Professional Documents

Culture Documents

De Los Santos vs. de La Cruz (Beltran & Mauna)

Uploaded by

Arvin Glen BeltranCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

De Los Santos vs. de La Cruz (Beltran & Mauna)

Uploaded by

Arvin Glen BeltranCopyright:

Available Formats

Beltran, Arvin Glen B.

Mauna, Sharima B.

TAX 2 - ACA

I. TITLE

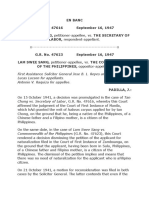

DE LOS SANTOS v DE LA CRUZ

G.R. No. L-29192

VILLAMOR; February 22, 1971

II. SUMMARY OF CASE FACTS

Pelagia de la Cruz, who died intestate on October 16, 1962, is the

owner of the land which is the subject matter of the extra-judicial partition

agreement. The defendant is the nephew of the deceased Pelagia de la Cruz.

While the plaintiff is the grandniece of the said Pelagia de la Cruz. The

mother of the plaintiff, Marciana de la Cruz, died on September 22, 1935.

Both parties admit the existence and execution of the "Extra-Judicial

Partition Agreement" dated August 24, 1963 and that the original purpose of

the Extra-Judicial Partition Agreement is to divide and distribute the land

among the heirs of Pelagia de la Cruz. The parties thereto had agreed to

adjudicate three (3) lots to the defendant, in addition to his corresponding

share, on condition that the latter would undertake the development and

subdivision of the estate, all expenses in connection therewith to be defrayed

from the proceeds of the sale of the aforementioned three (3) lots. But the

defendant refused to perform his aforesaid obligation although he had

already sold the aforesaid lots.

The plaintiff prayed the court to order the defendant to comply with

his obligation under the extrajudicial partition agreement and to pay the sum

of P1,000.00 as attorney's fees and costs.

III. SUPREME COURT DECISION

On November 3, 1966, The court ordered the defendant "to perform his

obligations to develop Lots 1, 2 and 3 of (LRC) Psd-29561 as described on

page 2 of the Extrajudicial Partition Agreement, and to pay the plaintiff the

sum of P2,000.00 as actual damages, the sum of P500.00 as attorney's fees,

and the costs. No disposition was made of defendant's counterclaim. The

defendant filed a "Motion for New Trial" but the same was denied.

The defendant appealed to higher court and the defendant-appellant is

apparently correct in his contentions. The judgment appealed from is

reversed and set aside. The defendant-appellant is absolved from any ability

to and in favor of plaintiff-appellee. On appellant's counterclaim, appellee is

hereby sentenced to restore or reconvey to him his corresponding share of

the property she has received under the extrajudicial partition hereinbefore

mentioned if the same has not already been disposed of as alleged. Costs in

both instance against plaintiff-appellee.

IV. EXPLANATION AND BASIS OF DECISION

The Plaintiff being a mere grandniece of Pelagia de la Cruz could not

inherit from the latter by right of representation. The law provides in ART.

972 that The right of representation takes place in the direct descending

line, but never in the ascending.

Much less could plaintiff-appellee inherit in her own right. The law provides

in ART. 962 that In every inheritance, the relative nearest in degree

excludes the more distant ones, saving the right of representation when it

properly takes place. ... .

In the present case, the relatives "nearest in degree" to Pelagia de la Cruz

are her nephews and nieces, one of whom is defendant-appellant.

Necessarily, plaintiff-appellee, a grandniece is excluded by law from the

inheritance.

Plaintiff-appellee not being such a heir, the partition is void with respect to

her. Article 1105 of the Civil Code provides that A partition which includes a

person believed to be a heir, but who is not, shall be void only with respect

to such person.

The extrajudicial partition agreement being void with respect to plaintiffappellee, she may not be heard to assert estoppel against defendantappellant. Estoppel cannot be predicated on a void contract (17 Am. Jur.

605), or on acts which are prohibited by law or are against public policy

(Baltazar vs. Lingayen Gulf Electric Power Co., et al., G.R. Nos. 16236-38,

June 30, 1965 [14 SCRA 5221).

The award of actual damages in favor of plaintiff-appellee cannot be

sustained in view of the conclusion we have arrived at above. Furthermore,

actual or compensatory damages must be duly proved (Article 2199, Civil

Code). Here, no proof of such damages was presented inasmuch as the case

was decided on a stipulation of facts and no evidence was adduced before

the trial court.

The basic fact appears in the stipulation submitted by the parties that said

plaintiff-appellee admitted having received a portion of the estate by virtue

of the extrajudicial partition agreement dated August 24, 1963. Such being

the case, defendant-appellant is apparently correct in his contention that the

lower court erred in not passing on his counterclaim and, consequently, in

not sentencing appellee to turn over to him his corresponding share of said

portion received by appellee under the void partition.

You might also like

- De Los Santos V Dela CruzDocument2 pagesDe Los Santos V Dela CruzTon Rivera0% (1)

- 43 Chua vs. CFI of Negros OccDocument5 pages43 Chua vs. CFI of Negros OccCharles Busil100% (1)

- Conde Vs Abaya Full and Digested CaseDocument10 pagesConde Vs Abaya Full and Digested CasePearl Regalado MansayonNo ratings yet

- Fleischer v. Botica Nolasco G.R. No.23241Document2 pagesFleischer v. Botica Nolasco G.R. No.23241Karen Selina AquinoNo ratings yet

- Court rules on joint will disputeDocument2 pagesCourt rules on joint will disputeandrea ibanezNo ratings yet

- Dizon-Rivera V Dizon - No. L-24561. June 30, 1970Document12 pagesDizon-Rivera V Dizon - No. L-24561. June 30, 1970Jeng PionNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 198664, November 23, 2016 People vs. Owen Cagalingan and Beatriz Cagalingan FactsDocument1 pageG.R. No. 198664, November 23, 2016 People vs. Owen Cagalingan and Beatriz Cagalingan FactsLara CacalNo ratings yet

- Wills Case Digest (Batch 2)Document34 pagesWills Case Digest (Batch 2)Juls RxsNo ratings yet

- Succession DigestDocument15 pagesSuccession DigestDavid Antonio A. EscuetaNo ratings yet

- Sps Charlito Coja Etc Vs Hon CA Et AlDocument8 pagesSps Charlito Coja Etc Vs Hon CA Et Alandrea ibanezNo ratings yet

- Collation Land Donation Siblings Intestate EstateDocument1 pageCollation Land Donation Siblings Intestate EstateapperdapperNo ratings yet

- De Borja V. de BorjaDocument1 pageDe Borja V. de BorjaJuan Carlos CodizalNo ratings yet

- Maria Uson's Inherited Land Rights UpheldDocument1 pageMaria Uson's Inherited Land Rights UpheldAthena SantosNo ratings yet

- Slides Successionrev2005Document182 pagesSlides Successionrev2005dempearl2315No ratings yet

- DE BORJA v. VDA DE BORJADocument2 pagesDE BORJA v. VDA DE BORJAjanine nenariaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Policronio Ureta Vs - VoidDocument14 pagesHeirs of Policronio Ureta Vs - VoidQuelnan BaculiNo ratings yet

- Dizon-Rivera vs. Dizon, 33 SCRA 554Document7 pagesDizon-Rivera vs. Dizon, 33 SCRA 554Marianne Shen Petilla100% (1)

- Seines v. EsparciaDocument3 pagesSeines v. EsparciaNina CastilloNo ratings yet

- 11 SCRA 422 Icasiano Vs IcasianoDocument3 pages11 SCRA 422 Icasiano Vs IcasianoMarie Mariñas-delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- 089 Aznar v. DuncanDocument4 pages089 Aznar v. DuncanPatricia Kaye O. SevillaNo ratings yet

- 06 Bonilla Vs Barcena, 71 SCRA 491Document2 pages06 Bonilla Vs Barcena, 71 SCRA 491Angeli Pauline JimenezNo ratings yet

- Acain vs. Iac, 155 Scra 100Document7 pagesAcain vs. Iac, 155 Scra 100AngelReaNo ratings yet

- Cruz v. Villasor, 54 SCRA 31 (1973)Document1 pageCruz v. Villasor, 54 SCRA 31 (1973)Angelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- Santos vs Manarang debt vs legacyDocument2 pagesSantos vs Manarang debt vs legacyCMGNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules on Case Involving Property Partition and Will InterpretationDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Rules on Case Involving Property Partition and Will Interpretationteryo expressNo ratings yet

- Dizon-Rivera v. Dizon DigestDocument2 pagesDizon-Rivera v. Dizon DigestJanina PañoNo ratings yet

- Compiled Cases - CompleteDocument67 pagesCompiled Cases - CompleteDeurod JoeNo ratings yet

- Sienes v. Esparcia ruling on sale by reservistaDocument1 pageSienes v. Esparcia ruling on sale by reservistasamontedianneNo ratings yet

- Rabadilla vs. CADocument1 pageRabadilla vs. CAKaren Patricio LusticaNo ratings yet

- Echavez vs. Dozen ConstructionDocument1 pageEchavez vs. Dozen ConstructionEm Asiddao-DeonaNo ratings yet

- Tayag v. Benguet Consolidated Inc.Document6 pagesTayag v. Benguet Consolidated Inc.RhoddickMagrataNo ratings yet

- Kalaw Vs MercadoDocument1 pageKalaw Vs MercadoEdu RiparipNo ratings yet

- Polly Cayetano vs. Cfi Judge Tomas T. Leonidas, 129 Scra 522 (1984)Document2 pagesPolly Cayetano vs. Cfi Judge Tomas T. Leonidas, 129 Scra 522 (1984)leslansanganNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Claro Laureta vs. IACDocument4 pagesHeirs of Claro Laureta vs. IACHannah Tolentino-DomantayNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of The Intestate Estate of The Late Kaw Singco (Alias Co Chi Seng) - SY OA vs. CO HO, 74 PHIL 239 (1943)Document1 pageIn The Matter of The Intestate Estate of The Late Kaw Singco (Alias Co Chi Seng) - SY OA vs. CO HO, 74 PHIL 239 (1943)leslansanganNo ratings yet

- Cuaycong V Cuaycong, 21 SCRA 1192Document4 pagesCuaycong V Cuaycong, 21 SCRA 1192PJFilm-ElijahNo ratings yet

- Pascual v. CIR, 166 SCRA 560 (1988)Document2 pagesPascual v. CIR, 166 SCRA 560 (1988)DAblue ReyNo ratings yet

- Lee VS RTCDocument22 pagesLee VS RTCAmor5678No ratings yet

- Rights of Heirs to Substitute for Deceased Party in Property CaseDocument2 pagesRights of Heirs to Substitute for Deceased Party in Property CaseGreta Fe DumallayNo ratings yet

- Tuason Vs TuasonDocument2 pagesTuason Vs TuasonPB AlyNo ratings yet

- Banco Do Brasil Vs Court ofDocument3 pagesBanco Do Brasil Vs Court ofJacqueline Pulido DaguiaoNo ratings yet

- Nera vs. Rimando (18 Phil 450)Document2 pagesNera vs. Rimando (18 Phil 450)KcompacionNo ratings yet

- Dela Cerna vs. Rebaca-PototDocument1 pageDela Cerna vs. Rebaca-PototMaria AndresNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument6 pagesCase DigestDiane AtotuboNo ratings yet

- Dela Cerna v. Rebaca-PototDocument2 pagesDela Cerna v. Rebaca-PototCarie LawyerrNo ratings yet

- Tuason Vs TuasonDocument1 pageTuason Vs TuasonPB AlyNo ratings yet

- In Re Estate of Johnson PDFDocument16 pagesIn Re Estate of Johnson PDFamicablesassyNo ratings yet

- Padura v. BaldovinoDocument2 pagesPadura v. BaldovinoVloudy Mia Serrano PangilinanNo ratings yet

- JAVELLANA VS LimDocument2 pagesJAVELLANA VS Limcmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Joint Will Probate RulingDocument1 pageJoint Will Probate RulinginxzNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds perpetual trusteeship of Doña Margarita Rodriguez estateDocument6 pagesSupreme Court upholds perpetual trusteeship of Doña Margarita Rodriguez estateNgan TuyNo ratings yet

- A. 2. Reyes vs. Barretto-DatuDocument1 pageA. 2. Reyes vs. Barretto-DatuchristianbunalesNo ratings yet

- Executive Order 227 Family Code - AmendmentsDocument1 pageExecutive Order 227 Family Code - AmendmentsspecialsectionNo ratings yet

- Guilas v. Judge of CFI inheritance disputeDocument2 pagesGuilas v. Judge of CFI inheritance disputeYsabelleNo ratings yet

- Estate of Hemady v. Luzon SuretyDocument11 pagesEstate of Hemady v. Luzon SuretyLeia VeracruzNo ratings yet

- Rabadilla Vs CADocument2 pagesRabadilla Vs CASopongco ColeenNo ratings yet

- Gallanosa V ArcangelDocument2 pagesGallanosa V ArcangelJeff SantosNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: C.A. Sobral For Appellant. Harvey & O' Brien and Gibbs & Mcdonough For AppelleeDocument3 pagesSupreme Court: C.A. Sobral For Appellant. Harvey & O' Brien and Gibbs & Mcdonough For AppelleeMp CasNo ratings yet

- Fleumer v. HixDocument2 pagesFleumer v. HixAziel Marie C. GuzmanNo ratings yet

- No. L-29192. February 22, 1971. GERTRUDES DE LOS SANTOS, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. MAXIMO DE LA CRUZ, Defendant-AppellantDocument12 pagesNo. L-29192. February 22, 1971. GERTRUDES DE LOS SANTOS, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. MAXIMO DE LA CRUZ, Defendant-AppellantEllis LagascaNo ratings yet

- Journal Entries and Financial StatementsDocument5 pagesJournal Entries and Financial StatementsArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- 1 Biodata TemplateDocument1 page1 Biodata TemplateIanusGwapitusNo ratings yet

- Afsgrshsgihg RFH JKNRGJKSRH Rhi KNJHRDocument1 pageAfsgrshsgihg RFH JKNRGJKSRH Rhi KNJHRArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Toa 34a-3Document1 pageToa 34a-3Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- 3rd Year ScheduleDocument2 pages3rd Year ScheduleArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Sec 14 - 23Document5 pagesSec 14 - 23Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Background InfoDocument1 pageBackground InfoArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Gov Acc Assignment JuanDocument5 pagesGov Acc Assignment JuanArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Literature Matrix Math AptitudeDocument3 pagesLiterature Matrix Math AptitudeArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Sec 5,6, 11-13Document3 pagesSec 5,6, 11-13Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Section 1Document3 pagesSection 1Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Break: 1.5 Hours Break: 1.5 Hours Break: 1.5 Hours Break: 1.5 HoursDocument1 pageBreak: 1.5 Hours Break: 1.5 Hours Break: 1.5 Hours Break: 1.5 HoursArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Sec 7, 8, 9Document2 pagesSec 7, 8, 9Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Sec 30-50 (Negotiation)Document10 pagesSec 30-50 (Negotiation)Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Juan Clyne A. Pray Jcba Company Corrales Avenue, Cagayan de Oro City Misamis Oriental, 9000Document6 pagesJuan Clyne A. Pray Jcba Company Corrales Avenue, Cagayan de Oro City Misamis Oriental, 9000Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Acc 5 Course OutlineDocument7 pagesAcc 5 Course OutlineArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Law OutlineDocument11 pagesLaw OutlineArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Actg 9 WAFI 1Document2 pagesActg 9 WAFI 1Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Fola ExercisesDocument1 pageFola ExercisesArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Architecture ComplationDocument9 pagesArchitecture ComplationArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Marketing Strategy PartialDocument3 pagesMarketing Strategy PartialArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Time Monday/Thurs DAY Tuesday/Frida Y Actg 8 BA 13.1: Break: 1.5 HoursDocument3 pagesTime Monday/Thurs DAY Tuesday/Frida Y Actg 8 BA 13.1: Break: 1.5 HoursArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Questioning BeingDocument2 pagesQuestioning BeingArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Income Tax Exercises IaDocument3 pagesIncome Tax Exercises IaArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- IAS12Document7 pagesIAS12Arvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- PASDocument1 pagePASArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- RaspunsuriDocument1 pageRaspunsuriRaluca RainNo ratings yet

- English Motivation OutlineDocument2 pagesEnglish Motivation OutlineArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- NBA 2K16 Keyboard MappingDocument1 pageNBA 2K16 Keyboard MappingArvin Glen BeltranNo ratings yet

- Automated Facilities Management v. PlanonDocument6 pagesAutomated Facilities Management v. PlanonPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Diamond vs. ChakrabartyDocument1 pageDiamond vs. ChakrabartySherwinBriesNo ratings yet

- Tense Jury Drama Explores Reasonable DoubtDocument3 pagesTense Jury Drama Explores Reasonable DoubtLucioJr AvergonzadoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Robert Tam, 4th Cir. (2011)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Robert Tam, 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court District of ColumbiaDocument26 pagesUnited States Court District of ColumbiaHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet

- Sales Cases On LeaseDocument53 pagesSales Cases On LeaseKarmaranthNo ratings yet

- Barratry Rules of Professional ConductDocument6 pagesBarratry Rules of Professional ConductDSTARMANNo ratings yet

- Court rules on copyright infringement caseDocument227 pagesCourt rules on copyright infringement caseMariel D. PortilloNo ratings yet

- Evidence PowerpointDocument18 pagesEvidence Powerpointpete malinaoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Appeal 200 of 2012Document7 pagesCriminal Appeal 200 of 2012cleyNo ratings yet

- Joanne Siegel Et Al v. Warner Bros Entertainment Inc Et Al - Document No. 276Document1 pageJoanne Siegel Et Al v. Warner Bros Entertainment Inc Et Al - Document No. 276Justia.comNo ratings yet

- CaseDigests Torts Chapter8Document17 pagesCaseDigests Torts Chapter8Mae TrabajoNo ratings yet

- Israeli Occupied TerritoriesDocument19 pagesIsraeli Occupied TerritoriesMohamed H100% (1)

- United States v. Henry Alberto Gomez-Ruiz, 931 F.2d 977, 1st Cir. (1991)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Henry Alberto Gomez-Ruiz, 931 F.2d 977, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Judicial System of Pakistan - Other - Miscellaneous Articles - HamariwebDocument4 pagesThe Judicial System of Pakistan - Other - Miscellaneous Articles - HamariwebNKhanJugnuNo ratings yet

- Nitafan V Cir G.R. NO. L-78780Document5 pagesNitafan V Cir G.R. NO. L-78780FrancisCzeasarChuaNo ratings yet

- Alliance For Nationalism and Democracy Vs COMELECDocument1 pageAlliance For Nationalism and Democracy Vs COMELECKarla BeeNo ratings yet

- Digest PROPERTY PossessionDocument22 pagesDigest PROPERTY Possessionamun dinNo ratings yet

- E-J-E-B-, AXXX XXX 122 (BIA Nov. 13, 2015)Document3 pagesE-J-E-B-, AXXX XXX 122 (BIA Nov. 13, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Serg Products Vs PCI LeasingDocument3 pagesSerg Products Vs PCI LeasingErika Angela Galceran100% (2)

- Jose Tan Chong Vs Secretary of Labor - September 16, 1947Document8 pagesJose Tan Chong Vs Secretary of Labor - September 16, 1947Lourd CellNo ratings yet

- Fair Trial of Accused in Criminal ProcedureDocument15 pagesFair Trial of Accused in Criminal ProcedurePrashaNt Tiwari100% (1)

- Jarron Draper v. Atlanta Public School District, 11th Cir. (2010)Document9 pagesJarron Draper v. Atlanta Public School District, 11th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Grammar For PetDocument3 pagesGrammar For Petjanaka chamindaNo ratings yet

- CTA upholds dismissal of CBC's claim for refund of taxes collected under invalid ordinancesDocument4 pagesCTA upholds dismissal of CBC's claim for refund of taxes collected under invalid ordinancesJun RiveraNo ratings yet

- US Vs Ang Tang HongDocument9 pagesUS Vs Ang Tang HongAngelie FloresNo ratings yet

- Instruction ManualDocument178 pagesInstruction ManualHarvey J90% (42)

- PRI Funding Epidemic ReportDocument24 pagesPRI Funding Epidemic ReportLeon R. Koziol100% (3)

- (HC) Todd Anthony Andrade v. James Yates - Document No. 5Document4 pages(HC) Todd Anthony Andrade v. James Yates - Document No. 5Justia.com100% (1)

- Lembaga Pembangunan Dan Lindungan Tanah (Land Custody and Development Authority) v. Crystal Realty SDN BHD & AnorDocument6 pagesLembaga Pembangunan Dan Lindungan Tanah (Land Custody and Development Authority) v. Crystal Realty SDN BHD & AnorAlae KieferNo ratings yet