Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anckar - On The Applicability of The Most Similar Systems Design and The Most Different Systems Design in Comparative Research

Uploaded by

AOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anckar - On The Applicability of The Most Similar Systems Design and The Most Different Systems Design in Comparative Research

Uploaded by

ACopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Social Research Methodology

ISSN: 1364-5579 (Print) 1464-5300 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsrm20

On the Applicability of the Most Similar Systems

Design and the Most Different Systems Design in

Comparative Research

Carsten Anckar

To cite this article: Carsten Anckar (2008) On the Applicability of the Most Similar Systems

Design and the Most Different Systems Design in Comparative Research, International Journal

of Social Research Methodology, 11:5, 389-401, DOI: 10.1080/13645570701401552

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645570701401552

Published online: 05 Nov 2008.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1626

View related articles

Citing articles: 12 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tsrm20

Download by: [University of Oslo]

Date: 29 September 2015, At: 05:55

Int. J. Social Research Methodology

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

Vol. 11, No. 5, December 2008, 389401

On the Applicability of the Most

Similar Systems Design and the Most

Different Systems Design in

Comparative Research

Carsten Anckar

Received 13 September 2006; Accepted 12 April 2007

Taylor and Francis Ltd

TSRM_A_240041.sgm

In comparative political research we distinguish between the Most Similar Systems Design

(MSSD) and the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD). In the present work, I argue

that the applicability of the two research strategies is determined by the features of the

research task. Three essential distinctions are important when assessing the applicability of

the MSSD and the MDSD: (1) whether or not variable interactions are studied at a

systemic level or at a sub-systemic level; (2) whether we use a deductive or inductive

research strategy and (3) whether or not we operate with a constant or varying dependent

variable. The article argues that the combination of these dimensions is essential for how

the MSSD and the MDSD can and should be used in comparative research.

International

10.1080/13645570701401552

1364-5579

Original

Taylor

02007

00

Professor

carsten.anckar@abo.fi

000002007

&Article

Francis

CarstenAnckar

(print)/1464-5300

Journal of Social(online)

Research Methodology

The Most Similar Systems Design and the Most Different Systems Design

When applying the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD), we choose as objects of

research systems that are as similar as possible, except with regard to the phenomenon,

the effects of which we are interested in assessing. The reason for choosing systems that

are similar is the ambition to keep constant as many extraneous variables as possible

(e.g. Bartolini, 1993, p. 134; Sartori, 1991, p. 250; Skocpol, 1984, p. 379). Although theoretically robust, the MSSD suffers from one serious practical shortcoming. There are a

Carsten Anckar is professor of political science (comparative politics) at bo Akademi University, Finland. His

most recent book is Determinants of the death penalty: A comparative study of the world (London & New York:

Routledge, 2004). Correspondence to: Carsten Anckar, bo Akademi University, Department of Political

Science, 20500 bo, Finland. Email: carsten.anckar@abo.fi

ISSN 13645579 (print)/ISSN 14645300 (online) 2008 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/13645570701401552

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

390

C. Anckar

limited number of countries and therefore it will never be possible to keep constant all

potential explanatory factors (e.g. Meckstroth, 1975, p. 134; Peters, 1998, pp. 3839).

At the same time, there are two different ways to conceive of the MSSD. A strict application of a MSSD, would require us to choose countries that are similar in a number of

specified variables (the control variables) and different with regard to only one aspect

(the independent variable under study). A looser application of a MSSD would be when

we choose to study countries that appear to be similar in as many background characteristics as possible, but where the researcher never systematically matches the cases on

all the relevant control variables. If the MSSD is conceived of in the latter form, most

regional comparative studies could be said to implicitly apply a MSSD.

We cannot, however, escape the criticism that any MSSD model is likely to suffer

from the problem of many variables, small number of cases (Lijphart, 1971, p. 685).

To remedy this shortcoming, Przeworski and Teune (1970) came up with an alternative strategy, which they labelled the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD). Here, the

strategy is to choose units of research which are as different as possible with regard to

extraneous variables. The basic logic is that differences cannot explain similarities.

What is exceptional for the MDSD is the focus on variables below the system level. The

task of the researcher is to test and attempt to confirm one particular finding within a

wide variety of systems. Echoing Popper (1959), the claim is that falsification rather

than verification is central for the progress of science. By conducting tests in a variety

of sub-systemic settings, the problem caused by too many variables and too few cases

is remedied.

A number of studies have had the ambition to combine a MSSD with a MDSD (e.g.

Berg-Schlosser & De Meur, 1994; Collier & Collier, 1991; De Meur & Berg-Schlosser,

1994, 1996 and, less explicitly, Linz & Stepan, 1996). Of all the studies that have

attempted to use the MSSD and MDSD, the studies by De Meur and Berg-Schlosser

provide the most sophistic applications of these research designs. In their studies of the

conditions for survival or breakdown of democracy in interwar Europe, they combine

two research designs, comparing on the one hand, systems that are Most Different With

Same Outcome (MDSO) and, on the other hand, systems that are Most Similar With

Different Outcome (MSDO). Furthermore, they develop a Boolean measure for assessing the degree of similarity and difference between their units of analysis.

Recent Methodological Developments

Ever since King et al. published their seminal work Designing Social Inquiry (1994) the

amount of literature pertaining to methodological issues has grown substantially.

Especially two methodological breakthroughs during the last decade have been important. The first one was the development of sophisticated software packages which now

allow us to conduct multi-level analyses fairly easily. The second one was Charles Ragins

(1987) invention of the so called Qualitative Case Analysis (QCA), which, in turn, was

subsequently improved by the introduction of fuzzy-set analysis (Ragin, 2000).

Now, there is a fundamental difference in the logic behind the MSSD described

above and the QCA/fuzzy-set approach. Whereas QCA/fuzzy-set is a case-oriented

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 391

method, the MSSD follows a strict variable-oriented approach. When making use of

MSSD, the ambition is to test the effect of an independent variable on the dependent

variable, while keeping extraneous variance constant. What is characteristic of the

QCA/fuzzy-set technique, on the other hand, is an ongoing interplay between theory

and data. Indeed, as Ragin (2000, p. 310) himself notes [f]uzzy sets are most useful as

tools of discovery. In other words, whereas MSSD aims at testing theories, the primary

goal by using QCA/fuzzy-set is to discover theories.

It is easy to reach the conclusion that multi-level analysis has made the MDSD obsolete. When making use of a MDSD, we first study variable interactions within different

systems and then compare the results obtained between the systems. If the results

differ, we turn to the system level (i.e. we introduce independent variables that denote

system-level characteristics). By the use of multi-level techniques it is possible to do

both things at the same time. This, however, does not mean that we should reject

MDSD as obsolete. Instead, I would argue that in comparative studies especially,

regression models using multi-level techniques should be built according to the logical

foundations of a most different systems approach. One could even go one step further

and argue that multi-level modelling makes it easier to apply the MDSD logic in

comparative research. In fact, multi-level modelling was exactly what Przeworski and

Teune (1970, p. 72) desired 40 years ago: [w]hat we need in comparative research

are statistical techniques that would allow the control variable to be measured at a level

different from the two variables that are tested.

The advantage of multi-level modelling is that it makes it easier to shift the level of

analysis. We no longer have to exhaust the variables at the subsystem level before turning to the next level of analysis. Instead, we can study effects of variables at both analytical levels at the same time. However, the field of comparative politics is special, in the

sense that the number of countries is limited and many features residing at the country

level go hand in hand. If we start introducing variables residing at the system (country)

level into the model, we very soon have to confront the problem of multicollinearity at

the systemic level. To take an example: A researcher who wants to explain the attitudes

towards the death penalty with regard to the level of education and system-level variables such as democracy, Christian dominance, and a historic absence of slavery will

soon discover that it is a hopeless enterprise since Christianity, democracy and a

historic absence of slavery go hand in hand (Anckar, 2004, pp. 9798).

In order to cope with this problem, we need to apply the principle of falsification

that the MDSD is built on. Since the inclusion of many system-level variables makes

the regression models unstable, the ambition should be to exclude as many system-level

variables as possible from the regression models. This is done by studying interactions

between independent and dependent variables in as varying contexts as possible. The

principle is easy: when an association between the independent and the dependent

variable is found in two varying contexts, the more the analytical contexts differ in

terms of systemic factors, the higher the number of systemic variables that can be disregarded from the regression model. If, for instance, it can be proven that a high level of

education is associated with a negative view of the death penalty in Sweden, Zimbabwe

and the United Arab Emirates we can disregard the system level variables democracy,

392

C. Anckar

Christian dominance and historic absence of slavery since these features vary between

the three countries.

In the following section I argue that, in general, the fields of application of the

MSSD and MDSD have been unnecessarily restricted in the literature on social science

methodology. I further show that the application of MSSD and MDSD is dependent

on: (1) whether or not variable interactions are studied at a systemic level or at a subsystemic level; (2) whether we use a deductive or inductive research strategy and (3)

whether or not we operate with a constant or varying dependent variable.

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

Level of Analysis

The MSSD is particularly useful in cases where we are interested in variables at a

systemic level. Similar systems designs require an a priori assumption about the

level of social systems at which the important factors operate. Once a particular design

is formulated, assumptions concerning alternative levels of systems cannot be considered (Przeworski & Teune, 1970, p. 36). As we have seen, the MDSD is used when the

variables are at a sub-systemic level. Of course, since all social interactions do not

reside at the sub-systemic level, Przeworski and Teune argue that the system level

must be accounted for as well. However, their basic argument is that the system level

enters the research design only if and when the analyses within systems show that

different variable associations exist within different systems (Przeworski & Teune,

1970, p. 35). The most serious limitation of the MDSD seems to be that it can only be

applied in situations where the dependent variable resides at a sub-systemic level. In

other words, independent variables can be measured at all levels but the dependent

variable should reside at a sub-systemic level. Needless to say, this qualification makes

MDSD inapplicable for a great number of comparative studies.

Deduction or Induction

There are two ways to approach a research problem. Either we focus on the independent variable or on the dependent variable. When the main research interest is on the

independent variable the research question is expressed in the sentence Does X affect

Y? We are, in other words, not primarily concerned with explaining all the variation in

the dependent variable, i.e. accounting for the explanatory value of every single explanatory factor. Instead, we have the ambition to establish whether or not there is a causal

relation between one specific independent variable and the dependent variable. When

our primary focus is on the dependent variable, the research process naturally begins

with a research question formulated in the sentence What explains Y? A research

question formulated in this manner indicates that we have the ambition to discover

the relevant independent variable(s).

Now, the former strategy requires, by necessity, a deductive approach. The independent variable has been identified in the beginning of the research process by means

of theoretical reasoning. Likewise, when we depart from the dependent variable it is

natural to apply an inductive research strategy. An existing theoretical framework is not

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 393

a requirement, but instead the researcher is advised to enter the quest for the independent variable(s) with an open mind. However, an inductive approach is not an absolute

requirement. We can also attempt to identify all plausible determinants of the dependent variable by means of theoretical reasoning. In other words, a Does X affect Y?

question is always answered by using deduction and a What explains Y? question is

answered either by means of deductive or inductive reasoning.

In practice, the difference between the two strategies is likely to become blurred. For

instance, if we wish to assess the effect of X on Y we must control for a number of other

variables. It makes little sense to conduct only bivariate analyses. In a regression analysis, the position of the key independent variable is not different from the position of

the control variables since we measure the effects of each independent variable on the

dependent variable at constant values on all other independent variables. In other

words, we cannot assess the impact of one independent variable without assessing the

impact of all other independent variables included in the regression model. When

applying a MSSD, on the other hand, the position of the key variable of interest is

different from that of the control variables, since all control variables are kept constant

whereas only the key independent variable is allowed to vary.

Furthermore, no study is 100% inductive since we can never pay regard to all possible explanations of a phenomenon. To some extent, we are guided by a preconception

of the phenomenon which allows us to disregard a number of potential explanations.

Even though very little previous research exists in a specific area of research we usually

have a good idea in which settings we should look for the plausible explanations. The

dividing line between these two strategies, then, is anything but sharp. However, as we

shall see, for the purpose of designing a study according to the principles of MSSD and

MDSD, it is necessary to theoretically distinguish between a deductive and an inductive

approach to a research problem.

The Dependent Variable

When making use of the MSSD, we choose systems which differ with respect to the

independent variable whereas all contesting variables are kept constant. The requirement that all contesting variables are kept constant seems to presuppose that the theoretical framework from which we depart is fairly well developed. As we have seen, in

practice, this requirement can be remedied by using countries which are geographically

and culturally close to each other. In this way, most of the plausible explanatory factors

are automatically constant and cannot intervene in the relation between the independent and the dependent variables. Nevertheless, given the limited number of countries, it is impossible to find cases where all background variables are constant. Thus,

any MSSD model is, as Przeworski and Teune (1970, p. 34) put it, likely to overdetermine the dependent variable.

One major difference between the MSSD and the MDSD appears to be that whereas

the former method is concerned with the independent variable, the latter focuses on the

dependent variable. When examining the literature on the comparative method we

sometimes run across statements suggesting that a MDSD necessitates a constant

394

C. Anckar

dependent variable. In other words, the phenomenon under investigation should not

vary (e.g. Landman, 2003, pp. 2934; Sartori, 1991, p. 250). This appears to be the most

serious weakness of the MDSD. The research strategy of operating with a constant

dependent variable is an issue that is extremely controversial and open for an ongoing

debate in the literature since it only allows the researcher to identify the necessary conditions of a phenomenon (e.g. Dion, 1998; King et al., 1994, pp. 129132, pp. 147149).

However, as will be shown momentarily, the question whether or not a MDSD presupposes a constant dependent variable is totally dependent on the research design.

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

MSSD and MDSDWhen to Use and How to Use

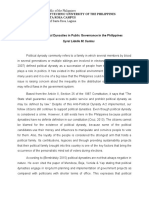

The discussion conducted above has focused on three essential distinctions which are

relevant when discussing the applicability of MSSD and MDSD: (1) systemic level vs. subsystemic level; (2) deduction or induction and (3) constant or varying dependent variable.

The combination of these dimensions is essential for how the MSSD and the MDSD can

and should be used in comparative research. Figure 1 sums up the discussion.

First, let me focus on MDSD and its requirement that the dependent variable is

constant. This feature of MDSD is sometimes mentioned in the literature on comparative method. At the same time, it is worth emphasizing that a reading of Przeworski

and Teune does not support the conclusion that a MDSD requires a constant dependent variable. To be fair, however, it is easy to see why many authors have interpreted

Przeworski and Teune this way. Przeworski and Teune (1970, p. 35) give two examples

of how the MDSD can be understood: If the rates of suicide are the same among the

Zuni, the Swedes and the Russians, those factors that distinguish these three societies

are irrelevant for the explanation of suicide. From this example it is evident that the

dependent variable (the rate of suicide) should not vary across the three different

systems. However, the authors continue with another example: If education is

Figure 1

How to use MSSD and MDSD in comparative research.

Formulation of

Does X affect Y?

research problem

What explains Y?

Consequence of

formulation of

research problem

Deduction

Induction

Comparative

research design

MSSD

MDSD

MDSD

MSSD

Constant

Varies

Varies

Constant

Extraneous

variance

Level of

analysis

system

(subsystem)

system subsystem

system subsystem

system (subsystem)

Dependent

variable

not considered (not considered) constant not considered

constant

constant

Figure 1 How to use MSSD and MDSD in comparative research.

varies

(varies)

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 395

positively related to attitudes of internationalism in India, Ireland and Italy, the differences among these countries are unimportant in explaining internationalist attitudes.

In this example, the dependent variable does not necessarily have to be constant across

the three systems. Instead, what is of importance is the fact that the pattern of the causal

relation is the same within the three systems (see especially Przeworski & Teune, 1970,

pp. 7685). It is important to note that in both cases, the logic follows what De Meur

and Berg-Schlosser (1994, 1996) has labelled MDSO. The only difference is that in the

first mentioned example, a variable is constant across cases whereas in the second

example a relationship between variables is constant across cases.

When using the MDSD in a deductive study it is preferable that the dependent variable is not considered prior to the research problem. However, if the research question

is inductive (as could be the case in the example with the Zuni, the Swedes and the

Russians) it is easy to see why the dependent variable must be constant. If the units of

analysis differ with regard to the dependent variable and are also dissimilar with regard

to most of the plausible determinants, it is impossible to identify the relevant explanatory variable(s).

What about MSSD then? We have seen that in a pure MSSD, the independent variable should vary, whereas values on the dependent variable are of no interest in the

beginning of the research process. It appears, then, as if a MSSD can be used exclusively

in situations where the research problem is formulated in the sentence Does X affect

Y? and consequently a deductive approach is used. This, however, is not true. Both in

principle and in practice, it is possible to use the MSSD in an inductive study, but this

presupposes that we begin the research process by focusing on the dependent variable.

We then secure variation on the dependent variable among systems that appear to be

very much alike (see Ragin, 1987, p. 47). The works by De Meur and Berg-Schlosser

constitute an excellent illustration of such a research design. They label this form of

investigation most similar cases with a different outcome (De Meur & Berg-Schlosser,

1996, p. 425). Their approach is highly inductive in that they make use of not less than

63 independent variables.

One could argue that a pure MSSD requires that theory guides the choice of both the

independent variables that are allowed to vary and the extraneous variables that are to

be kept constant. When induction is used in its purest form we do not know which

extraneous variables are to be kept constant. Instead, we are keeping as many plausible

extraneous variables as possible constant by choosing countries that are (or appear to

be) similar. Since similarities cannot explain differences, the goal is to find variables

that differ. The relevant independent variable is arrived at by means of falsification and

the method used is identical to Mills (1874, p. 280) method of difference (for an illustrative discussion on how the MSSD and the MDSD can be mirrored with regard to the

structure of the dependent variable and to Mills methods, the reader is referred to

Murray Faure 1994, pp. 316318).

Let me then focus on the level of analysis. Previously it was argued that the MSSD is

suitable for the systemic level and the MDSD should be applied when studying variable

interactions at a sub-systemic level. Evidently, the logic of the MSSD can be applied at

the lowest possible analytical level as well. Thus, at least in principle, it is possible to

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

396

C. Anckar

study if income is related to voting behaviour by choosing individuals which differ with

regard to income but show a resemblance on a number of background characteristics.

(Of course, since the number of cases is always high at the individual level, we would

prefer to use regression analysis in this example). However, the very notion of comparative politics requires that we make cross-national observations. This requirement

disqualifies the use of MSSD at the sub-systemic level at least in comparative research.

Finally, we should consider the applicability of MDSD at the systemic level. Here, I

would argue that the logic of MDSD can perfectly well be used in situations where the

dependent variable resides at the country level as well. Indeed, when trying to find examples of studies where the MDSD has been used authors generally refer to Theda Skocpols

States and Social Revolutions (1979), where the dependent variable, the occurrence of

major revolutions, resided at the systemic level. It is easy to agree with Sartoris (1991,

p. 250) assessment that the requirement that the MDSD must operate at a sub-systemic

level is a differentiation open to question. The MDSD can easily be used across systems,

for instance, by studying why the level of democracy is high in Finland, Botswana, Costa

Rica and Palau. However, if a MDSD is applied at a systemic level my earlier conclusion

that a MDSD does not presuppose a constant dependent variable must be qualified.

When we use a MDSD at a systemic level the dependent variable must, by necessity, be

constant. This is so, because if the phenomenon we wish to explain resides at the systemic

level, we cannot identify the explanatory factors across different countries unless we look

for similarities in these dissimilar systems. For instance, if we wish to test the assumption

that modernization brings about democracy we cannot test this ambition by comparing

Sweden and Afghanistan. True, the two countries differ with regard to the dependent

variable and the independent variable but they also differ with regard to many other

plausible determinants of democracy, e.g. religion, and civil society.

Thus, whether we use the MDSD with an inductive or a deductive strategy at the

systemic level, the ambition is to find common denominators across systems and the

research method is identical to Mills (1874, pp. 278280) method of agreement. De

Meur & Berg-Schlosser (1994, p. 198) use the expression most different systems with

the same outcome to illustrate this design (see also Murray Faure, 1994, pp. 316318).

The only difference between a deductive and an inductive MDSD at the system level is

that when we use the MDSD with a deductive strategy at a systemic level, our ambition

is to study if the independent variable is present in all cases. When using an inductive

strategy, on the other hand, we do not have an a priori notion of the relevant explanatory variable, and our ambition is to look for the determinant of the dependent variable

with an open mind.

The Applicability of Mills Methods of Difference and Agreement in the Social

Sciences

Of the eight models of research design that emerge in Figure 1, all but one (MDSD, in

deductive studies at the sub-systemic level) make use of Mills methods of difference or

agreement. These methods have been debated extensively during the last decades.

Lieberson (1991) has argued, among other things, that the methods cannot cope with

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 397

probabilistic assumptions and measurement errors. This assessment, however, is unfair

to small-N analyses. A single exception from a rule does not lead us to reject a hypothesis in the social sciences and nobody would even consider demanding that a quantitatively oriented researcher who finds that all cases are not situated along the regression

line rejects his or her hypothesis (Goertz, 2005). Also, as shown by Ragin (2000), it is

perfectly possible to make use of probabilistic criteria when assessing necessity and

sufficiency and the same logic can consequently be applied to MSSD and MDSD. In

fairness, however, we cannot escape the fact that a case that contradicts a general rule

is more problematic the smaller the number of cases.

Savolainen (1994, pp. 12201221) disproves another point of criticism raised by

Lieberson (1991, pp. 312314), namely that Mills methods do not cope with interaction effects. Here it is worth emphasizing that the method of difference allows for the

creation of interaction terms. For instance, suppose we believe that democracy is

enhanced by insularity and British colonial heritage. However, we expect that neither

of these variables in themselves bring about democracy. Instead, the combination of

British colonial heritage and insularity is crucial for democracy. In this case we would

simply form a category consisting of those countries only which meet both of these

criteria (British colonial heritage and insularity).

Admittedly, it is difficult to discover interaction effects with Mills methods. In the

following example (Figure 2) we have the ambition to study if insularity is related to a

democratic form of government in an African context, using the Mills method of difference.1 Two control variables are introduced: British colonial heritage and Christianity

(> two-thirds Christians).

Based on these results, we would reach the conclusion that insularity is associated with

a democratic form of government. However, it might well be that the real explanation for

democracy is a combination of insularity and colonial heritage, a combination of insularity and Christianity, or a combination of insularity, colonial heritage and Christianity.

The independent effect of insularity on democracy can only be assessed by including

more cases, which allow us to keep constant British colonial heritage and Christianity at

Figure 2

Problem of discovering interaction effects in a MSSD.

Seychelles

Swaziland

Insularity

yes

no

British colonial heritage

yes

yes

Christianity

yes

yes

------------------------------------------------------------------Democracy

yes

Figure 2 Problem of discovering interaction effects in a MSSD.

no

398

different values. This is illustrated in Figure 3. When including the first matched pair,

namely the cases of Cape Verde and Rwanda into the analysis, the result is confirmed in

countries without a British colonial heritage, which means that we can rule out the insularity/colonial heritage combination as an explanation of democracy. In the next step,

we introduce the pair Mauritius and Somalia into the analysis whereby the insularity/

Christianity combination is falsified. Finally, we introduce the pair Madagascar and

Chad by which we can rule out the possibility that insularity in combination with either

colonial heritage or Christianity is required for democracy to emerge.

When applying the method of agreement our ambition is only to identify necessary

causes of the dependent variables. If we succeed in identifying a single necessary condition for the outcome then it follows logically that this variable in itself is necessary for

generating the outcome regardless of how it interacts with the control variables (Ragin,

2000, pp. 100101). The problem of identifying interaction effects arises when we find

more than one necessary cause to the phenomenon under study. In these cases too, the

researcher should try to include more cases in order to find out whether or not the

respective variables are capable of generating the outcome on their own or only in

combination with each other.

Admittedly, the limited number of countries places restrictions on the extent to

which we can include new countries in the research design in the manner described in

Figure 3. In most situations when we apply the MSSD and MDSD the number of cases

is limited and we have to face the problem of causal complexity. In other words, it is

impossible to account for all possible combinations of the independent variables.

Suppose, for instance, that we have the ambition to identify the necessary conditions of

the use of the death penalty. Using the method of agreement, we would then identify a

common explanatory cause, say, an autocratic form of government. The countries

included in the study vary in a number of characteristics that could constitute plausible

determinants of the use of the death penalty: level of crime, history of slavery, dominating

religion, socioeconomic development, level of corruption, conflict intensity etc. (Anckar,

2004). However, an examination of the cases would reveal, among other things, that

none of the authoritarian countries making use of the death penalty exhibited a high

Figure 3

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

C. Anckar

Coping with Interaction Effects in a MSSD.

Figure 3 Coping with Interaction Effects in a MSSD.

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 399

level of socioeconomic development, no history of slavery, a low level of corruption, a

low level of conflict intensity and Taoism as dominant religion. Consequently, we do

not know if this particular combination also would generate a state which makes use of

capital punishment or not.2,3

However, comparativists will never overcome the problem of causal complexity

regardless of which method they use. We simply cannot create countries that meet

the requirements for experimental designs and the problem of social complexity is by

no means unique for the MSSD or MDSD approach. Results reached at by means of

conventional multivariate regression models suffer from the same shortcomings,

since there are vast areas of the vector space that lack empirical instances (Ragin,

2000, pp. 198199, pp. 312313). The greatest advantage with the MSSD and MDSD

is the possibility to exclude contesting variables from the analysis by carefully matching the cases according to the principles of the two methods.

The shortcomings ascribed to MSSD and MDSD usually do not arise as a consequence of the logic of the methods but rather by the small number of cases included in

these studies. However, since we cannot manipulate the number of independent countries, we have to make the best out of the methods that are available. The central feature

when applying the MSSD and the MDSD is the ambition to isolate the explanatory

value of the independent variable as much as possible. This is done by choosing countries that are as similar as possible on the background variables (in a MSSD) or as

dissimilar as possible (MDSD). The selection of cases is done only with regard to these

principles.

An alternative view is advocated by proponents of the so called case oriented

approach, who suggest that we should not focus on variable interactions in social

research. For instance, Abbot (1988; 1992) has pointed out that quantitatively oriented

social scientists tend to fail to consider the fact that causal relations may take different

forms in different cases and do not pay enough attention to the actual processes

preceding the outcome (for a similar argument see Byrne, 2002, p. 2943).

These arguments are well-founded and should not be dismissed lightly. I fully agree

that establishing causal variable interactions across cases is a tricky business in social

sciences. The other side of the coin, however, is that we need variables in cases where

the ambition is to assess the general validity of a theoretical statement. Having said

that, it should be acknowledged that within the field of comparative politics, where the

number of cases is limited, the distinction between case-oriented studies and variable

oriented ones is often blurred (e.g. Ragin, 1987, pp. 6984). In this respect, the MSSD

and MDSD actually function as bridge builders between case oriented and variable

oriented researchers. The status of the method of agreement in particular is unclear,

since it is widely used by case oriented researchers, but still aims at identifying

commonalities across cases that vary with regard to the control variables. The MSSD,

with its focus on securing variation on the independent variable while keeping extraneous variation constant, is closer to the traditional variable oriented design.

However, since we operate with a limited number of cases, it is impossible to lose sight

of the case-specific peculiarities of the countries. Accordingly, cases are never reduced

to data spots in a diagram, a risk which is inherent in statistical large-N analyses.

400

C. Anckar

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

Conclusion

Although new analytical tools have emerged during the last decades, it is easy to predict

that the MSSD and the MDSD will continue to play an important role for social scientists engaged in comparative research. The MSSD and the MDSD can be used in a

number of ways, depending on how the research task is designed. Authors are therefore

advised to fully take advantage of these possibilities of MSSD and MDSD. The biggest

advantage with the MSSD and MDSD lies in their ability to eliminate a large number

of potentially relevant explanatory variables from further analysis. By carefully matching a small number of cases across a wide range of potential explanatory variables we

can exclude a wide range of variables from further analysis. The outstanding examples

in the literature are the studies by De Meur and Berg-Schlosser (1994, 1996), who used

not less than 63 variables and 18 cases when accounting for the determinants of authoritarianism, fascism and democracy in interwar Europe.

Notes

[1]

1

[2]

[3]

2

Lieberson (1991, p. 312) constructs an often quoted example involving car accidents to illustrate this.

I am grateful to an anonymous referee for pointing this out to me by using another example.

Lieberson (1991, pp. 313314; 1994, pp. 12331235) also criticises Mills methods for not

being able to deal with multiple causes. When using the method of agreement, this is perfectly

true and consequently the ambition can only be to identify necessary causes of a phenomenon.

Regarding the MSSD, Liebersons (1994, p. 1235) example does not meet the requirements of

a MSSD, since the background variables are not kept constant. In a pure MSSD, we would

secure variation on the independent variable and keep constant all other plausible explanatory

variables. If we also want to test effects of another independent variable this must be done by

choosing another set of countries, whereby it is possible to secure variation on the new independent variable and keep all other plausible determinants constant. The solution to the

problem of identifying multiple causes is the same that applied to identifying interaction

effects, i.e. to introduce new cases which allow us to keep constant background variables at

different values.

References

Abbott, A. (1988). Transcending general linear reality. Sociological Theory, 6, 169186.

Abbott, A. (1992). What do cases do? Some notes on activity in sociological analysis. In C. Ragin &

H. S. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry (pp. 5382).

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anckar, C. (2004). Determinants of the death penalty: A comparative study of the world. London:

Routledge.

Bartolini, S. (1993). On time and comparative research. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 5, 131167.

Berg-Schlosser, D., & De Meur, G. (1994). Conditions of democracy in interwar Europe: A Boolean

test of major hypotheses. Comparative Politics, 3, 253279.

Byrne, D. (2002). Interpreting quantitative data. London: Sage.

Collier, R. B., & Collier, D. (1991). Shaping the political arena: Critical junctures, the labor movement,

and regime dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

De Meur, G., & Berg-Schlosser, D. (1994). Comparing political systems: Establishing similarities and

dissimilarities. European Journal of Political Research, 26, 193219.

Downloaded by [University of Oslo] at 05:55 29 September 2015

International Journal of Social Research Methodology 401

De Meur, G., & Berg-Schlosser, D. (1996). Conditions of authoritarianism, fascism, and democracy

in interwar Europe: Systematic matching and contrasting of cases for Small N analysis.

Comparative Political Studies, 29, 423468.

Dion, D. (1998). Evidence and inference in the comparative case study. Comparative Politics, 30,

127145.

Goertz, G. (2005). Necessary condition hypotheses as deterministic or probabilistic: Does it matter?

Qualitative Methods: Newsletter of the American Political Science Association Organized Section

on Qualitative Methods, 3, 2227.

King, G., Keohane, R., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative

research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Landman, T. (2003). Issues and methods in comparative politics: An introduction (2nd ed.). London &

New York: Routledge.

Lieberson, S. (1991). Small Ns and big conclusions: An examination of the reasoning in comparative

studies based on a small number of cases. Social Forces, 70, 307320.

Lieberson, S. (1994). More on the uneasy case for using Mill-type methods in Small-N comparative

studies. Social Forces, 72, 12251237.

Lijphart, A. (1971). Comparative politics and the comparative method. American Political Science

Review, 65, 682693.

Linz, J., & Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe,

South America, and post-communist Europe. Baltimore, MD & London: The Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Meckstroth, T. (1975). Most different systems and Most similar systems: A study in the logic of

comparative inquiry. Comparative Political Studies, 8, 132157.

Mill, J. S. (1874). System of logic. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Murray Faure, A. (1994). Some methodological problems in comparative politics. Journal of

Theoretical Politics, 6, 307322.

Peters, B.G. (1998). Comparative politics: Theory and methods. Houndmills: Palgrave.

Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Basic Books.

Przeworski, A., & Teune, H. (1970). The logic of comparative social inquiry. New York: John Wiley.

Ragin, C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Ragin, C. (2000). Fuzzy-set social science. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sartori, G. (1991). Comparing and miscomparing. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 3, 243257.

Savolainen, J. (1994). The rationality of drawing big conclusions based on small samples: In defense

of Mills Methods. Social Forces, 72, 12171224.

Skocpol, T. (1979). States and social revolutions. A comparative analysis of France, Russia and, China.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skocpol, T. (1984). Emerging agendas and recurrent strategies in historical sociology. In T. Skocpol

(Ed.), Visions and methods in historical sociology (pp. 356391). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

You might also like

- Pedro L. Baldoria (1910-1966)Document2 pagesPedro L. Baldoria (1910-1966)Ronald Larracas Jr.100% (1)

- ARTICLE XVII - Compiled Case Digests and BAR Questions (Complete)Document3 pagesARTICLE XVII - Compiled Case Digests and BAR Questions (Complete)Julo R. TaleonNo ratings yet

- China 21st Century SuperpowerDocument3 pagesChina 21st Century SuperpowerZahra BhattiNo ratings yet

- The Future of Development AdministrationDocument10 pagesThe Future of Development AdministrationmelizzeNo ratings yet

- Classical PluralismDocument3 pagesClassical PluralismShiela Krystle MagnoNo ratings yet

- Principle of Justice (Updated)Document2 pagesPrinciple of Justice (Updated)SYOXISSNo ratings yet

- Debate Federalism (New 2)Document3 pagesDebate Federalism (New 2)PhantasiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Human RightsDocument15 pagesChapter 1 Human RightsiamysaaahhhNo ratings yet

- The Methodological Problems of Filipino PhilosophyDocument21 pagesThe Methodological Problems of Filipino PhilosophyBabar M. SagguNo ratings yet

- Political Law NotesDocument10 pagesPolitical Law NotesMish Alonto100% (2)

- Constitutional Law Legal Standing Alan Paguia Vs Office of The Pres G.R. No. 176278 June 25, 2010Document3 pagesConstitutional Law Legal Standing Alan Paguia Vs Office of The Pres G.R. No. 176278 June 25, 2010JoannMarieBrenda delaGenteNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument13 pagesThesisJoseph DegamoNo ratings yet

- Mendiola Massacre Supreme Court RulingDocument7 pagesMendiola Massacre Supreme Court RulingMidzfar OmarNo ratings yet

- Esteve y Schuster 2019 Motivating Public Employees - Extracto PDFDocument10 pagesEsteve y Schuster 2019 Motivating Public Employees - Extracto PDFcarmonavgNo ratings yet

- Vol 6 Issue 21Document426 pagesVol 6 Issue 21Arnulfo Pecundo Jr.No ratings yet

- Meaning and scope of public administrationDocument6 pagesMeaning and scope of public administrationAzizi Wong WonganNo ratings yet

- BicameralismDocument3 pagesBicameralismJaeRose60No ratings yet

- Introduction To Political Theory - PlanDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Political Theory - PlanLinda ChenNo ratings yet

- Consti Case Digest (Fundamental Powers of The State)Document28 pagesConsti Case Digest (Fundamental Powers of The State)Vhe CostanNo ratings yet

- Role of Lawyers in Legal EducationDocument13 pagesRole of Lawyers in Legal EducationAnimesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Manila re-implements curfew for minors under 40-character ordinanceDocument4 pagesManila re-implements curfew for minors under 40-character ordinanceSophie BaromanNo ratings yet

- Castillo - Federalism and Its Potential Application To The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument193 pagesCastillo - Federalism and Its Potential Application To The Republic of The Philippinessolarititania100% (1)

- Tomlinson Critiques "Third WorldDocument3 pagesTomlinson Critiques "Third WorldMarley RayNo ratings yet

- C-4 Consumer Behavior and Utility MaximizationDocument10 pagesC-4 Consumer Behavior and Utility MaximizationTata Digal RabeNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Quarantine on Mental HealthDocument3 pagesThe Impact of Quarantine on Mental HealthMarco RegunayanNo ratings yet

- Pros and cons of Federalism in the PhilippinesDocument1 pagePros and cons of Federalism in the PhilippinesFortes Roberto GajoNo ratings yet

- Unraveling Political Dynasties in the PhilippinesDocument8 pagesUnraveling Political Dynasties in the PhilippinesSyrel SantosNo ratings yet

- Leal Vs IACDocument7 pagesLeal Vs IACLady Paul SyNo ratings yet

- Lagman v. MedialdeaDocument2 pagesLagman v. MedialdeaShiela BrownNo ratings yet

- Mendoza, J.: Lucita Estrella Hernandez, Petitioner vs. Court of Appeals and Mario C. Hernandez, RespondentsDocument6 pagesMendoza, J.: Lucita Estrella Hernandez, Petitioner vs. Court of Appeals and Mario C. Hernandez, RespondentsmjoimynbyNo ratings yet

- Gendering The State PerformativityDocument6 pagesGendering The State PerformativityHenrick YsonNo ratings yet

- Ra 9710Document26 pagesRa 9710WeGovern InstituteNo ratings yet

- Banat V ComelecDocument51 pagesBanat V ComelecEric RamilNo ratings yet

- The Bangsamoro Peace ProcessDocument2 pagesThe Bangsamoro Peace ProcessBeatrice BaldonadoNo ratings yet

- 3 de La Llana v. AlbaDocument12 pages3 de La Llana v. AlbaGlace OngcoyNo ratings yet

- Power Authority and PoliticsDocument23 pagesPower Authority and PoliticsMeetali UniyalNo ratings yet

- CA 327 audit decisions and appealsDocument1 pageCA 327 audit decisions and appealsAquiline ReedNo ratings yet

- YOUTH ACT NOW AGAINST CORRUPTION Abolish The Pork Barrel SystemDocument1 pageYOUTH ACT NOW AGAINST CORRUPTION Abolish The Pork Barrel SystemNational Union of Students of the PhilippinesNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 On Public AdministrationDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 On Public AdministrationLukasNo ratings yet

- A Baby Thesis On Awareness On PPA's of SantiagoDocument47 pagesA Baby Thesis On Awareness On PPA's of SantiagoJohn Michael BanuaNo ratings yet

- Functional School of Jurisprudence 2Document1 pageFunctional School of Jurisprudence 2Jani MisterioNo ratings yet

- Justice Revenge EssayDocument2 pagesJustice Revenge Essayapi-334294741No ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Machiavelli's Argument in The PrinceDocument5 pagesCritical Analysis of Machiavelli's Argument in The PrinceHaneen AhmedNo ratings yet

- GR No. L-26712-16 Social Security Commission vs petitionersDocument6 pagesGR No. L-26712-16 Social Security Commission vs petitionersAbigail DeeNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law - Lesson 2 (Landscape)Document7 pagesConstitutional Law - Lesson 2 (Landscape)James Ibrahim AlihNo ratings yet

- Case 1Document7 pagesCase 1Jefferson A. dela CruzNo ratings yet

- IGR Concept of InterdependenceDocument5 pagesIGR Concept of InterdependenceZhanice RulonaNo ratings yet

- Eugenio v. DrilonDocument1 pageEugenio v. DrilonJashen TangunanNo ratings yet

- Nature of Political Science - Why Is It A Social Science?Document3 pagesNature of Political Science - Why Is It A Social Science?awstikadNo ratings yet

- Publication Requirement for Laws to Ensure Due ProcessDocument6 pagesPublication Requirement for Laws to Ensure Due ProcessElieNo ratings yet

- Enforcing The Right To Health:: Batstateu - Pablo Borbon Campus, Batangas City, Philippines, 4200Document12 pagesEnforcing The Right To Health:: Batstateu - Pablo Borbon Campus, Batangas City, Philippines, 4200NONIEBELL MAGSINONo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on first writ of amparo caseDocument46 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court rules on first writ of amparo casepreiquencyNo ratings yet

- NACOCO Not a Government EntityDocument1 pageNACOCO Not a Government EntityHenteLAWcoNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Engineering Discourse Analysis FinalDocument8 pagesMechanical Engineering Discourse Analysis Finalapi-315731194No ratings yet

- What Is Political TheoryDocument2 pagesWhat Is Political TheoryShriya OjhaNo ratings yet

- IR 231 Introduction To International Relations I - 1Document8 pagesIR 231 Introduction To International Relations I - 1Jeton DukagjiniNo ratings yet

- Sociological Imagination and LawDocument15 pagesSociological Imagination and Lawshivam shantanuNo ratings yet

- On The Applicability of The Most Similar Systems Design and The Most Different Systems Design in Comparative ResearchDocument14 pagesOn The Applicability of The Most Similar Systems Design and The Most Different Systems Design in Comparative ResearchAFONSONo ratings yet

- E-Tailing/electronic Retailing Dissertation PresentationDocument28 pagesE-Tailing/electronic Retailing Dissertation PresentationSatyabrata SahuNo ratings yet

- ML Unit 2Document21 pagesML Unit 22306603No ratings yet

- Causal Research Design: ExperimentationDocument35 pagesCausal Research Design: ExperimentationBinit GadiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Multivariate Analysis TechniquesDocument58 pagesChapter 13 Multivariate Analysis TechniquesSharon AnchetaNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Study To Understand Consumer Satisfaction Towards Online Food Delivery Application With Specific Reference To Swiggy in Indian ContextDocument14 pagesAn Empirical Study To Understand Consumer Satisfaction Towards Online Food Delivery Application With Specific Reference To Swiggy in Indian ContextJyoti JNo ratings yet

- Mixed CostDocument4 pagesMixed CostPeter WagdyNo ratings yet

- Employee Involvement and Organizational Performance: Evidence From The Manufacturing Sector in Republic of MacedoniaDocument6 pagesEmployee Involvement and Organizational Performance: Evidence From The Manufacturing Sector in Republic of MacedoniaPutrii AmbaraNo ratings yet

- Bok:978-3-319-06007-1yearbook of Corpus Linguistics and PragmaticsDocument341 pagesBok:978-3-319-06007-1yearbook of Corpus Linguistics and Pragmaticsابو محمدNo ratings yet

- Final ReportDocument18 pagesFinal Reportsrikanth3088No ratings yet

- BAN 602 - Project4Document5 pagesBAN 602 - Project4Michael LipphardtNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology Assignment - NMIMS GlobalDocument4 pagesResearch Methodology Assignment - NMIMS GlobalAmbika MamNo ratings yet

- Friendship Quality Emotion Understanding and Emotion Regulation of Children With and Without Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or SpecificDocument18 pagesFriendship Quality Emotion Understanding and Emotion Regulation of Children With and Without Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or SpecificÁgata Rodrigues da CâmaraNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Board Composition On The Level of ESG Disclosures in GCC CountriesDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Board Composition On The Level of ESG Disclosures in GCC CountriesImtiaz BashirNo ratings yet

- Introduction to KNN Classification with Python Implementation (40Document125 pagesIntroduction to KNN Classification with Python Implementation (40Abhiraj Das100% (1)

- A Linear Regression Approach To Predicting Salaries With Visualizations of Job Vacancies: A Case Study of Jobstreet MalaysiaDocument13 pagesA Linear Regression Approach To Predicting Salaries With Visualizations of Job Vacancies: A Case Study of Jobstreet MalaysiaIAES IJAINo ratings yet

- Table of Contents for Automotive Industry Outsourcing ReportDocument28 pagesTable of Contents for Automotive Industry Outsourcing ReportMohd Yousuf MasoodNo ratings yet

- Cursus Advanced EconometricsDocument129 pagesCursus Advanced EconometricsmaxNo ratings yet

- Using EXCEL For Statistical AnalysisDocument47 pagesUsing EXCEL For Statistical AnalysistrivzcaNo ratings yet

- Internal Marketing Builds Business CompetenciesDocument28 pagesInternal Marketing Builds Business Competencieskristina dewiNo ratings yet

- DhakalDinesh AgricultureDocument364 pagesDhakalDinesh AgriculturekendraNo ratings yet

- Spss ReviewerDocument5 pagesSpss ReviewerJanine EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- UoG Econometrics NotesDocument213 pagesUoG Econometrics NotesGedefaw AbebeNo ratings yet

- Work-Life Balance - Weighing The Importance of Work-Family and Work-Health Balance - PMCDocument28 pagesWork-Life Balance - Weighing The Importance of Work-Family and Work-Health Balance - PMCShubhangi MamgainNo ratings yet

- Name: Muhammad Hamza Ghouri Roll No # 15056 Course: Business Research MethodsDocument7 pagesName: Muhammad Hamza Ghouri Roll No # 15056 Course: Business Research MethodsSYED ABDUL HASEEB SYED MUZZAMIL NAJEEB 13853No ratings yet

- Assignment 2: Experimental Design: DescriptionDocument8 pagesAssignment 2: Experimental Design: DescriptionGradeUp Education InstituteNo ratings yet

- Optimisation and Prediction of The Weld Bead Geometry of A Mild Steel Metal Inert Gas WeldDocument11 pagesOptimisation and Prediction of The Weld Bead Geometry of A Mild Steel Metal Inert Gas WeldSam SadaNo ratings yet

- QT Chapter 4Document6 pagesQT Chapter 4DEVASHYA KHATIKNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - MAS IntroductionDocument9 pagesChapter 1 - MAS Introductionchelsea kayle licomes fuentesNo ratings yet

- Level of MeasurementsDocument22 pagesLevel of MeasurementsAthon AyopNo ratings yet

- Analysis Data Model v2.1Document41 pagesAnalysis Data Model v2.1ahermayursomnath.phe22No ratings yet