Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Darko Spasevski PDF

Uploaded by

faw03Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Darko Spasevski PDF

Uploaded by

faw03Copyright:

Available Formats

Darko Spasevski, Ph.

D1

The Role Of The Engineer In The Fidic Conditions Of Contracts

Abstract

The engineer has sifnificant role in the process of construction

contract administration. In general he can act as agent of the employer.

But his role is not restricted to agency relathionships. At the same tame he

is acting as independent arbitrator in the relations between the employer

and the contractor. The position of the engineer is defined by the

mandatory rules of the public law (for example in Macedonia that is Law

on Construction). If we extract the mandatory rules of public law, the next

most important document which is defining the role of engineer is the

contract itself. The international practice, first of all FIDIC, is plaing crutial

role in setting of the rules determining the engineers role. A lot of his

obligations towards the employer are rasing from the contract.

Key words: Engineer, Contractor, Employer

1.

Position of the Engineer according to the FIDIC Conditions

of Contract

The engineer has specific role into the process of execution of

construction contracts. He has large specter of responsibilities which are

determining his crucial role in the administration of construction contracts.

Contract administration involves making decisions and timely flow of

information and decisions to enable competion of the project as

required by the contract documents including review and observation of

the construction project.2 This is important to the Employer and the

Contractor because this is determining that the work is proceeding in

conformity with the agreement, and it allows a possibility to inspect if

there are inaccuracies, ambiguities or inconsistencies in the design.3 As it

can be seen, there are few terms describing the engineer, which including

architect and consultant. The termus used in this text, i.e. engineer,

1

Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law Iustinianus Primus - Skopje

http://csc-dcc.ca/Education/Construction+Contract+Administration/

3

Ibid.

2

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

Vol. 6:1

architect and consultant are considered as a synonyms.

Contract administration handles daily contractual issues in a

contract execution and copes with them in accordance with the progress

of the whole project. Contractual issue may be related to time, cost,

quality and other obligations set out in the contract.4

The basic structure of the engineers role in to the administration

of construction contracts is set by the the FIDIC Conditions of Contacts.

FIDIC is founded in 1913, and is charged with promoting and

implementing the consulting engineering industrys strategic goals on

behalf of its Member Associations and to disseminate information and

resources of interest to its members.5 Today, FIDIC membership covers

97 countries of the world. FIDIC, in the furtherance of its goals, publishes

international standard forms of contracts for works and for clients,

consultants, sub-consultants, joint ventures and representatives, together

with related materials such as standard pre-qualification forms.6 FIDIC

also publishes business practice documents such as policy statements,

position papers, guidelines, training manuals and training resource kits in

the areas of management systems (quality management, risk management,

business integrity management, environment management, sustainability)

and business processes (consultant selection, quality based selection,

tendering, procurement, insurance, liability, technology transfer, capacity

building).7

In this part of the text, next FIDIC documents worth to be

mentioned: 1) Conditions of Contract for Construction, 1999; 2)

Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design-Built, 1999; 3) Conditions

of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects,1999; 4) The Short Form

of Contract,1999; 5) ultilateral Development Banks (MDB) Harmonised

Conditions of Contract for Construction, 2005 and 6) Conditions of

Contract for Design, Build and Operate Projects, 2007.

The Red Book of 1999 is containign norms which are

representing equal balanced risk allocation between the Contractor and

Employer, especially in the parts concerining drawings and designs.

The Yellow Book (Conditions of Contract for Plant and

Design-Built) also is based on balanced risk allocation clauses, where the

risk for the drawings is on the side of the Contractor.

In the Conditions of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects or

the Silver Book, the large amount of the contractual risk is shift to the

Contractor. This is acceptable if we take in to consideration of the

4

Niralula Rajenda, Kusajagani Sjujni, ontract administration for a construction

project under FIDIC Red Book contract in Asian developing countries, aviable

at

http://management.kochi-tech.ac.jp/ssms_papers/sms118874_26c77ee7398a284f7160e5ef1a6f075e.pdf, accesed on 10.10.2014.

5

http://fidic.org/about-fidic, accesed on 1.10.2014.

6

Ibid.

7

Ibid.

2014

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

nature of turnkey concept of construction project. Here the role of contract

administration is complety different from the Red Book and the Yellob

Book because almost whole amount of the risk is in the hands of the

Contractor.

According to FIDIC Red and Yellow Book from 1999, clause

3.1., the employer shall appoint the engineer who shall carry out the

duties assigned to him in the contract. The Engineer according to this

FIDIC clause shall have no authority to amend the contract. But, the

engineer may exercise the authority attributable to the engineer as

specified in or necessarily to be implied from the contract. If the Engineer

is required to obtain the approval of the employer before exercising a

specified authority, the requirements shall be as stated in the particular

conditions. The employer undertakes not to impose further constraints on

the engineers authority, except as agreed with the contractor. However,

whenever the engineer exercises a specified authority for which the

employers approval is required, then (for the purposes of the contract)

according to FIDIC RED and Yeloow Book, the employer shall be

deemed to have given approval. Except as otherwise stated in clause 3.1.

of FIDIC Red and Yellow Book: a) whenever carrying out duties or

exercising authority, specified in or implied by the contract, the engineer

shall be deemed to act for the employer; (b) the engineer has no authority

to relieve either party of any duties, obligations or responsibilities under

the contract; and (c) any approval, check, certificate, consent,

examination, inspection, instruction, notice, proposal, request, test, or

similar act by the engineer (including absence of disapproval) shall not

relieve the contractor from any responsibility he has under the contract,

including responsibility for errors, omissions, discrepancies and noncompliances.

According to clause 3.2 of the FIDIC Red and Yellow Book, the

engineer may from time to time assign duties and delegate authority to

assistants, and may also revoke such assignment or delegation. These

assistants may include a resident engineer, and/or independent inspectors

appointed to inspect and/or test items of plant and/or materials. The

assignment, delegation or revocation shall be in writing and shall not take

effect until copies have been received by both parties. However, unless

otherwise agreed by both parties, the engineer shall not delegate the

authority to determine any matter in accordance with Sub-Clause 3.5 of

the FIDIC Red and Yellow Book.

Assistants shall be suitably qualified persons, who are competent

to carry out these duties and exercise this authority, and who are fluent in

the language for communications defined in the contract.

Each assistant, to whom duties have been assigned or authority

has been delegated, shall only be authorised to issue instructions to the

contractor to the extent defined by the delegation. Any approval, check,

certificate, consent, examination, inspection, instruction, notice, proposal,

request, test, or similar act by an assistant, in accordance with the

delegation, shall have the same effect as though the act had been an act of

the Engineer. However according to clause 3.2 of FIDIC Red and Yellow

Book: (a) any failure to disapprove any work, plant or materials shall not

constitute approval, and shall therefore not prejudice the right of the

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

Vol. 6:1

engineer to reject the work, plant or materials; (b) if the contractor

questions any determination or instruction of an assistant, the contractor

may refer the matter to the Engineer, who shall promptly confirm, reverse

or vary the determination or instruction.

The Engineer according to clause 3.3 of FIDIC Red and Yellow

Book may issue to the contractor (at any time) instructions which may be

necessary for the execution of the works and the remedying of any defects,

all in accordance with the contract. The contractor shall only take

instructions from the engineer, or from an assistant to whom the

appropriate authority has been delegated under this Clause. The contractor

shall comply with the instructions given by the engineer or delegated

assistant, on any matter related to the contract. These instructions shall be

given in writing.

According to clause 3.4 of the FIDIC Red and Yelow Book, if the

Employer intends to replace the engineer, the employer shall, not less

than 42 days before the intended date of replacement, give notice to the

contractor of the name, address and relevant experience of the intended

replacement engineer. The employer shall not replace the engineer with a

person against whom the contractor raises reasonable objection by notice

to the employer, with supporting particulars.

2.

Structuring the position of the Engeneer between the

Contractor and the Employer

Usualy will be expected that the mutual trust position will allow

any party to notifies to other of any events which may be reasons for

delay in the execution of the contract and will result with extra cost.

However, a contract requires the Contractor to notify the

Owner/Employer/Project Manager of the event or circumstances which

needs additional time and cost.8 The architect serving as a construction

administrator observes construction for conformity to construction

drawings and specifications.9 These documents are part of the legal

contract between the owner and general contractor.10 When interpreting

these legal documents, the architects role shifts. The architect serves not

as the owners direct agent but in a quasi- judicial capacity, showing

partiality to neither owner nor contractor.11 At other times during the

construction phase the architect acts as the owners representative and

Niralula Rajenda, Kusajagani Sjujni, ontract administration for a construction

project under FIDIC Red Book contract in Asian developing countries, aviable

at

http://management.kochi-tech.ac.jp/ssms_papers/sms118874_26c77ee7398a284f7160e5ef1a6f075e.pdf, accesed on 10.10.2014

9

Mays Patrick, Contract Administration, avialble at

http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents

/pdf/aiab089226.pdf, accesed on 10.8.2014.

10

Ibid.

11

Ibid.

2014

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

agent.12

The law presumes that the architect is aware of the whole of

the terms of the building contract under which he or she is acting.

That is fundamental to the architect s responsibilities.13 Unfortunately

too many architects have very limited knowledge of the contracts which

they purport to administer.14 The architect has no intrinsic powers by

virtue of being the architect under a particular contract, still less by virtue

of simply being an architect.15

The continuing involvement of the architect during the

construction phase helps assure the client that the completed building will

reflect the design intent, and further ensures the quality of materials and

workmanship.16 When the architect is retained by the owner to administer

the construction contract, the architect is the owners representative in

dealing with the contractor.17

A construction administrator needs substantial design and

construction experience, a thorough understanding of construction

techniques and methods, and the ability to interpret the intent of

construction documents.18 The construction administrator also needs a

thorough understanding of building codes, standards, and regulations as

well as the ability to communicate, negotiate, and resolve disputes with

trade personnel.

So far as claims are concerned, the architect may only act in the

way set out in the contract. If there is a pre - condition which must be

satisfied before the architect can act, such as the giving of notice by the

contractor, an architect who acts without that pre - condition is acting

without authority and may become liable to the employer. The exercise of

12

Ibid.

Chappell David, Building Contract Claims Fifth Edition, Wiley-Blackwell,

2011

14

Ibid.

15

Ibid.

16

Mays Patrick, Contract Administration, avialble at

http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents

/pdf/aiab089226.pdf, accesed on 10.8.2014.

17

The architect will be available for advice and consultation with the owner. In

monitoring the construction, the architect will be alert to whether the contractor

has carried out the design intent and the contract requirements relating to quality

of workmanship and materials. The architect will endeavor to guard the owner

against defects and deficiencies in the work. A general rule of thumb is that about

25 percent of the architects total compensation for services accounts for

construction administration. This fee percentage is generally sufficient to

compensate the architect for the following services during construction: 1)

Spending one day per week on site, attending a meeting and observing the

progress of construction, 2) Responding to questions from the contractors and

material suppliers, 3) Reviewing shop drawings and submittals, 4) Reviewing

and certifying monthly applications for payment, 5) Authoring clarifications and

minor changes to the documents, 6) Assisting consultants with construction

administration duties, 7) Record keeping and 8) Project closeout responsibilities.

Ibid.

18

Ibid.

13

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

Vol. 6:1

that discretion is so circumscribed by the terms of that provision of the

contract as to emasculate the element of discretion virtually to the point of

extinction.19

Architect and the quantity surveyor, if so instructed, have an

implied duty to carry out the ascertainment of direct loss and/or expense

within a reasonable time from the time that reasonably sufficient

information is received from the contractor.20

Very interesting for analysing is the case of Pacific Associates v

Baxter. Halcrow International Partnership were the engineers for work in

Dubai for which Pacific Associates were in substance the contractors

under a FIDIC contract. During the course of the work, the contractors

claimed that they had encountered unexpectedly hard materials and that

they were entitled to extra payment of some 31 million. Halcrow

refused to certify the amount and in due course, Pacific Associates sued

them for the 31 million plus interest and another item. It was claimed

that Halcrow acted negligently in breach of their duty to act fairly and

impartially in administering the contract. At fi rst instance, the court

struck out the claim, holding that Pacifi c Associates had no cause of

action. The court noted that: there was provision for arbitration between

19

However, more recently, it has been said: in the administration of a complex

contract, however, it is not uncommon to fi nd that the procedural requirements

of the contract are not followed to the letter. This is hardly surprising; if matters

seem straightforward or if the practical result that is desired is clear, the niceties of

procedure may not seem important, and there is an obvious temptation to ignore

them. In a construction contract most of the procedural requirements will be

matters with which the architect is directly involved on the employer s behalf.

Consequently the decision to dispense with procedural requirements is likely to be

that of the architect.Partington & Son (Builders) Ltd v Tameside Metropolitan

Borough Council (1985) 5 Con LR 99 at 108. Chappell David, op.cit. pp.143.

20

A reasonable time is a notoriously variable concept and the precise period

will depend on the relevant circumstances. However, it seems that an architect or

quantity surveyor who unreasonably delayed in the ascertainment of loss and/or

expense might be liable personally to either the employer or even to the

contractor. This proposition has received judicial support from an obiter

observation: [If] the period was unreasonable the chain of causation would be

completely broken. This might give rise to a claim against the architect . It is

tentatively believed that this is a correct statement of the law and it appears to be

supported by a clutch of other cases. In Michael Salliss & Co Ltd v ECA Calil ,

25 the contractor sued Mr and Mrs Calil and the architects, W F Newman &

Associates. It was claimed that the architects owed a duty of care to the contractor.

The claim fell into two principal categories: 1) failure to provide the contractors

with accurate and workable drawings and 2) failure to grant an adequate

extension of time and under - certifi cation of work done. The court held that the

architect had no duty of care to the contractors in respect of surveys, specifi

cations or ordering of variations, but that he did owe a duty of care in certifi

cation. It was held to be self - evident that the architect owed a duty to the

contractor not to negligently under - certify: If the architect unfairly promotes

the building employer s interest by low certification or merely fails properly to

exercise reasonable care and skill in his certification it is reasonable that the

contractor should not only have the right as against the owner to have the certifi

cate revised in arbitration but also should have the right to recover damages

against the unfair architect. Ibid.

2014

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

employer and contractor; and there was a special exclusion of liability

clause in the contract (clause 86) to which, of course, the engineers were

not a party, whereby the employers were not to hold the engineers

personally liable for acts or obligations under the contract, or answerable

for any default or omission on the part of the employer. The question of

whether a duty of care exists does not depend on the existence or absence

of an exclusion of liability clause although it may be one factor to be

considered.

Legally, the architect occupies three different positions as the

professional service phases progress from inception of design to

completion of construction contract administration. The three separate

and distinct roles recognized in law are: 1) as an independent contractor,

2) as an agent of the owner and 3) as a quasi-judicial officer.21

An independent contractor is one who contracts to do something

for another according to its own means and methods and not under control

of the employer except as to the end result.22

An agent is one who has the authority to act for another, called

the principal. After a contract has been entered into between the owner

and the contractor, the architects position changes.23

Some architects are inclined to shield the owner from some of the

unpleasant technical details that plague the construction process.24 This

could very well be a mistake, as some owners or their legal counsel might

interpret this to be a violation of the architects duty, as an agent, to

disclose. Concealment of relevant information from the owner could be

construed as fraud when there is a duty to disclose. Silence is often

interpreted as concealment.25

The architects third position is one of judge of the performance

of the owner and the contractor under terms of the contract. Some have

21

Mays Patrick, Contract Administration, avialble at

http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents

/pdf/aiab089226.pdf, accesed on 10.8.2014.

22

During the time the architect is conferring with the owner, designing the

project, preparing the contract documents, and administering the contract, the

architects relationship to the owner is as an independent contractor. The

architect contracts with the owner to furnish architectural services for which the

owner agrees to pay a fee. The architects and owners duties are spelled out in

the owner-architect agreement. Mays Patrick,

Contract Administration, avialble at

http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents

/pdf/aiab089226.pdf, accesed on 10.8.2014.

23

During the construction period, when the architect deals with the contractor

and others in behalf of the owner, the architect is serving as the owners agent.

However, the architects powers to obligate the owner are restricted to the extent

provided in the owner-architect agreement. When dealing with the contractor, the

architect acts in a fiduciary capacity for the owner and in this position of trust

must represent the owners best interests. As a fiduciary, the architect has the duty

to disclose to the owner all information that is material to the owners interests.

See: Mays Patrick, Contract Administration, op.cit.

24

Ibid.

25

Ibid.

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

Vol. 6:1

termed this position of the architect as being a friend of the contract.26

Arbitration tribunals and courts are inclined to look with suspicion

on contracts where final decisions on the performance of the parties are

made by a person under the control of one of the parties.27 Thus an

architects decision that is not fair, and is not seen to be fair, will be easily

overturned by arbitrators and judges on appeal.

List of references

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

26

Borham Atallah, Egypt, Knutson Robert, editor, FIDIC an

analysis of International Construction Contracts, Kluwer Law

International, 2005;

Bunni Nael, The FIDIC Forms of Contract, third edition, 2005;

Chappelli David, Cowlin Michael, Dunn Michael, Building Law

Encyclopedia, Wiley Blackwell, 2009;

Dabi Lj. Ugovor o finansiranju projekta (B.O.T. sistem) i ugovor o

podelji prozidovnje , Pravni ivot, br. 11/1996;

Eggleston Brian Liquidated Damages and Extensions of Time: In

Construction Contracts, Third Edition. Blackwell Publishing, 2009;

FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Construction, 1999;

FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design-Built, 1999;

FIDIC Conditions of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects,1999;

FIDIC The Short Form of Contract ,1999;

FIDIC he ultilateral Development Banks (MDB) Harmonised

Conditions of Contract for Construction, 2005;

FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Design, Build and Operate

Projects, 2007;

Frliet Marc, France, FIDIC An Analysis of International

All claims by the owner or contractor against each other should be referred to

the architect for initial decision as a condition precedent to more formal

procedures such as mediation and arbitration. Some claims will be those alleging

errors or omissions in the architects own actions or work product. The architect

must make even-handed, fair decisions strictly in accordance with the contract,

not siding with either party. The architect also must be a fair interpreter of the

documents. This can be difficult when the documents are imperfect and the

architects fair ruling will expose the documents to be at fault. When decisions on

the intent of the documents are made, they must be based on some tangible

evidence within the documents as to what is reasonably inferable and not merely

on what is in the architects mind. The architects decisions must be formulated

pursuant to procedural due process. This means that the architect must give

reasonable notice to each party to allow its position to be made known before the

architect makes a final decision.Arbitration tribunals and courts are inclined to

look with suspicion on contracts where final decisions on the performance of the

parties are made by a person under the control of one of the parties. Thus an

architects decision that is not fair, and is not seen to be fair, will be easily

overturned by arbitrators and judges on appeal. Ibid.

27

Ibid.

2014

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

Construction Contracts, Knutson Robert, Kluwer Law,

2006;

Gtz-Sebastian Dr. Hk, Are Civil Law Engineers fit for FIDIC?,

http://www.dr-hoek.de/EN/beitrag.asp?t=Germans-FitFor-FIDIC, 8.4.2012

Huse Joseph, Understanding and Negotiating Turnkey Contracts,

Sweet and Maxwell, London, 1997;

, FIDIC ,

Ugovori o graenju u

savremenoj meunarodnoj praksi, Pravni fakultet Beograd, 2011;

ICC Model Contract for the Turnkey Supply of and Industrial Plant,

2003;

ICC Model Trnkey Contracts for Major Projects 2007 ;

ICC Model Subcontract 2011 ;

ICE Design and Construction Conditions of Contracts, second

edition, 2001;

ICE The New Engineering Contract, edition 1995 and 2006;

Kanstatonis Vivian, Georgiades Stavros, Tieder B. John, An

overview of construction contracting under

greek law,

http://www.georgiades.com/publications/georgiades3.pdf,

2.11.2011;

Knutson Robert, England, FIDIC An Analysis of International

Construction Contracts, Knutson Robert, Kluwer Law,

2006;

Myers James, Giffune John, Miller Lisa, United States of America,

Knutson Robert, editor, FIDIC an analysis of International

Construction Contracts, Kluwer Law International, 2006;

Mays

Patrick,

Contract

Administration,

avialble

at

http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents/pdf/aiab089226.p

df, accesed on 10.8.2014.

Niralula Rajenda, Kusajagani Sjujni, ontract administration for a

construction project under FIDIC Red Book contract in Asian

developing countries, aviable at http://management.kochitech.ac.jp/ssms_papers/sms118874_26c77ee7398a284f7160e5ef1a6f075e.pdf, accesed on

10.10.2014

Powell-Smith&Furmston, Building Contract Casebook third

edition, 2000

Schneider Michael, Scherer Matthias, Switzerland, Knutson

Robert, editor, FIDIC an analysis of International Construction

Contracts, Kluwer Law International, 2006;

Speaight Anthony (editor), Architects Legal Handbook, Elsver ltd,

2010;

Totterdill Brian W., FIDIC users guide: A practical guide to the

1999 red and yellow books, Thomas Thelford, 2009;

Vukmir Branko, Ugovori o graenju i uslugama savetodavnih

inenjera, RRIF, Zagreb, 2009;

Vukmir Branko, Ugovori o izvodjenju investiciskih radova,

10

27.

Iustinianus Primus Law Review

Vol. 6:1

Zagreb, 1990;

Vuevi Milo, Lonar Milo, Ugovr o graenju, Pravni ivot,

br. 11/2002;

You might also like

- Role of Engineer PDFDocument10 pagesRole of Engineer PDFIbsa G. MesklNo ratings yet

- Duties and Liabilities of The Engineer SectDocument12 pagesDuties and Liabilities of The Engineer Sectmohammedamin oumer100% (1)

- Role of Engineer As Per FIDICDocument4 pagesRole of Engineer As Per FIDICSwapnil B. Waghmare100% (1)

- Cve522 LN Part 3Document19 pagesCve522 LN Part 3Dammy Taiwo-AbdulNo ratings yet

- General Conditions of Contract For Civil Works: Rev Oct 2000 1Document39 pagesGeneral Conditions of Contract For Civil Works: Rev Oct 2000 1MaiNo ratings yet

- Different Parties in Contract AdministrationDocument4 pagesDifferent Parties in Contract AdministrationJacky TamNo ratings yet

- Bidders Conference: Welcome ToDocument18 pagesBidders Conference: Welcome TomutamanthecontractorNo ratings yet

- Overview of Contract Law and Dispute ResolutionDocument42 pagesOverview of Contract Law and Dispute ResolutionFahim AnwerNo ratings yet

- LAWDocument13 pagesLAWGeorgina ChikwatiNo ratings yet

- General Conditions of Contract For Civil Works Annex IDocument30 pagesGeneral Conditions of Contract For Civil Works Annex Ijassim mohammedNo ratings yet

- Law 2Document32 pagesLaw 2Sisay HailegebriealNo ratings yet

- Unops General Conditions of Contract For Construction Works: Rev. 02, April 1995Document32 pagesUnops General Conditions of Contract For Construction Works: Rev. 02, April 1995the_gurjotNo ratings yet

- Contract Management - Vi Fidic, Conditions of Contract (FOR CONSTRUCTION WORKS - 1987/92 Edition)Document7 pagesContract Management - Vi Fidic, Conditions of Contract (FOR CONSTRUCTION WORKS - 1987/92 Edition)ideyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Stake Holder's Responsibility in Construction ProjectsDocument17 pagesChapter Three: Stake Holder's Responsibility in Construction ProjectsmunirNo ratings yet

- JCT MPF Brewer CommentaryDocument25 pagesJCT MPF Brewer CommentaryAtham W HussainNo ratings yet

- Construction Contract Law-1 For ShiftyDocument13 pagesConstruction Contract Law-1 For ShiftyStíofán BánNo ratings yet

- Hid - PRINCIPLES OF CONTRACT LAW AS APPLICABLE TO CIVIL ENGINEERINDocument3 pagesHid - PRINCIPLES OF CONTRACT LAW AS APPLICABLE TO CIVIL ENGINEERINbereket gNo ratings yet

- Ma Ritz and GerberDocument18 pagesMa Ritz and GerberAkshay ShankarNo ratings yet

- UNDP General Conditions of Contract For Civil WorksDocument40 pagesUNDP General Conditions of Contract For Civil WorksDharmarajah Xavier IndrarajanNo ratings yet

- The Fidic Provisions With Their Short Messages: Taken FromDocument48 pagesThe Fidic Provisions With Their Short Messages: Taken FromHayelom Tadesse GebreNo ratings yet

- SAFCEC Subcontract 2003 Rev 1Document30 pagesSAFCEC Subcontract 2003 Rev 1DirkieNo ratings yet

- FIDIC DeterminationDocument2 pagesFIDIC DeterminationMayank GhaiwatkarNo ratings yet

- Stekholders and ResponsblityDocument18 pagesStekholders and ResponsblityoraNo ratings yet

- Annex E - General Conditions of Contract For Civil WorksDocument37 pagesAnnex E - General Conditions of Contract For Civil WorksJoshua NdoloNo ratings yet

- Role of The Consultant in Construction, TheDocument14 pagesRole of The Consultant in Construction, Thesupernj100% (1)

- Design Risk in Fidic Contracts: Michael Black QCDocument17 pagesDesign Risk in Fidic Contracts: Michael Black QCAhmed AbdulShafiNo ratings yet

- Editorial April 2019 PDFDocument3 pagesEditorial April 2019 PDFVikas ThakarNo ratings yet

- Session 2 - FIDIC Notices - Deadlines - Responsibilities & Actions of The Parties (To Share)Document76 pagesSession 2 - FIDIC Notices - Deadlines - Responsibilities & Actions of The Parties (To Share)m Edwin100% (1)

- Construction Manager Role PGB 24mar08Document7 pagesConstruction Manager Role PGB 24mar08fakharkhiljiNo ratings yet

- Dispute in EPC ContractsDocument18 pagesDispute in EPC ContractsPriyanshu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Construction Manager Role PGB 3mar08Document5 pagesConstruction Manager Role PGB 3mar08SanjayNo ratings yet

- Clause 3: Adjustments) - The Contractor Is Required To Comply With Any Instruction Given byDocument25 pagesClause 3: Adjustments) - The Contractor Is Required To Comply With Any Instruction Given byKharisman LaiaNo ratings yet

- Eic Contractor S Guide To The Fidic Conditions of Contract For Epc Turnkey Projects The Silver BookDocument28 pagesEic Contractor S Guide To The Fidic Conditions of Contract For Epc Turnkey Projects The Silver BookSuzanne ChinnerNo ratings yet

- Contract Administration For A Construction Project Under FIDIC Red Book ContracDocument7 pagesContract Administration For A Construction Project Under FIDIC Red Book Contracthanlinh88100% (1)

- Avoiding Pitfalls in Construction - A Review of FIDIC Forms of ContractDocument5 pagesAvoiding Pitfalls in Construction - A Review of FIDIC Forms of ContractSohail MalikNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Role of EngineerDocument4 pagesFIDIC Role of Engineerfakharkhilji100% (2)

- Engineer/Contractor Relationship On Trunk Road ContractsDocument11 pagesEngineer/Contractor Relationship On Trunk Road ContractsΔημητρηςΣαρακυρουNo ratings yet

- Contractor's Obligation: Construct and Complete The Works Provide Everything Necessary, I.EDocument14 pagesContractor's Obligation: Construct and Complete The Works Provide Everything Necessary, I.EGenie LoNo ratings yet

- Section II - GCCDocument18 pagesSection II - GCCGechmczNo ratings yet

- Construction Works - Defects LiabilityDocument17 pagesConstruction Works - Defects LiabilityThabo SeaneNo ratings yet

- LAW6CON Dealing With Defective WorkDocument13 pagesLAW6CON Dealing With Defective WorkKelvin LunguNo ratings yet

- FAQs Comparison of ECC With ICE ConditionsDocument3 pagesFAQs Comparison of ECC With ICE ConditionsHarish Neelakantan100% (1)

- Construction Management Approach Based On FIDIC Conditions of Contract For Construction, 1999 1st EditionDocument38 pagesConstruction Management Approach Based On FIDIC Conditions of Contract For Construction, 1999 1st EditionAyub PramudiaNo ratings yet

- Contract Dhobley-Contruction - Reviewed DobelyDocument10 pagesContract Dhobley-Contruction - Reviewed DobelyBOBANSO KIOKONo ratings yet

- Responsibility of An Engineer in A Construction ProjectDocument45 pagesResponsibility of An Engineer in A Construction ProjectAruna JayamanjulaNo ratings yet

- Oregon State Board of Higher Education (Osbhe) CM/GC AgreementDocument18 pagesOregon State Board of Higher Education (Osbhe) CM/GC AgreementjhouvanNo ratings yet

- Claim in Red Book - FIdic Presentation - Ver03Document33 pagesClaim in Red Book - FIdic Presentation - Ver03Ngo Xuan Chinh88% (17)

- Case Study For Contract Management - Hydro Power Projects PDFDocument4 pagesCase Study For Contract Management - Hydro Power Projects PDFpradeepsharma62100% (1)

- Interim Determination of ClaimsDocument20 pagesInterim Determination of ClaimsTamer KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Contractual Suspension Terms - Password - RemovedDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Contractual Suspension Terms - Password - RemovedEmadNo ratings yet

- 30-Commercial SubContracts-Facilities PetrochemicalsDocument95 pages30-Commercial SubContracts-Facilities PetrochemicalsP Eng Suraj SinghNo ratings yet

- Contract AdmDocument11 pagesContract AdmgborglahselassieNo ratings yet

- c51 - Omugongo Presentation PDFDocument18 pagesc51 - Omugongo Presentation PDFengkjNo ratings yet

- Test 1 2015, Questions and Answers Test 1 2015, Questions and AnswersDocument5 pagesTest 1 2015, Questions and Answers Test 1 2015, Questions and AnswersNHLANHLA TREVOR NGCOBONo ratings yet

- Yangon Technological University Department of Civil EngineeringDocument19 pagesYangon Technological University Department of Civil Engineeringthan zawNo ratings yet

- Statutory Duties and Liabilities of An Engineer in Construction ProjectsDocument39 pagesStatutory Duties and Liabilities of An Engineer in Construction ProjectsIyyer CookNo ratings yet

- The Fidic Short Form of ContractDocument11 pagesThe Fidic Short Form of ContractteedNo ratings yet

- Contracts, Biddings and Tender:Rule of ThumbFrom EverandContracts, Biddings and Tender:Rule of ThumbRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Introduction To GSP Plus Status and Its Impact On Pakistan's EconomyDocument11 pagesIntroduction To GSP Plus Status and Its Impact On Pakistan's Economyfaw03No ratings yet

- Global WarmingDocument28 pagesGlobal Warmingfaw03No ratings yet

- Analysis of The Recent NFC AwardDocument24 pagesAnalysis of The Recent NFC Awardfaw03No ratings yet

- Economic RecoveryDocument17 pagesEconomic Recoveryfaw03No ratings yet

- Currency DevaluationDocument19 pagesCurrency Devaluationfaw03No ratings yet

- Introduction To GSP Plus Status and Its Impact On Pakistan's EconomyDocument11 pagesIntroduction To GSP Plus Status and Its Impact On Pakistan's Economyfaw03No ratings yet

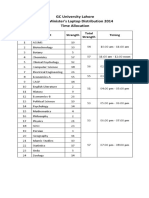

- GC University Lahore Prime Minister's Laptop Distribution 2014 Time AllocationDocument1 pageGC University Lahore Prime Minister's Laptop Distribution 2014 Time Allocationfaw03No ratings yet

- Book Rev. AsentismDocument27 pagesBook Rev. Asentismfaw03No ratings yet

- Soil Investigation Report Plot# 34 Street 14 Sec e PH II PDFDocument14 pagesSoil Investigation Report Plot# 34 Street 14 Sec e PH II PDFfaw03100% (1)

- B. Rev-Making Humour WorkDocument24 pagesB. Rev-Making Humour Workfaw03No ratings yet

- A Food Insecure StateDocument8 pagesA Food Insecure Statefaw03No ratings yet

- Book Rev. Performance Management in A WeekDocument17 pagesBook Rev. Performance Management in A Weekfaw03No ratings yet

- Tourism in Gilgit BaltistanDocument19 pagesTourism in Gilgit Baltistanfaw03100% (1)

- What Is The Difference Between Slag and CementDocument2 pagesWhat Is The Difference Between Slag and Cementfaw03No ratings yet

- D Photo June July 2017Document100 pagesD Photo June July 2017faw03No ratings yet

- E263 PDFDocument10 pagesE263 PDFTin NguyenNo ratings yet

- Advanced Contract Management - ITCILODocument2 pagesAdvanced Contract Management - ITCILOfaw03No ratings yet

- Public-Private Partnership Policies Legal Framework and Competition Requirements 2018Document2 pagesPublic-Private Partnership Policies Legal Framework and Competition Requirements 2018faw03No ratings yet

- Justice Jillani 2Document13 pagesJustice Jillani 2faw03No ratings yet

- Concrete Construction Article PDF - Blast-Furnace Slag As A Mineral Admixture For Concrete PDFDocument3 pagesConcrete Construction Article PDF - Blast-Furnace Slag As A Mineral Admixture For Concrete PDFfaw03No ratings yet

- Works Procurement Management 2018Document2 pagesWorks Procurement Management 2018faw03No ratings yet

- DigitalPhotoGuide Spring2017Document60 pagesDigitalPhotoGuide Spring2017faw03100% (1)

- E-Procurement: Legal Environment Current Solutions, Trends and PoliciesDocument2 pagesE-Procurement: Legal Environment Current Solutions, Trends and Policiesfaw03No ratings yet

- 10 Dispute Resolution in The Pakistani Construction Industry-An Assessment of Current MethodsDocument8 pages10 Dispute Resolution in The Pakistani Construction Industry-An Assessment of Current Methodsfaw03No ratings yet

- Series20 Linking Eia EmsDocument18 pagesSeries20 Linking Eia Emsfaw03No ratings yet

- Class 1c Large BillboardsDocument7 pagesClass 1c Large Billboardsfaw03No ratings yet

- The Fli Bi-GrFr PDFDocument226 pagesThe Fli Bi-GrFr PDFfaw03No ratings yet

- Justice Jillani ADR Speech PDFDocument16 pagesJustice Jillani ADR Speech PDFFirasat Rizwana SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Class 2d Specialised Signs For Parking Areas: SEA 1d, 2a, 2e 2fDocument6 pagesClass 2d Specialised Signs For Parking Areas: SEA 1d, 2a, 2e 2ffaw03No ratings yet

- Class 4c Tourism Direction SignsDocument2 pagesClass 4c Tourism Direction Signsfaw03No ratings yet

- Lateral Pile Paper - Rev01Document6 pagesLateral Pile Paper - Rev01YibinGongNo ratings yet

- BedZED - Beddington Zero Energy Development SuttonDocument36 pagesBedZED - Beddington Zero Energy Development SuttonMaria Laura AlonsoNo ratings yet

- 2023 - Kadam - Review On Nanoparticles - SocioeconomicalDocument9 pages2023 - Kadam - Review On Nanoparticles - Socioeconomicaldba1992No ratings yet

- Icd-10 CM Step by Step Guide SheetDocument12 pagesIcd-10 CM Step by Step Guide SheetEdel DurdallerNo ratings yet

- Cryo CarDocument21 pagesCryo CarAnup PatilNo ratings yet

- El Condor1 Reporte ECP 070506Document2 pagesEl Condor1 Reporte ECP 070506pechan07No ratings yet

- Project Human Resource Management Group PresentationDocument21 pagesProject Human Resource Management Group Presentationjuh1515100% (1)

- Privatization of ExtensionDocument49 pagesPrivatization of ExtensionLiam Tesat67% (3)

- ImpulZ DocumentationDocument9 pagesImpulZ DocumentationexportcompNo ratings yet

- Plewa2016 - Reputation in Higher Education: A Fuzzy Set Analysis of Resource ConfigurationsDocument9 pagesPlewa2016 - Reputation in Higher Education: A Fuzzy Set Analysis of Resource ConfigurationsAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Supplier Relationship Management As A Macro Business ProcessDocument17 pagesSupplier Relationship Management As A Macro Business ProcessABCNo ratings yet

- 100 Free Fonts PDFDocument61 pages100 Free Fonts PDFzackiNo ratings yet

- 5 GR No. 93468 December 29, 1994 NATU Vs TorresDocument9 pages5 GR No. 93468 December 29, 1994 NATU Vs Torresrodolfoverdidajr100% (1)

- Company of Heroes Opposing Fronts Manual PCDocument12 pagesCompany of Heroes Opposing Fronts Manual PCMads JensenNo ratings yet

- April 24, 2008Document80 pagesApril 24, 2008Reynaldo EstomataNo ratings yet

- Ahi Evran Sunum enDocument26 pagesAhi Evran Sunum endenizakbayNo ratings yet

- MEMORIAL ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS DocsDocument29 pagesMEMORIAL ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS DocsPrashant KumarNo ratings yet

- Holiday Activity UploadDocument6 pagesHoliday Activity UploadmiloNo ratings yet

- Special Power of AttorneyDocument1 pageSpecial Power of Attorneywecans izza100% (1)

- Avamar Backup Clients User Guide 19.3Document86 pagesAvamar Backup Clients User Guide 19.3manish.puri.gcpNo ratings yet

- ION Architecture & ION ModulesDocument512 pagesION Architecture & ION ModulesAhmed RabaaNo ratings yet

- March 2023 Complete Month Dawn Opinion With Urdu TranslationDocument361 pagesMarch 2023 Complete Month Dawn Opinion With Urdu Translationsidra shabbirNo ratings yet

- Workflows in RUP PDFDocument9 pagesWorkflows in RUP PDFDurval NetoNo ratings yet

- Application Form ICDFDocument2 pagesApplication Form ICDFmelanie100% (1)

- Complaint - Burhans & Rivera v. State of New York PDFDocument34 pagesComplaint - Burhans & Rivera v. State of New York PDFpospislawNo ratings yet

- Shortcrete PDFDocument4 pagesShortcrete PDFhelloNo ratings yet

- Violence Against NursesDocument22 pagesViolence Against NursesQuality Assurance Officer Total Quality ManagementNo ratings yet

- RBA Catalog Maltby GBR Aug 16 2023 NL NLDocument131 pagesRBA Catalog Maltby GBR Aug 16 2023 NL NLKelvin FaneyteNo ratings yet

- Belimo Fire and Smoke Brochure en UsDocument8 pagesBelimo Fire and Smoke Brochure en UsAmr AbdelsayedNo ratings yet

- Atex ExplainedDocument3 pagesAtex ExplainedErica LindseyNo ratings yet