Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Caribbean Studies Book Review

Uploaded by

h6329lopezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Caribbean Studies Book Review

Uploaded by

h6329lopezCopyright:

Available Formats

Caribbean Studies

ISSN: 0008-6533

iec.ics@upr.edu

Instituto de Estudios del Caribe

Puerto Rico

Lpez-Sierra, Hctor E.

Mercedes Cros Sandoval. 2006. Worldview, the Orichas, and Santera: Africa to Cuba and Beyond.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida. 417 pp. Cloth: ISBN 13: 978-0-8130-3020-3.

Caribbean Studies, vol. 40, nm. 1, enero-junio, 2012, pp. 211-216

Instituto de Estudios del Caribe

San Juan, Puerto Rico

Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39225841017

How to cite

Complete issue

More information about this article

Journal's homepage in redalyc.org

Scientific Information System

Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal

Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative

Reseas de libros Books Reviews Comptes Rendus

211

Jankees essay concludes the volume by looking at the role of the internet

in constructing the Jamaican identity.

While the collection succeeds in offering the reader a peek into the

scope of Brathwaites work and legacy, it suffers from a few weak points.

First, many articles had little engagement with Brathwaite. For instance

Devonishs essay in part one offers a compelling analysis of calypso as a

performance speech act, but without situating Brathwaite in the research.

The inclusion of this essay is further questioned by Edwardss inability

to elucidate the connection in his introduction. Other essays, such as

Jankees, that do reference Brathwaite, do so in an abbreviated manner

which suggests the relationship is tenuous at best. This failing could have

been avoided if each section began with an introduction. Edwards does

an amazing job linking the essays in his introduction, but considering the

length of this volume, their inclusion at the start of each section might

have been more helpful. Finally, the collection could have benefited from

a concluding essay about the possible future contributions of Brathwaite.

While Jankees essay explores the possibilities of Brathwaite in cyberspace, this future was limited to the spread of nation language. What

about the future impact of creolization? How can Brathwaite guide our

understanding of the transnational Caribbean? Despite this feeling of

incompletion, which is probably a conscious aim of the editor, Caribbean

Culture is still a satisfying tribute to Kamau Brathwaite that will inspire

most readers to seek out and engage his work more.

Mercedes Cros Sandoval. 2006. Worldview, the Orichas, and

Santera: Africa to Cuba and Beyond. Gainesville: University

Press of Florida. 417 pp. Cloth: ISBN 13: 978-0-8130-3020-3.

Hctor E. Lpez-Sierra

Inter American University of Puerto Rico

Metropolitan Campus

hlopez@intermetro.edu

ercedes Cros Sandoval is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Social Sciences at Miami Dade College and former

adjunct professor of anthropology, Department of Psychiatry, at the

School of Medicine of the University of Miami. Her book, Worldview,

the Orichas, and Santera: Africa to Cuba and Beyond, is organized in

Vol. 40, No. 1 (January - June 2012)

Caribbean Studies

212

Hctor E. Lpez-Sierra

twenty-four chapters with their respective conclusions, and divided in

three parts. It also includes seven appendixes (pp. 359-371). In terms of

the methodology utilized to collect religious systems data, Cros Sandoval

uses the following techniques: historical data analysis, formal interviews,

participant observation, intimate personal conversations, recorded

oral histories and musical reminiscences, as well as content analysis of

Santeras priests and priestesses notebooks (pp. xxx-xxxii).

Part 1 of this work addresses the origins of Santera (pp. 1-160). It

describes aspects of the worldview of the Yoruba religion and characteristics of the worldview of a large portion of the Cuban population that

were shared with the author through interviews. It also describes the

establishment and development of this religion in Cuba; its structure,

religious paraphernalia, and practices. Included in this section is a biographical account that sheds light and provides information on Santeras

functions and accommodations within a rural setting. In this section, the

author discusses the loss of some of the Yoruba beliefs about reincarnation and the consequences of this loss for the religion. An additional

discussion in this section is the significant value that Santeras function

as a health and wellbeingtherapeuticdelivery system has had in

attracting new adherents, especially Cuban non-blacks and people of

non-Cuban extraction.

Part 2 provides a comparison of the Orichas in Africa and their

corresponding deities in Cuban Santera (pp. 161-306). This section

is an English version, revised and expanded, of Cros Sandovals book

La religin afrocubana (1975). It includes an extensive description of

Nigerian and Afro-Cuban religious mythology. This segment is an effort

to engage the reader in both the humane, and the extraordinary and

supernatural elements and environment of Santera. The purpose is to

provide a substantial basis for interpreting types and degrees of change

in Santera.

In part 3 (pp. 307-358) the author focuses on the changes that have

occurred to Santera in the island and in exile since the Cuban Revolution. It concludes with New Ways and Current Trends in Santera

practice and suggests that worldview analysis of Santera (which is based

in Michael Kearney and Florence Kluckhohns Models for Worldview Analysis (pp. xvii-xix) in new historical, socio-cultural, religious,

political, and ecological contexts will be important, almost essential, for

our understanding of cultural continuities and change in this specific

African-derived religion in the Americas in the future. Systematically

exploring every facet of Santerias worldview, Sandoval examines how

practitioners have adapted received beliefs and practices in order to

reconcile them with new environments, from plantation slavery to exile

in the United States of America.

Caribbean Studies

Vol. 40, No. 1 (January - June 2012)

Reseas de libros Books Reviews Comptes Rendus

213

In this section, Cros Sandoval also discusses the moral dimensions of

Santera, providing an outline of some of the ideals of behavior that are

inhered in this religious system. The reason for this discussion is that the

intermediary divinities (Orichas), along with all other Santerias Supreme

Being (Olodumare) creations, reflect the simultaneous characteristics

of virtuosity and malevolency, components of their essential nature. It

also elaborates upon the value and usefulness of worldview analysis as

related to the authors understanding of religious logico-structural integration. This sort of analysis and understanding contributes to a better

comprehension of continuity and change processes in Santera conceived

as a cultural and religious system (pp. 307-358). Such examination and

understanding supports her general hypothesis concerning the linkage

that relates West African Yoruba worldviews and Afro-Cuban Santera.

Ultimately, she asserts that the presence of both structural consistencies

and inconsistencies between West African and Afro-Cuban religious

traditions, reveals that the correlation which links Yoruba and La Regla

de Ocha religious practices is not fully sustainable (pp. 321-322).

At the conclusion of the book we find the appendixes (pp. 359-371),

the notes, the glossary, the references, and an Index. In the appendixes,

Cros Sandoval provides brief descriptions of the routes, or different

pathways, of the following seven Orichas: Obatal, Eleggu, Chang,

Ochn, Yemay, Babal Ay, and Ogn. By finishing the book this way,

Cros Sandoval evidences that worldview, the Orichas, and Santera are

particularly relevant resources for the gathering and analytical presentation of mythological tales interconnected to both West African Yoruba

religious practices and Afro-Cuban Santera.

The distinctive contribution of Cros Sandoval in this work is that

she comprehends the adjustment process that gave birth to Santera as a

successful attempt to find meaning associated to alien religious elements

in a way that may appeal to a diverse following. She looked at Santera

not as a singular result of cultural resistance, but as a manifestation of

the religious syncretic processes that were forging Cuban culture nurtured by what she conceives to be a spiritual and mystical point-of-view,

widespread in both Cuba and West African Yorubaland (pp. 347-354).

The author also examines the transatlantic history of how Yoruba

traditions came to Cuba and conversely flourished and adjusted to Cuban

society. She provides a comprehensive comparison of Yoruba and AfroCuban religions along with an overview of how Santera has continued

to disseminate and change in response to new contexts and adherents

with an especially illuminating perspective on Santera among Cubans

in Miami. This adaptation process was not yet a particular result of

cultural conflict and struggle, she argues, but a successful endeavor to

find meaning connected to unfamiliar religious elements in a way that

Vol. 40, No. 1 (January - June 2012)

Caribbean Studies

214

Hctor E. Lpez-Sierra

appealed to a diverse following (pp. 308-355).

From an extensive and extended research, initiated forty years ago

with her doctoral dissertation Lo Yoruba en la Santera Afrocubana (1966)

(p. xxx), Cros Sandovals worldview theoretical framework, allowed her

to deepen into the history and religious practices of Santera and its

Yoruba aspects in Afro-Cuban, Cuban American, and Caribbean manifestations (pp. xvii-xix; pp. 307-358).

The author assumes anthropologist Michael Kearneys theoretical

notion of worldview. This notion could be defined as the overall cognitive

framework of ideas and actions in society. Furthermore, the worldview of

a people is their way of looking at reality. It consists of basic assumptions

and images that provide a more or less coherent way of thinking about

the world. A worldview comprises images of Self and of all that is recognized as not-Self, plus ideas about relationships between them, among

other ideas. In that sense, Mercedes Cros Sandoval has introduced into

the research discourse on Santera the value of a worldview approach as

a means of understanding the dynamics of cultural change within a religious framework. This approach will bring fresh insights and theoretical

challenges to scholars in the field. It will also bring new conceptualizations and knowledge to readers who may not otherwise appreciate the

full significance of the comprehensive study she has undertaken.

Cros Sandoval believes that Kearneys theoretical understanding is

a sound tool for comprehending socially constructed human consciousness and the cognitive framework that supports a groups lifestyle. As

such, worldview provides a logical or cognitive matrix that may be used

as a basis for comparison when people from different cultures are placed

in situations of coexistence in spite of the manner in which such a situation comes about. Worldview analysis helps us to perceive the extent

of congruencies, or lack thereof, in the lifestyles of groups in contact.

This type analysis seeks to enrich scientific research of AfroCaribbean religions, explaining how pan-cultural features of the human

mind, interacting with their natural and social environments, inform

and constrain religious thought and action and promise to yield new

evidence regarding how the structures of the human mind informs and

constrains religious expression including ideas about gods and spirits,

the afterlife, spirit possession, prayer, ritual, religious expertise, and connections between religious thought and morality, and social behavior or

action. For the author, these theoretical assumptions offer also a means

of analysis that may help to understand cultural continuities as well as

the process of cultural borrowing, syncretism (the coming together), and

merging (transculturation)a process that gives rise to something new

but, at the same time, something that has emerged from tradition. She

applies this approach to understand Santeras dynamic processes of

Caribbean Studies

Vol. 40, No. 1 (January - June 2012)

Reseas de libros Books Reviews Comptes Rendus

215

cultural association, borrowing, and adaptation, prompted by the abrupt

contact of groups of people from different cultural traditions. In doing

this, she examines how practitioners have modified received beliefs and

practices to adapt themselves to new situations, from plantation slavery

to diaspora and exile in the Americas and the Caribbean. In summary,

her understanding is that this theoretical approach helps us comprehend

Santeras continuity and change process (pp. xvii-xix; pp. 307-358).

As a sociologist of religion, who recently finished a doctoral degree

with emphasis in learning and cognitive psychology, I find Mercedes

Cros books theoretical analysis approach to be a valuable contribution

to the newly emerging dialogue between interdisciplinary social sciences,

cognitive sciences, and neurosciences.

Given the clinical-health context of her academic and anthropological work on Yoruba and Afro-Cuban religions from a cognitive

framework of ideas and actions in society, this book appeals to fields

such as evolutionary anthropology, medical anthropology, psychological

anthropology, neuroanthropology, and the rapidly developing area of

interdisciplinary research in cognitive studies of religion; all academic

and research areas which characterize recently developments in anthropological science.

Finally, Worldview, the Orichas, and Santera: Africa to Cuba and

Beyond has a relevant limitation. Although Cros Sandovals understanding of Santera derives from a broad cultural knowledge of archaeology,

historical events, classic texts of West African art history, and cognitive

theories, unfortunately she did not perform fieldwork in West Africa.

Given that she approaches the emergence of Afro-Cuban Santera

from a worldview theory, it would be valuable to have performed ethnographic fieldwork in West Africa as a way of comparing more rigorously

the original Yorubas consciousness and cognitive framework of its

religious meaning system with that of present day Santera. The goal

for applying this method should be to understand empirically validate

the socially constructed cognitive framework which supports Santeras

dynamic processes of cultural and religious association, adaptation, and

modification in the context of received beliefs and practices in plantation

slavery economy, diaspora, and exile in the Americas and the Caribbean.

Ethnographic field study in Africa was merited in this case in order

to explain and comprehend the areas of meaning that allow people to

continue on an identifiable sociostructural path that also allows variations while preserving a fundamental meaning-system that supports cultural continuities in the face of change (transculturative processes) in

Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean Santera. It will also help explain the

loss or diminished role of some of the original African Yoruba Orichas

(divinities) in Cuba and the Caribbean (pp. 14-17 & chapter 22).

Vol. 40, No. 1 (January - June 2012)

Caribbean Studies

216

Hctor E. Lpez-Sierra

References

Cros Sandoval, Mercedes. 1975. La religin afrocubana. Preface by Lydia

Cabrera. Madrid: Playor.

Cros, Mercedes. 1966. Lo Yoruba en la Santera afrocubana. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Madrid.

Caribbean Studies

Vol. 40, No. 1 (January - June 2012)

You might also like

- Yoruba Diaspora Religions BibliographyDocument5 pagesYoruba Diaspora Religions BibliographyClaudio Daflon0% (1)

- The Study of Islam and Muslim CommunitieDocument20 pagesThe Study of Islam and Muslim CommunitieArely MedinaNo ratings yet

- African Pentecostalism and World Christianity: Essays in Honor of J. Kwabena Asamoah-GyaduFrom EverandAfrican Pentecostalism and World Christianity: Essays in Honor of J. Kwabena Asamoah-GyaduNo ratings yet

- Society, the Sacred and Scripture in Ancient Judaism: A Sociology of KnowledgeFrom EverandSociety, the Sacred and Scripture in Ancient Judaism: A Sociology of KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- Negotiating Identity: Exploring Tensions between Being Hakka and Being Christian in Northwestern TaiwanFrom EverandNegotiating Identity: Exploring Tensions between Being Hakka and Being Christian in Northwestern TaiwanNo ratings yet

- Reenchantment of The WestDocument3 pagesReenchantment of The WestEvan DeliFi100% (1)

- Test Bank For Nutrition Through The Life Cycle 7th Edition BrownDocument34 pagesTest Bank For Nutrition Through The Life Cycle 7th Edition Browncurbless.sociable7dmyeNo ratings yet

- Religions in Yorubaland: The Interaction of Pastors and Babalawos in 19th Century NigeriaDocument33 pagesReligions in Yorubaland: The Interaction of Pastors and Babalawos in 19th Century NigeriaAngel SánchezNo ratings yet

- Ridhuan Wu Issues InCross-Cultural Dakwah0001Document17 pagesRidhuan Wu Issues InCross-Cultural Dakwah0001Muallim AzNo ratings yet

- Milind Wakankar-Subalternity and Religion The Prehistory of Dalit Empowerment in South Asia (Intersections Colonial and Postcolonial Histories) - Routledge (2010)Document109 pagesMilind Wakankar-Subalternity and Religion The Prehistory of Dalit Empowerment in South Asia (Intersections Colonial and Postcolonial Histories) - Routledge (2010)Abhitha SJNo ratings yet

- Religion and FoodDocument4 pagesReligion and FoodMihail MariniucNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test Bank For Diversity Amid Globalization 7th Edition Rowntree PDF Full ChapterDocument35 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Diversity Amid Globalization 7th Edition Rowntree PDF Full Chapterreportermaterw8s84n100% (18)

- A Comparative Sociology of World Religions: Virtuosi, Priests, and Popular ReligionFrom EverandA Comparative Sociology of World Religions: Virtuosi, Priests, and Popular ReligionNo ratings yet

- Missionary Christianity and Local Religion: American Evangelicalism in North India, 1836-1870From EverandMissionary Christianity and Local Religion: American Evangelicalism in North India, 1836-1870No ratings yet

- African Religions: Exploring Origins, Traditions, and Contemporary RelevanceFrom EverandAfrican Religions: Exploring Origins, Traditions, and Contemporary RelevanceNo ratings yet

- Words and Worlds Turned Around: Indigenous Christianities in Colonial Latin AmericaFrom EverandWords and Worlds Turned Around: Indigenous Christianities in Colonial Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- STRMISKA, Michael. Modern Paganism in World Cultures - Comparative Perspectives PDFDocument393 pagesSTRMISKA, Michael. Modern Paganism in World Cultures - Comparative Perspectives PDFBruna Costenaro100% (4)

- The Church and Development in Africa, Second Edition: Aid and Development from the Perspective of Catholic Social EthicsFrom EverandThe Church and Development in Africa, Second Edition: Aid and Development from the Perspective of Catholic Social EthicsNo ratings yet

- Hindu Ritual at the Margins: Innovations, Transformations, ReconsiderationsFrom EverandHindu Ritual at the Margins: Innovations, Transformations, ReconsiderationsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Art and Architecture of The Worlds ReligionsDocument435 pagesArt and Architecture of The Worlds ReligionsAshutosh Griwan100% (10)

- Eliade, Mircea & Kitagawa, Joseph M (Eds.) - The History of Religion PDFDocument129 pagesEliade, Mircea & Kitagawa, Joseph M (Eds.) - The History of Religion PDFjalvarador1710No ratings yet

- The Post-Conciliar Church in Africa: No Turning Back the ClockFrom EverandThe Post-Conciliar Church in Africa: No Turning Back the ClockNo ratings yet

- Caribbean ReligionsDocument12 pagesCaribbean Religionsliz viloriaNo ratings yet

- Person and God in a Spanish Valley: Revised EditionFrom EverandPerson and God in a Spanish Valley: Revised EditionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- (Women and Religion in The World) Sylvia Marcos (Editor) - Women and Indigenous Religions (Women and Religion in The World) - Praeger (2010) PDFDocument267 pages(Women and Religion in The World) Sylvia Marcos (Editor) - Women and Indigenous Religions (Women and Religion in The World) - Praeger (2010) PDFAnonymous QNu8I48100% (1)

- Dr. Héctor E. López-Sierra Academic and Research ProfileDocument4 pagesDr. Héctor E. López-Sierra Academic and Research Profileh6329lopezNo ratings yet

- Yorùbá Culture: A Philosophical AccountFrom EverandYorùbá Culture: A Philosophical AccountRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Genders, Sexualities, and Spiritualities in African PentecostalismDocument426 pagesGenders, Sexualities, and Spiritualities in African PentecostalismEliyaNo ratings yet

- Holy Time and Popular Invented Rituals in Islam Structures and SymbolismDocument34 pagesHoly Time and Popular Invented Rituals in Islam Structures and SymbolismMujiburrahmanNo ratings yet

- 10.18574 Nyu 9780814728253.003.0004Document2 pages10.18574 Nyu 9780814728253.003.0004Alex100% (1)

- Yoruba Religous TraditionDocument35 pagesYoruba Religous TraditionSidney Davis100% (1)

- Convivencia Literaria en El Medievo Peninsular PDFDocument356 pagesConvivencia Literaria en El Medievo Peninsular PDFValentina Villena FloresNo ratings yet

- African Studies Review: Meanings and Expressions. Volume 3 of WorldDocument5 pagesAfrican Studies Review: Meanings and Expressions. Volume 3 of WorldMuna Chi0% (1)

- Translating Virasaivism The Early Modern Monastery PDFDocument40 pagesTranslating Virasaivism The Early Modern Monastery PDFSoftbrainNo ratings yet

- Christianity in East and Southeast AsiaDocument3 pagesChristianity in East and Southeast AsiaThi NguyenNo ratings yet

- Campany, Robert Ford-On The Very Idea of ReligionsDocument34 pagesCampany, Robert Ford-On The Very Idea of Religionsandreidirlau1No ratings yet

- Indigenous Encounters With Christian Missionaries in China and West Africa, 1800-1920Document44 pagesIndigenous Encounters With Christian Missionaries in China and West Africa, 1800-1920subscribed14No ratings yet

- AFRO-cuban Religions PDFDocument75 pagesAFRO-cuban Religions PDFYaimary Rodrguez80% (5)

- Jiabs 14-2Document155 pagesJiabs 14-2JIABSonline100% (1)

- Afro-Cuban Diasporan Religions - A Comparative Analysis of The Lit-1Document76 pagesAfro-Cuban Diasporan Religions - A Comparative Analysis of The Lit-1John Torres100% (1)

- Restoring Identities: The Contextualizing Story of Christianity in OceaniaFrom EverandRestoring Identities: The Contextualizing Story of Christianity in OceaniaUpolu Lumā VaaiNo ratings yet

- University of New MexicoDocument10 pagesUniversity of New MexicoJuan c ANo ratings yet

- Oduduwa's Chain: Locations of Culture in the Yoruba-AtlanticFrom EverandOduduwa's Chain: Locations of Culture in the Yoruba-AtlanticRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Where Men Are Wives and Mothers Rule: Santería Ritual Practices and Their Gender ImplicationsDocument199 pagesWhere Men Are Wives and Mothers Rule: Santería Ritual Practices and Their Gender ImplicationsMarinaNo ratings yet

- Religions in Early Medieval China and the Modern WestDocument34 pagesReligions in Early Medieval China and the Modern WestCalvin LinNo ratings yet

- "You Know, Abraham WM Really The First Immigrant": Religion and Trunsnutiond Mi AtionDocument27 pages"You Know, Abraham WM Really The First Immigrant": Religion and Trunsnutiond Mi AtionsilviarelferNo ratings yet

- African Traditional Religion in South AfricaDocument476 pagesAfrican Traditional Religion in South AfricajuliabikNo ratings yet

- The Two Taríacuris and the Early Colonial and Prehispanic Past of MichoacánFrom EverandThe Two Taríacuris and the Early Colonial and Prehispanic Past of MichoacánNo ratings yet

- Society For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressDocument27 pagesSociety For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressnahuelNo ratings yet

- Lamujernegrae Yemanjen Brasil CONABSTRACTDocument16 pagesLamujernegrae Yemanjen Brasil CONABSTRACTDiego PeñaNo ratings yet

- Ej 1169262Document15 pagesEj 1169262ESTHER OGODONo ratings yet

- Sylvia Marcos, Cheryl A. Kirk-Duggan, Lillian Ashcraft-Eason, Karen Jo Torjesen-Women and Indigenous Religions (Women and Religion in The World) - Praeger (2010)Document267 pagesSylvia Marcos, Cheryl A. Kirk-Duggan, Lillian Ashcraft-Eason, Karen Jo Torjesen-Women and Indigenous Religions (Women and Religion in The World) - Praeger (2010)andrada_danilescuNo ratings yet

- 684499Document3 pages684499ankitabhitale2000No ratings yet

- Role of Shamanism in Mesoamerican ArtDocument38 pagesRole of Shamanism in Mesoamerican Artsatuple66No ratings yet

- Warner, R. Stephen, Religion, Boundaries, and BridgesDocument23 pagesWarner, R. Stephen, Religion, Boundaries, and BridgesHyunwoo KooNo ratings yet

- The Supportive Roles of Religion and Spirituality.16Document9 pagesThe Supportive Roles of Religion and Spirituality.16h6329lopezNo ratings yet

- Articulo Journal Health and Human ExprienceDocument12 pagesArticulo Journal Health and Human Exprienceh6329lopezNo ratings yet

- Table 1Document4 pagesTable 1h6329lopezNo ratings yet

- PresentationDocument36 pagesPresentationh6329lopezNo ratings yet

- BHS 320 Community Building Principles and StrategiesDocument8 pagesBHS 320 Community Building Principles and Strategiesh6329lopezNo ratings yet

- Dr. Héctor E. López-Sierra Academic and Research ProfileDocument4 pagesDr. Héctor E. López-Sierra Academic and Research Profileh6329lopezNo ratings yet

- Religions and identity in Cuban societyDocument5 pagesReligions and identity in Cuban societyh6329lopezNo ratings yet

- A Review On Translation Strategies of Little Prince' by Ahmad Shamlou and Abolhasan NajafiDocument9 pagesA Review On Translation Strategies of Little Prince' by Ahmad Shamlou and Abolhasan Najafiinfo3814No ratings yet

- 2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dDocument32 pages2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dRawats002No ratings yet

- 2Document5 pages2Frances CiaNo ratings yet

- Revolutionizing Via RoboticsDocument7 pagesRevolutionizing Via RoboticsSiddhi DoshiNo ratings yet

- KT 1 Ky Nang Tong Hop 2-ThươngDocument4 pagesKT 1 Ky Nang Tong Hop 2-ThươngLệ ThứcNo ratings yet

- ModalsDocument13 pagesModalsJose CesistaNo ratings yet

- ACS Tech Manual Rev9 Vol1-TACTICS PDFDocument186 pagesACS Tech Manual Rev9 Vol1-TACTICS PDFMihaela PecaNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Conflicts and PeacekeepingDocument2 pagesEthnic Conflicts and PeacekeepingAmna KhanNo ratings yet

- Passive Voice Exercises EnglishDocument1 pagePassive Voice Exercises EnglishPaulo AbrantesNo ratings yet

- Step-By-Step Guide To Essay WritingDocument14 pagesStep-By-Step Guide To Essay WritingKelpie Alejandria De OzNo ratings yet

- R19 MPMC Lab Manual SVEC-Revanth-III-IIDocument135 pagesR19 MPMC Lab Manual SVEC-Revanth-III-IIDarshan BysaniNo ratings yet

- Food Product Development - SurveyDocument4 pagesFood Product Development - SurveyJoan Soliven33% (3)

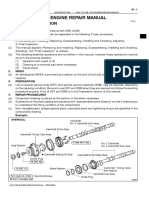

- How To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationDocument3 pagesHow To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationHenry SilvaNo ratings yet

- GDJMDocument1 pageGDJMRenato Alexander GarciaNo ratings yet

- Icici Bank FileDocument7 pagesIcici Bank Fileharman singhNo ratings yet

- Autos MalaysiaDocument45 pagesAutos MalaysiaNicholas AngNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Family Background and Academic Performance of Secondary School StudentsDocument57 pagesThe Relationship Between Family Background and Academic Performance of Secondary School StudentsMAKE MUSOLININo ratings yet

- Arpia Lovely Rose Quiz - Chapter 6 - Joint Arrangements - 2020 EditionDocument4 pagesArpia Lovely Rose Quiz - Chapter 6 - Joint Arrangements - 2020 EditionLovely ArpiaNo ratings yet

- Nazi UFOs - Another View On The MatterDocument4 pagesNazi UFOs - Another View On The Mattermoderatemammal100% (3)

- Page 17 - Word Connection, LiaisonsDocument2 pagesPage 17 - Word Connection, Liaisonsstarskyhutch0% (1)

- UG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebDocument57 pagesUG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebAnonymous 8aj9gk7GCLNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Students Pronounciation Errors Made by Ninth Grade of Junior High School 1 TengaranDocument22 pagesAn Analysis of Students Pronounciation Errors Made by Ninth Grade of Junior High School 1 TengaranOcta WibawaNo ratings yet

- MatriarchyDocument11 pagesMatriarchyKristopher Trey100% (1)

- Apple NotesDocument3 pagesApple NotesKrishna Mohan ChennareddyNo ratings yet

- Speech Writing MarkedDocument3 pagesSpeech Writing MarkedAshley KyawNo ratings yet

- 1 - Nature and Dev - Intl LawDocument20 pages1 - Nature and Dev - Intl Lawaditya singhNo ratings yet

- Maternity and Newborn MedicationsDocument38 pagesMaternity and Newborn MedicationsJaypee Fabros EdraNo ratings yet

- Bianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesDocument1 pageBianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesSyafiq IshakNo ratings yet

- Sample Letter of Intent To PurchaseDocument2 pagesSample Letter of Intent To PurchaseChairmanNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan Math 10 Module 2Document1 pageWeekly Home Learning Plan Math 10 Module 2Yhani RomeroNo ratings yet