Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Edward v. Southcarolina

Uploaded by

Thalia SandersOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Edward v. Southcarolina

Uploaded by

Thalia SandersCopyright:

Available Formats

83 S.Ct.

680 Page 1

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

peacefully on sidewalk on State House grounds

constituted a breach of peace under state law, Su-

Supreme Court of the United States preme Court nevertheless had duty to make an inde-

James EDWARDS, Jr., et al., Petitioners, pendent examination of the whole record.

v.

SOUTH CAROLINA. [2] Disorderly Conduct 129 111

No. 86.

129 Disorderly Conduct

Argued Dec. 13, 1962. 129k111 k. Parades, Demonstrations, and Pick-

Decided Feb. 25, 1963. eting in General. Most Cited Cases

(Formerly 62k1(7) Breach of the Peace,

Prosecution of group of Negroes for breach of the 92k274.1(5))

peace. From an adverse judgment of the General

Sessions Court of Richland County, South Carolina, Constitutional Law 92 1431

the defendants appealed. The Supreme Court of

South Carolina, 239 S.C. 339, 123 S.E.2d 247, af- 92 Constitutional Law

firmed, and certiorari was granted. The United 92XIV Right of Assembly

States Supreme Court, Mr. Justice Stewart, held 92k1431 k. Government Property. Most

that arrest, conviction and punishment of group of Cited Cases

Negroes for breach of the peace by marching peace- (Formerly 92k274.1(5))

fully on sidewalk around State House grounds to

Constitutional Law 92 1435

publicize their dissatisfaction with discriminatory

actions against Negroes infringed their constitution- 92 Constitutional Law

ally protected rights of free speech, free assembly, 92XV Right to Petition for Redress of Griev-

and freedom to petition for redress of their griev- ances

ances. 92k1435 k. In General. Most Cited Cases

(Formerly 92k274.1(5))

Reversed.

Constitutional Law 92 1813

Mr. Justice Clark dissented.

92 Constitutional Law

West Headnotes

92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

[1] Criminal Law 110 1134.60 Press

92XVIII(H) Law Enforcement; Criminal

110 Criminal Law Conduct

110XXIV Review 92k1813 k. Breach of the Peace; Unlawful

110XXIV(L) Scope of Review in General Assembly. Most Cited Cases

110XXIV(L)5 Theory and Grounds of (Formerly 92k274.1(5))

Decision in Lower Court Arrest, conviction, and punishment of group of

110k1134.60 k. In General. Most Cited Negroes for breach of the peace by marching peace-

Cases fully on sidewalk around State House grounds to

(Formerly 110k1134(6)) publicize their dissatisfaction with discriminatory

Even accepting as binding decision of state court actions against Negroes infringed their constitution-

that conduct of group of Negroes in marching ally protected rights of free speech, free assembly,

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 2

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

and freedom to petition for redress of their griev- Daniel R. McLeod, Columbia, S.C., for respondent.

ances. U.S.C.A.Const. Amends. 1, 14.

[3] Constitutional Law 92 3851 Mr. Justice STEWART delivered the opinion of the

Court.

92 Constitutional Law

92XXVII Due Process The petitioners, 187 in number, were convicted in a

92XXVII(A) In General magistrate's court in Columbia, South Carolina, of

92k3848 Relationship to Other Constitu- the *230 commonlaw crime of breach of the peace.

tional Provisions; Incorporation Their convictions were ultimately affirmed by the

92k3851 k. First Amendment. Most South Carolina Supreme Court, 239 S.C. 339, 123

Cited Cases S.E. id 247. We granted certiorari, 369 U.S. 870, 82

(Formerly 92k274.1(1), 92k274(1), 92k2) S.Ct. 1141, 8 L.Ed.2d 274, to consider the claim

The freedoms given by the First Amendment are that these convictions cannot be squared with the

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment from inva- Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Consti-

sion by the states. U.S.C.A.Const. Amends. 1, 14. tution.

[4] Constitutional Law 92 1800 There was no substantial conflict in the trial evid-

FN1

ence. Late in the morning of March 2, 1961,

92 Constitutional Law the petitioners, high school and college students of

92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and the Negro race, met at the Zion Baptist Church in

Press Columbia. From there, at **681 about noon, they

92XVIII(H) Law Enforcement; Criminal walked in separate groups of about 15 to the South

Conduct Carolina State House grounds, an area of two city

92k1800 k. In General. Most Cited Cases blocks open to the general public. Their purpose

(Formerly 92k274.1(1)) was ‘to submit a protest to the citizens of South

A state cannot make criminal the peaceful expres- Carolina, along with the Legislative Bodies of

sion of unpopular views. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. South Carolina, our feelings and our dissatisfaction

14. with the present condition of discriminatory actions

against Negroes, in general, and to let them know

[5] Constitutional Law 92 4034 that we were dissatisfied and that we would like for

the laws which prohibited Negro privileges in this

92 Constitutional Law

State to be removed.’

92XXVII Due Process

92XXVII(G) Particular Issues and Applica- FN1. The petitioners were tried in groups,

tions at four separate trials. It was stipulated that

92XXVII(G)1 In General the appeals be treated as one case.

92k4034 k. Speech, Press, Assembly,

and Petition. Most Cited Cases Already on the State House grounds when the peti-

(Formerly 92k274.1(1)) tioners arrived were 30 or more law enforcement

A statute which upon its face, and as authoritatively officers, who had advance knowledge that the peti-

FN2

construed, is so vague and indefinite as to permit tioners were coming. Each group of petitioners

punishment of political discussion is repugnant to entered the grounds through a driveway and park-

guaranty of liberty contained in the Fourteenth ing area known in the record as the ‘horseshoe.’ As

Amendment. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14. they entered, they were told by the law enforcement

**680 *229 Jack Greenberg, for petitioner. officials that ‘they had a right, as a citizen, to go

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 3

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

through the State House grounds, as any other cit- ‘Q. Were the Negro college students or

izen has, as long as they were peaceful.’ During other students well demeaned? Were they

*231 the next half hour or 45 minutes, the petition- well dressed and were they orderly?

ers, in the same small groups, walked single file or

FN3 ‘A. Yes, they were.’

two abreast in an orderly way through the

grounds, each group carrying placards bearing such

During this time a crowd of some 200 to 300 on-

messages as ‘I am proud to be a Negro’ and ‘Down

lookers had collected in the horseshoe area and on

with segregation.’

the adjacent sidewalks. There was no evidence to

FN2. The Police Chief of Columbia testi- suggest that these onlookers were anything but curi-

fied that about 15 of his men were present, ous, and no evidence at all of any threatening re-

and that there were, in addition, ‘some marks, hostile gestures, or offensive language on

State Highway Patrolmen; there were some the part of any member of the crowd. The City

South Carolina Law Enforcement officers Manager testified that he recognized some of the

present and I believe, I'm not positive, I onlookers, whom he did not identify, as ‘possible

believe there were about three Deputy trouble makers,’ but his subsequent testimony made

Sheriffs.’ clear that nobody among the crowd actually caused

FN4

or threatened any trouble. There was no ob-

FN3. The Police Chief of Columbia testi- struction of pedestrian*232 or vehicular**682

FN5

fied as follows: traffic within the State House grounds. No

vehicle was prevented from entering or leaving the

‘Q. Did you, Chief, walk around the State horseshoe area. Although vehicular traffic at a

House Building with any of these persons? nearby street intersection was slowed down some-

what, an officer was dispatched to keep traffic mov-

‘A. I did not. I stayed at the horseshoe. I

ing. There were a number of bystanders on the pub-

placed men over the grounds.

lic sidewalks adjacent to the State House grounds,

‘Q. Did any of your men make a report that but they all moved on when asked to do so, and

FN6

any of these persons were disorderly in there was no impediment of pedestrian traffic.

walking around the State House Grounds? Police protection at the scene was at all *233 times

sufficient to meet any foreseeable possibility of dis-

FN7

‘A. They did not. order.

‘Q. Under normal circumstances your men FN4. ‘Q. Who were those persons?

would report to you when you are at the

scene? ‘A. I can't tell you who they were. I can

tell you they were present in the group.

‘A. They should. They were recognized as possible trouble

makers.

‘Q. Is it reasonable to assume then that

there was no disorderly conduct on the part ‘Q. Did you and your police chief do any-

of these persons, since you received no re- thing about placing those people under ar-

port from your officers? rest?

‘A. I would take that for granted, yes.’ ‘A. No, we had no occasion to place them

under arrest.

The City Manager testified:

‘Q. Now, sir, you have stated that there

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 4

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

were possible trouble makers and your ‘Q. So that nobody complained that he

whole testimony has been that, as City wanted to use the sidewalk and he could

Manager, as supervisor of the City Police, not do it?

your object is to preserve the peace and

law and order? ‘A. I didn't have any complaints on that.’

‘A. That's right. FN7. The City Manager testified:

‘Q. Yet you took no official action against ‘Q. You had ample time, didn't you, to get

people who were present and possibly ample police protection, if you thought

might have done some harm to these such was needed on the State House

people? grounds, didn't you?

‘A. We took no official action because ‘A. Yes, we did.

there was none to be taken. They were not

‘Q. So, if there were not ample police pro-

creating a disturbance, those particular

tection there, it was the fault of those per-

people were not at that time doing any-

sons in charge of the Police Department,

thing to make trouble but they could have

wasn't it?

been.’

‘A. There was ample police protection

FN5. The Police Chief of Columbia testi-

there.’

fied:

In the situation and under the circumstances thus

‘Q. Each group of students walked along in

described, the police authorities advised the peti-

column of twos?

tioners that they would be arrested if they did not

FN8

‘A. Sometimes two and I did see some in disperse within 15 minutes. Instead of dispers-

single-file. ing, the petitioners engaged in what the City Man-

ager described as ‘boisterous,’ ‘loud,’ and

‘Q. There was ample room for other per- ‘flamboyant’ conduct, which, as his later testimony

sons going in the same direction or the op- made clear, consisted of listening to a ‘religious

posite direction to pass on the same side- harangue’ by one of their leaders, and loudly

walk? singing ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ and other patri-

otic and religious songs, while stamping their feet

‘A. I wouldn't say they were blocking the and clapping their hands. After 15 minutes had

sidewalk; now, that was through the State passed, the police arrested the petitioners and

House grounds.’ FN9

marched them off to jail.

FN6. The Police Chief of Columbia testi- FN8. The City Manager testified:

fied:

‘Q. Mr. McNayr, what action did you take?

‘A. At times they blocked the sidewalk and

we asked them to move over and they did. ‘A. I instructed Dave Carter to tell each of

these groups, to call them up and tell each

‘Q. They obeyed your commands on that? of the groups and the group leaders that

they must disperse, they must disperse in

‘A. Yes.

the manner which I have already de-

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 5

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

scribed, that I would give them fifteen ally broken to lay the foundation for a prosecution

minutes from the time of my conversation for this offense. If what is done is unjustifiable and

with him to have them dispersed and, if unlawful, tending with sufficient directness to

they were not dispersed, I would direct my break the peace, no more is required. Nor is actual

Chief of Police to place them under arrest.’ personal violence an essential element in the of-

fense. * * *

FN9. The City Manager testified:

‘By ‘peace,’ as used in the law in this connection, is

‘Q. You have already testified, Mr. meant the tranquility enjoyed by citizens of a muni-

McNayr, I believe, that you did order these cipality or community where good order reigns

students dispersed within fifteen minutes? among its members, which is the natural right of all

persons in political society.' 239 S.C., at 343-344,

‘A. Yes.

123 S.E.2d, at 249.

‘Q. Did they disperse in accordance with

[1][2] The petitioners contend that there was a com-

your order?

plete absence of any evidence of the commission of

‘A. They did not. this offense, and that they were thus denied one of

the most basic elements*235 of due process of

‘Q. What then occurred? law. Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199, 80

S.Ct. 624, 4 L.Ed.2d 654; see Garner v. Louisiana,

‘A. I then asked Chief of Police Campbell 368 U.S. 157, 82 S.Ct. 248, 7 L.Ed.2d 207; Taylor

to direct his men to line up the students v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154, 82 S.Ct. 1188, 8

and march them or place them under arrest L.Ed.2d 395. Whatever the merits of this conten-

and march them to the City Jail and the tion, we need not pass upon it in the present case.

County Jail. The state courts have held that the petitioners' con-

duct constituted breach of the peace under state

‘Q. They were placed under arrest?

law, and we may accept their decision as binding

‘A. They were placed under arrest.’ upon us to that extent. But it nevertheless remains

our duty in a case such as this to make an independ-

*234 Upon this evidence the state trial court con- ent examination of the whole record. Blackburn v.

victed the petitioners of breach of the peace, and Alabama, 361 U.S. 199, 205, n. 5, 80 S.Ct. 274,

imposed sentences ranging from a $10 fine or five 279, 4 L.Ed.2d 242; Pennekamp v. Florida, 328

days in jail, to a $100 fine or 30 days in jail. In af- U.S. 331, 335, 66 S.Ct. 1029, 1031, 90 L.Ed. 1295;

firming the judgments, the Supreme Court of South Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U.S. 380, 385-386, 47 S.Ct.

Carolina said that under the law of that State the of- 655, 656-657, 71 L.Ed. 1108. And it is clear to us

fense of breach of the **683 peace ‘is not suscept- that in arresting, convicting, and punishing the peti-

ible of exact definition,’ but that the ‘general defin- tioners under the circumstances disclosed by this

ition of the offense’ is as follows: record, South Carolina infringed the petitioners'

constitutionally protected rights of free speech, free

‘In general terms, a breach of the peace is a viola- assembly, and freedom to petition for redress of

tion of public order, a disturbance of the public their grievances.

tranquility, by any act or conduct inciting to viol-

ence * * *, it includes any violation of any law en- [3] It has long been established that these First

acted to preserve peace and good order. It may con- Amendment freedoms are protected by the Four-

sist of an act of violence or an act likely to produce teenth Amendment from invasion by the States.

violence. It is not necessary that the peace be actu- Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652, 45 S.Ct. 625,

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 6

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

69 L.Ed. 1138; Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. barren of any evidence of ‘fighting words.’ See

357, 47 S.Ct. 641, 71 L.Ed. 1095; Stromberg v. Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 62

California, 283 U.S. 359, 51 S.Ct. 532, 75 L.Ed. S.Ct. 766, 86 L.Ed. 1031.

1117; De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 57 S.Ct.

255, 81 L.Ed. 278; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 We do not review in this case criminal convictions

U.S. 296, 60 S.Ct. 900, 84 L.Ed. 1213. The circum- resulting from the evenhanded application of a pre-

stances in this case reflect an exercise of these basic cise and narrowly drawn regulatory statute evincing

constitutional rights in their most pristine and clas- a legislative judgment that certain specific conduct

sic form. The petitioners felt aggrieved by laws of be limited or proscribed. If, for example, the peti-

South Carolina which allegedly ‘prohibited Negro tioners had been convicted upon evidence that they

privileges in this State.’ They peaceably assembled had violated a law regulating traffic, or had dis-

FN10 obeyed a law reasonably limiting the periods during

at the site of the State Government and there

peaceably expressed their grievances ‘to the cit- which the State House grounds were open to the

FN11

izens of South Carolina, along with the Legislative public, this would be a different case. *237

Bodies of South Carolina.’ *236 Not until they See Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296,

were told by police officials that they must disperse 307-308, 60 S.Ct. 900, 904-905, 84 L.Ed. 1213;

on pain of arrest did they do more. Even then, they Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157, 202, 82 S.Ct.

but sang patriotic and religious songs after one of 248, 271, 7 L.Ed.2d 207 (concurring opinion).

their leaders had delivered a ‘religious harangue.’ These petitioners were convicted of an offense so

**684 There was no violence or threat of violence generalized as to be, in the words of the South Car-

on their part, or on the part of any member of the olina Supreme Court, ‘not susceptible of exact

crowd watching them. Police protection was definition.’ And they were convicted upon evidence

‘ample.’ which showed no more than that the opinions which

they were peaceably expressing were sufficiently

FN10. It was stipulated at trial ‘that the opposed to the views of the majority of the com-

State House grounds are occupied by the munity to attract a crowd and necessitate police

Executive Branch of the South Carolina protection.

government, the Legislative Branch and

the Judicial Branch, and that, during the FN11. Section 1-417 of the 1952 Code of

period covered in the warrant in this mat- Laws of South Carolina (Cum.Supp.1960)

ter, to wit: March the 2nd, the Legislature provides as follows:

of South Carolina was in session.’

‘It shall be unlawful for any person:

This, therefore, was a far cry from the situation in

‘(1) Except State officers and employees

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315, 71 S.Ct. 303, 95

and persons having lawful business in the

L.Ed. 295, where two policemen were faced with a

buildings, to use any of the driveways, al-

crowd which was ‘pushing, shoving and milling

leys or parking spaces upon any of the

around,’ id., at 317, 71 S.Ct. at 305, where at least

property of the State, bounded by As-

one member of the crowd ‘threatened violence if

sembly, Gervais, Bull and Pendleton

the police did not act,’ id., at 317, 71 S.Ct. at 305,

Streets in Columbia upon any regular

where ‘the crowd was pressing closer around peti-

weekday, Saturdays and holidays excepted,

tioner and the officer,’ id., at 318, 71 S.Ct. at 305,

between the hours of 8:30 a.m. and 5:30

and where ‘the speaker passes the bounds of argu-

p.m., whenever the buildings are open for

ment or persuasion and undertakes incitement to ri-

business; or

ot.’ Id., at 321, 71 S.Ct. at 306. And the record is

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 7

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

‘(2) To park any vehicle except in the California, ‘The maintenance of the opportunity for

spaces and manner marked and designated free political discussion to the end that government

by the State Budget and Control Board, in may be responsive to the will of the people and that

cooperation with the Highway Department, changes may be obtained by lawful means, an op-

or to block or impede traffic through the portunity essential to the security of the Republic,

alleys and driveways.’ is a fundamental principle of our constitutional sys-

tem. A statute which upon its face, and as authorit-

The petitioners were not charged with viol- atively construed, is so vague and indefinite as to

ating this statute, and the record contains permit the punishment of the fair use of this oppor-

no evidence whatever that any police offi- tunity is repugnant to the guaranty of liberty con-

cial had this statute in mind when ordering tained in the Fourteenth Amendment. * * *’ 283

the petitioners to disperse on pain of arrest, U.S. 359, 369, 51 S.Ct. 532, 536, 75 L.Ed. 1117.

or indeed that a charge under this statute

could have been sustained by what oc- For these reasons we conclude that these criminal

curred. convictions cannot stand.

[4] The Fourteenth Amendment does not permit a Reversed.

State to make criminal the peaceful expression of

unpopular views. ‘(A) function of free speech under Mr. Justice CLARK, dissenting.

our system of government is to invite dispute. It The convictions of the petitioners, Negro high

may indeed best serve its high purpose when it in- school and college students, for breach of the peace

duces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction under South Carolina law are accepted by the Court

with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to ‘as binding upon us to that extent’ but are held viol-

anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. ative of ‘petitioners' constitutionally protected

It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and rights of free speech, free assembly, and freedom to

have profound unsettling effects as it presses for ac- petition for redress of their grievances.’ Petitioners,

ceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech of course, had a right to peaceable assembly, to es-

* * * is * * * protected against censorship or pun- pouse their cause and to petition, but in my view

ishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and the manner in which they exercised those rights

present danger of a serious substantive evil that was by no means the passive demonstration which

rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or this Court relates; rather, as the City Manager of

unrest. * * * There is no room under our Constitu- Columbia *239 testified, ‘a dangerous situation was

tion for a more restrictive*238 view. For the altern- really building up’ which South Carolina's courts

ative would lead to standardization of ideas either expressly found had created ‘an actual interference

by legislatures, courts, or **685 dominant political with traffic and an imminently threatened disturb-

FN1

or community groups.’ Terminiello v. Chicago, ance of the peace of the community.' Since the

337 U.S. 1, 4-5, 69 S.Ct. 894, 896, 93 L.Ed. 1131. Court does not attack the state courts' findings and

As in the Terminiello case, the courts of South Car- accepts the convictions as ‘binding’ to the extent

olina have defined a criminal offense so as to per- that the petitioners' conduct constituted a breach of

mit conviction of the petitioners if their speech the peace, it is difficult for me to understand its un-

‘stirred people to anger, invited public dispute, or derstatement of the facts and reversal of the convic-

brought about a condition of unrest. A conviction tions.

resting on any of those grounds may not stand.’

FN1. Unreported order of the Richland

Id., at 5, 69 S.Ct., at 896.

County Court, July 10, 1961, on appeal

[5] As Chief Justice Hughes wrote in Stromberg v. from the Magistrate's Court of Columbia,

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 8

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

South Carolina. The Supreme Court's af- problems resulting from petitioners' activities. It

firmance of that order, 239 S.C. 339, 123 was only after the large crowd had gathered, among

S.E.2d 247, is now before us on writ of which the City Manager and Chief of Police recog-

certiorari. nized potential troublemakers, and which together

with the students had become masse don and

The priceless character of First Amendment around the ‘horseshoe’ so closely that vehicular and

freedoms cannot be gainsaid, but it does not follow FN3

pedestrian traffic was materially impeded, *241

that they are absolutes immune from necessary state that any action against the petitioners was taken.

action reasonably designed for the protection of so- Then the City Manager, in what both the state inter-

ciety. See Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296, mediate and Supreme Court found to be the utmost

304, 60 S.Ct. 900, 903, 84 L.Ed. 1213 (1940); good faith, decided that danger to peace and safety

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147, 160, 60 S.Ct. 146, was imminent. Even at this juncture no orders were

150, 84 L.Ed. 155 (1939). For that reason it is our issued by the City Manager for the police to break

duty to consider the context in which the arrests up the crowd, now about 500 persons, and no ar-

here were made. Certainly the city officials would rests were made. Instead, he approached the recog-

be constitutionally prohibited from refusing peti- nized leader of the petitioners and requested him to

tioners access to the State House grounds merely tell the various groups of petitioners to disperse

because they disagreed with their views. See within 15 minutes, failing which they would be ar-

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268, 71 S.Ct. 325, rested. Even though the City Manager might have

328, 95 L.Ed. 267, 280 (1951). But here South Car- been honestly mistaken as to the imminence of

olina's courts have found: ‘There is no indication danger, this was certainly a reasonable request by

whatever in this case that the acts of the police of- the city's top executive officer in an effort to avoid

ficers were taken as a subterfuge or excuse for the a public brawl. But the response of petitioners and

suppression of the appellants' views and opinions.' their leader was defiance rather than cooperation.

FN2

It is undisputed that the city officials specific- The leader immediately moved from group to group

ally granted petitioners permission to assemble, im- among the students, delivering a ‘harangue’ which,

posing only the requirement that they be ‘peaceful.’ according to testimony in the record, ‘aroused

Petitioners then gathered on the State **686 House (them) to a fever pitch causing this boisterousness,

grounds, during a General Assembly session, in a this singing and stomping.’

large number of almost 200, marching and carrying

placards with slogans *240 such as ‘Down with se- FN3. The City Manager testified as fol-

gregation’ and ‘You may jail our bodies but not our lows:

souls.’ Some of them were singing.

‘Q. Now, with relation, Mr. McNayr, to the

FN2. Supra, note 1. sidewalks around the horseshoe and the

lane for vehicular traffic, how was the

The activity continued for approximately 45 crowd distributed, with regard to those

minutes, during the busy noon-hour period, while a sidewalks and roadways?

crowd of some 300 persons congregated in front of

the State House and around the area directly in ‘A. Well, the conditions varied from time

front of its entrance, known as the ‘horseshoe,’ to time, but at numerous times they were

which was used for vehicular as well as pedestrian blocked almost completely with probably

ingress and egress. During this time there were no as many as thirty or forty persons, both on

efforts made by the city officials to hinder the peti- the sidewalks and in the street area. * * *

tioners in their rights of free speech and assembly;

rather, the police directed their efforts to the traffic ‘Q. Did you observe the pedestrian traffic

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 9

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

on the walkway? tion, the enlargement of constitutional protection

for the conduct here is as fallacious as would be the

‘A. Yes, I did. conclusion that free speech necessarily includes the

right to broadcast from a sound truck in the public

‘Q. What was the condition there?

streets. Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U.S. 77, 69 S.Ct.

‘A. The condition there was that it was ex- 448, 93 L.Ed. 513 (1949). This Court said in

tremely difficult for a pedestrian wanting Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 105, 60 S.Ct.

to get through, to get through. Many of 736, 745, 84 L.Ed. 1093 (1940), that ‘(t)he power

them took to the street area, even to get and the duty of the State to take adequate steps to

through the street area or the sidewalk.’ preserve the peace and to protect the privacy, the

lives, and the property of its residents cannot be

The Chief of Police testified as follows: doubted.’ Significantly, in holding that the petition-

er's picketing was constitutionally protected in that

‘Q. Was the street blocked? case the Court took pains to differeniate it from

‘picketing en masse or otherwise conducted which

‘A. We had to place a traffic man at the in-

might occasion * * * imminent and aggravated

tersection of Gervais and Main to handle

danger * * *.’ Ibid. Here the petitioners were per-

traffic and pedestrians.

mitted without hindrance to exercise their rights of

‘Q. Was a vehicular traffic lane blocked? free speech and assembly. Their arrests occurred

only after a situation arose in which the law-

‘A. It was, that was in the horseshoe.’ enforcement officials on the scene considered that a

FN4

dangerous disturbance was imminent. The

For the next 15 minutes the petitioners sang ‘I Shall County Court found that ‘(t)he evidence*243 is

Not Be Moved’ and various religious songs, clear that the officers were motivated solely by a

stamped their feet, clapped their hands, and conduc- proper concern for the preservation of order and the

ted what the South Carolina Supreme Court found protection of the general welfare in the face of an

to be a ‘noisy demonstration in defiance of (the dis- actual interference with traffic and an imminently

persal) orders.’ 239 S.C. 339, 345, 123 S.E.2d 247, threatened disturbance of the peace of the com-

250. Ultimately, the petitioners were arrested, as FN5

munity.' In affirming, the South Carolina Su-

they apparently planned from the beginning, and preme Court said the action of the police was

convicted on evidence the sufficiency of which the ‘reasonable and motivated solely by a proper con-

Court does not challenge. The question thus seems cern for the preservation of order and prevention of

to me whether a State is constitutionally prohibited further interference with traffic upon the public

from enforcing laws to prevent breach of the peace streets and sidewalks.’ 239 S.C. 339, at 345, 123

in a situation where city officials in good faith be- S.E.2d, at 249-250.

lieve, and the record shows, that disorder and viol-

ence are **687 imminent, merely because the activ- FN4. The City Manager testified as fol-

ities constituting that breach contain claimed ele- lows:

ments of constitutionally protected speech *242 and

assembly. To me the answer under our cases is ‘Q. Did you hear any singing, chanting or

clearly in the negative. anything of that nature from the student

group?

Beginning, as did the South Carolina courts, with

the premise that the petitioners were entitled to as- ‘A. Yes.

semble and voice their dissatisfaction with segrega-

‘Q. Describe that as best you can.

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 10

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

‘A. With the harangues, which I have just horting adults. Here 200 youthful Negro demon-

described, witnessed frankly by everyone strators were being aroused to a ‘fever pitch’ before

present and in this area, the students began a crowd of some 300 people who undoubtedly were

answering back with shouts. They became hostile. Perhaps their speech was not so animated

boisterous. They stomped their feet. They but in this setting their actions, their placards read-

sang in loud voices to the point where, ing ‘You may jail our bodies but not our souls' and

again, in my judgment, a dangerous situ- their chanting of ‘I Shall Not Be Moved,’ accom-

ation was really building up.’ panied by stamping feet and clapping hands, cre-

ated a much greater danger of riot and disorder. It is

The Police Chief testified as follows: my belief that anyone conversant with the almost

spontaneous combustion in some Southern com-

‘Q. Chief, you were questioned on cross

munities in such a situation will agree that the City

examination at length about the appearance

Manager's action may well have averted a major

and orderliness of the student group. Were

catastrophe.

they orderly at all times?

The gravity of the danger here surely needs no fur-

‘A. Not at the last.

thre explication. The imminence of that danger has

‘Q. Would you describe the activities at been emphasized at every stage of this proceeding,

the last? from the complaints charging that the demonstra-

tions ‘tended directly to immediate violence’ to the

‘A. As I have stated, they were singing State Supreme Court's affirmance on the authority

and, also, when they were getting certain of Feiner, supra. This record, then, shows no steps

instructions, they were very loud and bois- backward from a standard of ‘clear and present

terous.’ danger.’ But to say that the police may not inter-

vene until the riot has occurred is like keeping out

FN5. Supra, note 1. the doctor until the patient dies. I cannot subscribe

to such a doctrine. In the words of my Brother

In Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra, 310 U.S. at 308,

Frankfurter:

60 S.Ct. at 905, this Court recognized that ‘(w)hen

clear and present danger of riot, disorder, interfer- ‘This Court has often emphasized that in the exer-

ence with traffic upon the public streets, or other cise of our authority over state court decisions the

immediate threat to public safety, peace, or order, Due Process Clause must not be construed in an ab-

appears, the power of the state to prevent or punish stract and doctrinaire way by disregarding local

is obvious.’ And in Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. conditions. * * * It is pertinent, therefore, to note

315, 71 S.Ct. 303, 95 L.Ed. 267 (1951), we upheld that all members of the New York Court accepted

a conviction for breach of the peace in a situation the finding that Feiner was stopped not because the

no more dangerous than that found here. There the listeners or police officers disagreed with his views

demonstration was conducted by only one person but because these officers were honestly concerned

and the crowd was limited to approximately 80, as with preventing a breach of the peace. * * *

compared with the present lineup of some 200

demonstrators and 300 onlookers. There the peti- *245 ‘As was said in Hague v. C.I.O. (307 U.S.

tioner was ‘endeavoring to arouse the Negro people 496, 59 S.Ct. 954, 83 L.Ed. 1423), supra, uncon-

against the whites, urging that they rise up in arms trolled official suppression of the speaker ‘cannot

and fight for equal rights.’ Id., at 317, 71 S.Ct. at be made a substitute for the duty to maintain order’.

305. Only one person-in a city having an entirely 307 U.S. at 516, 59 S.Ct. at page 964, 83 L.Ed.

dif**688 ferent*244 historical background-was ex- 1423. Where conduct is within the allowable limits

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

83 S.Ct. 680 Page 11

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

(Cite as: 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680)

of free speech, the police are peace officers for the

speaker as well as for his hearers. But the power ef-

fectively to preserve order cannot be displaced by

giving a speaker complete immunity. Here, there

were two police officers present for 20 minutes.

They interfered only when they apprehended im-

minence of violence. It is not a constitutional prin-

ciple that, in acting to preserve order, the police

must proceed against the crowd, whatever its size

and temper, and not against the (demonstrators).'

340 U.S. 268, at 288-289, 71 S.Ct. 328, at 336, 95

L.Ed. 295 (concurring opinion in Feiner v. New

York and other cases decided that day).

I would affirm the convictions.

U.S.S.C. 1963.

Edwards v. South Carolina

372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697

END OF DOCUMENT

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

You might also like

- Jackson Cert Opp Brief WesternSkyFinancial v. D.jacksonDocument42 pagesJackson Cert Opp Brief WesternSkyFinancial v. D.jacksonThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Coolidge v. New Hampshire - 403 U.S. 443 (1971)Document49 pagesCoolidge v. New Hampshire - 403 U.S. 443 (1971)Thalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Washington Post EXPRESS - 12032010Document40 pagesWashington Post EXPRESS - 12032010Thalia SandersNo ratings yet

- W.O.W. Evite 5x7 v4 FINALDocument1 pageW.O.W. Evite 5x7 v4 FINALThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Daily Kos - Hey America! Can You Please Stop Killing Our (Usually) Innocent Black Male Children NowDocument88 pagesDaily Kos - Hey America! Can You Please Stop Killing Our (Usually) Innocent Black Male Children NowThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Bulletin 67 PHILJADocument32 pagesBulletin 67 PHILJABeverly FGNo ratings yet

- Petition For BailDocument5 pagesPetition For BailAw LapuzNo ratings yet

- Barrientos vs. Atty. LibiranDocument22 pagesBarrientos vs. Atty. LibiranMatias WinnerNo ratings yet

- United States v. Candelas, 10th Cir. (2011)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Candelas, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 6 Galman Vs PamaranDocument2 pages6 Galman Vs PamaranJeah N MelocotonesNo ratings yet

- 4 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES Plaintiff Appellee vs. RENATO DADULLA y CAPANASDocument16 pages4 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES Plaintiff Appellee vs. RENATO DADULLA y CAPANASMartin Tongco FontanillaNo ratings yet

- NYC Public Advocate Corrections Committee DOCCS Testimony 12.2.15Document5 pagesNYC Public Advocate Corrections Committee DOCCS Testimony 12.2.15Rachel SilbersteinNo ratings yet

- Ass 1 - Jan. 26 2019Document42 pagesAss 1 - Jan. 26 2019De Guzman E AldrinNo ratings yet

- Discovery Petition Mary BlairDocument18 pagesDiscovery Petition Mary BlairABC7NewsNo ratings yet

- Factories Act, 1948 PDFDocument72 pagesFactories Act, 1948 PDFCPCNo ratings yet

- 13 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument13 pages13 - Chapter 4 PDFj.r.g.shomanathNo ratings yet

- Offender Profiling PDFDocument368 pagesOffender Profiling PDFAnonymous lsnDTjvNo ratings yet

- Anti SLAPP Motion Gerald Waldman Vs Capitol Intelligence Group Libel and Slander Civil Action Case No. 2018-CA-005052Document42 pagesAnti SLAPP Motion Gerald Waldman Vs Capitol Intelligence Group Libel and Slander Civil Action Case No. 2018-CA-005052CapitolIntelNo ratings yet

- USA V BHIDE Agreed MotionDocument4 pagesUSA V BHIDE Agreed MotionAmanda HugankissNo ratings yet

- Free Legal Aid in IndiaDocument30 pagesFree Legal Aid in Indiamandarlotlikar0% (1)

- Treason Claims Brought Against 3rd Federal Judge Tied To $42B Lawsuit, Harihar V US BankDocument48 pagesTreason Claims Brought Against 3rd Federal Judge Tied To $42B Lawsuit, Harihar V US BankMohan HariharNo ratings yet

- Natural Law Cases 2 Full TextDocument63 pagesNatural Law Cases 2 Full TextGlenda Mae GemalNo ratings yet

- Zalameda v. PeopleDocument4 pagesZalameda v. PeopleAnonymous wDganZNo ratings yet

- CHRDocument250 pagesCHRWresen AnnNo ratings yet

- United States of America v. Contents of Bank of America Account Numbers Et Al - Document No. 6Document2 pagesUnited States of America v. Contents of Bank of America Account Numbers Et Al - Document No. 6Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Weekly ChemerutDocument3 pagesWeekly ChemerutPending_nameNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument29 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRuzzel Diane Irada Oducado100% (3)

- 5-23-2018 - Motion For Reasonable BondDocument1 page5-23-2018 - Motion For Reasonable BondMark RemillardNo ratings yet

- 2 Pop Vs Castor Batin Personal DigestDocument4 pages2 Pop Vs Castor Batin Personal Digestvincent remolacio100% (1)

- Guanzon Vs de VillaDocument2 pagesGuanzon Vs de VillaSyed Almendras IINo ratings yet

- Nagaland Jhumland Act 1970Document15 pagesNagaland Jhumland Act 1970Latest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

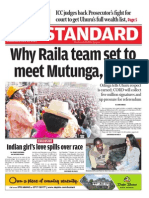

- The Standard - 2014-07-30Document71 pagesThe Standard - 2014-07-30jorina8070% (1)

- A.M. No. 10-5-7-SC December 7, 2010 Jovito S. Olazo, Justice Dante O. Tinga (Ret.)Document4 pagesA.M. No. 10-5-7-SC December 7, 2010 Jovito S. Olazo, Justice Dante O. Tinga (Ret.)gerrymanderingNo ratings yet

- Lumanog vs. PeopleDocument6 pagesLumanog vs. PeopleAnakataNo ratings yet

- United States v. Sebastion Della Universita., 298 F.2d 365, 2d Cir. (1962)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Sebastion Della Universita., 298 F.2d 365, 2d Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet