Professional Documents

Culture Documents

An Outsider Is Always An Outsider

Uploaded by

Jafar KizhakkethilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

An Outsider Is Always An Outsider

Uploaded by

Jafar KizhakkethilCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

ISSN: 1533-9114 (Print) 2150-5403 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcad20

An Outsider is Always an Outsider: Migration,

Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

Lucille Lok-Sun Ngan & Kam-Wah Chan

To cite this article: Lucille Lok-Sun Ngan & Kam-Wah Chan (2013) An Outsider is Always an

Outsider: Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia, Journal of Comparative

Asian Development, 12:2, 316-350, DOI: 10.1080/15339114.2013.801144

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15339114.2013.801144

Published online: 18 Jun 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 589

View related articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcad20

Download by: [117.247.176.240]

Date: 23 November 2016, At: 20:38

Journal of Comparative Asian Development, 2013

Vol. 12, No. 2, 316350, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15339114.2013.801144

An Outsider is Always an Outsider: Migration,

Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

Lucille Lok-Sun NGAN

Social and Policy Research Unit, Department of Social Sciences,

The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong

Kam-Wah CHAN

Department of Applied Social Sciences,

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Abstract

The dynamics of social exclusion and inclusion of certain groups of citizens

and migrant workers is a complex and multi-dimensional process, which is

shaped by institutional frameworks as well as informal practices. While

some of these frameworks are justied by economic rationality, migrants

with low socio-economic background are often excluded from aspects of

labour and social protection, therefore reinforcing hegemonic ideas about

insiderness and outsiderness. This paper argues that how readily government-enforced policies embrace migrants is crucial to the reinforcement

of social stratication. Specically, the article examines the immigration,

labour and social security policies aimed at low-skilled migrant workers

in Seoul and Taiwan, low-skilled cross-border migrants in Hong Kong

and rural to urban migrants in Beijing. It highlights how policies veer

towards the exclusionary when targeted towards low-income migrant

groups from Southeast and East Asia, which manifest racial discrimination

against them. The accumulation effect of their disadvantaged status has a

detrimental impact on both migrant workers quality of life and cohesion

of society as a whole.

* Correspondence concering this article may be addressed to be author, Lucille Lok-Sun Ngan, at:

llsngan@ied.edu.hk

2013 City University of Hong Kong

316

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

317

Keywords: Migration; social exclusion; marginalization; social policy;

labour policy; social stratication; social security; social assistance; lowskilled migrants; cross-border migrants; internal migrants; outsider; East

Asia; Hong Kong; Beijing; Seoul; Taipei

Outsiders and Insiders

In the age of globalization, immigration and its effects on the changing

urban social landscape have intensied the social distinction between outsiders and insiders, affecting the order of social divisions in host

societies. Such distinction is one of differences and similarities based on

an awareness of social acceptance and exclusion involving a social

process of othering. Insiderness and outsiderness is a social experience

that is not just conned to ethnic groups as it exists in all communities

and societies, between those who belong, who are part of us, and those

who may be experienced as foreign or alien (Billington et al., in Crow,

Allan, & Summers, 2001, p. 30). However, as incomers, both international

and internal migrants are particularly subject to being classied as outsiders

since their social status is often attached to criteria such as length of local

residence, ethnicity, place of birth and shared history. Lim (2010, p. 55)

notes the general contempt of domestic society towards outsiders:

Outsiders (especially poor outsiders) are considered to be serious

threats to social cohesion and a danger to the livelihood and very

lives of real citizens; as best, they are seen as a necessary evil.

As such, the marginalization, exploitation and outright oppression

of outsiders is either ignored or condoned by the larger society.

With the globalization of migration and urbanization, most countries do

not host a single category of migrants but receive a diverse range (BentonShort, Price, & Friedman, 2005). In migration research and policy, different

types of migration are generally placed into two categories, international

migration and internal migration, which involve permanent and temporary

movements. International migration includes low-skill and professional

high-skilled labour, family/spouse reunion, business migration and refugees.

Generally, international migrants who move from low-income to middle- and

high-income countries are seeking for better ways to provide for their

families or to escape unemployment, war, or poverty in their countries of

origin (Benach, Muntaner, Delclos, Menendezl, & Ronquillo, 2011).

318

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

In the past 20 years, temporary guest-worker programmes directed at

low-income and low-skilled foreign migrant workers which systemically

discourage their settlement have been particularly popular in some industrialized East Asian countries. In places such as Taiwan, South Korea, Hong

Kong, Japan and Singapore, the recruitment of overseas migrant workers to

ll in gaps in the host countrys labour market has led to a structural reliance

on foreign workers (Tierney, 2007; Tseng & Wang, 2011). Guest-worker

programmes, such as those in South Korea and Taiwan, that bind migrant

workers to the same employer and require them to leave the country

immediately after the termination of their contract, in practice, have the

effect of excluding migrants from equal treatment rights and social integration. The legal frameworks that regulate the low-income migrants are

often much more stringent than the high-income groups (Stahl, 2003).

According to an International Labour Organization (ILO, 2007) report on

global discrimination, [n]ational migration policies are more inclined to

provide for equal opportunities and treatment between nationals and

migrant workers in high-skilled positions than those in unskilled and

low-status jobs. For example, high-skilled workers are usually given

more incentives to become permanent residents than the low-skilled, who

are made up of a high proportion of Southeast and East Asians (Hugo,

2009).

In the aspect of health and work, compared to high-skilled migrants

who may suffer from some potential health risks, studies have shown that

low-skilled migrant workers are more prone to contracting diseases

unknown to their place of origin (Grondin, Weekers, Haour-Knipe, Elton,

& Stukey, 2003, pp. 8593). Low-skilled migrants are also often exposed

more to potentially health-damaging work environments than locals

because of work exploitation. They are often recruited as the low-skill

labour force that lls the 3-D jobs (dirty, dangerous and demeaning)

that locals eschew, despite often being over-qualied for these positions

(Fernandez & Ortega, 2008; Hugo, 2009; Kim, 2004; Rhee, Lee, & Cho,

2005).

The second type of migration, internal migration involving migratory

movements within national boundaries, has generally received less scholarly attention than international migration. The main reason for the lack

of focus is that the movements of internal migrants are within national

boundaries which presuppose equal social rights and social protection;

nevertheless, social exclusion at the social level exists. The exclusionary

treatment of internal migrants can be demonstrated through the experience

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

319

of rural to urban migrants in Mainland China. The number of internal

migrants in Mainland China has increased dramatically over the past 20

years from about 26 million in 1988 to 126 million in 2004 (Deshingkar,

2006). Most of these internal migrants, also known as the oating population, are circular migrants who retain strong linkages with their families

in the rural area. As a number of studies have highlighted, while these

internal migrants share the same Chinese nationality as their urban local

counterparts, their limited access to welfare services and social participation

is a result of their migrant status (Chui, 2002; Fan, 2002; Law & Lee, 2006).

The situation in the Hong Kong SAR is unique as it is a special administrative region of the Peoples Republic of China, under the principle of one

country, two systems, it runs on economic and political systems different

from those of Mainland China. Nevertheless, new arrivals1 from Mainland

China can still be considered internal migrants as Hong Kong is a part of

China. Therefore, as Crow et al. (2001) argue, operating in a simple

insider/outsider or us/other dichotomy is problematic as there is no single

pattern or xed set of characteristics that delineates the exclusion of different migrant groups within a society.

The structure of social policies is an embodiment and expression of the

state towards constituent ethnic aggregates which has reinforcing effects on

the insider/outsider dichotomy. The dynamics of the inclusion and exclusion of migrants therefore is embedded within a wider context shaped by

power relations, institutional arrangements and cultural values, and can

be associated with labour protection, access to social protection and

social participation. Policies driven by the state are a mechanism that contributes to the reinforcement of social divisions between foreign migrants

and local citizens. At the same time, the states categorization of immigrants

is often based on historically situated social constructions of ethnicity, race,

class and gender, which are inuenced by hegemonic ideas of belongingness. The combined effect means that social policies directed at lowincome international migrants and internal migrants (particularly in the

case of China) tend to situate them in a relatively disadvantaged position.

Unequal treatment because of their status as foreigners or non-citizens

affects not only their quality of living and life chances but also the social

cohesion of society.

1 New arrivals from Mainland China refers to former Mainland China residents who entered

Hong Kong with a one-way exit permit for settlement and have resided in Hong Kong for

less than seven years.

320

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

As will be discussed, the different treatment between professional and

low-skilled foreign workers in Taiwan and South Korea, and the disparity in

social welfare between internal migrants and local citizens in Mainland

China and Hong Kong, are examples of the establishment of social divisions through institutional power. The differences in immigration and

social policies towards different categories of migrants, particularly those

from Southeast and East Asian societies, are driving mechanisms that contribute to the stigmatization of low-income immigrants as outsiders.

In examining international migration development in the Asia region,

research has primarily focused on migrants remittances, brain drain, diaspora development and temporary migration (Asis, Piper, & Raghuram,

2010). The different uses of remittances in addressing inequalities or

poverty have been well debated (see for instance, Athukorala, 1992,

1993; Ford, Jampaklay, & Chamratrithirong, 2009; Jha, Sugiyarto, &

Vargas-Silva, 2010; Lee, Sukrakarn, & Choi, 2011). Migration studies in

Asia have also focused on brain drain to the developed Western world

(see for instance, Broaded, 1993; Teng, 1994) as well as reverse brain

drain to the developing world (Montgomery & Rondinelli, 1995). Studies

on diasporas are primarily explored through a cultural and social analysis

(see for instance, Bao, 2004), where the focus is often on less tangible institutional factors related to ethnicity. There is a wealth of literature on temporary international labour migration (Abella, 2006; Abella, Park, & Bohning,

1995; Bohning, 1996; Tseng & Wang, 2011; Wickramasekara, 2002).

Areas that have received relatively less interrogation are the experiences of disadvantaged groups such as internal migrants and foreign

spouses who generally have low socio-economic status. Only recently

has international marriage been added to the research agenda in Taiwan

(Sheu, 2007; Tsai, 2011; Tsay, 2004; Wang & Chang, 2002), South

Korea (Cho, 2010; Kong, Yoon, & Yu, 2010; Lee, 2008; Lim, 2010) and

Japan (Nakamatsu, 2003; Piper, 1997). Because of the extent and impact

of internal migration on economic growth in Mainland China since the

1970s, it has been more studied than international migration (Fan, 2002;

Hong et al., 2006; Li, 2005; Liang, Por Chen, & Gu, 2002; Wan, 1995).

Much less emphasis has been placed on the impact of social policies

enforced by the state which contributes to the social order of stratication

including gender inequality of low-skilled migrant workers. In particular,

not much has been written about the collective experience of these disadvantaged groups as a whole and the inter-relationship between different categories of migrants. One exception includes the work of Piper and Roces

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

321

(2003), which explores the blurring boundaries between labour migration

and international marriage of East Asian men and Southeast Asian women.

In this paper, we argue that state-enforced policies often construct

social exclusions of disadvantaged migrant groups, reinforcing patterns of

disparity within society. To demonstrate this, we examine the impact of

immigration and social policies on the dynamics of social exclusion and

inclusion between locals and incomers in four East Asian societies. Specically we focus on the experience of low-skilled foreign migrant workers in

Seoul and Taipei, and low-skilled internal migrants in Beijing and Hong

Kong. We rst outline the ways in which immigration policies in each

society tend to veer towards the exclusionary when aimed at migrants

with low socio-economic status. Secondly, we explore migrants experiences of marginalization in terms of their levels of access and social participation through policies related to social protection and labour welfare.

Before we begin our discussion, we provide below the methodological framework of this study.

Methodology

Data for this paper emerged from a larger international comparative study

that examined issues relating to the sustainability and governance of

social welfare and the impact on citizenship, well-being and social cohesion

in four East Asian societies, namely Beijing, Hong Kong, Taipei and Seoul.

Concerning the comparability between the four cities, we focused mainly

on issues in the designated cities instead of the whole country, as it

would be too complicated to handle in one study. The study highlighted

gender and the life-course as key variables in understanding the dynamics

of governance, citizenship and social policy.

In order to understand the challenges and contradictions confronting

these four cities, we gathered in-depth qualitative data through two main

strategies; rstly, interviews with key actors in the policy-making process

and secondly, focus groups with local citizens and migrants. The multilevel data collection method adopted aimed to enhance our understanding

about the social reality experienced by local citizens and migrants.

Fieldwork data collection was conducted between December 2008 and

July 2009. Organization interviews included individuals from government

departments responsible for areas of labour, social welfare, womens

rights and ethnic relations, advisory bodies and think tanks for the govern-

322

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

ment, trade unions, academia, non-government organizations (NGOs) and

non-prot organizations (NPOs). The selection aimed to represent stakeholders of the policy-making process from local and national levels

within each city. In Hong Kong we conducted 12 interviews with key informants from local organizations, in Seoul 17, in Taipei 16 and in Beijing 11

(see Table 1 for details of sectors of organization interviews).

In order to understand the dynamic inter-relationships between citizenship and social inequalities, we also conducted focus groups involving local

citizens and specic low-income migrant groups. Participants were

recruited from religious organizations, community associations, social

groups, schools, universities and volunteer associations. Eight focus

groups which included six citizen groups at different stages of the lifecourse (under 30 years, 3145, and 46 or above) and two migrant groups

were conducted in each city. The focus on specic migrant groups

enabled us to better understand the context-specic issues around migration

and citizenship that emerged from a dynamic historical, social, economic

and political trajectory in each city. Men and women were interviewed separately to ensure capturing the voices and opinions of all respondents. This

enabled the different patterns of interaction with policy areas and the different impacts of policy change to be identied in terms of both gender

and age.

We selected a specic low-skilled migrant group in each city due to

their key position in migration debates in their respective locations and

because their lack of institutional labour protection and citizen rights represented a pattern of social exclusion. Low-skilled migrants were the

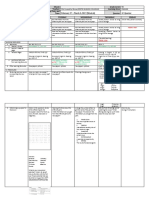

Table 1 Sectors of Organizations Interviewed

Hong Kong

Beijing

Taiwan

Seoul

Government departments

Advisory bodies/Think tanks

Trade unions

NGOs and NPOs

Academia

Private organizations

12

11

16

17

Total

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

323

focus of our study. In Taiwan and Seoul, our emphasis was on overseas

blue-collar migrant workers as there has been an increasing demand to

import foreign workers into the country since the 1980s due to labour

shortages in certain segments of the economy.

In Hong Kong, while the major demand for importation of foreign

workers is for domestic helpers, mainly from Indonesia and the Philippines,

the more conspicuous migrant issue concerns new arrivals from Mainland

China. The one-way permit (OWP) scheme, enforced since the 1990s,

has created much social tension between the locals and new arrivals. As

noted earlier, to a certain extent these migrants are internal migrants as

they are moving from one region in China to another.

Unlike Taiwan and South Korea, where there is a large demand for the

importation of foreign workers, in Beijing, the internal migration of workers

from rural to urban areas and their social welfare have been the major concerns of domestic policies. Therefore, in Beijing our focus was on internal

rural to urban migrants.

The qualitative nature and limitation in the sample size of our study

mean our ndings would not be representative of all experiences of lowskilled migrant workers in Seoul, Taipei, Hong Kong and Beijing. In this

respect, rather than making general conclusions about the social experience

of the community, this study explored the uncharted social realities of

specic disadvantaged migrant groups in each city through the everyday

experiences of migrants, their local counterparts and social policies.

Overview of Immigration Policies and Exclusions

The dynamics of social exclusion and inclusion of certain groups of citizens

and migrant workers is a complex and multi-dimensional process, which is

shaped by institutional frameworks as well as informal practices through

which peoples lives may be constrained, conned, supported or liberated.

Low-skilled Overseas Migrant Workers

Up until 1990, the South Korean government had been very restrictive

about the admission of blue-collar foreign labour migrants. Since then,

the government has begun to open its door to foreign migrant workers

through various initiatives. Only a limited number of countries have been

324

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

allowed to export labour into the country and a high proportion of foreign

workers have come from Southeast Asia, including countries like Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam.

With the introduction of the Industrial Trainee Program (ITP) in 1993,

Korean rms were allowed to import foreign trainees. Until 2003, when

the law was extended to overseas workers, imported workers would enter

Korea as a trainee, not as a worker, and thus were excluded from the

basic workers rights under the Labour Standards Law and the Social Insurance System. A representative of a migrant welfare-focused NGO condemned the condition of workers under the ITP in this way:

As the name let us know, they are not labourers but trainees. Therefore, they were not covered by the Labour Standard Act in Korea.

The Industrial Trainee System was just like a modern slavery

system. (26 June 2009)

Criticized as a modern slavery system, the ITP did not allow foreign

workers to join or form any labour unions and although their visa status was

trainee, they actually worked in the factory without proper training and

were not allowed to change employment without the permission of their

employers. Studies have documented appalling working conditions, such

as often being laid off without payment, receiving much less than the

minimum wage and working extremely long hours (Kim, 2004; Seol,

2000). At the same time, because the government did not expand the industrial trainee quota despite a sharp increase in the demand for foreign

workers, it led to a rise in the number of undocumented workers in the

country (Rhee et al., 2005). Lim (2010) argues that the government

played a crucial role in institutionalizing and legitimizing a highly discriminatory labour system and helping to criminalize foreign workers.

The current Employment Permit System (EPS), implemented in 2004,

was a strategic move by the government to ultimately replace the problematic ITP with specic aims to legalize foreign migrant workers who had

already been in the illegal market through rehiring benets,2 develop

better tracking records to control illegal immigration as well as to better

protect their labour rights including the universal minimum wage (Rhee

et al., 2005). The government gave many undocumented workers the oppor2 Since 2007, the government has been extending the rehiring benet to not only those working

with an employment permit but also to those with industrial trainee and training employment

visas, although the benet is conned to certain nations.

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

325

tunity to apply for a permit at the time and those who did not qualify were

given a chance to leave the country without paying any nes. This amnesty

boosted the registered foreign population to 73.4% between 2002 and 2003

(Y. Park, 2004).

Under the EPS foreign workers are restricted to employment in only

ve industries: manufacturing, agriculture and stockbreeding, shing, construction and service (including household service). However, the service

and construction industries are limited to only Korean ethnics. Workers

are only allowed to be employed for a maximum of three years (after

which they are subject to deportation and the accumulated duration of

employment cannot exceed a maximum of six years) and accompanying

family is banned. As such, workers remain on a need basis and are

treated as temporary guest workers. The continued intention of the government is to keep low-skilled migrants temporary, which directly implicates migrants social status as the outsider. One informant from a

labour welfare-focused NGO alluded to the continued problem of undocumented workers under the EPS:

Because theres a three-year time limit for migrant workers, illegal

emigration is an inevitable consequence. Even though they are a

little bit more generous for Korean-Chinese who migrated long

time ago, the problem of migrant workers from the Philippines,

Thailand, Vietnam, Mongolia, etc., is very serious. The government fails to protect them in human rights and social security.

(17 July 2009)

Korean-Chinese who enter under the Working Visit scheme are free to

shift workplace and thus have more bargaining power with their employers

and are less likely to be exploited. Our informant called this difference systematic discrimination. Foreign workers from the former USSR and ethnic

Koreans from China are entitled to enter under the less stringent visa. They

are permitted to enter via the Working Visit scheme which allows them to

work in more occupations and they can stay up to ve years. They are not

subject to the same restrictions as the workers under the EPS.

While there are no formal restrictions for low-skilled migrants to gain

permanent residence status (F5 visa), immigration criteria such as income

and years of legal residence make it very difcult for unskilled workers

whose employment is limited to three years to gain a permanent residence

visa. In 2010, the government announced a new F-2-7 visa programme

exclusively for foreign professionals in order to attract global talent and

326

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

support their settlement in Korea (Heit, 2010). According to one Korean

newspaper, the visa carries with it a number of benets, including more

autonomy in employment options, the right to own a business in ones

own name and a shortened path to a permanent residence visa (F5). In comparison to the immigration policy for high-skilled migrant and ethnic

Koreans, low-skilled non-Korean migrants still face much stricter entry

conditions and their status as guests reinforces them as outsiders.

While the number of illegal workers has remained steady since the

implementation of the EPS, there are still many foreign workers employed

illegally in small companies or sweat-shops, the entertainment industry and

more illicit trades such as prostitution. Figures from the Ministry of

Employment and Labour (2010) indicate the ofcial number of foreigners

illegally staying in South Korea in 2008 was 200,489 and they accounted

for 17.3% of the 1.1 million foreigners residing in the country. In 2011,

one out of every four blue-collar migrants under the EPS whose visa has

expired has become illegal and the numbers are expected to rise (S. Park,

2011; The Korean Herald, 2011). As a result of their working status, they

are often exploited by their employers and marginalized by society. To

address such problems the government has been publicizing its intention

to enforce the schemes deportation provision and to use the police force

to catch illegal workers (Y. Park, 2004).

In Taiwan, from 1989, the government began to open its job market to

blue-collar workers and, similar to South Korea, they can only enter as temporary guest workers. The countries that granted export of blue-collar

workers to Taiwan are Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia,

Vietnam and Mongolia.3 The biggest concentrations of foreign workers

are in manufacturing and care work. In terms of gender, currently 61.3%4

of blue-collar migrant workers are female and 38.7% are male5 (Council

of Labour Affairs, 2010).

Unlike foreign professionals who are initially granted working visas for

three years and can apply for an unlimited number of extensions with no

entry quota, blue-collar foreign workers are in general only allowed to

work for a maximum of two years, in limited industries, governed by a

set quota (although employers may apply once for an extension of no

3 Statistics of each source country as at the end of April 2008 are as follows: Indonesia with

123,524 workers was the highest group working in Taiwan, followed by Thailand 86,059

and the Philippines 85,296 (Council of Labour Affairs, 2010).

4 Or 225,017 workers.

5 Or 142,102 workers.

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

327

more than one year upon the expiration of contract6) (Her, 2007). The accumulated duration of employment cannot exceed a maximum of an accumulated nine years. Unlike foreign professional workers who can be hired by

two employers simultaneously and are free to change employers, they are

not allowed to change employers. Furthermore, unlike the hiring of professionals where employers do not need to publicly advertise the position,

it is a requirement for the recruitment of blue-collar workers. Under the

guest worker programme, the government has established policies and

implemented measures that effectively keep blue-collar workers in temporary status, preventing them from gaining permanent residency. Comparing

the differences in policy treatment between high- and low-skilled workers, a

Taipei-based migrant welfare NGO argued that from the policy level, it is

clear discrimination [towards blue-collar workers] is there (18 May 2009).

Her comments coincide with Tseng and Wangs (2011) observation that

restrictive immigration policies targeted at these workers make them particularly vulnerable to exploitation and marginalization.

Foreign low-skilled workers in Taiwan and South Korea are part of an

increasing number of guest workers who are working under dangerous

and difcult conditions. Restrictions on blue-collar migrant workers in

Taiwan are similar to those set in South Korea. As will be discussed, as outsiders, blue-collar migrants in South Korea and Taiwan face similar problems which originate from national policies that keep unskilled workers

temporary and therefore easily disposable.

In Hong Kong, low-skilled foreign labour is largely concentrated in

domestic work and is dominated by Southeast Asians. In 2006, of a total

of 342,198 ethnic minorities living in Hong Kong, 32.9% were Filipinos

and 25.7% were Indonesians, of which 93.8% and 98.3% respectively

were engaged in elementary occupations (Census Statistics Department,

2006). Unlike professional foreign workers who are eligible to apply for

permanent residency after having ordinarily resided in the city for

seven years, foreign domestic workers are not entitled to become permanent

residents. Under the immigration ordinance, the denition of ordinary residency excludes domestic workers and various other occupational categories

even if they have resided in Hong Kong for many years. Recently, as a result

of a landmark case, there has been widespread debate on equal treatment for

foreign workers. In 2011, the Hong Kong High Court ruled that a Filipino

6 In special circumstances, employers may apply for an additional extension of a maximum

length of six months.

328

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

domestic worker who had lived in Hong Kong since 1986 should be

allowed to apply for permanent residency in the city. It was suggested

that the ruling could lead to more than 100,000 other foreign maids

winning rights to residency (Hunt, 2011). In 2012 the government won

an appeal against the ruling. In 2014, the Court of Final Appeal ruled

that the domestic worker was not entitled to permanent residency, ending

the controversial legal battle over the migration rights of foreign domestic

workers.

Mainland China has an abundance of low-skilled labour and as such

does not rely on the import of foreign labour supplies. Rural to urban

migration of low-skilled workers has been the main form of labour

supply. However, as will be discussed, due to the restrictions under the

household registration (hukou), rural migrants are treated as outsiders and

are deprived of their entitlement of basic welfare and government-provided

services.

Low-income Internal Migrants

Outsiderness is not only experienced by foreign international immigrants

but can also be experienced by internal migrants. In most developed

countries, all citizens are free to move within the boundaries of the nation

state and are entitled to equal access to social assistance. This is generally

the case for citizens in South Korea and Taiwan, although there are some

restrictions. For example, in Taiwan the minimum standard living

expense varies slightly in different counties and municipalities, so citizens

need to have resided in the area for a set period of time in order to access

local social assistance. However, exclusionary practice in South Korea

and Taiwan is not as obvious as in Hong Kong and Mainland China.

This section will focus mainly on the restricted rights of internal migrants

from Mainland China to Hong Kong, and those from rural areas to the

cities in Mainland China who have moved residence within their own

country.

In Hong Kong, while there have been many years of intimate links with

Mainland China through cross-border migration, new immigrants entering

the city under the OWP scheme since the 1990s have create much social

tension. Those coming under the OWP comprise mainly unskilled dependent women and children who are often the spouses of certain categories

of Hong Kong residents the once-illegal immigrants granted residence

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

329

during the early 1980s and older low-income working men who are increasingly involved in cross-border marriages. According to the Hong Kong

Census and Statistic Department, marriages by male Hong Kong residents

registered in Hong Kong, which involved Mainland Chinese women,

increased around 23 times from 703 in 1986 to 15,978 in 2007, and there

has also been a gradual increase of Hong Kong women marrying Mainland

Chinese men.

Historically the OWP scheme had required signicant waiting time,

and some spouses and children waited over a decade to be reunited with

their families in Hong Kong. However, the situation has improved recently

where all spouses who have waited for at least ve years are eligible to enter

the city under the OWP scheme (Bacon-Shone, Lam, & Yip, 2008). Moreover, new arrivals often experience difculties in adapting to life in Hong

Kong, particularly in employment and living environment (Home Affairs

Departments, 2008).

The OWP is not the only way Mainland Chinese can gain residence

status in Hong Kong. For those in the privileged groups such as professionals, they can enter by employment through various channels. One

such method is through the Admission Scheme for Mainland Talent and

Professionals which came into effect in 2003. Unlike the OWP scheme,

there is no set quota or restrictions on employment sectors and the

spouse and unmarried dependent children may be admitted with the applicant to stay in Hong Kong (Immigration Department, 2009).

The treatment of Mainland Chinese spouses and dependent children

under the OWP scheme is clearly different from the treatment of spouses

and dependent children of skilled professionals. The differential treatment

between migrants from poor and rich countries is more obvious. Family

reunion for Hong Kong people with spouses and children in economically

developed countries like the USA, UK and Australia is not subject to such

tight control. Migrants from these rich countries can apply for a work permit

and work in Hong Kong as long as they can nd a job there. They do not

need to be professionals, specialists or have special talents. While the governments agreed human rights obligations involve facilitating family

reunication at a rate that Hong Kongs economic and social infrastructure

can absorb without excessive strain, the OWP scheme and policies targeted at new Mainland Chinese immigrants have been justied in terms

of excessive economic and social strain (Bacon-Shone et al., 2008, p. 3).

This in effect has created not only a barrier to social cohesion and

330

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

integration but also a physical barrier preventing Chinese citizens from

family reunion.

In Mainland China, with the reform starting from the late 1970s and

accelerating during the late 1990s, the national and local authorities have

eased restrictions on obtaining urban residence permits, allowing most citizens to move within the country to work and live. While changes have been

made, recent reforms still contain stringent requirements that treat rural

migrants as second-class citizens, restricting their entitlement to basic

welfare and government-provided services, such as public housing (Wu,

2002; Ye, 2009) and medical health care (Hong et al., 2006; Liu, 2002)

enjoyed by urban residents. The hukou system is still a basis of Chinas

ruralurban apartheid, creating a social division between citizens. While

Taiwan also has a household registration system, unlike in Mainland

China, residency can easily be changed with the government authorities

and household registration does not serve as a tool to restrict movements

within the island. The household registration programme in Taiwan is

designed to collate and supply demographic information and register personal status and relations of its citizens.

In 2001, following earlier pilot schemes, the State Council allowed the

transfer of the hukou registration of certain migrants in all small towns and

cities in Mainland China. However, this does not equate with the abolition

of the hukou system or the removal of restrictions on Chinas internal

migration. In reality, it is replaced by locally determined entry conditions

which are geared to attracting the wealthy, the educated or the highly

skilled, which excludes the great majority of rural migrant workers. Moreover, provincial and municipal governments have set different nancial criteria to obtain an urban registration. In Beijing, a selective migration

scheme took effect in 2001. For a set of three urban hukous (self, spouse

and one child) in one of the eight main districts of Beijing, the individual

must be a private entrepreneur and have paid more than 0.8 million yuan

in taxes annually over three years or a total of 3 million yuan in taxes in

three years. The enterprise needs to have continuously hired more than

100 Beijing citizens for three years, or more than 90% of the employees

are Beijing hukou citizens. The alternative is the housing-purchasing

scheme which is based on home ownership of a commercial housing unit

in a designated district purchased at a designated market price. Applicants

must have no criminal record and not be warranted for arrest or investigation by the public security and judicial authority (Beijing Municipal

Public Security Bureau, 2008a). Recently, migrants who are granted a

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

331

national award can apply for a Beijing hukou but there is currently no

ofcial policy on this (Sina, 2009).

While there are special considerations such as for people who live with

spouses, parents or offspring, demobilized soldiers or those who are above

the age of 45 and have been married to a person with Beijing hukou for over

ten years, urban registration is still beyond reach for the majority of rural

migrants (Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau, 2008b). These new

regulations are more of an immigration scheme to attract the high-skilled

workers, while maintaining signicant barriers against the majority of

migrants who are employed in low-income jobs.

Social Security, Labour Protection and Social Exclusion of

Low-skilled Migrants

The marginalized status of migrants is closely linked with patterns of

inequality in terms of labour protection, access to social services and

social participation, exposing the existence of institutional discrimination

and stratication. Table 2 provides a comparison of the provisions of

national social security between different groups of migrants in the four

cities.

Labour Protection for Low-skilled Foreign Migrant Workers

in Seoul and Taipei

At the policy level, with the exception of domestic workers in Taiwan and

South Korea, foreign labourers legally residing in Taiwan and South Korea

have the same protection under the labour laws as the local citizens. In

South Korea, the Minimum Wage Act covers all employees as dened in

the Labour Standards Act, regardless of their employment status or nationality. In 2011, the hourly minimum wage rate was 4,328 WON7 (approximately US$3.73). The standard workweek is regulated at 8 hours per day

and overtime payment is also regulated under the labour laws. According

to the Ministry of Employment and Labour (2010), foreign workers are

also protected by the four major insurances of the National Social Insurance

System that apply to Korean nationals. Contributions to medical and work

7 Exchange rate: US$1 = 1,159 WON approximately in November 2011.

332

Table 2 Main Forms of National Social Security for Migrants in East Asia

Beijing

Hong Kong

New arrivals (less

than seven years

Ruralurban migrants residence)

Medical Insurance

Employment

Unemployment

Insurance

Labour

Work Injury Insurance

Others

Maternity Insurance

Pension

Pension/Old Age

Insurance

Housing Fund

Housing Accumulation

Fund

Main Public

Assistance

Seoul

Blue-collar

migrant workers

Blue-collar migrant

workers (legal)

National Health

Insurance

Programme

National Medical

Insurance

Blue-collar migrant

workers (illegal)

Employment Insurance

Labour Insurance

Mandatory Provident

Fund

Industrial Accident

Compensation

Insurance

National Pension

Industrial Accident

Compensation

Insurance

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

Health

Taipei

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

333

injury insurance are mandatory, pension insurance is reciprocal8 and unemployment insurance is voluntary. In addition, employers of foreign workers

hired under the EPS have to contribute to additional insurance programmes

which provide labour protection to these workers. Illegal foreigner workers

who have no valid working permits are not protected by the labour law and

are excluded from social protection benets because they do not contribute

to the system (Kim, 2004; Seol, 2000). However, since 1993 they have been

covered by the work injury insurance which includes bottom-line protection

of human rights.

In Taiwan, similar to South Korea, the labour contract offers non-discrimination and legitimate protection in minimum wages, working hours

and working conditions for blue-collar workers. The basic wage is stipulated at TW$959 per hour (approximately US$3.12) (Council of Labour

Affairs, 2008). Employers are required to register foreign labourers in

their company for labour insurance and national health insurance (NHI).

The standard workday of 8 hours and overtime is similar to South Korea

and is also regulated under the labour laws.

While the labour and social rights of low-skilled migrant workers are

protected at the policy level, in reality there are many violations. In our

focus groups in Seoul and Taipei, blue-collar migrant workers similarly

expressed that the above-mentioned labour protection policies are only

practised in large companies, and many employers of small companies

still breach the law. One of the main issues presented in both cities was

related to the implementation of policies. Our informant from a migrant

welfare NGO in Taipei explained the difculty of enforcing the policies:

Actually there is always a contract between the employer and the

worker, everyone has to have contract, but its only a procedure.

Employers dont implement their contract. No worker will ght

for one day off to go through the courts, I mean its impossible

for them!

Although theres an article in the Constitution in the Labour

Standard Law saying that people cannot be discriminated by races,

gender, blah blah blah. But nobody takes it seriously. (18 May

2009)

8 According to the reciprocity principle, this is applicable only to those foreign workers from

countries where National Pension mandatorily applies to foreigners.

9 Exchange rate: US$1 = TW$30.35 approximately in November 2011.

334

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

The violation of labour regulations by employers in Taiwan is well

documented (Lan, 2003; Tierney, 2007; Tseng & Wang, 2011). Our informant pointed out that in Taipei, many migrant workers are receiving less

than the minimum wage because labour insurance, national health insurance

and other migrant fees (e.g. broker fees) are deducted from their salary.

The problem of implementation was also noted by migrant workers in

Seoul. A Filipino male migrant worker, for example, explained that even

legal workers may not necessary have an employment contract which protects their lawful labour rights:

Illegal workers are not given a contract to sign when they start

work. But even for legal workers like us, we have contracts, but

we often have to force the company to give it to us. (5 July 2009)

Because of the strict employment condition that does not allow lowskilled workers to change employers in both Taiwan and South Korea,

this effectively means that when employers violate the law, workers have

limited options but to stay with the company if they want to remain

legal. This impact of such a policy on workers welfare was noted by one

Indonesian male migrant worker in Seoul in this way:

The Department of Labour will not allow us to move to another

company because of immigrant policies. They just ignore our complaints. They say You cant move as your company has not broken

any contractual agreement or labour law. But sometimes even

when the company breaks some laws or some agreements,

maybe salary cutting, or making us work overtime, we cannot do

anything about it. We, as foreigners, dont have any power, even

if they discriminate against us at work. We are just seen as a

foreign resident here. We cant do anything much. (5 July 2009)

Often legal workers are turned into illegal workers after entry by changing

employers or overstaying their visa. Because of their illegal status, migrant

workers have little choice but to work and live in poor conditions and are

often exploited by their employers.

Compared to Taiwan, South Korea arguably has a more restrictive

policy on migrant workers which has an impact on the high number of

undocumented migrants. For example, as noted earlier in this paper, in

Taiwan the maximum accumulated duration of employment is nine years

for blue-collar migrant workers whereas in South Korea it is six years. Furthermore, in Taiwan, blue-collar migrants are allowed to provide household

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

335

services whereas in South Korea workers are not allowed to work in domestic service (except for ethnic Koreans). The estimated number of illegal

workers in Korea is 200,489,10 compared with 34,00011 in Taiwan. While

illegal workers in South Korea arguably receive better protection than

workers in Taiwan as they are covered by the industrial accident compensation insurance, the effectiveness of this measure is doubtful because

they could be deported if they request treatment for injury from accidents.

At a community level, our informants in Seoul reported that church-based

groups provide much support (including medial, counselling and social networks) to both legal and illegal workers. This point is supported by the fact

that many websites of such organizations openly offer assistance to both

categories of migrant workers.

However, what is particularly interesting is that some participants in

our Seoul focus groups expressed their preference to be undocumented

workers. During our interviews with both legal and undocumented

migrants, participants expressed the benet of being illegal is that they

could evade employment restrictions forced upon legal blue-collar

migrant workers. In particular, the biggest advantage of an undocumented

migrant is the freedom to change employers:

If you are legal, even if you dont like the job, you cannot change

jobs. But if you are illegal and you dont like the job, you can quit

anytime. Its very difcult when I am engaged to the factory. So

even if the salary is not satisfactory, I cannot quit because of the

contract (Female Indonesian legal migrant worker in Seoul,

aged 1830, 5 July 2009)

Nevertheless, our informants also noted the downside of being illegal; the

main disadvantage is the constant fear of being caught and sent back home.

At the everyday level, foreign workers in both Seoul and Taipei frequently

encountered social discrimination and marginalization in the workplace. Much

media coverage has reported discrimination towards them, particularly exposing differential treatment from local workers. Our informants in both cities

alluded to such experiences. The following are some of their comments:

Everyone has their own jobs, theyre all different but I think our

jobs are a bit tougher than theirs We are the migrant worker,

10 2008 gure from the South Korea Ministry of Labour.

11 2010 gure (Huang, 2010).

336

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

we should be a little more tired than they are, this is for sure. (Male

Vietnamese migrant worker in Taipei, aged 1830, 17 May 2009)

We, foreigners, foreign workers including illegal workers, work in

the 3D industry: Dirty, Difcult and Dangerous. If I can give a suggestion to the Department of Labour: they should standardize

working safety procedures. Especially for foreign workers, they

should put in the contract all the terms about working conditions.

My working condition in my rst company was really dirty and

really dangerous and really hard! (Male Indonesian migrant

worker in Seoul, 5 July 2009)

Although migrant workers often feel that they are not being treated equally

to locals, many have learned to internalize discrimination by believing that

their status as outsiders is subordinate and justies ill-treatment.

Social Security and Public Services of Internal Migrants in

Hong Kong and Beijing

Citizenship rights entail equal social security protection for all citizens.

However, institutional arrangements such as the hukou system in Mainland

China and the OWP for new arrivals in Hong Kong often restrict internal

migrants access to ofcial social welfare on an equal basis to local residents, thus fortifying their status as outsiders. South Korea and Taiwan

do not have such systems that limit the mobility of internal migrants.

Although migrants moving from rural areas to the cities may experience

some discrimination, this happens in daily social practice rather than institutionalized through state policy.

In Hong Kong, the government has created a barrier preventing vulnerable migrants from receiving social security services on an equal basis to

local permanent residents. The Comprehensive Social Security Assistance

(CSSA) scheme, the main form of means-tested social assistance programme in Hong Kong, provides a safety net for those who cannot

support themselves nancially for various reasons, such as old age, disability, illness, unemployment and earnings too low to meet their basic needs.

Prior to 2004, Hong Kong permanent residents and new immigrants shared

the same residence requirements for CSSA. The condition which now only

applies to permanent residents is to have continuously lived in Hong Kong

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

337

for at least one year immediately before the date of application. Beginning

from 2004, as a result of the governments 2003 report of the Task Force on

Population Policy that pointed to the need to ensure a rational basis on

which Hong Kongs social resources are allocated, new immigrants are

not eligible for CSSA until they have resided in Hong Kong for over

seven years, unless under very special circumstances.

The seven-year requirement is also a condition for the allocation of

public rental housing and purchase of Home Ownership Scheme (HOS)

ats. In addition to income and asset limits, at the time of allocation of

public rental housing and at the application of HOS, at least half of the

family members included in the application must have lived in the city

for seven years. In effect, families of new immigrants are in a disadvantaged

position.

While the economic rationality behind the seven-year residence

requirement has been legitimized by the government (Labour and

Welfare Bureau, 2009), without tackling issues faced by new immigrants

such as work, childcare and family violence, these immigrants are left

with little social protection. For example, many victims of domestic violence are women from Mainland China who are married to older Hong

Kong men. Due to prolonged duration of separation between the

husband and wife before they arrive, disparity in age and disillusionment

upon arrival, they often nd it hard to adapt to the new environment and

conicts occur frequently between the couple (Wong & Hu, 2006). If they

have resided there for less than seven years, they are ineligible to apply

for CSSA and public housing. Consequently it is not possible for them

to leave their spouses even when the couples may be facing intense disputes.

In our female new arrivals focus group, a number of informants were

victims of domestic abuse. For example, one woman who left her

husband with her seven-year old daughter after being constantly abused

could only live on her childs CSSA allowance for survival. It was impossible for her to nd any full-time employment as there was no one to take

care of her daughter:

I could not nd a job. My daughter has many holidays. How could

a job offer me so many holidays? It is impossible. I have to accommodate myself for the job, no job would accommodate itself for me

You could not apply for anything with the time limit [residence

requirement] of seven years My life was pathetic. I was

338

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

helpless. (New arrival woman, resided in Hong Kong for four

years, 18 February 2009)

The low-income groups in Hong Kong are more likely to have limited

supportive relationships beyond their families (Lee, Ruan, & Lai, 2005).

Since most new arrival women lack social networks and access to necessary

information, it makes them particularly exposed to violence as they have

no one to turn to for help. The seven-year residence requirement for eligibility to apply for CSSA effectively means new immigrants who are

facing genuine hardship are left outside the safety net.

Government policies directed at new arrivals have contributed to their

social stigma, leading to difculties in social integration. This can be illuminated through discussions with local respondents on new arrivals settlement experiences and their social welfare:

There are more people using CSSA now. Who are they? They are

usually new arrivals The government hasnt thought about this,

why are the new arrivals using the CSSA immediately when they

come to Hong Kong? (Age 46 + , married woman with children,

employed as a security guard, 22 February 2009)

Discrimination and social stigma against new arrivals have a detrimental

impact on feelings of belonging. As a result, these immigrants often have

many difculties in adapting to and integrating into the new environment.

In Beijing, similar to new arrivals in Hong Kong, rural to urban

migrants often face institutional barriers that are not experienced by local

residents. One example is their restricted access to the Minimum Living

Standard Scheme (MLSS). Similar to CSSA in Hong Kong, it is the

major social assistance programme which provides a safety net ensuring

minimum living standards for poor and vulnerable households in urban

areas. The anti-poverty programme initially focused on the chronically

poor, but later extended to the long-term unemployed, which led to a rise

in the number of beneciaries from 2.6 million in 1999 to 20.6 million in

2002. However, even with this extension of coverage, it only reaches at

best a third of the poor in China (Chen & Barrientos, 2006). The provision

of welfare is exclusively to households with urban registration status and

with per capita income below the locally set poverty line, thus non-registered migrants are explicitly excluded from entitlement through MLSS.

At the core of the social security system in China are its social

insurance programmes which include old-age insurance, unemployment

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

339

insurance, medical insurance, work-related injury insurance, maternity

insurance and the housing provident fund. The basic function of these programmes is to decentralize labour risks and safeguard the basic livelihood

security of workers. While contributions to the ve social insurances and

the housing provident fund are mandatory for all workers under labour contracts, including migrant workers, in reality, due to the typically low-skilled,

informal and mobile nature of the migrants employment, many are not

covered by these insurance schemes. A 2005 United Nations Development

Programme report estimates that less than 5% of the migrant workers

receive full or partial pension insurance (Scheineson, 2009). In Beijing,

according to a NGO working for rural migrants we interviewed, less than

half of the migrant population are actually contributing to the ve insurance

schemes.

Recent efforts have been made to improve the legal protection of

migrant workers. In 2007, the National Peoples Congress adopted a new

Labour Contract Law requiring all employment contracts to be put in

writing within one month of employment and that employers must fully

inform the worker about the nature of the job, working conditions and compensation. Furthermore, it seeks to limit abusive practices by eliminating

short-term contracts. However, according a World Health Organization

report, its enforcement has not been very effective (Cui, 2010).

The consequential impact is evident in the area of healthcare. Without

employment-based health insurance coverage, health care access is close to

impossible for migrant workers. Virtually all ruralurban migrant workers

have to pay for their health care at the point of service, as they are not

covered by health insurance. The high cost of health services and the

lack of any health insurance has resulted in under-utilization of health

care services among migrant workers, leading to a series of ineffective

health-seeking behaviours (Hong et al., 2006). In times of illness, our participants engaged in methods such as unsupervised self-treatment or resting

at home without seeking any formal medical care:

I buy myself medicine. I cannot afford the medical service provided by the hospital. (Age 3145 years, married male, selfemployed, 14 March 2009)

Ofcial discrimination against migrants on the basis of their hukou

status exists in education as well. Under the hukou system only people

with permanent hukous can send their children to local state-subsidized

public schools. Since the local government has only been providing

340

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

nancial support according to the number of school children with permanent residence permits, rural migrants children receive no governmental

subsidies, thus obliging many schools to either go on collecting tuition

fees or charge miscellaneous fees (Eastday.com, 2006).

Since 2006, to ensure the right to education for children of migrant

workers, the law was amended with a new provision which stipulates that

when both parents or legal guardians are migrant workers living with

their children in locations other than where the family is registered, the

local governments where they live and work must provide for the childrens

education (Xinhua News Agency, 2006). Nevertheless, in practice, extra

fees for migrants children continue to be collected by schools.

Our respondents acknowledged that additional fees were still being collected by schools and they felt that the main problem is due to the

implementation process:

The government has special requirements to protect migrant

workers, but it is useless. The lower level does not follow the

order of the upper level they collect heavy fees from us. (Age

3145, married male, self-employed, 16 March 2009)

In addition, they criticized the poor quality of education in many

private schools for migrants children and they pointed to the difculty

for their children to enrol in good quality public schools because of their

migrant status. For example, one migrant worker encountered great challenges to enrol her child to a local school:

Our home is close to XY12 Primary School. However, the school

prefers local students to those who come from the rural area. The

school rejected my childs application. He is forced to study at a

school far away from home. It is discrimination! (Age 3145,

married female, self-employed, 6 March 2009)

The restrictions and loopholes of the hukou system have created not

only an institutional divide between rural and urban citizens, but have

also contributed to the social stigma towards internal migrants at the everyday level. While ofcial Chinese press statements portray recent hukou

reforms as eliminating discrimination in the household registration

system, in reality, as Chan and Buckingham (2008, p. 604) rightly

suggest, the hukou directly and indirectly continues to be a major wall

12 Pseudonym is used to maintain condentiality.

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

341

in preventing Chinas rural population from settling in the city and in maintaining the ruralurban apartheid. These regulations have created institutional barriers preventing vulnerable citizens from receiving basic

social services on an equal basis as their urban counterparts.

Discussion and Conclusion

Institutional arrangements that govern low-income migrants in Seoul,

Taipei, Beijing and Hong Kong often construct and reinforce social exclusion. Dimensions of social status, class and ethnicity impact on the

inclusionexclusion dynamic, and patterns of disparity can be observed

in terms of their access to welfare services, labour rights and social

participation.

In Korea and Taiwan, issues related to internal migration are relatively

minor compared with Hong Kong and Mainland China, where internal

migrants are treated as inferior to their local counterparts because of the

differential approach of the government. In Hong Kong, new arrivals

from Mainland China, largely made up of spouses and children of Hong

Kong citizens, face much more entry restrictions when attempting to

reunite with their families than middle class or professional workers from

Mainland China, who can enter via less restrictive immigration policy for

Mainland China talents. Furthermore, the new arrivals do not have the

same access to social welfare as the locals (Chui, 2002; Law & Lee,

2006) and social exclusion continues to be a problem even after gaining

full citizenship because of negative stereotypes. As So (2003, p. 531)

rightly argues, the governments policy of exclusion has sowed the

seeds of discrimination, polarization and conict against mainland

spouses and children in Hong Kong society.

In socialist Mainland China, while the government has created a very

comprehensive social insurance programme for its citizens, at the policy

level there is still a clear divide between rural and urban hukous (Nielsen,

Nyland, Smyth, & Zhang, 2007; Zhu, 2003). Furthermore, as our study

in Beijing reveals, while internal migrants are entitled to the same national

social insurance, in reality, due to the implementation process, rural to urban

migrants often do not receive full benets (Chan & Buckingham, 2008).

Nevertheless, it needs to be noted that in recent years the central government in China has been more active in absorbing migrant workers into

towns and small cities than the previous policy of stringently and rigidly

342

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

segmenting the rural and urban sectors of the pre-reform period. The central

government has tried to create order in rural to urban migration through

inter-governmental co-operative arrangements and has taken a more positive view of inclusive urbanization, resulting in surges in population mobility and expansion of industrial production in the rural areas, thus placing

the ruralurban divide on a new footing (Chan, 1994; Lei, 2001).

However, in practice, not all rural to urban migrants can enjoy equal opportunities of acquiring urban hukou. Those with higher income or with better

social networks enjoy much higher chances, while it is virtually impossible

for low-income casual workers.

In Beijing, issues related to the foreign blue-collar workers are relatively minor as Mainland China does not rely on foreign workers. Unlike

Seoul and Taipei where foreign workers are heavily concentrated in the

manufacturing industries, in Hong Kong they are mainly employed as domestic helpers. In principle, foreign workers in Seoul and Taipei enjoy the

same minimum wage and full protection under labour legislation as the

local workers, while in Hong Kong foreign domestic workers are not

entitled to the statutory minimum wage because of the non-interventionist

attitude of the government. While at the policy level there has been

improvement in the labour conditions of foreign migrant workers, in

reality many migrant workers in all three cities fail to enjoy full benets

compared with the local workers. The exclusionary frameworks, including

practical arrangements and regulations governing change of employer and

maximum years of stay, make these protections ineffective or inoperative

and institutionalize the foreign migrant workers as outsiders. The actions

of the government in these three places has reinforced low-skilled migrants

temporary status. In particular, these exclusionary frameworks have contributed to the problem of illegal/undocumented workers in Korea (Kim,

2004; Seol, 2000).

One inherent factor leading to the development of exclusionary policies

is the under-valuation of migrants contribution in the four East Asian

societies. These four cities have gone through rapid economic growth in

the past two decades. While the contribution of relatively cheap foreign

labour is one of the essential elements of economic success, workers

effort is largely unrecognized. Temporary migration schemes for bluecollar workers and immigration restrictions on internal migrants that

discourage their settlement in the host societies often have the effect of

excluding them from equal rights as well as carving hegemonic notions

that migrant workers and their families impose a burden on the host

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

343

societies. For example, new arrival families in Hong Kong are stigmatized

as greedy and welfare dependent, rural to urban migrant communities in

Beijing are blamed for aggravating hygienic problem in urban areas, and

blue-collar migrant workers in Taiwan and South Korea are accused of

snapping up the jobs of local people. These biased perceptions help to

rationalize the exclusionary policies against low-income migrants.

Another important observation in our research is the differential treatment

of migrants with different social status, reecting social inequality along class

cleavage, urbanrural divisions, and inequalities in global status between rich

and poor countries. In the four societies we studied, the respective governments have placed very stringent restrictions on low-income migrant

workers and migrant families. In general, they do not enjoy the full social

welfare benets of local people in one way or another. However, each of

the four cities has policies to attract investment migrants, professionals and

people with special skills, or at least there are fewer restrictions on working

permits, years of stay, change of employers, right of abode, and even naturalization. Very often, even the relatively less well-off and less skilled workers

from economically well-off developed countries are welcomed. Similarly

observed by a number of scholars, highly skilled workers are given special

consideration under the international policy, while measures to protect and

facilitate the movement of low-skilled workers are virtually non-existent

(Hugo, 2009; Stahl, 2003). Beijing seems to be a little bit different from the

other three cities as it is still under a socialist regime, and foreigners from

Western countries still face some restrictions. However, as we have pointed

out earlier, higher income rural to urban migrants are enjoying more opportunities in transferring their hukous to the city. On the other hand, workers from

Asia, especially low-income Asian countries like the Philippines, Indonesia

and Pakistan have to face exclusionary policies. The high presence of Southeast and East Asians in 3D jobs, where protection is often inadequate, manifests racial discrimination against migrant workers from these regions.

Ironically, they are discriminated against by Asians who have become rich

only in recent decades, like Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea.

This paper has clearly demonstrated that the marginalized status of lowskilled migrants can be connected to patterns of disparity in terms of their

immigration conditions, labour rights and social welfare. All four societies

have policies to prevent migrant workers from obtaining full citizenship,

and thus maintain their outsider status. Even with internal migration

such as in Beijing or Hong Kong, there are great disparities between the

opportunities and social rights of the low-income workers and the higher

344

Journal of Comparative Asian Development

income group. For those who have obtained full citizenship, they still have

to face discrimination in everyday life. Their unequal and inferior access to

social rights compared with local citizens accrues and proliferates by discriminatory and stigmatizing discourses. In particular, it is the lack of multicultural policy and the anti-migrant sentiment that cultivated the

migration policy of these societies. From these experiences, we can see

that while legislation for the protection of migrant workers is crucial in alleviating marginalization, the sincerity in implementing these policies and

promoting a multicultural society is equally important.

To a certain extent, the governments of these four cities tend to put more

emphasis on economic development and productivity than on human rights

and labour welfare. Maintaining a pool of low-paid migrant workers seems

benecial to economic competitiveness. However, government policy planners frequently play down the negative effect of marginalizing migrants and

cultivating an exclusionary ethos in society. Understanding the institutional

frameworks of immigration and social policies allow us to concretely recognize the extent of marginalization of certain migrant groups and dynamics of

inclusion and exclusion of community relations. More importantly, we

should be aware of the accumulation of the detrimental impacts of class

inequality, disadvantaged global status of Asians and ruralurban divisions

on both migrant workers quality of life and cohesion in society as a

whole. Although some of these exclusionary migrant policies may seem

economically rational in the short term, they will create conicts and problems within the city which is costly to remedy in the long run.

References

Abella, M. (2006). Policies and best practices for management of temporary migration. Paper

presented at International Symposium on International Migration and Development, United

Nations Secretariat, Turin, Italy, 2830 June 2006.

Abella, M., Park, Y. B., & Bohning, W. R. (1995). Adjustments to labour shortages and foreign

workers in the Republic of Korea. ILO International Migration Papers No. 1. Geneva:

International Labour Ofce.

Asis, M. M. B., Piper, N., & Raghuram, P. (2010). International migration and development in Asia:

Exploring knowledge frameworks. International Migration, 48(3), 76106.

Athukorala, P. (1992). The use of migrant remittances in development: Lessons from the Asian

experience. Journal of International Development, 4, 511529.

Athukorala, P. (1993). Improving the contribution of migrant remittances to development: The

experiences of Asian labour-exporting countries. International Migration, 31, 103124.

Migration, Social Policy and Social Exclusion in East Asia

345

Bacon-Shone, J., Lam, J. K. C., & Yip, P. S. F. (2008). The past and the future of the One-way

Permit Scheme in the context of a population policy for Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Bauhinia

Foundation Research Centre.

Bao, J. (2004). Marital acts: Gender, sexuality, and identity among the Chinese Thai diaspora.

Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau. (2008a). Internal migration to Beijing and transfer of

hukou through investment (translated). Beijing: Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau.

Retrieved from http://www.bjgaj.gov.cn/web/detail_getZwgkInfo_44768.html (accessed

January 6, 2010) (In Chinese).

Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau. (2008b). Transfer of urban hukou for dependent family

members of aged parents, spouse and elderly children (translated). Beijing: Beijing Municipal

Public Security Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.bjgaj.gov.cn/web/detail_getZwgkInfo_

44593.html (accessed January 12, 2010) (In Chinese).

Benach, J., Muntaner, C., Delclos, C., Menendezl, M., & Ronquillo, C. (2011). Migration and lowskilled workers in destination countries. Policy Forum, 8(6), 13.