Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Negotiable Instruments Case List 1

Uploaded by

yassercarlomanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Negotiable Instruments Case List 1

Uploaded by

yassercarlomanCopyright:

Available Formats

NEGOTIABLE

INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

1. Traders Royal Bank Employees Union-Independent vs. NLRC

Emergency Recit:

Lawyer wins case for his client, Traders Royal Bank Employees Union, and asks 10% of awarded fees. Client refuses,

saying he already receives monthly retainer fees. Dispute brought to SC. SC says that Attorneys should be paid for

services rendered over and above Retainer Fees, as the latter is just a fee to secure future services from a lawyer. Even

if no fee is agreed upon, Attorneys should be paid on the basis of quasi-contract (unless there is a clear waiver). The

basis of this amount should be quantam merit, or reasonably based on the amount of work performed.

Facts:

-

Petitioner

Traders

Royal

Bank

Employees

Union

and

private

respondent

Atty.

Emmanuel

Noel

A.

Cruz,

head

of

the

E.N.A.

Cruz

and

Associates

law

firm,

entered

into

a

retainer

agreement

on

February

26,

1987

whereby

the

former

obligated

itself

to

pay

the

latter

a

monthly

retainer

fee

of

P3,000.00

in

consideration

of

the

law

firm's

undertaking

to

render

the

services

enumerated

in

their

contract.

1

The

Union

had

a

case

against

Traders

Royal

Bank

(TRB)

with

the

Labor

Arbiter

over

holiday,

mid

year

and

end-year

bonus

differentials.

Union

was

granted

bonus

differentials.

Decision

was

appealed

to

in

the

SC,

SC

affirmed,

but

only

the

Holiday

bonuses.

The

amount

won

was

Php

175,794.32.

Upon

hearing

this

decision,

lawyer

for

Union

asked

for

10%

of

the

amount

as

lawyers

fees

from

labor

arbiter

and

this

was

granted.

Union

appeals

this

to

the

SC.

They

claim

for

abuse

of

discretion

because

by

awarding

the

lawyer

10%,

they

violated

the

retainer

agreement

found

in

the

engagement

contract

with

the

lawyer,

which

states

that

the

lawyer

gets

Php

3,000

a

month

as

retainer

fee.

Issue:

-

Was

the

Lawyers

filing

for

attorneys

fees

after

the

decision

of

the

SC

was

rendered

valid?

Was

the

Lawyer

entitled

to

attorneys

fees

over

and

above

that

of

the

stated

retainer

fee

in

his

contract?

Held:

WHEREFORE,

the

impugned

resolution

of

respondent

National

Labor

Relations

Commission

affirming

the

order

of

the

labor

arbiter

is

MODIFIED,

and

petitioner

is

hereby

ORDERED

to

pay

the

amount

of

TEN

THOUSAND

PESOS

(P10,000.00)

as

attorney's

fees

to

private

respondent

for

the

latter's

legal

services

rendered

to

the

former.

Ratio:

It

appears

necessary

to

explain

and

consequently

clarify

the

nature

of

the

attorney's

fees

subject

of

this

petition,

in

order

to

dissipate

the

apparent

confusion

between

and

the

conflicting

views

of

the

parties.

There

are

two

commonly

accepted

concepts

of

attorney's

fees,

the

so-called

ordinary

and

extraordinary.

20

In

its

ordinary

concept,

an

attorney's

fee

is

the

reasonable

compensation

paid

to

a

lawyer

by

his

client

for

the

legal

services

he

has

rendered

to

the

latter.

The

basis

of

this

compensation

is

the

fact

of

his

employment

by

and

his

agreement

with

the

client.

In

its

extraordinary

concept,

an

attorney's

fee

is

an

indemnity

for

damages

ordered

by

the

court

to

be

paid

by

the

losing

party

in

a

litigation.

The

basis

of

this

is

any

of

the

cases

provided

by

law

where

such

award

can

be

made,

such

as

those

authorized

in

Article

2208,

Civil

Code,

and

is

payable

not

to

the

lawyer

but

to

the

client,

unless

they

have

agreed

that

the

award

shall

pertain

to

the

lawyer

as

additional

compensation

or

as

part

thereof.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

It is the first type of attorney's fees which private respondent demanded before the labor arbiter. Also, the present

controversy stems from petitioner's apparent misperception that the NLRC has jurisdiction over claims for attorney's

fees only before its judgment is reviewed and ruled upon by the Supreme Court, and that thereafter the former may no

longer entertain claims for attorney's fees. Accordingly, when the labor arbiter ordered the payment of attorney's fees,

he did not in any way modify the judgment of the Supreme Court and is therefore valid.

It is well settled that a claim for attorney's fees may be asserted either in the very action in which the services of a

lawyer had been rendered or in a separate action. 21

It is apparent from the foregoing discussion that a lawyer has two options as to when to file his claim for professional

fees. Hence, private respondent was well within his rights when he made his claim and waited for the finality of the

judgment for holiday pay differential, instead of filing it ahead of the award's complete resolution.

It is elementary that an attorney is entitled to have and receive a just and reasonable compensation for services

performed at the special instance and request of his client. As long as the lawyer was in good faith and honestly trying

to represent and serve the interests of the client, he should have a reasonable compensation for such services. 26 It will

thus be appropriate, at this juncture, to determine if private respondent is entitled to an additional remuneration under

the retainer agreement 27 entered into by him and petitioner.

The difference between a compensation for a commitment to render legal services and a remuneration for legal

services actually rendered can better be appreciated with a discussion of the two kinds of retainer fees a client may pay

his lawyer. These are a general retainer, or a retaining fee, and a special

retainer. 28

A general retainer, or retaining fee, is the fee paid to a lawyer to secure his future services as general counsel for any

ordinary legal problem that may arise in the routinary business of the client and referred to him for legal action. The

future services of the lawyer are secured and committed to the retaining client. For this, the client pays the lawyer a

fixed retainer fee which could be monthly or otherwise, depending upon their arrangement. The fees are paid whether

or not there are cases referred to the lawyer. The reason for the remuneration is that the lawyer is deprived of the

opportunity of rendering services for a fee to the opposing party or other parties. In fine, it is a compensation for lost

opportunities.

A special retainer is a fee for a specific case handled or special service rendered by the lawyer for a client. A client may

have several cases demanding special or individual attention. If for every case there is a separate and independent

contract for attorney's fees, each fee is considered a special retainer.

Hilado vs. David expounds on this concept in this wise:

"A retaining fee is a preliminary fee given to an attorney or counsel to insure and secure his future services, and

induce him to act for the client. It is intended to remunerate counsel for being deprived, by being retained by one

party, of the opportunity of rendering services to the other and of receiving pay from him, and the payment of such

fee, in the absence of an express understanding to the contrary, is neither made nor received in payment of the

services contemplated; its payment has no relation to the obligation of the client to pay his attorney for the services

for which he has retained him to perform."

Evidently, the Php 3,000 retainer fee only covers the law firms pledge, or as expressly stated therein, its commitment

to render the legal services enumerated. The fee is not payment for private respondents execution or performance of

the services listed in the contract, subject to some particular qualifications or permutations stated there.

The fact that petitioner and private respondent failed to reach a meeting of the minds with regard to the payment of

professional fees for special services will not absolve the former of civil liability for the corresponding remuneration

therefor in favor of the latter. The civil liability of the union is one for quasi-contract.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

It is not necessary that the parties agree on a definite fee for the special services rendered by private respondent in

order that petitioner may be obligated to pay compensation to the former. Equity and fair play dictate that petitioner

should pay the same after it accepted, availed itself of, and benefited from private respondent's services.

Viewed from another aspect, since it is claimed that petitioner obtained respondent's legal services and assistance

regarding its claims against the bank, only they did not enter into a special contract regarding the compensation

therefor, there is at least the innominate contract of facio ut des (I do that you may give). 36 This rule of law, likewise

founded on the principle against unjust enrichment, would also warrant payment for the services of private respondent

which proved beneficial to petitioner's members.

Respondent lawyer claims 10% of the awarded bonuses to his client. He bases this on Art. 111 of the Labor Code, stating

that:

Art. 111 Attorneys fees. - in cases of unlawful withholding of wages, the culpable party may be assessed

attorneys fees equivalent to ten percent of the amount of the wages recovered.

However, this cannot apply since this pertains to extraordinary fees, which is in the form of damages, and that is not the

case at hand. Instead, the measure of compensation for private respondent's services as against his client should

properly be addressed by the rule of quantum meruit long adopted in this jurisdiction. Quantum meruit, meaning "as

much as he deserves," is used as the basis for determining the lawyer's professional fees in the absence of a contract, 41

but recoverable by him from his client.

Over the years and through numerous decisions, this Court has laid down guidelines in ascertaining the real worth of a

lawyer's services. These factors are now codified in Rule 20.01, Canon 20 of the Code of Professional Responsibility and

should be considered in fixing a reasonable compensation for services rendered by a lawyer on the basis of quantum

meruit. These are: (a) the time spent and the extent of services rendered or required; (b) the novelty and difficulty of

the questions involved; (c) the importance of the subject matter; (d) the skill demanded; (e) the probability of losing

other employment as a result of acceptance of the proffered case; (f) the customary charges for similar services and the

schedule of fees of the IBP chapter to which the lawyer belongs; (g) the amount involved in the controversy and the

benefits resulting to the client from the services; (h) the contingency or certainty of compensation; (i) the character of

the employment, whether occasional or established; and (j) the professional standing of the lawyer.

It should be this, and not the provision in the Labor Code, that should be used in determining the amount due to the

Lawyer. Based on SCs sound discretion, they place this amount to be at Php 10,000, instead of the Php 17,000+ (10% of

award) asked for by Lawyer.

Summary of Doctrines:

1. Lawyer may ask for fees before or after judgment is rendered.

2. Two kinds of attorneys fees Ordinary (compensation for services) and Extraordinary (for of damages)

3. Two kinds of Retainer fees Ordinary (to secure future services and is considered remuneration for opportunity

costs of the lawyer) and Extraordinary (which is paid on a per case basis)

4. Even if there is no stipulated fee arrangement, lawyer is entitled based on unjust enrichment principle, a form

of quasi contract (unless there is a clear waiver).

5. When there is no basis, Courts will dictate a price based on Quantum meruit, or as much as he deserves.

6. What he deserves, from this case, stems from the Code of Professional Responsibility (posted above).

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

2. Caltex vs. CA and Security Bank

Emergency Recit:

Angel dela Cruz deposited 1,120,000 pesos in Security Bank. In return, he was given 280 certificates of time deposits

(CTDs). These CTDs, despite the trial courts ruling, are made payable to bearer and are thus negotiable instruments.

These CTDs were delivered to Caltexwhich according to it were payments for fuel products. But according to the bank,

and the courts, were merely securities to the eventual payment for the products. Therefore, being that the CTDs were

never negotiated to Caltex, they cannot recover the CTDs. Also, in regards to whether respondent observed the

requirements of the law in the case of lost negotiable instruments and the issuance of replacement certificates, the

Code of Commerce provision is not mandatory and is permissive. It uses the word may. Petition is dismissed, decision

affirmed.

REGALADO, J.:

I. FACTS

On various dates, defendant, a commercial banking institution, through its Sucat Branch issued 280 certificates

of time deposit (CTDs) in favor of one Angel dela Cruz who deposited with herein defendant the aggregate

amount of P1,120,000.00.

Angel dela Cruz delivered the said certificates of time (CTDs) to herein plaintiff in connection with his purchased

of fuel products from the latter.

Sometime in March 1982, Angel dela Cruz informed Mr. Timoteo Tiangco, the Sucat Branch Manger, that he lost

all the certificates of time deposit in dispute. Mr. Tiangco advised said depositor to execute and submit a

notarized Affidavit of Loss, as required by defendant bank's procedure, if he desired replacement of said lost

CTDs

On March 18, 1982, Angel dela Cruz executed and delivered to defendant bank the required Affidavit of Loss.

On the basis of said affidavit of loss, 280 replacement CTDs were issued in favor of said depositor

On March 25, 1982, Angel dela Cruz negotiated and obtained a loan from defendant bank in the amount of

Eight Hundred Seventy Five Thousand Pesos (P875,000.00). On the same date, said depositor executed a

notarized Deed of Assignment of Time Deposit which stated, among others, that de la Cruz surrenders to

defendant bank "full control of the indicated time deposits from and after date" of the assignment and further

authorizes said bank to pre-terminate, set-off and "apply the said time deposits to the payment of whatever

amount or amounts may be due" on the loan upon its maturity.

Sometime in November, 1982, Mr. Aranas, Credit Manager of plaintiff Caltex (Phils.) Inc., went to the defendant

bank's Sucat branch and presented for verification the CTDs declared lost by Angel dela Cruz alleging that the

same were delivered to herein plaintiff "as security for purchases made with Caltex Philippines, Inc." by said

depositor.

On November 26, 1982, defendant received a letter from herein plaintiff formally informing it of its possession

of the CTDs in question and of its decision to pre-terminate the same.

On December 8, 1982, plaintiff was requested by herein defendant to furnish the former "a copy of the

document evidencing the guarantee agreement with Mr. Angel dela Cruz" as well as "the details of Mr. Angel

dela Cruz" obligation against which plaintiff proposed to apply the time deposits. No copy of the requested

documents was furnished herein defendant.

Accordingly, defendant bank rejected the plaintiff's demand and claim for payment of the value of the CTDs in a

letter dated February 7, 1983

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

In April 1983, the loan of Angel dela Cruz with the defendant bank matured and fell due and on August 5, 1983,

the latter set-off and applied the time deposits in question to the payment of the matured loan

In view of the foregoing, plaintiff filed the instant complaint, praying that defendant bank be ordered to pay it

the aggregate value of the certificates of time deposit of P1,120,000.00 plus accrued interest and compounded

interest therein at 16% per annum, moral and exemplary damages as well as attorney's fees.

After trial, the court a quo rendered its decision dismissing the instant complaint & CA affirmed ruling

Issue/Held:

1. that the subject certificates of deposit are non-negotiable despite being clearly negotiable instruments;

a. They are negotiable

2. W/N petitioner can recover the CTDs

a. No

3. The responded erred in disregarding the pertinent provisions of the Code of Commerce relating to lost

instruments payable to bearer.

a. No

Ratio:

SECURITY BANK

AND TRUST COMPANY

6778 Ayala Ave., Makati No. 90101

Metro Manila, Philippines

SUCAT OFFICEP 4,000.00

CERTIFICATE OF DEPOSIT

Rate 16%

Date of Maturity FEB. 23, 1984 FEB 22, 1982, 19____

This is to Certify that B E A R E R has deposited in this Bank the sum of PESOS: FOUR THOUSAND ONLY,

SECURITY BANK SUCAT OFFICE P4,000 & 00 CTS Pesos, Philippine Currency, repayable to said

depositor 731 days. after date, upon presentation and surrender of this certificate, with interest at the

rate of 16% per cent per annum.

(Sgd. Illegible) (Sgd. Illegible)

Respondent court ruled that the CTDs in question are non-negotiable instruments:

o We disagree with these findings and conclusions, and hereby hold that the CTDs in question are

negotiable instruments. The Negotiable Instruments Law, enumerates the requisites for an instrument

to become negotiable. The CTDs in question undoubtedly meet the requirements of the law for

negotiability. The parties' bone of contention is with regard to requisite ((d) Must be payable to order or

to bearer) It is noted that Mr. Timoteo P. Tiangco, Security Bank's Branch Manager way back in 1982,

testified in open court that the depositor referred to in the CTDs is no other than Mr. Angel de la Cruz.

o The accepted rule is that the negotiability or non-negotiability of an instrument is determined from the

writing, that is, from the face of the instrument itself. In the construction of a bill or note, the intention

of the parties is to control, if it can be legally ascertained. The duty of the court in such case is to

ascertain, not what the parties may have secretly intended as contradistinguished from what their

words express, but what is the meaning of the words they have used. What the parties meant must be

determined by what they said.

o The CTDs are negotiable instruments. The documents provide that the amounts deposited shall be

repayable to the depositorwho is the "bearer." The documents do not say that the depositor is Angel

de la Cruz and that the amounts deposited are repayable specifically to him. Rather, the amounts are to

be repayable to the bearer of the documents at the time of presentment.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

If it was really the intention of respondent bank to pay the amount to Angel de la Cruz only, it could

have with facility so expressed that fact in clear and categorical terms in the documents, instead of

having the word "BEARER" stamped on the space provided for the name of the depositor in each CTD.

On the wordings of the documents, therefore, the amounts deposited are repayable to whoever may be

the bearer thereof.

The next query is whether petitioner can rightfully recover on the CTDs. This time, the answer is in the negative.

The records reveal that Angel de la Cruz delivered the CTDs amounting to P1,120,000.00 to petitioner without

informing respondent bank thereof at any time. Unfortunately for petitioner, although the CTDs are bearer

instruments, a valid negotiation thereof for the true purpose and agreement between it and De la Cruz, as

ultimately ascertained, requires both delivery and indorsement. For, although petitioner seeks to deflect this

fact, the CTDs were in reality delivered to it as a security for De la Cruz' purchases of its fuel products. Any doubt

as to whether the CTDs were delivered as payment for the fuel products or as a security has been dissipated and

resolved in favor of the latter by petitioner's own authorized and responsible representative himself.

o Aranas, Jr., Caltex Credit Manager, wrote a letter to the bank admitting the CTDs were merely

guarantees and not the payment for fuel products. Under the doctrine of estoppel, an admission or

representation is rendered conclusive upon the person making it, and cannot be denied or disproved as

against the person relying thereon.

o It has been said that a transfer of property by the debtor to a creditor, even if sufficient on its face to

make an absolute conveyance, should be treated as a pledge if the debt continues in inexistence and is

not discharged by the transfer.

Under the Negotiable Instruments Law, an instrument is negotiated when it is transferred from one person to

another in such a manner as to constitute the transferee the holder thereof, and a holder may be the payee or

indorsee of a bill or note, who is in possession of it, or the bearer thereof.

o In the present case, there was no negotiation in the sense of a transfer of the legal title to the CTDs in

favor of petitioner in which situation, for obvious reasons, mere delivery of the bearer CTDs would have

sufficed. Here, the delivery thereof only as security for the purchases of Angel de la Cruz could at the

most constitute petitioner only as a holder for value by reason of his lien. Accordingly, a negotiation for

such purpose cannot be effected by mere delivery of the instrument since, necessarily, the terms

thereof and the subsequent disposition of such security, in the event of non-payment of the principal

obligation, must be contractually provided for.

o The pertinent law on this point is that where the holder has a lien on the instrument arising from

contract, he is deemed a holder for value to the extent of his lien. As such holder of collateral security,

he would be a pledgee but the requirements therefor and the effects thereof, not being provided for by

the Negotiable Instruments Law, shall be governed by the Civil Code provisions on pledge of incorporeal

rights, which inceptively provide:

Art. 2095. Incorporeal rights, evidenced by negotiable instruments, . . . may also be pledged.

The instrument proving the right pledged shall be delivered to the creditor, and if negotiable,

must be indorsed.

Art. 2096. A pledge shall not take effect against third persons if a description of the thing

pledged and the date of the pledge do not appear in a public instrument.

o Aside from the fact that the CTDs were only delivered but not indorsed, the factual findings of

respondent court quoted at the start of this opinion show that petitioner failed to produce any

document evidencing any contract of pledge or guarantee agreement between it and Angel de la

Cruz. Consequently, the mere delivery of the CTDs did not legally vest in petitioner any right effective

against and binding upon respondent bank. The requirement under Article 2096 aforementioned is not

a mere rule of adjective law prescribing the mode whereby proof may be made of the date of a pledge

o

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

contract,

but

a

rule

of

substantive

law

prescribing

a

condition

without

which

the

execution

of

a

pledge

contract

cannot

affect

third

persons

adversely.

Finally,

petitioner

questions

whether

respondent

observed

the

requirements

of

the

law

in

the

case

of

lost

negotiable

instruments

and

the

issuance

of

replacement

certificates.

o On

this

matter,

we

uphold

respondent

court's

finding

that

the

aspect

of

alleged

negligence

of

private

respondent

was

not

included

in

the

stipulation

of

the

parties

and

in

the

statement

of

issues

submitted

by

them

to

the

trial

court.

Issues

not

raised

in

the

trial

court

cannot

be

raised

for

the

first

time

on

appeal.

o Still,

even

assuming

arguendo

that

said

issue

of

negligence

was

raised

in

the

court

below,

A

close

scrutiny

of

the

provisions

of

the

Code

of

Commerce

laying

down

the

rules

to

be

followed

in

case

of

lost

instruments

payable

to

bearer,

will

reveal

that

said

provisions,

even

assuming

their

applicability

to

the

CTDs

in

the

case

at

bar,

are

merely

permissive

and

not

mandatory.

Art

548.

The

dispossessed

owner,

no

matter

for

what

cause

it

may

be,

may

apply

to

the

judge

or

court

of

competent

jurisdiction,

asking

that

the

principal,

interest

or

dividends

due

or

about

to

become

due,

be

not

paid

a

third

person,

as

well

as

in

order

to

prevent

the

ownership

of

the

instrument

that

a

duplicate

be

issued

him.

(Emphasis

ours.)

o The

use

of

the

word

"may"

in

said

provision

shows

that

it

is

not

mandatory

but

discretionary

on

the

part

of

the

"dispossessed

owner"

to

apply

to

the

judge

or

court

of

competent

jurisdiction

for

the

issuance

of

a

duplicate

of

the

lost

instrument.

o Moreover,

Articles

548

to

558

of

the

Code

of

Commerce,

on

which

petitioner

seeks

to

anchor

respondent

bank's

supposed

negligence,

merely

established

1. a

right

of

recourse

in

favor

of

a

dispossessed

owner

or

holder

of

a

bearer

instrument

so

that

he

may

obtain

a

duplicate

of

the

same,

and,

2.

an

option

in

favor

of

the

party

liable

thereon

who,

for

some

valid

ground,

may

elect

to

refuse

to

issue

a

replacement

of

the

instrument.

Significantly,

none

of

the

provisions

cited

by

petitioner

categorically

restricts

or

prohibits

the

issuance

a

duplicate

or

replacement

instrument

sans

compliance

with

the

procedure

outlined

therein,

and

none

establishes

a

mandatory

precedent

requirement

therefor.

WHEREFORE,

on

the

modified

premises

above

set

forth,

the

petition

is

DENIED

and

the

appealed

decision

is

hereby

AFFIRMED.

SO

ORDERED.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

3. Metropolitan Bank & Trust Company vs. Court of Appeals

Emergency Recit:

Gomez opened an account with Golden Savings Loan Association and deposited 38 treasury warrants worth

P1,755,288.37 drawn by the Philippine Fish Marketing Authority. Golden Savings deposited these warrants in

Metrobank Brank of Calapan to be cleared by the Bureau of Treasury. Because she was persistent in asking them about

the clearance, they just gave in (in other words, nakulitan lang sila). After she withdrew the money and Gomez

subsequently withdrew his money, Metrobank came back to tell them that 32 of the warrants werent cleared by the

Bureau and wanted Golden Savings to pay them back. Went to RTC, judgment in favor of Golden Savings. Court of

Appeals, same judgment. Supreme Court (this case) same judgment. The cause of the dispute was the negligence of

Metrobank. Section 66 of the Negotiable Instruments Law is not applicable to the non-negotiable treasury warrants

because Negotiable Instruments must contain an unconditional promise to pay a sum certain in money (Sec 1) and order

or promise to pay out of a particular fund is not unconditional (Sec 3). the treasury warrants in question are not

negotiable instruments. Clearly stamped on their face is the word "non-negotiable." Moreover, and this is of equal

significance, it is indicated that they are payable from a particular fund, to wit, Fund 501.

CRUZ, J.:

I. FACTS

Metropolitan Bank and Trust Co. commercial bank with branches throughout the Philippines and abroad

Golden Savings and Loan Association operated in Calapan, Mindoro

January 1979 Gomez opened an account with Golden Savings, deposited 38 treasury warrants worth

P1,755,228.37 drawn by the Philippine Fish Marketing Authority

o These warrants were indorsed by Gloria Castillo and deposited to its savings account in the Metrobank

Branch of Calapan

o They were sent for clearing to the principal office of Metrobank which forwarded them to the Bureau of

Treasury for special clearing

Castillo kept going back to Metrobank to ask whether the warrants had been cleared or not. She was told to

wait. Gomez could not withdraw. Later, however, "exasperated" over Gloria's repeated inquiries and also as

an accommodation for a "valued client," the petitioner says it finally decided to allow Golden Savings to

withdraw from the proceeds of the warrants. The total withdrawal was P968.000.00.

Gomez was subsequently allowed to withdraw from his account and collected P1,167,500.00 from the

apparently cleared warrants

July 1979 Metrobank informed Golden Savings that 32 of the warrants had been dishonored by the Bureau of

Treasury and demanded a refund of the amount previously withdrawn.

Metrobank sued Golden Savings in the RTC. Judgment in favor of Golden Savings. On appeal to the Court of

Appeals, the decision was affirmed, prompting Metrobank to file this petition for review.

Issue/Held:

W/N CA erred in disregarding and failing to apply the clear contractual terms and conditions on the deposit slips

allowing Metrobank to charge back any amount erroneously credited.

W/N CA erred in not finding that as between Metrobank and Golden Savings, the latter should bear the loss.

W/N CA erred in holding that the treasury warrants involved in this case are not negotiable instruments.

The Petition has no merit.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

Note: We find the challenged decision to be basically correct. However, we will have to amend it insofar as it directs the

petitioner to credit Golden Savings with the full amount of the treasury checks deposited to its account.

The balance of P586,589.00 should be debited to Golden Savings, as obviously Gomez can no longer be permitted to

withdraw this amount from his deposit because of the dishonor of the warrants. Gomez has in fact disappeared. To also

credit the balance to Golden Savings would unduly enrich it at the expense of Metrobank, let alone the fact that it has

already been informed of the dishonor of the treasury warrants.

Ratio:

From the above undisputed facts, it would appear to the Court that Metrobank was indeed negligent in giving

Golden Savings the impression that the treasury warrants had been cleared and that, consequently, it was safe

to allow Gomez to withdraw the proceeds thereof from his account with it. Without such assurance, Golden

Savings would not have allowed the withdrawals; with such assurance, there was no reason not to allow the

withdrawal.

By contrast, Metrobank exhibited extraordinary carelessness. The amount involved was not trifling more

than one and a half million pesos (and this was 1979). There was no reason why it should not have waited until

the treasury warrants had been cleared; it would not have lost a single centavo by waiting. Yet, despite the lack

of such clearance and notwithstanding that it had not received a single centavo from the proceeds of the

treasury warrants, as it now repeatedly stresses it allowed Golden Savings to withdraw not once, not

twice, but thrice from the uncleared treasury warrants in the total amount of P968,000.00.

The negligence of Metrobank has been sufficiently established. To repeat for emphasis, it was the clearance

given by it that assured Golden Savings it was already safe to allow Gomez to withdraw the proceeds of the

treasury warrants he had deposited Metrobank misled Golden Savings.

o Art. 1909. The agent is responsible not only for fraud, but also for negligence, which shall be judged

'with more or less rigor by the courts, according to whether the agency was or was not for a

compensation.

A no less important consideration is the circumstance that the treasury warrants in question are not negotiable

instruments. Clearly stamped on their face is the word "non-negotiable." Moreover, and this is of equal

significance, it is indicated that they are payable from a particular fund, to wit, Fund 501.

Metrobank cannot contend that by indorsing the warrants in general, Golden Savings assumed that they were

"genuine and in all respects what they purport to be," in accordance with Section 66 of the Negotiable

Instruments Law. The simple reason is that this law is not applicable to the non-negotiable treasury warrants.

The indorsement was made by Gloria Castillo not for the purpose of guaranteeing the genuineness of the

warrants but merely to deposit them with Metrobank for clearing. It was in fact Metrobank that made the

guarantee when it stamped on the back of the warrants: "All prior indorsement and/or lack of endorsements

guaranteed, Metropolitan Bank & Trust Co., Calapan Branch."

PERTINENT PROVISIONS OF NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW

Sec. 1. Form of negotiable instruments. An instrument to be negotiable must conform to the following

requirements:

(a) It must be in writing and signed by the maker or drawer;

(b) Must contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money;

(c) Must be payable on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time;

(d) Must be payable to order or to bearer; and

(e) Where the instrument is addressed to a drawee, he must be named or otherwise indicated therein

with reasonable certainty.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

Sec.

3.

When

promise

is

unconditional.

An

unqualified

order

or

promise

to

pay

is

unconditional

within

the

meaning

of

this

Act

though

coupled

with

(a)

An

indication

of

a

particular

fund

out

of

which

reimbursement

is

to

be

made

or

a

particular

account

to

be

debited

with

the

amount;

or

(b)

A

statement

of

the

transaction

which

gives

rise

to

the

instrument

judgment.

But

an

order

or

promise

to

pay

out

of

a

particular

fund

is

not

unconditional.

Sec.

66.

Liability

of

general

indorser.

-

Every

indorser

who

indorses

without

qualification,

warrants

to

all

subsequent

holders

in

due

course:

(a)

The

matters

and

things

mentioned

in

subdivisions

(a),

(b),

and

(c)

of

the

next

preceding

section;

and

(b)

That

the

instrument

is,

at

the

time

of

his

indorsement,

valid

and

subsisting;

And,

in

addition,

he

engages

that,

on

due

presentment,

it

shall

be

accepted

or

paid,

or

both,

as

the

case

may

be,

according

to

its

tenor,

and

that

if

it

be

dishonored

and

the

necessary

proceedings

on

dishonor

be

duly

taken,

he

will

pay

the

amount

thereof

to

the

holder,

or

to

any

subsequent

indorser

who

may

be

compelled

to

pay

it.

WHEREFORE,

the

challenged

decision

is

AFFIRMED,

with

the

modification

that

Paragraph

3

of

the

dispositive

portion

of

the

judgment

of

the

lower

court

shall

be

reworded

as

follows:

3.

Debiting

Savings

Account

No.

2498

in

the

sum

of

P586,589.00

only

and

thereafter

allowing

defendant

Golden

Savings

&

Loan

Association,

Inc.

to

withdraw

the

amount

outstanding

thereon,

if

any,

after

the

debit.

SO

ORDERED.

Narvasa,

Gancayco,

Grio-Aquino

and

Medialdea,

JJ.,

concur.

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

4. Philippine National Bank vs. Concepcion Mining Co., Inc.

Emergency Recit:

Concepcion Mining Co., Inc. issued a promissory note with Vicente Legarda and Jose Sarte as signatories. Legarda died

on Februaru 24, 1946. Defendants prayed that the estate of the deceased Legarda be included as party-defendant. The

SC held that since the promissory note was executed jointly and severally (solidarily), the payee (PNB) had the right to

hold any of the parties, namely Legarda and Sarte, responsible for the payment of the note.

LABRADOR, J.:

I. FACTS

Appeal from a judgment or decision of the Court of First Instance of Manila. Sentencing defendants Concepcion

Mining Company and Jose Sarte to pay jointly and severally to the plaintiff the amount of P7,197.26 with

interest.

The present action was instituted by the plaintiff to recover from the defendants the face of a promissory note:

o Ninety days after date, for value received, I promise to pay to the order of Philippine National Bank x x

xIn case it is necessary to collect this note by or through an attorney-at-law, the makers and indorsers

shall pay 10% of the amount due on the note as attorneys fees, which in no case shall be less than

P100.00 exclusive of all costs and fees allowed by law as stipulated in the contract of real estate

mortgage. Demand and Dishonor Waived. Holder may accept partial payment reserving his right of

recourse against each and all indorsers. Signed by VICENTE LEGARDA (President), VICENTE LEGARDA,

JOSE S SARTE.

Defendants presented their answer in which they allege that the co-maker of the promissory note Legarda, died

on February 24, 1946 and his estate is in the process of judicial determination in CFI Manila. It is prayed as

special defense, that the estate of said deceased be included as party-defendant.

Motion to reconsider and motion for relief was denied. Hence defendant appealed to the SC.

Issue/Held:

(1) W/N The estate of the deceased Vicente Legarda should be included as party-defendant.

Ratio:

Section 17 of the Negotiable Instruments Law provides:

o Construction where instrument is ambiguous. Where the language of the instrument is ambiguous or

there are omission therein, the following rules of construction apply:

o (g) Where an instrument containing the word I promise to pay is signed by two or more persons, they

are deemed to be jointly and severally liable thereon.

Article 1216 of the Civil Code provides:

o The creditor may proceed against any one of the solidary debtors or some of them simultaneously. The

demand made against one of them shall not be an obstacle to those which may subsequently be

directed against the others as long as the debt has not been fully collected.

In view of these provisions, and as the promissory note was executed jointly and severally by the same parties,

namely, Concepcion Mining Company, Inc. and Vicente Legarda and Jose Sarte, the payee of the promissory

note had the right to hold any one or any two of the signers of the promissory note responsible for the payment

of the amount of the note.

The courts attention has been attracted to the discrepancies on the appeal. (1) The names of the defendants,

NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS CASE LIST 1

who are evidently the Concepcion Mining Co., Inc. and Jose Sarte, do not appear in the printed record on

appeal. (2)The copy of the promissory note which is set forth in the record on appeal does not contain the name

of the third maker Jose Sarte. Evidently, there is an attempt to mislead the court into believing that Jose Sarte is

not one of the co-makers. The attorney for the defendants is Atty. Jose Sarte himself and he should be held

primarily responsible for the correctness of the record on appeal.

You might also like

- Prepared By: Mohammad Muariff S. Balang, CPA, Second Semester, AY 2012-2013Document4 pagesPrepared By: Mohammad Muariff S. Balang, CPA, Second Semester, AY 2012-2013Jayr BV100% (1)

- Rosario vs. de GuzmanDocument3 pagesRosario vs. de Guzmanmiles1280100% (1)

- Radiowealth Finance Corp vs. IACDocument3 pagesRadiowealth Finance Corp vs. IACAnneNo ratings yet

- Contingent Fee Agreement TemplateDocument3 pagesContingent Fee Agreement Templaterapc2010100% (1)

- 4 Types of Salespersons PDFDocument218 pages4 Types of Salespersons PDFStrezo Jovanovski100% (1)

- Cosmopolitan Singapore - July 2013 PDFDocument164 pagesCosmopolitan Singapore - July 2013 PDFdrolfxil100% (2)

- Retainer's AgreementDocument7 pagesRetainer's Agreementaiceljoy100% (1)

- Traders Royal Bank Employees Union v. NLRCDocument2 pagesTraders Royal Bank Employees Union v. NLRCMika AurelioNo ratings yet

- Traders Royal Bank Employees Union v. NLRCDocument2 pagesTraders Royal Bank Employees Union v. NLRCMika AurelioNo ratings yet

- Pale NotesDocument4 pagesPale NotesSUSVILLA IANNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Presentation Canon 20Document13 pagesLegal Ethics Presentation Canon 20Gustavo Fernandez DalenNo ratings yet

- Traders Royal Bank Employees Union v. NLRC, G.R. No. 120592, March 14, 1997, 269 SCRA 733Document5 pagesTraders Royal Bank Employees Union v. NLRC, G.R. No. 120592, March 14, 1997, 269 SCRA 733Gamar AlihNo ratings yet

- Additional Notes For Final ExamsDocument6 pagesAdditional Notes For Final ExamsalexjalecoNo ratings yet

- Traders Royal Bank Employees Union Vs NLRCDocument15 pagesTraders Royal Bank Employees Union Vs NLRCJan BeulahNo ratings yet

- Canon 20 - A Lawyer Shall Charge Only Fair and Reasonable FeesDocument3 pagesCanon 20 - A Lawyer Shall Charge Only Fair and Reasonable FeesMalagant EscuderoNo ratings yet

- Attorney's Fees PALEDocument5 pagesAttorney's Fees PALEerlaine_franciscoNo ratings yet

- Trades Royal VS NLRCDocument2 pagesTrades Royal VS NLRCMaccky RomeNo ratings yet

- Traders Royal Bank Employees Union vs. NLRCDocument11 pagesTraders Royal Bank Employees Union vs. NLRCoscarletharaNo ratings yet

- Legal EthicsDocument7 pagesLegal Ethicsroselleyap20No ratings yet

- PALE - 4. Attorney's Fees and Compensation For Legal ServicesDocument21 pagesPALE - 4. Attorney's Fees and Compensation For Legal ServicesEmmagine E Eyana100% (1)

- @taganas vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 118746, September 7, 1995Document6 pages@taganas vs. NLRC, G.R. No. 118746, September 7, 1995James OcampoNo ratings yet

- LOANZON - VICTORIA - ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN DETERMINING LAW WZTQMBMDocument111 pagesLOANZON - VICTORIA - ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN DETERMINING LAW WZTQMBM'Naif Sampaco PimpingNo ratings yet

- Legal Counselling Midterm ReviewerDocument9 pagesLegal Counselling Midterm ReviewerJen Molo100% (1)

- Legal Ethics Case Digests - Attorney FeesDocument50 pagesLegal Ethics Case Digests - Attorney FeesWilfredo Guerrero IIINo ratings yet

- Research and Services RealtyDocument3 pagesResearch and Services Realtyiris_irisNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in Determining Lawyer'S FeesDocument16 pagesEthical Considerations in Determining Lawyer'S FeesJames Patrick NarcissoNo ratings yet

- TRB EMPLOYEES UNION-INDEPENDENT v. NLRCDocument1 pageTRB EMPLOYEES UNION-INDEPENDENT v. NLRCJennifer OceñaNo ratings yet

- Compensation of Attorney: Basic Legal EthicsDocument110 pagesCompensation of Attorney: Basic Legal EthicsCouleen BicomongNo ratings yet

- Ortiz Vs San Miguel Corp DigestDocument3 pagesOrtiz Vs San Miguel Corp DigestMichael Parreño VillagraciaNo ratings yet

- Sesbreno Vs CADocument7 pagesSesbreno Vs CAShari ThompsonNo ratings yet

- PALE HenryDocument2 pagesPALE HenryDon LongqNo ratings yet

- Advance Legal Ethics CasesDocument9 pagesAdvance Legal Ethics CasesShechem NinoNo ratings yet

- Case Digests (Legal Ethics FINALS Assignment)Document18 pagesCase Digests (Legal Ethics FINALS Assignment)Jether CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Canon 20Document12 pagesCanon 20Pastel Rose CloudNo ratings yet

- 171 Attorney Client Fee ContractDocument3 pages171 Attorney Client Fee ContractcdproductionNo ratings yet

- Traders Royal Bank Employee Union-Independent Vs NLRCDocument1 pageTraders Royal Bank Employee Union-Independent Vs NLRCMaritoni Roxas100% (1)

- Traders Royal Bank Employees Union Vs NLRCDocument1 pageTraders Royal Bank Employees Union Vs NLRCNicole Marie Abella Cortes100% (1)

- @sesbreno vs. CA, G.R. No. 117438, June 8, 1995Document6 pages@sesbreno vs. CA, G.R. No. 117438, June 8, 1995James OcampoNo ratings yet

- PALE Musmud SantiagoDocument10 pagesPALE Musmud SantiagoKathNo ratings yet

- Sesbreno Vs CADocument4 pagesSesbreno Vs CATESDA MIMAROPANo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics - Term Paper WIPDocument22 pagesLegal Ethics - Term Paper WIPJake Floyd G. FabianNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Module 6Document12 pagesLegal Ethics Module 6Nash PungsNo ratings yet

- Aquino v. CasabarDocument2 pagesAquino v. CasabarJulia Alexandra ChuNo ratings yet

- Bach v. Ongkiko Kalaw EthicsDocument11 pagesBach v. Ongkiko Kalaw EthicsG Ant Mgd100% (2)

- Lecture Notes Legal Ethics Part 2Document4 pagesLecture Notes Legal Ethics Part 2Ric TanNo ratings yet

- Barons Marketing V CADocument4 pagesBarons Marketing V CAIrish Garcia100% (1)

- Sesbreno v. CaDocument7 pagesSesbreno v. CaAlyssa Bianca OrbisoNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics - LienDocument6 pagesProfessional Ethics - LienBenjamin Brian Ngonga100% (1)

- Attorney - S Fees - 2020Document40 pagesAttorney - S Fees - 2020Ivan ConradNo ratings yet

- Attorney's FeesDocument34 pagesAttorney's Feesboomblebee100% (1)

- Masmud Vs NLRCDocument4 pagesMasmud Vs NLRCellochoco100% (3)

- GROUP 4 - Torts & Damages Discussion Paper (Attys Fees)Document27 pagesGROUP 4 - Torts & Damages Discussion Paper (Attys Fees)Bhenz Bryle TomilapNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics CasesDocument7 pagesLegal Ethics CasesJermae delos SantosNo ratings yet

- O'Sullivan V Management Agency & Music LTDDocument4 pagesO'Sullivan V Management Agency & Music LTDJoey WongNo ratings yet

- Aquino Vs CasabarDocument10 pagesAquino Vs CasabarJohnde MartinezNo ratings yet

- FT - Taganas vs. NLRCDocument3 pagesFT - Taganas vs. NLRCEdward Garcia LopezNo ratings yet

- PALE - FinalsDocument13 pagesPALE - FinalsJan VelascoNo ratings yet

- Cortes V CADocument3 pagesCortes V CARL N DeiparineNo ratings yet

- PALE - Topic 4 Attorney's FeesDocument36 pagesPALE - Topic 4 Attorney's FeesAnton GabrielNo ratings yet

- 15 Traders Royal Bank Emp Union Vs NLRCDocument19 pages15 Traders Royal Bank Emp Union Vs NLRCmarcel552No ratings yet

- Taganas Vs NLRCDocument2 pagesTaganas Vs NLRCClaudine Christine A VicenteNo ratings yet

- Batch 10 NegoDocument40 pagesBatch 10 NegoJet GarciaNo ratings yet

- Trust Receipts Law (Ampil)Document9 pagesTrust Receipts Law (Ampil)yassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Week 14 NegoDocument13 pagesWeek 14 NegoyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- NEGO Week 12 Documents of Title, General Bonded Warehouse ActDocument9 pagesNEGO Week 12 Documents of Title, General Bonded Warehouse ActyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- NEGO Trust Receipts Law: Emergency RecitDocument8 pagesNEGO Trust Receipts Law: Emergency RecityassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Nego Case List 4: Emergeny RecitDocument24 pagesNego Case List 4: Emergeny RecityassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 20 Puyat & Sons, Inc. vs. Arco Amusement Co.Document8 pages20 Puyat & Sons, Inc. vs. Arco Amusement Co.yassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Lim V CADocument13 pagesLim V CAyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Week 9 NegoDocument18 pagesWeek 9 NegoyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Week 8 Nego PDFDocument13 pagesWeek 8 Nego PDFRay SantosNo ratings yet

- Week 2 Nego PDFDocument29 pagesWeek 2 Nego PDFyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Nego Case List 5 - Sec 60 To 69 Liabilities of PartiesDocument22 pagesNego Case List 5 - Sec 60 To 69 Liabilities of PartiesyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Nego Case List 6 and 7 Sec 70 To 118Document19 pagesNego Case List 6 and 7 Sec 70 To 118yassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Pineda V.De La Rama 121 Scra 671 JedDocument31 pagesPineda V.De La Rama 121 Scra 671 JedyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Lim V CADocument13 pagesLim V CAyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 37 Bordador v. LuzDocument15 pages37 Bordador v. LuzyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Philpotts V Phil ManufacturingDocument5 pagesPhilpotts V Phil ManufacturingyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 20 Puyat & Sons, Inc. vs. Arco Amusement Co.Document8 pages20 Puyat & Sons, Inc. vs. Arco Amusement Co.yassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 07 Rallos V Felx Go Chan & SonsDocument20 pages07 Rallos V Felx Go Chan & SonsyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 08 Dominion Insurance Corp V CADocument10 pages08 Dominion Insurance Corp V CAyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 17 Nielson & Co., Inc V Lepanto Consolidated MiningDocument35 pages17 Nielson & Co., Inc V Lepanto Consolidated MiningyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Ker & Co V LingadDocument10 pagesKer & Co V LingadyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 03 Ereña vs. Querrer-Kauffman PDFDocument25 pages03 Ereña vs. Querrer-Kauffman PDFyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 08 Briones-Vasquez Vs CADocument13 pages08 Briones-Vasquez Vs CAyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 03 Litonjua JR Vs Eternit CorpDocument23 pages03 Litonjua JR Vs Eternit CorpyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 10 DBP vs. Emerald Hotel PDFDocument26 pages10 DBP vs. Emerald Hotel PDFyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 11 Baluyut vs. Poblete PDFDocument19 pages11 Baluyut vs. Poblete PDFyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Case Hamilton Jacobs JPYDocument3 pagesCase Hamilton Jacobs JPYAndré Felipe de MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Case Details SBIDocument7 pagesCase Details SBINiranjan KanadeNo ratings yet

- Contoh Percakapan Handling Check in and ReservationDocument2 pagesContoh Percakapan Handling Check in and ReservationDede SuryansahNo ratings yet

- WP47 Kelton PDFDocument30 pagesWP47 Kelton PDFEugenio MartinezNo ratings yet

- Cash Flows From Operating ActivitiesDocument5 pagesCash Flows From Operating ActivitiesIrfan MansoorNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Employee MotivationDocument72 pagesA Project Report On Employee MotivationNoor Ahmed64% (25)

- Application Form For Bank of Baroda International Debit CardDocument1 pageApplication Form For Bank of Baroda International Debit CardTech ManiacNo ratings yet

- 6 Month Transaction BankDocument15 pages6 Month Transaction BankShravan KumarNo ratings yet

- Customer Management and Organizational Performance of Banking Sector - A Case Study of Commercial Bank of Ethiopia Haramaya Branch and Harar BranchesDocument10 pagesCustomer Management and Organizational Performance of Banking Sector - A Case Study of Commercial Bank of Ethiopia Haramaya Branch and Harar BranchesAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- AlMasraf Newsletter Issue 2Document25 pagesAlMasraf Newsletter Issue 2Vijay WeeJayNo ratings yet

- Bank of Baroda Acquires Local Area Bank LTD: GujaratDocument8 pagesBank of Baroda Acquires Local Area Bank LTD: GujaratAnkush BhoriaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Online Shopping (Final)Document14 pagesIntroduction To Online Shopping (Final)Sahil MalikNo ratings yet

- PNB vs. Reyes - Annulment of REMDocument2 pagesPNB vs. Reyes - Annulment of REMTheodore0176100% (1)

- Intermodal Weekly 16-2013Document8 pagesIntermodal Weekly 16-2013Wisnu KertaningnagoroNo ratings yet

- Ranjit WiproDocument1 pageRanjit WiproHanumanth RaoNo ratings yet

- Sbi Life - Ewealth Insurance Proposal Form: (UIN: 111L100V02)Document12 pagesSbi Life - Ewealth Insurance Proposal Form: (UIN: 111L100V02)shruthiNo ratings yet

- Financing Mining Projects PDFDocument7 pagesFinancing Mining Projects PDFEmil AzhibayevNo ratings yet

- Analyzing and Investing in Community Bank StocksDocument234 pagesAnalyzing and Investing in Community Bank StocksRalphVandenAbbeele100% (1)

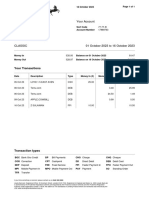

- Statement 2023 10Document1 pageStatement 2023 109jhdh8qthtNo ratings yet

- The Guest Cycle in HotelDocument3 pagesThe Guest Cycle in HotelAnonymous oY0VrepuOMNo ratings yet

- The Bankers' Book Evidence Act, 1891Document4 pagesThe Bankers' Book Evidence Act, 1891Rizwan Niaz RaiyanNo ratings yet

- Final Law Report 1876-1879Document11 pagesFinal Law Report 1876-1879Rae Anne ÜNo ratings yet

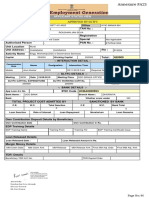

- Forwarded To Bank: Applicant Status ViewDocument4 pagesForwarded To Bank: Applicant Status ViewNANDANI kumariNo ratings yet

- Financial ControlsDocument4 pagesFinancial ControlsDEEPAK GROVERNo ratings yet

- OPMT Group Assignment-3 (Rev2)Document6 pagesOPMT Group Assignment-3 (Rev2)Ahmed H. AldowNo ratings yet

- 6.chapter 4 Research MethodologyDocument6 pages6.chapter 4 Research MethodologySmitha K BNo ratings yet

- Working CapitalDocument72 pagesWorking CapitalSyaapeNo ratings yet