Professional Documents

Culture Documents

McKinsey - Measuring What Matters in Nonprofits PDF

Uploaded by

FeiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

McKinsey - Measuring What Matters in Nonprofits PDF

Uploaded by

FeiCopyright:

Available Formats

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 98

98

Measuring

what matters

in nonprofits

John Sawhill and David Williamson

Every nonprofit organization should measure its progress in fulfilling

its mission, its success in mobilizing its resources, and its staffs

effectiveness on the job.

ost nonprofit groups track their performance by metrics such

as dollars raised, membership growth, number of visitors, people

served, and overhead costs. These metrics are certainly important, but they

dont measure the real success of an organization in achieving its mission.

Of course, nonprofit missions are notoriously lofty and vague. The American

Museum of Natural History, for example, is dedicated to discovering, interpreting, and disseminating through scientific research and education

knowledge about human cultures, the natural world, and the universe. But

though the museum carefully counts its visitors, it doesnt try to measure its

success in discovering or interpreting knowledge. How could it? The pace of

scientific discovery hardly depends on the activities of a museumeven one

as prominent as this. Similarly, CARE USA exists to affirm the dignity and

worth of individuals and families living in some of the worlds poorest communities. Try to measure that.

Our research on 20 leading nonprofit organizations in the United States

as well as our firsthand experience with one of them, The Nature Conservancyshows that this problem is not as intractable as it may seem.

Although nonprofits will never resemble businesses that can measure their

success in purely economic terms, we have found several pragmatic

approaches to quantifying success, even for nonprofit groups with highly

ambitious and abstract goals. The exact metrics differ from organization

to organization, but this thorny problem can be attacked systematically.

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 99

CORBIS

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 100

T H E M c K I N S E Y Q U A R T E R LY 2 0 0 1 N U M B E R 2

100

To grasp the complexity of the taskand the serious problems of the

approach that most nonprofits currently use consider the experience of

The Nature Conservancy.

Bucks and acres

For 50 years, the Conservancy has had a clear mission: to preserve the diversity of plants and animals by protecting the habitats of rare species around

the world. For most of the history of this organization, it measured success

solely by the second, more tangible, part of its mission: protecting habitats.

Thus it would simply add up the

EXHIBIT 1

amount of the annual charitable

Bucks and acres: The Nature Conservancy

donations it received and the number

of acres it was protecting. These

Measurement of progress, 197199

metrics soon became enshrined as

Total income and cost of land, $ million

bucks and acres.

1971

Endowment funds

2.2

42.5

6.1

All other revenues1

Total cost of land2

13.5

225.0

1981

33.4

102.1

254.7

145.3

1991

791.7

774.9

1999

217.4

Acres preserved, millions

1971

United States

0.2

As a measurement system, bucks

and acres had a lot going for it.

Managers clearly understood how

their programs would be judged

and could act accordingly. The

board of governors liked the

emphasis on buying landan

approach that set the Conservancy

apart from other environmental

organizations: donors responded

well to the clarity and simplicity

of dollars raised and land saved.

International

1981

2.0

1991 5.5

1999

35.0

40.5

11.0

55.0

66.0

Members, thousands

1971

1981

1991

1999

28

129

600

1,049

Includes lease income, planned gifts, land sales, and donations.

Includes joint- or sole-ownership acquisition fees, payments made to

landowners to keep lands in conservation status (conservation easements),

leases, licenses, and management agreements.

Source: The Nature Conservancy

2

These metrics told a tale of success

(Exhibit 1). The Conservancythe

worlds largest private conservation

grouphas protected 12 million

acres in the United States and millions of additional acres in 28 other

countries. Last year, its membership

climbed to 1.1 million people and its

revenue to $780 million. Without

question, the upward trajectory of

these statistics bolstered the morale

of the staff, increased its motivation,

and inspired confidence among

donors.

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 101

M E A S U R I N G W H AT M AT T E R S I N N O N P R O F I T S

101

Despite this apparent success, in the early 1990s Conservancy managers

began to realize that bucks and acres didnt adequately measure the progress

of the organization toward achieving its mission. The Conservancys goal,

after all, isnt to buy land or raise

money; it is to preserve the diversity

of life on Earth. By that standard,

In the early 1990s, managers of

the Conservancy had been falling

The Nature Conservancy began

short every year of its existence. It

to realize that bucks and acres

had its successes, but the extinction

didnt really measure its progress

of species continued to spiral out

of control: one Harvard biologist,

E. O. Wilson, estimates that the extinction rate today is as high as it was

during the great extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

What particularly worried the Conservancy was the fact that species were

declining even within its protected areas. For instance, several years after

acquiring property around Schenob Brook, in Massachusetts, specifically to

protect the remaining bog turtles, the population started to shrink. It turned

out that activities outside the preserve were affecting the water on which the

turtles depended. In response, the Conservancy revisited its basic strategy.

Instead of acquiring and protecting small parcels of land that harbor rare

speciesa Noahs Ark strategy the organization began to work on preserving larger ecosystems. This approach might mean looking outside the

preserve, at conditions such as economic development, pollution, and soil

erosion. It might also mean restoring an areas natural environmental

dynamics by once again allowing wildfires or floods to do their work. Not

surprisingly, the old acres-protected measure did little to clarify the effectiveness of the new conservation strategy.

It soon became clear that the bucks measurebiased as it was toward

raising money for projects that appealed to donors but didnt necessarily

advance the organizations missionalso left much to be desired. The

Conservancy has always maintained that it is in the science business, not the

beautification business; protected areas must be chosen for their scientific

value, not for their scenic qualities or proximity to major population centers.

In 1996, the Conservancy decided to abandon bucks and acres and to develop

a better way of measuring success.

A new framework

After spending several years trying out different approachesincluding one

that involved 98 different metrics the Conservancy settled on a simple

framework for measuring performance. Known as the family of measures

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 102

T H E M c K I N S E Y Q U A R T E R LY 2 0 0 1 N U M B E R 2

102

EXHIBIT 2

The family of measures

Metrics used by

The Nature Conservancy

Mission

Impact measures

Measure progress toward the

mission and long-term objectives

that drive organizational focus

(Exhibit 2), it can be

used by any nonprofit

organization (see sidebar, Link your metrics

to your mission).

Biodiversity health

Threat abatement

Every organization, no

matter what its mission

or scope, needs three

kinds of performance

Goals

metricsto measure

Activity measures

Measure progress toward the goals Projects launched

its success in mobilizing

and program implementation that

Sites protected

drive organizational behavior

its resources, its staffs

Strategies

effectiveness on the job,

and its progress in fulCapacity measures

Measure progress at all levels of

Total membership

Tactics/

filling its mission. The

the organization, thereby enabling

Public funding for

activities

specific metrics that

it to get things done

conservation projects

Growth in private

each nonprofit group

fund-raising

Market share

adopts to assess its

performance in these

categories will differ;

an environmental organization might rate the performance of its staff by

whether clean-air or -water legislation was adopted, a museum by counting

how many people visited an exhibition. But any comprehensive performancemanagement system must include all three types of metrics. Financial metrics, such as the percentage of revenue spent on overhead and administration,

are also important management tools, but since the law requires organizations to report them, they are excluded from this framework.

Vision

Two of the three necessary types of metrics are relatively easy to create:

those that measure the mobilization of resources and those that track the

activities of the staff. Indeed, these two sets of metrics are actually similar to

The Nature Conservancys old bucks-and-acres system, and most nonprofit

organizations already have a version of them. Metrics for the mobilization

of a groups resources could include fund-raising performance, membership

growth, and market share; metrics for staff performance, the number of

people served by a particular program and the number of projects that an

organization completes.

The third kind of metricmeasuring the success of an organization in

achieving its missionis considerably more difficult to create, but, as

The Nature Conservancy discovered, it is also the most crucial.

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 103

M E A S U R I N G W H AT M AT T E R S I N N O N P R O F I T S

Link your metrics to your mission

Performance metrics can be a powerful management tool in creating incentives for staff and

managers and in ensuring that organizations

focus on accomplishing their mission. This idea

may be simple, even obvious, but very few nonprofits have systematically linked their metrics to

their mission, and too many repeat the mistake

of confusing institutional achievements with

progress toward achieving it.

The very act of aligning the mission, goals, and

performance metrics of an organization can

change it profoundly. After setting ambitious,

concrete goals for reducing cancer rates,

the American Cancer Society found that it had

to change its strategy to meet those goals.

Dr. John Seffrin, the organizations chief executive, explains: It was immediately obvious to

all of our staff that business as usual would not

get the job done and that we had to be smarter

about allocating our resources and more aggressive about trying new strategies. Our new

emphasis on advocacy, for example, is the

direct result of setting these 2015 goals. . . .

Mobilizing major public resources for cancer

research makes for better leverage than raising

all that money ourselves.

In a sector in which the commitment and motivation of the staff is paramount, the powerful

incentives that performance metrics create

shouldnt be taken lightly. The best metrics show

how any job contributes to the larger mission,

what is expected of that job, and how well the

person who holds it is doing. They also help

establish a culture of accountability.

The quantification of performance can mobilize

the staff and spur competition among employees. The ubiquitous fund-raising thermometer,

to give just one example, is a classic, effective

motivational tool. Many national organizations

especially participatory groups like the Boy

Scouts of America, Teach for America, and the

Special Olympicsmake use of statistical indicators about their membership or client base to

spark friendly competition among local chapters.

We use this information to appeal to the competitive spirit in our field people, the director of

one large youth organization explains candidly.

We want the staff in Texas to get rankled when

the staff in New Mexico brings in more people

than they do.

Such concrete measures of success are an

important marketing tool for attracting donors

and building public support. Many foundations

now demand to see the results of their investments in nonprofit organizations and will finance

only those that can give them detailed answers.

Increasingly, these funders are not satisfied with

answers that amount to little more than laundry

lists of activities. Were not grant makers;

were change makers, says a senior official

of the Kellogg Foundation. To individual donors,

focused performance measures communicate

a businesslike attitude and a high degree of

competence. Many nonprofit organizations,

such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and

the American Cancer Society, have successfully

used well-publicized performance targets to

influence public opinion and the policy agenda

of government.

103

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

104

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 104

T H E M c K I N S E Y Q U A R T E R LY 2 0 0 1 N U M B E R 2

Measuring the success of the mission

Our research has found that nonprofit organizations, despite the enormous

difficulties, can measure their success in achieving their mission. They have

three options. First, a nonprofit group can narrowly define its mission so

that progress can be measured directly. The mission of Goodwill Industries,

for example, is to raise people out of poverty through work: A hand up, not

a hand out. Goodwill can therefore measure its success simply by counting

the number of people participating in its training programs and then placed

in jobs. Its affiliates offer many programs besides those for job training, but all are linked to the core purpose of providing the poor

with employment. By contrast, Catholic Charities and World

Vision, though comparable organizations, have broader

antipoverty missions that are impossible to quantify directly.

Nonprofit groups that take the option of defining their mission

narrowly must avoid the trap of oversimplifying it and treating

the symptoms rather than the cause of a particular social problem. Until recently, the mission of the US charity Americas Second

Harvest was to feed the hungry, and it could easily quantify its success by counting the amount of food it collected and distributed. The

organizations leaders have since decided to expand their activities to address

the underlying problem and have therefore adopted a more ambitious mission: ending hunger in the United States. Advocacy and public-education

efforts have become a larger part of the charitys agenda, and the organizations success will be judged not only by statistics on hunger but also by

changes in public attitudes as expressed in opinion surveys.

A second option for measuring the success of an organization in achieving

its mission is to invest in research to determine whether its activities actually

do help to mitigate the problems or to promote the benefits that the mission

involves. The nonprofit organization Jump$tart Coalition, dedicated to

improving the educational outcomes of poor children, is a good example

of this approach. One of the biggest challenges facing the federal education

program Head Start is that many children leave it, at age five, still unprepared

for school. Jump$tart developed a program to help Head Starts lowest

achievers, at age four, improve their basic literacy skills. Statistical studies,

updated periodically, have clearly shown that Jump$tart graduates enter

kindergarten better prepared than do similar children who didnt participate

in the program and, more important, that its graduates have better educational outcomes throughout primary school. With the link between the

organizations program and mission firmly established, Jump$tart can now

measure its success by the number of children in its programs.

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 105

M E A S U R I N G W H AT M AT T E R S I N N O N P R O F I T S

105

Nonprofit organizations with less quantifiable missions will find this

approach more difficult. The mission of the Girl Scouts of the USA, for

instance, is to help young girls reach their full potential as citizens. The

Girl Scouts commissioned a large-scale study concluding that its members

do indeed become more successful,

responsible citizens than do women

who hadnt been Scouts.1 The study

Since the Girl Scouts now has

got around the problem of defining

evidence that its programs work, it

the term responsible citizens by

measures success by counting

using proxies such as professional

the number of girls in its programs

success, divorce rates, and participation in civic life (for instance,

voting), as well as self-reported measures of happiness and satisfaction. It

did not, however, control for the problem of selection bias: girls who signed

up for the Girl Scouts might have become more successful citizens even if

they hadnt done so, because of their personal characteristics or family background. Nonetheless, the organization does have evidence, albeit fuzzy, that

its programs work. It now measures its success in achieving its mission by

counting the number of children (particularly from historically underrepresented demographic and socioeconomic groups) in its programs.

For most nonprofit organizations, however, narrowing the scope of the mission isnt an option and investing in research into outcomes isnt feasible. The

Nature Conservancy, for example, could conceivably calculate changes in the

Earths total biodiversity, but the benefits of that approach wouldnt justify

the astronomical cost of doing so. The Conservancys work has at best only a

modestif not imperceptibleeffect on global biodiversity, which is affected

on a far greater scale by other factors, such as tropical deforestation, climate

change, and the conversion of habitats.

These nonprofits have a third option for measuring their success in achieving their mission: they can develop microlevel goals that, if achieved, would

imply success on a grander scale. The Nature Conservancy cant measure

global biodiversity, but it can closely examine biodiversity in the areas it

manages. So it has chosen to determine its success in achieving its mission

by gauging the success of its biodiversity health and threat-abatement efforts

in the areas it protects. Both are relatively easy to measure: to measure

the success of the biodiversity-health effort, the Conservancy evaluates the

condition of all the plants and animals it is trying to save against a baseline

set of data established by existing scientific surveys; to measure the success

of its efforts to control threats to biodiversity, the Conservancy tracks its

1

Defining Success: American Women, Achievement, and the Girl Scouts, Girl Scouts of the USA, September

1999. Louis Harris and Associates conducted the research.

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 106

T H E M c K I N S E Y Q U A R T E R LY 2 0 0 1 N U M B E R 2

106

EXHIBIT 3

Assessing mission success: Mixed results

The Nature Conservancys self-reported measure of mission

success across all US sites, 2000, percent of sites

Aggregate biodiversity health

100% = 62 sites

Poor

Very good

6

Different conservation

targetssuch as the

quality of the terrain or

plant lifeare measured

at each site. Targets are

ranked according to size,

condition, and landscape

context on a scale from

very good to poor.

programs to counter the most critical threats to environmental health

in particular places (Exhibit 3). If

the organization meets these two

goals in all its project areas, it will

ultimately have a lasting, positive

impact on biodiversity.

One of the benefits of this approach

is that microlevel goals can be

50

Good

simple and clear. The mission of the

Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF)

is to preserve the health of the

Chesapeake estuary. In 1995, CBF

Aggregate threat

worked out nine indicators of the

100% = 62 sites

Each site is surveyed for

bays health, such as water clarity,

levels of threat to the

Low

1

conservation targets.

levels of dissolved oxygen, migratory

Medium

Threats are ranked on a

22

scale from very high to

fish populations, and the size of the

low. Examples of threats

Very

40

surrounding wetlands. It collected

include:

high

Alien, invasive species

baseline data for each indicator and

Rise in sea level

37

Road construction

then set specific ten-year targets rep Home, resort

High

development

resenting significant progress for the

bay. The power of this approach lies

Source: The Nature Conservancy

in its simplicity: government agencies

already collect information about the

nine indicators, at no cost in time or money to CBF. The general public and

potential donors easily understand the indicators: adding 125,000 acres of

wetlands to the bays watershed by 2005 is quite clear. CBFs president holds

an annual press conference to issue a report card on the bays health, thus

increasing public awareness and mobilizing support. If CBF reaches its goal

for each of the nine indicators, it will have met its broader objective of preserving the health of the bay.

Fair 42

What about organizations with more ambiguous and ambitious social goals?

Preventing cancer and reducing the anguish and deaths from it are far more

difficult tasks. How can the American Cancer Society (ACS) distinguish

between its impact and the effect of the many other variables that influence

cancer rates? The management of ACS reasoned that it doesnt matter who

deserves credit for any decline in cancer rates. What does matter is that ACS

should use its own resources in the most effective possible way. It has thus

set specific goals: reducing cancer mortality rates by 50 percent and the overall incidence of cancer by 25 percent as of 2015. Because empirical research

26934-(098-107)Q2_Metrics v5

4/11/01

3:13 PM

Page 107

M E A S U R I N G W H AT M AT T E R S I N N O N P R O F I T S

shows that prevention, screening, and educational programs are highly effective in reducing both the incidence of and mortality from cancer, ACS has

moved away from research and toward prevention and awareness programs.

With creativity and perseverance, nonprofit organizations can measure their

success in achieving their missionby defining the mission to make it quantifiable, by investing in research to show that specific methods work, or by

developing concrete microlevel goals that imply success on a larger scale.

Given the diversity of the organizations in the nonprofit sector, no single

measure of success and no generic set of indicators will work for all of them.

Nonetheless, our experience and research indicate that these organizations

canindeed, must measure their performance and track their progress

toward achieving their mission. They owe their clients, their donors, and

society at large nothing less.

The late John Sawhill was a director in McKinseys Washington, DC, office; David Williamson, director of communications at The Nature Conservancy, is a fellow at the Aspen Institute, in Washington,

DC. Copyright 2001 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

107

You might also like

- 1501 - PWC - M&a 2014Document39 pages1501 - PWC - M&a 2014FeiNo ratings yet

- 1304 Roland Berger Maximizing The Value of Chinas MuseumsDocument16 pages1304 Roland Berger Maximizing The Value of Chinas MuseumsFeiNo ratings yet

- BBC - How To Win in China - Top Brands Share Tips For SuccessDocument3 pagesBBC - How To Win in China - Top Brands Share Tips For SuccessFeiNo ratings yet

- 1304 Roland - Berger - The - New - Tobacco - Products - Directive - Potential - Economic - Impact - 20130424 PDFDocument52 pages1304 Roland - Berger - The - New - Tobacco - Products - Directive - Potential - Economic - Impact - 20130424 PDFFeiNo ratings yet

- 1311 BCG - The Trust Advantage - How To Win With Big DataDocument18 pages1311 BCG - The Trust Advantage - How To Win With Big DataFeiNo ratings yet

- 1311 BCG - The Trust Advantage - How To Win With Big DataDocument18 pages1311 BCG - The Trust Advantage - How To Win With Big DataFeiNo ratings yet

- Partnerships, M&a in ChinaDocument2 pagesPartnerships, M&a in ChinaFeiNo ratings yet

- 2011 Chinese Consumer Report EnglishDocument48 pages2011 Chinese Consumer Report EnglishFeiNo ratings yet

- BCG Case Interview PreparationDocument18 pagesBCG Case Interview PreparationPedro Almeida100% (13)

- 1206 - BCG - Measuring A Museum's PerformanceDocument5 pages1206 - BCG - Measuring A Museum's PerformanceFeiNo ratings yet

- Most Innovative Companies 2013 Sep 2013 Tcm80-144787Document27 pagesMost Innovative Companies 2013 Sep 2013 Tcm80-144787Andrés MaierNo ratings yet

- Building A Better Income StatementDocument4 pagesBuilding A Better Income StatementAriana FlorNo ratings yet

- 11 - E - Y - Cleantech Matters - Moment of Truth For Transportation ElectrificationDocument44 pages11 - E - Y - Cleantech Matters - Moment of Truth For Transportation ElectrificationFeiNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Plug - Finding Value in The Electric Vehicle Charging EcosystemDocument44 pagesBeyond The Plug - Finding Value in The Electric Vehicle Charging EcosystemAlfredo González NaranjoNo ratings yet

- 1302 Roland Berger - Automotive InsightsDocument52 pages1302 Roland Berger - Automotive InsightsFeiNo ratings yet

- McKinsey Perspective On Chinas Auto Market in 2020 PDFDocument16 pagesMcKinsey Perspective On Chinas Auto Market in 2020 PDFMiguel Castell100% (1)

- 1401 PWC - M&a 2013 Review & 2014 Outlook - ChinaDocument40 pages1401 PWC - M&a 2013 Review & 2014 Outlook - ChinaFeiNo ratings yet

- 1401 BCG Winning in Africa PDFDocument36 pages1401 BCG Winning in Africa PDFFeiNo ratings yet

- 1308 McKinsey - M - A As Competitive Advantage PDFDocument5 pages1308 McKinsey - M - A As Competitive Advantage PDFFeiNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Freelance Digital Marketer in Calicut - 2024Document11 pagesFreelance Digital Marketer in Calicut - 2024muhammed.mohd2222No ratings yet

- S G Elion ComplaintDocument25 pagesS G Elion Complainttimoth31No ratings yet

- Arshiya Anand Period 5 DBQDocument3 pagesArshiya Anand Period 5 DBQBlank PersonNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media on Grade 12 STEM Students' Academic PerformanceDocument41 pagesImpact of Social Media on Grade 12 STEM Students' Academic PerformanceEllie ValerNo ratings yet

- Lesson 01: Communication: Process, Principles and Ethics: OutcomesDocument9 pagesLesson 01: Communication: Process, Principles and Ethics: OutcomesMaricris Saturno ManaloNo ratings yet

- Crla 4 Difficult SitDocument2 pagesCrla 4 Difficult Sitapi-242596953No ratings yet

- Ecclesiology - and - Globalization Kalaitzidis PDFDocument23 pagesEcclesiology - and - Globalization Kalaitzidis PDFMaiapoveraNo ratings yet

- Objectives of Community Based RehabilitationDocument2 pagesObjectives of Community Based Rehabilitationzen_haf23No ratings yet

- Sūrah al-Qiyamah (75) - The ResurrectionDocument19 pagesSūrah al-Qiyamah (75) - The ResurrectionEl JuremNo ratings yet

- EMS Term 2 Controlled Test 1Document15 pagesEMS Term 2 Controlled Test 1emmanuelmutemba919No ratings yet

- SecureSpan SOA Gateway Gateway & Software AGDocument4 pagesSecureSpan SOA Gateway Gateway & Software AGLayer7TechNo ratings yet

- BPI Credit Corporation Vs Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesBPI Credit Corporation Vs Court of AppealsMarilou Olaguir SañoNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management 14th Edition Mathis Test BankDocument23 pagesHuman Resource Management 14th Edition Mathis Test BankLindaClementsyanmb100% (13)

- Quarter4 2Document13 pagesQuarter4 2Benedick CruzNo ratings yet

- PROJECT CYCLE STAGES AND MODELSDocument41 pagesPROJECT CYCLE STAGES AND MODELSBishar MustafeNo ratings yet

- 111Document16 pages111Squall1979No ratings yet

- RGNULDocument6 pagesRGNULshubhamNo ratings yet

- The Bloody Pulps: Nostalgia by CHARLES BEAUMONTDocument10 pagesThe Bloody Pulps: Nostalgia by CHARLES BEAUMONTGiles MetcalfeNo ratings yet

- Company Profile: "Client's Success, Support and Customer Service Excellence Is Philosophy of Our Company"Document4 pagesCompany Profile: "Client's Success, Support and Customer Service Excellence Is Philosophy of Our Company"Sheraz S. AwanNo ratings yet

- Residential Status Problems - 3Document15 pagesResidential Status Problems - 3ysrbalajiNo ratings yet

- Adr Assignment 2021 DRAFTDocument6 pagesAdr Assignment 2021 DRAFTShailendraNo ratings yet

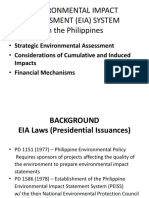

- Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia) System in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment (Eia) System in The PhilippinesthekeypadNo ratings yet

- HBOE Detailed Agenda May 2021Document21 pagesHBOE Detailed Agenda May 2021Tony PetrosinoNo ratings yet

- Cracking Sales Management Code Client Case Study 72 82 PDFDocument3 pagesCracking Sales Management Code Client Case Study 72 82 PDFSangamesh UmasankarNo ratings yet

- Weathering With You OST Grand EscapeDocument3 pagesWeathering With You OST Grand EscapeGabriel AnwarNo ratings yet

- William Allen Liberty ShipDocument2 pagesWilliam Allen Liberty ShipCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- A400MDocument29 pagesA400MHikari Nazuha100% (1)

- Interim Rules of Procedure Governing Intra-Corporate ControversiesDocument28 pagesInterim Rules of Procedure Governing Intra-Corporate ControversiesRoxanne C.No ratings yet

- Republic Vs CA and Dela RosaDocument2 pagesRepublic Vs CA and Dela RosaJL A H-Dimaculangan100% (4)

- International Electric-Vehicle Consumer SurveyDocument11 pagesInternational Electric-Vehicle Consumer SurveymanishNo ratings yet