Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ethics of Research

Uploaded by

Zahid AnwerOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ethics of Research

Uploaded by

Zahid AnwerCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ethics of Research

In the last few hundred pages, weve o=ered a lot of practical advice, but almost as much preaching about creating social contracts with your readers, projecting an ethos that will encourage

their trust, guarding against biases in collecting and reporting evidence, avoiding plagiarism, and so on. Now we want to share with

you the underlying ethical issues that shape our advice, hoping

that when you close this book, youll give them more thought.

Everything weve said about research re?ects our belief that

it is a profoundly social activity that connects you both to those

who will use your research and to those who might bene>tor

su=erfrom that use. But it also connects you and your readers

to everyone whose research you used and beyond them to everyone whose research they used. To understand our responsibility

to those in that network, now and in the future, we have to move

beyond mere technique to think about the ethics of civil communication.

We start with two broad conceptions of the word ethics: the forging of bonds that create a community and the moral choices we

face when we act in that community. The term ethical comes from

the Greek ethos, meaning either a communitys shared customs or

an individuals character, good or bad. So far, we have focused on

the community-building aspects of research, the bonds we create

with our readers and our sources. But as does any social activity,

273

274 s o m e l a s t c o n s i d e r a t i o n s

research challenges us to de>ne our individual ethical principles

and then to make choices that honor or violate them.

At >rst glance, a purely academic researcher seems on relatively

safe ethical groundwe are less tempted to sacri>ce principle for

gain than, say, a Wall Street analyst evaluating a stock that her

>rm wants her to push on investors, or a scientist paid by a drug

company to prove that a product is safe (regardless of whether

it works). No teacher will pay you to write a report supporting her

views, and you probably wont have occasion to fake results to gain

famelike the American researcher who became famous (and

powerful) for discovering an HIV virus, when he had in fact borrowed it from a laboratory in France.

Even so, you will face such choices from the very beginning of

your project. Some are the obvious Thou shalt nots:

Ethical researchers do not plagiarize or claim credit for the

results of others.

They do not misreport sources, invent data, or fake results.

They do not submit data whose accuracy they dont trust, unless they say so.

They do not conceal objections that they cannot rebut.

They do not caricature or distort opposing views.

They do not destroy data or conceal sources important for

those who follow.

We apply these principles easily enough to obvious cases: the biologist who used india ink to fake genetic marks on his mice,

the Enron accountants and their auditors at Arthur Andersen who

shredded source documents, the government political advisers

who erase e-mails, or the student who submits a paper purchased

on the Internet.

More challenging are those occasions when ethical principles take us beyond any simple moral Do not to what we should

af>rmatively Do. When we think about ethical choices in that way,

The Ethics of Research

275

we move beyond simple con?icts between our own self-interest

and the honest pursuit of truth, or between what we want for ourselves and what is good for or at least not harmful to others. If reporting research is genuinely a collaborative e=ort between readers and writers to >nd the best solution to shared problems, then

the challenge is to >nd ways to create ethical partnerships to make

ethical choices (what we traditionally call character) that can help

build ethical communities.

Such a challenge raises more questions than we can answer

here. Some of those questions have answers that we all agree on;

others are controversial. The three of us answer some of them

di=erently. But one thing we agree on is that research o=ers every

researcher an ethical invitation that, when not just dutifully accepted but embraced, can serve the best interests of both researchers and their readers.

When you create, however brie?y, a community of shared

understanding and interest, you set a standard for your work

higher than any you could set for yourself alone.

When you explain to others why your research should change

their understanding and beliefs, you must examine not only

your own understanding and interests, but your responsibility

to them if you convince them to change theirs.

When you acknowledge your readers alternative views, including their strongest objections and reservations, you move

closer not just to more reliable knowledge, better understanding, and sounder beliefs, but to honoring the dignity and human needs of your readers.

In other words, when you do research and report it as a conversation among equals working toward greater knowledge and better

understanding, the ethical demands you place on yourself should

redound to the bene>t of alleven when we cannot all agree on a

common good. When you decline that conversation, you risk harming yourself and possibly those who depend on your work.

It is this concern for the integrity of the common work of a

276 s o m e l a s t c o n s i d e r a t i o n s

community that underscores why researchers condemn plagiarism so strongly. Plagiarism is theft, but of more than words. By

not acknowledging a source, the plagiarist steals the modest recognition that honest researchers should receive, the respect that a

researcher spends a lifetime struggling to earn. And that weakens

the community as a whole, by reducing the value of research to

those who follow.

That is true in all research communities, including the undergraduate classroom. The student plagiarist steals not only from

his sources, but from his colleagues by making their work seem

lesser by comparison to what was bought or stolen. When such

intellectual thievery becomes common, the community grows

suspicious, then distrustful, then cynicalEveryone does it. Ill fall

behind if I dont. Teachers must then worry as much about not being tricked as about teaching and learning. Whats worse, the plagiarist compromises her own education and so steals from the

larger society that devotes its resources to training her and her

generation to do reliable work later, work that the community will

depend on.

In short, when you report your research ethically, you join a

community in a search for some common good. When you respect

sources, preserve and acknowledge data that run against your results, assert claims only as strongly as warranted, acknowledge

the limits of your certainty, and meet all the other ethical obligations on your report, you move beyond gaining a grade or other

material goodsyou earn the larger bene>t that comes from creating a bond with your readers. You discover that research focused

on the best interests of others is also in your own.

You might also like

- Elements of Critical Thinking: A Fundamental Guide to Effective Decision Making, Deep Analysis, Intelligent Reasoning, and Independent ThinkingFrom EverandElements of Critical Thinking: A Fundamental Guide to Effective Decision Making, Deep Analysis, Intelligent Reasoning, and Independent ThinkingRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Group 4 HR201 Last Case StudyDocument3 pagesGroup 4 HR201 Last Case StudyMatt Tejada100% (2)

- Part I - Rhetoric and Writing in Professional Contexts - Top HatDocument26 pagesPart I - Rhetoric and Writing in Professional Contexts - Top HatYolanda MabalekaNo ratings yet

- Indexing X Ray Diffraction PatternsDocument28 pagesIndexing X Ray Diffraction PatternsLidia Escutia100% (6)

- Chaman Lal Setia Exports Ltd fundamentals remain intactDocument18 pagesChaman Lal Setia Exports Ltd fundamentals remain intactbharat005No ratings yet

- New Installation Procedures - 2Document156 pagesNew Installation Procedures - 2w00kkk100% (2)

- International Convention Center, BanesworDocument18 pagesInternational Convention Center, BanesworSreeniketh ChikuNo ratings yet

- Developing Quality Research Skills: Getting The Most Out of Your Library and Online ResourcesDocument10 pagesDeveloping Quality Research Skills: Getting The Most Out of Your Library and Online ResourcesKristina ZhangNo ratings yet

- Becker Whose Side Are We OnDocument10 pagesBecker Whose Side Are We OnRicardo Jacobsen GloecknerNo ratings yet

- Research Papers Ethics and MoralityDocument4 pagesResearch Papers Ethics and Moralityafnknohvbbcpbs100% (1)

- Term Paper On Social JusticeDocument6 pagesTerm Paper On Social Justicef1gisofykyt3100% (1)

- Research Paper Topics For EthicsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Ethicsfyswvx5b100% (1)

- Exploring The World of Social Research Design PDFDocument14 pagesExploring The World of Social Research Design PDFShare WimbyNo ratings yet

- Controversial Issues To Write A Research Paper OnDocument6 pagesControversial Issues To Write A Research Paper Onfve140vb100% (1)

- Professional Practice For BeggginingDocument6 pagesProfessional Practice For Beggginingmuhammadiqbalarif1No ratings yet

- What is EthicsDocument5 pagesWhat is EthicshananurdinaaaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Code of EthicsDocument6 pagesThesis On Code of Ethicsrikkiwrightarlington100% (2)

- Becker WhoseSideOn 1967Document10 pagesBecker WhoseSideOn 1967Felipe Ulloa PincheiraNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in ThesisDocument5 pagesEthical Issues in Thesisalyssadennischarleston100% (1)

- Whose Side Are We On Howard BeckerDocument10 pagesWhose Side Are We On Howard BeckerMaría Alejandra galvezNo ratings yet

- ETHICS Session 3Document22 pagesETHICS Session 3Nikhil PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesEthical Issues in Literature Reviewc5rzknsg100% (1)

- Research Ethics For Your PhD: An Introduction: PhD Knowledge, #5From EverandResearch Ethics For Your PhD: An Introduction: PhD Knowledge, #5No ratings yet

- Literature Review Attribution TheoryDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Attribution Theoryea2167ra100% (1)

- Literature Review Research EthicsDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Research Ethicsafdtzfutn100% (1)

- Reason:: Its Power and Limitations, Uses and Abuses in Science, the humanities, Ethics and ReligionFrom EverandReason:: Its Power and Limitations, Uses and Abuses in Science, the humanities, Ethics and ReligionNo ratings yet

- Panaguiton, Ana Michaela J. - Philo1 WRW1 Exam 3 (Revised)Document5 pagesPanaguiton, Ana Michaela J. - Philo1 WRW1 Exam 3 (Revised)MPNo ratings yet

- Good Controversial Topics For Research PaperDocument5 pagesGood Controversial Topics For Research Paperafnkedekzbezsb100% (1)

- Ethics in Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesEthics in Literature Reviewafmzrsqklrhbvb100% (1)

- Modern Socio-Technical Perspectives on PrivacyDocument459 pagesModern Socio-Technical Perspectives on PrivacyIgorFilkoNo ratings yet

- Best Controversial Topics Research PaperDocument6 pagesBest Controversial Topics Research Paperwzsatbcnd100% (1)

- Research Paper Ethics TopicsDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Ethics Topicsaflbmfjse100% (1)

- Social Science Dissertation FormatDocument6 pagesSocial Science Dissertation FormatWriteMyPaperIn3HoursCanada100% (1)

- Dissertation SfuDocument8 pagesDissertation SfuWhatAreTheBestPaperWritingServicesNaperville100% (1)

- Sociological Perspective Research Paper TopicsDocument8 pagesSociological Perspective Research Paper Topicslbiscyrif100% (1)

- Ethical Issues in Qualitative ResearchDocument17 pagesEthical Issues in Qualitative Researchniki098No ratings yet

- Computational Approaches to Studying the Co-evolution of Networks and Behavior in Social DilemmasFrom EverandComputational Approaches to Studying the Co-evolution of Networks and Behavior in Social DilemmasNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Media EthicsDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Media Ethicswgaaobsif100% (1)

- Research Papers Ethical TheoriesDocument4 pagesResearch Papers Ethical Theoriesfvf6r3ar100% (1)

- Skepticism: Positive Thinking, Parapsychology, and Critical ThinkingFrom EverandSkepticism: Positive Thinking, Parapsychology, and Critical ThinkingNo ratings yet

- Why Do ResearchDocument14 pagesWhy Do ResearchMINA REENo ratings yet

- Thinking EthicallyDocument14 pagesThinking EthicallyAnonymous qAegy6GNo ratings yet

- What Are Research Ethics?Document8 pagesWhat Are Research Ethics?Raymala RamanNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology Research Papers PDFDocument5 pagesSocial Psychology Research Papers PDFlqinlccnd100% (1)

- Professional Responsibility and Conflict of Interest: Lois EvelethDocument15 pagesProfessional Responsibility and Conflict of Interest: Lois Evelethputri juliantriNo ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument18 pagesAction Researchwajahatroomi100% (1)

- Ethics Thesis TopicsDocument6 pagesEthics Thesis Topicsmichellebojorqueznorwalk100% (2)

- Non Controversial Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesNon Controversial Research Paper Topicskpqirxund100% (1)

- Handouts Professional PracticesDocument11 pagesHandouts Professional Practicesanon_555513071No ratings yet

- Technology and Ethics Privacy in The WorkplaceDocument28 pagesTechnology and Ethics Privacy in The WorkplaceSweelin TanNo ratings yet

- Media Ethics Research Paper TopicsDocument8 pagesMedia Ethics Research Paper Topicsefdrkqkq100% (1)

- English Assignment P8 - Thania - 119Document4 pagesEnglish Assignment P8 - Thania - 119Tania Esa AprinaNo ratings yet

- Perspectives On Ethics in PersuasionDocument27 pagesPerspectives On Ethics in PersuasionJon NorthropNo ratings yet

- Scert - RPE (9.6.23)Document34 pagesScert - RPE (9.6.23)Bhawna GuptaNo ratings yet

- Good Sociological Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesGood Sociological Research Paper Topicslrqylwznd100% (1)

- Ethics and Law Basic ConceptsDocument24 pagesEthics and Law Basic Conceptsfaizan123khanNo ratings yet

- ValuesDocument24 pagesValuesSaurabh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Ethical IssuesDocument4 pagesDissertation Ethical IssuesOrderAPaperOnlineSaltLakeCity100% (1)

- Unit 4 Introduction To Philosophy Mulungushi University-1Document18 pagesUnit 4 Introduction To Philosophy Mulungushi University-1Bwalya FelixNo ratings yet

- Controversial Topics For Research PapersDocument7 pagesControversial Topics For Research Papersafeeotove100% (1)

- Examples of Sociology Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesExamples of Sociology Research Paper Topicsgz3ezhjc100% (1)

- Professional Ethics Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesProfessional Ethics Research Paper Topicsd0f1lowufam3No ratings yet

- CM200 Opertional ManualDocument21 pagesCM200 Opertional ManualZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- B 658 - B 658M - 01 - Qjy1oc0wmqDocument4 pagesB 658 - B 658M - 01 - Qjy1oc0wmqZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Cartridge Brass Sheet, Strip, Plate, Bar, and Disks: Standard Specification ForDocument6 pagesCartridge Brass Sheet, Strip, Plate, Bar, and Disks: Standard Specification ForJoffre ValladaresNo ratings yet

- B 5 - 00 QjuDocument4 pagesB 5 - 00 QjuHafiz_Murni_4791No ratings yet

- B 654 - 92 R99 - Qjy1nc05mli5oqDocument5 pagesB 654 - 92 R99 - Qjy1nc05mli5oqZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- B 657 - 92 R00 - Qjy1nwDocument6 pagesB 657 - 92 R00 - Qjy1nwZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- B 654 - B 654M - 04 - Qjy1nc9cnju0tqDocument5 pagesB 654 - B 654M - 04 - Qjy1nc9cnju0tqZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- B 654 - B 654M - 03 - Qjy1nc9cnju0ts1sruqDocument7 pagesB 654 - B 654M - 03 - Qjy1nc9cnju0ts1sruqZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Cartridge Brass Sheet, Strip, Plate, Bar, and Disks: Standard Specification ForDocument6 pagesCartridge Brass Sheet, Strip, Plate, Bar, and Disks: Standard Specification ForJoffre ValladaresNo ratings yet

- NCGR Vol IDocument28 pagesNCGR Vol IZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Liquid Phase Sintering by R.M. GermanDocument242 pagesLiquid Phase Sintering by R.M. GermanZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- NCGR Recruitment Recommendations VolDocument2 pagesNCGR Recruitment Recommendations VolZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Certificate: - Submitted MyDocument1 pageCertificate: - Submitted MyZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Plasma SprayDocument5 pagesPlasma SprayZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Ensayos de Impacto E23Document28 pagesEnsayos de Impacto E23Juan LeonNo ratings yet

- List of Polymers With TG and TMDocument1 pageList of Polymers With TG and TMZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Summary of ThermodynamicsDocument16 pagesSummary of ThermodynamicsZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- List of Polymers With TG and TMDocument1 pageList of Polymers With TG and TMZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Introduction To PolymersDocument458 pagesIntroduction To PolymersZahid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Benchmarking Guide OracleDocument53 pagesBenchmarking Guide OracleTsion YehualaNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Technologies Learning ActivitiesDocument7 pagesEmpowerment Technologies Learning ActivitiesedzNo ratings yet

- Weka Tutorial 2Document50 pagesWeka Tutorial 2Fikri FarisNo ratings yet

- Marketing ManagementDocument14 pagesMarketing ManagementShaurya RathourNo ratings yet

- E-TON - Vector ST 250Document87 pagesE-TON - Vector ST 250mariusgrosyNo ratings yet

- 9780702072987-Book ChapterDocument2 pages9780702072987-Book ChaptervisiniNo ratings yet

- SDNY - Girl Scouts V Boy Scouts ComplaintDocument50 pagesSDNY - Girl Scouts V Boy Scouts Complaintjan.wolfe5356No ratings yet

- Railway RRB Group D Book PDFDocument368 pagesRailway RRB Group D Book PDFAshish mishraNo ratings yet

- E2 PTAct 9 7 1 DirectionsDocument4 pagesE2 PTAct 9 7 1 DirectionsEmzy SorianoNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 5 HExDocument16 pagesTutorial 5 HExishita.brahmbhattNo ratings yet

- Learning HotMetal Pro 6 - 132Document332 pagesLearning HotMetal Pro 6 - 132Viên Tâm LangNo ratings yet

- Wind EnergyDocument6 pagesWind Energyshadan ameenNo ratings yet

- Econometrics Chapter 1 7 2d AgEc 1Document89 pagesEconometrics Chapter 1 7 2d AgEc 1Neway AlemNo ratings yet

- Gates em Ingles 2010Document76 pagesGates em Ingles 2010felipeintegraNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Information For Database Replay IssuesDocument10 pagesDiagnostic Information For Database Replay IssuesjjuniorlopesNo ratings yet

- Ju Complete Face Recovery GAN Unsupervised Joint Face Rotation and De-Occlusion WACV 2022 PaperDocument11 pagesJu Complete Face Recovery GAN Unsupervised Joint Face Rotation and De-Occlusion WACV 2022 PaperBiponjot KaurNo ratings yet

- 5.0 A Throttle Control H-BridgeDocument26 pages5.0 A Throttle Control H-Bridgerumellemur59No ratings yet

- An Overview of Tensorflow + Deep learning 沒一村Document31 pagesAn Overview of Tensorflow + Deep learning 沒一村Syed AdeelNo ratings yet

- CCS PDFDocument2 pagesCCS PDFАндрей НадточийNo ratings yet

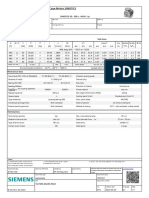

- 1LE1503-2AA43-4AA4 Datasheet enDocument1 page1LE1503-2AA43-4AA4 Datasheet enAndrei LupuNo ratings yet

- Cercado VsDocument1 pageCercado VsAnn MarieNo ratings yet

- Gerhard Budin PublicationsDocument11 pagesGerhard Budin Publicationshnbc010No ratings yet

- Dissolved Oxygen Primary Prod Activity1Document7 pagesDissolved Oxygen Primary Prod Activity1api-235617848No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Style - MakerDocument1 pageEntrepreneurship Style - Makerhemanthreddy33% (3)

- Social EnterpriseDocument9 pagesSocial EnterpriseCarloNo ratings yet

- Database Chapter 11 MCQs and True/FalseDocument2 pagesDatabase Chapter 11 MCQs and True/FalseGauravNo ratings yet