Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Establishment Firm or Enterprise

Uploaded by

TBP_Think_TankCopyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEstablishment Firm or Enterprise

Uploaded by

TBP_Think_TankNovember 2016

Establishment, firm, or enterprise: does the unit

of analysis matter?

Job flows at the establishment and firm level are a

powerful tool for understanding employment dynamics.

The information at each of those levels is robust,

accurate, and timely. In addition, quarterly and annual

BLS Business Employment Dynamics data show that

enterprise- and firm-level series consistently track each

other and follow a similar pattern of peaks and troughs

over the business cycle.

Economic data for businesses are usually constructed at

the establishment level, the firm level, or the enterprise

level. An establishment is a single physical location where

one predominant activity occurs. A firm is an

establishment or a combination of establishments and, for

Akbar Sadeghi

sadeghi.akbar@bls.gov

the purposes of this article, is defined by its unique

Employer Identification number (EIN) issued by the

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Firms operate in one

industry or in multiple industries. An enterprise is a firm or

a combination of firms that engages in economic activities

which are classified into multiple industries. An enterprise

may report under one or a number of EINs.

Data users often request data at one of these levels on

the assumption that the specific level sought is critical to

their analytical purpose. But are such levels of

aggregation significantly different? In this article, we

present a profile of U.S. businesses at all three levels and

quantify the differences in magnitude and trends. In

particular, we estimate gross job flows by size class at the

establishment, firm, and enterprise levels and assess the

effect of aggregation on the level and trend of gross job

flows.

Akbar Sadeghi is an economist in the Office of

Employment and Unemployment Statistics, U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

David M. Talan

talan.dave@bls.gov

David M. Talan is Chief, Division of

Administrative Statistics and Labor Turnover,

Office of Employment and Unemployment

Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Richard L. Clayton

clayton.rick@bls.gov

Richard L. Clayton is an economist in the Office

of Employment and Unemployment Statistics,

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

We analyzed our data by size class because many users wish to track economic data by size and believe that

the unit of classification is important. The perception is that multiunit businesses act as a whole rather than as a

collection of individual establishments. On the one hand, it could be that larger multiunit businesses make more

unified decisions to control hiring, close a plant or store, or lay off workers during economic downturns. This

argument supports the use of a higher level of aggregation than the establishment level. On the other hand,

businesses might make such decisions on the basis of each establishments profitability, product line, and

longer term prospects for contributions to the overall business. Why restrict hiring at a fully profitable and

growing location when other locations are suffering from insufficient demand? In this case, the firm may act

more like a set of individual establishments rather than a unified set of establishments.

When it comes to EIN-defined firm-level data, as opposed to the enterprise-level data for multilocation

businesses, the same argument for unified decisions at the top of the corporate structure favors data at the

enterprise level. However, businesses, especially large ones, may use different EINs not merely for

administrative purposes, but for economic reasons, such as making a deliberate distinction in their operation in

accordance with the heterogeneity of their economic activities (e.g., differentiating between manufacturing, on

the one hand, and retail and services, on the other). This distinction could also be based on giving a subsidiary

independence in its decisionmakinga distinction that is highly relevant in selecting a unit of analysis.

Therefore, there are benefits in recognizing the EIN as a distinct company identifier and not combining many

heterogeneous economic activities of a large enterprise into one unit of analysis.

Most businesses are single-establishment firms. Establishment-level data allow each individual location to be

classified into a specific industry. This kind of classification is critically important to local decisionmakers and to

businesses deciding where to locate.

For multiestablishment businesses, firm-level data are important for understanding corporate-level decisions.

However, multiestablishment firms do not always respond uniformly to economic events. Corporate

decisionmakers may make decisions that are based on overall corporate objectives or, alternatively, may look at

specific product lines and specific demand conditions. For example, a chain of restaurants might respond to a

nationwide recession by reducing hiring uniformly in order to preserve cash levels. Or the corporate leadership

might examine specific locations for slumping demand and restrict hiring in those locations or, instead, decide to

close unprofitable locations on a case-by-case basis. One could argue that, if the firm makes case-by-case

decisions, then it is really acting more like a series of establishments. Note that we are focused here on the

decisions of establishments, firms, and enterprises that affect employment and wages. Enterprise-level data,

like firm-level data, are needed to understand the behavior of the national economy, top-to-bottom

decisionmaking, corporate planning, and policymaking as they relate to employment and wages. Also,

corporate-level data at the highest level of aggregation may be useful for international comparisons.

Firm- and enterprise-level data present some issues for users. For example, many firms cross state lines,

making accurate state or local data somewhat difficult to construct. Furthermore, firms in more than one industry

pose similar issues regarding the accuracy of data. If we place the entire firm in a single, perhaps dominant

industry, we may overstate the significance of one industry while understating the others.

Table 1 gives a summary of uses, along with the strengths and weaknesses, of the foregoing units of analysis.

To have a better understanding of corporate business decisions, we need data at all three levels of aggregation.

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

However, when data are not available at all levels, we need to know the significance of the differences.

Quantifying these differences is the motivation for this article.

Table 1. Units of analysis: a comparative view

Unit of analysis

Establishment

Uses

Strengths

Weaknesses

Measuring economic

activity at precise industry

and geographic locations.

Data are available at the

national, state, and

county levels.

Measures economic activity at the precise

geographic (down to the county level) and

detailed industry level (up to the six-digit NAICS

code).

Establishment-level data are critical to the full

range of local decisions on training and economic

development.

At this level, comparisons across other local

levels are possible if firm or enterprise identifiers

are available. Higher level data (firm or

enterprise) lose the ability to profile accurately by

industry because cross-industry businesses

cannot be uniquely assigned to a single industry.

May not be the unit that

determines economic

decisions (profit

maximization, hiring,

etc.).

Establishment data may

not demonstrate the

parent company's

behavior.

Firm

Measuring economic

activity in

multiestablishment firms.

Measures firm behavior and how firms adjust to

economic conditions.

Less precise industry

and geographic

information, because a

firm may have multiple

locations and multiple

industries.

Enterprise

Measuring economic

activity at the corporate

level.

National and international

comparisons (global

supply chains) are

possible.

Measures enterprise behavior and how

enterprises adjust to economic conditions.

Data at this level are needed for the full national

picture and full business behavior view. Also,

enterprise level data are valued for comparisons

at the international level.

Less precise industry

and geographic

information, because an

enterprise may have

multiple locations and

multiple industries.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: First, we discuss business identifiers of the establishment, firm,

and enterprise level. Next, we report on the profile of U.S. multilocation businesses by enterprise and contrast

those businesses with businesses at the firm level. Then, we report the results of Business Employment

Dynamics (BED) gross job gains and losses at the establishment, firm, and enterprise levels by aggregating job

flows for companies with single and companies with multiple tax identification numbers. Finally, we evaluate

whether adopting the enterprise structure and generating data at a broader definitional level will change our

interpretation of the BED firm-size data in any way.

Business identifiers at the establishment, firm, and enterprise levels

Federal statistical agencies collect different business identifiers. Some agencies can publish business data at

one or more levels on the basis of the availability of these identifiers. For example, the Bureau of Labor

Statistics (BLS) business universe frame, the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), measures

business activity at the lowest level possible: the establishment level. For multiunit businesses, establishmentbased information is important so that each establishmentalong with its employment and wagescan be

placed in the correct industry and specific geographic location. The QCEW obtains the breakouts for multiunit

businesses from its Multiple Worksite Report (MWR). This quarterly report is obtained under unemployment

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

insurance (UI) reporting laws with built-in detail that makes the QCEW a unique business register in its degree

of accuracy at the establishment level. The MWR promptly identifies establishment births and deaths, because

businesses must report new locations and because they have an incentive to show closing locations.

The QCEW, however, is essentially an establishment-based business register. The establishment-based

reporting serves well for survey sampling. It is critical that survey samples represent the universe of

businessesan achievement that can be done only with an accurate depiction of the business details. The

QCEW can also publish data at the firm level, given that the EIN identifier for each record represents a legal

entity for a vast majority of multiestablishment employers that operate across different industries and regions in

the private sector. The QCEW does not, however, have an enterprise identifier through its normal reporting and

lacks data collection vehicles to link EINs under common ownership and control.

The IRS requires all active businesses to file a federal income tax return. Parent companies have the option of

filing a consolidated return for all affiliated companies or filing separate returns. Because the IRS is unable to

obtain establishment breakouts for multiunit businesses, it publishes data from its bulletin Statistics of Income

generally at the firm level and not fully at the enterprise level.

The U.S. Census Bureau is able to collect establishment-level data from its Economic Census every 5 years

and data on those businesses with employment greater than 250 in the intervening years. The Census Bureau

identifies the enterprise as the entire economic unit that is under common ownership or control (defined as

owning more than 50 percent of the voting stock). An enterprise includes all establishments, subsidiaries, and

divisions with the same or different EINs under the same ownership. The Census Bureau also obtains EINbased data from the IRS regularly and updates the information annually from the Report of Organization Survey

and other surveys.

The QCEW longitudinal database contains both establishment and firm identifiers. BLS obtained enterprise

linkages under a data-sharing agreement with the Census Bureau in 2012. As a part of this agreement, we

incorporated the Census-assigned enterprise codes into the QCEW longitudinal database and developed new

BED data for enterprises. Currently, in the BED job flow calculation, the establishment-level data are measured

by tracking employment changes at a single unit identified by unemployment insurance (UI) numbers and

reporting unit numbers (RUNs), and the firm-level data are measured by aggregating employment for all

establishments under the same EIN. The Census enterprise code provides a new level of aggregation

encompassing all of the various activities of the same parent company that are reported under different EINs.

Multilocation businesses: a profile

In March 2011, Census files had information on 168,000 multiunit enterprises that owned and operated

approximately 1.9 million establishments across the nation. The 168,000 parent companies in the Census

business register represented 301,000 EINs. The difference between the number of parent companies and the

number of EINs reveals that companies possess and report more than one EIN and shows the extent of the

difference in the number of businesses using the EIN or the Census company code as a business identifier.

However, in 2011, a total of 128,000 multilocation companies reported only one EIN. That leaves 40,000

businesses with multiple EINs, according to the Census business register. During the same period, using the

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

EIN as the parent company identifier, the QCEW reported that a total of 294,000 multilocation firms owned 2.3

million establishments. (See table 2.)

Table 2. Profile of Census Bureau and QCEW multiestablishment businesses, 200711 (in thousands)

Census Bureau file

QCEW file

Category

2007

Number of enterprise codes

Number of EINs

Number of establishments

2008

2009

2010

2011

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

186

177

176

173

168

317

311

309

305

301

281

289

291

289

294

1,844 1,872 1,866 1,878 1,885 2,190 2,283 2,323 2,306 2,346

Note: Dash indicates QCEW has no enterprise codes.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Enterprise vs. firm vs. establishment

Do the 40,000 enterprises with more than one EIN make a significant difference in the measures of employment

dynamics? Employment dynamics measure job flows in terms of business births, deaths, growth, and decline

over a given period (a quarter or a year) and measure net employment change as the difference between job

inflows and job outflows. This approach is in contrast to the standard static employment data, which show

employment levels at various points in time and measure changes as the difference between levels. The BED

program measures gross job gains created by units that open or expand, and gross job losses by units that

close or contract, over the course of a quarter or a year.1 The magnitude of these gains and losses depends on

whether the unit of analysis is an establishment or a firm. For single establishments, which constitute two-thirds

of the total records in the BED and 43 percent of total employment, this distinction is irrelevant, since the

establishment is the firm. For multilocation firms, however, the estimates of job flows by openings, closings,

expansions, and contractions at the firm level are lower than they are at the establishment level. The reason is

that expansions in some units of a multiestablishment firm may be offset by contractions in other units and make

the total expansions or contractions for the firm less than the sum of the individual expansions or contractions.

Moreover, if a multilocation retailer opens a new branch, it would be counted as an opening at the establishment

level but an expansion at the firm level. The net change in employment will not be affected by the unit of

measurement. However, both flow measures and net change will be different with regard to employment

dynamics by size class.

In the QCEW, firms are identified by EIN, which is a reasonable proxy for identifying firms in the BED size-class

data. However, table 2 shows that some firmsespecially large firms operating across many states and

industriespossess more than one EIN, for a variety of reasons.2 Through its Economic Census and Annual

Report of Organization Surveys, the Census Bureau has identified these companies and lists them under the

same ownership by issuing a company identifier or an enterprise code. We merged the Census multifirm

records with QCEW data by their common EINs, transferred company code information from the Census file into

the QCEW, and calculated the BED by aggregating employment for all establishments under the same

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

enterprise code. We then compared the results of the BED calculation of gross job gains and gross job losses at

the enterprise level with the corresponding results at the firm and establishment levels. Table 3 shows the

differences in gross job flows, as well as the number of units at the national level, among these three units of

measurement.

Table 3. BED levels and flows, by unit of analysis, March 2010 and March 2011 (in thousands)

Employment level

Level of aggregation

Employment

Establishment

Firm

Enterprise

Number of units

Establishment

Firm

Enterprise

Gross job gains

March

March

Net

2010

2011

change

103,524

103,525

103,525

105,430

105,431

105,431

6,672

4,799

4,721

6,707

4,823

4,744

Total

1,905 11,621

1,906 9,225

1,906 8,745

34

24

24

2,506

1,793

1,759

Gross job losses

Expanding Opening

units

units

Total

Contracting Closing

units

units

8,331

7,047

6,627

3,289 9,715

2,178 7,319

2,118 6,839

6,645

5,215

4,789

3,070

2,104

2,050

1,732

1,224

1,192

774 2,381

569 1,686

567 1,654

1,642

1,140

1,111

740

546

543

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As expected, the net employment change remains the same for all levels of aggregation, but the magnitude of

gross job flows varies with the unit of analysis chosen. There is a higher level of churning when job flows are

estimated at a lower level of aggregation (the establishment). At a higher level of aggregation (the enterprise or

firm), expansions in some units offset contractions in other units, leaving job flows at a lesser magnitude. For

example, if a multiunit firm expands employment in some units and reduces employment in others over a given

period, so that the total employment of the firm remains unchanged over the period, then the impact of labor

turnover in the firm on both total gross job gains and total gross job losses will be zero. However, job gains and

losses at single units of this firm will add directly to the total gross job gains and gross job losses when

estimated at the establishment level. For this reason, gross job gains and gross job losses are always higher at

the establishment level than the firm level, and at the firm level than the enterprise level. Similarly, the number of

openings and employment from openings are also lower at the enterprise level than at the firm and

establishment levels. These openings are counted as expansions at a higher level of definition of a firm.

The gap between BED data elements measured at the firm level and at the enterprise level is not as significant

as the gap between BED data elements measured at the firm level and at the establishment level. For the total

number of units, there were 6,707,000 active establishments in the U.S. private sector in March 2011, compared

with 4,823,000 active firms and 4,744,000 active enterprises. The difference between the number of firms and

the number of enterprises suggests that, for the year ending March 2011, a total of 79,000 firms in the BED

could have been linked with other firms.3 The enterprise data showed 2,349 fewer openings and 2,551 fewer

closings in the same period and reduced both the number of job-gaining firms and the number of job-losing

firms by 32,000 each. The enterprise aggregation reduced the total gross job gains and total gross job losses by

480,000 jobs each. The 480,000 figure represented 5.5 percent of total gross job gains.

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

In addition to producing effects on the magnitude of gross job flows, a higher level of aggregation affects the

size distribution of employers across the nine size-class categories that the BED publishes. (See tables 4 and

5.) We found that the enterprise-level data have less employment in each of the eight size-class categories up

to 999 employees and more employment in the size-class category of 1,000 or more employees. We found

nearly the same thing for the number of units: the enterprise aggregation reduces the number of units in all nine

size classes, with a higher reduction in the smaller size classes.

Table 4. Annual BED levels and flows, by size class at the enterprise level of aggregation, March 2010

March 2011 (in thousands)

Employment level

Initial size class

Employment

Total

1 to 4 employees

5 to 9 employees

10 to 19 employees

20 to 49 employees

50 to 99 employees

100 to 249 employees

250 to 499 employees

500 to 999 employees

1,000 or more employees

Number of units

Total

1 to 4 employees

5 to 9 employees

10 to 19 employees

20 to 49 employees

50 to 99 employees

100 to 249 employees

250 to 499 employees

500 to 999 employees

1,000 or more employees

Gross job gains

March

March

Net

2010

2011

change

103,525

5,479

6,162

7,531

10,426

7,341

8,839

5,860

5,549

46,338

105,431

6,049

6,253

7,609

10,559

7,448

9,016

5,998

5,650

46,848

1,906

571

91

77

133

107

177

138

101

510

4,721

2,676

938

561

348

107

58

17

8

8

4,744

2,694

941

563

349

107

58

17

8

8

Total

Gross job losses

Expanding Opening

units

units

Contracting Closing

Total

units

units

8,745

1,699

1,075

1,067

1,221

722

731

423

334

1,474

6,627

919

669

711

882

584

662

406

326

1,469

2,118 6,839

781 1,128

406

984

356

989

339 1,087

137

615

69

554

17

285

8

233

5

964

4,789

387

596

659

780

474

474

257

224

937

2,050

742

388

331

307

141

80

28

8

26

24 1,759

18

931

3

337

2

228

1

159

0

54

0

31

0

10

0

5

0

5

1,192

468

273

201

147

52

31

10

5

5

567 1,654

462

761

63

383

27

256

12

164

2

50

1

26

0

7

0

3

0

3

1,111

317

323

231

153

48

25

7

3

3

543

444

60

25

11

2

1

0

0

0

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Table 5. Annual BED levels and flows, by size class at the firm level of aggregation, March 2010March

2011 (in thousands)

Employment level

Initial size class

Gross job gains

March

March

Net

2010

2011

change

Employment

See footnotes at end of table.

Total

Expanding Opening

units

units

Gross job losses

Total

Contracting Closing

units

units

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

Table 5. Annual BED levels and flows, by size class at the firm level of aggregation, March 2010March

2011 (in thousands)

Employment level

Initial size class

Total

1 to 4 employees

5 to 9 employees

10 to 19 employees

20 to 49 employees

50 to 99 employees

100 to 249 employees

250 to 499 employees

500 to 999 employees

1,000 or more employees

Number of units

Total

1 to 4 employees

5 to 9 employees

10 to 19 employees

20 to 49 employees

50 to 99 employees

100 to 249 employees

250 to 499 employees

500 to 999 employees

1,000 or more employees

Gross job gains

March

March

Net

2010

2011

change

103,525

5,502

6,221

7,685

10,974

8,236

10,609

7,285

7,120

39,892

105,431

6,082

6,320

7,772

11,132

8,372

10,819

7,426

7,222

40,285

1,906

580

98

86

159

136

210

141

102

393

4,799

2,686

946

572

365

120

70

21

10

9

4,823

2,704

949

574

366

120

70

21

10

9

Total

Gross job losses

Expanding Opening

units

9,225

1,712

1,090

1,092

1,289

810

862

508

421

1,440

7,047

929

681

731

937

659

782

489

406

1,432

24 1,793

18

934

3

340

2

233

1

167

0

60

0

37

0

12

0

6

0

5

1,224

470

276

206

155

58

36

12

6

5

units

2,178

783

408

361

352

151

81

20

15

8

Total

Contracting Closing

units

units

7,319

1,132

991

1,005

1,130

674

652

368

319

1,047

5,215

388

601

669

812

523

565

334

303

1,019

2,104

744

390

336

319

151

87

34

16

28

569 1,686

463

763

64

386

27

261

12

171

2

55

1

31

0

9

0

5

0

4

1,140

318

326

235

160

53

31

9

5

4

546

445

61

26

11

2

1

0

0

0

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Are these changes large enough to have significant implications for the relative contributions of small and large

firms to employment growth? Table 6 shows the share of the net employment change for each size class, for the

year ending March 2011, for all three levels of aggregation. There is a wide gap between the size-class shares

at the establishment level, on the one hand, and both firm and enterprise levels, on the other. The shares,

however, are moderately close between the firm and enterprise levels. Data show that a shift from the firm to the

enterprise level of aggregation reduces the share of companies with 1 to 999 employees by 6.2 percentage

points and increases the share of companies with 1,000 or more employees by the same magnitude. The

change, however, does not alter the ranking of each size class or the relative contribution of each to the total net

change. Firms with 1 to 4 employees remain the largest contributors, followed by firms with 1,000 or more

employees. Other size classes also kept their relative rankings unchanged under both definitions.

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

Table 6. Share of annual net employment change, by size and level of aggregation, March 2010March

2011 (in percent)

Size class (number of employees)

Total

1 to 4

5 to 9

10 to 19

20 to 49

50 to 99

100 to 249

250 to 499

500 to 999

1,000 or more

Establishments Firms Enterprises

100.0 100.0

43.7 30.4

9.6

5.2

8.0

4.5

11.5

8.3

8.3

7.2

11.8

11

3.2

7.4

.6

5.4

3.4 20.6

100.0

30.0

4.8

4.1

7.0

5.6

9.3

7.2

5.3

26.8

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Figure 1 shows the share of net employment change by size class for all three levels of aggregation. One

finding is that, between the firm and establishment levels, there is a shift in share from establishments with 1 to

249 employees to firms with 250 or higher, while there is a shift in share from firms with 1 to 999 employees to

firms with 1,000 or more employees between the firm and enterprise levels.

How do the two measures differ over a longer timeframe and over the phases of business cycles? The

differences in the BED data elements between using EINs and using the enterprise codes as shown in tables 3

5 highlight only one observation: for the year ending March 2011. Looking over the period from 2007 to 2011, we

matched the enterprise codes and corresponding EINs, and merged them with QCEW EINs from the third

quarter of 1992 to the first quarter of 2012. The enterprise identifiers for 2007 were used for all quarters prior to

March 2007, and the enterprise codes for 2011 were used for 2012 merged records. The standard BED

tabulating procedures and the dynamic-sizing method were applied in calculating gross job gains and gross job

losses at the enterprise level. The series were then seasonally adjusted and compared against the same

estimates at the firm and establishment levels. Figures 2ac, 3 ac, and 4 ac show the net employment

change, gross job gains, and gross job losses by major size classes.

Two findings emerge from these figures. First, gross job flows by size class at the enterprise level are very close

to gross job flows at the firm level. Second, the gap between the two series is stable and does not change

noticeably over time, making the patterns similar. In particular, business cycle properties of the series remain

intact and the increase in gross job losses and the drop in gross job gains and in net employment change

coincide in both the 2001 and 200709 recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. In

a similar study comparing size classes by firm and establishment data,4 the peak-to-trough analysis yielded two

findings: similar cyclical movements, and different magnitudes of net employment change, across all nine size

classes. Adding an enterprise level to the mix, we found similar cyclical movements and an extremely close

magnitude of net employment change between the firm and enterprise size classes. Compared with firm-level

data, BED enterprise size-class data are slightly lower in gross job gains, gross job losses, and net employment

changes in size classes of less than 1,000 employees and higher in enterprises with 1,000 or more employees.

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

However, as table 6 shows, the relative ranking of the size classes in terms of their contributions to employment

growth remains unchanged.

We also made annual estimates of gross job gains and losses for 2007 through 2012. The results are shown in

figure 5, and they indicate that the differences in the magnitude of gross job gains and gross job losses between

the firm and enterprise levels are somewhat larger than they are in the quarterly data (because of a higher level

of job flows in the annual estimation). Even then, the gap remained stable and showed more consistency over

time.

Conclusion

The BED quarterly and annual enterprise-level series were consistently close to the firm-level series, and the

size-class data based on both levels of aggregation were not substantially different and followed a similar

pattern of peaks and troughs over the business cycle. With these findings, it appears that the current BLS

approach of using employers EINs as a proxy for company identifiers generates firm-based employment

dynamics data that are uniform, dependable, and consistent with other employment series, including Census

Bureau data. Although there are differences in the level of job flows based on firm and enterprise estimates, the

similarity in the trend data, stability in the relative share of the size-class data, and the fact that BLS data are

more frequent (quarterly) and more up to date (available 7 months after the close of the quarter) provide users a

powerful tool for understanding employment dynamics. However, data sharing and the use of the Census

enterprise code on a continual basis will help BLS to identify parent companies within the QCEW business

register.

The QCEW and Census business registers are both coherent and consistent by themselves, but there are

differences in their source, the periodicity of the data, and their definitions and collection methods. The Census

data come mainly from the Economic Census and annual Report of Organization Surveys and other

administrative records. The QCEW data, by contrast, are compiled from a single source: the quarterly

contribution reports on the employment and wages of workers covered by UI law. The QCEWs business

register is updated quarterly, whereas the Census business register is updated on a broad basis every 5 years

by the Economic Census and on a limited basis annually. Despite difficulties in matching records, the

information in these two registers, which is derived from different sources, can complement each other and, if

shared, can improve the quality of both registers, especially if used for all records. The QCEW provides data on

employment and wages, and information on mergers, acquisitions, spinoffs, and other corporate restructurings,

on a quarterly basis. The information is robust, accurate, and timely at the establishment level as well as at the

EIN-based firm level. The Census business register carries valuable information on corporate structures and

company organizations across states. Both statistical agencies can benefit from sharing various aspects of their

registers.

10

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

11

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

12

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

13

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

14

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

15

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

NOTES

1

For a thorough description of the concepts, linkage methodology, and definitions associated with BED, see James Spletzer,

Jason Faberman, Akbar Sadeghi, David Talan, and Richard Clayton, Business employment dynamics: new data on gross job

gains and losses, Monthly Labor Review, April 2004, pp. 2942, http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2004/04/art3full.pdf.

2

For reasons when a new EIN is needed, see Do you need a new EIN? (Internal Revenue Service, July 14, 2016), http://

www.irs.gov/Businesses/Small-Businesses-&-Self-Employed/Do-You-Need-a-New-EIN.

3

79,000 is the difference between the number of firms defined by EINs and the number of firms defined by the Census Bureau

company identifiers.

4

See Sherry Dalton, Erik Friesenhahn, James Spletzer, and David Talan, Employment growth by size class: firm and

establishment data, Monthly Labor Review, December 2011, pp. 312, http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2011/12/art1full.pdf.

RELATED CONTENT

Related Articles

High-employment-growth firms: defining and counting them, Monthly Labor Review, June 2013.

Linking firms with establishments in BLS microdata, Monthly Labor Review, June 2013.

The declining average size of establishments: evidence and explanations, Monthly Labor Review, March 2012.

Employment growth by size class: firm and establishment data, Monthly Labor Review, December 2011.

16

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

MONTHLY LABOR REVIEW

The births and deaths of business establishments in the United States, Monthly Labor Review, December 2008.

Business employment dynamics: new data on gross job gains and losses, Monthly Labor Review, April 2004.

Related Subjects

Employment

Firm size

BLS Programs and surveys

Statistical programs and methods

17

You might also like

- Advantages: Home Current Ratio Analysis Debt Ratio Analysis Financial Ratio Analysis Quick Ratio AnalysisDocument7 pagesAdvantages: Home Current Ratio Analysis Debt Ratio Analysis Financial Ratio Analysis Quick Ratio AnalysisSabiya MbaNo ratings yet

- Alk Bab 5Document2 pagesAlk Bab 5RAFLI RIFALDI -No ratings yet

- The Role of Statics in BusinessDocument6 pagesThe Role of Statics in Businessanam.naichNo ratings yet

- Be Careful When Doing BusinessDocument14 pagesBe Careful When Doing BusinessLucky RawatNo ratings yet

- Book Issue Part 1Document25 pagesBook Issue Part 1amanNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship: Why It MattersDocument2 pagesEntrepreneurship: Why It Mattersbaloch75No ratings yet

- Ratio AnalysisDocument24 pagesRatio Analysisrleo_19871982100% (1)

- Financial Ratio Analysis Term PapersDocument7 pagesFinancial Ratio Analysis Term Papersafdtvuzih100% (1)

- AssignmntDocument2 pagesAssignmntRajat Gupta50% (2)

- Adapting The Balanced Scorecard To Fit The Public and Nonprofit SectorsDocument3 pagesAdapting The Balanced Scorecard To Fit The Public and Nonprofit SectorspboricNo ratings yet

- Accounting Ratios PDFDocument3 pagesAccounting Ratios PDFfrieda20093835No ratings yet

- Thesis Financial Statement AnalysisDocument5 pagesThesis Financial Statement Analysisheatheredwardsmobile100% (1)

- Financial AnalyticsDocument8 pagesFinancial AnalyticsSanjana Gowda B NNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratios Case Homeowork 3Document17 pagesFinancial Ratios Case Homeowork 3Edward Lu100% (1)

- Synopsis Ratio AnalysisDocument3 pagesSynopsis Ratio Analysisaks_swamiNo ratings yet

- MBA AssignmentDocument2 pagesMBA AssignmentAnmol SharmaNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument80 pagesFinancial Ratio AnalysisRajesh BathulaNo ratings yet

- Financial Health in Terms of Profitabilty and LiquidityDocument49 pagesFinancial Health in Terms of Profitabilty and Liquiditymilind_iiseNo ratings yet

- G20 Set MethodologyDocument22 pagesG20 Set MethodologymsriramcaNo ratings yet

- Adapting The BSC To Fit The Public and Nonprofit SectorsDocument5 pagesAdapting The BSC To Fit The Public and Nonprofit SectorsLaine GhisNo ratings yet

- What Is A PEST AnalysisDocument12 pagesWhat Is A PEST AnalysistanjialijlNo ratings yet

- Buy-Side Business Attribution - TABB VersionDocument11 pagesBuy-Side Business Attribution - TABB VersiontabbforumNo ratings yet

- What Does Ratio Analysis Tell Us ?Document1 pageWhat Does Ratio Analysis Tell Us ?StrikerNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocument14 pagesFinancial Statement AnalysisJosephine MoranteNo ratings yet

- Cma ProjectDocument14 pagesCma ProjectAbhishek SaravananNo ratings yet

- Minhaj University: Corporate Finance AssignmentDocument6 pagesMinhaj University: Corporate Finance AssignmentNEHA BUTTTNo ratings yet

- FM Brand MarketingDocument23 pagesFM Brand MarketingMadhav ShenoyNo ratings yet

- The Right Role For Multiples in ValuationDocument5 pagesThe Right Role For Multiples in Valuationedusho26100% (1)

- Case Study - Comparative Financial StatementsDocument6 pagesCase Study - Comparative Financial StatementsCJNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Company Income TaxDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Company Income Taxrdssibwgf100% (1)

- What Is A Business ReportDocument10 pagesWhat Is A Business ReportSANSKAR JAINNo ratings yet

- Running Head: BUSINESS 1Document6 pagesRunning Head: BUSINESS 1sheeNo ratings yet

- Ent PRDocument8 pagesEnt PRShanthi KanagarasuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 01Document25 pagesChapter 01Frank Lee50% (2)

- Amazon Com. Inc. Financial Analysis Presentation of Financial StatementDocument2 pagesAmazon Com. Inc. Financial Analysis Presentation of Financial StatementNune SabanalNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratios and InterpretationDocument20 pagesFinancial Ratios and Interpretationtkt ecNo ratings yet

- Example Thesis On Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument8 pagesExample Thesis On Financial Ratio Analysisejqdkoaeg100% (1)

- FM AssignmentDocument5 pagesFM AssignmentSAPDHRUVNo ratings yet

- What Is A PEST AnalysisDocument13 pagesWhat Is A PEST AnalysistusharNo ratings yet

- Ratio AnalysisDocument9 pagesRatio Analysisbharti gupta100% (1)

- Ratio Analysis of BGPPLDocument53 pagesRatio Analysis of BGPPLmayurNo ratings yet

- Accounting Textbook Solutions - 32Document19 pagesAccounting Textbook Solutions - 32acc-expertNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Ratio Analysis of PC JewellerDocument23 pagesA Case Study On Ratio Analysis of PC JewellerAllen D'CostaNo ratings yet

- EBP - Applying InformationDocument10 pagesEBP - Applying InformationDarrylJanMontemayorNo ratings yet

- 6370a - Sbi Icici BankDocument59 pages6370a - Sbi Icici BankRamachandran RajaramNo ratings yet

- Accounting Information System Research PaperDocument8 pagesAccounting Information System Research Paperuylijwznd100% (1)

- 2012 Pia Financial Ratio StudyDocument22 pages2012 Pia Financial Ratio StudySundas MashhoodNo ratings yet

- Business Reports Methods and FormateDocument17 pagesBusiness Reports Methods and FormateShahzil NaqviNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On Financial Statement AnalysisDocument5 pagesTerm Paper On Financial Statement Analysisbujuj1tunag2100% (1)

- Research Paper Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Financial Ratio Analysisaflbmmmmy100% (1)

- Unveiling The Hidden NarrativesDocument4 pagesUnveiling The Hidden NarrativesLoki KuroNo ratings yet

- Accounting Theory and PracticesDocument46 pagesAccounting Theory and Practicesjhlim1294No ratings yet

- Kirchhoff Small Business Economics 1989 PP 65 - 74Document10 pagesKirchhoff Small Business Economics 1989 PP 65 - 74pthakerNo ratings yet

- Sample Financial Analysis Research PaperDocument4 pagesSample Financial Analysis Research Paperafnhicafcspyjh100% (1)

- CH 03Document30 pagesCH 03Mallika Grover100% (2)

- Accounts NotesDocument15 pagesAccounts NotessharadkulloliNo ratings yet

- Finance AnalysisDocument11 pagesFinance Analysissham_codeNo ratings yet

- BUS 800 Supplemental Chapter F 2015, W 2016Document16 pagesBUS 800 Supplemental Chapter F 2015, W 2016Charlie XiangNo ratings yet

- CPC Hearings Nyu 12-6-18Document147 pagesCPC Hearings Nyu 12-6-18TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- wp2017 25Document123 pageswp2017 25TBP_Think_Tank100% (7)

- Market Declines: What Is Accomplished by Banning Short-Selling?Document7 pagesMarket Declines: What Is Accomplished by Banning Short-Selling?annawitkowski88No ratings yet

- ISGQVAADocument28 pagesISGQVAATBP_Think_Tank100% (1)

- Rising Rates, Flatter Curve: This Time Isn't Different, It Just May Take LongerDocument5 pagesRising Rates, Flatter Curve: This Time Isn't Different, It Just May Take LongerTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Insight: Can The Euro Rival The Dollar?Document6 pagesInsight: Can The Euro Rival The Dollar?TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- HHRG 116 BA16 Wstate IsolaD 20190314Document4 pagesHHRG 116 BA16 Wstate IsolaD 20190314TBP_Think_Tank0% (1)

- The Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums SEDocument4 pagesThe Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums SETBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- WEF BookDocument78 pagesWEF BookZerohedge100% (1)

- Trade Patterns of China and India: Analytical Articles Economic Bulletin 3/2018Document14 pagesTrade Patterns of China and India: Analytical Articles Economic Bulletin 3/2018TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- DP 11648Document52 pagesDP 11648TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- pb18 16Document8 pagespb18 16TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Solving Future Skills ChallengesDocument32 pagesSolving Future Skills ChallengesTBP_Think_Tank100% (1)

- Inequalities in Household Wealth Across OECD Countries: OECD Statistics Working Papers 2018/01Document70 pagesInequalities in Household Wealth Across OECD Countries: OECD Statistics Working Papers 2018/01TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Working Paper Series: Exchange Rate Forecasting On A NapkinDocument19 pagesWorking Paper Series: Exchange Rate Forecasting On A NapkinTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- HFS Essay 2 2018Document24 pagesHFS Essay 2 2018TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Macro Aspects of Housing: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Globalization and Monetary Policy InstituteDocument73 pagesMacro Aspects of Housing: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Globalization and Monetary Policy InstituteTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Financial Stability ReviewDocument188 pagesFinancial Stability ReviewTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- The Level and Composition of Public Sector Debt in Emerging Market CrisesDocument35 pagesThe Level and Composition of Public Sector Debt in Emerging Market CrisesTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- F 2807 SuerfDocument11 pagesF 2807 SuerfTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- CB CryptoDocument16 pagesCB CryptoHeisenbergNo ratings yet

- Ecb wp2155 enDocument58 pagesEcb wp2155 enTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Work 726Document29 pagesWork 726TBP_Think_Tank100% (1)

- Working Paper Series: Wealth Effects in The Euro AreaDocument46 pagesWorking Paper Series: Wealth Effects in The Euro AreaTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Work 726Document29 pagesWork 726TBP_Think_Tank100% (1)

- R qt1806bDocument14 pagesR qt1806bTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Has18 062018Document116 pagesHas18 062018TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- CPP 1802Document28 pagesCPP 1802TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Succession PlanningDocument15 pagesSuccession Planningswartiwari100% (1)

- PLDT Inc. SWOT Analysis Strengths of PLDT IncDocument6 pagesPLDT Inc. SWOT Analysis Strengths of PLDT IncEricca Joyce AndradaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Computation of WagesDocument6 pagesNotes On Computation of WagesNashiba Dida-AgunNo ratings yet

- Esdc Ghjkemp5602 (215 11 005) eDocument14 pagesEsdc Ghjkemp5602 (215 11 005) ecutemayurNo ratings yet

- E2-Managing Performance at HaierDocument9 pagesE2-Managing Performance at Haiersanthosh_annamNo ratings yet

- Boone County Employee Satisfaction Final General SummaryDocument2 pagesBoone County Employee Satisfaction Final General SummaryAmr El Sheikh100% (1)

- Women Entrepreneurs 10Document23 pagesWomen Entrepreneurs 10Ginny Paul GabuanNo ratings yet

- SHRM HandbookDocument72 pagesSHRM HandbookVineeth Radhakrishnan100% (1)

- Bad CV Examples UkDocument7 pagesBad CV Examples Ukguj0zukyven2100% (2)

- (MPSDM) Rangkuman Uas 18Document46 pages(MPSDM) Rangkuman Uas 18blackraidenNo ratings yet

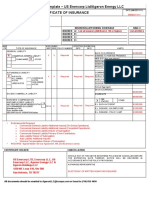

- Sample COI Template - US Enercorp Ltd/Ageron Energy LLC Certificate of InsuranceDocument1 pageSample COI Template - US Enercorp Ltd/Ageron Energy LLC Certificate of InsuranceMohamed Ashraf SolimanNo ratings yet

- Celestino & Co. v. Collector, 99 Phil. 841 (1956)Document3 pagesCelestino & Co. v. Collector, 99 Phil. 841 (1956)Winnie Ann Daquil Lomosad-MisagalNo ratings yet

- Skanska Recruitment BrochureDocument12 pagesSkanska Recruitment BrochureAlex ZinkoNo ratings yet

- Reimaging The Career Center - July 2017Document18 pagesReimaging The Career Center - July 2017Casey Boyles100% (1)

- Joe 21800Document11 pagesJoe 21800rihab trabelsiNo ratings yet

- Career Aspirations of Generation Y at Work Place PDFDocument5 pagesCareer Aspirations of Generation Y at Work Place PDFsudarshan raj100% (1)

- Maximising Resources To Achieve Business 1Document17 pagesMaximising Resources To Achieve Business 1Sainiuc Florin ValentinNo ratings yet

- Jacqueline Zegers CVDocument3 pagesJacqueline Zegers CVapi-203349164No ratings yet

- Study On Compensation and Benefits Its Influence oDocument8 pagesStudy On Compensation and Benefits Its Influence oStha RamabeleNo ratings yet

- International School V QuisumbingDocument8 pagesInternational School V QuisumbingMelgenNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in Leather IndustryDocument63 pagesChild Labour in Leather IndustryMohammad Nurun NobiNo ratings yet

- TVET Database Republic of Korea (Data Mengenai Perkembangan Vokasi Di Korea)Document13 pagesTVET Database Republic of Korea (Data Mengenai Perkembangan Vokasi Di Korea)malaiklimahNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction Among Employees of AutomotiveDocument4 pagesJob Satisfaction Among Employees of Automotivevishal kashyapNo ratings yet

- Objectives of Industrial RelationsDocument6 pagesObjectives of Industrial Relationsdeep_archesh88% (8)

- Disengagement of Older People in An Urban SettingDocument269 pagesDisengagement of Older People in An Urban SettingAdi AmarieiNo ratings yet

- StaffingDocument11 pagesStaffingHimanshu PatelNo ratings yet

- JPL Marketing v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesJPL Marketing v. Court of AppealsNelly Louie CasabuenaNo ratings yet

- Labour FDDocument36 pagesLabour FDSushrut ShekharNo ratings yet

- MEPI Tomorrow - S Leaders Flyer - 2Document1 pageMEPI Tomorrow - S Leaders Flyer - 2Aladdin HassanNo ratings yet

- Kulas Ideas & Creations, Gil Francis Maningo and Ma. Rachel Maningo, vs. Juliet and Flordeliza Arao-AraoDocument2 pagesKulas Ideas & Creations, Gil Francis Maningo and Ma. Rachel Maningo, vs. Juliet and Flordeliza Arao-AraodasfghkjlNo ratings yet