Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A New Model of Professionalization of Teachers in Pre-School and Primary School Education

Uploaded by

muhammad choerul umamOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A New Model of Professionalization of Teachers in Pre-School and Primary School Education

Uploaded by

muhammad choerul umamCopyright:

Available Formats

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

ScienceDirect

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

The 6th International Conference Edu World 2014 Education Facing Contemporary World

Issues, 7th - 9th November 2014

A New Model of Professionalization of Teachers in Pre-school and

Primary School Education

Iuliana LUNGU*

Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Ovidius University of Constana, 124 Mamaia Blvd, Constana 900527, Romania

Abstract

The central idea of the paper refers to the need to create and implement a new model of professionalization for pre-school and

primary school teachers who will be proficient in English language skills, ensuring the quality of teaching early English language

and therefore determining its status in kindergarten and primary school as compulsory subject. From this perspective, the

investigative approach of this study is on teaching English to young learner (TEYL) new policy and practice at the European

level, the Romanian context and how the process of teaching-learning is perceived by the trainee teachers preparing for Preschool

and Primary education at our University. The paper will also serve to shape the new identity of this kind of teacher proficient in

English, as representing a fundamental criterion in designing new educational curriculum for linguistic educators in Romanian

education.

Published byby

Elsevier

Ltd.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

2015

2015The

TheAuthors.

Authors.Published

Elsevier

Ltd.

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Peer-review under responsibility of The Association Education for tomorrow / [Asociatia Educatiepentrumaine].

Peer-review under responsibility of The Association Education for tomorrow / [Asociatia Educatie pentru maine].

Keywords:: Romanian preschool and primary school teachers; English language skills; teaching early English language;

1. Introduction

The central idea of the paper is the need to create and implement a new model of professionalization of English

language skills for Romanian preschool and primary school teachers, ensuring the quality of teaching English

language and directly determining the status of compulsory subject for this language studied in kindergarten and

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: iulianalungu@yahoo.com

1877-0428 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Peer-review under responsibility of The Association Education for tomorrow / [Asociatia Educatie pentru maine].

doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.171

Iuliana Lungu / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

633

primary school. From this perspective, the goal of research is promoting the idea of qualification and specific

training of teachers in Romanian preschool and primary education to be proficient in English and formulating

directions for future primary education curriculum development, in accordance with the standards of this new

professional competence. This is not possible without having a clear idea of the impact of global processes on

teaching English to young learner (TEYL) policy and practice, the Romanian context and its formal school language

learning, how the process of teaching-learning languages is perceived by in-service preschool and primary teachers

and trainee teachers and how local solutions may resonate globally and efficiently.

English is increasingly seen a generic skill, according to Graddol (2008:12), leading governments and

educational policy developers to lower the starting age with the aim of building strong English proficiency levels for

an English-speaking workforce. As a result, the widespread introduction of English in primary schools or even

earlier (the earlier, the better assumption behind) has been described by Johnstone (2009:33) as possibly the

worlds biggest policy development in education. This has an impact on pre-primary and primary education, as

illustrated in the latest TEYL Primary Curriculum which represents a significant shift towards more learner-centred

approaches, learner autonomy and communicational skills.

Countries respond differently to the challenge of improving English language proficiency in schools. In Europe,

the prevailing trend has been to introduce mandatory programmes from 6-7 years, e.g. Poland is introducing an

official start from Grade 1; Croatia introduced an official start from Grade 1 in 2003, Hungary likewise, this trend

being promoted by a strong recommendation from the EU policy group that the first language should be

introduced from the early primary or pre-school phase. In short, the impact of the global processes has introduced a

real challenge to the process of policy implementation and implicit in introducing English learning across a whole

state system from an early age. The familiar themes arisen in many countries are those related to the optimal start

age, teacher quality and level of English proficiency, classroom context, materials and resources, curriculum and

assessment design, equity of provision and so on.

The major trends and issues in the teaching of English to primary school aged children in the 21st century seem

to be the following:

1) A continuing enthusiasm for reducing the age at which the teaching of English begins.

Research does not support the view that the age of the learner is the paramount condition affecting successful

language learning. It is not the case that in the absence of proper conditions for learning, such as adequate exposure

to and engaging interaction in the language, younger is better. In spite of this, in many contexts a trend towards

reducing the age at which English is introduced can be traced through this survey and it is particularly notable that

English teaching is now widespread at pre-school Early Years levels. The introduction of English at ever-younger

ages is not in itself problematic but it can become so when it is not matched by the material and teacher education

resources needed to ensure that the appropriate conditions for learning are in place. As this survey has shown, the

reality is that resources in many contexts are either lacking or not forthcoming to the extent needed.

2) Continued pressure on teacher supply and teacher quality

Compromises still seem to be being made over actual as opposed to ideal or statutory qualifications for teachers

of English at primary school as expansion of English teaching creates more demand for personnel at this level. The

large number of responses to the questionnaire claiming considerable high level policy support for EYL teaching

as opposed to rather fewer claiming on the ground financial, resource and training support points to a frequently

found weakness in educational systems worldwide. There were numerous comments about difficulties in preparing

and supplying an adequate number of suitable teachers for the task of teaching primary school English and these

difficulties could be seen at least partly as a consequence of a failure to back policy with resources.

3) Increased awareness of, and attention to, assessment issues, including the setting of target levels

2. Research hypothesis

2.1. What is wrong with approaches to teaching English to young learners today?

Nunan (2008) notices there are several factors that need to be taken into consideration when designing curricula

and teaching materials.

634

Iuliana Lungu / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

1. Curriculum models should be developmentally appropriate to the age and stage of the learner. All too often,

models developed for high school students or even adults are imported into the primary classroom.

2. Methodology needs to be age appropriate. It is as inappropriate to give young learners formal grammar lessons

as it is to ask adults to learn a foreign language by manipulating glove puppets.

3. Teachers must be trained to teach languages to young learners. Very often foreign language teachers in

primary schools have no training in the teaching of language to young learners. They should be specially trained to

work with children.

4. Intensive English language teaching in the first few grades (e.g. five class hours per week). Intensity of

instruction must be sufficient.

2.2. Global vs. Local - The Romanian context

In 2012 the British Council facilitated a worldwide survey of policy and practice in the teaching of English as a

foreign or second language to young learners (defined as children of primary school age, roughly between the ages

of 5 and 12). The purpose of the survey was to gain as complete as possible a view of the organisational frameworks

that support young learners teaching worldwide and of the policies and other administrative decisions that lie

behind them.

The data collected were taken from 64 countries, including Romania, and consisted of a detailed questionnaire

completed on paper or via email by a known Young Learner expert in each country or region.

The subsequent report highlighted themes within the questionnaire, starting with policy and facts and figures

concerning institutions and personnel, and moving to more specifically professional and pedagogical topics such as

the curriculum and teaching materials, targets for attainment in English and the ways in which transition from

primary to secondary school is managed.

It was decided for the survey to ask also about provision for English in the years before the official start of

primary school, variously known as pre-school, kindergarten or nursery education. This was in order to investigate

whether the continued lowering of the age at which English was started in primary school in many contexts might

have carried through into formal or informal introduction of English at still younger ages. The report pointed out the

fact that in Romania, the practice of parents paying extra for English lessons seems widespread in both state and

private kindergartens:

Comment:

Most of the children in (state) kindergarten learn English because parents pay a private teacher. The classes are

optional, but all parents are willing to make sure the kids are exposed to English at an early stage in kindergarten. In

private kindergartens, English classes are provided as part of the compulsory curriculum. There are some private

schools where children speak only English during all programs, classes, activities.

The teaching of English in Early Years education may cause problems of coherence in the teaching of English at

a later stage, as this comment from the Romanian experts response to Question 7 in the questionnaire (To your

knowledge, have there been any major policy changes in the last ten years, for example with regard to the status of

English in primary schools, the required level of English language proficiency to be reached, assessment, or with

regard to the age of starting English?) underlines:

Comment:

Studying English has become essential in primary school in Romania in the last ten years. However, there is a

total lack of coherence as far as childrens linguistic level is concerned because when they register at Grade 1,

students come from different kindergartens (some with good knowledge of English, some with no experience in

learning English).

From the above data it would seem that the hypothesis that enthusiasm for English learning is frequently

cascading into Early Years teaching has ample evidence to support it.

Other central issues for a worldwide survey are the decisions made about which categories of teachers may be

employed in the important work of laying the foundations of most childrens English and whether human resources

are sufficient to carry forward the high ambitions that we have already seen in this report. Teacher supply and

quality are thus the main themes explored here in detail.

Iuliana Lungu / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

635

Sufficient numbers of English teachers?

Comment:

It is impossible to calculate number of teachers! The teachers of English quit the job in a school after one to two

years, some are not actually teachers of English but they teach English if the full-time teacher in the school is on

maternity/medical/study leave; some teachers are employed in one school, but they collaborate with other schools

too and if someone wants to count, they will appear twice or three times in statistics. However, the average is one to

two teachers of English in a general school, i.e. 4,700 9,400 teachers; but it is just a very vague calculation. In the

provinces the teachers of English for primary schools are actually teachers of general education for Grades 1 4 with

some knowledge of/education in English language.

An important factor in implementing the teaching of English is the amount of guidance and support that teachers

receive through syllabus and other documentation.

Official documents for teachers on content:

Comment:

There are general curricula and detailed syllabuses available which are mandatory according to the Ministry of

Education. Based on these two documents, each teacher should write a very detailed plan, which should include all

lesson plans for the entire year at the beginning of the year. Although this stage is mandatory, many teachers start

the year without the plans and some finish the year without plans. Most of them write the detailed plans at the

beginning of the years when they have graduation exams, i.e. after two years of teaching. There is one exam called

definitivat which makes the teacher a sort of qualified teacher for life in the Romanian system (you can get your

definitivat in French or even chemistry, but be considered a teacher for life in the Romanian system even if you

want to teach drawing), Grade 1 after four years; not mandatory, Grade 2 after six years; not mandatory. However, a

teacher cannot get Grade 2 if he/she hasnt got definitivat and Grade 1 previously.

This survey conducted by the British Council reveals a situation in which some aspects of English teaching to

children have developed in a generally positive direction in many contexts since the last British Council survey in

1999 2000, although a number of serious problems remain to be solved. On the positive side, there is increased

interest at a policy level in defining and setting goals for primary English and the CEFR (Common European

Framework of Reference) seems to have been helpful in setting this in motion. However, we have seen that the

CEFR is not itself an instrument designed to describe the language performance of children and that modifications

will be needed if it is to be fully useful. An additional point is that the assessment of childrens language attainments

is still a developing field, although work such as that done within the ELLiE project (Enever, 2011) has added much

to our understanding. Often it seems that appropriate means of verifying if primary school children actually reach

the goals stated in policy documents are yet to be put in place. A related problematic area is that coherence between

primary and secondary school English language programmes remains a problem in many parts of the world. The

biggest issues, however, continue to revolve around the resources, both human and material, that need to be

deployed in the classroom and the appropriate means of orienting and training teachers for their tasks. An important

difference from the time of the first survey is that in 1999 2000 the issues in many contexts revolved around

appropriate approaches with children from eight years upwards but with the trend for an ever earlier start the focus

is likely to be in future years not only on the first years of primary education but on what can be achieved at preschool level and how to ensure continuity and coherence thereafter. It seems that a very considerable amount is

being demanded of teachers who have been caught up with the continuing enthusiasm for

2. Methodology and findings

This study was carried out by survey method. Based on a questionnaire applied to 45 students at university

preparing to become preschool and primary school teachers (irrespective of their proficiency in English and with no

English teaching methodology input) during the second semester of the academic year 2013-2014. The main aim of

the survey was to examine the trainee teachers opinions, beliefs and perceptions on the new model of

professionalization for this kind of teacher, i.e. Romanian preschool and primary school teacher having English

language skills. The questionnaire (reactionnaire) was used as a measure of their immediate reactions to the

questions below (the most basic level of impact).

636

Iuliana Lungu / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

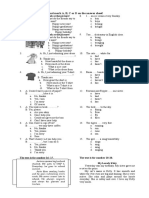

As can be seen from Figure 1, most participants (over 90%) believe that it is necessary to have preschool/primary

school teachers with English language skills even if their responses varied slightly (24% of the respondents consider

that it is very important, 31% report that it is important while 44% are less enthusiast about this condition).

Question 1: To what extent do you think it is necessary that the

preschool/primary school teachers should have English

language skills?

4%

2%

24%

a) to a very great extent

b) to a great extent

c ) to a moderate extent

d) to a s mall extent

44%

e) to a very s mall extent

31%

Figure 1

The data presented in Figure 2 reveal 75% of respondents as being in favour of the idea that the preschool teacher

/ primary school teacher can use these language skills even within classes of English language (15% very much

agree, 33% much agree and 27% reasonably agree).

Question 2: Do you agree that the preschool/primary school

teachers can use these language skills even within classes of

English language?

9%

15,50%

13%

a) s trongly agree

b) agree

c ) neutral

d) dis agree

33%

27%

e) s trongly dis agree

Figure 2

As is clear from Figure 3, 84% of the participants respond positively and consider the English language training

programme as beneficial even if only half of them are more interested in it.

Iuliana Lungu / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

637

Question 3: To what extent do you think it is beneficial that

preschool/primary school teachers should be trained and

qualified as teachers of English as well in the Romanian

preschool/primary school education?

18%

0%

15%

a) to a very great extent

b) to a great extent

c ) to a moderate extent

d) to a s mall extent

29%

40%

e) to a very s mall extent

Figure 3

As for the question 4 Which would be the main advantage that you can identify in case the pre-school teacher /

primary school teacher with language skills is responsible for the English language classes?, the most relevant and

mentioned advantage is the fact that the teacher in debate is already trained to work with children as a result of

his/her background education and qualification and it is much easier to qualify him/her to teach English and in this

way to have an overall teacher quality appropriate for teaching younger children.

Question 5 asks participants to refer to the main disadvantage, Which would be the main disadvantage that you

can identify in case the pre-school teacher / primary school teacher with language skills is responsible for the

English language classes?, and most answers revolve around the same issue, the lack of linguistic self-confidence

of the preschool/primary school teacher, predicated on the belief that a specialised English teacher competence

would be much required to teach English successfully to younger children.

3. Discussions

We have found this investigative study rewarding in both practical and research terms. In terms of the pedagogy

of teacher education, the study uncovered significant factors concerning the teaching English to young learners

globally through the different surveys conducted by British Council, the most significant is ELLiE report (2012)

mentioned above in this paper. Locally, the paper presented the perspective of the Romanian trainee teachers who

have no language methodology input but it would be interesting to continue this study and to see what beliefs and

perceptions these trainee teachers would have after implementing the training programme at the start of the third

year methodology course.

4. Conclusions

This study opens the door to creating and implementing the Primary English training progamme for the trainees

at the start of the third year methodology course based on some major recommendations such as:

1. training programme should be of short duration and focused, more precisely it should focus on aspects of

language teaching for young learners that are highlighted as important by teachers and on effective strategies

reported in the research literature on young learners;

2. education policy developers should be provided with evidence based on current research and good practice in

effective curriculum development for young learners in order to enhance the learning experience of children;

3. promoting further research on the specific needs of teachers of young learners in relation to English language

development.

638

Iuliana Lungu / Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 180 (2015) 632 638

References

ELLiE Early Language Learning in Europe, British Council.(2011). The ELLiE research project was supported by a European Commission

grant under the Lifelong Learning Programme, Project number 135632-LLP-2007-UK-KA1SCR.

Enever, J., and Moon, J. (2009). New global contexts for teaching Primary ELT: change and challenge. In J. Enever, J. Moon and U. Raman

(Eds.), Young Learner English Language Policy and Implementation: International Perspectives (pp. 521). Reading: Garnet Education.

Graddol, D. (2008). How TEYL is changing the world. Paper presented at the Bangalore conference, The way forward: learning from

international experience of TEYL, 36 January, 2008. RIESI: Bangalore, India.

Johnstone, R. (2009). An early start: What are the key conditions for generalized success? In J. Enever, J. Moon and U. Raman (Eds.), Young

Learner English Language Policy and Implementation: International Perspectives (pp. 3141). Reading: Garnet Education.

Nunan, David. (2012). What is wrong with approaches to teaching English to young learners today?. Webinar published in 2012 on

http://www.pearsonlongman.com.

You might also like

- UTS - Eni Uli Nimah (K7519022)Document6 pagesUTS - Eni Uli Nimah (K7519022)muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Motorola Corp.: Ir. Soekarno Street, 17B JakartaDocument7 pagesMotorola Corp.: Ir. Soekarno Street, 17B Jakartamuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Akhh Lawyer: Subject: Defendant Answer IiDocument26 pagesAkhh Lawyer: Subject: Defendant Answer Iimuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Learning Application For Basic Router and Switch Configuration On Android PlatformDocument10 pagesMobile Learning Application For Basic Router and Switch Configuration On Android Platformmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- ACME PresentationDocument6 pagesACME Presentationrockincathy17No ratings yet

- Developing of MLearning For Discrete Mathematics Based On Android PlatformDocument4 pagesDeveloping of MLearning For Discrete Mathematics Based On Android Platformmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- The Cover LetterDocument5 pagesThe Cover LetterZain UlabideenNo ratings yet

- Subject: Exception and Defendant's Answer V Attachment: Power of AttorneyDocument6 pagesSubject: Exception and Defendant's Answer V Attachment: Power of Attorneymuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Ex of Cover LetterDocument2 pagesEx of Cover Lettermuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- CV Examples: How to Highlight Skills & AchievementsDocument8 pagesCV Examples: How to Highlight Skills & AchievementsCrye BiggieNo ratings yet

- 2013 (4 1-30)Document9 pages2013 (4 1-30)muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Для просмотра статьи разгадайте капчу PDFDocument38 pagesДля просмотра статьи разгадайте капчу PDFmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- January 2016 Attendance and PayrollDocument2 pagesJanuary 2016 Attendance and Payrollmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- IFOTS v9 n2 Art2Document16 pagesIFOTS v9 n2 Art2muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- (Perkembangan Bahasa) : (Nilai)Document1 page(Perkembangan Bahasa) : (Nilai)muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Daily Test I: Complete The Dialogues Below With The Suitable Expressions Inthebox!Document2 pagesDaily Test I: Complete The Dialogues Below With The Suitable Expressions Inthebox!muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Student Profile TemplateDocument1 pageStudent Profile Templatemuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- I. Choose The Best Answer and Mark A, B, C or D On The Answer Sheet!Document2 pagesI. Choose The Best Answer and Mark A, B, C or D On The Answer Sheet!muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan SEPARODocument4 pagesPerhitungan SEPAROmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan May 2016Document4 pagesPerhitungan May 2016muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan 2016hDocument2 pagesPerhitungan 2016hmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Daily Test I: Complete The Dialogues Below With The Suitable Expressions Inthebox!Document2 pagesDaily Test I: Complete The Dialogues Below With The Suitable Expressions Inthebox!muhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- TK Umum dan Nasrani Doa Pembuka dan PenutupDocument2 pagesTK Umum dan Nasrani Doa Pembuka dan Penutupmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument13 pages1 PB PDFmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Attitudes and ApplicationsDocument5 pagesAttitudes and Applicationsmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- School Aged Children and Adult Language Production in An Indonesian TV ShowDocument23 pagesSchool Aged Children and Adult Language Production in An Indonesian TV Showmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument13 pages1 PB PDFmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Donasi Solo OrganDocument2 pagesDonasi Solo Organmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- Ecc Al AzharDocument1 pageEcc Al Azharmuhammad choerul umamNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Reflection About Threats To Biodiversity and Thought Piece About Extreme MeasuresDocument2 pagesReflection About Threats To Biodiversity and Thought Piece About Extreme MeasuresNiña Dae GambanNo ratings yet

- Public Perception of Radio Nigeria ProgrammeDocument9 pagesPublic Perception of Radio Nigeria Programmeruthbunmi84No ratings yet

- Comm 170 SyllabusDocument7 pagesComm 170 SyllabushayleyNo ratings yet

- Workshop Session I: Public Expenditure Financial Accountability (PEFA) AssessmentDocument29 pagesWorkshop Session I: Public Expenditure Financial Accountability (PEFA) AssessmentInternational Consortium on Governmental Financial ManagementNo ratings yet

- Exercise 13.1 Page No: 157: NCERT Exemplar Solutions For Class 10 Maths Chapter 13-Statistics and ProbabilityDocument19 pagesExercise 13.1 Page No: 157: NCERT Exemplar Solutions For Class 10 Maths Chapter 13-Statistics and ProbabilitySaryajitNo ratings yet

- Abertay Coursework ExtensionDocument4 pagesAbertay Coursework Extensiondut0s0hitan3100% (2)

- 05 N269 31604Document23 pages05 N269 31604Antony John Britto100% (2)

- Regional Dairy Farm BenchmarkingDocument28 pagesRegional Dairy Farm BenchmarkingMadhav SorenNo ratings yet

- Studying in Finland GuideDocument4 pagesStudying in Finland GuideMohsin FaridNo ratings yet

- T309 - Microbiological Quality Control Requirements in An ISO 17025 Laboratory PDFDocument26 pagesT309 - Microbiological Quality Control Requirements in An ISO 17025 Laboratory PDFПламен ЛеновNo ratings yet

- Allen Forte - Context and Continuity in An Atonal WorkDocument12 pagesAllen Forte - Context and Continuity in An Atonal WorkDas Klavier100% (1)

- 2019 Project PreventDocument93 pages2019 Project PreventTim BrownNo ratings yet

- What Do We Really Know About Entrepreneurs? An Analysis of Nascent Entrepreneurs in IndianaDocument22 pagesWhat Do We Really Know About Entrepreneurs? An Analysis of Nascent Entrepreneurs in IndianaSơn Huy CaoNo ratings yet

- Botox Research PaperDocument9 pagesBotox Research PaperMarinaNo ratings yet

- Marketing ProjectDocument68 pagesMarketing Projectdivya0% (1)

- Summative Entrep Q3Document2 pagesSummative Entrep Q3Katherine BaduriaNo ratings yet

- Seismic Refraction Study Investigating The Subsurface Geology at Houghall Grange, Durham, Northern EnglandDocument7 pagesSeismic Refraction Study Investigating The Subsurface Geology at Houghall Grange, Durham, Northern EnglandCharlie Kenzie100% (1)

- Research Methods Are of Utmost Importance in Research ProcessDocument6 pagesResearch Methods Are of Utmost Importance in Research ProcessAnand RathiNo ratings yet

- SotDocument74 pagesSotvinna naralitaNo ratings yet

- SP40 - Steel Potral Frames PDFDocument135 pagesSP40 - Steel Potral Frames PDFAnkur Jain100% (2)

- Human Resources at The AES CorpDocument3 pagesHuman Resources at The AES Corpeko.rakhmat100% (1)

- Sports Betting Literature ReviewDocument29 pagesSports Betting Literature ReviewSeven StreamsNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues Revenue Management PDFDocument2 pagesEthical Issues Revenue Management PDFTylerNo ratings yet

- ATP 1: Social Psychology 1: The Nature of Social PsychologyDocument24 pagesATP 1: Social Psychology 1: The Nature of Social Psychologypallavi082100% (1)

- Thesis Guideline For MD (Pathology) : Published or Unpublished)Document4 pagesThesis Guideline For MD (Pathology) : Published or Unpublished)Mohd. Anisul IslamNo ratings yet

- Title of Project: Box 16. GAD Checklist For Project Management and ImplementationDocument7 pagesTitle of Project: Box 16. GAD Checklist For Project Management and ImplementationArniel Fred Tormis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Submitted As Partial Fulfillment of Systemic Functional Linguistic Class AssignmentsDocument28 pagesSubmitted As Partial Fulfillment of Systemic Functional Linguistic Class AssignmentsBhonechell GhokillNo ratings yet

- Marketing Research and Sales Distribution of Haldiram SnacksDocument66 pagesMarketing Research and Sales Distribution of Haldiram SnacksAJAYNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Stylistics and Discourse AnalysisDocument12 pagesIntroduction to Stylistics and Discourse AnalysisElaine Mandia100% (1)

- Statistics Week 1Document3 pagesStatistics Week 1Jean MalacasNo ratings yet