and bridges that dont collapse. We know how to build projects big and small. What we dont know much about is how

to do projects in developing countries that not only are done

well from an engineering point of view, but are also right for

the community. How do we design good solutions for a community where people make $1.00 a day? How do we design

solutions that are also accessible and reliable, and provide

long-term benefits?

One of the greatest challenges in community development

is the long-term performance of such things as pumps, buildings, and shelters. Often, charitable organizations go to these

communities, build something, and leave. The fact is that

about 60 percent of water pumps in the world installed by

NGOs fail after six months. Were not dealing simply with concrete and steel. We have to remember that were designing

solutions for human beings. This is engineering with a human

face. The solutions need to be technically sound but also

appropriate to the communities who will benefit from them.

Solutions can actually do harm if they are not well designed.

Cross-cultural challenges

We know how to build things. Its the non-engineering part

thats the challenge. How do we train people to be leaders,

and to deal with cultures that dont speak the same language,

www.cty.jhu.edu/imagine

or that have different value systems? How do we teach student engineers to deal with issues of anthropology, sociology,

language, conflict?

EWB-USA is pushing for its members to take classes in

non-technical disciplines, including sociology, anthropology,

conflict analysis and conflict management, and cultural sensitivity. Were working on an accreditation process that we want

all of our members to complete. Our goal is to make sure that

theyre ready to go into the field, that they have the education and leadership skills to assess a community in order to

address complex socio-technical problems.

Meeting complex needs

The number one problem in developing countries is water,

whether its drinking water, water for irrigation, wastewater,

or the recycling of water. Closely aligned with that is energy.

Water can be at the bottom of the well, but if you have no

energy, the water stays at the bottom of the well. You need

energy to pump, clean, store, and distribute the water. Food

and agriculture are very important, too, as are safe and

affordable shelter and transportation. Of course, health is very

important, and we work on anything, such as clinics, that can

provide for public health in communities.

Engineering diplomacy

Increasingly, we are talking about creating global citizen

engineers, individuals who can play a leadership role and

manage complex situations. Over time, EWB-USA has crept

into the engineering curriculum. Its become a mature

organization that has a place in engineering education and

practice and in international development.

In 2012, I was appointed by Secretary of State Clinton as

one of three U.S. science envoys. Over the past two years, Ive

served in various countries, including Pakistan and Nepal, to

promote science and technology from a diplomatic perspective. Were dealing with the question of how engineers

can help create a more civil society, one that brings people

together and improves the well-being of the world.

Its very rewarding to be of service to humanity. When I see

the villagers with water, smiling, I know its a success story.

Every time I see students coming back with a big smile on

their face, completely changed, thats success. Ive watched

students who had never experienced work in developing

communities come back completely transformed. Were

creating a new generation of engineers, and I know that the

engineering profession is in good hands. n

imagine

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CCC - Inverlat Case - Grupo Inverlat CaseDocument4 pagesCCC - Inverlat Case - Grupo Inverlat Casejkgonzalez100% (3)

- 132.3 Flash DistillationDocument26 pages132.3 Flash DistillationKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- BUMA 20023 - Strategic ManagementDocument104 pagesBUMA 20023 - Strategic ManagementAllyson VillalobosNo ratings yet

- 09 Registered Teacher Criteria SelfDocument15 pages09 Registered Teacher Criteria Selfapi-300095367No ratings yet

- Programming Solar CellsDocument8 pagesProgramming Solar CellsKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Highlights Realising The Right To Total Sanitation, Nakuru, KenyaDocument4 pagesEvaluation Highlights Realising The Right To Total Sanitation, Nakuru, KenyaKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- University ScholarDocument18 pagesUniversity ScholarKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- Tips For Success Resume WritingDocument32 pagesTips For Success Resume WritingKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- Cambridge ChemE SyllabusDocument7 pagesCambridge ChemE SyllabusKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- Leadership in Health CareDocument10 pagesLeadership in Health CarebullyrayNo ratings yet

- Vulnerary Activity - Final PaperDocument6 pagesVulnerary Activity - Final PaperKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- ChE 106 Course OutlineDocument2 pagesChE 106 Course OutlineKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- ChE 197 Introduction To Health Safety and Environment Syllabus 1st Sem 2014 2015 PDFDocument2 pagesChE 197 Introduction To Health Safety and Environment Syllabus 1st Sem 2014 2015 PDFKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Determination of Total Hardness in Drinking Water by Complexometric Edta TitrationDocument2 pagesQuantitative Determination of Total Hardness in Drinking Water by Complexometric Edta TitrationKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- Complexometric TitrationDocument4 pagesComplexometric TitrationZaim Akmal ZainalNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts Session-4Document45 pagesBasic Concepts Session-4Keith SmithNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 - Limits and One-Sided LimitsDocument290 pagesLecture 2 - Limits and One-Sided LimitsKeith SmithNo ratings yet

- 04 Handout 1Document5 pages04 Handout 1alhene floresNo ratings yet

- Controlling DocumentDocument113 pagesControlling Documentashok_sapfiNo ratings yet

- JD - Support To HCBPDocument1 pageJD - Support To HCBPAhire MinalNo ratings yet

- Impact of Leadership Styles On Employee Performance Evidence From Adonko Company Limited.Document84 pagesImpact of Leadership Styles On Employee Performance Evidence From Adonko Company Limited.Edward AttahNo ratings yet

- Leadership PresentationDocument29 pagesLeadership Presentationanchal tanwarNo ratings yet

- NSTP 1 ModuleDocument4 pagesNSTP 1 ModuleAllain Randy BulilanNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Partnering WellDocument17 pagesAdvantages of Partnering WellSachin PanpatilNo ratings yet

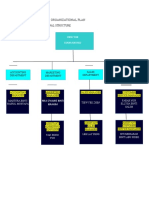

- 4.0 Management and Organizational Plan 4.1Document3 pages4.0 Management and Organizational Plan 4.1nisawzzNo ratings yet

- Topic 8 - Managing Early Growth of The New VentureDocument11 pagesTopic 8 - Managing Early Growth of The New VentureMohamad Amirul Azry Chow100% (3)

- Carter Mcnamara, Mba, PHD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC, Experts in Strategic Planning Field Guide To Nonprofit Strategic Planning and FacilitationDocument14 pagesCarter Mcnamara, Mba, PHD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC, Experts in Strategic Planning Field Guide To Nonprofit Strategic Planning and FacilitationMassoud RZNo ratings yet

- Poem We Children of The StruggleDocument3 pagesPoem We Children of The StruggleB. Jorge Botala BolosoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Leadership in OrganizationsDocument12 pagesJournal of Leadership in OrganizationsEdwyn Ramoz SinagaNo ratings yet

- Resume For Freshers Computer EngineersDocument9 pagesResume For Freshers Computer Engineersf5d5wm52100% (2)

- Specialist - Category Management.Document3 pagesSpecialist - Category Management.Rehman HazratNo ratings yet

- Mary Parker FollettDocument10 pagesMary Parker Follettapi-525419077No ratings yet

- The Icon We Admire The Most : - Group 1Document18 pagesThe Icon We Admire The Most : - Group 1mihir1811No ratings yet

- Fish Bone Diagram QmsDocument16 pagesFish Bone Diagram QmsAli ZafarNo ratings yet

- Pili Market Development CooperativeDocument6 pagesPili Market Development CooperativeLaiNe de la PazNo ratings yet

- Module 10 Q1 Challengesto HRMDocument8 pagesModule 10 Q1 Challengesto HRMprabodhNo ratings yet

- Assignment Questions - PPCDocument5 pagesAssignment Questions - PPCS R CHAITANYANo ratings yet

- HR Assignment - KeshavDocument6 pagesHR Assignment - Keshavkeshav vaigankarNo ratings yet

- Employer BrandingDocument22 pagesEmployer BrandingAyan GangulyNo ratings yet

- Measurement and Characteristics of Opinion LeaderDocument17 pagesMeasurement and Characteristics of Opinion LeaderAnurag Shankar SinghNo ratings yet

- Influence Processes and Leadership: (Lecture Outline and Line Art Presentation)Document36 pagesInfluence Processes and Leadership: (Lecture Outline and Line Art Presentation)nayemNo ratings yet

- MCQS Question Bank No. 3 For FY BBA Subject - Principles of Management PDFDocument15 pagesMCQS Question Bank No. 3 For FY BBA Subject - Principles of Management PDFronak0% (2)

- 04 School CultureDocument24 pages04 School CultureMENCAE MARAE SAPID67% (3)

- BBPP1103 Past Year Examination AnalysisDocument31 pagesBBPP1103 Past Year Examination AnalysisdamryNo ratings yet