Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nutrition PDF

Uploaded by

Madalina PopescuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nutrition PDF

Uploaded by

Madalina PopescuCopyright:

Available Formats

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

Carol Rees Parrish, R.D., M.S., Series Editor

Elemental and Semi-Elemental

Formulas: Are They Superior to

Polymeric Formulas?

Diklar Makola

Nutritional support, utilizing enteral nutrition formulas, is an integral part of the primary and/or adjunctive management of gastrointestinal and other disorders with

nutritional consequences. Four major types of enteral nutrition formulas exist including: elemental and semi-elemental, standard or polymeric, disease-specific and

immune-enhancing. Although they are much more expensive, elemental and semielemental formulas are purported to be superior to polymeric or standard formulas in

certain patient populations. The aim of this article is to evaluate whether this claim is

supported by the literature and to ultimately show that except for a very few indications, polymeric formulas are just as effective as elemental formulas in the majority of

patients with gastrointestinal disorders.

INTRODUCTION

he provision of nutritional support is an essential

part of the primary and adjunctive management of

many gastrointestinal (GI) disorders such as

Crohns disease, cystic fibrosis, pancreatitis, head and

neck cancer, cerebrovascular accidents, etc. Nutritional

support can be used to induce remission in Crohns dis-

Diklar Makola, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D., Gastroenterology

Fellow, University of Virginia Health System, Digestive

Health Center of Excellence, Charlottesville, VA.

ease, facilitate pancreatic rest in pancreatitis and prevent nutritional depletion that accompanies many GI

tract diseases. The factors leading to nutritional depletion include: 1) impaired absorption of nutrients;

2) inadequate intake due to anorexia; 3) dietary restrictions; 4) increased intestinal losses; and 5) an increase in

nutritional demand that accompanies many catabolic

states. Nutritional support can be provided by using

either total parenteral nutrition (PN) or total enteral

nutrition (EN), however EN when compared to PN has

fewer serious complications (1,2) and is less expensive

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

59

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

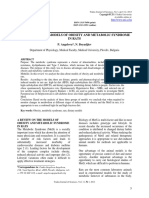

Table 1

Cost Comparison of Elemental and Standard Formulas

Product

Company

Cost $/1000 kcal*+

Elemental /Semi-elemental

AlitraQ (E)

f.a.a. (E)

Optimental (SE)

Peptamen (SE)

Peptamen 1.5 (SE)

Peptinex (SE)

Peptinex DT (SE)

Perative (SE)

Subdue (SE)

Subdue Plus (SE)

Tolerex (E)

Vital HN (SE)

Vivonex T.E.N. (E)

Vivonex Plus (E)

Ross

Nestle

Ross

Nestle

Nestle

Novartis

Novartis

Ross

Novartis

Novartis

Novartis

Ross

Novartis

Novartis

Product

Company

Cost $/1000 kcal*+

Standard, Polymeric

29.17

28.00

24.30

24.06

24.22

21.60

18.58

8.68

19.79

13.19

16.70

20.28

18.33

31.30

Fibersource HN

Isocal

Isosource 1.5

Jevity 1.0

Jevity 1.5

Novasource 2.0

Nutren 1.5

Nutren 2.0

Osmolite 1.0

Osmolite 1.2

Probalance

Promote

Replete

TwoCal HN

Novartis

Novartis

Novartis

Ross

Ross

Novartis

Nestle

Nestle

Ross

Ross

Nestle

Ross

Nestle

Ross

3.73

7.60

4.44

6.60

6.60

3.04

3.72

2.99

6.94

6.08

6.84

6.60

7.35

3.21

Ross Consumer Relations

1-800-227-5767

MondayFriday 8:30 A.M.65:00 P.M. EST

www.ross.com

Nestl InfoLink Product and Nutrition Information Services

1-800-422-2752

Pricing: 1-877-463-7853

Monday Friday 8:30 A.M.65 P.M. CST

www.nestleclinicalnutrition.com

Novartis Medical Nutrition Consumer and Product Support

1-800-333-3785 (choose Option 3)

MondayFriday 9:00 A.M.6:00 P.M. EST

http://www.novartisnutrition.com/us/home

*Except for Nestle products, price does not include shipping and handling; +Per 800# on 11/7/05; E = elemental;

SE = Semi-elemental; Note: Lipisorb, Criticare HN and Reabilan are no longer available; Used with permission from

the University of Virginia Health System Nutrition Support Traineeship Syllabus (Parrish 05)

than PN. The EN formulas differ in their protein and fat

content and can be classified as elemental (monomeric),

semi-elemental (oligomeric), polymeric or specialized.

Elemental formulas contain individual amino acids, glucose polymers, and are low fat with only about 2% to 3%

of calories derived from long chain triglycerides (LCT)

(3). Semi-elemental formulas contain peptides of vary60

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

ing chain length, simple sugars, glucose polymers or

starch and fat, primarily as medium chain triglycerides

(MCT) (3). Polymeric formulas contain intact proteins,

complex carbohydrates and mainly LCTs (3). Specialized formulas contain biologically active substances or

nutrients such as glutamine, arginine, nucleotides or

(continued on page 62)

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

(continued from page 60)

essential fatty acids (Table 1). Although elemental and

semi-elemental formulas cost about 400% more than

polymeric formulas (4) they are still widely used because

they are believed to be 1) better absorbed, 2) less allergenic, 3) better tolerated in patients with malabsorptive

states and 4) cause less exocrine pancreatic stimulation

in patients with pancreatitis.

The aim of this paper is to evaluate whether there

is evidence to support the superiority of elemental

and/or semi-elemental formulas over polymeric formulas in providing nutritional support in patients with

gastrointestinal diseases.

THEORETICAL BENEFITS OF ELEMENTAL

AND SEMI-ELEMENTAL FORMULAS

of water and electrolytes. However, as will be discussed

in subsequent sections, semi-elemental, as well as elemental, formulas have not been demonstrated to be

superior to polymeric formulas (811).

Steinhardt, et al (10) found that although nitrogen

absorption was better in total pancreatectomized

patients who received hydrolyzed lactalbumin (semielemental formula) when compared to those who

received intact lactalbumin (polymeric formula), nitrogen balance was similar between the two formula

groups. The similarity in nitrogen balance between the

two groups was most likely due to the significantly

higher urea production in the hydrolyzed formula

group. Of note, the patients in this study were not

given pancreatic enzymes, the standard of practice in

pancreatectomized patients.

Elemental (Monomeric) Formulas

Elemental formulas contain individual amino acids,

are low in fat, especially LCTs, and as such, are

thought to require minimal digestive function and

cause less stimulation of exocrine pancreatic secretion.

In many products, MCT is the predominant fat source,

and can be absorbed directly across the small intestinal

mucosa into the portal vein in the absence of lipase or

bile salts; they are believed to be beneficial in malabsorptive states. They are also considered to be advantageous in patients with acute pancreatitis (3), and in

those with other malabsorptive states (5).

Semi-elemental (Oligomeric) Formulas

The nitrogen source of semi-elemental formulas are

proteins that have been hydrolyzed into oligopeptides of

varying lengths, dipeptides and tripeptides. The di- and

tripeptides of semi-elemental formulas have specific

uptake transport mechanisms and are thought to be

absorbed more efficiently than individual amino acids

or whole proteins, the nitrogen sources in elemental and

polymeric formulas respectively (6). Silk, et al (7) found

that individual and free amino acid residues, as found in

elemental formulas, were poorly absorbed while amino

acids provided as dipeptides and tripeptides were better

absorbed. The semi-elemental formulas containing

casein and lactalbumin hydrolysates, but not the fish

protein hydrolysates, also stimulated jejunal absorption

62

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

COMPARISON OF ELEMENTAL AND/OR

SEMI-ELEMENTAL TO POLYMERIC FORMULAS

BY PATIENT/STUDY POPULATION

Malabsorptive States

It is often assumed that most, if not all, patients with

GI problems have varying levels of malabsorption

and/or maldigestion and would therefore benefit from

elemental or semi-elemental formulas. Malabsorption

occurs as a result of a defect in the transportation of

nutrients across the mucosa in conditions such as

Crohns, celiac disease or radiation enteritis, and only

reaches clinical significance when 90% of organ function is impaired (12,13). On the other hand, maldigestion is due to intra-luminal defects of absorption such

as pancreatic insufficiency, bile salt deficiency and

bacterial overgrowth (14). Some of these digestive

defects can be corrected by providing digestive

enzymes or treating with antibiotics (12).

Patients considered to have malabsorption in the

EN literature include patients who 1) have normal or

moderately impaired gastrointestinal tract function, 2)

are critically ill in the intensive care unit, 3) have undergone abdominal surgery or bowel resection or 4) have

variations of the above who develop diarrhea after the

start of EN. Most of these studies do not document the

evidence and extent of malabsorption and/or maldigestion. In addition, many of these studies have not found

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

a significant difference in nutrient absorption and balance (8,1517). Rees, et al (16) found that only a subgroup of 3 patients with extensive small bowel mucosal

defects had noticeably better nitrogen absorption and

balance when fed with a semi-elemental diet.

Short Bowel Syndrome

Patients with short bowel syndrome (SBS) tend to be

considered ideal candidates for elemental and semi-elemental formulas because of the malabsorption associated

with SBS and the theoretical benefit of more efficient

absorption. However, studies aimed at comparing the

efficacy of elemental and semi-elemental formulas to

polymeric formulas in patients with SBS have resulted in

conflicting results. McIntyre, et al (9) found no difference in nitrogen or total calorie absorption between a

semi-elemental and polymeric liquid formula in patients

with <150 cm of jejunum ending in jejunostomy. In contrast, Cosnes, et al (11), found greater nitrogen absorption with consumption of a peptide based (semi-elemental) diet when compared to a whole protein (polymeric)

diet in a similar group of patients. However, Cosnes, et

al also found greater blood urea nitrogen and urea nitrogen excretion during feeding with the peptide-based diet

than during whole protein feeding, suggesting that the

additional absorption of amino acids resulted in an

increase in amino acid oxidation. It is not known whether

the increase in nitrogen absorption improved protein

metabolism or nitrogen balance because these parameters were not measured (5).

In a more recent randomized crossover trial conducted in children with SBS, Ksiazyk, et al (18) found

no significant difference in intestinal permeability,

energy, and nitrogen balance when diets with

hydrolyzed protein were compared to those with nonhydrolyzed protein. There is insufficient evidence to

suggest that the more expensive elemental or semi-elemental formulas are superior to polymeric formulas in

patients with SBS (19).

Hypoalbuminemia

Elemental and semi-elemental diets are purported to be

beneficial in improving tolerance to EN and reduce the

development of diarrhea when given to patients with

hypoalbuminemia. This assumption was based on case

series reports by Brinson that seemed to suggest that

these formulas resulted in increased nitrogen absorption

and reduced stool output when given to hypoalbuminemic patients (20,21). However, a randomized clinical

trial aimed at comparing a peptide based enteral formula

with a standard formula concluded that the peptide formula offered no advantage to the standard formula (22).

Studies by Viall and Heimburger (23,24) also found that

semi-elemental compared to standard polymeric EN

was equally well tolerated and resulted in similar digestive or mechanical complicationssuch as diarrhea,

vomiting and high gastric residuals. The nitrogen balance was similar with both formulas in the Viall (23)

study while Heimburger, et al (24) found that the peptide formula resulted in a slightly greater increase in

serum rapid-synthesis proteins such as the surrogate

markers, prealbumin and fibronectin, especially

between days 5 and 10. However, prealbumin levels are

also affected by other disease-related factors such as

infection, cytokine response, renal and liver failure and

do not necessarily reflect nutritional status (19) thus

making the significance of this finding unclear.

Crohns Disease

Enteral nutrition is effective in inducing remission in

patients with uncomplicated, active Crohns disease

(2528). Meta-analyses of EN versus corticosteroids

have found that although corticosteroids are superior

to EN in inducing remission (2931), EN is also efficacious with expected remission rates of up to 60% on

an intention to treat basis (25,29,30).

The Effect of Enteral Nutrition Protein

on Crohns Disease Remission

Elemental formulas are thought to induce remission in

Crohns disease patients by providing chemically synthesized amino acids that are entirely antigen free thus

limiting the patients exposure to dietary antigens that

may precipitate or exacerbate a Crohns flare. Giaffer,

et al (32) found a significantly higher clinical remission rate (based on reduction in Chronic Disease

Activity Index (CDAI) scores) after 10 days of an elemental formula (Vivonex), compared to a polymeric

formula (Fortison), 75% versus 36% respectively.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

63

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

However these findings have not been replicated in

other studies (3335). Rigaud, et al found no significant difference in clinical remission rates based on

CDAI scores measured during the last 7 days of a 28

day period between Crohns disease patients treated

with elemental (Vivonex HN) versus polymeric EN

(Realmentyl or Nutrison) (35). The remission rates

were 66% in the elemental group and 73% in the polymeric group. The CDAI seemed to improve more

rapidly in the elemental group with a remission rate of

60% achieved by day 14; however, the difference in

remission rates at day 14 was not statistically significant. Verma, et al also found that although clinical

remission seemed to occur earlier in the elemental

group, time to remission was not statistically different

(34). Ludvigsson, et al found that 16 children with

Crohns disease who received an elemental (Elemental

028 Extra) versus 17 who received a polymeric (Nutrison Standard), had similar remission rates (69% versus

82%) (33). Patients treated with the polymeric formula

gained more weight even after controlling for maximum caloric intake per kilogram of body weight.

Two meta-analyses based on clinical trials that

compared elemental to non-elemental or polymeric formulas found no significant difference in clinical remission rates among patients managed with the different

formulas (29,31). These results suggest that elemental

formulas are not superior to non-elemental or polymeric formulas in inducing remission and that avoiding

dietary protein in the formula is unlikely to be the

mechanism by which EN induces Crohns remission.

The Effect of Enteral Nutrition Fat on

Crohns Disease Remission

Some researchers have hypothesized that the beneficial

effect of EN on Crohns remission may be due to the fat

content of the formula. It has been suggested that n-6

polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as linoleic

acid, a precursor of arachidonic acid, leads to increased

production of inflammatory eicosanoids such as

prostaglandin E2, thromboxane A2 and leukotriene B4,

which may be detrimental in Crohns disease (36);

while n-3 PUFAs such as -linolenic acid, precursors

of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexanoic acid

which lead to the production of the less inflammatory

series-3 prostaglandins and leukotiene B5 (36), may be

64

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

protective. Increased amounts of n-3 PUFAs also

inhibit arachidonic acid production thus reducing the

production of the pro-inflammatory eicosanoids (36).

To test the hypothesis that altering fat content may

prove beneficial in Crohns, Bamba, et al (37) randomly

allocated 28 patients to low fat, medium fat and high fat

elemental diets containing 3.06, 16.56, and 30.06 g/day

of fat. The 3 formulas had identical total calories, nitrogen source, vitamins and minerals but differed in their fat

and carbohydrate content. The remission rates after 4

weeks of treatment were 80%, 40% and 25% respectively, thus favoring the low-fat group. The extra fat in

the medium and high fat groups was made up of long

chain triglycerides and contained 52% linoleic, 24%

oleic and 8% linolenic acid. Bamba, et al (37) concluded

that the high fat content in elemental formulas consisting

mainly of n-6 PUFAs or long chain triglycerides (LCT)

decreased the therapeutic effect of enteral formulas.

Leiper, et al (38) compared a low LCT to a high

LCT polymeric EN. The low LCT provided 5% of

energy as LCT with MCT providing 30%. The high

LCT provided 30% of energy with MCT providing 5%

energy. The linoleic acid content was similar between

the two formulas (7.4% versus 9.5%), but the high

LCT contained 36% of oleic acid compared to 3.4% in

the low LCT group. The formulas were identical in

color, carbohydrate, total fat, minerals, trace elements

and vitamin levels. Overall remission rates were unexpectedly low in both groups with no significant difference between the two formulas, (low LCT 33% versus

high LCT 52%) thus making it difficult to compare the

efficacy of the two formulas in this study (36). The

poor responses were unlikely to be due to the effect of

linoleic acid content in the enteral formula since both

formulas had low concentrations of linoleic acid.

Gassull, et al (39) compared polymeric formulas

containing either high oleate (79% oleate, 6.5%

linoleate) or low oleate (28% oleate, 45% linoleate)

content. The total LCT and MCT were similar in the

two groups. A third group was randomly allocated to

oral prednisone (1 mg/kg daily). Contrary to expectations, the high oleate/low linoleate group, which was

expected to have higher remission rates, had significantly lower remission rates when compared to both

the low oleate/higher linoleate and steroid groups

(continued on page 69)

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

(continued from page 64)

(20% versus 52% and 79%). The authors concluded

that excess synthetic oleate may be responsible for the

low remission rates seen in the high oleate/low

linoleate group (39).

Sakurai, et al (40) found no significant difference in

remission rates in Crohns patients when a low fat elemental formula (3.4 g per 2000 kcal dose) was compared

to a protein hydrosylate, high fat formula (55.6 g fat per

2000 kcal dose) (67% in the low fat elemental formula

group and 72% in the high fat semi-elemental formula

group). Most of the fat in the high fat group came from

MCT. They concluded that it is not necessary to restrict

the MCT content of enteral formulas (40). Based on

Bamba, et als (37) study in which the high fat group did

poorly, and based on the theoretical disadvantage of

LCT, especially linoleic acid, Gorard, et al (36) argue

that high LCT and /or linoleic acid in enteral formulas

may attenuate the effect of EN in inducing Crohns disease remission. Based on Gasull, et als study excess

synthetic oleate may also be detrimental (39).

Cystic Fibrosis

Maintaining good nutritional status, though often difficult to achieve, is positively correlated with a good

prognosis and survival in patients with cystic fibrosis

(CF). Several studies have shown that long-term nocturnal EN supplementation in patients with cystic fibrosis helps maintain nutrition and slows down the decline

in pulmonary function. It is now recommended that CF

patients whose weight for height is less than 85% of

ideal, and who fail to respond to a 3-month trial of noninvasive nutritional interventions, should receive EN

(41). However, CF centers differ in their recommendations on the type of enteral formula and the use of pancreatic enzymes in patients requiring EN.

In an cross-over trial comparing Peptamen (semielemental formula) and Isocal (polymeric formula)

with pancreatic enzymes added in 4 to 20 year-oldpatients with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency, Erksine, et al (4) found no significant difference in fat and nitrogen absorption or in weight gain

between the two groups. Pelekanos, et al (42) also

found no significant difference in rates of protein synthesis and catabolism among patients managed with

Criticare HN (semi-elemental), Traumacal (polymeric)

and Modified Traumacal (modified polymeric with

less protein and fat when compared to Traumacal) formulas. Because there are no studies that demonstrate

the superiority of elemental or semi-elemental over

polymeric formulas, using the less expensive polymeric formula supplemented with pancreatic enzyme

supplements would be more cost-effective (43).

Acute Pancreatitis

Historically, PN has been the standard method of nutritional support in patients with severe acute pancreatitis.

The use of PN was aimed at avoiding exocrine pancreatic stimulation and providing pancreatic rest while

providing nutrition to the patient (1). However, recent

data suggests that EN delivered distal to the Ligament of

Treitz is well tolerated, results in fewer infectious complications, and is less expensive than PN (1,2,4447).

Most EN studies in this patient population have utilized

the more expensive elemental formulas, in the belief

that they do not require pancreatic stimulation for

absorption and are therefore least likely to stimulate the

pancreas (43,48). However, jejunal polymeric EN is

also well tolerated by patients with acute pancreatitis

and can potentially be used to facilitate pancreatic rest

(46,47,49,50). Furthermore, because of concerns that

the increased fat content or intact proteins in polymeric

formulas will cause increased pancreatic stimulation

and slow the resolution of pancreatitis (2,51), clinicians

still prefer to use elemental or semi-elemental jejunal

formulas in patients with acute pancreatitis. However,

polymeric formulas have also been successfully used in

long-term enteral nutrition in patients with chronic pancreatitis (43,52). No studies have compared elemental or

semi-elemental formulas to polymeric formulas in

patients with acute pancreatitis.

Radiation Related GI Tract Damage

Elemental and semi-elemental formulas have also been

tried in patients with gastrointestinal problems related to

pelvic and abdominal radiotherapy. In a review of studies involving 2,646 patients who underwent radiotherapy for gynecologic, urologic and rectal cancer in the

UK, the authors noted that 50% of patients developed

chronic bowel symptoms and 11%33% developed

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

69

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

(continued from page 68)

malnutrition requiring some form of nutritional management (53). These studies all varied in design and

validity, none of which could be combined into a metaanalysis since the interventions and outcomes were different. The nutritional interventions were implemented

either during or after completion of radiation therapy

and included low fat diets, low residue diets, elemental

diets versus modified or polymeric diets or parenteral

nutrition, lactose free and gluten free diets, as well as

use of probiotics and micronutrient supplements. Three

of the studies included in the above review found that

elemental diets reduced the incidence and severity of

diarrhea symptoms. However the largest of these 3

papers674 patientswas only published as an

abstract in a non-peer reviewed summary booklet. The

authors concluded that there was no evidence to suggest

that nutritional interventions could prevent or manage

bowel symptoms attributable to radiotherapy, but that

low-fat diets, probiotic supplementation and elemental

diets merited further investigation.

HIV Related Disease

Nutritional trials conducted in HIV positive patients

have tested either 1) specialized, immune-enhancing

supplements/formulas in which a polymeric formula is

fortified with omega 3 fatty acids and or arginine versus non-fortified formulas (54,55); 2) elemental versus

polymeric formulas (5658) and 3) nutritional counseling plus usual diet versus nutritional counseling plus

usual diet and nutritional supplementation (59,60).

Pichard, et al found that arginine and omega 3 fatty

acid enriched formulas did not improve immunological

parameters when compared to a non-enriched formula

with similar amounts of calories and protein. Both

groups experienced a similar significant weight gain. In

contrast to these findings, Suttman, et al (54) in a

crossover double-blind trial in which a polymeric formula fortified with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid and

arginine was compared to a polymeric non-fortified formula, found that the enriched formula resulted in significant weight gain and an increase in soluble tumor

necrosis factor receptor proteins, thus theoretically

modulating the negative effects of tumor necrosis factor.

In the studies by Rabeneck, et al and Schwenk, et al

nutritional counseling, rather than nutritional supple70

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

mentation, resulted in an overall improvement in nutritional intake and nutritional outcomes (59,60). Gibert, et

al found no significant difference in percent weight

change and body cell mass after 4 months of supplementation with a peptide based formula when compared

to a whole protein based formula (57). Similarly, Hoh, et

al (58) found no significant difference in gastrointestinal

symptoms, body weight and free fat mass between HIV

patients supplemented for 6 weeks with a whole proteinbased compared to those supplemented with a peptidebased formula (58). De Luis Roman (56) found that 3

month supplementation with a peptide based, n-3 fatty

acid enriched formula resulted in a significant increase in

CD4 counts when compared to supplementation with a

non-enriched, standard and whole protein based formula.

Both formulas resulted in a significant and sustained

increase in fat mass weight while there was no change in

fat free mass and total body water (56).

Finally, Micke, et al compared two different types

of whey protein based formulas and found that after

two weeks of supplementation both supplements

resulted in a significant increase in glutathione levels

(61). These studies suggest that elemental and semielemental formulas are not superior to polymeric formulas in improving the nutritional status of patients

with HIV, but that there may be some evidence of an

immunologic benefit, with or without a nutritional

benefit, when specialized formulas enriched with n-3

fatty acids are compared to non-enriched formulas.

Chyle Leak

Most of the nutritional recommendations in managing

patients with chyle leak are based on case series and

theoretical considerations. A more extensive review of

this subject appears in the May 2004 edition of Practical Gastroenterology (62). The objective of nutritional

management is to reduce chyle fluid production by

eliminating LCT from the diet, replace fluid and electrolytes while providing adequate nutrition to maintain

nutritional status, correct deficiencies or prevent malnutrition. For those patients who are able to tolerate

food by mouth, a fat-free diet given with MCT, fatsoluble vitamins and essential fatty acid (EFA) supplements should be attempted. However, for those patients

who require EN, a very low fat elemental, MCT-based

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

formula should be used. These formulas typically provide an adequate amount of EFA and fat-soluble vitamins. Alternatively, (for short-term trial only), a more

economical option would be to use a fat-free liquid

nutritional supplement combined with a multivitamin/mineral supplement, a fat free protein supplement

and small amount of safflower oil to provide EFA.

CONCLUSION

There is no evidence to suggest that elemental and/or

semi-elemental formulas are superior to polymeric formulas when used to provide nutritional support and

treatment in patients with most gastrointestinal diseases

that are likely to cause maldigestion and malabsorption.

In patients with maldigestion, it may indeed be less

expensive to treat the underlying problem such as pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease or small bowel bacterial overgrowth, with digestive enzymes, a gluten free

diet/formula or an antibiotic respectively, rather than

use an expensive elemental formula. The mechanism

by which enteral feedings achieve remission in Crohns

disease is still not well understood and needs further

research. Specialized or immune-enhancing formulas

(fortified with n-3 fatty acids) may be beneficial in

enhancing immunity, but not necessarily the nutritional

status, of patients with HIV when compared to non-fortified formulas. Although randomized trials of elemental and polymeric EN in the management of patients

with pancreatitis are lacking, EN using a polymeric formula administered beyond the Ligament of Trietz may

be as effective, as well as safer, than PN. Elemental

and semi-elemental formulas, for the most part, should

be reserved for those patients who have failed a fair

trial of several polymeric formulas before considering

the parenteral route.

References

1. Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Meta-analysis of parenteral nutrition versus

enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. BMJ,

2004;328(7453):1407.

2. Abou-Assi S, Craig K, OKeefe SJ. Hypocaloric jejunal feeding is

better than total parenteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis: results of

a randomized comparative study. Am J Gastroenterol, 2002;

97(9):2255-2262.

3. Chen QP. Enteral nutrition and acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol, 2001;7(2):185-192.

4. Erskine JM, Lingard CD, Sontag MK, et al. Enteral nutrition for

patients with cystic fibrosis: comparison of a semi-elemental and

nonelemental formula. J Pediatr, 1998; 132(2):265-269.

5. Klein S Rubin D, C. Enteral and parenteral nutrition. In: Feldman M,

Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Eds. Sleisenger & Fordtrans gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002:2 v. (xli, 2385, 98 ).

6. Farrell JJ. Digestion and absorption of nutrients and vitamins. In:

Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Eds. Sleisenger &

Fordtrans gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology,

diagnosis, management. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002:2 v.

(xli, 2385, 98 ).

7. Silk DB, Fairclough PD, Clark ML, et al. Use of a peptide rather

than free amino acid nitrogen source in chemically defined elemental diets. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1980;4(6):548-553.

8. Ford EG, Hull SF, Jennings LM, et al. Clinical comparison of tolerance to elemental or polymeric enteral feedings in the postoperative patient. J Am Coll Nutr, 1992;11(1):11-16.

9. McIntyre PB, Fitchew M, Lennard-Jones JE. Patients with a high

jejunostomy do not need a special diet. Gastroenterology,

1986;91(1):25-33.

10. Steinhardt HJ, Wolf A, Jakober B, et al. Nitrogen absorption in

pancreatectomized patients: protein versus protein hydrolysate as

substrate. J Lab Clin Med, 1989;113(2): 162-167.

11. Cosnes J, Evard D, Beaugerie L, et al. Improvement in protein

absorption with a small-peptide-based diet in patients with high

jejunostomy. Nutrition, 1992;8(6):406-411.

12. Romano TJ, Dobbins JW. Evaluation of the patient with suspected

malabsorption. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 1989;18(3):

467-483.

13. Silk DB, Grimble GK. Relevance of physiology of nutrient absorption to formulation of enteral diets. Nutrition, 1992;8(1):1-12.

14. Hogenauer C, Hammer HF. Maldigestion and malabsorption. In:

Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Eds. Sleisenger &

Fordtrans gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology,

diagnosis, management. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002:2 v.

(xli, 2385, 98 ).

15. Jones BJ, Lees R, Andrews J, et al. Comparison of an elemental

and polymeric enteral diet in patients with normal gastrointestinal

function. Gut, 1983;24(1):78-84.

16. Rees RG, Hare WR, Grimble GK, et al. Do patients with moderately impaired gastrointestinal function requiring enteral nutrition

need a predigested nitrogen source? A prospective crossover controlled clinical trial. Gut, 1992;33(7):877-881.

17. Dietscher JE, Foulks CJ, Smith RW. Nutritional response of

patients in an intensive care unit to an elemental formula vs a standard enteral formula. J Am Diet Assoc, 1998;98(3): 335-336.

18. Ksiazyk J, Piena M, Kierkus J, et al. Hydrolyzed versus nonhydrolyzed protein diet in short bowel syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2002;35(5):615-618.

19. Klein S, Jeejeebhoy KN. The malnourished patient: nutritional

assessment and management. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS,

Sleisenger MH, Eds. Sleisenger & Fordtrans gastrointestinal and

liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. 7th ed.

Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002:2 v. (xli, 2385, 98).

20. Brinson RR, Kolts BE. Diarrhea associated with severe hypoalbuminemia: a comparison of a peptide-based chemically defined diet

and standard enteral alimentation. Crit Care Med, 1988;16(2):130136.

21. Brinson RR, Curtis WD, Singh M. Diarrhea in the intensive care

unit: the role of hypoalbuminemia and the response to a chemically

defined diet (case reports and review of the literature). J Am Coll

Nutr, 1987;6(6):517-523.

22. Mowatt-Larssen CA, Brown RO, Wojtysiak SL, et al. Comparison

of tolerance and nutritional outcome between a peptide and a standard enteral formula in critically ill, hypoalbuminemic patients.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1992;16(1):20-24.

23. Viall C, Porcelli K, Teran JC, et al. A double-blind clinical trial

comparing the gastrointestinal side effects of two enteral feeding

formulas. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1990;14(3):265-269.

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

71

Elemental, Semi-Elemental and Polymeric Formulas

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #34

24. Heimburger DC, Geels VJ, Bilbrey J, et al. Effects of small-peptide and whole-protein enteral feedings on serum proteins and diarrhea in critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JPEN J Parenter

Enteral Nutr, 1997;21(3):162-167.

25. Griffiths AM. Enteral nutrition in the management of Crohns disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2005;29(4 Suppl):S108-S117.

26. OSullivan MA, OMorain CA. Nutritional therapy in Crohns disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 1998;4(1):45-53.

27. OSullivan M, OMorain C. Nutritional Treatments in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol, 2001;

4(3):207-213.

28. OSullivan M, OMorain C. Nutritional Therapy in Inflammatory

Bowel Disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol, 2004;7(3):

191-198.

29. Griffiths AM, Ohlsson A, Sherman PM, et al. Meta-analysis of

enteral nutrition as a primary treatment of active Crohns disease.

Gastroenterology, 1995;108(4):1056-1067.

30. Fernandez-Banares F, Cabre E, Esteve-Comas M, et al. How effective is enteral nutrition in inducing clinical remission in active

Crohns disease? A meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials.

JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1995;19(5):356-364.

31. Zachos M, Tondeur M, Griffiths AM. Enteral nutritional therapy

for inducing remission of Crohns disease. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev, 2001(3):CD000542.

32. Giaffer MH, North G, Holdsworth CD. Controlled trial of polymeric versus elemental diet in treatment of active Crohns disease.

Lancet, 1990;335(8693):816-819.

33. Ludvigsson JF, Krantz M, Bodin L, et al. Elemental versus polymeric enteral nutrition in paediatric Crohns disease: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Acta Paediatr, 2004; 93(3):327335.

34. Verma S, Brown S, Kirkwood B, et al. Polymeric versus elemental

diet as primary treatment in active Crohns disease: a randomized,

double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol, 2000;95(3):735-739.

35. Rigaud D, Cosnes J, Le Quintrec Y, et al. Controlled trial comparing

two types of enteral nutrition in treatment of active Crohns disease:

elemental versus polymeric diet. Gut, 1991; 32(12):1492-1497.

36. Gorard DA. Enteral nutrition in Crohns disease: fat in the formula.

Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2003;15(2):115-118.

37. Bamba T, Shimoyama T, Sasaki M, et al. Dietary fat attenuates the

benefits of an elemental diet in active Crohns disease: a randomized,

controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2003;15(2):151-157.

38. Leiper K, Woolner J, Mullan MM, et al. A randomised controlled

trial of high versus low long chain triglyceride whole protein feed

in active Crohns disease. Gut, 2001;49(6):790-794.

39. Gassull MA, Fernandez-Banares F, Cabre E, et al. Fat composition

may be a clue to explain the primary therapeutic effect of enteral

nutrition in Crohns disease: results of a double blind randomised

multicentre European trial. Gut, 2002;51(2):164-168.

40. Sakurai T, Matsui T, Yao T, et al. Short-term efficacy of enteral

nutrition in the treatment of active Crohns disease: a randomized,

controlled trial comparing nutrient formulas. JPEN J Parenter

Enteral Nutr, 2002;26(2):98-103.

41. Ramsey BW, Farrell PM, Pencharz P. Nutritional assessment and

management in cystic fibrosis: a consensus report. The Consensus

Committee. Am J Clin Nutr, 1992;55(1):108-116.

42. Pelekanos JT, Holt TL, Ward LC, et al. Protein turnover in malnourished patients with cystic fibrosis: effects of elemental and

nonelemental nutritional supplements. J Pediatr Gastroenterol

Nutr, 1990;10(3):339-343.

43. Yoder AJ. Nutrition Support in Pancreatitis: Beyond Parenteral

Nutrition. Practical Gastroenterology, 2003:19-30.

44. Kalfarentzos F, Kehagias J, Mead N, et al. Enteral nutrition is superior to parenteral nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis: results of a

randomized prospective trial. Br J Surg, 1997;84(12):1665-1669.

72

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY DECEMBER 2005

45. McClave SA, Greene LM, Snider HL, et al. Comparison of the

safety of early enteral vs parenteral nutrition in mild acute pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1997;21(1): 14-20.

46. Windsor AC, Kanwar S, Li AG, et al. Compared with parenteral

nutrition, enteral feeding attenuates the acute phase response and

improves disease severity in acute pancreatitis. Gut, 1998;42(3):

431-435.

47. Pupelis G, Selga G, Austrums E, et al. Jejunal feeding, even when

instituted late, improves outcomes in patients with severe pancreatitis and peritonitis. Nutrition, 2001;17(2):91-94.

48. Erstad BL. Enteral nutrition support in acute pancreatitis. Ann

Pharmacother, 2000;34(4): 514-521.

49. Powell JJ, Murchison JT, Fearon KC, et al. Randomized controlled

trial of the effect of early enteral nutrition on markers of the inflammatory response in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg,

2000;87(10):1375-1381.

50. Yoder A, Parrish C, Yeaton P. A retrospective review of the course

of patients with pancreatitis discharged on jejunal feedings. NCP,

2002;17:314-320.

51. OKeefe SJ, Lee RB, Anderson FP, et al. Physiological effects of

enteral and parenteral feeding on pancreaticobiliary secretion in

humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2003;

284(1):G27-G36.

52. Stanga Z, Giger U, Marx A, et al. Effect of jejunal long-term feeding in chronic pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr,

2005;29(1):12-20.

53. McGough C, Baldwin C, Frost G, Andreyev HJ. Role of nutritional

intervention in patients treated with radiotherapy for pelvic malignancy. Br J Cancer, 2004;90(12):2278-2287.

54. Suttmann U, Ockenga J, Schneider H, et al. Weight gain and

increased concentrations of receptor proteins for tumor necrosis

factor after patients with symptomatic HIV infection received fortified nutrition support. J Am Diet Assoc, 1996;96(6):565-569.

55. Pichard C, Sudre P, Karsegard V, et al. A randomized double-blind

controlled study of 6 months of oral nutritional supplementation

with arginine and omega-3 fatty acids in HIV-infected patients.

Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Aids, 1998;12(1):53-63.

56. de Luis Roman DA, Bachiller P, Izaola O, et al. Nutritional treatment

for acquired immunodeficiency virus infection using an enterotropic

peptide-based formula enriched with n-3 fatty acids: a randomized

prospective trial. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2001;55(12):1048-1052.

57. Gibert CL, Wheeler DA, Collins G, et al. Randomized, controlled

trial of caloric supplements in HIV infection. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. J Acquir Immune

Defic Syndr, 1999;22(3):253-259.

58. Hoh R, Pelfini A, Neese RA, et al. De novo lipogenesis predicts

short-term body-composition response by bioelectrical impedance

analysis to oral nutritional supplements in HIV-associated wasting.

Am J Clin Nutr, 1998;68(1):154-163.

59. Rabeneck L, Palmer A, Knowles JB, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating nutrition counseling with or without oral

supplementation in malnourished HIV-infected patients. J Am Diet

Assoc, 1998;98(4):434-438.

60. Schwenk A, Steuck H, Kremer G. Oral supplements as adjunctive

treatment to nutritional counseling in malnourished HIV-infected

patients: randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr, 1999;18(6):371-374.

61. Micke P, Beeh KM, Schlaak JF, et al. Oral supplementation with

whey proteins increases plasma glutathione levels of HIV-infected

patients. Eur J Clin Invest, 2001;31(2):171-178.

62. McCray S, Parrish C. When chyle leaks: nutrition management

options. Practical Gastroenterology, 2004; 28(5):60-76.

63. Parrish CR, Krenitsky J, McCray S. University of Virginia Health

System Nutrition Support Traineeship Syllabus, 2003. Available

at: http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/dietitian/dh/

traineeship.cfm.

You might also like

- Nutrition and Functional Foods in Boosting Digestion, Metabolism and Immune HealthFrom EverandNutrition and Functional Foods in Boosting Digestion, Metabolism and Immune HealthNo ratings yet

- MakolaArticle Dec 05 PDFDocument9 pagesMakolaArticle Dec 05 PDFRahmaniaNo ratings yet

- Protein Digestion Absorption NASPGHANDocument4 pagesProtein Digestion Absorption NASPGHANDahiru MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Nutritional SciencesDocument4 pagesRecent Advances in Nutritional SciencesVlad PopaNo ratings yet

- BY Nelson Munthali Dip/RNDocument56 pagesBY Nelson Munthali Dip/RNArmySapphireNo ratings yet

- Is It Possible To Increase Weight and Maintain The Protein Status of Debilitated Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes?Document10 pagesIs It Possible To Increase Weight and Maintain The Protein Status of Debilitated Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes?Han BurhanNo ratings yet

- Rni ChoDocument10 pagesRni ChoAimi HannaniNo ratings yet

- Campbell 2006Document9 pagesCampbell 2006Sílvia TrindadeNo ratings yet

- 1475 2891 2 9 PDFDocument5 pages1475 2891 2 9 PDFTufail ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Functional Foods in Boosting Digestion Metabolism and Immune Health Debasis Bagchi Download PDF ChapterDocument51 pagesNutrition and Functional Foods in Boosting Digestion Metabolism and Immune Health Debasis Bagchi Download PDF Chapterstephanie.priest452100% (6)

- Metabolic and Physiologic Effects From Consuming A Hunter-Gatherer (Paleolithic) - Type Diet in Type 2 DiabetesDocument6 pagesMetabolic and Physiologic Effects From Consuming A Hunter-Gatherer (Paleolithic) - Type Diet in Type 2 DiabetesJavi Vergara VidalNo ratings yet

- Diet As Adjunctive Treatment For Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Review and Update of The Latest LiteratureDocument13 pagesDiet As Adjunctive Treatment For Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Review and Update of The Latest LiteratureNejc KovačNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument4 pagesNutritionRaquel M. MendozaNo ratings yet

- RTD Otsuka Parenteral NutritionDocument39 pagesRTD Otsuka Parenteral NutritionMuhammad IqbalNo ratings yet

- Resveratrol Sindrome Metabolica e DisbioseDocument29 pagesResveratrol Sindrome Metabolica e DisbioseRodrigo De Oliveira ReisNo ratings yet

- Publish 1Document8 pagesPublish 1Mark PengNo ratings yet

- TPNDocument69 pagesTPNMylz MendozaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 3 MalnutritionDocument21 pagesCase Study 3 Malnutritionrohayatjohn100% (3)

- Lesson Preview: Calculating Diets and Meal PlanningDocument5 pagesLesson Preview: Calculating Diets and Meal PlanningKristinelou Marie N. ReynaNo ratings yet

- Feeding FormulaesDocument4 pagesFeeding FormulaesG.sri DakshayaniNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Nutritional Feeding Strategies in Pediatric Intestinal FailureDocument14 pagesNutrients: Nutritional Feeding Strategies in Pediatric Intestinal FailureKatherin AmadoNo ratings yet

- Enteral NutritionDocument62 pagesEnteral Nutritionrkdivya100% (1)

- Novel Insights On Nutrient Management of Sarcopenia in ElderlyDocument15 pagesNovel Insights On Nutrient Management of Sarcopenia in ElderlyMario Ociel MoyaNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Diet TherapyDocument3 pagesNutrition and Diet TherapyNalee Paras Beños100% (1)

- GastroparesisDocument10 pagesGastroparesisapi-437831510No ratings yet

- Crawford Nutri Sas 19Document14 pagesCrawford Nutri Sas 19Divo Skye CrawfordNo ratings yet

- Diare 1Document9 pagesDiare 1Altus GoldenNo ratings yet

- Fat Malabsorption in Critical IllnessDocument6 pagesFat Malabsorption in Critical Illnesslakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Biodisponibilidad de Vitamina EDocument14 pagesBiodisponibilidad de Vitamina EJonathan Francisco Rojas CarvajalNo ratings yet

- The Gastrointestinal RADocument3 pagesThe Gastrointestinal RAAisha SaherNo ratings yet

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Colonic Function: Roles of Resistant Starch and Nonstarch PolysaccharidesDocument34 pagesShort-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Colonic Function: Roles of Resistant Starch and Nonstarch Polysaccharidesbdalcin5512No ratings yet

- MFN-005 Unit-4 PDFDocument17 pagesMFN-005 Unit-4 PDFShubhendu ChattopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Dietary Fiber, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument11 pagesNutrients: Dietary Fiber, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Diseasemichael palitNo ratings yet

- Eslinger, Ajetal YellowPeaFiber NutritionResearch20 (2014)Document9 pagesEslinger, Ajetal YellowPeaFiber NutritionResearch20 (2014)mgipsohnNo ratings yet

- Angelova 2013 Review Models of Obesity and Metabolic SyndromeDocument8 pagesAngelova 2013 Review Models of Obesity and Metabolic SyndromePaul SimononNo ratings yet

- Chung S.Yang (2008) - Bioavailability Issues in Studying The Health Efects of Plant Polyphenolic CompoundsDocument13 pagesChung S.Yang (2008) - Bioavailability Issues in Studying The Health Efects of Plant Polyphenolic CompoundsthanhktNo ratings yet

- Fenugreek As Dietary FibreDocument4 pagesFenugreek As Dietary FibrePriyadarshini Mh100% (2)

- Research Open Access: Antonio Paoli, Lorenzo Cenci and Keith A GrimaldiDocument8 pagesResearch Open Access: Antonio Paoli, Lorenzo Cenci and Keith A Grimaldipainah sumodiharjoNo ratings yet

- Dietary and Medical Management of ShortDocument9 pagesDietary and Medical Management of ShortNelly ChacónNo ratings yet

- Case 3 QuestionsDocument8 pagesCase 3 Questionsapi-532124328No ratings yet

- Nutrition in The Critically Ill PatientDocument13 pagesNutrition in The Critically Ill PatientnainazahraNo ratings yet

- CHORIBar HistoryDocument9 pagesCHORIBar HistoryK Mehmet ŞensoyNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Vegetable-Based Diets For Chronic Kidney Disease? It Is Time To ReconsiderDocument26 pagesNutrients: Vegetable-Based Diets For Chronic Kidney Disease? It Is Time To ReconsidervhnswrNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Support of The Critically Ill Small AnDocument12 pagesNutritional Support of The Critically Ill Small AnTactvisNo ratings yet

- Meeting Basic Needs - Nutrition Sept 2021Document61 pagesMeeting Basic Needs - Nutrition Sept 2021ashley nicholeNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Dietary Pattern: Chap-5Document41 pagesNutrition and Dietary Pattern: Chap-5Imad AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Parenteral Nutrition: Uses, Indications, and Compounding: Compendium (Yardley, PA) March 2007Document10 pagesParenteral Nutrition: Uses, Indications, and Compounding: Compendium (Yardley, PA) March 2007Ricardo Diaz NiñoNo ratings yet

- Role of Nutrition in The Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy in End-Stage Liver Failure - PMCDocument1 pageRole of Nutrition in The Management of Hepatic Encephalopathy in End-Stage Liver Failure - PMCgladieNo ratings yet

- Nutrition 1Document5 pagesNutrition 1Christine PunsalanNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument46 pagesNutritionKeren Karunya SingamNo ratings yet

- FALL 2021 N41A Basic Nutrition TherapyDocument44 pagesFALL 2021 N41A Basic Nutrition TherapyheliNo ratings yet

- D Evander Schue Ren 2019Document3 pagesD Evander Schue Ren 2019Joseneide Custódio RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Managing The Adult Patient With Short Bowel SyndromeDocument18 pagesManaging The Adult Patient With Short Bowel SyndromeGar BettaNo ratings yet

- PDF Document 5Document28 pagesPDF Document 5Kirstin del CarmenNo ratings yet

- Enteral Nutrition: Sanja KolačekDocument5 pagesEnteral Nutrition: Sanja KolačekManuela MontesNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrates and Fiber, Lunn 2007Document44 pagesCarbohydrates and Fiber, Lunn 2007Gladys LunaNo ratings yet

- Estradiol Determine Liver Lipid Deposition in Ratsfed Standard Diets Unbalanced With Excess Lipid or ProteinDocument20 pagesEstradiol Determine Liver Lipid Deposition in Ratsfed Standard Diets Unbalanced With Excess Lipid or ProteinIoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Diet EvaluationDocument23 pagesNutrition and Diet EvaluationgabrielwerneckNo ratings yet

- Overview of Vitamin EDocument15 pagesOverview of Vitamin EJames Cojab SacalNo ratings yet

- 2.2 Polyamide and Polyester Fibers. Comprehensive Composite Materials, HU, X.-C., & YANG, H. H. (2000) .Document18 pages2.2 Polyamide and Polyester Fibers. Comprehensive Composite Materials, HU, X.-C., & YANG, H. H. (2000) .Ponsyo PonsiNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Ethylene OxideDocument7 pagesExecutive Summary: Ethylene OxideBlueblurrr100% (1)

- Organic Reaction MechanismDocument15 pagesOrganic Reaction Mechanismrohit13339No ratings yet

- Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of Aliphatic Primary Nitrosamines Stabilized by Coordination To (IrCl5) 2Document11 pagesSynthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of Aliphatic Primary Nitrosamines Stabilized by Coordination To (IrCl5) 2Benjamín Marc Ridgway de SassouNo ratings yet

- Bio Ethanol Production From MolassesDocument24 pagesBio Ethanol Production From MolassesVivek VetalNo ratings yet

- D2789Document7 pagesD2789rimi7alNo ratings yet

- TDS (FD)Document2 pagesTDS (FD)Yash RaoNo ratings yet

- CHM138 - Tutorial QuestionsDocument20 pagesCHM138 - Tutorial Questions2022643922No ratings yet

- A Descriptive Report On The Industrial Affairs at The Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research OrganizationDocument29 pagesA Descriptive Report On The Industrial Affairs at The Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organizationanyango ninaNo ratings yet

- Science Adh8615Document13 pagesScience Adh8615bobzlzhuNo ratings yet

- Lipids ProteinsDocument5 pagesLipids ProteinsRuchie Ann Pono BaraquilNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas Conversion GuideDocument52 pagesNatural Gas Conversion GuidehonabbieNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Oxidised Diterpenoid Acids Using Methylation With TMAHDocument17 pagesAnalysis of Oxidised Diterpenoid Acids Using Methylation With TMAHjgNo ratings yet

- Orgo 1 QuzzesDocument34 pagesOrgo 1 QuzzesDanny NguyenNo ratings yet

- Varian GC Column CatalogueDocument79 pagesVarian GC Column Cataloguehadi002No ratings yet

- 18 01 23 - Dok Bak-Isotank13 Lm13 & Isotank14 Lm14Document6 pages18 01 23 - Dok Bak-Isotank13 Lm13 & Isotank14 Lm14Jay Van BuurninkNo ratings yet

- Olive Oil As A Functional FoodDocument19 pagesOlive Oil As A Functional FoodRadwan Ajo100% (1)

- Hempel Hempandur 15553 MsdsDocument13 pagesHempel Hempandur 15553 MsdsM.FAIZAN ARSHADNo ratings yet

- PhotosynthesisDocument52 pagesPhotosynthesisAdelaide CNo ratings yet

- Bio IaDocument15 pagesBio IaBoom YummyNo ratings yet

- CarbonDocument121 pagesCarbonggNo ratings yet

- DisplayArticleForFree 1Document4 pagesDisplayArticleForFree 1ctza88No ratings yet

- Organic Chemistry (Conceptual Questions)Document31 pagesOrganic Chemistry (Conceptual Questions)Vanshika MauryaNo ratings yet

- Inorganic and Organic ChemistryDocument8 pagesInorganic and Organic ChemistryValerie BorrioNo ratings yet

- Hdpe Guide PDFDocument81 pagesHdpe Guide PDFbalotNo ratings yet

- Liquid Crystal Polymers WikipediaDocument3 pagesLiquid Crystal Polymers WikipediasheetalNo ratings yet

- Molecular Weight Characterization and Rheology of Lignins For Carbon Fiber-ProiectDocument190 pagesMolecular Weight Characterization and Rheology of Lignins For Carbon Fiber-ProiectKate RyncaNo ratings yet

- Ashima Results in ChemistryDocument13 pagesAshima Results in ChemistryPrachi PatnaikNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 2 Carbonyl CompoundsDocument12 pagesTutorial 2 Carbonyl Compounds2022834672No ratings yet

- Chemical Formulae, Equations, Calculations 1 MS PDFDocument8 pagesChemical Formulae, Equations, Calculations 1 MS PDFNewton JohnNo ratings yet

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (36)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Summary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietFrom EverandSummary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeFrom EverandThe Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- I Shouldn't Feel This Way: Name What’s Hard, Tame Your Guilt, and Transform Self-Sabotage into Brave ActionFrom EverandI Shouldn't Feel This Way: Name What’s Hard, Tame Your Guilt, and Transform Self-Sabotage into Brave ActionNo ratings yet

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (267)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (254)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- How to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingFrom EverandHow to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Summary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (61)