Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Org 5

Uploaded by

Nouman MujahidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Org 5

Uploaded by

Nouman MujahidCopyright:

Available Formats

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

Expert Systems

with Applications

Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

www.elsevier.com/locate/eswa

Knowledge sharing practices as a facilitating factor for improving

organizational performance through human capital: A preliminary test

I-Chieh Hsu

*,1

Dept. of Business Administration, National Changhua University of Education, No. 1, Jin-De Road, Changhua 500, Taiwan

Abstract

Organizational knowledge sharing, argued to be able to improve organizational performance and achieve competitive advantage, is

often not induced successfully. How organizations should encourage and facilitate knowledge sharing to improve organizational performance is still an important research question. This study proposes and examines a model of organizational knowledge sharing that

improves organizational performance. Organizational knowledge sharing practices are argued to be able to encourage and facilitate

knowledge sharing, and are hypothesized to have a positive relationship with organizational human capital (employee competencies),

which is hypothesized to have a positive relationship with organizational performance. Two organizational antecedents (innovation

strategy and top management knowledge values) are hypothesized to lead to the implementation of organizational knowledge sharing

practices. The hypotheses were examined with data collected from 256 companies in Taiwan. All the hypotheses are supported. This

study has both theoretical and practical implications.

2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Knowledge sharing; Performance; Human capital; Innovation strategy; Top management knowledge values

1. Introduction

In the knowledge-based economy, internal resources

and competencies of companies have become a major

focus of management literature (Barney, 1991; Teece,

Pisano, & Shuen, 1997; Wernerfelt, 1984). The analysis of

internal resources has transformed to a focus on intangible

resources; knowledge is seen as a crucial type (Alavi,

Kayworth, & Leidner, 20052006; Davenport et al., 1998;

Drucker, 1993). However, knowledge is not symmetrically

distributed within an organization. Thus, for an organization to develop competitive advantage, identifying, capturing, sharing and accumulating knowledge become crucial

*

Present address: 1600 West Bradley Avenue, Apt. No. C-56, Champaign, IL 61821, US. Tel.: +886 4 7232105x7316; fax: +886 4 7211290.

E-mail addresses: fbhsu@cc.ncue.edu.tw, ichsu@uiuc.edu

1

The present contact is valid only until July 2007.

0957-4174/$ - see front matter 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2007.08.012

(Husted & Michailova, 2002; Michailova & Husted,

2003). An emphasis on knowledge has sparked a recent

interest in performance implications of organizational

knowledge management/sharing processes and practices

(Becerra-Fernandez & Sabherwal, 2001; Hsu, 2006; Lee

& Choi, 2003; Widen-Wul & Soumi, 2007).

However, knowledge sharing is a test of human nature

(Cabrera & Cabrera, 2002; French & Raven, 1959), and

accessing knowledge from colleagues and unknown others

can be dicult (Constant, Sproull, & Kiesler, 1996). As a

result, knowledge sharing within organizations very often

is not successful and organizational performance is not

improved. Managerial interventions are needed to encourage and facilitate systematic knowledge sharing (Hsu,

2006; Husted & Michailova, 2002). Despite the growing

interest in organizational knowledge sharing, empirical

research on performance implications of knowledge sharing practices has not been sucient and is called for (Choi

& Lee, 2003). More importantly, researchers caution that

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

organizational knowledge management/sharing practices

do not directly lead to an improvement of organizational

performance. Rather, organizational performance is

improved through an improvement of intermediate (or

individual) outcomes, following the implementation of

knowledge management/sharing practices (Davenport

et al., 1998; Liebowitz & Chen, 2001; Sabherwal & Bercerra-Fernandez, 2003). A major goal of this research is to

better understand such a causal mechanism.

An organization within which knowledge sharing takes

place will develop its human capital, i.e., competencies of

human resources, through knowledge transfer and

exchange (Quinn, Anderson, & Finkelstein, 1996; WidenWul & Soumi, 2007). As organizational human capital

is developed, human resources can improve their job performance and ultimately, organizational performance with

new and relevant knowledge. This paper seeks to propose

and examine a model of organizational knowledge sharing

in which knowledge sharing practices contribute to organizational performance through the development of human

capital. To this end, the importance of organizational

human capital is rst examined in the literature review section. If the importance of organizational human capital is

established, the importance of organizational knowledge

sharing practices is justied.

Further, although developing human capital is one of

the key objectives of organizational knowledge sharing

practices (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 2002), the relationship

between these practices and human capital has not been

examined. Also, the notion of human capital has been

argued to lie at the core of business success in the 21st century (Hitt, 2000; Liebowitz, 2002). However, the link

between organizational human capital and organizational

performance has been prescriptive and requires empirical

investigation (Lado & Wilson, 1994; Youndt, Subramaniam, & Snell, 2004). Thus, investigating the eect of organizational knowledge sharing practices on organizational

performance through the development of human capital

will not only establish the importance of knowledge sharing practices but also result in ndings that have both theoretical and practical implications.

Finally, for organizational knowledge sharing practices

to eectively develop human capital, inuencing factors

in the organization must be understood (Demarest, 1997;

Malhotra, 2004; ODell & Grayson, 1999). These factors,

or antecedents, serve as infrastructure to improve the eectiveness of organizational knowledge sharing (Holsapple &

Joshi, 2000; Lee & Choi, 2003). This research investigates

the relationships between two important and yet neglected

antecedents (organizational strategy and top management

knowledge values) and knowledge sharing practices. From

a range of literatures, these two antecedents were identied

to underlie and drive knowledge sharing to develop and

exploit knowledge assets (including human capital) for perpetual survival and growth of organizations (Alavi et al.,

20052006; Hamel & Prahalad, 1993, 2005; Ruggles,

1998; Teece & Pisano, 1994; Teece et al., 1997).

1317

2. Literature review

2.1. Organizational human capital

The prevailing denition of organizational human capital adopts a competence perspective (Elias & Scarbrough,

2004). Flamholtz and Lacey (1981) emphasized employee

skills in their theory of human capital. Later researchers

expanded this notion of human capital to include the

knowledge, skills and capabilities of employees that create

performance dierentials for organizations (Nahapiet &

Ghoshal, 1998; Snell & Dean, 1992; Youndt et al., 2004).

Parnes (1984, p. 32) dened human capital as that which

. . . embraces the abilities and know-how of men and

women that have been acquired at some cost and that

can command a price in the labor market because they

are useful in the productive process. Thus, seen from

the competence perspective, the central tenet of human

capital is the purported contributions of human capital to

positive outcomes of organizations. Following this line of

thinking, organizational human capital is dened in this

paper as competencies of employees. Employee competencies can lead to eective job performance (Becerra-Fernandez & Sabherwal, 2001; Davenport et al., 1998). They can

also help in improving nancial performance of organizations (Davenport et al., 1998).

The resource-based view of the rm portends how organizational human capital may help develop a competitive

advantage of an organization. According to this view,

intangible resources or capabilities that are valuable, rare

and dicult to imitate are sources of sustained competitive

advantage of organizations (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991;

Peteraf, 1993; Teece et al., 1997). In particular, a competitive advantage based on a single resource or capability is

easier to imitate than one derived from multiple resources

or capabilities (Barney, 1991; Ulrich & Lake, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984). Organizational human capital constitutes

bundles of unique resources that are valuable, rare, and

inimitable for an organizations competitive advantage.

According to De Saa-Perez and Garca-Falcon (2002),

Lado and Wilson (1994), and Wright, McMahan, and

McWilliams (1994), organizational human capital is valuable because human resources dier in their knowledge,

skills, and capabilities, and they are amenable to value-creation activities guided and coordinated by organizational

strategies and managerial practices. Organizational human

capital is rare because it is dicult to nd human resources

that can always guarantee high performance levels for an

organization. This is due to information asymmetry in

the job market. More importantly, human resources with

various types of knowledge, skills and capabilities are congured in a way that is heterogeneous across organizations.

This makes organizational human capital not just rare but

also inimitable. Finally, the process by which human

resources create performance dierentials requires complex

patterns of coordination and input of other types of

resources. Each depends on the unique context of a given

1318

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

organization. The causal ambiguity and social complexity

inherent in the process have made organizational human

capital non-substitutable and inimitable.

Thus, the above theoretical arguments recognize the

importance of human capital and its development. In addition, in recent years, studies have started to examine the

relationship between organizational human capital and

nancial performance of companies. Findings generally

support that companies with a higher level of human capital tend to have better nancial performance (Youndt,

Snell, Dean, & Lepak, 1996; Youndt et al., 2004). However, as argued by previous literatures, it is worth noting

that a high level of human capital can achieve various other

kinds of positive outcomes, such as innovativeness (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005) and coping capabilities of organizations in fast-changing environments (Wright et al.,

1994). Based on the above discussion,

Hypothesis 1. Organizational human capital is positively

associated with organizational performance.

2.2. Knowledge sharing and organizational knowledge

sharing practices

Organizational knowledge has been commonly dened

as justied true belief (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995, p.

21). It is disseminated within an organization as information of which validity has been established through tests of

proof (Liebeskind, 1996, p. 94). This information can

guide organizational members in their judgments (Tsoukas

& Vladimirou, 2001), and can improve their job performance and ultimately, competitive advantage of organizations (Hsu, 2006).

Knowledge sharing involves the transfer or dissemination of knowledge from one person, or group to another.

Organizational knowledge sharing connects organizational

members with external knowledge sources (Garvin, 1993).

Organizational members benet from networking with

external knowledge sources for new information, expertise,

and ideas that may not be obtained inside the organization

(Hamel & Prahalad, 1993; Wasko & Faraj, 2005). Organizational innovation can be derived from knowledge

exchange and learning from network connections across

organizational boundaries (Nooteboom, 2000). Further,

organizational knowledge sharing helps pass down idiosyncratic, competency-enhancing knowledge from the organization to individuals or from one individual to another.

For example, in a community of practice, collective problem diagnosis and resolution improves interpersonal relationships and knowledge sharing (Wenger & Snyder,

2000). The immediate benet is the enhancement of the

task eectiveness (Sabherwal & Bercerra-Fernandez,

2003) and innovativeness of individuals (Calantone, Cavusgil, & Zhao, 2002). As Quinn et al. (1996, p. 8) put it, As

one shares knowledge with other units, not only do those

units gain information (linear growth); they share it with

others and feed back questions, amplications, and modi-

cations that add further value for the original sender, creating exponential total growth. Thus, organizational

knowledge sharing is an important way to develop organizational human capital.

Organizational knowledge sharing can be the backbone

of organizational learning and bring enormous benets to

an organization (Argote, 1999; Garvin, 1993; Liebowitz

& Chen, 2001). However, employee knowledge sharing

can be dicult because of the costs perceived by the knowledge contributor. Two types of costs are discussed in the

literature (Kankanhalli, Tan, & Wei, 2005). First, tacit

knowledge has to be codied or articulated before it can

be transferred to others (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

Knowledge codication and transfer takes time and

resources. Second, in an organizational context, the knowledge contributor can be seen as forgoing potential rewards

for performing alternative tasks in order to engage in

knowledge sharing. There are opportunity costs associated

with knowledge sharing (Molm, 1997). Thus, employee

knowledge sharing should be facilitated if the costs associated with it can be justied or reduced.

Further, according to social exchange theory, people do

others a favor with a general expectation of some future

return but without a clear expectation of exact future

return (Blau, 1964; Kankanhalli et al., 2005). However, in

addition to the costs associated with knowledge sharing,

knowledge sharing may result in a loss of power or unique

value of the contributor in the organization (French &

Raven, 1959; Szulanski, 1996). Thus, a reward mechanism

should be designed and implemented in an organization in

order to reduce the costs associated with knowledge sharing and avoid the potential loss of value on the part of

the knowledge contributor. More importantly, one should

benet from ones own knowledge sharing behavior. For

example, one may be able to see that ones requests for

knowledge are reciprocally answered by colleagues to

improve ones task performance, after sharing ones knowledge (Connolly & Thorn, 1990; Wasko & Faraj, 2000).

Under such circumstances, employee knowledge sharing

is encouraged.

Organizational knowledge sharing practices facilitate

knowledge sharing because they are initiated and implemented to diuse knowledge and individual learning within

organizations (Calantone et al., 2002). Each individual in

the organization gains from knowledge sharing under the

condition that the organization takes the responsibility of

coding the usable knowledge for its employees (Husted &

Michailova, 2002). In this way, the costs of knowledge

sharing are incurred by the organization. However, not

all knowledge is codiable. Knowledge can be embedded

in action, contextualized in practice and subjected to

actors interpretation (Davenport et al., 1998; Lepak &

Snell, 1999). To achieve best possible gains in knowledge

sharing, social environments can be created within an organization so that individuals can interact with one another

for the sake of knowledge sharing and learning (Currie &

Kerrin, 2003; Liebowitz, 1999; Scarbrough & Carter,

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

2000). Also, an organization can provide incentives to

encourage employee knowledge sharing (Beer & Nohria,

2000; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Hsu, 2006; Liebowitz,

1999). The knowledge contributors future return is met

and knowledge sharing will continue to occur. Employees

do not only benet from the deliberate dissemination of

knowledge to them, but they also benet from employees

sharing knowledge with one another.

Consequently, organizational knowledge sharing practices develop organizational human capital (Liebowitz,

20032004, 2004). Employees knowledge, skills and abilities are enhanced. Calantone et al. (2002) proposed that

an organization should disseminate lessons learned from

past failure to its members. An organization can also use

interdependent arrangements such as work teams, to

enhance the exchange of tacit knowledge and expertise

(Becker, 1964; Lepak & Snell, 1999). Organizational

knowledge sharing practices also include training and

development programs (Becker, 1976; Liebowitz, 1999)

and mentoring programs (Lepak & Snell, 1999), which

equip employees with idiosyncratic knowledge that is more

valuable to the organization than to its competitors. Further, information technology (IT) systems are important

in organizational knowledge sharing (Alavi & Leidner,

2001). Finally, the use of incentive systems should increase

benets as measured by cost-benet equations of social

exchange theory. Employee knowledge sharing will be

encouraged and human capital will be developed.

Hypothesis 2. Organizational knowledge sharing practices

are positively associated with organizational human

capital.

2.3. Organizational strategy

The focal organizational strategy entails dierentiating

one company from its competitors through product innovation (innovation strategy). Organizational knowledge sharing practices are deliberate undertakings of management to

develop organizational human capital as important to

competitive advantage. Consequently, organizational

knowledge sharing practices depend greatly on the strategy

an organization pursues for competitive advantage.

Organizational strategies strongly aect how an organization promotes learning and knowledge sharing, and the

build-up of knowledge assets (including human capital)

within the organization, and ultimately, determines its

competitive advantage (Hamel & Prahalad, 1993, 2005).

Calantone et al. (2002) argued that rms with great innovation capabilities and high innovative performance start

with a shared strategic vision that stresses the importance

of innovation and that guides the creation of innovation

capabilities through organizational knowledge sharing

practices. Grover and Davenport (2001) claimed that a

companys strategy will be enhanced and supported by

an eective use of knowledge. Thus, knowledge management and sharing practices should be integrated with busi-

1319

ness strategy. Knott (2004) further argued that a company

in pursuit of product innovation should direct the implementation of knowledge-updating practices to facilitate

knowledge sharing and creation. Bae and Lawler (2000)

and Bae, Chen, Wan, Lawler, and Walumbwa (2003)

argued that an organizational strategy that aims to dierentiate one company from others through quality and

product or service innovation will support the use of high

performance work systems, which include a variety of practices aimed at information and knowledge sharing.

Therefore,

Hypothesis 3. Organizations that pursue an organizational

strategy characterized by product innovation are more

likely to implement organizational knowledge sharing

practices.

2.4. Top management knowledge values

Values held by top management prescribe how organizational members should conduct themselves, how they

should run the business, and what kind of organization

they should build. Top management values are seen as

the cornerstone of an organizations culture (Alavi et al.,

20052006; Collins & Porras, 1996; Van Maanen & Barley,

1985). Also, top management values underlie organizational culture that drives organizational knowledge sharing

(Alavi et al., 20052006; Ruggles, 1998). Thus, the initiation and implementation of organizational knowledge

sharing practices should start with a top management value

that sees knowledge as a source of competitive advantage

(Bartlett & Ghoshal, 2002; Grover & Davenport, 2001).

Davenport and Prusak (2000) reported that when top managers perceive knowledge as a key strategic resource and

knowledge sharing as the foundation for value creation,

they will support a range of knowledge management practices that aim to facilitate knowledge sharing within organizations. Hsus case study (Hsu, 2006) revealed that

companies that are dedicated to establishing organizational

knowledge sharing practices are observed to have top management support. Such support stems from a top management value that sees knowledge as an important source of

competitive advantage. Thus,

Hypothesis 4. Organizations with upper-level managers

that see knowledge as sources of competitive advantage are

more likely to implement organizational knowledge sharing practices.

3. Research methods

3.1. Procedures and sources of data

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in 2004 with a

sampling frame derived from a senior manager database

provided by The Ministry of Economic Aairs (MOEA),

Taiwan. The MOEA, Taiwan, invites senior managers of

1320

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

business enterprises to participate in an association initiated by the ministry to serve as advisors for other indigenous companies in Taiwan to improve knowledge sharing

between indigenous companies and thereby their competitive advantage. Each company is allowed only one participant in the association. Via this program, the participant

companies obtain access to government advisors, funding

and training programs. Under the promotion of the ministry, the senior manager participants in the association were

aware of the importance of knowledge sharing. Thus, the

MOEA database oers a promising opportunity for this

knowledge sharing study.

Questionnaires were sent to a total of 1486 managers

enlisted as advisors for business enterprises. After followup telephone calls to these managers, 256 usable questionnaires were collected from 256 respective companies, representing a response rate of 17.2%. The 256 respondents

averaged 47.5 years in age and had 23 years of work experience; the male-to-female ratio was approximately 6.41.

They were either top managers (general managers and

chairmen of boards of directors) or functional managers.

The former accounted for 77.7% of the respondents and

the remaining were functional managers. The responding

companies varied in size and industries, and had an average

of 369 employees and 18.7 years of history. Appendix A

reports proles of the responding companies.

3.2. Questionnaire development

Measures of the focal constructs in this paper were

developed from existing literature. Two rounds of questionnaire pretesting were conducted. In the rst round, ve

senior managers with more than 20 years of work experience were provided with the survey. Ambiguities and

sources of confusion in the questionnaire were removed

in light of the comments and suggestions of senior managers. During the second round of pretesting, a revised questionnaire was given to a dierent group of ve managers

with a similar work tenure. Appendix B reports the questionnaire items.

The seven-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1

(totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree) were used throughout the questionnaire. A six-item scale of organizational

human capital was developed by reference to a range of

studies (Delaney & Huselid, 1996; Edvinsson & Malone,

1997; Roos, Roos, Edvinsson, & Dragonetti, 1998; Snell

& Dean, 1992; Youndt et al., 2004). The scale contained

aspects of relative competencies of employees compared

to competitors and the employees use of their competencies to achieve organizational goals. Organizational performance was measured by six items developed from

Khandwalla (1977). The scale reected a range of performance measures and included long-run protability,

growth rate of revenues, employee satisfaction, employee

productivity, goodwill and product (or service) quality.

Organizational knowledge sharing practices are measured by seven items. They included the companys use of

the following practices for knowledge sharing: (1) mentoring programs (Lepak & Snell, 1999), (2) work teams

(Becker, 1964; Lepak & Snell, 1999), (3) training and development programs (Becker, 1976; Liebowitz, 1999), (4) IT

systems (Alavi & Leidner, 2001), (5) knowledge-sharing

mechanisms (Calantone et al., 2002; Liebowitz, 1999),

and (6) incentive systems to encourage knowledge sharing

(Delaney & Huselid, 1996; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000;

Liebowitz, 1999). The seventh item is the company disseminating lessons learned from past failure to its members

(Calantone et al., 2002).

The measurement of top management knowledge values

contained six items. Top management: (1) emphasizes

knowledge sharing within the company, (2) believes that

its support is key to employee knowledge sharing (Davenport et al., 1998; Davenport & Prusak, 2000), (3) sees

through the establishment of knowledge sharing mechanisms (Hsu, 2006), (4) regards knowledge sharing policies

and practices as contributing to company performance,

and (5) protability (Hauschild, Licht, & Stein, 2001;

Husted & Michailova, 2002), and (6) regards rm-specic

knowledge as a source of competitive advantage (Cabrera

& Cabrera, 2002). Finally, a six-item scale for innovation

strategy was developed from Millers (1988) measurement

of innovative dierentiation, i.e., Porters (1980) dierentiation strategy that emphasizes product and service innovation. The scale reected such aspects of organizational

strategy as the speed and performance of new product

(or service) introduction, and cost of new product (or service) development.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model

A conrmatory factor analysis using Amos 4.0 was conducted to test the measurement model. Six model-t measures were used to assess the models overall

appropriateness of t: the ratio of chi-square to degreesof-freedom, goodness of t index (GFI), adjusted goodness

of t index (AGFI), normed t index (NFI), comparative

t index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Following the recommendation of previous literature (Fitzgerald, Drasgow, Hulin, Gelfand, &

Magley, 1997; Robert, Probst, Martocchio, Drasgow, &

Lawler, 2000), three indicators were formed from original

measuring items for each of the latent constructs on the

basis of the items psychometric properties and substantive

content. This procedure maximizes the degree to which the

indicators of each construct share variance. The model

resulting from the conrmatory factor analysis showed

adequate

t

(chi-square/df. = 2.46,

GFI = 0.91,

AGFI = 0.86, NFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.08).

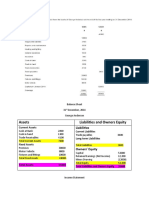

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate Pearson

correlations for the ve construct scales.

Reliability of our construct scales was estimated through

composite reliability (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black,

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

1321

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Construct

Mean

SD

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.09

5.90

5.28

5.27

5.47

0.81

0.80

1.07

0.97

0.88

0.49

0.64

0.51

0.46

0.57

0.55

0.61

0.75

0.65

0.71

Top management knowledge values

Innovation strategy

Organizational knowledge sharing practices

Organizational human capital

Organizational performance

N = 256. Correlations are signicant at 0.001 level.

1998). The composite reliability can be calculated as follows: (the square of the summation of the factor loadings)/{(the square of the summation of the factor

loadings) + (the summation of item measurement error)}.

The composite reliabilities for the ve constructs scales suggested acceptable reliability of the scales for further analysis (top management knowledge values: 0.90, innovation

strategy: 0.85, organizational knowledge sharing practices:

0.91, organizational human capital: 0.92, and organizational performance: 0.89). Convergent validity was evaluated by examining the factor loadings of indicators and

their squared multiple correlations (see Table 2). Following

Hair et al.s (1998) recommendation, factor loadings

greater than 0.50 are considered to be very signicant.

All factor loadings reported in Table 2 are greater than

0.50. Consequently, squared multiple correlations between

these individual indicators and their a priori constructs are

also high. Therefore, all constructs in the measurement

model were judged as having adequate convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was assessed by examining

whether the condence interval around the correlation

Table 2

Factor loadings and squared multiple correlations of remaining items for

all constructs

Construct/indicators

Factor loadings

Squared multiple correlations

Top management knowledge values

Indicator 1

0.86

Indicator 2

0.89

Indicator 3

0.81

0.74

0.79

0.66

Innovation strategy

Indicator 1

Indicator 2

Indicator 3

0.53

0.62

0.60

0.73

0.79

0.78

Organizational knowledge sharing practices

Indicator 1

0.84

0.70

Indicator 2

0.90

0.81

Indicator 3

0.86

0.74

Organizational human capital

Indicator 1

0.93

Indicator 2

0.92

Indicator 3

0.82

0.87

0.85

0.67

Organizational performance

Indicator 1

0.91

Indicator 2

0.92

Indicator 3

0.73

0.82

0.84

0.54

between any two latent constructs includes one (Anderson

& Gerbing, 1988). No condence interval around the correlation in the measurement model included one, which

indicated discriminant validity of the model. A more prudent test of discriminant test requires comparing an unconstrained model that estimates the correlation between a

pair of constructs and a constrained model that xes the

value of the construct correlation to 1 (Chiou, 2004). A signicant dierence in chi-square values between these models (larger than 3.84) was observed. This implied that the

unconstrained model is a better t for the data supporting the existence of discriminant validity.

4.2. Structural model

A similar set of t indices were used to examine the

structural model as shown in Fig. 1. This models t indices

showed good t (Chi-square/df. = 2.75, GFI = 0.90,

AGFI = 0.86, NFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA =

0.08). The structural model helped to examine the predictive power of innovation strategy and top management

team values on organizational knowledge sharing practices,

the predictive power of organizational knowledge sharing

practices on organizational human capital, and the inuence of organizational human capital on organizational

performance.

Hypotheses 3 and 4 investigate the inuences of innovation strategy and top management knowledge values on

organizational knowledge sharing practices. As expected,

innovation strategy (b = 0.42, t-value = 5.66, p < 0.001)

and top management knowledge values (b = 0.46,

t-value = 6.73, p < 0.001) showed strong associations with

organizational knowledge sharing practices. Thus, Hypotheses 3 and 4 were supported. The proposed model

explained 61% of the variance in organizational knowledge

sharing practices.

Hypothesis 2 examines the path from organizational

knowledge sharing practices to organizational human capital. The analysis suggested that organizational knowledge

sharing practices (b = 0.83, t-value = 14.52, p < 0.001)

showed a strong, positive association with organizational

human capital. Hypothesis 2 was supported. The proposed

model accounted for 68% of the variance in organizational

human capital.

Hypothesis 1 examines the path from organizational

human capital to organizational performance. The analysis

1322

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

Top Management

Innovation Strategy

Knowledge Values

0.42 (5.66)** *

0.46 ( 6.73)* **

Organizational

Knowledge Sharing

Practices

R2 = 0.61

0.83 (14.52)***

Organizational

Human Capital

R 2 = 0.68

0.74 (13.56)** *

Organizational

Performance

R2 = 0.55

Notes: ** * p < 0.001; t-values for standardized path coefficients are provided in

parentheses.

Fig. 1. Hypothesis testing results.

suggested that organizational human capital (b = 0.74,

t-value = 13.56, p < 0.001) showed a strong, positive association with organizational performance. Hypothesis 1

was supported. The proposed model accounted for 55%

of the variance in organizational performance.

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. Implications for theory

This study shows the importance of organizational

human capital by providing supporting evidence on its

positive eect on organizational performance. Previously

the importance of organizational human capital was

emphasized, but its eect on organizational performance

has not been thoroughly explored. Instead of using nancial performance as the only measurement of organizational performance, this study uses a wider range of

indicators to measure performance. The data were provided by top or senior managers of the surveyed companies. The study results bring insight into the eects of

organizational human capital. Organizational human capital does not just aect both top-line and bottom-line gures, but also aect a range of performance indicators,

such as quality of products and services and growth potential of companies.

This study also provides a possible mechanism by which

organizational knowledge sharing practices contribute to

organizational performance. Knowledge sharing practices

improve organizational performance through the development of human capital. Activity-based measurement is

developed for organizational knowledge sharing practices.

The practices combine both technical (e.g., IT systems)

and human management systems (e.g., work teams). The

ndings support arguments in the previous literature that

organizational arrangements for employees that support

knowledge sharing will develop organizational human capital (Lepak & Snell, 1999). As human capital helps improve

organizational performance, the importance of organizational knowledge sharing practices cannot be emphasized

too highly.

Innovation strategy is an important predictor of the

implementation of organizational knowledge sharing practices. Organizational knowledge sharing supports a company in its pursuit of innovative outcomes. However, an

overarching strategy should precede knowledge sharing

practices to guide them. In particular, organizational

knowledge sharing practices, under the guide of the strategy, can help companies develop rm-specic human capital that will serve as a basis for competitive advantage. The

eect of organizational strategy on the implementation of

knowledge sharing practices has rarely been examined.

This study contributes to theory building eorts in the eld

of knowledge management research by examining such an

eect.

The values top managers hold toward knowledge are

another important predictor of the implementation of

organizational knowledge sharing practices. Organizational cultural factors have been demonstrated to be associated with organizational knowledge creation processes

(Lee & Choi, 2003). However, values underlie the events,

activities and human relationships (Alavi et al., 2005

2006; Van Maanen & Barley, 1985) that constitute organizational cultures. This study demonstrates the positive relationship between a precursor of organizational culture and

organizational knowledge sharing practices. It demonstrates the importance of leadership in its construction of

a knowledge culture within an organization to facilitate

knowledge sharing and develop human capital.

The overall model examines the enablerpracticeoutcome (Alavi et al., 20052006) or enablerprocessoutcome

(Lee & Choi, 2003) relationship that was proposed to guide

empirical research in the eld. Top management knowledge

values and innovation strategy can be said to be two enablers of organizational knowledge sharing practices. Organizational human capital is an important outcome of the

knowledge sharing practices. The examination of the overall model also serves to provide supporting evidence for

Lado and Wilsons (1994) philosophical claims. They

claimed that strategy, cultural values, and human capital

developing practices should be in place to eectively

develop organizational human capital and promote competitive advantage of an organization. The examination

of the eectiveness of organizational knowledge management/sharing practices had been insucient prior to this

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

study. This study bridges such a gap by supporting the

hypotheses that the organizational knowledge sharing

practices develop organizational human capital, which in

turn improves organizational performance.

5.2. Implications for practices

This study has practical implications. First, the relationships among organizational antecedents, organizational

knowledge sharing practices, organizational human capital

and performance may provide a guide as to how companies

should achieve competitive advantage by using knowledge

sharing practices to develop human capital. Second, companies are advised of the important antecedents that lead

to the success of knowledge sharing practices in developing

human capital. Third, the scale of organizational knowledge sharing practices oers a checklist for companies to

evaluate themselves according to the degree to which they

implement the practices necessary to develop organizational human capital.

6. Conclusions

This study has limitations. First, potential common

method variance may result from the use of self-report

data. Second, the senior manager database used for the survey may be biased. For example, only senior managers with

good company performance are condent enough to be

included in the database. However, Taiwanese business

people share a long tradition of emphasizing guanxi (positive connections) in business operations. Participating in

the association means an extension of a managers social

network and access to government funding and training.

Since the MOEA did not use company performance as a

selection criterion for those applying to join the association, many company senior managers are eager to join

the association. Thus, the selection bias may not be an

important limitation for this study.

Third, the cross-sectional data did not allow a longitudinal investigation of the conceptual framework examined in

this paper. However, this study has opened up a line of

inquiry by examining the causal links between organizational antecedents, organizational knowledge sharing practices, organizational human capital and performance. The

ndings have implications for theory and practice. Future

research is encouraged to follow this line of inquiry to

bring more insight into how organizations should enhance

their performance with well-conceived knowledge sharing

strategies and practices. Such research can broaden the

scope by investigating the relationships between knowledge

management processes, which include acquisition, sharing,

integration, and retention of knowledge, and organizational human capital (Hsu, 2005). Financial performance

measured by objective indicators should also be included

in the investigation.

1323

Appendix A. Proles of responding companies

Characteristics

Frequency Percentage

Industry type

Industry type

(main)

(sub)

Manufacturing Information and

communications

Electronics,

Mechatronics

and

optoelectronics

Metals

Transportation

vehicles and

components

Petrochemicals

and plastics

Food and drinks

Others (textile,

wood, chemicals,

medical and

mechanical

equipments, etc.)

13

5.1

25

9.8

32

12

12.5

4.7

23

9.0

16

26

6.3

10.2

14

5.5

22

8.6

25

9.8

15

32

5.9

12.5

Not reported

Total

1

256

0.4

100

Number of employees

< 100

100 to <500

500 to <1000

1000 to < 5000

>= 5000

Not reported

Total

173

43

17

12

4

7

256

67.6

16.8

6.6

4.7

1.6

2.7

100

Service

Information and

communications

vendors

Management

and nancial

services

Retailing and

wholesaling

Construction

Others (logistics,

transportation,

publication,

technical

services, etc.)

Annual sales (in USD)

<100 000

100 000 to < 500 000

500 000 to <1 million

1 to <100 million

100 to < 500 million

>= 500 million

8

3.1

21

8.2

25

9.8

148

57.8

12

4.7

4

1.6

(Continued on next page)

1324

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

Appendix A (continued)

Characteristics

Frequency Percentage

Not reported

Total

38

256

14.8

100

Capital (in USD)

<100 000

100 000 to < 500 000

500 000 to <1 million

1 to <100 million

100 to < 500 million

>= 500 million

Not reported

Total

20

79

39

86

7

2

23

256

7.8

30.9

15.2

33.6

2.7

0.8

9.0

100

Note: The exchange rate between USD and New Taiwan

Dollars is about 1:34.

Appendix B. Survey items

Top management knowledge values:

1. Top management emphasizes knowledge sharing within

the company.

2. Top management believes that its support is key to

employee knowledge sharing.

3. Top management sees through the establishment of

knowledge sharing mechanisms in the company.

4. Top management regards knowledge sharing policies

and practices as contributing to company performance.

5. Top management regards knowledge sharing policies

and practices as helpful for the company to earn prots.

6. Top management regards rm-specic knowledge as a

source of competitive advantage.

Innovation strategy:

1. The company sees innovation as the key to perpetual

survival.

2. The company keeps launching new products or services.

3. The company is one step ahead of its major competitors

in introducing its products or services to the market.

4. If the company is one step ahead of its major competitors in introducing its products or services to the market, usually these products or services make good

prots.

5. The company pursues its own successful business model.

6. The company has higher R& D expenses as a percentage

of sales than its competitors.

Organizational knowledge sharing practices:

1. The company uses senior personnel to mentor junior

employees.

2. The company groups employees in work teams.

3. The company analyzes its past failure and disseminates

the lessons learned among its employees.

4. The company invests in IT systems that facilitate knowledge sharing.

5. The company develops knowledge sharing mechanisms.

6. The company oers incentives to encourage knowledge

sharing.

7. The company oers a variety of training and development programs.

Organizational human capital

1. The companys employees identify themselves with company values and vision.

2. The companys employees exert their best eorts to

achieve organizational goals and objectives.

3. The companys employees are better than those of competitors at innovation and R&D.

4. The companys employees are better than those of competitors at reducing the companys operating costs.

5. The companys employees are better than those of competitors at responding to customer demands.

6. The companys employees outperform those of

competitors.

Perceived performance:

1. The company has higher long-run protability than its

competitors.

2. The company has higher growth prospect in sales than

its competitors.

3. The companys employees have higher job satisfaction

than those of competitors.

4. The companys employees have higher productivity than

those of competitors.

5. The company has better goodwill than its competitors.

6. The company has better quality products or services

than its competitors.

References

Alavi, M., Kayworth, T. R., & Leidner, D. E. (20052006). An empirical

examination of the inuence of organizational culture on knowledge

management practices. Journal of Management Information Systems,

22(3), 191224.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and

knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research

issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107136.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling

in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411423.

Argote, L. (1999). Organizational learning: creating, retaining, and

transferring, knowledge. Norwell, MA: Kluwer.

Bae, J., Chen, S.-j., Wan, T. W. D., Lawler, J. J., & Walumbwa, F. O.

(2003). Human resource strategy and rm performance in pacic rim

countries. International Journal of Human Resource Management,

14(8), 13081332.

Bae, J., & Lawler, J. J. (2000). Organizational and HRM strategies in

Korea: impact on rm performance in an emerging economy. Academy

of Management Journal, 43(3), 502517.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage.

Journal of Management, 17, 99120.

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (2002). Building competitive advantage

through people. Sloan Management Review, 43(2), 3441.

Becerra-Fernandez, I., & Sabherwal, R. (2001). Organizational knowledge

management: a contingency perspective. Journal of Management

Information System, 18(1), 2355.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital. New York: Columbia University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1976). The economic approach to human behavior.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Beer, M., & Nohria, N. (2000). Cracking the code of change. Harvard

Business Review, 78(3), 133141.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: John

Wiley.

Cabrera, A., & Cabrera, E. F. (2002). Knowledge-sharing dilemmas.

Organization Studies, 23(5), 687710.

Calantone, R. J., Cavusgil, S. T., & Zhao, Y. (2002). Learning orientation,

rm innovation capability, and rm performance. Industrial Marketing

Management, 31, 515524.

Chiou, J.-S. (2004). The antecedents of consumers loyalty to internet

service providers. Information and Management, 41(6), 685695.

Choi, B., & Lee, H. (2003). An empirical investigation of KM styles and

their eect on corporate performance. Information and Management,

40, 403417.

Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (1996). Building your companys vision.

Harvard Business Review(SeptemberOctober), 6577.

Connolly, T., & Thorn, B. K. (1990). Discretionary databases: theory,

data and implications. In J. Fulk & C. Steineld (Eds.), Organizations

and communication technology (pp. 219233). Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Publications.

Constant, D., Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1996). The kindness of strangers:

the usefulness of electronic weak ties for technical advice. Organization

Science, 7(2), 119135.

Currie, G., & Kerrin, M. (2003). Human resource management and

knowledge management: enhancing knowledge sharing in a pharmaceutical company. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(6), 10271045.

Davenport, T. H., De Long, D. W., & Beers, M. C. (1998). Successful

knowledge management projects. Sloan Management Review, 39(2),

4357.

Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (2000). Working knowledge: how

organizations manage what they know. Boston, MA: Harvard

Business School Press.

De Saa-Perez, P., & Garca-Falcon, J. M. (2002). A resource-based view of

human resource management and organizational capabilities development. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1),

123140.

Delaney, J. T., & Huselid, M. A. (1996). The impact of human resource

management practices on perceptions of organizational performance.

Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 949969.

Demarest, M. (1997). Understanding knowledge management. Long

Range Planning, 30(3), 374384.

Drucker, P. (1993). Post-capitalist society. Oxford: ButterworthHeinemann.

Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M. S. (1997). Intellectual capital: realizing your

companys true value by nding its hidden brainpower. New York:

Harper Business.

Elias, J., & Scarbrough, H. (2004). Evaluating human capital: an

exploratory study of management practice. Human Resource Management Journal, 14(4), 2140.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V.

J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in

organizations: a test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 82, 578589.

Flamholtz, E. G., & Lacey, J. M. (1981). Personnel management, human

capital theory, and human resource accounting. Los Angeles, CA:

Institute of Industrial Relations, University of California.

French, J. R. P., Jr., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D.

Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150167). Ann Arbor,

MI: Institute for Social Research.

1325

Garvin, D. A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business

Review, 71(4), 7891.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage:

implications for strategy formulation. California Management

Review(Summer), 114135.

Grover, V., & Davenport, T. H. (2001). General perspectives on

knowledge management: fostering a research agenda. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 18(1), 521.

Gupta, A. J., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge managements social

dimension: lessons from Nucor steel. Sloan Management Review, 42(1),

7180.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998).

Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: PrenticeHall.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1993). Strategy as stretch and leverage.

Harvard Business Review, 71(2), 7584.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (2005). Strategic intent. Harvard Business

Review, 83(7/8), 148161.

Hauschild, S., Licht, T., & Stein, W. (2001). Creating a knowledge culture.

The McKinsey Quarterly, 1(6), 7481.

Hitt, M. A. (2000). The new frontier: transformation of management for

the new millennium. Organizational Dynamics, 28(3), 716.

Holsapple, C. W., & Joshi, K. D. (2000). An investigation of factors that

inuence the management of knowledge in organizations. Journal of

Strategic Information Systems, 9(0), 235261.

Hsu, I-C. (2005). Developing a model of knowledge management from a

human capital perspective preliminary thoughts. Paper Presented at

the 2005 Academy of Management Meeting, Aug. 5-10. Honolulu,

Hawaii, U.S.

Hsu, I.-C. (2006). Enhancing employee tendencies to share knowledge

case studies of nine companies in Taiwan. International Journal of

Information Management, 26(4), 326338.

Husted, K., & Michailova, S. (2002). Diagnosing and ghting knowledgesharing hostility. Organizational Dynamics, 31(1), 6073.

Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C. Y., & Wei, K.-K. (2005). Contributing

knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: an empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 113143.

Khandwalla, P. (1977). The design of organizations. New York: Hartcourt

Brace Jovanovich.

Knott, A. M. (2004). Persistent heterogeneity and sustainable innovation.

Strategic Management Journal, 24(8), 687705.

Lado, A. A., & Wilson, M. C. (1994). Human resource systems and

sustained competitive advantage: a competency-based perspective.

Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 699727.

Lee, H., & Choi, B. (2003). Knowledge management enablers, processes,

and organizational performance: an integrative view and empirical

examination. Journal of Management Information Systems, 20(1),

179228.

Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (1999). The human resource architecture:

toward a theory of human capital allocation and development.

Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 3148.

Liebeskind, J. P. (1996). Knowledge, strategy, and the theory of the rm.

Strategic Management Journal, 17(Winter Special Issue), 93107.

Liebowitz, J. (1999). Key ingredients to the success of an organizations

knowledge management strategy. Knowledge and Process Management,

6(1), 3740.

Liebowitz, J. (2002). Facilitating innovation through knowledge sharing: a

look at the us naval surface warfare center carderock division.

Journal of Computer Information Systems, 42(5), 16.

Liebowitz, J. (20032004). A knowledge management strategy for Jason

organization. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 44(2), 15.

Liebowitz, J. (2004). Bridging the knowledge and skills gap: tapping

federal retirees. Public Personnel Management, 33(4), 421448.

Liebowitz, J., & Chen, Y. (2001). Developing knowledge-sharing prociencies: building a supportive culture for knowledge-sharing. Knowledge Management Review, 3(6), 1215.

Malhotra, Y. (2004). Why knowledge management systems fail: enablers

and constraints of knowledge management in human enterprises. In C.

1326

I.-C. Hsu / Expert Systems with Applications 35 (2008) 13161326

W. Holsapple (Ed.), Handbook on knowledge management 1: knowledge

matters (pp. 577599). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Michailova, S., & Husted, K. (2003). Knowledge sharing hostility in

Russian rms. California Management Review, 45(3), 5977.

Miller, D. (1988). Relating porters business strategies to environments

and structure: analysis and performance implications. Academy of

Management Journal, 31(2), 280308.

Molm, L. D. (1997). Coercive power in social exchange. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and

the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23,

242266.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge creating company. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Nooteboom, B. (2000). Learning by interaction: absorptive capacity,

cognitive distance and governance. Journal of Management and

Governance, 4(12), 6992.

ODell, C., & Grayson, C. J. Jr., (1999). Knowledge transfer: discover

your value propositions. Strategy & Leadership, 27(2), 1015.

Parnes, H. S. (1984). People power. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: a

resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179191.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive advantage: techniques for analyzing

industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

Quinn, J. B., Anderson, P., & Finkelstein, S. (1996). Leveraging intellect.

Academy of Management Executive, 10(3), 726.

Robert, C., Probst, T. M., Martocchio, J. J., Drasgow, F., & Lawler, J. J.

(2000). Empowerment and continuous improvement in the United

States, Mexico, Poland, and India: predicting t on the basis of the

dimensions of power distance and individualism. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 85(5), 643658.

Roos, J., Roos, G., Edvinsson, L., & Dragonetti, N. C. (1998). Intellectual

capital: navigating in the new business landscape. New York: New York

University Press.

Ruggles, R. (1998). The state of notion: knowledge management in

practice. California Management Review, 40(3), 8089.

Sabherwal, R., & Bercerra-Fernandez, I. (2003). An empirical study of the

eect of knowledge management processes at individual, group and

organizational levels. Decision Sciences, 24(2), 225260.

Scarbrough, H., & Carter, C. (2000). Investigating knowledge management.

London: CIPD.

Snell, S. A., & Dean, J. W. Jr., (1992). Integrated manufacturing and

human resource management: a human capital perspective. Academy

of Management Journal, 35(3), 467504.

Subramaniam, M., & Youndt, M. A. (2005). The inuence of intellectual

capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 450463.

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the

transfer of best practice within the rm. Strategic Management

Journal, 17, 2743.

Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1994). The dynamic capabilities of rms: an

introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3, 537556.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities

and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18,

509533.

Tsoukas, H., & Vladimirou, E. (2001). What is organizational knowledge?

Journal of Management Studies, 38(7), 973993.

Ulrich, D., & Lake, D. (1991). Organizational capability: creating

competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 7(1),

7792.

Van Maanen, J., & Barley, S. R. (1985). Cultural organization: fragments

of a theory. In P. J. Frost, L. F. Moore, M. R. Louise, C. C. Lundberg,

& J. Martin (Eds.), Organizational culture (pp. 3154). Beverly Hills:

Sage.

Wasko, M. M., & Faraj, S. (2000). It is what one does: why people

participate and help others in electronic communities of practice.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 9(2/3), 155173.

Wasko, M. M., & Faraj, S. (2005). Why should i share? examining social

capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice.

MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 3557.

Wenger, E. C., & Snyder, W. M. (2000). Communities of practice:

the organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 139

145.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource based view of the rm. Strategic

Management Journal, 5, 171180.

Widen-Wul, G., & Soumi, R. (2007). Utilization of information

resources for business success: the knowledge sharing model. Information Resources Management Journal, 20(1), 4667.

Wright, P. M., McMahan, G. C., & McWilliams, A. (1994). Human

resources and sustained competitive advantage: a resource-based

perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management,

5(2), 301326.

Youndt, M. A., Snell, S. A., Dean, J. W., Jr., & Lepak, D. P. (1996).

Human resource management, manufacturing strategy, and rm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 949969.

Youndt, M. A., Subramaniam, M., & Snell, S. A. (2004). Intellectual

capital proles: an examination of investments and returns. Journal of

Management Studies, 41(2), 335361.

You might also like

- Notes On Inventory ValuationDocument7 pagesNotes On Inventory ValuationNouman Mujahid100% (2)

- Assignment On DepreciationDocument4 pagesAssignment On DepreciationNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Depreciation and Carrying AmountDocument12 pagesDepreciation and Carrying AmountNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Notes On Working Capital ManagementDocument11 pagesNotes On Working Capital ManagementNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Dividends: Factors Affecting Dividend PolicyDocument7 pagesDividends: Factors Affecting Dividend PolicyNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Merger: Acquiring CompanyDocument3 pagesMerger: Acquiring CompanyNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Assets Liabilities and Owners EquityDocument9 pagesAssets Liabilities and Owners EquityNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Accounts Payable ManagementDocument3 pagesAccounts Payable ManagementNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Quiz of DividendDocument1 pageQuiz of DividendNouman Mujahid0% (1)

- Averageinvestment Under Proposed /actual Plan (Total Variable Cost) / (Turnover of Accounts Receivable)Document1 pageAverageinvestment Under Proposed /actual Plan (Total Variable Cost) / (Turnover of Accounts Receivable)Nouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- What Is Behavioral FinanceDocument4 pagesWhat Is Behavioral FinanceNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Breakeven Analysis: EBIT $0Document5 pagesBreakeven Analysis: EBIT $0Nouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Ebit EBIT Q P-FC-VC Q: Find EBIT Price Quantity Sales - Fixed Cost - VC Per Unit Quantity TVCDocument6 pagesEbit EBIT Q P-FC-VC Q: Find EBIT Price Quantity Sales - Fixed Cost - VC Per Unit Quantity TVCNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Bahvioral FinanceDocument14 pagesBahvioral FinanceNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- How To Write Effective Introduction of An ArticleDocument14 pagesHow To Write Effective Introduction of An ArticleNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Madina Medical StoreDocument29 pagesMadina Medical StoreNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Finance Interview Questions: Carey CompassDocument2 pagesFinance Interview Questions: Carey CompassNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Initial Cash FlowDocument3 pagesInitial Cash FlowNouman Mujahid50% (2)

- Gupta Macroeconomic (2013)Document22 pagesGupta Macroeconomic (2013)Nouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Beta Levered and UnleveredDocument3 pagesBeta Levered and UnleveredNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Org 4Document34 pagesOrg 4Nouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Cross - Iyears Companbs BI Dualitman - O Roa ROE SizeDocument8 pagesCross - Iyears Companbs BI Dualitman - O Roa ROE SizeNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Arbitrage Pricing TheoryDocument5 pagesArbitrage Pricing TheoryNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Bundling Human Capital With Organizational Context: The Impact of International Assignment Experience On Multinational Firm Performance and Ceo PayDocument20 pagesBundling Human Capital With Organizational Context: The Impact of International Assignment Experience On Multinational Firm Performance and Ceo PayNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Corporate Performance and Stakeholder Management: Balancing Shareholder and Customer Interests in The U.K. Privatized Water IndustryDocument14 pagesCorporate Performance and Stakeholder Management: Balancing Shareholder and Customer Interests in The U.K. Privatized Water IndustryNouman MujahidNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pronoun and Antecedent AgreementDocument31 pagesPronoun and Antecedent AgreementJC Chavez100% (1)

- PHD Thesis On Development EconomicsDocument6 pagesPHD Thesis On Development Economicsleslylockwoodpasadena100% (2)

- Kristine Jane T. Zipagan Assignment: 1. Parts of InfographicsDocument2 pagesKristine Jane T. Zipagan Assignment: 1. Parts of InfographicsChristyNo ratings yet

- Latest DLL Math 4 WK 8Document2 pagesLatest DLL Math 4 WK 8Sheryl David PanganNo ratings yet

- Practical Research I - Stem 11 EditedDocument22 pagesPractical Research I - Stem 11 EditedRenzo MellizaNo ratings yet

- 01 - Welcome To ML4TDocument15 pages01 - Welcome To ML4Themant kurmiNo ratings yet

- Mass Culture - Mass CommunicationDocument54 pagesMass Culture - Mass Communicationatomyk_kyttenNo ratings yet

- Gayong - Gayong Sur, City of Ilagan, Isabela Senior High SchoolDocument6 pagesGayong - Gayong Sur, City of Ilagan, Isabela Senior High SchoolRS Dulay100% (1)

- Session 1 - Nature of ReadingDocument9 pagesSession 1 - Nature of ReadingAřčhäńgël Käśtïel100% (2)

- Confrontation MeetingDocument5 pagesConfrontation MeetingcalligullaNo ratings yet

- Lester Choi'sDocument1 pageLester Choi'sca5lester12No ratings yet

- Personality TheoriesDocument10 pagesPersonality Theorieskebede desalegnNo ratings yet

- English 1112E: Technical Report Writing: Gefen Bar-On Santor Carmela Coccimiglio Kja IsaacsonDocument69 pagesEnglish 1112E: Technical Report Writing: Gefen Bar-On Santor Carmela Coccimiglio Kja IsaacsonRem HniangNo ratings yet

- Guía de Aprendizaje: English Level 5Document10 pagesGuía de Aprendizaje: English Level 5Christian PardoNo ratings yet

- Action Plan in English ResDocument3 pagesAction Plan in English ResKarmela VeluzNo ratings yet

- Sagot Sa What's More NG Oral ComDocument2 pagesSagot Sa What's More NG Oral ComMhariane MabborangNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 Q2 2022-2023 Budgeted Lesson MAPEH 4 - MGA - 1Document8 pagesGrade 4 Q2 2022-2023 Budgeted Lesson MAPEH 4 - MGA - 1Dian G. MateoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Beowulf Prelude-Ch 2Document2 pagesLesson Plan Beowulf Prelude-Ch 2api-381150267No ratings yet

- Clarifying The Research Question Through Secondary Data and ExplorationDocument33 pagesClarifying The Research Question Through Secondary Data and ExplorationSyed MunawarNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 11 q2 m1Document14 pagesPractical Research 1 11 q2 m1Kaye Flores100% (1)

- DLL For CotDocument3 pagesDLL For CotLeizel Jane Lj100% (2)

- Behavioural Event InterviewDocument12 pagesBehavioural Event Interviewwgcdrvenky100% (1)

- Q1 - Performance Task No. 1Document1 pageQ1 - Performance Task No. 1keanguidesNo ratings yet

- Employability SkillsDocument19 pagesEmployability SkillsRonaldo HertezNo ratings yet

- 2nd Lesson 1 Types of Speeches and Speech StyleDocument23 pages2nd Lesson 1 Types of Speeches and Speech Styletzuyu lomlNo ratings yet

- Silabus: Jurusan Pendidikan Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesSilabus: Jurusan Pendidikan Bahasa InggrisRusdin SurflakeyNo ratings yet

- Universiti Teknologi Mara Final Examination: Course Organizational Behaviour SMG501 JUNE 2018 3 HoursDocument3 pagesUniversiti Teknologi Mara Final Examination: Course Organizational Behaviour SMG501 JUNE 2018 3 HoursMohd AlzairuddinNo ratings yet

- PSYCH 101 Motivation, Values and Purpose AssignDocument4 pagesPSYCH 101 Motivation, Values and Purpose AssignLINDA HAVENSNo ratings yet

- Answers Handout 3Document2 pagesAnswers Handout 3Дианка МотыкаNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking Toolkit PDFDocument32 pagesDesign Thinking Toolkit PDFDaniela DumulescuNo ratings yet