Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CHA V DEC Decision, Dec. 5, 2016

Uploaded by

Watershed Post0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3K views18 pagesA judgment dismissing a lawsuit brought against the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation by the Catskill Heritage Alliance and other opponents of the Belleayre Resort project.

Original Title

CHA v DEC decision, Dec. 5, 2016

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA judgment dismissing a lawsuit brought against the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation by the Catskill Heritage Alliance and other opponents of the Belleayre Resort project.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3K views18 pagesCHA V DEC Decision, Dec. 5, 2016

Uploaded by

Watershed PostA judgment dismissing a lawsuit brought against the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation by the Catskill Heritage Alliance and other opponents of the Belleayre Resort project.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 18

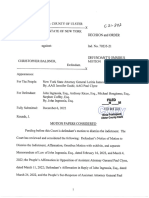

STATE OF NEW YORK

SUPREME COURT COUNTY OF ALBANY

CATSKILL "AGE ALLIANCE INC., KATHY NOLAN

as SECRETARY/TREASURER OF THE FRIENDS OF THE,

CATSKILLS PARK; PUA ASSOCIATES

BENJAMIN AND EDITH KORMAN; BEVERLY RAINONE;

MARY GOULD; KINGDON GOULD III; THORNE

GOULD; LYDIA BARBIERY; FRANK GOULD;

CANDIDA LANCASTER; ANNUNZIATA GOULD;

THALIA PRYOR; MELISSA GOULD and CALEB GOULD,

Petitioners, DECISION/JUDGMENT

-against- Index No. 5362-15

RIENo, 01-16-ST7541

NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION and

CROSSROADS VENTURES LLC,

Respondents,

‘APPEARANCES:

Bond, Schoeneck & King PLLC

For Petitioners

1111 Washington Avenue

Albany NY 12210-2211

Whiteman, Osterman & Hanna LLP

For Respondent Crossroads Ventures LLC

Once Commerce Plaza

Albany NY 12260

ERIC T. SCHNEIDERMAN

Attorney General of the State of New York

Norman Speigel and Andrew G. Frank, Esq, (Assistant Attorney General, of Counsel)

Attorney for Respondent New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

The Capitol

Albany, New York 12224-0341

RYBA,J.,

In 1999, respondent Crossroads Ventures LLC submitted applications for various permits

required for the proposed construction and development ofa combined hotel, spa and golf course

facility known as “The Belleayre Resort at Catskill Park”, situated on approximately 1,960 acres of

land owied by Crossroads in the adjacent towns of Shandaken and Middleton in the Catskill

Mountains. In June 2000, respondent New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

(hereinafier DEC) issued a positive declaration under the State Environmental Quality Review Act

(hereinafter SEQRA) (ECL §§ 8-0101 through 8-0117) determining that the proposed Belleayre

Resort may have a significant adverse impact on the environment, and thus required Crossroads

conduct an environmental review of the proposed project and to prepare a draft environmental

impact statement (hereinafter draft EIS)

In Jate 2003, Crossroads submitted a draft EIS for the original version of the project whieh

consisted of one economically integrated resort with two principle development components known

as Big Indian Plateaw'and Wildacres, The Big Indian Plateau development was to be situated on

approximately 1,242 acres of land and was to include Big Indian Country Club, consisting ofan 18

hole gold course, a clubhouse and 95 detached lodging units; Big Indian Resort and Spa, consisting

of a 150-room luxury hotel and spa with two restaurant and ballroom facilities; and Belleayre

Highlands, consisting of $5 detached lodging units, an activities center, swimming pool and tennis,

court. The Wildacres development was located on approximately 718 acres of land and included

Wildacres Resort, which offered amenities such as an 18-hole golf course and clubhouse, 250-room,

hotel, 13,000 square feet of retail space, three restaurants, a spa, a ballroom and a conference center;

the Wildemess Activity Center, which operated as a four-season facility utilizing pre-existing

buildings on the premises and offering a variety of recreational activities; and Highmount Estates,

which consisted of a 21-lot subdivision for single family homes.

‘After the draft EIS was accepted for public review, four days of legislative hearings were

conducted in January and February 2004 for the purpose of providing an opportunity for written

public comments on the proposed project. Thereafter, based upon concerns that the project may not

satisfy permitting standards, the DEC referred the project to its Office of Hearings and Mediation

Services whereupon an Administrative Law Judge conducted an issues conference for the purpose

of determining whether any substantive and significant issues impacting the environment should

advance to an adjudicatory hearing, At the extensive issues conference which spanned 18 days

between the period of May 2004 through August 2004, the participants presented the testimony of

dozens of witnesses and introduced thousands of pages of documentary evidence on various subjects

including stormwater management, visual impacts, community character impacts, and possible

alternative versions of the project.’

At the conclusion of the issues conference, the Administrative Law Judge issued a

ruling identifying various issues that he deemed to be substantive and significant and therefore

qualified for adjudication, including visual impacts, stormwater runoff management, impacts on

community character, and feasible project alternatives. On administrative appeal from that

determination, the then-Acting Commissioner delegated her decision-making authority to the Deputy

Commissioner, who issued an Interim Decision identifying six substantive and significantissues that

were advanced to adjudication, namely: 1) whether the water supply permit for the Big Indian

Plateau complied with applicable regulatory requirements; 2) dewatering and impacts on aquatic

"The entities that participated in the issues conference were Crossroads, DEC staff, the

New York City Department of Environmental Protection, the Coalition Watershed Towns,

Delaware County, the Towns of Middletown and Shandaken, the Town of Shandaken Planning

Board, and the Catskill Preservation Coalition and Sierra Club. ‘The Catskill Preservation

Coalition was comprised of 10 separate environmental groups including petitioner Catskill

Heritage Alliance Inc.

habitat; 3) stormwater related matters; 4) operational noise impacts on wildemess areas in the nearby

Catskill Forest Preserve arising from onsite activities at Big Indian Plateau; 5) visual impacts caused

by Big Indian Plateau, and 6) a supplemental evaluation of alternative project designs and layouts,

In the Interim Decision; the Commissioner also removed the issue of community character from

adjudication based upon a finding that no substantive and significant issue regarding community

character impacts existed.

After the Interim Decision was issued, the parties to the issues conference and the State of

‘New York entered into intensive negotiations in an attempt to develop a revised project design to

address and mitigate the adverse environmental impacts of the proposed project identified in the

Interim Decision. ‘These negotiations culminated in an Agreement in Principle (hereinafter AIP),

which was executed in September 2007 by the State of New York and all but four of the parties to

the issues conference, Under the terms of the AIP,

ssroads agreed to replace the originally

proposed Bellayre Resort development with a modified project that was intended to minimize the

potential for significant environmental impacts. The modified project completely eliminated the

Big Indian Plateau development and included significant modifications to the Wildacres

development including reconfiguration of the eastern portion of the development to minimize land

and steep slope disturbance, elimination of the 21-unit subdivision known as Highmount Estates,

elimination of one proposed golf course and organic management of the remaining course, and

enhanced storm water monitoring and management protocol. The AIP was executed with the

understanding that the modified project would require new or modified permit applications, the filing

? The terms of the AIP provided that approximately 1,200 acres of land comprising the

Big Indian Plateau was to be acquired by the State of New York for inclusion in the State Forest

preserve

ofa supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), and an additional period of public review

and comment. In view of the expected mitigation of the environmental concerns identified for

adjudication in the Interim Decision and the need for the submission of supplemental materials on

the modified project, Crossroads moved for an order suspending the adjudicatory hearing and staying

the pending motion for reconsideration of that portion of the Interim Decision which removed the

issue of community character from adjudication. Crossroads’ motion was granted.

In 2013, after completing the additional environmental studies contemplated by the AIP,

Crossroads supplied the DEC with a supplemental EIS (SEIS) and revised permit applications which

included additional environmental commitments and conditions that Crossroads agreed to

incorporate into the modified project after executing the AIP. As set forth in the SEIS, the modified

project consisted of Wildacres Resort, located on approximately 254 acres of the eastern side of the

project site, and Highmount Resort, located on approximately 237 acres on the westem side of the

project site. Following a legislative hearing allowing for public review and comment on the

modified project, in September 2014 the DEC issued a draft final EIS (FEIS) and preliminary final

permits reflecting responses to public comments and incorporating the project changes that

Crossroads agreed to after the signing of the AIP.

Thereafter, DEC staff filed « motion to eancel the adjudicatory hearing on grounds that the

modified project rendered all of the issues previously identified for adjudication moot or no longer

substantive and significant, and that any new issues raised by the modified project were not

substantive and significant so as to necessitate an adjudicatory hearing. DEC staff’ additionally

requested an order denying the previously suspended motion for reconsideration of that portion of

the Interim Decision which eliminated community character from the issues to be adjudicated. ‘The

motion was opposed by two parties to the issues conference, as well as by several of the petitioners

herein who were not parties to the issues conference but filed petitions for party status based upon

their ownership of land in the vicinity of the project. The procedural and substantive arguments

advanced in opposition to the DEC staff motion included claims that the Commissioner lacked

authority to consider the motions without an initial ruling from the Administrative Law Iudge (ALJ),

that the issues previously identified for adjudication were still substantive and significant, and that

the modified project presented new substantive and significant issues for adjudication including

significant visual impacts and stormwater management impacts that had not been mitigated

‘The Commissioner ruled on all pending motions and issues in a thorough and detailed 42-

page determination dated July 10,2015. Initially, the Commissioner determined that, inasmuch as

the motion by DEC staff was in essence one seeking reconsideration of the Interim Decision, he had

authority to rule on the motion rather than requiring it to be heard by an ALJ in the first instance.

‘The Commissioner further found that to the extent that DEC regulations required the motion to be

submitted to an ALJ in the first instance, DEC regulations granted him the authority to modify any

such rule in the interest of avoiding the prejudice, cost and delay that would result from remanding

the matter to an ALJ unnecessarily. Next, the Commissioner considered whether in light of the

significant modification of the project subsequent to the Interim Decision the six issues identified

therein remained adjudicable, and whether the proposed issues arising from the modified project

qualified for adjudication, After examining the materials in the record and noting that the SEIS

presented a comprehensive alternatives analysis explaining how the modified project achieved a

significant reduction in the overall size and scope of the project and mitigated or completely

climinated several environmental impacts of the original project, the Commissioner concluded that

the previously identified issues for adjudication were either moot or otherwise appropriately

addressed by the modified project. As for the newly proposed issues for adjudication relating to the

modified project, the Commissioner found that the issues were either untimely raised or that

petitioners failed to satisfy their burden of demonstrating that the issues were substantial and

significant, Finally, the Commissioner denied the motion for reconsideration on the issue of

community character based upon a finding that the Deputy Commissioner did not misapprehend the

relevant facts or misapply controlling law when removing the issue from adjudication. Accordingly,

the Commissioner granted the motion to cancel the adjudicatory hearing and remanded the matter

to DEC for acceptance of the FEIS and issuance of the final permits for the projects.

In this hybrid CPLR Article 78 proceeding and declaratory judgment action that later ensued,

petitioners seek a judgment annulling the Commissioner’s determination, remanding

the matter to an ALJ for rulings on the motion to cancel the adjudicatory hearing and other

matters, and an order revoking the final EIS and reopening the public hearing comment period.

‘As grounds for the requested relief, petitioners allege that the Commissioner's determination that

he was authorized to rule on the motion to cancel the adjudicatory hearing, as well as his

determination that the motion to cancel should be granted, was arbitrary and capricious and a

violation of agency rules,

Initially, in reviewing an administrative determination, the Court’s role is not to

reweigh the relevant factors and substitute its judgment for that of the ageney (see, Matter of

Gallo v State of N.Y. Off. of Mental Retardation & Dev. Disabilities, 37 AD3d 984, 985 [2007)),

but is limited to ascertaining whether the determination is arbitrary and capricious and, thus,

without a rational basis (see, Elacke v Onondaga Landfill Sys., 69 NY2d 355, 363 [1987]; Matter

of Warder v Board of Regents of Uniy, of State of NY, 53 NY2d 186, 194 [1981]; Port of

Oswego Auth. v Grannis, 70 AD3d 1101, 1103 [2010]; Matter of Grella v Hevesi, 38 AD3d 113,

116 (2007}), “An action is arbitrary and capricious when it is taken without sound basis in reason

or regard to the facts” (Matter of Peckham v Calogero, 12 NY34 424, 431 [2009]; see, Matter of

Pell v Board of Educ. of Union Free School Dis [Towns of Scarsdale & Mamaroneck,

Westchester County, 34 NY2d 222, 231 [1974)). In deciding whether an agency determination

has a rational basis, the Court must give great weight and considerable deference to an ageney’s

interpretation of its own regulations in areas ofits own expertise and must uphold any

construction given statutes and regulations by the ageney responsible for their administration that

is not irrational or unreasonable (see, Flacke v Onondaga Landfill Sys,, Inc,, 69 NY2d 355, 363

[1987]; Advanced Therapy v New York, State Educ, Dep't, 140 AD3d 1367, 1368 [2016], appeal

dismissed, leave denied _NY3d __ [Oct. 25, 2016]; Matter of Cooke Cir. for Leaming &

Dev. v Mills, 19 AD3d 834, 835 [2005] lv dismissed and denied 5 NY3d 846[2005]). Finally,

‘when a determination is supported by a rational basis, it must be sustained even if the reviewing

court would have reached a different result (see, Matter of Peckham v Calogero, 12 NY3d 424,

431 [2009]; CDE Elec., Inc. v Rivera, 124 AD3d 1178, 1180 [2015)).

‘The verified petition sets forth 13 causes of action challenging various alleged

procedural and substantive errors in the proceedings as grounds for annulment of the

Commissioner's determination. First addressing the various procedural errors alleged,

petitioners claim in their ninth cause of action that the Commissioner improperly placed various

motions in abeyance and thereby precluded them being fully and timely resolved, Inasmuch as

petitioners fail to provide any legal or factual basis for this argument in their supporting papers,

they have failed to satisfy their burden to demonstrate its validity. In any event, given the

‘Commissioner's inherent authority to resolve scheduling matters, and inasmuch as petitioners

have demonstrated no prejudice resulting from any delay in resolving the motions, this eause of

action does not furnish grounds to annul the Commissioner's determination. Similarly,

petitioners have failed to offer any legal or factual support for the 13 cause of action alleging

that DEC impermissibly included additional technical studies in the FEIS afler the publie

comment period was closed, In any event, the Court finds that DEC could have rationally

‘concluded that reopening the comment period was unnecessary under the circumstances

presented (see, Morse v Town of Gardiner Planning Bd., 64 AD2d 336 [1990]).

‘Turning to the remaining procedural irregularities alleged in the petition, the Court

discerns no basis to find that the Commi

joner abused his discretion in determining that he had

authority to rule on the DEC staff’s motion to cancel the adjudicatory hearing rather than remit

the matter to an ALJ for an initial determination. The Commissioner could appropriately elect to

treat the motion as one for reconsideration of the Interim Decision in light of the fact that the

modified project incorporated modifications aimed at mitigating the environmental concerns that

were identified for adjudication in the Interim Decision, Inasmuch as the Commissioner has

inherent authority to reconsider his own decisions, the motion was properly directed to his

attention. Moreover, as noted by the Commissioner, there is nothing in DEC hearing rules that

requires a motion for reconsideration of an Interim Decision to be directed to an ALI in the first

instance.

Further authority for the Commissioner's decision to rule on the motion to cancel the

adjudicatory hearing may be derived from Delegation of Authority Rule #14-02, which states that

ALIs are granted authority to act on the Commissioner's behalf, but clarifies that nothing

contained in such delegation of authority “shall limit [the Commissioner's) authority to convene

or conduct hearings or to render determinations or decisions.” Finally, a rational basis for the

Commis

ioner’s decision to hear the motion to cancel the adjudicatory hearing may be derived

from 6 NYCRR 624.6 (g), which provides that “to avoid prejudice to any party, all rules of

practice involving time frames may be modified by direction of the ALJ and, for the same

reasons, any other rule may be modified by the commissioner upon recommendation of the ALJ

or upon the commissioner's initiative” (6 NYCRR 624.6 [g] [emphasis supplied). Under the

circumstances, the Commissioner rationally concluded that ruling on the motion fo cancel rather

than remitting the matter to an ALJ was an appropriate course of action aimed at avoiding

unnecessary delay and expense in an already lengthy administrative process that extended over a

period of more than 16 years, Accordingly, the Court finds no reason to disturb the

Commissioner’s determination that he had authority to rule on the motion to cancel,

‘The Court will next consider the substantive arguments raised in the remainder of the

petition. Petitioners contend that the determination cancelling the adjudicatory hearing was

arbitrary and capricious and should be annulled because the Commissioner impropetly shifted the

burden of proof to the non-moving parties, improperly ruled that the issues identified for

adjudication in the Interim Decision no longer requized adjudication, and irrationally concluded

that the modified project raised no new issues requiring adjudication. In evaluating these claims,

it is important to note that an agency's assessment of the environmental impact of a particular

project, and the consequent determination to issue appropriate permits, will not be disturbed

unless it is predicated upon an error of law, is arbitrary or capricious, or constitutes an abuse of

10

discretion (see, CPLR 7803[3]; Matter of Town of Dryden v Tompkins County Bd, of

Representatives, 78 NY2d 331, 333 [1991 ; Matter of Pell v Board of Educ., 34 NY2d at 231

£1974]; Matter of Town of Charleston v Montgomery, Otsego, Schoharie Solid Waste Mgt

Auth., 235 AD2d 608 [1997], lv denied 89 NY2d 812 [1997]. “Moreover, where, as here, the

judgment of the agency involves factual evaluations in the area of the agency's expertise and is

supported by the record, such judgment must be accorded great weight and judicial deference * *

*° Glacke v Onondaga Landfill Sys., 69 NY2d 355, 363 [1987] [citations omitted); see, Reg'l

Action Grp. for the Env’t Inc. v Zagata, 245 A.D.2d:'798, 800 [1997]).

i

ly, the Court rejects the notion that the Commissioner improperly allocated the

burden of proof to petitioners, With regard to DEC’s staff motion to cancel the adjudicatory

hearing on the issues identified for adjudication in the Interim Decision, the Commissioner ruled

that DEC staff bore the burden to demonstrate that such issues no longer qualified for

adjudication. As for any new environmental issues created by the modified project, the

Commissioner ruled that petitioners bore the burden to establish that these proposed issues were

substantive and significant and thus warranted adjudication, The Court discerns no abuse of

discretion in this regard. Notably, 6 NYCRR § 624.4 9 (c) (1) (iii) provides that “in situations

where the department staff has reviewed an application and finds that a component of the

applicant’s project * * * conforms to all applicable requirements of a statute or regulation, the

burden of persuasion is on the potential party proposing any issue related to that issue to

demonstrate that itis both substantive and significant.” A plain reading of this language clearly

supports the Commissioner's decision to appropriately place the burden upon petitioners, the

parties proposing the claimed issues for adjudication, to establish that the proposed

uW

environmental issues ereated by the modified project were substantive and significant,

The Court will next address the claim that the Commissioner erroneously found that

certain issues identified for adjudication in the Interim Decision were either moot or were no

longer substantive and significant by virtue of the changes effectuated by the modified project.

Initially, petitioners concede that all issues relating exclusively to development at the Big Indian

Plateau have been rendered moot by the elimination of that component from the modified

project. Petitioners accordingly limit their challenge to the Commissioner's determination that

no adjudicatory hearing was necessary on the previously identified issue of feasible altemative

project designs and layouts. As for new issues arising out of the modified project, petitioners

contend that the Commissioner erred in finding that no substantive and significant issues for

adjudication existed with regard to the issues of stormwater management and visual impacts.

‘The determination of whether an environmental issue is substantive and significant

requiring an adjudicatory hearing is a matter left to the Commissioner, whose finding will not be

disturbed absent a showing that “it is predicated upon an error of law, is arbitrary or capricious,

or represents an abuse of discretion’ ” (Saratoga Water Servs, v Zagata, 247 AD2d 788, 789-790,

669 [1998], quoting Matter of Regional Action Group for Envi. v Zagata, 245 AD2d 798,

800,[1997], lv denied 91 NY2d 811 [1998]; see, Matter of Eastern Niagara Project

Alliance v New York State Dept, of Envtl. Conservation, 42 AD3d 857, 861 [2007]).

Furthermore, a proposed issue may be found to be “substantive” only where “there is sufficient

doubt about the applicant's ability to meet statutory or regulatory criteria applicable to the

project” (6 NYCRR 624.4 [c] [2]). Am issue may be deemed significant “if it has the potential to

result in the denial of a permit, a major modification to the proposed project or the imposition of

12

[additional] significant permit conditions” (6 NYCRR 624.4 [c][3]; see, Matter of E:

‘Niagara Project Power Alliance v, New York State Dept. of Envtl. Conservation, 42 AD3d 857,

861 [2007)). In order to demonstrate entitlement to an adjudicatory hearing, petitioners were

required to substantiate their concerns with an offer of proof explaining the basis of their claims

and identifying specific grounds that would warrant the denial or significant limitation of the

pert (see, Raritan Baykeeper, Inc, V Martens, 142 A.D.3d 1083 [2016]). “Mere expressions of

general opposition to a project are insufficient grounds for holding an adjudicatory public hearing

on.a permit application” (6 NYCRR 621.8[d]; see, E, Niagara Project Power All, v St

Envtl. Conservati

ion, 42 AD3d 857, 861 [2007]); Matter of Citizens for Clean Air v New York

State Dept. of Envtl. Conservation, 135 AD2d 256, 261 [1988], appeal dismissed 72 NY2d 853

[1988] ). In evaluating whether the determination to deny an adjudicatory hearing is rational, the

Court must not reweigh the underlying factors or the desirability of any action and is precluded

from substituting its judgment for that of the agency (see, Matter of Gallo v State of N.Y., Off. of

Mental Retardation & Dev. Disabilities, 37 AD3d 984, 985 [2007]; E. Niagara Project Power

All.v, State Dep't of Envtl. Conservation, 42 AD3d at 861 [2007]). Rather, the determination

not to adjudicate an issue will be upheld and a substantive and significant issue will not be found

if the determination is reasonable and supported by the record” (see, Gracie Point Cmty.

ex rel, Ard v NY. State Dep't of Envtl, Conservation, 92 AD3d 123 [2011]).

A review of the record leads the Court to conclude that the Commissioner did not abuse

his discretion in determining that there were no substantive and signi

cant issues warranting

adjudication. First addressing the denial of the motion to rec

ider the decision to remove the

issue of community character from aduidication, the Deputy Commissioner’s finding that an

B

adjudicatory hearing was unnecessary was premised upon the considerable deference that must

be afforded to the standard for community character established by local land use plans, and upon

the fact that the record already contained more than sufficient information as to community

character by virtue of the three-day evaluation of the issue during the issues conference, In

evaluating the motion for reconsideration, the Commissioner declined to disturb this

determin

jon, finding that the Deputy Commissioner did not misapprehend the relevant facts or

misapply controlling law in reaching his determination that an adjudicatory hearing was

unnecessary. Here, petitioners have not demonstrated that the Deputy Commissioner

misinterpreted the facts, applied an incorrect legal standard or failed to appropriate separate

consideration to community character issues. Accordingly, the Court declines to disturb the

Commissioner’s determination denying the motion for reconsideration (see, Foley v Roche, 68

AD2d 558 [1979]).

Next, there is no merit to petitioners’ argument that the Commissioner abused his

discretion in concluding that whether feasible alternatives to the proposed project existed was

not an issue that merited adjudication. The Interim Decision identified the feasible alternatives

issue as one requiring adjudication and, accordingly, required Crossroads to provide a SEIS

detailing the environmental impacts of alternative layouts on Wildacres Resort and Big Indian

Plateau, specifically an east resort [Big Indian Plateau] and west resort [Wildacres] alternative, a

one golf course and one hotel complex alternative, and any feasible smaller-scale project and

layout alternatives. Petitioners do not contest that the Commissioner rationally concluded that

the complete elimination of the Big Indian Plateau aspect of the development from the modified

project rendered moot the directive to consider altemative layouts of Big Indian Plateau,

4

However, petitioners argue that the Commissioner abused his discretion in determining that the

modified project adequately addressed the Interim Decision’s directive to consider other smaller-

scale project alternatives and layout alternatives and that no adjudicatory hearing was required on

these issues. Specifically, petitioners assert that substantial and significant issues were raised

regarding the feasibility of a “Wildacres Resort only” alternative, ic., the complete elimination of

Highmount Resort from the project, and that the Commissioner therefore abused his diseretion int

caneelling the adjudicatory hearing on the issue of feasible alternatives,

The record clearly reveals a rational basis for the Commissioner’s conclusion that no

substantive and significant issues remained for adjudication regarding feasible project

alternatives inasmuch as the SEIS prepared by Crossroads for the modified project satisfactorily

analyzed the environmental impact of the feasible alternative issues directed by the Interim

Decision. Based upon a review of the record, itis evident that the Commissioner rationally

found that the SEIS presented a comprehensive alternatives analysis comparing the type and

magnitude of the environmental impacts of the original project to those of the modified project,

while also underscoring the reduction in overall size and scope of the modified project as a

whole. As for the “Wildacres Resort only” project alternative, the Commissioner’s finding that

this proposed alternative did not present a substantial and significant issue for adjudication was

rationally based upon the environmental analysis set forth in the SEIS, which revealed that

eliminating the Highmount Resort from the project would only modestly reduce negative

environmental impacts while simultaneously rendering the remainder of the entire project

economically unfeasible. Although petitioners’ expert offered a contrary opinion that a

“Wildacres Resort only” alternative was economically feasible, this does not automatically raise

15

a substantive and significant issue for adjudication inasmuch as economic feasibility need not be

considered under SEQRA (see, Matter of Kirque] Development v Planning Bd. of Town of

Cortlandt, 96 Ad3d 754, 755 [2012], lv denied 19 NY3d 813 [2012}). In any event, the fact that,

a different determination could have been made on the basis of conflicting evidence does not

‘warrant judicial interference where the challenged determination has a rational basis (see,

‘Town of Preble v Zagata, 263 AD2d 833, 835 [1999]). The Commissioner’s determination that

the issue of feasible project alternatives was adequately addressed and did not warrant an

adjudicatory hearing was based upon a complete review of a well-developed record and the Court

declines to substitute its judgntent for that of the Commissioner (see, Reg'l Action Grp. for the

Env't Ine, v, Zagata, 245 AD2d 798, 800 [1997]; Matter of Gracie Point Comm. Council v New

‘York State Dep't of Envil, Conservation, 92 AD3d 123, 129, Iv denied 19 NY3d 807 (2011).

Having addressed the Commissioner's determination with respect to the issues previously

identified for adjudication, the Court will now turn to the new environmental issues alleged to

have been created by the modified project. Petitioners contend that the Commissioner

inrationally determined that the modified project did not give rise to any new substantive and

significant impacts requiring adjudication, arguing that an adjudicatory hearing is warranted on

issues relating to stormwater management and visual impacts of the modified project. With

regard to stormwater management issues, petitioners assert that the Commissioner erred in

excluding from adjudication potential issues relating to the increased capacity of culverts on the

Highmount development and the increased volume of runoff caused by extreme weather events.

According to petitioners, these issues were substantive and significant as they relate to properties

adjacent to and downstream from the Highmount development which would potentially face

16

substantial damage from runoff in the event of a high intensity rainfall. In rejecting this

argument, the Commissioner initially noted that petitioner failed to identify any legal authority

requiring evaluation of these issues. In any event, the Commissioner based his finding that

stormwater management did not present a substantive and significant issue for adjudication upon

his review of relevant studies and information, including the fact that the proposed stormwater

management system would achieve runoff rates equal to or below existing conditions and

satisfied the applicable requirements for mitigation of storm events set forth in the 2010 New

York State Stormwater Management Design Manual and New York City Department of

Environmental Protection requirements. The factual assessments performed by the

Commissioner in rendering his determination required highly specialized expertise and are

entitled to great deference and, notably, it is not the function of this Court to substitute its

judgment for that of the Commis

jioner or to conduct a de novo review of every potential

environmental impact raised by petitioners (see, Aldrich v Pattison, 107 AD2d 258 [1985)).

Inasmuch as the Commissioner's determination is supported by a reasoned analysis of the

relevant evidence, the Court finds no basis to disturb it,

Finally, petitioners contend that the Commissioner irrationally found no issue for

adjudication with regard to visual impacts of the modified project upon the neighboring Galli-

Curci Mansion, which is owned by petitioner PUA Associates LLC. Specifically, petitioners

contend that the Commissioner failed to consider their expert evidence disclosing significant,

visual impacts and erroneously relied upon the finding of the Office of Parks, Recreation and

Historic Perseveration (hereinafter OPRHP) that no adverse impacts would result to the historic

”

property. ‘The record reveals that in rendering his determination, the Commissioner did not rely

solely on the OPRHP’s finding of no adverse impact, but also considered the statements of

petitioners’ expert, the results of the visual impact assessment performed by DEC staff that

revealed no significant visual impact issues, and additional visual impact reviews detailed in the

FEIS which demonstrates that certain intervening topography would visually screen the modified

project. Under these circumstances, the record clearly demonstrates a rational basis for the

Commissioner’s determination that petitioners failed to raise a substantive and significant visual

impact issue that would require adjudication.

To the extent that petitioners’ contentions have not been specifically addressed herein,

they have been reviewed and found to be lacking in merit,

For the foregoing reasons, it is

ORDERED AND ADSUDGED that petitioners’ request for relief is denied and the

petition is dismissed, without costs.

This memorandum constitutes the Decision and Judgment of the Court. The original

Decision and Judgment is being returned to the attorney for the respondents, The below

referenced original papers are being transferred to the Albany County Clerk, The signing of the

Decision and Judgment shall not constitute entry or filing under CPLR 2220. Counsel is

not relieved from the provision of that rule regarding filing, entry or notice of entry.

SO ORDERED.

ENTER,

Dated: December 5, Qole

HON. CHRISTINA L. RYBA

Supreme Court Justi

You might also like

- Kingston Rent Control Appellate Court DecisionDocument9 pagesKingston Rent Control Appellate Court DecisionDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Joseph Maloney's Affidavit in SupportDocument12 pagesJoseph Maloney's Affidavit in SupportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Filed by Charles Whittaker Against Donald Markle and Joseph MaloneyDocument9 pagesLawsuit Filed by Charles Whittaker Against Donald Markle and Joseph MaloneyDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- NY AG Report On Saugerties Police Officer Dion JohnsonDocument15 pagesNY AG Report On Saugerties Police Officer Dion JohnsonDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Sales Tax Revenues 2022Document2 pagesUlster County Sales Tax Revenues 2022Daily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Fire Investigators Report On Oct. 10, 2023, Fire in KerhonksonDocument19 pagesFire Investigators Report On Oct. 10, 2023, Fire in KerhonksonDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit Filed by Frank and Pam Eighmey Against Town of WoodstockDocument46 pagesLawsuit Filed by Frank and Pam Eighmey Against Town of WoodstockDwayne Kroohs100% (1)

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger's Open LetterDocument2 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger's Open LetterDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Out of Reach 2023Document17 pagesOut of Reach 2023Daily Freeman100% (1)

- Ulster County Solar PILOTs Audit - Review of Billing and CollectionsDocument7 pagesUlster County Solar PILOTs Audit - Review of Billing and CollectionsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Vassar College Class Action ComplaintDocument25 pagesVassar College Class Action ComplaintDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County First Quarter 2023 Financial ReportDocument7 pagesUlster County First Quarter 2023 Financial ReportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan ResponseDocument3 pagesUlster County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan ResponseDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- HydroQuest UCRRA Landfill Siting Report 1-05-22 With MapsDocument29 pagesHydroQuest UCRRA Landfill Siting Report 1-05-22 With MapsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Tyrone Wilson StatementDocument2 pagesTyrone Wilson StatementDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- New York State Senate Committee Report On Utility Pricing PracticesDocument119 pagesNew York State Senate Committee Report On Utility Pricing PracticesDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Real Property Tax Audit With Management Comment and ExhibitsDocument29 pagesReal Property Tax Audit With Management Comment and ExhibitsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger, Municipal Leaders Letter Over Rail SafetyDocument3 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger, Municipal Leaders Letter Over Rail SafetyDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Central Hudson Class Action LawsuitDocument30 pagesCentral Hudson Class Action LawsuitDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Schumer RRs Safety LetterDocument2 pagesSchumer RRs Safety LetterDaily Freeman100% (1)

- Letter To Ulster County Executive Regarding Request For Updated Emergency PlanDocument1 pageLetter To Ulster County Executive Regarding Request For Updated Emergency PlanDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger Open Letter On County FinancesDocument2 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger Open Letter On County FinancesDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Terramor Application Withdrawa February 2023Document1 pageTerramor Application Withdrawa February 2023Daily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Central Hudson Response To Public Service Commission ReportDocument92 pagesCentral Hudson Response To Public Service Commission ReportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Judge Ruling Dismisses Murder Charge Against State TrooperDocument23 pagesUlster County Judge Ruling Dismisses Murder Charge Against State TrooperDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Public Service Investigation Report On Central HudsonDocument62 pagesPublic Service Investigation Report On Central HudsonDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Ulster County Executive Jen Metzger Order Regarding Implementation of The New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection ActDocument4 pagesUlster County Executive Jen Metzger Order Regarding Implementation of The New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection ActDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Democrats' Lawsuit Seeking New Ulster County Legislative MapsDocument21 pagesDemocrats' Lawsuit Seeking New Ulster County Legislative MapsDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- 2022 Third Quarter Financial ReportDocument7 pages2022 Third Quarter Financial ReportDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Jane Doe v. Bard CollegeDocument55 pagesJane Doe v. Bard CollegeDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)