Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism: Fashion or Necessity?: Ancient Asia

Uploaded by

alokOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism: Fashion or Necessity?: Ancient Asia

Uploaded by

alokCopyright:

Available Formats

Ancient Asia

Pratap, A 2014 Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism: Fashion or Necessity?

Ancient Asia, 5: 2, pp.1-4, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/aa.12318

RESEARCH PAPER

Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism: Fashion or

Necessity?

Ajay Pratap*

This paper begins by considering the origins and trajectory of growth of Indian Archaeology, from an

Antiquarian stage, through to its present state, which may best be described, positioned between cultural

historical, Positivist and Post-positivist approaches. The school of archaeological thought informed by

Positivist Philosophy has been called variously as the New Archaeology, Hypothetico-Deductive Archaeology, and more lately as Processual Archaeology (Paddayya, 1990). The school of Indian Archaeology

influenced by the Philosophy of Post-positivism or Postmodernism are called variously as the New New

Archaeology and Postprocessual Archaeology. This paper traces the growth of Indian Archaeology through

its various stages such as Antiquarianism, Indology, Colonial Archaeology, Modern Archaeology, the New

Archaeology and now the Postprocessual Archaeology. It seeks to estimate chiefly the impact of the

Postprocessual applications in Indian Archaeology.

Introduction

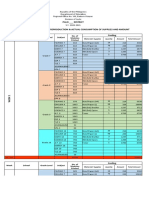

We may tentatively characterize the broad paradigmatic

development of Indian Archaeology (Table 1) in the following way:

Antiquarianism

Speaking of the antiquarian and Indological traditions

of Indian Archaeology, it would be pertinent to mention

the role of the Asiatic Society of Bengal which was established by Sir William Jones at Kolkata in 1784 (Kaul, 1995).

For the better part of the 18th and the 19th centuries, this

Society was very active in research however their publications on Indian archaeology was for that time very piecemeal and thus their notes and news pertaining to Indian

antiquities published during the 18th century maybe

called Antiquarian at best. This is true also because no systematic surveys were undertaken at this time, and hence

both reports of antiquities and their interpretation were

random, piecemeal and subjective. Historical interpretations were very intuitive ones.

Indology

The later work by this Society, however, on Indian History

and Archaeology was more profound and synthetic and

has thus been called Indology. In this phase, mostly for

the better part of the 19th century, Brahmi and Kharoshthi

scripts were deciphered, ancient Indian works of Sanskrit

like the Vedas were translated, and soon an outline of a

nascent Ancient Indian History began to emerge. The discovery of the great ancient Indian ruling dynasties The

* Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

drajayprt@yahoo.com

Nandas, the Mauryas, the Indo-Greeks, the Sunga, the

Kanva, the Kushan up to the Gupta Period, and then again

from Harsha, the Gurjara-Pratihara, the Pala and Sena, the

Rashtrakutas, the Pallavas, Chera, Chola and Pandya of

the pre-Medieval Period of Indian History. The discovery

of Buddhism exercised great influence on ancient Indian

polities through coins and inscriptions. Inscriptions were

found around the country pertaining to a variety of big

and small rulers and dynasties. Excavation of Buddhist

centers of education like Nalanda, Vikramshila or seasonal

residence of monks such as at Ajanta and Ellora, Udayagiri

and Khandagiri, Karle, Bhaja and Kanheri.

Colonial Indian Archaeology

The birth of modern Indian archaeology or Colonial

Archaeology (Ray, 2007) dates perhaps to the first part

of the 20th century, when the finds of Harappa and

Mohenjodaro were made in the 1920s. But the work of

the very first surveyor general Sir Alexander Cunningham,

in the mid-19th century is rightly regarded by many as the

coming of age of Indian or colonial archaeology. Most of

the notable excavations in India (Nalanda, Sarnath and

Bodh Gaya) date to this period as Cunningham was interested to identify the historical places mentioned in Hieun

Tsangs account and his travel in India called the Si-Yu-Ki.

However, the 19th century was also a time when some inkling that India had a prehistory too began to emerge in

the works of those such as Robert Bruce Foote, Valentine

Ball and A.C.L. Carlleyle.

The excavations of Sir John Marshall, M.S. Vats and E.J.H

Mackays at Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Chanhudaro,

which yielded to Indian history a much longer or deeper

a time span than had that of the work of Sir Alexander

Cunningham. Whereas Alexander Cunninghams work

Art.2, page2 of 4

Pratap: Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism

Antiquarianism

18th century

Odds and ends

Indology

18 -19 centuries

Texts and interpretation, study of scripts, epigraphy

and coins, survey of monuments, study of archaeological sites including occasional diggingd

Colonial archaeology

19th and 20th centuries

Systematic survey and excavation

Indian archaeology

20th century mainly after 1947

Survey, excavation and dating

b) Processual or Positivist Phase

1960s to 1980s

Research designs and Hypothesis testing approach

c) Postprocessual, Post-positivist or

Postmodern Phase

1980s onwards to the present and

ongoing

Interpretation, alternate archaeological narratives,

public archaeology, cultural resource management

th

th

Table 1: Development of Indian archaeology.

Sir William Jones and the 19th century

Indological approaches

Sir John Marshall Sir Mortimer Wheeler

Colonial archaeology

H.D. Sankalia, A.H. Dani, B. Subbarao

Cultural, historical and Processual approaches

K. Paddayya, M.L.K. Murty, V.N. Misra, M.K.

New Archaeology: Extending Processual investigations, Precise or Direct

Dhavalikar, S.N. Rajaguru, D.P. Agarwal and others Dating, Ethnoarchaeology, Geoarchaeology, Palaeobotany, Palaeontotolgy,

Theoretical Archaeology, Exploring the merits and the demerits of both

Processual and Postprocessual schools

Table 2: Paradigmatic changes in Indian archaeology.

was concentrated in Central India Sir John Marshall, a

Cambridge trained archaeologist, chose to excavate the

urban history of India such as represented at Harappa and

Mohenjodaro. Not only did John Marshalls work usher

in a new era of modern techniques of excavation and the

recording of excavated data and their analysis, it also laid

down sound principles of archaeological administration

in the form of Archaeological Survey of India (Pratap,

2013). These procedures were then here to stay and to

over-ride not only the methodology of archaeological

studies of the preceding period but also to lay the foundations of a proper system for heritage management than

previously (Thapar, 2009). As enshrined for the first time

in the Ancient Sites and Monuments and Archaeological

Remains Act of 1904, the Indian Archaeological Heritage

Management system sought to lay the foundations of a

single administrative structure governing all the archaeological heritage of India, rather than localized ones as had

been the practice with Cunninghams system.

For colonial archaeology then it was left for Sir Mortimer

Wheeler, the very last of British Director Generals, to

excavate such notable sites as Brahmagiri, Chandravalli,

Arikkamedu, Harappa and to train formally first generation of Indian archaeologists at his famous Taxila School;

where teaching the General Pitt-Rivers Stratigraphic

Method of excavation was the chief purpose. They created

a breed of well-trained Indian archaeologists, on the eve

of decolonization and the birth of an Independent Indian

Archaeology. Amongst the products of the Taxila School

conducted by Sir Mortimer Wheeler was H.D. Sankalia,

one of the fathers of modern Indian Archaeology. In time

he also became the founder of the department of archaeology at the Deccan College in Pune, which remains

to this day one of the best and most comprehensive

departments of archaeology in India. Dr. Sankalias The

Prehistory and Protohistory of India and Pakistan (1978)

is today regarded as one of the earliest and best accounts

of Indian archaeology, which elucidates and summarizes

the pre and protohistory of India on a state-wise basis. As

such it stands as a monument heralding an independent

Indian Archaeology.

Now, if the contributions of the Sir William Jones and

the Asiatic Society of Bengal in the 19th century have been

able to rise above the Antiquarianism of the 18th century

and led to the birth of Indology; if the contributions of

Sir John Marshall and the Archaeological Survey of India

have led to the growth of Colonial Archaeology; then certainly the contribution of Professor H.D. Sankalia and the

Deccan College have facilitated the use of cultural, historical and Processual approaches on large scale.

Thus very briefly we may chart the paradigmatic changes

in Indian archaeology (see Table 2).

Processual Archaeology in India

The New Archaeology or Processual school arose in the

west mainly as a reaction to what was called the culturehistory approach. Workers such as Lewis Binford in the

USA and David Clarke and Colin Renfrew in the UK argued

that archaeology had thus far been seen as a social science

or an art, and was thus seemingly dedicated to picturing dynastic and other sort of cultural histories whereas

it should rather be seen as a science whose aim was to

discover general laws of human behavior. Philosophy of

Science was studied and applied widely to give archaeology and archaeological interpretation a sound positivist

frame of reference and methodology. It was argued that

Pratap: Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism

archaeological interpretation until now was mainly an

intuitive exercise whereas an epistemology that would

give a greater reliability to archaeological inference ought

to be based along scientific lines and therefore that of

the most favoured scientific epistemology or Theory of

Knowledge which is Positivism. Concurrent with such

fundamental changes in archaeology in the west, Indian

archaeologists espoused the New Archaeologys methods wholeheartedly as the logic that archaeology should

aspire to be a science inasmuch as archaeological deductions ought to be testable and verifiable. From the 1970s

full-scale archaeological teaching and research basing

itself upon the New Archaeology approach was initiated

in India. The full thrust of this approach is to be seen

in the works of H.D. Sankalia and his students such as

K. Paddayya, M.K. Dhavalikar, and R.V. Joshi, R.S. Pappu,

Z.D. Ansari and S.N. Raja guru. Their works ranging from

prehistoric surveys and excavations to geomorphological, palaeoclimatic, palaeontological and palaeobotanical investigations, have today given Indian Prehistory a

very firm basis. The works of G.L. Badam, M.D. Kajale, P.K.

Thomas, S.R. Walimbe, P.C. Deotare, Vasant Shinde and P.P.

Joglekar are notable in such a regard.

Postprocessual Archaeology in India

Side by side with such baseline studies of the environment and subsistence types during prehistory,

there developed in the west especially from the 1980s

onwards a penchant or a preoccupation with the Theory

of Archaeology itself. Enshrined mainly in the work

of Ian Hodder who was a student of David Clarke, the

Postprocessual movement took roots 1980s onwards

in Hodders book like The Present Past, Symbolic and

Structural Archaeology and Archaeology as Long-Term

History. Hodder was of the view that the courtship of

archaeology with science was well while it lasted that it

was fundamentally a hopeless enterprise to try to arrive

at General Laws of Human Behaviour. 1980s onwards,

the emphasis in Hodders writing has been that human

cultures are specific in their articulation which results

in very specific material culture production, use and discard, which may vary from culture to culture, or as he

puts it from context to context and hence reconstruction of past behavior cannot be generalized across time

and space. In arguing thus, Hodder was and has been

suggesting the return of archaeology, at least epistemologically, to the folds of the humanities and social

sciences. Since the 1980s, Hodder and his students

like Henrietta Moore (Space, Text and Gender), Daniel

Miller (Artefacts as Categories), Michael Shanks (The

Archaeological Imagination), and Christopher Tilley (The

Archaeology of Landscape), to name just a few, and many

others independently have worked to re-enmesh archaeological theory or archaeological interpretation with and

within social theory (Shanks and Tilleys Social Theory

and Archaeology). Then attention has been drawn to the

Frankfurt School (Jurgen Habermas), Marxist, Structural,

Symbolic and Feminist Theories and more lately to the

study of Agency such as enshrined in the work of Pierre

Art.2, page3 of 4

Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens. The impact of postmodern philosophers like Richard Rorty, Francois Lyotard

and Bruno Latour has added further postmodern social

theory sort of grist to the archaeological mill. Lately,

the Postprocessualist ideas, particularly in the area of

archaeology as material culture, have found resonance

and acceptance within the Cognitive Archaeology School

which has its lineage firmly with the New Archaeology.,

For this paper, Hodders idea of varying archaeological

pasts depending upon context has also led to the rise of

what has been called Indigenous Archaeology in which

archaeological pasts are reckoned as Ethnohistory or

ethnic-group specific pasts.

What has been the impact of all these new developments on Indian Archaeology? It is against such a background, that Indian archaeology has also responded

with some preliminary reflections upon its modernist

or positivist era through such works as Paddayyas The

New Archaeology and Aftermath and D.K. Chakravartis

Theoretical Issues in Indian Archaeology. Others Indian

New Archaeologists have also responded but rather less

judiciously. Chattopadhyaya has argued that postmodernism is a product of late capitalism and commoditizes the

past. However, why then the New Archaeology which also

espoused by and in Capitalist contexts was spared from

this criticism is not clear (1999, 3750).

However, in our reckoning the mandate of a Postprocessual

Indian Archaeology does answer some very urgent and specific needs of the discipline of archaeology beyond rigorous

and reliable interpretation of the past. This is in the realm

of such issues as Ownership and the Management of the

Past, the Past and the Public, and finally whose past is it

that archaeologists are perpetually uncovering and interpreting. This also necessarily includes in the Indian context

issues arising from the use of alternate media for archaeological purposes. There is ample scope in India to attempt

reconstruction of the Indigenous archaeology type and to

analyze material culture patterning within archaeological

cultures as ethnic markers in prehistory.

Therefore, the salient points arising from this discussion

of the impact of Postmodern ideas on Indian archaeology

may be summarized as follows:

a) Under postmodern impact the whole idea of doing

archaeology or being an archaeologist has been

transformed through or due to a variety of reasons.

b) Diverse narratives have to be constructed to make

the past equitable in terms of accessibility to it.

c) Diverse narratives assume that the public who consume archaeological outputs have to be rendered

different accounts of the same archaeological past

in different ways or forms.

d) The idea of archaeological reports and thickly jargoned texts is becoming old fashioned as these

reduce accessibility.

e) Proliferation of archaeological blogs and websites

connected with Indian archaeology themselves indicate the frustration of Indian archaeologists of not

being able to build a one to one relationship with

Art.2, page4 of 4

the reading public fast enough using conventional

means of disseminating the archaeological past.

Conclusion

To conclude, the impact of postmodernism and its

related ideas on Indian archaeology has been that we

have stopped thinking of archaeological material culture

as a passive entity. Further, we have also begun to see

that archaeological evidence hides within itself various

narratives or coded texts pertinent to its space and time

context which informs us greatly about the lifestyles of

contemporary cultures. But more importantly, such narratives may be accessed not only through the methods

of scientific inquiry but also through social theory, as

discussed.

References

Chattopadhyay, U. C. 1999 Models, Metaphors and

Archaeologys Loss of Innocence. In Arora, U.P., Singh,

U.K., Sinha, A.K. (Eds) Currents in Indian History, Art

and Archaeology. Anamika. Delhi.

Kaul, R. K. 1995 Studies in William Jones. An Interpreter of

Oriental Literature. Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

Shimla.

Pratap: Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism

Miller, D. 1985 Artefacts as Categories. A Study of Ceramic

Variability in Central India. New Studies in Archaeology.

Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Paddayya, K. 1990 The New Archaeology and Aftermath.

A View from Outside the Anglo-American World. Ravish

Publishers. Pune.

Pratap, A. 2013 The Geography and archaeology of

shifting cultivation in India: the current scenario. In

Sharma, P.R., Yadava, R.S., Sharma, N. (Eds.) Interdisciplinary Advances in Geography. RK Books. New Delhi.

Ray, H. P. 2007 Colonial Archaeology in South Asia. The

Legacy of Sir Mortimer Wheeler. Oxford University

Press. New Delhi.

Shanks, M. 2012 The Archaeological Imagination. Left

Coast Press.

Shanks, M. and Tilley, C. 1991 Social Theory and Archaeology. Polity Press.

Thapar, B. K. 2009 India. In Cleere, H. (Ed) Approaches to

Archaeological Heritage Management. New Directions

in Archaeology Series. Cambridge University Press.

Cambridge.

Tilley, C. 1997 A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places,

paths and monuments. Explorations in Anthropology.

Bloomsbury Academic.

How to cite this article: Pratap, A 2014 Indian Archaeology and Postmodernism: Fashion or Necessity? Ancient Asia, 5:2, pp.1-4,

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/aa.12318

Published: 21 October 2014

Copyright: 2014 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/.

Ancient Asia is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by Ubiquity Press.

OPEN ACCESS

You might also like

- Unit 2-3Document38 pagesUnit 2-3LyricriseNo ratings yet

- History of Archaeology (English)Document6 pagesHistory of Archaeology (English)Rijan LaskarNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature 2Document45 pagesReview of Literature 2alokNo ratings yet

- American Oriental SocietyDocument3 pagesAmerican Oriental SocietyBalaram PaulNo ratings yet

- Sri Michel Danino: A Noted HistorianDocument3 pagesSri Michel Danino: A Noted HistorianParthasarathi DattaNo ratings yet

- CBCS - 2016-17 Group A (Archaeology) Detailed PDFDocument27 pagesCBCS - 2016-17 Group A (Archaeology) Detailed PDFParvathy KarthaNo ratings yet

- Role of Experiments in The Progress of Science: Lessons From Our HistoryDocument11 pagesRole of Experiments in The Progress of Science: Lessons From Our HistorygaurnityanandaNo ratings yet

- Indian Historical Sources - I: Unit - 1Document5 pagesIndian Historical Sources - I: Unit - 1HuzaifaNo ratings yet

- Recen T Trends in Prehistory of IndiaDocument11 pagesRecen T Trends in Prehistory of Indiaଖପର ପଦା ଜନତାNo ratings yet

- Culture of The Imperial GuptasDocument7 pagesCulture of The Imperial GuptasArwa JuzarNo ratings yet

- Hoi Assignment 1Document17 pagesHoi Assignment 1Sajal S.KumarNo ratings yet

- Science and Technology in India: ModuleDocument15 pagesScience and Technology in India: ModuleAnuj PaliwalNo ratings yet

- Historical Methods in Early India (Shonaleeka Kaul)Document5 pagesHistorical Methods in Early India (Shonaleeka Kaul)Anushka SinghNo ratings yet

- HarappaDocument28 pagesHarappaShubham Trivedi92% (13)

- A Comprehensive Bibliography of The Indus CivilisationDocument37 pagesA Comprehensive Bibliography of The Indus CivilisationMartin ČechuraNo ratings yet

- The Ancient Indus CivilizationDocument11 pagesThe Ancient Indus CivilizationTurfa AhmedNo ratings yet

- Crossing Continents: Between India and the Aegean from Prehistory to Alexander the GreatFrom EverandCrossing Continents: Between India and the Aegean from Prehistory to Alexander the GreatNo ratings yet

- Phases of Indian Art HistoriographyDocument16 pagesPhases of Indian Art HistoriographyJansNo ratings yet

- V R E T C: Edic Oots of Arly Amil UltureDocument16 pagesV R E T C: Edic Oots of Arly Amil UltureRebecca Tavares PuetterNo ratings yet

- HOW ARCHAEOLOGY ILLUMINATED CERTAIN ASPECTS OF INDIAN HISTORY - Zephyr PhillipsDocument7 pagesHOW ARCHAEOLOGY ILLUMINATED CERTAIN ASPECTS OF INDIAN HISTORY - Zephyr PhillipsZephyr PhillipsNo ratings yet

- Module - 4: Scientific Achievements in Ancient IndiaDocument6 pagesModule - 4: Scientific Achievements in Ancient India95shardaNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley Civilization-2257Document5 pagesIndus Valley Civilization-2257RATHLOGICNo ratings yet

- Romila Thapar - Cyclic and Linear Time in Early IndiaDocument13 pagesRomila Thapar - Cyclic and Linear Time in Early IndiaRoberto E. GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Vedic Period Buddha: 1000) Drew Attention To The Overwhelming Mass of Archaeological Evidence ToDocument8 pagesVedic Period Buddha: 1000) Drew Attention To The Overwhelming Mass of Archaeological Evidence ToBlessy AbrahamNo ratings yet

- BsjsjsDocument27 pagesBsjsjsनटराज नचिकेताNo ratings yet

- History: (For Under Graduate Student)Document10 pagesHistory: (For Under Graduate Student)Mrunal NolanNo ratings yet

- The India They SawDocument676 pagesThe India They SawSupratik Sarkar67% (3)

- HistoryOfIndia KamleshKapurDocument2 pagesHistoryOfIndia KamleshKapurkishorepatnaikAINo ratings yet

- M.A. I a.I.H.C. & A. - Credit & Grading SystemDocument29 pagesM.A. I a.I.H.C. & A. - Credit & Grading SystemSachin TiwaryNo ratings yet

- VK JAIN Prehistory and Protohistory ANCEINT INDIADocument228 pagesVK JAIN Prehistory and Protohistory ANCEINT INDIANaina85% (13)

- Cargoes in Motion: Materiality and Connectivity across the Indian OceanFrom EverandCargoes in Motion: Materiality and Connectivity across the Indian OceanNo ratings yet

- Chattopadhyaya, B. D., Early Historical in Indian Archaeology Some Definitional ProblemsDocument12 pagesChattopadhyaya, B. D., Early Historical in Indian Archaeology Some Definitional ProblemsShyanjali DattaNo ratings yet

- Syl PGD ArchDocument27 pagesSyl PGD ArchavaikalamNo ratings yet

- Alexander CunninghamDocument30 pagesAlexander CunninghamAnjnaKandari100% (1)

- Ancient India: A Captivating Guide to Ancient Indian History, Starting from the Beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization Through the Invasion of Alexander the Great to the Mauryan EmpireFrom EverandAncient India: A Captivating Guide to Ancient Indian History, Starting from the Beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization Through the Invasion of Alexander the Great to the Mauryan EmpireNo ratings yet

- The Vinayapitakam and Early Buddhist MonasticismDocument206 pagesThe Vinayapitakam and Early Buddhist Monasticismveghster100% (1)

- (Primary Sources and Asian Pasts) Primary Sources and Asian Pasts - Beyond The Boundaries of The "Gupta Period"Document18 pages(Primary Sources and Asian Pasts) Primary Sources and Asian Pasts - Beyond The Boundaries of The "Gupta Period"Eric BourdonneauNo ratings yet

- Vedic Roots of Early Tamil CultureDocument16 pagesVedic Roots of Early Tamil Cultureimmchr100% (1)

- Ancient Indian History Writing: Early ForeignersDocument5 pagesAncient Indian History Writing: Early Foreignersjitu123456789No ratings yet

- The Development of Archaeology in The Indian: SubcontinentDocument15 pagesThe Development of Archaeology in The Indian: SubcontinentSrikanth GanapavarapuNo ratings yet

- History Research Paper Topics in IndiaDocument12 pagesHistory Research Paper Topics in Indiatug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Buddhist Art of Mathura - TextDocument390 pagesBuddhist Art of Mathura - Textricha sharmaNo ratings yet

- Historic Sources: Literary and ArcheologicalDocument19 pagesHistoric Sources: Literary and ArcheologicalSaloniNo ratings yet

- Component-I (A) - Personal DetailsDocument11 pagesComponent-I (A) - Personal Detailshoney palNo ratings yet

- Research On TamilDocument2 pagesResearch On TamilvijiNo ratings yet

- Unit-1prehistory Protohistory and HistoryDocument13 pagesUnit-1prehistory Protohistory and HistoryLaddan BabuNo ratings yet

- Early Cultural and Historical FormationsDocument8 pagesEarly Cultural and Historical FormationsBarathNo ratings yet

- The Gupta EmpireDocument25 pagesThe Gupta Empireparijat_96427211100% (2)

- Book ReviewDocument22 pagesBook ReviewDisha LohiyaNo ratings yet

- Yantras in Ancient IndiaDocument26 pagesYantras in Ancient Indiakoushik812000No ratings yet

- Syllabus B.A. Aihc WatermarkDocument7 pagesSyllabus B.A. Aihc WatermarkAkash RajNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Understanding Indian Art - Changing PerspectivesDocument20 pagesChapter 3 - Understanding Indian Art - Changing PerspectivesAbhilash Chetia100% (1)

- Early Indian ArchitectureDocument82 pagesEarly Indian Architecturejagannath sahaNo ratings yet

- The Natal Indian Congress, The Mass Democratic Movement and The Struggle To Defeat Apartheid 1980-1994 PDFDocument23 pagesThe Natal Indian Congress, The Mass Democratic Movement and The Struggle To Defeat Apartheid 1980-1994 PDFalokNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - Final Schedule and Abstracts Spalding Symposium 2021Document17 pagesMicrosoft Word - Final Schedule and Abstracts Spalding Symposium 2021alokNo ratings yet

- SBI Apprentice Recruitment 2021 (6100 Vacancies Stipend Rs. 15k - Month) - Apply by July 26 - NoticeBardDocument9 pagesSBI Apprentice Recruitment 2021 (6100 Vacancies Stipend Rs. 15k - Month) - Apply by July 26 - NoticeBardalokNo ratings yet

- Delhi College of Arts and Commerce, Netaji Nagar Wanted Assistant Professor (Guest) - FacultyPlusDocument3 pagesDelhi College of Arts and Commerce, Netaji Nagar Wanted Assistant Professor (Guest) - FacultyPlusalokNo ratings yet

- India (History) ChronologyDocument70 pagesIndia (History) ChronologyAngel Zyesha50% (2)

- Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkars Significant Role in Revival of Buddhism in Modern IndiaDocument28 pagesDr. Babasaheb Ambedkars Significant Role in Revival of Buddhism in Modern IndiaalokNo ratings yet

- Gandhi As A Politician by D. RothermundDocument6 pagesGandhi As A Politician by D. RothermundalokNo ratings yet

- Rccs 6809Document25 pagesRccs 6809Danyal SaleemNo ratings yet

- Dhyana Meditation PDFDocument15 pagesDhyana Meditation PDFalokNo ratings yet

- Microsof) ) T Word - New Formatted Thesis PDFDocument16 pagesMicrosof) ) T Word - New Formatted Thesis PDFalokNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - New Formatted ThesisDocument49 pagesMicrosoft Word - New Formatted ThesisalokNo ratings yet

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar & The Revival of Buddhism in India PDFDocument1 pageDr. B.R. Ambedkar & The Revival of Buddhism in India PDFalokNo ratings yet

- Reconstructing The World - B. R. Ambedkar and Buddhism in India PDFDocument6 pagesReconstructing The World - B. R. Ambedkar and Buddhism in India PDFalok0% (1)

- 04 02 2020 10.29.55 PDFDocument7 pages04 02 2020 10.29.55 PDFalokNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter 3Document13 pages10 Chapter 3mohan kumarNo ratings yet

- The Gaze: Heritage Tourism in Japan and Nepal: A Study of Shikoku and LumbiniDocument29 pagesThe Gaze: Heritage Tourism in Japan and Nepal: A Study of Shikoku and LumbinialokNo ratings yet

- Reserch Methodology Objective Type QuestionsDocument25 pagesReserch Methodology Objective Type QuestionsPankaj Patil100% (2)

- Ten Days Research Methodology Workshop in History 2019Document3 pagesTen Days Research Methodology Workshop in History 2019alokNo ratings yet

- Kurukshetra University KurukshetraDocument1 pageKurukshetra University KurukshetraalokNo ratings yet

- Challenges in Social Entrepreneurship: Dr. N.Rajendhiran and C.SilambarasanDocument3 pagesChallenges in Social Entrepreneurship: Dr. N.Rajendhiran and C.SilambarasanalokNo ratings yet

- Arhat and Bodhisattva Roles and Aspirati PDFDocument12 pagesArhat and Bodhisattva Roles and Aspirati PDFalokNo ratings yet

- The Issue at Hand - Gil FronsdalDocument160 pagesThe Issue at Hand - Gil Fronsdalmelluin100% (1)

- Levels of Human Consciousness According To The Philosophy of GorakhnathDocument5 pagesLevels of Human Consciousness According To The Philosophy of GorakhnathalokNo ratings yet

- Dolma DawaDocument59 pagesDolma DawaalokNo ratings yet

- The Tibetan Diaspora in India and Their Quest For The Autonomy of TibetDocument26 pagesThe Tibetan Diaspora in India and Their Quest For The Autonomy of TibetalokNo ratings yet

- 10 - Part 2 PDFDocument230 pages10 - Part 2 PDFalokNo ratings yet

- Historical Consciousness and Traditional BuddhistDocument16 pagesHistorical Consciousness and Traditional BuddhistalokNo ratings yet

- Dreaming Across The OceansDocument33 pagesDreaming Across The OceansalokNo ratings yet

- Ethnicity and Diasporic Identity (Indian in EU) PDFDocument40 pagesEthnicity and Diasporic Identity (Indian in EU) PDFMichal wojcikNo ratings yet

- Exiled Memory: History, Identity, and Remembering in Southeast Asia and Southeast Asian DiasporaDocument21 pagesExiled Memory: History, Identity, and Remembering in Southeast Asia and Southeast Asian DiasporaalokNo ratings yet

- Delf Lecture 1Document36 pagesDelf Lecture 1Nazia Begum100% (1)

- Parental Involvement Questionare PDFDocument11 pagesParental Involvement Questionare PDFAurell B. SantelicesNo ratings yet

- DLP HGP Quarter 2 Week 1 2Document3 pagesDLP HGP Quarter 2 Week 1 2Arman Fariñas100% (1)

- The Imaginary Life of A Necessary MuseumDocument505 pagesThe Imaginary Life of A Necessary MuseumFilipaNo ratings yet

- Ebonics PDFDocument2 pagesEbonics PDFHaniNo ratings yet

- Pythagoras Theorem LessonDocument5 pagesPythagoras Theorem Lessononek1edNo ratings yet

- Form OJT PDSDocument1 pageForm OJT PDSJiehainie Irag33% (3)

- Functional VocabularyDocument179 pagesFunctional VocabularyEmily Thomas50% (2)

- Transfer Certificate SampleDocument1 pageTransfer Certificate Sampleashutosh SAKNo ratings yet

- Mte K-Scheme Syllabus of Civil EngineeringDocument1 pageMte K-Scheme Syllabus of Civil Engineeringsavkhedkar.luckyNo ratings yet

- Concept and Terms Used in Educational Planning and Administration PDFDocument445 pagesConcept and Terms Used in Educational Planning and Administration PDFArul haribabuNo ratings yet

- Target High Book 5th EditionDocument2 pagesTarget High Book 5th Editionmeera dukareNo ratings yet

- Classroom Continuity Plan SolcpDocument2 pagesClassroom Continuity Plan SolcpGina Dio Nonan100% (1)

- Central University of South Bihar Department of Political StudiesDocument2 pagesCentral University of South Bihar Department of Political StudiesNishant RajNo ratings yet

- St. Anselm's Ontological Argument Succumbs To Russell's ParadoxDocument7 pagesSt. Anselm's Ontological Argument Succumbs To Russell's ParadoxquodagisNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Training and DevelopmentDocument5 pagesCase Study On Training and DevelopmentAakanksha SharanNo ratings yet

- Fix 2Document11 pagesFix 2lutfiyatunNo ratings yet

- Favorite Subject of Grade 10 - ChastityDocument2 pagesFavorite Subject of Grade 10 - ChastitySheery Mariz FernandezNo ratings yet

- Education in Finland ReportDocument17 pagesEducation in Finland ReportJoe BarksNo ratings yet

- AP Music Theory Syllabus 1516Document10 pagesAP Music Theory Syllabus 1516JosephPitoyNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesLesson PlanLynelle MasibayNo ratings yet

- Palo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedDocument5 pagesPalo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedEiddik ErepmasNo ratings yet

- Rules For The Student English Speech CompetitionDocument2 pagesRules For The Student English Speech CompetitionCitaNo ratings yet

- Legends Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLegends Lesson Planapi-489169715100% (2)

- Teaching MethodDocument14 pagesTeaching MethodBiruk EshetuNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Templateapi-318262033No ratings yet

- 2018 International Tuition FeesDocument37 pages2018 International Tuition FeesSafi UllahKhanNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan English ExampleDocument3 pagesLesson Plan English ExampleperakashNo ratings yet

- Trends, Networks and Critical Thinking of The 21 CenturyDocument4 pagesTrends, Networks and Critical Thinking of The 21 CenturyVincent Bumas-ang Acapen100% (1)

- Personal Narrative EssayDocument5 pagesPersonal Narrative EssayBobbi ElaineNo ratings yet