Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Integrating Sustainability Acctg Into MGT Practice-Main

Uploaded by

Nero ShaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Integrating Sustainability Acctg Into MGT Practice-Main

Uploaded by

Nero ShaCopyright:

Available Formats

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices

Carol A. Adams a, , Geoffrey R. Frost b

a

Faculty of Law and Management, La Trobe University, Victoria 3086, Australia

b The University of Sydney, Australia

Abstract

This paper examines the process of developing key performance indicators (KPIs) for measuring sustainability performance

and the way in which sustainability KPIs are used in decision-making, planning and performance management. Interviews were

conducted with personnel from four British and three Australian companies. The findings indicate that the organisations are

integrating environmental indicators, and increasingly also social indicators, into strategic planning, performance measurement and

decision-making including risk management. However, the sustainability issues on which our sample focus and the management

operations on which they impact vary considerably. This has implications for the development of practice, voluntary guidelines and

legislation.

2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility (CSR); Decision-making; Key performance indicators (KPIs); Performance measurement; Sustainability;

Sustainability reporting

1. Introduction

Increasing attention and concern over the social and environmental impact of business and the impact of social and

environmental issues on business has led a number of companies to actively account for and manage their sustainability

footprint. Recent emphasis has been on the integration of ethical, social, environmental and economic, or sustainability

issues within corporate reports. This has been referred to as triple bottom line (Elkington, 1997), or sustainability

reporting (Global Reporting Initiative, 2000). The movement towards integrating these issues in reporting is evidenced

by the publication of more comprehensive corporate sustainability reports supported by guidelines such as those of the

Global Reporting Initiative (2006). However, there remains concern about the limited adoption of integrated reporting,

the completeness and credibility of these reports (Adams, 2004) and the motives of managers preparing them (ODwyer,

2002, 2003).

Given that many researchers in the field of sustainability reporting are motivated by a desire to see improvement in

the sustainability performance of organisations (Adams & Larrinaga Gonzalez, 2007) there has been surprisingly little

research into sustainability reporting processes and the extent to which data collected is used in decision-making within

organisations. Instead, assumptions have been made about corporate motives and processes from an examination of

corporate disclosures, often without reference to the broader social, political and economic context in which those

disclosures are made. Responding to calls for more research which engages with reporting organisations (Adams,

2002; Adams & Larrinaga Gonzalez, 2007; Parker, 2005), this study sheds light on the extent to which sustainability

Corresponding author. Tel.: +61 3 9479 1667; fax: +61 3 9479 3278.

E-mail address: c.adams@latrobe.edu.au (C.A. Adams).

0155-9982/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.accfor.2008.05.002

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

289

accounting and reporting functions are integrated into the planning, performance management and risk management

operations of organisations. Specifically it considers: how organisations are developing and refining key performance

indicators (KPIs) and benchmarking various aspects of performance; and, how sustainability KPIs are being utilised

to influence management decisions.

Our study involved interviews with personnel from three Australian and four British organisations that are known for

best practice reporting or management on aspects of ethical, social, environmental and economic issues. It contributes

to the prior literature by revealing the diversity in: internal processes; the mode of integration into decision-making;

and, the focus of reporting and data collection.

2. Prior literature

Considerable doubt has been cast on the extent to which many sustainability reports accurately and completely

portray corporate social and environmental impacts (Adams, 2004; Adams & Harte, 1998; ODwyer, 2002, 2003). Yet

there is recent evidence that some organisations are using the data they collect in the course of preparing their sustainability report and internal reports on social and environmental impacts to monitor performance and reward managers

and that such data is informing corporate planning and decision-making (see, for example, Adams & McNicholas,

2007; Albelda-Perez, Correa-Ruz, & Carrasco-Fenech, 2007). There is an increasing understanding of the dependence

of organisations on societys acceptance of their overall contribution and impacts to a broad range of stakeholders. It is

increasingly the case that, in order to survive and thrive, organisations must make decisions which serve the interests

of the environment and society. A growing number of organisations have been forced to respond to concerns about

their social and environmental impacts including, for example, James Hardie, Nestle, Nike, and Shell. Data collected

by organisations on their social and environmental impacts does not ensure that managers will make decisions which

appropriately balance social, environmental or economic impacts or appropriately prioritise the various stakeholder

claims, but it can provide the basis for more informed decision-making. Business case proponents of an approach where

decision-making is informed by social and environmental impact data, would expect to see a convergence between

corporate and society interests. There are examples of companies leading the way by influencing society to be more

environmentally friendly. For example, energy and water companies provide customers with data on resource use and

suggestions as to how to reduce it and manufacturing companies encourage recycling of packaging.

The integration of various systems is seen by prominent researchers as the final stage in the evolution of a system

to assist strategic thinking within the firm (Kaplan & Cooper, 1998; Schaltegger & Burritt, 2000). A focus on environmental performance developed initially to meet compliance requirements (Dias-Sadinha & Reijnders, 2001; Johnston

& Smith, 2001) and scientific and societal interests (Kolk & Mauser, 2002). Improved performance was demonstrated

using physical measures alone, limiting the analysis of benefits and associated financial implications (Koehler, 2001).

There have been few examples in the literature of data collected for sustainability reporting being linked to performance evaluation and strategic alignment of organisational management systems (Dias-Sadinha & Reijnders, 2001;

Ditz, Ranganathan, & Banks, 1995; Epstein, 1996; Koehler, 2001), perhaps reflective of the limited exploration and

understanding of system design and performance alignment within the mainstream management accounting literature

(Chenhall, 2005; Chenhall & Langfield-Smith, 2003; Ittner, Larcker, & Randall, 2003), or the limited research on

internal drivers for the development of sustainability management (Delmas & Toffel, 2004; Harris, 2007).

Research on social and environmental (including occupational, health and safety) performance has identified the

prominence of non-financial performance indicators (Johnston & Smith, 2001) concerned with measuring physical

impact. Reducing physical impact has equated to improved performance, but does not necessarily result in improved

strategic management. For example, physical non-financial measures are reviewed in isolation, with management

attention focused on meeting predetermined minimum requirements. Broader implications, for both the organisation

and the environment, are often disregarded. Effective evaluation of alternate approaches to managing sustainability

performance must consider not only the physical measures of performance, but also the financial aspects (Bennett &

James, 1998a,b; Koehler, 2001; Schaltegger & Burritt, 2000). Despite this, research on environmental management

accounting (EMA), has found that adoption of EMA is limited for many companies. For example, Frost and Wilmshurst

(2000) observed that Australian companies were developing procedures to collate accounting data only for issues perceived to be of significant environmental importance. Similarly Parker (2000) found that the environmental accounting

techniques such as cost recognition were in a far more elementary stage than the application of environmental policies,

management, impact statements and audit.

290

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

Prior research indicates that accounting for environmental issues may not be as advanced as other monitoring

and measurement processes of an organisations environmental management system. Where environmental issues

are regarded as important, they are being managed, but accounting information is not being used in the decisionmaking process (Schaltegger & Burritt, 2000) suggesting that environmental management is based on the physical

processes, inputs and outputs. This is reflected in many of the environmental management accreditation schemes

such as the ISO14000 series and EMAS. If sustainability reporting is to lead to improvements in sustainability

performance, organisations must seek to integrate both physical and financial performance indicators into various

aspects of their management functions. An example of how this might be achieved is provided by Koehler (2001)

who examined accounting for environment, health and safety (EHS) at Baxter International. The motivation for the

development of the accounting system was to provide data on the cost of EHS issues for the firm and to facilitate evaluation of performance of various systems, using both physical and financial data. The additional financial

analysis provided benefits through a greater focus on processes. (For example, in Baxter managers were favouring

placing workers on restricted duties as opposed to work days lost which had clear financial implications. Additional financial analysis however allowed managers insights as to the true costs of restricted duties.) The cost data

also became critical for investment strategy in new programs. . . which may currently not be considered viable or

important enough (Koehler, 2001, p. 235). Accounting for social issues changed the focus in Baxter from outputs

(work days lost) to inputs (activities, i.e. how many nurses are required). For Baxter it was a move from focusing on compliance and external reporting, to developing performance measures that were used to craft corporate

strategy.

The inclusion of data on ethical, social, environmental and economic information into decision-making processes

is a significant progression for an organisation (Koehler, 2001). Without consideration of such data, it is difficult to

see how organisations can improve their sustainability performance. In order to assist decision-making and improve

sustainability performance, KPIs measuring financial, physical and even attitudinal aspects of performance, must be

used, not only as a record of past performance, but also as a means of evaluating risk, developing plans and determining

performance-based rewards. Similarly, possible future impacts of particular decisions should be calculated.

The task of identifying appropriate KPIs should be done in consultation with key stakeholders (ISEA, 1999a,b;

Searcy, McCartney, & Karapetrovic, 2008). Without such consultation and regular engagement corporate reports are

unlikely to be complete as regards material impacts of key stakeholder groups. The AA1000 process standard suggests

stakeholders should be involved in the selection and review of KPIs and that meaningful stakeholder engagement is one

where stakeholders are involved in defining the terms of the engagement and are able to express their view without fear

or penalty (ISEA, 1999a,b). However, in examining statements about new governance processes in CSR reports, specifically those related to the role of stakeholder engagement, Cooper and Owen (2007, p. 657) note: Clearly corporate

governance mechanisms have not evolved in such a way that stakeholder accountability, as opposed to (enlightened?)

stakeholder management, may be established. Such an observation raises questions as to the organisations ability or

capacity to engage with stakeholders.

In this exploratory research study we examine how KPIs are developed and used in decision-making across corporate

operations.

3. Research method

This study examines three Australian (X, Y and Z) and four British companies (A, B, C and D) that have either

been actively engaged in sustainability reporting for a number of years and considered by the authors to be adopting

elements of best practice approaches to sustainability reporting and/or managing sustainability performance.1 This

involves: incorporating sustainability issues into strategic and operational planning across the organisation; linking

sustainability values, objectives and targets; measuring and reporting performance against targets; benchmarking

performance; involving stakeholders in determining KPIs and reviewing performance; completeness of reporting

with regard to all material impacts, whether positive or negative, on key stakeholder groups; provision of a fair

portrayal of performance on sustainability issues to stakeholders; and, a robust external assurance process. The case

study organisations included two banks, three utility companies, one telecommunications company and one forestry

1

Both authors have considerable experience in analysing sustainability reports and case study research experience with organisations.

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

291

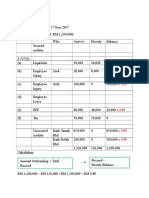

Table 1

British interviewees

Name of company (sector)

Date

Designation of interviewees

A: Bank

29 September 2003

B: Utility

2 October 2003

C: Utility

24 September 2003

D: Utility

30 September 2003

Manager, Sustainability Reporting & Diversity

Sustainability Manager

Corporate Environment Director Energy and Environment

Director

Senior Environmental Scientist Environment, Quality and

Sustainability CSR/Strategic Projects Manager

Head of CSR Senior Environmental Advisor Group safety

manager Supply chain specialist Green Transport

co-ordinator

management entity. Our study is exploratory. The choice of British and Australian companies is based on the locations

of the researchers.

Interviews were conducted during 2003 and 2004 with a total of 15 organisational participants involved in the development of sustainability accounting and reporting. Tables 1 and 2 provide details of interviewees roles. The industry

of each organisation is provided, but otherwise minimal information is disclosed on each organisation due to the need

to maintain confidentiality. The interviews were semi-structured and covered: the motivation for sustainability reporting; the personnel involved; how KPIs were developed, refined and used; how TBL or sustainability accounting

is being integrated into management functions such as decision-making, strategic management and planning, performance management and risk management; and, perceived problems, advantages and future directions with regard to the

integration of sustainability reporting into management functions. The minimum time spent with an organisation was

one and a half hours and the maximum a full day. The interviews explored processes rather than specific performance

outcomes.

4. Results

To better understand the outcome of the interviews, data from the transcribed interviews were classified under

various themes: the motivation and personnel behind the development of sustainability reporting; the development

and use of KPIs relating to social and environmental performance; integrating sustainability reporting processes with

performance measurement and integrating social and environmental issues into decision-making; and, future directions.

The themes were chosen to assist in addressing our overall research question. We have analysed our results according

to these themes. We have identified each company by letter (except where we felt this might lead to identification of

the company) in order to demonstrate that we are drawing from data from across our sample. It is not our intention to

tell a story about individual companies, but rather to present the different manner in which issues are dealt with across

our sample companies.

4.1. Motivation for sustainability reporting

The companies interviewed cited business, moral and practical reasons for commencing to report on sustainability

issues. The reasons given included: the high impact nature of their operations on the environment (C, D, Y); to be

accountable to, and build trust with, key stakeholders such as NGOs and local communities (B, C, X, Z); privatisation

Table 2

Australian interviewees

Name of company (sector)

Date

Designation of interviewees

X: Bank

Y: Telecommunications

Z: Forestry

21 June 2004

27 May 2004

14 July 2004

Group Public Relations Manager

General Manager, Public & Government Affairs

Director, Environmental Management and Forest Practices

Directorate Sustainability Project Manager

292

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

and resulting competition (Y); to influence business leaders and key opinion formers (C); differentiating themselves

from competitors with a view to increasing market share and improving profitability (A); following competitors (C);

and, influence of tools such as the Business in the Community (2000) Winning with Integrity model and the GRI

Guidelines (Global Reporting Initiative, 2000) (D).

Company A reported that since commencing to produce sustainability reports, the banks profitably has improved

and its ethical policy is attracting good staff. Y observed that the process of collecting data itself was a catalyst for

change towards improved performance within the organisation. This occurs both because the data becomes visible and

because the existence of KPIs which are broken down by business units results in competition between the business

unit managers to improve their performance.

Even with our small sample of companies considerable diversity exists as to the initial motivating factors for

considering reporting on social and environmental issues. There were three main emphases, all concerned with the

business case: strategic in terms of stakeholder relations or differentiating themselves from competitors; responsive,

i.e. responding to a change or an issue such as a financial crises or change in community concerns; or, following, i.e.

being led by competitors or NGO or government body initiatives.

4.2. Sustainability reporting teams

The role(s) responsible for developing the sustainability report varied across our sample: General Manager of

Public and Government Affairs (Y); Group Director of Communications (B); Head of Corporate Communications

(X); Head of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Senior Environmental Advisor jointly (D); Manager for

Sustainability Reporting and Diversity (A). The differing organisation and structure of the sustainability reporting/performance functions was reflected in the diversity of ways in which their sustainability reporting function

developed and the differing capacity and focus of their efforts to improve and manage sustainability performance.

There are two key departments involved in sustainability issues at C (a British utility company), Environment,

Quality and Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The former has about 50 staff and the latter

6. A number of staff have dual reporting lines so, for example, the Head of Environment, Quality and Sustainability

reports to the Managing Director of one of the UK companies and the Director responsible for Group CSR. The

environmental champion in each business has a reporting line to the Managing Director of the business and to the Head

of the Environment, Quality and Sustainability Group. The CSR Team has weekly or fortnightly meetings.

In D (another British utility company), the Head of CSR, who focuses primarily on social and community issues, and

the senior environmental advisor work together on developing and monitoring the sustainable development policies,

strategy and plans. The CSR role was created in the late 1990s as CSR became more of a corporate focus and now

reports to CSR at group level. Prior to the creation of that role there was no formal co-ordination of CSR activities.

The co-ordination function is supported by people in the businesses who have sustainable development or CSR as

about 1015% of their roles. These people are responsible for CSR in their respective businesses and meet together

approximately once every 6 weeks. Whilst in C, staff have a clear dual reporting line, in D there is more ambiguity.

The Head of CSR was unclear as to the extent to which the 1015% of the role concerned with CSR and sustainable

development co-ordination was assessed by the business line managers. A number of focus groups have now been

created with one looking at the Corporate Responsibility Index (Business in the Community, 2004).2 However, there

are no formal controls monitoring staff involvement in these activities or in the collection of data for external reporting.

Instead they rely on the motivation of the individual staff members contrasting the more formal approach in C (another

British utility). The CSR Steering Group, chaired by the Chief Executive Officer, meets two or three times a year and

has ultimate responsibility for the development of KPIs facilitated and driven forward by the Senior Environmental

Advisor. The Group Safety Manager, in addition to responsibility for group safety issues, is also responsible for the

implementation of sustainable development policy in the non-regulated businesses internationally and has an input

into sustainability reporting.

The sustainability project manager in Z (an Australian forestry company) is one of two members of the sustainability

group established by the CEO 4 years previously to devise and implement strategies concerned with the sustainability

2

D uses the Business in the Community Winning with Integrity model (Business in the Community, 2000).

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

293

impacts of Zs activities. One of the first projects of that group was to develop a sustainability report by broadening the

scope of the Environment and Social Values Report that was first produced in 1998. The group have now extended their

remit beyond data collection and the write up of the sustainability report to the development of systems that facilitate

consistency and comparability of data.

A (a British bank) has 13 staff in its Sustainable Development Team. The Manager for Sustainability Reporting

and Diversity has a team of three working on the sustainability report, two Sustainable Development Managers and

one Diversity Manager. In contrast, primary responsibility for reporting of issues relating to sustainability in X (an

Australian bank) lies with corporate communications. Reporting through the annual report and web-site is limited,

with reporting being more direct and locally focused.

There is little consistency across our sample with regard to the commitment of resources or personnel to either the reporting function or the degree of formality or informality with respect to reporting lines

for staff involved in CSR and CSR reporting activities in the more complex organisations. Furthermore, the

focus of attention varied with some organisations more concerned with internal process and developing the

appropriate culture (X and D), others focussing on technical aspects of data collection (Z and C) and yet

others focussing on reporting, viewing it as an important means of communication to external stakeholders

(Y, A and B).

4.3. How the KPIs were developed

The development of KPIs in our sample began in the early 1990s in the high environmental impact (i.e. utility

and forestry) companies. In all but one of our sample the process has become more structured and formalised. The

exception to this was company X (Australian bank) which, in the previous section we noted did limited sustainability

reporting through the annual report and web site. Company X argued that reliance upon the organisational culture as

an informal mechanism to align actions has in the past proved an effective mechanism for management. However,

the recent growth experienced by the company is now placing considerable pressure upon the corporate culture to

continue as an effective means of control and transfer of information within the organisation. This pressure is coming

from a number of areas, including the employment of staff from other banking organisations which have a different

approach and culture, to the breakdown of the close knit relationship between staff that existed when the organisation

was smaller:

Even just twenty years ago this organisation was a very small tightly knit group. I mean it was your classic

sort of everyone knows everyone else. So you had a corporate culture that was very tight, very long standing,

very well understood. . . from top management right down to the counter stuff. Twenty years later youve got an

organisation thats ten times bigger with branches right across Australia, youve got a very different organisation.

(New staff) coming from there (other banks). . . theres a period of time when theres this wrestle between our

culture and what they think oh, well we did it that way over there we should just bring that in because that

works. Well no thats not our way of doing it. Thats not the (Company X) way and theres a bit of a time, while

they adjust and understand and some of them dont always get there fully.

The organisation is countering this pressure on the corporate culture via various means, including a proactive

managing director who continually pushes the corporate culture,

. . .people change the organisation and strategies are very strongly led by our managing director and I know one

of his key indicators to him is perhaps a strategy so deeply embedded within the organisation that when he moves

on it cant be unravelled.

and the assignment of managers fully embedded with the Company X culture to regions where there appear to be

problems with the maintenance of the underlying culture.

One of our regional managers for example who has been working in an inter-state office for the lasts five years

comes back to X . . . youll hear them say Right, we need to find a (company X) person to put back in over

there. . . . so theres still this notion of a (company X) person being a person whos deeply embedded with the

culture to take it back to the inter-state office and make sure theres a cultural influence there and youll still hear

that around here a lot.

294

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

Stakeholders, external groups as well as staff, were involved in the development of KPIs in all our sample organisations. Company C (British utility company) used a consultant to assist in engaging with stakeholders and an

environmental NGO to assist in developing the KPIs. Company Z (Australian forestry company) argued that it had

become increasingly difficult to engage stakeholders who have demands on their time from a number of organisations.

To combat this, Company B (British utility company) relied on stakeholder consultation by the industry group with

organisation specific KPIs added. Companies also made reference to the GRI Guidelines and other companies reports

as being influential in determining their KPIs.

Issues that our case companies were currently dealing with were: adaptation of KPIs to other geographical regions

with different cultures and values; development of social and economic indicators which in most cases trailed behind

environmental KPIs; developing targets and ensuring that corporate values, objectives and targets were linked; comparability and consistency across reporting regions. The latter issue resulted in the development and introduction of a

standardised reporting framework in company Z (Australian forestry company):

. . . we were having big problems with the information coming from 12 different regions . . . making sure everything added up . . . it was horrendous. And out of the workshop that we had in 2001 was this desire I guess to

stream line the data collection process . . . And in developing that system it really made us focus on descriptions

about information that people had to put in and in doing that we get a lot of comments from people about I dont

understand what this indicator means, what information do I put into it, and how do I make sure its the same

every year that sort of thing. And so developing that system has really made us think about whats the indicator,

why are we collecting it, whats it going to be used for?

In company B (British utility company), KPIs are used to identify long run business trends and for this reason they

remain constant and the method of calculation does not change.

The issue of adaptation of KPIs to other geographical regions with different cultures, values and priorities is a complex one. In one company, overseas businesses are given considerable leeway to develop priorities

appropriate to their environment. There are contractual requirements which are regularly reviewed, suggestions

beyond those are made by head office and projects are undertaken at the business discretion involving, for

example, work in the community and re-establishing rain forest. Another company in the sample operates in a

wider geographical area and the interviewees reported that, on becoming an international organisation, the KPIs

were reviewed. They acknowledged that some of the KPIs were inappropriate or irrelevant in some areas. For

example, this company operates in one country where the key issue is supplying clean, safe drinking water.

They deal with differing country contexts by having a set of global KPIs on issues of significant environmental impact and local ones are added by overseas businesses as appropriate. This approach appears to be

supported by the findings of Belal and Owen (2007) who warn against the adoption of codes and standards

in lesser developed countries which have been developed for the benefit of stakeholders in western developed

nations.

Interviewees in companies Y (Australian telecommunications company) and Z (Australian forestry company)

stressed that external reporting had had a strong and positive impact in focusing attention on performance; the development of performance measures; and, the issues which were managed. The interviewees in those companies that

had been reporting since the early to mid-1990s did not draw this out, presumably because the interviewees were not

employed with the organisations at the time.

Y (Australian telecommunications company) admitted having difficulty in quantifying performance, particularly

on the social dimensions which are important to stakeholders for its industry. Environmental impact measurement has

also proved difficult due to lack of embedded technology necessary to accurately measure emissions. Once data is

collected there is still a question as to how such data could be used:

. . .so enormous amount of debate internally is going on around how we measure stuff and putting in place the

internal platforms to ensure that measurement is rigorous.

The importance of this internal debate is particularly pertinent when there remain questions as to the underlying

meaning of the data. As indicated by the interviewee:

. . . the culture of this organisation is excessively qualitative and analysis is considered to be very important. We

value the insights that come from detailed analysis of whats going on . . .

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

295

As a consequence of this process of analysis of qualitative data the company has revisited the activities

undertaken to support environmental and community initiatives. For example, initiatives (such as sponsorship

of environmental programs) that are not directly related to the keys issues of the business are now no longer

supported.

In summary, our sample used a number of different approaches to engaging stakeholders who were facing a

variety of different issues in developing and reviewing KPIs (adaptation of KPIs to other geographical regions

with different cultures and values; development of social and economic indicators which were generally underdeveloped compared with environmental KPIs; developing targets and ensuring that corporate values, objectives and

targets were linked; comparability and consistency across reporting regions). The differing approaches and issues

reflected the different size and complexity of the sample organisations, the differing geographical areas covered

and the variety of industry groups in our sample. Leadership is a common feature across our case study organisations, but each is grappling with other capacity building factors. For example, company Z is in a process of

building organisational structures to enable better data collection, but is struggling with data collection processes

and resource constraints to support the necessary structure development and X is struggling with now inadequate

informal structures.

4.4. Performance measurement and integrating sustainability issues into decision-making

Most companies in our sample had adopted best practice approaches to integrating sustainability issues into decisionmaking using performance measurement techniques as a tool to encourage decision-making which considered social

and environmental impacts. A number of companies required a sign off that social and environmental impact had been

considered. As the environment director from company B (British utility) pointed out:

. . .to really integrate sustainable development into the business decision-making process means that you dont

have sustainable development people any more because everybody is in sustainable development. (Corporate

Environment Director, Company B).

The environment director of Company B (a British utility) described the recent changes brought about by adopting

a balanced scorecard approach:

. . .we could look at our Sales Director. . . you could say that his job has evolved from the dinosaurs. Ten years

ago it was about buying as much electricity as you could, as cheap as you could from generation, and selling

it to as many customers as you could. So his KPIs would quite clearly be profit margin, number of customers

gained, and a negative one, number of customers lost. And that is what his KPIs were like. That was the old

model. The new model is value added. He has got a couple of regulatory instruments to manage in terms of

delivering domestic energy efficiency commitments. He has got a certain amount of his energy to be supplied

from renewables or sources with Green certificates. So his new KPIs are going to be on his new scorecard. Its

going to be about cost effective delivery of reductions of CO2 and increasing the delivery of renewables. Its

going to be about cost effective delivery of his energy efficiency targets. It is more about a profit margin than

customer. It is going to be about customers retained which is going to be his customer care metric. So you can

see that between the two models, environment would have been an add-on in the old one, but it is at its core in

the new one. If I looked at the old one the way it was then, my KPIs would have been: How many bicycles did

you give them? How much waste paper did you use? (Corporate Environment Director, Company B)

Likewise, C (British utility) has moved away from assessing managers performance against financial KPIs and

adopted a companywide balanced scorecard which has sixteen measures on it, three of the four quadrants of which relate

to non-financial issues. Performance against these measures is linked to their remuneration. The company reinforces

its values through a monthly award scheme whereby for a particular value an employee is selected for demonstrating

that s/he is living that value in his or her daily work. There is also a set of business principles which set out behaviours

expected of staff. With regard to assessing projects, C used a formal evaluation process due to the high cost of submitting

bids. They claimed that they would not put a bid in for a project if they felt it was environmentally unsustainable even

if it made economic sense to do so.

At the time of our interview Company X (Australian bank) was just embarking on a balanced scorecard approach in

recognition of the need to develop of a more formalised management and measurement system to shift the organisation

296

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

from an informal focus on culture, to a formal KPI orientated means of management. As indicated, the previous

informal approach had relied on:

. . . the MD working himself to death getting in front of as many staff as possible, a very tight core of disciples

who understand the story and can do the same sort of thing. So a lot of face to face stuff, lot of travel. The classic

sort of things you do like the corporate videos you can send out to the staff and all the rest of it but as the staff

grows and spreads those things are less and less effective and thats where youve got to embed it into things

like a balance score card and measuring everything and reporting back and were in the very early stages of that

transitional process.

At the time of the interview, Australian bank X was coming to grips with what a balanced scorecard approach meant

for their organisation, what the potential relevant performance measures were, and how such measures should be used

throughout the organisation. There is still ongoing debate and concern about the change and the balance between

various areas of performance within the organisation, particularly as the advent of a more formal structure seems

counter to the existing reliance upon corporate culture.

Theyre the nominal numbers lets say. I dont know that theres going to be a hard and fast solution, because

weve struggled with it (BSC), to try as a tool to make it work for us. Like you need something and you recognise

that but is this just another means of constraining you in some way.

Formalisation of performance measures may lead to conflict with current ad hoc and diverse expectations of

performance as illustrated by this interviewee:

Its one of our national community banks conferences, there were some case studies presented by communities

whove done really well, paid out hundreds of thousands of dollars in community grants. At the lunch break one

of the directors from a very small town, 700 people in this case, came up to our MD and said . . . that was great,

. . . except that we regard our community bank as being a success because well break even. Weve secured a

banking service for our town of 700 people and that to us is equally as successful as communities handing out

hundreds of thousands of dollars. And that was a real reality check for us.

The interviewees expressed concerns that the formalisation of performance measurement detracted from the ability

to accept varying outcome levels, and of the diversity of community-based businesses currently undertaken by the

company. To facilitate the change, X (Australian bank) had made three senior HR appointments in the 6 weeks prior

to the interview to assist with the roll out of the balanced score card.

In company D (British utility), the Senior Environmental Advisor stressed that the KPIs included in the sustainability report did not exist in isolation, but were firmly integrated with sustainable development planning. One of her

performance objectives, for example, was to develop biodiversity action plans and strategies. Many of the indicators

reported by D are integrated into performance measurement criteria for individuals who have a specific responsibility

for the achievement of a target for a given criteria. However, businesses within the group adopt their own approaches

to this, some paying bonuses for achievement of particular objectives. HR has been receptive to a request that a community involvement element is included in each individuals personal appraisal to encourage staff to be aware of the

companys community policy and to consider community opportunities as part of their personal development.

The monthly environmental report to the Board is used in business planning in D, a process reinforced by the

Head of CSR speaking to all those developing business plans to ensure they incorporated the Sustainable Development plan. A risk assessment is conducted for all projects, responsibility for which lies at the business level whilst

responsibility for health and safety lies at the group level. There is an EMS and a formal process at group level for

incorporating environmental indicators into decision-making. Like many other high environmental impact companies,

the process is much more ad hoc for social indicators, the management of which is left to the businesses. The function

of utility D with the largest environmental impacts, service delivery, has identified a number of critical success factors

(CSFs), i.e.

. . .they are what the company has determined are critical to its success and that is why they are called critical

success factors. And there are a number of reasons. Some may be regulatory. Some are things on which we have

been monitored by economic regulators. Some are reputational. And there are workforce ones that go across a

range of environmental and social areas really, as well as economic. So these are critical areas for us.

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

297

Critical Success Factors include pollution incidents, leakage, water quality and sewer flooding. They are measured

monthly and incorporated into individual objectives continually reinforced and incorporated into business plans. The

impact of sustainability reporting and performance improvements on share price in D (British utility) was perhaps

particularly apparent because many of their environmental initiatives follow a court case as a consequence of environmental impacts. The (UK) public sector, which is an important customer of D, increasingly expected to demonstrate a

responsible attitude towards communities and the environment and thus gives social responsibility extra weighting in

the tender process. Interviewees felt that incorporating critical success factors into business planning made people in

D more aware of environmental impacts making consideration of them integral to the business and not just an add on.

Similarly, interviewees in company C emphasised the link between improvement in internal data collection and reporting systems and improved sustainability performance. They argued that a large volume of data used in decision-making

was reported internally only.

A key challenge for the Head of CSR at D was not in convincing directors of the benefits of social responsibility and

sustainability initiatives, but with regard to where the funding should come from. She said that there was a view within

the individual businesses that the group should pay for such initiatives on the grounds that the reputation gains were

to the group rather than the individual businesses. To circumvent this barrier, the CSR department will often facilitate

the development of initiatives and fund them in the first year with the businesses incorporating them into their budget

thereafter once the benefits are apparent.

At D work has also been undertaken with the Procurement Department to raise their awareness of environmental

and social impacts of procurement practices. Workshops held by D with their buyers revealed a diversity in buyers

knowledge of the environmental hazards and impacts of the products they were buying leading to the development

of guidance packs to assist buyers in identifying relevant questions to suppliers about the social and environmental

impacts of the product or service. More importantly perhaps, D held workshops with suppliers in an effort to assist

them in improving their environmental performance. Ds proactive approach is to be commended although the extent

to which it can actually lead to improved environmental performance in supplier organisations is unclear given that,

for the time being at least, D has committed to not dropping suppliers who do not answer questions on the social and

environmental impacts of their products and services satisfactorily. The new approach is however an improvement on

the previous approach where buyers simply asked suppliers if they had an environmental policy, D itself acknowledging

that the existence of a policy says nothing about the quality of environmental management.

Climate change and occupational, health and safety issues are embedded into the decision and performance assessment process of Y (Australian telecommunications). Climate change is seen as a risk to the organisation, hence from

a strategic perspective the cost of carbon emissions are considered when analysing any perspective investment, with

the financial analysis extended to include the potential cost of carbon. Occupational, health and safety targets are now

built into the employee share plan based on the organisation meeting specific targets. Specific aspects of social and

environmental performance are also built into the performance evaluation of the relevant managers, although the impact

may be limited since profit remains the predominant determinant of the bonus.

An issue of concern raised by company Y with respect to the use of data in decision-making was a lack of understanding as to what are appropriate benchmarks for performance. This concern also impacted upon external accountability,

with data collected on a number of issues not disclosed due to a fear that it may reflect badly on the organisation. For

example, with regard to gender equality, the interviewee indicated:

. . .for some reason, and were trying to understand this better, the call centres seem to attract more women and

secondly truck drivers and main laying gangs seem to be more men. I dont think theyre things that Company

Y does deliberately I think they are associated with the nature of the task . . .

The company has employed a consultant to investigate whether this bias is as a result of underlying issues within the

company, or an issue which the company has no control over. In the meantime it does not disclose gender information

by job type for fear that the failure to match national benchmarks could be used against them. The concern appears to

hinge around negative public relations and legal liability rather than a proactive stance on equal opportunities.

Company A (British Bank) uses four core competencies to assess the performance of individual staff, one of which

is Ethics in Action which measures an individuals performance against the organisations ethical values. The ethical

policy is translated into staff job descriptions. Each manager also has targets in his/her Individual Achievement Plan

related to the KPIs, although managers pay is linked to profit the reason given being that this in turn has been

found to be linked to customer satisfaction and the organisations ethical stance, with surveys showing that around

298

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

30% of customers are attracted by its ethical approach. With regard to the sustainability report, the Chief Executive,

Executive Directors and senior managers review it and provide feedback. The Chief Executives feedback is very

detailed with questions asked where results surprise him. Sustainability report KPIs are incorporated into action

plans.

Two key barriers to incorporating social and environmental considerations into decision-making were mentioned at A. They related to lack of knowledge and understanding. Firstly, some people incorrectly assume that

environmentally friendly options were also always more expensive. Secondly, the nature of the decision required

was sometimes misunderstood. For example, a buyer purchasing carpeting might assume that the important decision was about which carpet was more environmentally friendly, rather than about the environmental management

practices of the supplier. Suppliers and their products are screened for compliance with the Ethical Policy. At

the time the interviews were conducted company A was developing an Ecological Purchasing Manual to provide

guidance to staff on green suppliers. Thus, they are going somewhat further than utility D in specify preferred

suppliers.

Z (Australian forestry company) has collated data on social and environmental performance for a considerable

period of time, albeit on an ad hoc basis. The commitment to report externally and the subsequent requirement for

consistent, comparable data that could be verified was the catalyst for the development of performance measures. The

development of the performance measurement systems resulted in debate surrounding terminology, data collation and

the appropriate KPIs for this organisation. A new standardised data reporting framework at Z allows regional managers

to access additional data and to review their performance relative to previous years and other regions. As indicted by

an interviewee:

. . .previously people would give the data and it would disappear into head office and they would do this report

which was not useful . . . whereas now they can put the data in and sitting next to it is the data they put in last

year for their region. If they want to see the whole state they can but if they want to compare themselves to a

neighbouring region they can do that too, so it gives them that access to information.

The commitment to report and the sustainable reporting process has thus lead to the development of data collection

and performance management systems, in theory at least enabling managers to access greater levels of information

on comparative performance and better manage their own performance. However, the reality seemed to be that the

regional managers were somewhat remote from the process, with one interviewee remarking that, at the regional level

within the organisation . . . its seen more as a burden. This was further elaborated upon by an interviewee:

. . .in terms of the data, what is the burden is the data compilation I guess. Every, 30th June a memo goes out . . .

to regional managers saying the end of the financial year its time to start getting data together for the annual

report. . . .90 people in an organisation of 1100 stop what they were doing to do something to put into that report

and so in that way they see it as a burden. . .

Another interviewee clarified this by stating:

I think that its in some ways exacerbated by, the data being input at the regional level, collated and compiled

corporately and reported externally in that annual report. And their focus, the people who are gathering the data,

is very much operational and at the regional level it just by-passes their managers above them.

Complicating these issues further is the need for the organisation to generate a profit for the State Government

resulting in the economic indicators for the organisation being seen as the primary indicators when reporting to

Treasury:

. . . the Treasury have particular requirements in terms of financial components. We also have two and half million

hectares we currently manage, area that we can draw revenue from. . . You have to manage . . . On the whole

other values quite often get swamped in financial interests.

In all our sample organisations, some sort of performance measurement techniques, primarily the balanced scorecard

approach, were used to ensure that social and environmental impacts were considered in decision-making. In some

organisations the decision to report externally led to the greater availability of data which was an additional factor

influencing decision-making, whilst in others much of the data used in decision-making was internally reported only.

The process of reviewing data, including prior year comparative data and data disaggregated by business unit was

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

299

also an important factor influencing the decision-making process. The benefits of sustainability reporting and the

integration of sustainability issues into decision-making were seen to be: reputational benefits; impact of reputation on

share price; increase in staff pride in and loyalty to the company; competitive advantage in the (international) market

place; improved internal data collection and reporting systems; and, improved social and environmental performance.

Understanding of what sustainability means to the organisation and how the organisation engages its priorities

is also a key constraining factor for integration. The concept of sustainability engagement is certainly strong within

the case organisations, however the identification of what is important is rapidly evolving and hence not necessarily

consistently defined. Utility D has significant environmental impacts (many of which have regulatory implications) that

it has defined as critical success factors that are integrated within individual objectives, whereas Bank X (operating

in a relatively unregulated environment) is about to embark on a project to explore potential indicators. In each the

motivation to engage sustainability differed, and hence the timing and the process of identifying priorities varied. It

is the identification of these priorities which are seen as the key first step in the development of sustainable indicators

(Searcy et al., 2008), and therefore provides some insight into the variations observed based on the time frame in which

the organisation identified sustainability issues as significant.

5. Future directions

All of our sample companies had arrived at integrating sustainability issues into management processes for different

reasons and had gone about it in different ways. It was integrated into different aspects of management operations with

different emphasis in each organisation, and the aspects of sustainability which were important to each organisation

and their experience with the different dimensions of sustainability varied. No wonder then that their views on where

they should go in the future also varied. At the time of the interviews the finance department at D (British utility) had

started to investigate the possibility of introducing environmental accounting. In the future A (British Bank) wants

to do more work on ethical screening of the parent companies of suppliers and improve the way they measure what

they do in the community. On the role of companies in educating society, the Corporate Environment Director from B

(British Utility) said:

I think we have an educative role in terms of explaining the consequences of the use of our product, what kind

of things you can do to use it sensibly, but not the sort of societal shift which would move you towards a society

which is actually looking at consuming less. I dont mean just consuming less electricity but the whole gamut

of consumer society. You are talking about a different kind of economics there, and I think to ask an investor

owned utility to do that is difficult. It is the role of public education.

6. Conclusions

We found a considerable diversity across our sample in their approach to KPI selection, sustainability reporting,

sustainability reporting processes and their incorporation into aspects of decision-making impacting on sustainability

performance. There was some similarity in the issues of concern across organisations in the same sector. Four of the

seven companies studied were in high environmental impact organisations (the forestry and three utility companies)

and had a strong focus on environmental issues. However, there was considerable diversity in approach and breadth

of issues tackled, even between the two utility companies in the same country. The two banks rely on the corporate

social responsibility reputation to attract and retain customers and staff and, whilst this was a focus, their approaches

were different, one formal and one informal. To a lesser extent the telecommunications companys success is also

dependent on public perceptions of its role in society in an industry which is competitive with respect to corporate

social responsibility reputation. The diversity in approach reflects the fact that the sample companies came to managing

and reporting on their sustainability performance for a range of different reasons all primarily stemming from a business

case rather than a moral stance.

There were a number of indicators that the strength of the business case was perceived differently across the

organisations. Control of the sustainability reporting process rested with a diverse range of corporate functions, with

different core priorities: corporate affairs, corporate communications, corporate social responsibility or sustainability/environment personnel or a combination of these. The number of staff involved in the process, varied considerably.

Processes for developing KPIs varied from informal and ad hoc to highly formalised.

300

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

The issues companies faced in KPI development also varied including: adaptations for different geographical

regions and cultures; development of social and economic indicators, which lagged that for environmental indicators;

developing targets; benchmarking; and, comparability and consistency across reporting regions. The extent and means

by which KPIs were incorporated into decision-making and performance measurement also varied along with the

aspects of decision-making that were being emphasised.

Whilst pressures to produce a sustainability report were not the key driver to address corporate social responsibility

issues for all of the companies, the process of developing KPIs for the purposes of sustainability reporting has focussed

attention on social and environmental performance. The desire to report data externally has led to developments in

data collection systems and the integration of social and environmental performance data into decision-making, risk

management and performance measurement. It was not the purpose of this study to review performance to determine

the extent to which it had changed, but to examine how social and environmental information is used in decision-making

and performance management.

As with external sustainability reporting, internal systems may be at different stages of development. Industries

traditionally associated with adverse environmental impact have extended histories in reporting environmental information (Guthrie & Parker, 1989) and also in the development of guidelines to assist environmental management. The

external operating environment has provided considerable explanatory power as to variations in this level of response.

There is however evidence of internal factors that may drive the initiation of sustainability management and provide

insights into variations in the extent to which organisations integrate on sustainability issues into their business (see

also Adams, 2002).

The diversity of approaches found in this study is reflective of organisations realising a growing need to engage

with sustainability issues, but without some common point of reference in terms of issues to be managed or a common

development framework. What is clear is that the development of integrated sustainability reporting and management

is not green field, it is influenced and constrained by existing processes, indeed for a number of the case organisations

development is contained within existing processes. The question may then relate to the capacity of organisations, or

their ability to build capacity, to develop integrated systems.

The study also highlights a profusion of alternate triggers for prioritising sustainability, from regulatory requirements,

improved external reporting processes to embedding an existing culture. The study has captured organisations, not

only with different processes but also at different stages of development of integrated sustainability performance

management. Whilst there have been prior attempts at modelling different stages of development within organisations

with respect to external reporting and engagement (e.g. Elkington, 1993), they have provided limited insight into the

stages in the development of integrated sustainability management and reporting.

Our data provides some evidence that accountability to stakeholders is compromised where it was perceived that data did not reflect positively on the organisation. This, and the self-interest apparent from the

concern for the business case, indicates that governments need to find means of encouraging greater accountability. Despite being driven by the business case rather than a concern with accountability to stakeholders,

our research points to a link between sustainability reporting and organisational change aimed at improving sustainability performance for our sample organisations. This suggests that a focus by governments on

improving accountability would result in changes being implemented which could lead to improved performance.

Our research adds to our knowledge of the extent and manner in which social and environmental data is used in

decision-making. Due to the exploratory and qualitative nature of our study our sample was limited and further research

is required to examine these links and employ theoretical perspectives to explain these links, the change process and

the impact on performance. Particular attention might be paid to the location and reach of the sustainability reporting

function within the organisation and the degree of formality versus informality in the data collection, reporting and

performance management processes. This might be done through an in depth action research approach (see Adams &

McNicholas, 2007) or an ethnographic approach (see Dey, 2007) using elements of institutional and/or organisational

theory (see Adams & Larrinaga Gonzalez, 2007).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for funding received from the UK Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA)

and the companies who agreed to be interviewed for this project. They would also like to acknowledge comments

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

301

received from Graeme Dean and Lee Parker on the initial research proposal, comments from Jane Baxter on an earlier

draft of the paper and research assistant support provided by Greg Tangey.

References

Adams, C. A. (2002). Factors influencing corporate social and ethical reporting: Moving on from extant theories. Accounting, Auditing and

Accountability Journal, 15(2), 223250.

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environmental reportingPerformance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal,

17(5), 731757.

Adams, C. A., & Larrinaga Gonzalez, C. (2007). Engaging with organisations in pursuit of improved social and environmental accountability and

performance. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(3), 333355.

Adams, C. A., & McNicholas, P. (2007). Making a difference: Sustainability reporting, accountability and organisational change. Accounting,

Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(3), 382402.

Adams, C., & Harte, G. (1998). The changing portrayal of the employment of women in British banks and retail companies corporate annual

reports. Accounting, Organization and Society, 23(8), 781812.

Albelda-Perez, E., Correa-Ruz, C., & Carrasco-Fenech, F. (2007). Environmental management systems and management accounting practices as

engagement tools for Spanish companies. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(3), 403422.

Belal, A. R., & Owen, D. L. (2007). The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh:

An engagement case study. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(3), 472494.

Bennett, M., & James, P. (1998a). The Green Bottom Line. In M. Bennett & P. James (Eds.), The Green Bottom Line: Environmental Accounting

for Management Current Practices and Future Trends. Greenleaf Publishing.

Bennett, M., & James, P. (1998b). Making environmental management count: Baxter internationals environmental financial statement. In M.

Bennett & P. James (Eds.), The Green Bottom Line: Environmental Accounting for Management Current Practices and Future Trends. Greenleaf

Publishing.

Business in the Community (2000). Winning with Integrity. Business in the Community. (Available at www.bitc.org.uk/resources/publications/

winning.html).

Business in the Community (2004). Corporate Responsibility Index. Business in the Community. (Available at www.bitc.org.uk/crindex).

Chenhall, R. H. (2005). Integrative strategic performance measurement systems, strategic alignment of manufacturing, learning and strategic

outcomes: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30, 395422.

Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2003). Performance measurement and reward systems, trust, and strategic change. Journal of Management

Accounting Research, 15, 117144.

Cooper, S. M., & Owen, D. L. (2007). Corporate social reporting and stakeholder accountability: The missing link. Accounting, Organisations and

Society, 32, 649667.

Delmas, M., & Toffel, M. (2004). Stakeholders and Environmental Management Practices: An Institutional Framework. Business Strategy and the

Environment, 13, 209222.

Dey, C. (2007). Social accounting at Traidcraft Plc: A struggle for the meaning of fair trade. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3),

423445.

Dias-Sadinha, I., & Reijnders, L. (2001). Environmental performance evaluation or organizations: An evolutionary framework. Eco-Management

and Auditing, 8, 7179.

Ditz, D., Ranganathan, J., & Banks, R. D. (Eds.). (1995). Green Ledgers: Case Studies in Corporate Environmental Accounting. Washington: World

Resources Institute.

Elkington, J. (1993). Coming clean: The rise and rise of the corporate environmental report. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2, 421744.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Oxford: Capstone.

Epstein, M. J. (1996). Measuring corporate environmental performance. Chicago: Irwin.

Frost, G. R., & Wilmshurst, T. D. (2000). The adoption of environment-related management accounting: An analysis of corporate environmental

sensitivity. Accounting Forum, 24(4), 344365.

Global Reporting Initiative (2000). Global Reporting Guidelines on Economics, Environmental, and Social Performance. http://www.

globalreporting.org/GRIGuidelines/June2000/June2000Guidelines8X11.pdf.

Global Reporting Initiative (2006). G3. http://www.globalreporting.org/ReportingFramework/G3Online/ (accessed January 29, 2007).

Guthrie, J., & Parker, L. D. (1989). Corporate social reporting: A rebuttal of legitimacy theory. Accounting and Business Research, 9, 343352.

Harris, N. (2007). Corporate engagement in processes for planetary sustainability: Understanding corporate capacity in the non-renewable resource

extractive sector, Australia. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16, 538553.

ISEA. (1999a). Accountability 1000 (AA1000): A foundation standard in social and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting. London: ISEA.

ISEA. (1999b). Accountability 1000 (AA1000) Framework: Standard, guidelines and professional qualication. London: ISEA.

Ittner, C. D., Lackner, D. F., & Randall, T. (2003). Performance implications of strategic performance measurement in financial services firms.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, 715741.

Johnston, A., & Smith, A. (2001). The characteristics and features of corporate environmental performance indicatorsA case study of the water

industry of England and Wales. Eco-Management and Auditing, 8, 111.

Kaplan, R., & Cooper, R. (1998). Cost and effect, using integrated cost systems to drive protability and performance. Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

Koehler, D. A. (2001). Developments in health and safety accounting at Baxter International. Eco-Management and Auditing, 8, 229239.

302

C.A. Adams, G.R. Frost / Accounting Forum 32 (2008) 288302

Kolk, A., & Mauser, A. (2002). The evolution of environmental management: From stage models to performance evaluation. Business Strategy and

the Environment, 1, 1431.

ODwyer, B. (2002). Managerial perceptions of corporate social disclosure: An Irish story. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15,

406436.

ODwyer, B. (2003). Conceptions of corporate social responsibility: The nature of managerial capture. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability

Journal, 16, 523557.

Parker, L. D. (2000). Green strategy costing: Early days. Australian Accounting Review, 10(1), 4655.

Parker, L. D. (2005). Social and environmental accountability Research: A view from the Commentary Box. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability

Journal, 18(6), 842860.

Schaltegger, S., & Burritt, R. L. (2000). Contemporary environmental accountingissues, concepts and Practice. Sheffield: Greenleaf publishing.

Searcy, C., McCartney, D., & Karapetrovic, S. (2008). Identifying priorities for action in corporate sustainable development indicator programs.

Business Strategy and the Environment, 17, 137148.

You might also like

- Developing Your Own Case StudyDocument33 pagesDeveloping Your Own Case StudyNero ShaNo ratings yet

- ICS Case Study (Ethical Dilemma)Document1 pageICS Case Study (Ethical Dilemma)Nero ShaNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 (PMS 1)Document41 pagesTopic 6 (PMS 1)Nero ShaNo ratings yet

- Com Law Question 4Document2 pagesCom Law Question 4Nero ShaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Vision and Mission AnalysisDocument40 pagesChapter 5 - Vision and Mission AnalysisNero Sha100% (5)

- Walt Disney Strategic CaseDocument28 pagesWalt Disney Strategic CaseArleneCastroNo ratings yet

- Capital Allowances: Zulkhairi@um - Edu. MyDocument35 pagesCapital Allowances: Zulkhairi@um - Edu. MyNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Performance Measurement SystemsDocument36 pagesContemporary Performance Measurement SystemsNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Personality ValuesDocument32 pagesChapter 5 - Personality ValuesNero ShaNo ratings yet

- 3229 - Lecture 14 - Development in PSADocument10 pages3229 - Lecture 14 - Development in PSANero ShaNo ratings yet

- Project Planning ProcessDocument23 pagesProject Planning ProcessNero ShaNo ratings yet

- ch17 SDocument30 pagesch17 SNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 12 - Working Capital and Current Assets ManagementDocument76 pagesLecture 12 - Working Capital and Current Assets ManagementNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Lec14 ShariahDocument21 pagesLec14 ShariahNero ShaNo ratings yet

- The Source of Malaysian LawDocument2 pagesThe Source of Malaysian LawNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Hindu Scientific FactsDocument1 pageHindu Scientific FactsNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Applicationform Undergrad 2014Document4 pagesApplicationform Undergrad 2014Nero ShaNo ratings yet

- Study Link Personal StatementDocument9 pagesStudy Link Personal StatementNero ShaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- SSRN Id4380365Document30 pagesSSRN Id4380365Lucas ParisiNo ratings yet