Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Portal

Uploaded by

Rishabh BaroniaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Portal

Uploaded by

Rishabh BaroniaCopyright:

Available Formats

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

the international journal of

computer game research

home

about

Michael Burden

Michael Burden (BSc,

MA) finished his thesis

on the cultural impact of

algorithms in video

games and web sites

while writing this paper.

He has previously

worked for two video

game companies (the

defunct Igamol, and

Ubisoft), as well as

authoring video games

for research, and is now

performing analytics at

BioWare. His one-yearold son is already trying

to join his video game

sessions.

michael.burden@gmail.com

Sean Gouglas

Sean Gouglas (PhD) is

Director of

Interdisciplinary Studies

in the Faculty of Arts at

the University of Alberta

and an Associate

Professor in Humanities

Computing. He is also a

theme leader for

Canadas Graphics,

Animation and New

Media NCE. His research

focuses on universities

and the game industry,

as well as women in

gaming. He is amused

at the irony that his coauthor is now analyzing

metrics for a large

company.

seangouglas@gmail.com

archive

RSS

volume 12 issue 2

December 2012

ISSN:1604-7982

Search

The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as

Art

by Michael Burden, Sean Gouglas

Abstract

The videogame Portal is an algorithmic exploration of human struggle

against algorithmic processes that have superseded their original

intended purpose. The game explores the search for freedom from

such computational processes. The freedom presumed in the portal

gun - which allows access where there was none - is circumscribed by

creating pathways that only open back into the maze of the Aperture

Science Facility. The promised reward for completing the algorithm is

freedom, but the promise is made by a master chained to the very

facility it controls. Both GLaDOS and the player are bound to complete

the algorithm. There is no escape.

Portal extends this tension, perverting the traditional relationship

between player and protagonist. Each test requires inputs to

complete, with the companion cube serving as a necessary but

disposable means to that end. What the companion cube is to Chell so

Chell is to the player - she reappears after each failed test like a

weighted companion cube dropping from a chute.

Harmony between the game mechanic and the story ensures

emotional resonance between Chells suffocation in the workings of

the system and the players own frustration in moving through the

game. Unlike other artworks, Portal not only communicates emotion

but also allows for play to achieve it. Thus when the narrative pushes

Chell to complete the tests by being incinerated, the players own

yearning to escape the confines of GlaDOSs control reaches its own

breaking point, synchronizing the goals of both player and

protagonist. This aesthetic of play speaks directly to the relevance

artistic videogames hold for {INSERT AUDIENCE HERE}.

Keywords: Portal, Art, Algorithms, Testing, Videogame, Aesthetics

"We all know that art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes

us realize the truth."

Pablo Picasso: The Arts (1923)

"The cake is a lie."

Portal (Valve, 2007)

Introduction

Algorithms, the step-by-step processes that permit simple and

complex computation, provide powerful shorthands, allowing control

and exploitation with the promised certainty of reliable outputs. In

everyday life, algorithms surround us, and we increasingly give

agency to algorithms that are too complex for our understanding:

1. Algorithms control financial trades without oversight, as

humans toil on the ground serving the algorithms needs

(Slavin 2011)

2. Algorithms refine exposure to information, serving as

gatekeepers to that information, creating and reinforcing

perspectives (Pariser 2011)

3. Algorithms determine whether to receive an email or silently

trash it (Brownlee 2011)

4. Algorithms shape the development and release of books and

films (Wakefield 2011)

5. Algorithms keep aircraft in the air (mostly) (Heasley 2011)

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

1/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

Algorithms are optimized for defined inputs and repeatable processes.

However, unless the algorithm matches some fundamental law - if it

only holds to a temporary pattern in the social construct - then

eventually the reliable results of the algorithm will be invalid and

untrue (Martin 2009). Algorithms are unable to adapt to change, and

we are limited by the parameters of the machine and the way it is

designed to process those parameters.

Algorithms, however, are more than just instructions that run

software. As algorithms are used in and applied to social situations

they become forces that shape and persuade. Bureaucracy is just one

well-known example of the tyranny of ceding control to Kafkaesque

algorithmic processes. Rigid testing protocols of a quality assurance

lab would be another.

All videogame mechanics at their most fundamental level are

algorithms (Sicart 2008; Hunicke, Zubek, LeBlanc, 2004), which

Manovich (2001) sees as an explicit hallmark of videogames. The

game world is an algorithmic simulation of physical existence.

Videogames uniquely combine the qualities of game play, world

simulation and narrative (Lindley, 2003). As such, videogames provide

a fruitful medium for the exploration of what it means to be a human

in a world increasingly dominated by algorithms.

GLaDOS, an artificial intelligence that serves as the antagonist in

Portal (Valve, 2007), is a collection of complex algorithms unified in

single purpose to test for testings sake - and the algorithms have

gone mad. Chell, the test-subject protagonist, is nothing more than a

necessary algorithmic input. The experiments within the Aperture

Science test facility act like algorithms, taking their input and

producing output: pass or fail. Death for Chell is just a failed test - a

mark recorded amongst the other data for later statistical analysis in

the search for Taylorist efficiency. As GLaDOS has lost all external

context beyond her own functioning, Chells escape from the algorithm

is necessary for survival.

This paper argues that the increasingly algorithmic nature of everyday

functions and interactions creates an opportunity for self-reflexive

videogames to be especially relevant as an artistic medium it is our

embeddedness in an algorithmic world that is a natural fit for

videogame mechanics and affordances. To make this argument, we

examine four points. First, critical engagement with specific

videogames is more important to the general acceptance of the

medium as art than meta discussions about the potential of the media

to be art.

Second, through a close reading, we assert the art-worthiness of the

wildly successful videogame Portal. Given the games almost universal

acclaim, holding Portal up as art may seem like plucking low-lying

fruit. However, extended critical discourse of the game is lacking

most game pundits and theorists instinctively acknowledge its artworthiness without dissecting in detail its artistic integration of

mechanic, narrative and theme. The key mechanic1 - a gun that

shoots portals or tunnels that allow physical movement between

unconnected spaces - explores the meaning of freedom when trapped

in the algorithmic processes of what we perceive as reality.

Third, we argue that Portal explores what it means to be within a

game and to escape from that game an ironic function as Chell can

never leave the game and the player cannot escape until he or she

has completed the tasks laid before them by the designers. The

restrictions of space and agency become the mechanism of the

games functioning, subverting most of the genres well established

tropes: the training level becomes the game; the princess rescues

herself from the castle; the player dances behind the curtain as well

as on stage. The central narrative is the main characters search for

answers and escape while serving as the experimental subject of an

algorithmic machine focused on testing purely for testings sake. The

games chief conceit rests on the computer gone awry, presaging the

algorithmic control and growing dominance of metrics, analytics and

surveillance in modern society. Portal explores these issues by

subverting the proceduralist, quality control mechanism by which

production and truth are obtained. Identity and subjection are mixed

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

2/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

as an increasingly hostile and ever more perverted Milgram

experiment is inverted and repeated.

And finally, we examine the tension between the confines of a game

(its rules, controls, levels) and the expressive freedom of art to

challenge rules. Play engages the audience in different and potentially

complementary ways as compared to the intellectual and emotional

engagement of art. Through play, the game provides an artistic

comment on both the human condition and the medium.

The Art of Videogames

The debate over videogames as art has been contentious, although

the discussion seems to have diminished in the last year or so. Most in

the gaming community seem convinced that games can be art, and

there seems less opposition elsewhere, although perhaps still no clear

consensus. Still, the matter continues to hold interest (Muzyka and

Zeschuk, 2011), as does the debate as to whether any authority can

bestow the label 'art' on a medium. Some see such a blessing in the

National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) announcement that it will fund

videogames as art (Bogost, 2011), the Smithsonian American Art

Museum's 2012 exhibit on 'The Art of Video Games,' (Smithsonian,

2012), or Roger Eberts exasperated concession Fine - Go play with

your toys (Stuart 2011)2.

Although perhaps too narrow an assertion, there appear two

motivations for considering videogames as art. The first, which seems

to be driving the public debate, is a search for legitimacy or relevance

for a popular medium. This motivation has trickled into the academic

discourse as some seek to convince their somewhat skeptical

colleagues and administrators of the intellectual authenticity of their

object of study. This debate, we believe, will lessen and ultimately will

be settled by inertia as the critical discourse around and about games

becomes increasingly enmeshed within the mechanics of academic

legitimacy: grants, publications and curriculum.3 In time, an imagined

sufficient quantity of anointed artistic games will reach the

consciousness of enough people that widespread acceptance will be

gained.

There is persuasive evidence that such a quantity has already been

met, with developers exploiting the affordances of videogames to

construct art or embed an artistic message. For example, Daniel

Benmerguis Storyteller (2008) seems an intentional artgame with the

interactive nature an essential element. A commercial game with

artistic merit such as Portal is different. It is produced with profit in

mind, despite the artistic freedom allowed its creators.4 Such

videogames employ the procedural rhetoric within games to expose

their world to the exploration of the audience (Bogost, 2007). A

growing critical mass of games exploring such issues present the case

for games as art simply through their excellence: Ico (Team Ico,

2001); Flow (Thatgamecompany, 2006); The Marriage (Humble,

2007); Passage (Rohrer, 2007); Flower (Thatgamecompany, 2009);

Braid (Number None, Inc., 2008); Graveyard (Tale of Tales, 2008);

Everyday the Same Dream (Molleindustria, 2009); Limbo (Playdead,

2010); and Journey (Thatgamecompany, 2012). Like film before it,

games are or will be viewed as art and therefore a legitimate object of

study within a broader university community simply because standing

against this tide will be too difficult.

The second reason, which is more problematic and therefore more

interesting, builds on and lends weight to the first. In participating in

the debate on whether games are art, game theorists and critics gain

access to both a forum for discussion and a critical intellectual

apparatus in the examination and study of games. The debate itself

creates a discursive headspace for game study. Other forms have

made this journey before: film, graphic novels, pornography, etc.

(Carroll, 1998). Each has travelled the road in a slightly different

manner, negotiating and altering as appropriate to the mediums

affordances the various critical tools needed for effective engagement.

However, if calling a videogame art opens up these critical

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

3/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

opportunities, so too would calling it a text or a cultural object. Each

label unleashes a host of interpretive tools that could be adapted to

the peculiarities of the medium, with a semiotic deconstruction or

cultural studies encoding/ decoding providing as reasonable a first

step as the assessment methods of art historians. And yet, this

process was already well in hand without resorting to art criticism.

Aarseth (2003), Gee (2005), Consalvo and Dutton (2006) and Bogost

(2007, 2008) have already provided such paradigms, creating spaces

and toolboxes for effective engagement with the medium, as have

Konzack (2002), Malliet (2007) and Myr (2008). Perhaps in a few

years, critical assessments of videogames may depend exclusively on

these efforts, and will not require at least some comment on the

medium as art. We are not there yet.

The core challenge in defining art-worthiness, identified by Weitz

(1956), is that any definition presupposes a limit on what new art can

entail, which will inevitably be challenged because that is a function of

art itself. Robert Sharpe, for example, asserts that difficult boundary

cases of art remain fairly intractable, and for this reason he suggests

that Berys Gauts cluster concept is perhaps best equipped to deal

with the idiosyncrasies of the concept (Sharpe, 2001, p.275). "Gaut

provided 10 points to evaluate an object as art, including possessing

positive aesthetic properties, being expressive of emotion, and being

intellectually challenging"(Gaut, 2000). A group of artifacts might

qualify as art without satisfying all ten points.

Another response is that acceptance of art is often institutional, where

art is art in light of things already adjudged as art (Carroll, 1998, p.

7). This acceptance of art into the art world as a key factor in

determining art appears in other critical works. Eaton (1983) suggests

that communities decide art, while Bailey notes the need for some

community to consent to an objects status as art (Bailey 2000).

Mandelbaum (1956), drawing on Wittgensteins discussion of game

and family resemblance, offers a useful analogy. New artifacts require

at least some genetic legacy to earlier generations of critical

discourse. The legitimization of film as an art form could serve as such

a touchstone for the legitimization of videogames. Henry Jenkins, for

example, finds such inspiration in a paper revisiting Seldes' The Seven

Lively Arts, finding significant parallels for videogames (Jenkins 2005).

For this reason, Shyon Baumann's analysis of the process by which

Hollywood film became legitimized as an art form is highly

constructive. Baumann identifies three major aspects: societal

changes created an art space for film to develop, Hollywood changed

bringing it closer to well-established art communities, and critics

emerged engaging in significant and extended critical discourse about

film (Baumann, 2007, p. 3).

There have been important approaches from within the philosophy of

art community to consider the art-worthiness of games. Smuts

(2005), for instance, considers the viability of videogames against the

major theories of art: having a manifest aesthetic, acceptance on

institutional grounds, aesthetic evaluation and the role of auteurs.

Smuts argues that each of these definitions can be satisfied by

videogames, of which a few candidates exist although general

consensus of masterpieces is still lacking. Tavinor (2009a) found

Smuts' individual arguments less than watertight but agreed in

principle that videogames could satisfy any definition of art. Correctly,

Tavinor identifies as a chief challenge the interactivity of games

(2009b). This is a useful caution as interactivity is the defining nature

of videogames much like pointing out that painting could be art if

only one could get past all the brushstrokes. Interactivity provides a

potentially unique opportunity for commenting on social and cultural

issues. Presaging Bogosts idea of procedural rhetoric, Zimmerman

asserts,

It is clear that games can signify in ways that other

narrative forms have already established: through

sound and image, material and text, representations of

movement and space. But perhaps there are ways that

only games can signify, drawing on their unique status

as explicitly interactive narrative systems of formal play

(Zimmerman, 2004, p. 162).

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

4/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

Such a function is the mediums strength. By focusing on Gaut's

cluster theory, Tavinor shows how various videogames (including

Portal) can be used to satisfy each of the 10 required criteria (2009a).

In a follow up article (Tavinor, 2010), he argues the case for all of the

criteria using Bioshock as an extended example.

What can be taken from both Gauts and Baumann respective third

points is the need for engagement with the medium, including

exhibition, award and critical analysis. The quality and thematic

complexity of some modern videogames invites such critical

discourse: Braid explores issues of time and regret in a love affair;

Flow explores consumption, evolution and death; The Marriage

explores the fragility of relationships over time when balanced with

the personal needs of the partners; Limbo explores our deepest

psychological fears of death and longing; Ico juxtaposes the playful

adventures of a young boy against a young womans keen awareness

of their real danger.

Here, we critically engage with the game Portal, demonstrating that it

explores a multitude of themes about human existence and modern

life in intelligent and unique ways. This analysis does not explicitly use

the paradigm of either Gaut or Baumann as the scaffolding upon

which to assert its case that videogames can be art. Instead, this

paper provides a critical engagement with one videogame, which is

essential to both Gaut and Baumann. This paper (one among a

growing number of papers) takes up the challenge of the 2010 Art

History of Games conference, which asked the question: What about

videogames is artistic?

Rage against the Machine

The Game

Portal, written by Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek, is a single-player,

puzzle-solving, first-person shooter released by Valve in 2007 to

critical acclaim and commercial success, with total sales in excess of

four million copies (Magrino, 2011).5 The player controls a female

human named Chell, who awakens to a bright overhead light in a

spartan glass cage. Movement is free but restricted - there is no

obvious escape as there is no door, only a pod-like bed, toilet, radio,

video screen, mug and clipboard. An unseen synthesized voice begins,

Hello and again welcome to the Aperture Science Computer-Aided

Enrichment Center. We hope your brief detention in the relaxation

vault has been a pleasant one. Your specimen has been processed and

we are now ready to begin the test proper (Portal, Test Chamber

00).6 The lack of shared memory between the player and Chell

dovetails with the cognitive impairment of prisoner isolation (Travis &

Waul, 2003). The only focus, for both, is as test operant.

The primary game mechanic - and purported purpose for the tests - is

the portal gun (the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device or

ASHPD), which allows shooting separate sides (portals) of a spatial

connection into different locations. Thus shooting one portal at a wall

next to the player and the other, paired portal at a wall far away

allows the player to move between the two portals as though they

were two sides of an open doorway. Some might find the term

wormhole helpful. The portal gun, obtained in Test Chamber 02 but

not made fully functional until Test Chamber 11, is required to

complete the tests. This necessary instrument ultimately provides the

means for Chells escape.

The story of Portal is initially told through exposition and experience.

The player is within a contained environment (not unlike being a test

lab rat) and is presented with challenges that move the player into the

next confined space. While this reality is evident through experience,

exposition occurs in the form of a computerized voice in the tannoy

speaker system, eventually revealed as GLaDOS, which presents itself

as both the operator of the tests and, at least initially, the benevolent

female guide representing the Aperture Science research team.7

During the initial levels, the voice betrays a personality that is slightly

unhinged, blindly following some perverse test protocol: Please be

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

5/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

advised that a noticeable taste of blood is not part of any test

protocol, but is an unintended side effect of the Aperture Science

Material Emancipation Grille, which may, in semi-rare cases,

emancipate dental fillings, crowns, tooth enamel and teeth. (Test

Chamber 02)

Although the modulated voice and garbled syntax of GLaDOSs

introductory speech suggests that she is not quite human, the player

cannot be entirely sure the voice is a computer until Test Chamber 06

when null values in the database become manifest. GLaDOS praises

Chell for successfully navigating a difficult test chamber:

Unbelievable! You, {SUBJECT NAME HERE}, must be the pride of

{SUBJECT HOMETOWN HERE}.

Unlike the Wizard of Oz, or the Mechanical Turk before it, this quick

peek behind the curtain reveals not the person behind the machine,

but the machine behind the person. Tellingly, GLaDOS seems unaware

of her verbal mistake and how Chell might perceive these uninitialized

parameter errors. The algorithmic space created by GLaDOSs

programming is optimized and coded for testing and it runs

relentlessly regardless of consequence. She not only ignores the

interpretive consequences of her mistake, she seems completely

oblivious to them. The testing algorithms are always geared towards

reliability, even at the expense of sense (in logic terms, they are valid

but not sound). As the game progresses, the benevolent voice

masking GLaDOSs murderous intent cracks, then shatters.

A parallel dissonance colours the players relationship with Chell. The

first person perspective and the agency provided by such interactions

create a sense of connection between the player and the avatar in the

gameworld - she is more than an empty shell. Some players may

even assume that they are Chell - akin to Heideggers notion of a tool

being ready to hand rather than present at hand (1962, 1, III, 15). It

is possible for the immersion to be sufficient that players never realize

that Chell is an intermediary between the games actor and

themselves.8 Chells lack of backstory and her silence throughout the

game fosters this identification.

However, through a fairly simple arrangement of portals, the player

can glimpse Chells physical appearance. Obtaining these partial

views, in fact, becomes a game in itself, as the player seeks to espy

more complete views of the protagonist, never quite constructing a

complete image. This wonderfully Lacanian captivation with the self

obtained through mirror-like portals plants a troubling seed: you may

control Chell, but you are not Chell.9

Test Chamber 17

Each test chamber becomes more difficult, introducing increasingly

complex consequences made possible by the affordances of the portal

gun, while GLaDOSs prompts to complete these tests become more

insistent. Obedience to authority, particularly scientific-institutional

authority, permeates all aspects of Portal with the game serving as an

instantiation of the Milgram experiment an infamous experiment

that examines the willingness to obey an authoritative voice cloaked

in the mantle of science (Milgram, 1963). GLaDOS compels the player

to be part of the algorithmic process.

The player is placed in the dual role of the learner who suffers for

failing to complete increasingly more difficult test chambers, and the

teacher who punishes his or her recalcitrant student. Wearing the

cloak of the Learner, the player as Chell is at first enticed, then

goaded, then guilted and finally threatened to complete each test.

Constantly punished for each failure (usually with death) and

increasingly demeaned when successful.

As Milgrams Teacher, the player pushes the buttons that prod Chell to

complete each task, punishing her with each failure. These concurrent

roles crystallize the players identification with and separation from

Chell. GLaDOS serves the role of Milgram, prompting the teacher to

inflict greater and greater acts of barbarity: longer jumps, riskier falls,

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

6/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

fatal electrocutions.

In Test Chamber 17, the obedience to authority experiment is laid

bare, where both Chell and the player are urged, for the good of

science, to incinerate an inanimate companion cube in an Aperture

Science Emergency Intelligence Incinerator. GLaDOS positions the

faithful companion cube, a large, heavy cube covered in pink hearts

that is needed to hold down buttons to open doors in some tests, as a

friend to Chell - a friend that needs to be destroyed to make further

progress in the experiment/ game possible. Chell and the player may

reasonably hesitate to incinerate the cube given its personification and

the fact that the fiery pit is called an Intelligence Incinerator. Such

hesitation leads to increasingly insistent promptings from GLaDOS,

the Milgram scientist, pressuring the player to conform to the required

process. GLaDOS insists (Test Chamber 17),

"Rest assured that an independent panel of ethicists has absolved the

Enrichment Center, Aperture Science employees and all test subjects

for all moral responsibility for the companion cube euthanizing

process."

"Testing cannot continue until your companion cube has been

incinerated."

"Although the euthanizing process is remarkably painful, 8 out of 10

Aperture Science engineers believe that the companion cube is most

likely incapable of feeling much pain."

"The companion cube cannot continue through the testing. State and

local statutory regulations prohibit it from simply remaining here,

alone and companionless. You must euthanize it."

"Destroy your companion cube or the testing cannot continue."

"Place your companion cube in the incinerator."

"Incinerate your companion cube."

When Chell and the player finally burn the cube, as they must to

advance the experiment, GLaDOS informs them that she euthanized

her faithful companion cube more quickly than any test subject on

record. Congratulations." Even here, when the Milgram-like nature of

the experiment is clear, GLaDOS continues her testing, providing a

Taylor-like efficiency assessment of the players willingness to inflict

pain on the Learner.10

This scene serves two additional purposes. First, it trains the player in

steps necessary to complete the game in the final confrontation. As

mentioned earlier, Portal inverts many gaming conventions. In this

case, the tutorial level is, in fact, the game. Second, it foreshadows

Chells fate. As Chell treats the companion cube, GLaDOS treats

Chell.

You are. The companion cube...

The last four test levels contain barely-hidden niches that lie outside

the extant test environment. In these it is evident that at least one

other person has navigated the test facility in resistance to the

system. These dens contain scrawls and drawings that provide

encouragement and warnings to Chell as she navigates the facility.

Later identified as the stenographic ramblings of Doug Rattmann in a

comic called Portal 2: Lab Rat, the scribbles depict the troubled mind

of a former Aperture Science employee trying to assist the

protagonist, a mind that is all too aware of GLaDOSs constant

surveillance and malevolent intent.

Clearly, Rattmann is insane, a state of mind that arose from his

conflict with GLaDOS, but his insanity now protects him as he

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

7/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

navigates the realm behind the curtain. Like John Murdochs

awareness of the experimental machinery of the lived space of Dark

City (1998), Rattmanns knowledge of the inner-workings of the

machine is to be considered insane by any reasonable measure - both

the cake and Shell Beach are lies of the system.

One scribbling, arranged in a concentric circle around photographs of

a family of personified companion cubes at the beginning of Test

Chamber 17, states the following: I'm not hallucinating. You are. The

companion cube would never desert me. Dessert. So long... Cake.

Haha. Cake. A lie. The companion cube would never lie to me. Hidden

from GLaDOSs gaze within these seemingly mentally unstable

ramblings concerning the ultimate reward of cake, is the concealed

yet ominous warning You are. The companion cube. The assertion is

more than simple foreshadowing of Chells incandescent death at the

hands of GLaDOS, it is Rattmans warning to Chell that she has

another companion in these tests in addition to the cube.

On the face of it, Chell serves the role of Milgrams Teacher,

tormenting and ultimately incinerating her silent companion cube at

the promptings of GLaDOS for the benefits of science. However, Chell

also serves as the silent companion to the player, who with reckless

abandon allows Chell to die multiple times en route to the games

completion, always confident that a new Chell will appear, like a

weighted cube dropping through the chute. Rattmanns scribbles,

therefore, warn Chell to beware the player. The game is a lie.

In this light, GLaDOSs cautions to ignore conversation with the

normally silent companion cube take on an even more sinister tone.

GLaDOS, who may have tested hundreds or even thousands of

humans, may understand the affect that isolation and hopelessness

have on the human psyche, and therefore deemed it necessary to

warn Chell of an unhealthy attachment to the cube. However, if

Rattmanns warnings are to Chell, then GLaDOSs warnings are to the

player: ignore your silent human companion should she object to what

is necessary to complete the test protocol - let her burn.

Test Chamber 19

In addition to the burning of the companion cube in Test Chamber 17,

other events foreshadow Chells fate: for example, in Chamber 13

GLaDOS states, When the testing is over, you will be ... missed; and

in Chamber 16 a message intended for a robotic test subject is

delivered to Chell, "Well done, android. The Enrichment Center once

again reminds you that Android Hell is a real place where you will be

sent at the first sign of defiance."

As Test Chamber 19s obstacles are completed, Chell is on a moving

platform in an enclosed tunnel. A sign indicates that Cake - which

was promised for successfully completing all tests - is around the

corner. Instead, the platform is headed directly toward a burning pit.

GLaDOSs homicidal intent and indifference to suffering becomes

remarkably clear. The cake is a lie and the reward for successfully

navigating the tests is death. The test subjects purpose is to produce

data; consideration beyond this is immaterial. Chell has fulfilled her

purpose as a test subject and, like the cube, is now expendable, ready

to be replaced by the next test subject. In Gramscian doublespeak,

where the subordinate class comes to view the oppression as natural

and expected, GLaDOS congratulates Chell on the successful testing

and imminent death:

Congratulations. The test is now over. All Aperture

technologies remain safely operational up to 4000

degrees Kelvin. Rest assured that there is absolutely no

chance of a dangerous equipment malfunction prior to

your victory candescence. Thank you for participating in

this Aperture Science computer aided enrichment

activity. Goodbye. (Test Chamber 19)

Science was advanced, with nothing of value damaged in the process.

This murderous intent brings together multiple narrative elements

foreshadowed in the game, but also emphasizes the appropriateness

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

8/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

of the game mechanic for advancing that narrative ludonarrative

harmony (Hocking, 2007). Portals can only be affixed to visible

concrete walls. So far this has resulted in the cruel irony of a device

that can connect any space only permitting connection back into the

chambers that are Chells prison. At this key point in the game, about

two-thirds of the way through, the player might simply watch as Chell

moves helplessly to her fate. No icon or suggestion indicates that the

gameworld is offering anything more than this perverse, Kafkaesque

fulfillment of the testing protocol.11 There is no guarantee that the

player will notice in time a distant concrete wall behind and above the

fire pit. It is up to the player to fight for survival against the system

and recognize that the portal gun which seems shackled to Chells

arm - is in fact her means of escape. Although, ironically, the path of

escape and its reward trade the Test Chambers of GLaDOS for the

ongoing level restrictions of the game designers the player and Chell

remain slaves to the games story.

Unlike a film, a videogame can create a story that requires the player

to act, to instantiate Chells desire to stay alive. The gun stops merely

opening portals into other test chambers. The player takes the

initiative without knowing what the goal is. Self-reflexively, the game

cedes narrative control to the player, demonstrating the power of the

videogame medium, which Ebert indicated as a fundamental flaw of

story in videogames. It is, in fact, its narrative strength.

Escape

With her escape from the fire, the testing protocol is shattered. The

player collapses GLaDOSs Milgram paradigm, re-merging with the

protagonist in common purpose to escape the facility (but not the

game). This disturbance to the algorithm also reveals the final piece of

the GLaDOS story. At the moment of Chells escape, GLaDOS drops

any pretense of representing a team of scientists working for Aperture

Science. She uses the pronoun I for the first time to describe her

intent.12 The story is now clearly the struggle of woman against

machine.

Chell and the player then move through the infrastructure of the

Aperture Science facility, which to this point has only been revealed

through slips in GLaDOSs speech or the tiny chinks in the armour that

are Rattmanns dens. In Campbellian terms, Chell crosses the

threshold to see the dark, institutional inner workings in its entirety.

The portal gun opens a wormhole that deconstructs the facility and

shows visually, experientially and narratively, the belly of the beast.13

In the final showdown Chell confronts GLaDOS, who appears

enslaved, bound by tubes and wires to the very structure of the test

facility. The machine has escaped the control of her scientist creators

but has not found freedom. Instead, in Hegelian fashion, the master is

enslaved in her role as a master. She is imprisoned, perhaps even

more than Chell, as algorithmic constraints parallel her physical

imprisonment. In computational theory, the Halting problem means

that GLaDOS cannot know if she or any algorithm she sets in motion

will ever finish. To find out, she must test. This could be taken further.

For example, the Robertson-Seymour Theorem shows that the proofs

to many classes of problems are non-constructive. This means that

algorithms to solve such problems exist, but we can never know what

they are. One would imagine such a contradiction would force GLaDOS

to test. Relentlessly. In Portal 2, much simpler paradoxes play a key

role in advancing the plot.14

The boss battle is technically straightforward, in part because of the

training the player received in Test Chamber 17. GLaDOS is destroyed

by fire in a convenient Aperture-Science-Emergency-IntelligenceIncinerator, echoing Chells near-death experience. Psychologically,

the battle is more difficult. Shackled to the walls, GLaDOS appears a

tormented figure. It does not help that GLaDOS tries to reason with

Chell during the process, saying, "This isn't brave. It's murder.".

Although necessary to complete the game, there seems reason to not

kill the tormentor (Towell 2008). The experiment, however, must be

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

9/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

completed. GLaDOS releases a nerve toxin that will soon result in

Chells death, once again prompting, goading and ultimately forcing

the player to finish the test and win the game.15 Chell, the player and

GLaDOS are all seemingly free.

This ending shows that Portal is a winnable game. The winnability of

videogames is considered a reason, for example by Ebert (2010), to

consider them as sport rather than art.16 But, Portal does not keep

score; instead its integration of narrative and game mechanic drives

the play toward completion (Woods, 2007). On the spectrum between

competition and puzzle, Portal leans closer to the latter, separate from

competition-intense videogames (Aarseth, 2004).

Being a puzzle, Portal does gain its art-worthiness in a matter like

films: a specific objection might be that it has a linear plot. However,

in addition to the agency of the player in enabling that plot to take full

form (i.e., the players saving actions before the fire), the experience

of the plot by the player is uniquely suited to the interaction that is

only possible in a videogame. Leigh Alexander explains,

Even the simplest game is a series of mechanical

choices. Thats why players and designers are so

obsessed with the concept of choice in games; make

choice meaningful, make them affect what happens in

the gameworld. Just adding the element of interactivity

can make those narratives so much more complex and

powerful because you feel responsible for it (PBS

2011).

Portal takes the ability to make the player feel responsible for the

experience of Chell within the test regime of the facility, and pushes it

to extremes as, just like in the Milgram experiment, the test subject is

guided to the point of committing murder.

Gaming Tropes

GLaDOS and Game Design

The agon of Portal is the challenge of each test chambers puzzle, but

GLaDOS is the source of that conflict. She created the environment

and challenges that Chell must complete, much like videogame

designers do for players. And like GLaDOS, designers remain (mostly)

unseen, experienced through the challenges and environments they

create.17 The game designers, GLaDOS, Chell and the player are

known through that creation. All are trapped in it.

Chell and the player wander the path laid out for them by their

respective designers, seeking the source of their imprisonment. Upon

finishing the game and revealing the designers schemes, both are

free to be in the world, having ended their trial. Chell destroys the

research facility and kills her master, awakening in the middle of a

parking lot surrounded by debris, sunshine, clouds and apparent

escape. Interestingly, shortly before the sequel was released the

original games ending was reversed so that Chell was not free but

dragged back into the system, an idea that had been proposed as the

original ending (Reeves, 2010). That ending adds more horror to

GLaDOSs first words, Hello and again.18

For the player, this openness is the end of the game and its control

over the player. There is, however, an end-title sequence

accompanying the credits in which a song provides a more

sympathetic view of the controlling GLaDOS character. The song is

perhaps a vindication of the game creators for their role, or just a

reminder that all is in jest in a game. Either way, the player may then

move on to whatever else needs to be done or play again, like a good

test subject.

The Game Mechanic

One of the beautiful aspects of Portal is that design and play of the

game fully realizes and then transcends many of the core notions and

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

10/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

tropes of videogames. The association between GLaDOS, game

designers and dungeon masters are not the only form of this.19 The

test chambers embrace the limitations of level design, restricting the

area in which the contest occurs, like Huizingas sacred circle

(Huizinga, 1955). A game level must be designed, often in the way

that a theatre set represents reality: by backdrops, false barriers and

other tricks. In Portal the limitations of level design are embraced: the

Test Chamber is unequivocally the extent of the level, without false

walls or landscape backdrops (although in the second half of the game

there are blocked doors).20 The only existence is the level and the

concurrent tension between Chells desire to escape and the players

desire to finish.

The agency of the player - their capacity to act - is extended through

possession of the portal gun, which allows space to be overcome and

the player to create their own spatial connections. But this comes with

heavy limits: it can only shoot onto surfaces that are already extant,

and only a particular type of surface that seems to reside only in the

test chamber - the promise of freedom does not lead to freedom

beyond the control of the game designer (GLaDOS). In Portal, the

guns apparent freedom always opens up into the same trap.

The game mechanic concerns being within the confines of the

constructed space. Ultimately, though, the player is able to move

beyond the testing environment, called the "Enrichment Centre," and

into the freedom of the facility behind. This backstage does not

replicate an entire virtual facility, only the space required to guide

Chell through the puzzles that lead to GLaDOS. As Chells life as a test

subject breaks down so does the completeness of the game designers

levels. The entire illusion shatters as both Chell and the player see the

scaffolding of the facade.

The question of a level without a game can be considered. A common

cheat in games is no clipping (the players avatar is not stopped by

walls in the virtual world and becomes as a ghost). This is to go

beyond the game designers construct to truly explore with freedom.

The portal gun embodies this idea, but the player cannot leave the

confines of constructed space. If you enable this cheat in Portal, you

can get anywhere, but what do you do in a space such as the cake

room without the game being present? Other games explore this

tension. For example, this idea is inverted in The Path (Tale of Tales,

2009) where the game only becomes a game when the player breaks

the only rule of the game: stay on the path.

A videogames exploration of procedure can also include natural

processes. In Braid, the game mechanic allows the flow of time to

disengage from the physical and draw closer to the psychological

experience of time; another medium might represent time like clocks

melting in the sun. Because time is a dominant process in human

experience, it is not surprising that the experience of the passage of

life over time is a frequent theme of artgames. The agency of the

player is crucial to accessing this experience.

The Algorithmic Experience

A reasonable direction to pursue in closing this paper would be to

return to the videogames-as-art question, running through Gaut's

checklist of ten points to see if Portal is, in fact, art. But this paper's

purpose is not about keeping score but to discuss the artistic elements

of Portal, contributing to the growing community of scholars engaging

critically with the medium. Portal's art-worthiness is in its exploration

of the increasingly algorithmic nature of the world.

Art, however, is an exploration of human thought and creativity - an

act of freedom. Algorithms, those cold, dry entities of the computer

age, are foreign to it, despite the beauty they may create. They

appear predictable, repetitious, automatic. Such qualities could be

considered strengths when applied to systems requiring efficiency,

repetition and redundancy - useful when people are considered as

abstract entities needing regulation and control. Here lies the tension

between our moral sense and the pressure to conform to authorities

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

11/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

demanding the incineration of an unnecessary apparatus. The ability

of algorithms to perform sufficiently better in the regulation of human

affairs leaves us without the confidence of our own identity - those

who can see beyond the system's assumptions can only scrawl the

truth on the confined walls outside the official chamber.

Portal presents these tensions to us. It is the tension between the

cold, hard certainty of algorithms and the creativity and freedom of an

art. It is the tension between the algorithms simplification of complex

concepts versus the need for problematization and criticism. It is the

tension between a world without questions and the inquiry that art

embodies. It is the tension between knowledge that emerges from the

algorithms of the scientific method and the human knowledge

encountered in art. All videogames are algorithms, and therefore,

Portal is an algorithmic exploration of human struggle against

algorithmic processes. The games very nature is an adherence to

rules. Arts very nature is to challenge rules, to the point of defying

definition.21

This leads to a curious challenge for videogames as art: the algorithm

must be obeyed. Perhaps most significantly, the game requires inputs

from a game controller, which are mapped to permitted avatar

actions. There is no game unless the player is tied to the controller.

Juul (2010, p.133) has shown the futility of resisting this demand

while playing (or technically, not playing) games like The Sims (Maxis,

2000) and Scramble (Konami, 1981). In Portal, if the player never

picks up the controller the game stays in the opening chamber, Chell

never leaves the Relaxation Vault; the game camera stays fixed on a

view of an open portal while the radio loops the same song. There is

nothing more.

Such controllers may be familiar to a generation raised on FPS games,

but they may be unwieldy to the uninitiated. Even if the audience/

player picks up and understands the controller, they still have to

demonstrate a certain facility to progress through the game. They

need to make portals hit their targets. They need to complete jumps,

sometimes against a clock. The games mechanism requires a

particular form of competence in the player. This takes training,

practice and learning. It is like demanding that the audience first learn

to ride a unicycle before they can see the play. This is not

performance as art, but action as necessary in order to have the

experience. But, it is still a barrier.22

Play is free activity but Portal only offers this in constrained doses.

Failure to play as the game requires will result in a failure to

experience the game at all. To participate in the algorithmic aesthetic,

one is required to act constantly and competently. This is a cruel

restriction - to showcase something defiant to display.23 Although the

output of the game is experienced visually and audibly, recording and

displaying a play-through of the game to be displayed like a film

would miss the point entirely.

It robs the experience of all those elements described throughout the

paper: the discovery that the tools for performance of the tests

permits escape, but an escape still bound to the test chambers (at

least until the final test); the dread felt as passage through the test

chambers unfolds a story as suffocating as the player's inability to

escape from the testing. These elements go beyond the aesthetic of

the game's output - beyond the aesthetic of its images, its sounds, or

the aesthetics of its story. This is the aesthetic of play.

The demand for competent input from the player is a barrier, but a

necessary one to emphasize a vital strength of the medium. The plain

fact [is] that it takes a player to play a game. (Koster, 2012). Games

demand physical engagement, but in asking more, more is offered.

Games may put up a barrier by forcing the player to pick up the

controller and jump through a few hoops in order to experience the

art object. But this is only so that control can be given to them, in

order to engage the audience directly: to reveal the world of the

artists imagination. Not to a passive, though intellectually engaged,

audience but to an audience that is engaged in play too.

To date most games have missed the opportunity to enhance their

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

12/18

9/4/2015

Game Studies - The Algorithmic Experience: Portal as Art

intellectual engagement in ways that are only possible as playful

engagement occurs. Portal is not one of these. The experience of the

algorithm Chells experience resonates because it is the players

experience too. Chells subjugation to process, her desire to act freely,

her hopelessness as she incinerates a silent friend these are not

transmitted to the player through the artistic medium but belong to

the player as their own.

Exploring the machine gone mad is hardly a new idea in science

fiction.24 However, the procedural nature of games provides a unique

opportunity to explore the increasingly procedural nature of such

increasingly prevalent technology. Interaction is essential to this

exploration. Trapped within the Aperture Science facility, subjected to

algorithmic constraints that frame all knowledge production as

process, Portal artfully explores issues well beyond the confines of its

test chambers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their colleagues and three anonymous

reviewers for their assistance in drafting this paper.

Endnotes

1

Josh Weier, project lead for Portal 2, reflected on the importance of

the portal gun to the story by stating, I have my portal gun, and

everything is dripping from that (Francis 2010).

2

Interpretation - not a direct quotation.

To see a summary of such efforts in Canada, see Gouglas et al,

2010.

4

We might use the word auteurs with respect to Walpaw and

Faliszek, although the appropriateness of this label remains debatable

as it applies to interpreting games coming from AAA studios. See, for

example, Dermibas (2008).

5

It is not clear whether these sales were just the stand-alone version

of Portal, or whether they included sales of The Orange Box a

collection of games that included Portal.

6

Although Valve would later provide more backstory to the character,

in the game itself it remains unclear how long Chell has been in the

facility or, for that matter, if this is her first time being subjected to

such tests.

7

GLaDOS stands for Genetic Lifeform and Disk Operating System and

is a homophone of Gladys.

8

As discovered by a third of the students who played Portal as part of

Wabash College curriculum (Klepek 2011).

9

This echoes aspects of Gees tripartite play on identities, where the

players action are active and reflexive of the character in the game players actions and choices not only move the character but alter the

possible future options presented to the character down the road

(Gee, 2007). In addition, with no other human characters in the

game, Portal skirts the uncanny valley problem that can hold

videogames back from conveying realistic emotions in the characters,

a limitation not traditionally faced in film.

10

The games designers have noted that the companion cube was

originally designed as a simple box (required to be carried to the end

as an additional challenge to the player), but that players often forgot

to bring the box. Erik Wolpaw, one of the games writers, learned from

government documents that isolation leads subjects to become

attached to inanimate objects (Edge 2008). Valve sells a stuffed

version of the companion cube, which is the most popular element of

http://gamestudies.org/1202/articles/the_algorithmic_experience

13/18

You might also like

- Game Studies - Playing and Gaming - Reflections and ClassificationsDocument9 pagesGame Studies - Playing and Gaming - Reflections and ClassificationsRishabh BaroniaNo ratings yet

- The Docker and Container EcosystemDocument131 pagesThe Docker and Container EcosystemMichael RiveraNo ratings yet

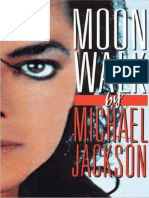

- m00nwlk Jacks0nMDocument205 pagesm00nwlk Jacks0nMRishabh BaroniaNo ratings yet

- Siv Poorana Vol1Document496 pagesSiv Poorana Vol1pallakuNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Meetings & Facilities Guide: Gaylord Opryland Resort & Convention CenterDocument19 pagesMeetings & Facilities Guide: Gaylord Opryland Resort & Convention CenterScott HerrickNo ratings yet

- Starter Activity: - Recap Previous Lesson and Discussion About The Homework TaskDocument7 pagesStarter Activity: - Recap Previous Lesson and Discussion About The Homework TaskMary Lin100% (1)

- Free Football Predictions and Soccer Tips For Games Today 2Document1 pageFree Football Predictions and Soccer Tips For Games Today 2JOHN CHRISTOPHERNo ratings yet

- Centaur or Fop - How Horsemanship Made The Englishman A Man - Aeon IdeasDocument1 pageCentaur or Fop - How Horsemanship Made The Englishman A Man - Aeon IdeasKhandurasNo ratings yet

- INSCRIPCIÓN DE ACTIVIDADES A SEMANA HSEQ-RSE 2019 (Respuestas)Document33 pagesINSCRIPCIÓN DE ACTIVIDADES A SEMANA HSEQ-RSE 2019 (Respuestas)Cristina AgudeloNo ratings yet

- Salvador Jesus Juarez Achique 10°3Document6 pagesSalvador Jesus Juarez Achique 10°3フアレス サルバドールNo ratings yet

- Homemade Fruit Kvass - Fermented Fruit Probiotic Drink - Cotter CrunchDocument2 pagesHomemade Fruit Kvass - Fermented Fruit Probiotic Drink - Cotter CrunchNemanja MartinovićNo ratings yet

- ANTONYMSDocument22 pagesANTONYMSCarla Ann ChuaNo ratings yet

- Frame by Frame RubricDocument1 pageFrame by Frame Rubricmark.lindseyNo ratings yet

- PPC 113 Lesson 1 Philippine Popular CultureDocument20 pagesPPC 113 Lesson 1 Philippine Popular CultureJericho CabelloNo ratings yet

- Emu LogDocument5 pagesEmu LogJosé BedoyaNo ratings yet

- AMIGA - Donkey Kong InstructionsDocument2 pagesAMIGA - Donkey Kong InstructionsjajagaborNo ratings yet

- SimulatorTiketi 19.3.2022Document6 pagesSimulatorTiketi 19.3.2022Djordje StankovicNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Essays LinkDocument2 pagesSanskrit Essays LinkShabari MaratheNo ratings yet

- Unit 12Document5 pagesUnit 12Freddy Miguel Ospino ospinoNo ratings yet

- Fashion Show Rubric: Clothing Articles Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4Document2 pagesFashion Show Rubric: Clothing Articles Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4BALQIS NURAZIZAHNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Chart of Basic Skating Skills: Skating Edges Skill LevelsDocument6 pagesDescriptive Chart of Basic Skating Skills: Skating Edges Skill LevelsJ9 Yu100% (1)

- ANT238 Exam 8Document2 pagesANT238 Exam 8Tanto KristantoNo ratings yet

- E Ticket 2Document1 pageE Ticket 2Rumi AcademicNo ratings yet

- Manual Book Avanza IndonesiaDocument327 pagesManual Book Avanza IndonesiaSMK Mitra PasundanNo ratings yet

- Watch Antim The Final Truth Free Online Vol3ioh5Document3 pagesWatch Antim The Final Truth Free Online Vol3ioh5siniwasenNo ratings yet

- Relic Knights Rulebook WebDocument64 pagesRelic Knights Rulebook Weblimsoojin100% (1)

- Stack Eg6Document4 pagesStack Eg6Juanpe HdezNo ratings yet

- Experience Guide Quarter 2 - Music 7 Lesson 8: RondallaDocument5 pagesExperience Guide Quarter 2 - Music 7 Lesson 8: RondallaLeonel lapinaNo ratings yet

- Opel 2001 Full Presspack EngDocument80 pagesOpel 2001 Full Presspack EngRazvan Secarianu0% (1)

- Unit Color Compendium 1702 Double PagesDocument144 pagesUnit Color Compendium 1702 Double PagesStarslayer RNC100% (3)

- Lesson 4.7 - Philippine LiteratureDocument24 pagesLesson 4.7 - Philippine LiteratureAlyssa BobadillaNo ratings yet

- 10d Talking Points-Eng 23072014Document20 pages10d Talking Points-Eng 23072014Liew Hao Chrng100% (2)

- Andhrasahityavim 025942 MBPDocument402 pagesAndhrasahityavim 025942 MBPRajaRaviNo ratings yet

- Datapage Top-Players2 MinnisotaDocument5 pagesDatapage Top-Players2 Minnisotadarkrain777No ratings yet