Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory

Uploaded by

salomonmarinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory

Uploaded by

salomonmarinaCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [190.189.217.

131]

On: 29 April 2014, At: 09:29

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwap20

Holy terrors: Latin American women perform

Diana Taylor

a b

& Roselyn Costantino

Professor and Chair of Performance Studies , NYU

Director of the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics

Associate Professor of Spanish and Women's Studies , Penn State University

Published online: 03 Jun 2008.

To cite this article: Diana Taylor & Roselyn Costantino (2000) Holy terrors: Latin American women perform, Women &

Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 11:2, 7-24, DOI: 10.1080/07407700008571329

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07407700008571329

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and

should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for

any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of

the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION

HOLY TERRORS:

LATIN AMERICAN WOMEN PERFORM

Diana Taylor and Roselyn Costantino

his volume brings together a divergent group of women

artists involved in some of the most important aesthetic and

political movements of Latin America.1 In one sense, these

women don't have a lot in common: Diana Raznovich (1945), a feminist playwright and cartoonist from Argentina, descended from

Russian Jews who fled the pogroms at the turn of the 19 century

and boarded the wrong boat (they thought they were going to the

United States). Griselda Gambaro (1928), Argentina's most widely

recognized playwright, is of Italian origin. Denise Stoklos (1950),

author, director, and Brazil's most important solo performer, comes

from the south of Brazil, and is of Ukrainian extraction. Astrid

Hadad (1957), performer, singer, director, and manager of her show,

born in the southern Mexican state of Quintana Roo, is of Lebanese

heritage. Jesusa Rodriguez (1955), director, actor, playwright,

scenographer, entrepreneur, and feminist activist, is of Mexican

indigenous and European ancestry. Sabina Berman (1955), playwright, director, poet, novelist, and film scriptwriter), is of Polish

Jewish extraction. El teatro de la mascara (the Theatre of the Mask),

Women (S Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, Issue 22,11:2

2000 Women & Performance Project, Inc.

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

8 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

a woman's collective from Cali, Colombia, which started in the early

1970s, includes women of diverse ethnic origins. Tania Brugera

(1968) is a Cuban performer who explores the long history of extermination and political repression through her work.

These backgrounds attest to the racial and ethnic diversity of

Latin America, and make visible a complicated history of Spanish

and Portuguese colonialization, mestizaje, slavery, migration, U.S.

imperialism, and political exile. There are many reasonscultural,

economic, political, militarywhy these women are "Latin American." All of themwhether from the highlands of Chiapas or the

far reaches of Europeundergo profound processes of identity

(re)formation by participating in the "imagined community" of

Latin America. For some, the process began hundreds of years ago

when pre-Conquest ethnic identities came into uneasy contact with

European colonial systems. Colonialism and 19* and 20 t n century

nationalism have tried to erase all ethnic categories and relegate

"Indians," as an undifferentiated mass of marginalized peoples, to

a forgotten past. Authors and activists fight to give native peoples

their rightful place in the here and now of a heterogeneous "Latin

America." For groups whose population spreads out over different

countries, ethnic identity does not necessarily dovetail with national

identity. Tania Brugera, to posit a radically different example of the

same phenomenon, envisions a "greater Cuba" that spans both sides

of the Caribbean ocean. For Puerto Ricans, the struggle has been to

define themselves as "Puerto Rican" and, by extension, Latin American, rather than accept a colonial status as a second-class citizen of

the United States.2 Puerto Ricans, who endure the ambiguous status

of U.S. colonial subjects, are often missing from the Latin American political and geographic map. For others, the identification with

Latin America involved exile and migration from the poverty or

terrors of their countries of origins. For each, "Latin American"

proves more a negotiated political, ethnic, and cultural positioning

than a genetic or racial identitythat is, a political, rather than biological, matrix.

For each, moreover, "Latin America" proves quite differentfor

some, it consists of huge metropolitan centers like Mexico City, Sao

Paulo or Buenos Aires. For others, it's the indigenous communities

in the highlands of Chiapas or the Andes. If the differences and

divergences prove so great, and if the term "Latin America" does

not have a clear explanatory power, to what degree does the term

provide a useful framework for discussion?

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTIONS

"Amerique Latine," like "America," are European constructionsthe first coined in mid-191" century France to refer to countries in the Americas colonized by Spain and Portugal, the second

in honor of Italian explorer, Amerigo Vespucci, who first argued that

the newly "discovered" Iandmass was not, in fact, Asia. There is no

general consensus about how many countries make up Latin

America: does Puerto Rico count as a country or as a U.S. "commonwealth"? Does the term include French speaking countries such

as Haiti and Martinique (usually), or English-speaking or Dutchspeaking countries such as Trinidad or Surinam (often not)?

Nonetheless, for all the problems with the term, it does have some

virtues for Latin Americans themselves. In the 19 tn century, Simon

Bolivar labored to unite Latin America under one political banner,

convinced that only by uniting could these countries defend themselves from external political and economic pressures. At the end of

the 19 l " century, Jose Marti wrote "Nuestra America" (Our

America) to urge Latin Americans to wake up and get to know each

other before the giant from the North with the big boots crashed

down among them. The current economic treaty among nations in

the southern cone, MERCOSUR, basically echoes the belief that

political and economic independence lies in unity.

For all the disparities of ethnic background, class, and racial privilege, these women share certain histories of social engagement that

allow us to think about them as "Latin American" artists. If geopolitical identity has less to do with "essence" than with conditions of

(im)possibility, then it becomes easier to see how these artists tackle

systems of power that date back to colonial times: Church domination, political oligarchy and dictatorship, and the pervasive sexism

and racism encoded in everything from education to "scientific"

eugenics efforts, to theories of mestizaje and progress. Each, in her

own way, uses performance as a means of making a political intervention in a socio-political context that is repressive when not

overtly violent. Some make their political intervention through

writingwhether it's a manifesto, a cartoon, or a play. Others participate in embodied performances that signal a break from accepted

practice by forming a feminist collective, building an installation,

or abandoning one's traditional dress.

These artists have grown up and worked in periods of extreme

social disruptionwhether it was Argentina's "Dirty War" (197683), or the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964-1984), or the

decades of civil conflict and criminal violence in Colombia, or the

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

10 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

divided Cuba that resulted from Castro's revolution, or the 1968

massacre atTlatelolco and the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City.

While female artists and activists have played a pivotal role in

human rights and social justice movements in Latin Americawe

need only think of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo or Rigoberta

Menchiithe very limited conditions of possibility for women have

dictated that their strategies of intervention were always predetermined by their sex. The Mothers could only intervene as mothers

(see Taylor 1997). Rigoberta Menchu insists in her writings that she

wielded the same power and authority as her male counterparts, only

to reveal again and again that she was able to gain authority in spite

of the fact that she is a woman. Female activists had to fight not only

the "enemy" but the men in their movements as well. Diana

Raznovich (like many artists) returned to Argentina from selfimposed exile to participate in the Teatro abierto movement. Teatro

abierto brought together hundreds of artists who had been blacklisted during the military dictatorship to stage a repertoire of 21

short plays in defiance of the governmental prohibition. Still, even

within this "open" liberatory movement, Diana Raznovich was

chided for being "frivolous." How could her play, El desconcierto,

which depicted a female pianist who tried in vain to wrestle sound

out of a silent piano, have anything to say about the culture of silencing associated with the "Dirty War?" She was asked by her male colleagues to withdraw her contribution to the event. Denise Stoklos,

though a highly acclaimed and paid artist, works at the periphery of

the theatrical establishment. Her solo performances and authored

texts get little more than a passing reference in histories and

overviews of contemporary Brazilian theatre. Astrid Hadad has generated such controversy and disdain from the establishment that

some male practitioners threatened to withdraw from events that

feature her work. El teatro de la mascara in Colombia has been in

existence longer than most collective theatre groups. Nonetheless,

it remains virtually unknown because, the members claim, people

simply don't care about "women's issues." Jesusa Rodriguez, a legendary artist in Mexico's artistic and intellectual communities, survives on their margins. And so it goes for most of these women.

For these women artists, then, political intervention (in the broadest sense) takes on many forms and many fronts including national

and ethnic political movements, human rights activism, and struggles around issues of gender, sexual, and racial equality. Often, in

these struggles, they come up against the Catholic Church. Since

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION 11

the implementation of the "Holy Inquisition" in the 16*" century,

the Catholic Church has sided with civil authorities in the repression of disenfranchized groupsJews, native Americans, African

Americans, and, of course, women. During the "Dirty War,"

Catholic priests blessed the military's weapons with holy water and

turned in "subversives" who revealed their dissidence during confession. The Church continues to meddle with issues pertaining to

women. The Vatican has ruled against birth control, divorce, and

equal opportunity and access for women in a number of areas. It

opposed the Platform for Equal Rights for Women presented at 1995

Fourth World Conference on Women at Beijing and has continued

to try to dismantle the gains made in the fields of reproductive rights,

civil liberties, and education. As women working in deeply

entrenched Catholic societies, these women have become "holy

terrors," taking on not only the authorities, but the systems of belief

that demand that they behave like obedient, subservient creatures.

These artists need to work on many levels simultaneously in their

fight for cultural participation: access to space, to resources, to

authority, and to audienceslocal, national, and international. Most

of these artists have forged their own spacephysical and/or professionalto stage their aesthetic and political acts of resistance.

Some clearly needed to find their own ways of working, having been

closed out or pushed out of existing groups or organizations.

Jesusa Rodriguez and her partner Liliana Felipe, an Argentine

musician, singer and performer started their first cabaret/performance space, El cuervo (the Crow), in 1980 and then El habito (the

Habit) cabaret and El Teatro de la Capilla (the Chapel Theatre) in

1990. Rodriguez, like Astrid Hadad, began training at the Center for

University Theatre of Mexico's National Autonomous University

one of Latin America's major centers for the production and promotion of world-class theatre. Like Hadad, she was repulsed by the

male-run and artistically-limited and limiting nature of Mexico's

theatre and cultural institutions. Both left before finishing the

program and moved into the margins to work independently. (As an

a aside, to explain how women were treated by the male directors,

all well known and still active today, both Rodriguez and Hadad

recount mean-spirited comments hurled at them: Hadad was told

she was wasting her talent by pursing her style of performance which

wasn't theatre at all, and Rodriguez was told she had no right to be

onstage because she was too ugly.)

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

12 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

At El habito, the audience of lefties, gays, lesbians, and intellectuals can always expect to find new political satires and other kinds

of outrageous performances by Jesusa Rodriguez and Liliana Felipe.

Irreverent and audacious, Jesusa and Liliana incorporate current

news and scandals into their brilliant skitsSalinas de Gortari,

Ernesto Zedillo and other

Mexican presidents make their

appearance, as do Bill Clinton,

Monica Lewinsky, Hitler, Sor

Juana Ines de la Cruz, Jesus

Christ, and the singer Madonna,

to mention just a few of the hundreds of famous personages to

take shape on their stage. Sometimes, the "real" politicians

themselves come to the cabaret

to see what's being said about

them. El habito also offers a full

schedule of guest appearances by

famous performers, and music

Jesusa Rodriguez and Liliana

and performance workshops for

Felipe in El cielo de abajo

a wide audience. El Teatro de la

Capilla usually features full-length plays.

El teatro de la mascara has also founded its own space in which

to workassuring the women access to a performance space and

the development of their own audience. Nonetheless, the group

undergoes constant transformation as members come and go in their

efforts to earn a living.

But even artists who don't control their own physical space have

found ways of controlling their interventions. Astrid Hadad, who

always performs with Los tarzanes (the Tarzans, her largely female

band), has worked hard to develop her own circuit of festivals and

national and international performance opportunities. Denise

Stoklos, a solo performer who writes and directs her own productions, has done likewise, managing herself and publishing her own

books. Sabina Berman, a self-employed playwright, has created a

space for herself within the Mexican theatre establishment. Having

won recognition as one of the foremost Mexican dramatists, she now

enjoys a visibility and status both nationally and internationally, and

serves as a member of the board of the writer's union, SOGEM.

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION 13

Diana Raznovich, as a dramatist

and cartoonist, works mostly by

herself in Buenos Aires, though

she too serves on the board of

Argentina's writer's union

Argentores. Griselda Gambaro

has gained major recognition

and is consistently produced in

Argentina's most prestigious

theatres. But for all her success,

she has until recently been the

sole woman to be included in

any project. Hers is usually the

only female name in Latin

American theatre festivals and

anthologies. It's been hard and

Griselda Gambaro's

it's been lonely, she admits with

Antigona Furiosa

her usual love of understatement.

While their artistic goals, media, and strategies varyone thing

remains constant: these women unsettle. Through their use of

humor, irony, parody, citationality, inversions and diversions, their

art complicates and upsets all the dogmas and convictions that dominant audiences hold near and dear. This is the art of the "outside."

These artists, holy terrors, take on the sacred cows. They fight for

the freedom to act up, act out, and call the shots. Denise Stoklos

rails openly against those whom she feels participate in the continuing travesty of Brazilian politics. Sometimes with humor, sometimes with raw indignation, she makes sure she

gets her views across. In

500 years: A Fax from

Denise Stoklos to Columbus, she explores the

role of the artist, the

intellectual, the theatre,

and the audience in the

tragic history of her

. , , .

..

.

,

country. "Read it," she

Denise Stoklos mCasa rails against the

,. ..,

,, ' .,

s ys

travesty of Brazilian politics

* :

" * *" m 'Je

7

books. Later, once the

14 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

audience fully comprehends the magnitude of her critique, she has

the house lights turned up: "The doors of the theatre are open for

those who want to abandon this ship in flames" (Stoklos 1992,

author's translation). Diana Raznovich uses the "minor" mode

the cartoonas well as her "frivolous" theatre to call attention to

the acts of everyday violence that women endure through socialization. Women are not allowed to laugh, to giggle or snigger, to

chuckle or cackle, to grin or guffaw. Women's right to pleasure is no

laughing matter, according to those who would advocate the position that "women should not laugh, it threatens the world with total

moral decomposition" (Manifesto 2000 of Feminine Humor). Women

should stifle their laughter, swallow it, block it, turn it into a cry, a

perpetual and dismal "ay ay ay." Jesusa Rodriguez and Liliana Felipe

likewise turn their formidable talents to making fun of repressive

social systems and the audience's complicity with them. And after

a night of political satire, non-stop directas e indirectas, they remind

their audience: "Seremos cabronas, pero somos las patronas." This

is their space, their art,

their turn, and they

have no intention of

giving it up.

The artists, though

committed to the disruption of oppressive

norms, share no ideological or political posi-

(Jesusa

Rodriguez,

T-ix? ir\>

_.

_

. ,, .

_ .

Diana Raznovichs\nner Gardens

Liliana relrpe, Diana

Raznovich), while others (like Denise Stoklos) might say they are

fighting all pervasive forms of oppression. Sabina Berman, while

working in and forming part of Mexico's male-controlled theatre

establishment, has forcefully introduced issues of gender and sexuality. She openly writes about lesbianism in a country where the

topic remains taboo. Moreover, she takes on the politicians directly.

Her play, Krisis, boldly reveals the true story of ex-President Salinas

de Gotari, who as a child murdered his nanny during a game. Her

critique is no less powerful for coming from the "inside." Other

artists see the answer to their marginalization in "collective" work

associated with 1960s socialist collectivessuch as El teatro de la

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION 15

mascara. For others, like Stoklos,

solo performance allows them to

carry on the politics of the one.

Even so, "solo" doesn't mean

"alone." Stoklos, for example, is

always in conversation, artistically

and ideologically, with others who

have fought for freedom. Her last

words to the late Brazilian singer

Elis Regina, in her one-woman

homage by that name, maps out the

trajectory of solidarityStoklos

quotes Regina who in turn sings

one of Mercedes Sosa's most

famous lines, "Yo tengo tantos hermanos que no los puedo contar...."

Teatro La Mascara in their

(I have so many brothers/sisters

that I can't count them all). Astrid 1995 production A Flor de Piel

Hadad, even though accompanied by her musicians, is very much a

"solo" actcombining her songs (well-known boleros, rancheras,

tnariachi pieces, and other Mexican and Latin American forms) with

performances that call attention to the way these popular forms

encapsulate and transmit violent cultural fantasies. She, like many

of these artists, takes on the Catholic Church, the State and its

authorities; the reigning norms of taste and value; and any and all

certainties pertaining to appropriate gender and sexual roles.

These artiststhough courageous and transgressive in a number

of unexpected waysnonetheless belong to a tradition of outspoken women performers and artists. Their performances (as suggested above) pay tribute to, and often "cite," the paths of trailblazers in various arts in the 20 t n century throughout Latin

America: Mercedes Sosa, Elis Regina, La Lupe, Chabuca Granda,

Frida Kahlo, Lucha Reyes, Chavela Vargas, Rosario Castellanos and

Alfonsina Storni, to name a few.3 These earlier artists had already

challenged the limits and restrictions imposed on them by the racist,

misogynist, and homophobic world in which they worked. Singers

like the puertoriquena La Lupe had defiantly answered her male,

homophobic critics in her songs: "According to your point of view/

I am the bad one," while Chavela Vargas was notorious in Mexico

for picking up female admirers in the clubs and singing her love

songs exclusively to women. Chabuca Granda, from Peru, has re-

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

16 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

worked the famous song "Adelita" to question the quietism of contemporary women: "iDonde estas, Adelita? ^Donde estas, guerrillera?" (Where are you, Adelita? Where have you gone, woman

warrior?).

In addition to citing some of the great women performers of the

mid 20 century, these recent performers also draw liberally from

popular theatre styles of the late 19 and early 20" 1 century known

as teatro frivolo or frivolous theatre. These traditions have served

not only the "frivolous" artistssuch as Diana Raznovich, Astrid

Hadad, and Jesusa Rodriguezbut the more "serious" ones as well.

Sabina Berman's plays, for example, look like traditional Western

theatre. But a study of the content and tone of her work reveals nontraditional treatment of a broad spectrum of "universal" and

Mexican themes. In some of her plays we find elements of street

theatre, indigenous theatre based on oral tradition, and soap-opera

melodrama, an important part of Mexico's cultural production and

consumption and, these artists and many others laughingly admit,

a part of Mexico's national character as well.

Teatro frivolo is important to our study not only because of its

popularity among the women studied here but because of the resurgence of interest in its forms on the part of new generations of practitioners. Artists then and now, liberated from state-controlled

spaces and academic rules of production, take advantage of the

various forms and styles of teatro frivolo such as cabaret, sketchs,

teatro de revista (revue), teatro de carpa (itinerant theatre, literally,

under a tent), and street theatre. According to Pablo Duefias and

Jesus Escalante, the term teatro de revista referred to the genre whose

particular characteristic consisted of bringing to the stage a series

of satirical dramatizations, about one hour in duration, based on real

events, actual or past (12). The tone was generally comical and the

form parodiccharacteristics of other popular genres circulating

at the time such as the Spanish zarzuela and sainete, although with

specific variations, particularly in the content of the plot. Revista

incorporated music and dance scenes. Like the zarzuela (consisting

of one to four acts) and sainete (usually one act), revista served as

portraits of customs, fashions, and traditions. Sketchs (so called

because of the outline-form the open-ended scripts took) and carpa

(theatre staged under tents that traveled throughout the Mexican

Republic, along the lines of its distant cousin the circo criollo in

Argentina) are characterized by the open participation of the spectator as an integral part of the show. Similar to revista, the parody,

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION 11

satire, and humor of the sketchs and carpa provided ample opportunity for artists and citizens to express themselves and their criticism

of all aspects of lifepolitical, economic, social, and cultural.

In this way, from the 1880s until the 1930s, people from all over

Latin America, from all social classes of the growing urban population and the provinces, mingled and participated in the ritual of

some local version oiteatrofrivolo. Writers drew their material from

daily events in the cities and throughout the provinces. Theatre and

song transmitted news and information, voiced sociopolitical criticism, and created a sense of nationhood, of national identity. Realistic and symbolic charactersincluding the street vagrant, the revolutionary, fancy cowboys, the innocent virgin, the prostitute, the

rancher, students, dancing skeletons, politicians, the cabaret diva,

and the drunkwere constructed through iconic gestures and

spoken through popular language characterized by the use ofalbures

and lunfardo, plays on words and puns with double meanings, often

with sexual connotations. Highlighted are the rich oral traditions of

popular classes imbued with an agile sense of humor and the use of

language that produces some of the most fascinating linguistic play

in the Spanish language (which also makes the translation of some

of this work difficult). This oral tradition also surfaces in the lyrics

of songs (boleros, corridas ranchera, tango, musica romdntica) which

are found at the center of popular culture, an integral part of

popular theatre.

Thus, all of these elements converged and helped crystallize the

images that audiences of these teatros had of themselves as a people.

Benedict Anderson's concept of "imagined community" works well

to describe the processes through which a geographically dispersed

and largely illiterate, heterogeneous population begins to conceive

of itself as a communitybut here it was predominantly through

performed, rather than print, culture. The representation of the elements and characters of the daily life of common people or pueblo

(the "popular" nature of the revista and these other theatrical

genres) acts as a catalyst to the emergence of the concept of local,

and even national, identities. This occurs in spite of the disdain of

the producers of elite forms, prominent men often caricatured and

criticized on revista's stages, who resignify the term "popular" to

correspond to an idea of masses, of the plebe, as vulgar.

The critics seemed to have little effect on the popularity, across

social and economic classes, of revista, carpa, and cabaret. The tight

relationship between these styles of theatre and the collective imag-

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

18 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

inary, between the producers of theatre, the public, and the

product/production, created truly "public" spaces which developed

in individuals a sense of belonging and of empowerment as they saw

themselves and their cosmovision represented on stage. Unlike classic

theatre, which comprises the largest part of most histories of theatre,

these popular forms were generated by the need for representation

and expression of the population whose tastes and realities they

reflected. Nonetheless, teatro frivolo began to fade into the background in the late 1920s and earlyl930s due to cultural trends

gaining currency in the various countries: the rise of the cinema

perhaps most particularly.

This teatro frivolo never disappeared of course. Even when the

shows themselves seemed to lose popularity, the style and humor

and intent, as well as some of the routines, lived on in other forms

and in other places. Cantinflas, Mexico's brilliant humorist and the

people's philosopher, moved from carpas to film. And the carpa tradition, which migrated north to the U.S. as part of Mexican-American popular culture, went on to inspire other kinds of popular theatresmost notably teatro Campesino in the 1960s.

For many of the women artists represented here, teatro frivolo

(and its many variations) served as a marvellous vehicleshort, critical, funny, flexiblefor achieving their own goals. Griselda

Gambaro, for example, picks up the "teatro grotesco " (a mordant and

incisive genre related to the short teatro frivolo) to convey the

grotesque character of the "Dirty War." Stripped, the one-act play

offered here, is an example of the adaptability of this genreas

capable of entertaining and playing with its audience as of critiquing

its "frivolity." This short piece brutally depicts the escalation of violence during a period of political crisis, and the inanity, even "frivolity" of the public's response. In fact, the short grotesco genre here

serves both to index and critique certain aspects of teatro frivolo

itself. For Jesusa Rodriguez, the teatro frivolo model provides a basic

and flexible framework for much of her cabaret-type performance.

In a 1999 piece, Palenque politico, Jesusa and Liliana stage a political horse race, with the candidates for Mexico's presidential election vying for the lead. In the midst of this, Chona Schopenhauer

(Jesusa) comes on in a red sequin skirt, a "folkloric" white blouse,

her hair in a ponytail and ribbons, riding a wooden horse which she

wears as a skirt held up with straps. Her philosophical reflections,

very much in the tradition of carpas and Cantinflas, elevate uncertainty to an existential condition: "We never know what's going to

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION 19

happen tomorrow," she reminds us. Life in Mexico is a crap shoot,

as fickle and as arbitrary as "la loteria nacional"a national game

along the lines of "Bingo." The audience plays and the objective lies

in being the first to fill one's board. The boards and the cards

which usually reflect traditional images such as the heart, the cactus,

the drunk, Death, the moon, the mermaid, and so forth, have been

updated to reflect Mexico's current national figuresthe wetback,

the coyote, marijuana, the ATM machine, and the cellular phone.

At the end of the game, things end the way they always do in

Mexico, with raucous accusations by actors and audience alike of

corruption and fraud.

Within the formulaic, "frivolous," and flexible framework of this

short art form, then, artists have found a broad range of possibilitiesfrom the merciless critique by Gambaro to the more playful,

yet equally trenchant attack by Jesusa Rodriguez. Astrid Hadad has

taken up a variation of this form by staging her forceful political

intervention within the traditional genre of a cabaret performance.

She sings some of Mexico's most beloved songs, only to make

explicit the violence embedded in the popular imaginary. "Me

pegasta tanto anoche" (You beat me so much last night), she sings,

holding herself up on crutches, her arm in a sling, her head bandaged. Between the songs, she carries on her political analysis: How

is Coatlicue, the Aztec mother of the gods, the same as and different from the Virgin Mary? Both got pregnant by some mysterious

immaculate conceptionCoatlicue swallowed a feather as she

swept, while the Virgin Mary was filled by the Holy Spirit. The difference? Well, Coatlicue, like all "Third World" women, was

working like a beast of burden, while her "First World" counterpart

could dedicate herself to prayer.

Astrid Hadad (like Jesusa Rodriguez, Diana Raznovich, and

Sabina Berman) also focuses on the politics of representation itself.

In her performances, she takes on some of the most "Latin American" of icons. Her costumes, elaborate constructions representing

Coatlicue, or a Diego Rivera painting, or some other famous figure,

make literal a highly coded system of stereotypical images. The set

design for her piece Heavy Nopal, for example, includes a huge

cactus, a large stuffed heart, and many of the other images people

associate with Mexico. She aims to subvert the images that have regulated the formulation of gender identity for Mexican women (from

sainted motherthe Virgin of Guadalupe or Coatilcue, the Mexicana "mother" of all Mexicansto the macho woman with high

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

20 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

heels and spurs. Hadad's Heavy Nopal suggests that the narrow grid

provided by the stereotype which reduces and fixes a one-dimensional image serves only as a critique for those who are able to see

the violence of the framing. Hadad repeatedly poses with her face

in a frame as a reminder that representational practices have long

shaped what can and cannot be seen. In a "tableaux vivant" of a

Diego Rivera painting, she humorously bears the weight of stereotypical accumulation and "anxious" repetition. She is all-in-one:

the Diego Rivera girl holding calla lilies, the soldadera (revolutionary fighter), the bejeweled Latina, loaded

down

with

rings,

bracelets and dangling

earrings, the India with

the hand-embroidered

shirt, long black braids

and a bewildered look

about her. The overmarked

image

of

telegenic

ethnicity

signals the rigid structuring of cultural visibility. The parodic selfmarking reads as one

more repetition of the

fact, one more proof of

its fixity. Latin America

is only visible through

cliche, she suggests,

known solely "in transAstrid Hadad's Heavy Nopal

lation." Hadad plays

with the anxiety behind these images of excess, pushing the most

hegemonic of spectators to reconsider how these stereotypes of cultural/racial/ethnic difference are produced, reiterated, and consumed.

In their various ways, these women have made important progress

in opening a greater discursive and representational space not only

for the issues they espouse, but also for their right to command

public attention. The reasons that women born in the 1950s and

1960s have entered previously restricted public spheres are numerous. In the Southern cone, the long periods of military dictatorship

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

INTRODUCTION 21

strengthened the resolve and even militancy of many women who

could not accept the inhuman restrictions imposed on them and

their families. Even women, like the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo,

who had never thought of themselves as "political" took to the

streets. This period saw the rise of women's political mobilization

in numerous ways: grassroots organizations, feminist groups, militancy. Another reason for the increased visibility of women throughout Latin America is economic crisis and the migrations of male

workers: more women have been forced to work outside the home

even though social mores continue to stress that a "woman's place

is in the home." Concomitantly with new market demands, women

have increased access to education and, thus, the professions.

Foreign influences, omnipresent in mass media and technology, have

also changed "local" perceptions and expectations. NAFTA, MERCOSUR and other "global" market initiatives facilitate access to

consumer goods and ideas. And, of course, people travel more than

ever, whether as tourists or as immigrants, destabilizing rigid

borders and stable identity markers. All these factors contribute to

the enhanced visibility and activity of womenalbeit slowly

throughout Latin America.

In the last decades of the 20th century, then, we witness an emergence of styles that draw directly on various popular forms and

emphasize the relation between performance and the visual arts.

The simultaneously intimate and public nature of these performance

styles contributes to attempts to interrupt social and aesthetic

systems, and to motivate and rehearse civic participation with the

spectators. The artists also put into visible circulation the traditions

that characterize Latin American cultures, so imbued with global

influences deriving from complicated histories and social circumstancesin Nestor Garcia Canclini's words, its "multitemporal heterogeneity" (3). They remind us that the much-glorified "Indigenous Past" elides the very present predicament of impoverished

native communities relegated both to the "past" and to the economic

margins. The colonial legacy of Hispanic and Roman Catholic institutions continues to exude its power, and specters of inquisitorial

scrutinizing and prohibitions continue to haunt the present. Patriarchy permeates and structures all social formations at the macroand micro-level. Meanwhile, the cultural imperialism of the U.S.

threatens to relegate performance interventions into the off off off

shadowlands of neo-colonialismpoor Latin America, so far from

God, so close to the United States, as the joke goes. Rather than

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

22 WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

accept that the "real" action is taking place somewhere else, these

performers rail back. At a performance of Heavy Nopal in Miami,

Astrid Hadad sweetly asked her audience in broken English: "Do

you understand Spanish?" When most of the audience shouted back

"NO!"

she said, "Well, learn it!" and went on with her show in

Spanish. Who's marginal now? While claims to access are constantly

being denied to minoritarian populations, this too can change. These

women assume the task of dismantling codes of signification that

bestow meaning and inscribe themselves upon the individual and

collective body. Each excavates "universal" and local sources to

uncover and expose the structures of power at the base of their

society. They recuperate and recirculate the visual, linguistic, symbolic, and, more recently, technological codes that circumscribe

identities and modalities of seeing, representing, and knowing. In

different ways, their performative styles simultaneously interrogate

the politics of representation and the strategies of power written

across the female body, which serves as both the message and the

vehicle. They expose the social theatrics that circulate Woman and

women as commodities in a landscape upon which capitalism, even

more charged in the age of neo-liberal economic treaties, so intrinsically depends. The normative habit of fixing the gaze upon the

human body is challenged through a variety of strategies, for

instance by juxtaposing light and sound, contrasting visual and tonal

elements, exposing the disembodied nature of the discourses of

power, and capturing or framing the spectator within the gaze of the

performer. The performances, in their own ways, disassemble the

sacred national and religious iconography in which Woman has been

traditionally portrayed as either saint or sinner, virgin/mother or

whore, but always passive and dangerous, in order to make explicit

its constructed, not "natural," nature. These artists create an artistic language through which ruptures and gaps produced by such

representations generate spaces of critical potential. They experiment with re-writing the scripted roles for women configured by

masculine systems at different historical moments, systems whose

authority and endurance are based on sacred textswritten, verbal,

and visualand other strategic modes of self-authorized control of

the Other.

Cultural revolutionaries and holy terrors, these performers are

every macho's nightmare, every politician's headache, every clergyman's despair. But in this particular case it might be fair to rejoice

that "from the terror of the many, comes the delight of the few."

INTRODUCTION 23

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

Notes

1. The selection of the people included here is limited, unfortunately, due to several circumstances. The good news is that there are

far too many women artists, if we include singers, performers, playwrights and directors, to include in a single volume. The bad news

is that some of the essays on artists that we very much wanted to

includeRosa Luisa Marquez, Petrona de la Cruz Cruz, Isabel

Juarez Espinosa, Teresa Rallicould not be included in this volume.

The editors see their work in this field, as well as the field itself, as

very much in progress.

2. Puerto Ricans, although they hold U.S. citizenship and passports, are not allowed to vote in U.S. presidential elections.

3. This list is in no way exhaustive. As scholars and practitioners

uncover and take a closer look at archives and cultural artifacts, and

as we rewrite theory to displace the systems of valorization that have

marginalized or ignored much artistic production, the number of

women shown to have significantly impacted the Latin American

social and cultural landscapes grows.

Works Cited

Costantino, Roselyn. 2000. "Performance in Mexico: Jesusa

Rodriguez's Body in Play." In Corpus Delecti. Performance in

Latin America, ed. Coco Fusco, 63-77. London, NY: Routledge.

. 2000. "And She Wears it Well: Feminist and Cultural

Debates in the Work of Astrid Hadad." In Latinas on Stage,

eds. Alicia Arrizn and Lillian Manzor, 398-421. Berkeley:

Third Woman Press.

Dueas, Pablo and Jess Escalante Flores, editors. 1994. Teatro mexicano. Historia y dramaturgia. XX Teatro de revista (18941936). Mxico, D.F.: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las

Artes.

Garca Canclini, Nstor. 1992. "Cultural Reconversion." Trans.

Holly Staver. In On Edge. The Crisis of Contemporary Latin

American Culture, eds. George Ydice, Jean Franco, and Juan

Flores. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hutcheon, Linda. 1989. The Politics of Postmodernism. New York:

Routledge.

U WOMEN & PERFORMANCE

Downloaded by [190.189.217.131] at 09:29 29 April 2014

Stoklos, Denise. 1992. 500 AnosUn Fax de Denise Stoklos para

Cristvo Colombo. So Paulo: Denise Stoklos Produes

Artsticas Ltda.

Taylor, Diana & Juan Villegas. 1994. Negotiating Performance.

Durham: Duke University Press.

. 1997. Disappearing Acts. Durham: Duke University Press.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Protocolo Ingles PDFDocument180 pagesProtocolo Ingles PDFsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- American Bar Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To American Bar Association JournalDocument7 pagesAmerican Bar Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To American Bar Association JournalsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Queer Latinidad-Juana María RodríguezDocument240 pagesQueer Latinidad-Juana María Rodríguezmar cendón100% (4)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 2º A 4º Prof. Musica - Teóricas y Grupales Dig 2015Document4 pages2º A 4º Prof. Musica - Teóricas y Grupales Dig 2015salomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 2º A 4º Prof. Musica - Teóricas y Grupales Dig 2015Document4 pages2º A 4º Prof. Musica - Teóricas y Grupales Dig 2015salomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Vantage Consulting CVDocument13 pagesVantage Consulting CVsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Star BurnDocument104 pagesStar BurnsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Passport To The World: EnglishDocument1 pagePassport To The World: EnglishsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 1re WTG WR 1201Document1 page1re WTG WR 1201salomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Pink Bow Tie - Supplementary PDFDocument20 pagesPink Bow Tie - Supplementary PDFsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Pink Bow Tie - SupplementaryDocument19 pagesPink Bow Tie - SupplementarysalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Pink Bow Tie - Pre-ReadingDocument2 pagesPink Bow Tie - Pre-ReadingMaria Da Guia Fonseca33% (3)

- Add Details: Drafting Ii: Completing The DraftDocument1 pageAdd Details: Drafting Ii: Completing The DraftsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Psychology: English ForDocument129 pagesPsychology: English Forsalomonmarina100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Rhetorical Functions: 7.1. Thematic StructureDocument4 pagesRhetorical Functions: 7.1. Thematic StructuresalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Translator As Rapporteur: A Concept For Training and Self-ImprovementDocument36 pagesThe Translator As Rapporteur: A Concept For Training and Self-ImprovementsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Transitivity in The YellowDocument10 pagesTransitivity in The YellowsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Rotary Peace Centers: Master's Degree Fellowship GuideDocument20 pagesRotary Peace Centers: Master's Degree Fellowship GuidesalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Terms For Literary StylisticsDocument5 pagesTerms For Literary StylisticssalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Transitivity Choices in Five Appellate Decisions in Rape CasesDocument17 pagesAn Analysis of Transitivity Choices in Five Appellate Decisions in Rape CasessalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- CliDocument28 pagesClisalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ive Got Rings On My FingersDocument6 pagesIve Got Rings On My FingerssalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Proud Mary Ike Tina Turner Man in The Mirror Sweet Dreams Karma Kamaleon ToxicDocument1 pageProud Mary Ike Tina Turner Man in The Mirror Sweet Dreams Karma Kamaleon ToxicsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Beowulf: Study GuideDocument37 pagesBeowulf: Study Guidesalomonmarina100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Linguistics and Sociolinguistics: Department of European, American and Intercultural Studies A.A. 2017-2018Document59 pagesLinguistics and Sociolinguistics: Department of European, American and Intercultural Studies A.A. 2017-2018salomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Proud Mary Ike Tina Turner Man in The Mirror Sweet Dreams Karma Kamaleon ToxicDocument1 pageProud Mary Ike Tina Turner Man in The Mirror Sweet Dreams Karma Kamaleon ToxicsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Pink Bow Tie - Supplementary PDFDocument20 pagesPink Bow Tie - Supplementary PDFsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Este Tiempo Fue Suficiente o Esta Vez Fue Suficiente?Document1 pageEste Tiempo Fue Suficiente o Esta Vez Fue Suficiente?salomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- YoungDocument1 pageYoungsalomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Este Tiempo Fue Suficiente o Esta Vez Fue Suficiente?Document1 pageEste Tiempo Fue Suficiente o Esta Vez Fue Suficiente?salomonmarinaNo ratings yet

- Today's Fallen Heroes Thursday 20 September 1917 (4648)Document94 pagesToday's Fallen Heroes Thursday 20 September 1917 (4648)MickTierneyNo ratings yet

- Alvar Aalto A Life's WorkDocument10 pagesAlvar Aalto A Life's WorkSanyung LeeNo ratings yet

- Walter Smith III TransctiptionsDocument18 pagesWalter Smith III TransctiptionsLastWinterSnow67% (3)

- Complete Catalogue of Works 2014 (More Than 800)Document124 pagesComplete Catalogue of Works 2014 (More Than 800)maribelNo ratings yet

- Alan Ayckbourn Plays 5 (Alan Ayckbourn)Document435 pagesAlan Ayckbourn Plays 5 (Alan Ayckbourn)Javier Montero100% (2)

- Beauty WithinDocument5 pagesBeauty Withinapi-385681102No ratings yet

- 666 2441 1 PB PDFDocument15 pages666 2441 1 PB PDFiramNo ratings yet

- Rachmaninoff - Concierto 3 (Versiones)Document5 pagesRachmaninoff - Concierto 3 (Versiones)gatochaletNo ratings yet

- 7 Minnesota&Civil WarDocument2 pages7 Minnesota&Civil Warjohns032No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Romeo and Juliet Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesRomeo and Juliet Research Paper Topicspnquihcnd100% (1)

- Healesville Map v9Document1 pageHealesville Map v9arddra92No ratings yet

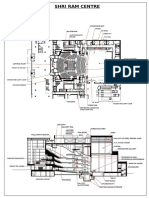

- Shri Ram Center AudiDocument21 pagesShri Ram Center Audiparitosh100% (1)

- Name: Novra Yunanda NPM: 1118101033 Class: ADocument2 pagesName: Novra Yunanda NPM: 1118101033 Class: ANovra YunandaNo ratings yet

- Tanghalang Pilipino Foundation, IncDocument4 pagesTanghalang Pilipino Foundation, Incpaulo empenioNo ratings yet

- Bien Doi Cau Cuc Kho Co Dap AnDocument14 pagesBien Doi Cau Cuc Kho Co Dap AnHồ Viết TiênNo ratings yet

- Oostburg High School Vocal Jazz and Pop HandbookDocument3 pagesOostburg High School Vocal Jazz and Pop Handbookapi-280684843No ratings yet

- Ma Shwe OoDocument2 pagesMa Shwe OoNyanWahNo ratings yet

- Final Exam EssayDocument1 pageFinal Exam EssayLovely LachelleNo ratings yet

- María Delgado, Blood Wedding (1932)Document16 pagesMaría Delgado, Blood Wedding (1932)Giovanny SalasNo ratings yet

- ELEX Vestibulum 2014 HR Sime DemoDocument8 pagesELEX Vestibulum 2014 HR Sime DemoMladen BosnjakNo ratings yet

- Yahaira Hernandez ResumeDocument1 pageYahaira Hernandez Resumeapi-403699858No ratings yet

- Comedy Definition of Comedy: Example #1: A Midsummer Night's Dream (By William Shakespeare)Document5 pagesComedy Definition of Comedy: Example #1: A Midsummer Night's Dream (By William Shakespeare)Lovely Mae ReyesNo ratings yet

- (Clarinet Institute) Mendelssohn Wedding March Alto Sax PDFDocument4 pages(Clarinet Institute) Mendelssohn Wedding March Alto Sax PDFSale SaxNo ratings yet

- Errata Storm Above The Reich Aug 11 2021Document1 pageErrata Storm Above The Reich Aug 11 2021David MuñozNo ratings yet

- Modern Drama QsDocument9 pagesModern Drama QsHanonNo ratings yet

- UW Cinematheque Spring 2014 Screening CalendarDocument22 pagesUW Cinematheque Spring 2014 Screening CalendarIsthmus Publishing CompanyNo ratings yet

- History of AcousticsDocument21 pagesHistory of Acousticssalma mirNo ratings yet

- Resume - William DwyerDocument1 pageResume - William Dwyerapi-240119562No ratings yet

- (Macmillan Modern Dramatists) Ronald Speirs (Auth.) - Bertolt Brecht-Macmillan Education UK (1987) PDFDocument212 pages(Macmillan Modern Dramatists) Ronald Speirs (Auth.) - Bertolt Brecht-Macmillan Education UK (1987) PDFglorisa100% (1)

- Icse 2024 Specimen 951 DmaDocument9 pagesIcse 2024 Specimen 951 Dma02. ABDUL REHMANNo ratings yet