Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology: Gary M Feinman, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL, USA

Uploaded by

armando nicolau romeroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology: Gary M Feinman, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL, USA

Uploaded by

armando nicolau romeroCopyright:

Available Formats

Author's personal copy

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology

Gary M Feinman, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL, USA

2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Abstract

Settlement pattern archaeology and the investigation of ancient landscapes, especially when systematically implemented,

have been some of the most signicant archaeological innovations of the last half century. These studies have shed new light

on the emergence of hierarchically organized and urban societies in regions around the world, while also providing new

perspectives on the history of humanenvironmental interactions. This article reviews the roots of these regional archaeological approaches, their theoretical underpinnings, and some of the key empirical contributions.

Settlement pattern and landscape approaches are central to the

mission of contemporary archaeology (Kowalewski, 2008;

Renfrew, 2003, p. 313; Sabloff and Ashmore, 2001, p. 14).

Through archaeological surveys, they provide a regional

perspective on behavioral change that has been key to the

transition from normative to relational or populational

perspectives on the past. Although these studies have had

the greatest impact on the understanding of arid and

semiarid areas, they have been employed under a range

of conditions. There is no correct way to survey; however,

methodological procedures and analytical strategies must

be guided by environmental conditions, available resources,

and research goals. The most successful studies to date have

been those in which signicant and sustained time and labor

investments have been made.

For contemporary archaeology, settlement and landscape

approaches represent an increasingly important focus that is

vital for a core mission of the discipline to describe, understand, and explain long-term cultural and behavioral changes.

Despite this signicance, relatively few syntheses of this topic

have been undertaken (cf Ammerman, 1981; Billman and

Feinman, 1999; Fish and Kowalewski, 2009; Kowalewski,

2008; Parsons, 1972). Yet settlement and landscape

approaches provide the only large-scale perspective for the

majority of premodern societies. These studies are reliant on

archaeological surface surveys, which discover and record the

distribution of material traces of past human presence/habitation across a landscape (see Survey and Excavation (Field

Methods) in Archaeology). The examination and analysis of

these physical remains found on the ground surface (e.g.,

potsherds, stone artifacts, house foundations, or earthworks)

provide the empirical foundation for the interpretation of

ancient settlement patterns and landscapes.

the landscape approach, which has a more focal emphasis

on the relationship between sites and their physical

environments, has its roots in the United Kingdom.

Nevertheless, contemporary archaeological studies indicate

a high degree of intellectual cross-fertilization between these

different surface approaches.

Early Foundations for Archaeological Survey in the Americas

and England

The American settlement pattern tradition stems back

to scholars such as Morgan (1881), who queried how the

remnants of Native American residential architecture reected

the social organization of the native peoples who occupied

them. Yet the questions posed by Morgan led to relatively

few immediate changes in how archaeology was practiced,

and for several decades few scholars endeavored to address

the specic questions regarding the relationship between

settlement and social behavior that Morgan posed. When

surface reconnaissance was undertaken by archaeologists, it

tended to be a largely unsystematic exercise carried out to

nd sites worthy of excavation.

In the United Kingdom, the landscape approach, pioneered by Fox (1923), was more narrowly focused on the

denition of distributional relationships between different

categories of settlements and environmental features (e.g.,

soils, vegetation, and topography). Often, these early studies

relied on and summarized surveys and excavations that were

carried out by numerous investigators using a variety of eld

procedures rather than more uniform or systematic coverage

implemented by a single research team. At the same time,

the European landscape tradition generally has had a closer

link to romantic thought as opposed to the more positivistic

roots of the North American settlement pattern tradition

(e.g., Sherratt, 1996).

Historical Background

Although the roots of settlement pattern and landscape

approaches extend back to the end of the nineteenth

century, archaeological survey has only come into its own

in the post-World War II era. Spurred by the analytical

emphases of Steward (1938), Willeys Vir Valley

Archaeological Survey (1953) provided a key impetus for

settlement pattern research in the Americas. In contrast,

654

The Development of Settlement Archaeology

By the 1930s and 1940s, US archaeologists working in several

global regions recognized that changing patterns of social

organization could not be reconstructed and interpreted

through empirical records that relied exclusively on the excavation of a single site or community within a specic region.

For example, in the lower Mississippi Valley, Phillips et al.

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, Volume 21

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.13041-7

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 654658

Author's personal copy

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology

(1951) located and mapped archaeological sites across a large

area to analyze shifting patterns of ceramic styles and

settlements over broad spatial domains and temporal contexts.

Yet the most inuential and problem-focused investigation

of that era was that of Willey in the Vir Valley. Willeys project

was the rst to formally elucidate the scope and potential

analytical utility of settlement patterns for understanding

long-term change in human economic and social relationships. His vision moved beyond the basic correlation of

environmental features and settlements as well as beyond the

mere denition of archetypical settlement types for a given

region. In addition to its theoretical contributions, the Vir

program also was innovative methodologically, employing

(for the rst time in the Western Hemisphere) vertical air

photographs in the location and mapping of ancient settlements. Although Willey did not carry out his survey entirely

on foot, he did achieve reasonably systematic areal coverage

for a dened geographic domain for which he could examine

changes in the frequency of site types, as well as diachronic

shifts in settlement patterns.

Conceptually and methodologically, these early settlement

pattern projects of the 1930s and 1940s established the

intellectual underpinnings for a number of multigenerational

regional archaeological survey programs that were initiated

in at least four global regions during the 1950s and 1960s. In

many ways, these later survey programs were integral to the

theoretical and methodological reevaluations that occurred

in archaeological thought and practice under the guise of

the New Archaeology, or processualism. The latter theoretical

framework stemmed in part from an expressed emphasis on

understanding long-term processes of behavioral change and

cultural transition at the population (and so regional) scale.

This perspective, which replaced a more normative emphasis

on archetypical sites or cultural patterns, was made possible

to a signicant degree by the novel diachronic and broad scalar

vantages pieced together for specic areas through systematic

regional settlement pattern eldwork and analysis.

Large-Scale Regional Survey Programs

During the 1950s through the 1970s, major regional settlement

pattern programs were initiated in the heartlands of three areas

where early civilizations emerged (Greater Mesopotamia,

highland Mexico, and the Aegean), as well as in one area

known for its rich and diverse archaeological heritage (the

Southwest United States). The achievements of the Vir project

also stimulated continued Andean settlement pattern surveys,

although a concerted push for regional research did not take

root there until somewhat later (e.g., Billman and Feinman,

1999; Parsons et al., 1997).

Beginning in 1957, Robert M. Adams (e.g., 1965, 1981) and

his associates methodically traversed the deserts and plains of

the Near East by jeep, mapping earthen tells and other visible

sites. Based on the coverage of hundreds of square kilometers,

these pioneering studies of regional settlement history served to

unravel some of the processes associated with the early emergence of social, political, and economic complexity in Greater

Mesopotamia. Shortly thereafter, in highland Mexico, largescale, systematic surveys were initiated in the areas two largest

mountain valleys (the Basin of Mexico and the Valley

655

of Oaxaca). These two projects implemented eld-by-eld,

pedestrian coverage of some of the largest contiguous survey

regions in the world, elucidating the diachronic settlement

patterns for regions in which some of the earliest and most

extensive cities in the ancient Americas were situated (e.g.,

Blanton et al., 1993; Sanders et al., 1979). After decades, about

half of the Basin of Mexico and almost the entire Valley of

Oaxaca were traversed by foot (Balkansky, 2006).

In the Aegean, regional surveys (McDonald and Rapp, 1972;

Renfrew, 1972) were designed to place important sites with long

excavation histories in broader spatial contexts. Once again,

these investigations brought new regional vantages to areas

that already had witnessed decades of excavation and textual

analyses (Galaty, 2005). Over the same period, settlement

pattern studies were carried out in diverse ecological settings

across the US Southwest, primarily to examine the differential

distributions of archaeological sites in relation to their natural

environments, and to determine changes in the numbers and

sizes of settlements across the landscape over time. More

recently, new projects have introduced systematic, broadcoverage, archaeology settlement pattern studies to other

regions, including parts of northern China (e.g., Feinman

et al., 2010; Peterson et al., 2010; Underhill et al., 2008) and

Madagascar (Wright, 2007). In each of the global areas

investigated, the wider the study domain covered, the more

diverse and complex were the patterns found. Growth in one

part of a larger study area was often timed with the decrease

in the size and number of sites in another. And settlement

trends for given regions generally were reected in episodes of

both growth and decline.

Each of these major survey regions (including much of the

Andes) is an arid to semiarid environment. Without question,

broadscale surface surveys have been most effectively implemented in regions that lack dense ground cover, and therefore

the resultant eld ndings have been most robust. In turn, these

ndings have fomented long research traditions carried out by

trained crews, thereby contributing to the intellectual rewards of

these efforts. As Ammerman (1981, p. 74) has recognized,

major factors in the success of the projects would appear to

be the sheer volume of work done and the experience that

workers have gradually built up over the years.

Settlement Pattern Research at Smaller Scales of Analysis

Although settlement pattern approaches were most broadly

applied at the regional scale, other studies followed similar

conceptual principles in the examination of occupational

surfaces, structures, and communities. At the scale of individual

living surfaces or house oors, such distributional analyses have

provided key indications as to which activities (such as cooking,

food preparation, and toolmaking) were undertaken in different

sectors (activity areas) of specic structures (e.g., Flannery and

Winter, 1976) or surfaces (e.g., Flannery, 1986, pp. 321423).

In many respects, the current emphasis on household

archaeology (e.g., Santley and Hirth, 1993; Wilk and Rathje,

1982) is an extension of settlement pattern studies. Both

household and settlement pattern approaches have fostered

a growing interest in the nonelite sector of complex societies,

and so have spurred the effort to understand societies as more

than just undifferentiated, normative wholes.

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 654658

Author's personal copy

656

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology

At the intermediate scale of single sites or communities,

settlement pattern approaches have compared the distribution

of architectural and artifactual evidence across individual sites.

Such investigations have clearly demonstrated signicant

intrasettlement variation in the functional use of space (e.g.,

Hill, 1970), as well as distinctions in socioeconomic status and

occupational history (e.g., Blanton, 1978). From a comparative

perspective, detailed settlement pattern maps and plans of

specic sites have provided key insights into the similarities

and differences between contemporaneous cities and

communities in specic regions, as well as the elucidation of

important patterns of cross-cultural diversity (e.g., Arnauld

et al., 2012).

Contemporary Research Strategies and Ongoing

Debates

The expansion of settlement pattern and landscape approaches

over the last decades has promoted the increasing acceptance of

less normative perspectives on cultural change and diversity

across the discipline of archaeology. In many global domains,

archaeological surveys have provided a new regional-scale

(and in a few cases, macroregional-scale) vantage on past

social systems. Settlement pattern studies also have yielded

a preliminary means for estimating the parameters of

diachronic demographic change and distribution at the

scale of populations, something almost impossible to

obtain from excavations alone. Nevertheless, important

discussions continue over the environmental constraints on

implementation, the relative strengths and weaknesses of

different survey methodologies, issues of chronological

control, procedures for population estimation, and the

appropriate means for the interpretation of settlement

pattern data.

Environmental Constraints

Although systematic settlement pattern and landscape studies

have been undertaken in diverse environmental settings

including heavily vegetated locales such as the Guatemalan

Petn, the eastern woodlands of North America, and temperate

Europe, the most sustained and broadly implemented regional

survey programs to date have been enacted in arid environments. In large part, this preference pertains to the relative ease

of nding the artifactual and architectural residues of ancient

sites on the surface of landscapes that lack thick vegetal covers.

Nevertheless, archaeologists have devised a variety of means,

such as the interpolation of satellite images, the detailed

analysis of aerial photographs, and subsurface testing

programs, that can be employed to locate and map past

settlements in locales where they are difcult to nd through

pedestrian coverage alone (e.g., Chase et al., 2012). In each

study area, regional surveys also have to modify their specic

eld methodologies (the intensity of the planned coverage)

and the sizes of the areas that they endeavor to examine to

the nature of the terrain and the density of artifactual debris

(generally nonperishable ancient refuse) associated with

the sites in the specied region. For example, sedentary

pottery-using peoples generally created more garbage than

did mobile foragers; the latter usually employed more

perishable containers (e.g., baskets and cloth bags).

Consequently, other things being equal, the sites of foragers

are generally less accessible through settlement and

landscape approaches than are the ancient settlements that

were inhabited for longer durations (especially when

ceramics were used).

Survey Methodologies and Sampling

Practically since the inception of settlement pattern research,

archaeologists have employed a range of different eld survey

methods. A critical distinction has been drawn between fullcoverage and sample surveys. The former approaches rely on

the complete and systematic coverage of the study region by

members of a survey team. To ensure the full coverage of

large survey blocks, team members often space themselves

2550 m apart, depending on the specic ground cover,

the terrain, and the density of archaeological materials. As

a consequence, isolated artifact nds can occasionally be

missed. But the researchers generally can discern a reasonably

complete picture of settlement pattern change across a given

region. Alternatively, sample surveys by denition are

restricted to the investigation of only a part of (a sample of)

the study region. Frequently, such studies (because they only

cover sections of larger regions) allow for the closer spacing of

crew members.

Archaeologists have employed a range of different sampling

designs. Samples chosen for investigation may be selected

randomly or stratied by a range of diverse factors, including

environmental variables. Nevertheless, regardless of the specic

sampling designs employed, such sample surveys face the

problem of extrapolating the results from their surveyed

samples to larger target domains that are the ultimate focus of

study. Ultimately, such sample surveys have been shown to be

more successful at estimating the total number of sites in a given

study region than at dening the spacing between sites or at

discovering rare types of settlement. The appropriateness of

sample design can be decided only by the kinds of information

that the investigator aims to recover. There is no single correct

way to conduct archaeological survey, but certain methodological procedures have proved more productive in specic

contexts and given particular research aims.

Chronological Constraints and Considerations

One of the principal strengths of settlement pattern research is

that it provides a broadscale perspective on the changing

distribution of human occupation across landscapes. Yet the

precision of such temporal sequences depends on the quality

of chronological control (see Chronology, Stratigraphy, and

Dating Methods in Archaeology). The dating of sites during

surveys must depend on the recovery and temporal placement

of chronologically diagnostic artifacts from the surface of such

occupations. Artifacts found on the surface usually are already

removed from their depositional contexts. Finer chronometric

dating methods generally are of little direct utility for settlement

pattern research, since such methods are premised on

the recovery of materials in their depositional contexts. Of

course, chronometric techniques can be used in more indirect

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 654658

Author's personal copy

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology

fashion to rene the relative chronological sequences that are

derived from the temporal ordering of diagnostic artifacts

(typically pottery).

In many regions, the chronological sequences can be

rened only to periods of several hundred years in length. As

a result, sites of shorter occupational durations that may be

judged to be contemporaneous in fact could have been

inhabited sequentially. In the same vein, the size of certain

occupations may be overestimated as episodes of habitation are

conated. Although every effort should be made to minimize

such analytical errors, these problems in themselves do not

negate the general importance of the long-term regional

perspective on occupational histories that in many areas of

the world can be derived from archaeological survey alone.

Although the broad-brush perspective from surveys may never

provide the precision or detailed views that are possible from

excavation, they yield an encompassing representation at the

population scale that excavations cannot achieve. Adequate

holistic perspectives on past societies rely on the multiscalar

vantages that are provided through the integration of wideranging archaeological surveys with targeted excavations.

Population Estimation

One of the key changes in archaeological thought and conceptualization over the past half century has been the shift from

essentialist/normative thinking about ancient societies to

a more populational perspective. But the issue of how to dene

past populations, their constituent parts, and the changing

modes of interaction between those parts remains challenging

at best. Clearly, multiscalar perspectives on past social systems

are necessary to collect the basic data required to estimate areal

shifts in population size and distribution. Yet considerable

debate has been engendered over the means employed by

archaeologists to extrapolate from the density and dispersal of

surface artifacts pertaining to a specic phase to the estimated

sizes of past communities or populations.

Generally, archaeologists have relied on some combination

of the empirically derived size of a past settlement, along with

a comparative determination of surface artifact densities at that

settlement, to generate demographic estimates for a given

community. When the estimates are completed for each settlement across an entire survey region, extrapolations become

possible for larger study domains. By necessity, the specic

equations to estimate past populations vary from one region to

another because community densities are far from uniform

over time or space (e.g., Fang et al., 2004). Yet due to

chronological limitations, as well as the processes of

deposition, disturbance, and destruction, the techniques for

measuring ancient populations remain coarse-grained.

Although much renement is still needed to translate survey

data into quantitative estimates of population with a degree

of precision and accuracy, systematic regional surveys still can

provide the basic patterns of long-term demographic change

over time and space that cannot be ascertained in any other way.

The Interpretation of Regional Data

Beyond the broad-brush assessment of demographic trends and

site distribution in relation to environmental considerations,

657

archaeologists have interpreted and analyzed regional sets of

data in a variety of ways. Landscape approaches, which

began with a focused perspective on humans and their

surrounding environment, have continued in that vein, often

at smaller scales. Such studies often examine in detail the

placement of sites in a specic setting with an eye toward

landscape conservation and the meanings behind site

placement (Sherratt, 1996). At the same time, some

landscape studies have emphasized the identication of

ancient agrarian features and their construction, use, and

long-term implications for anthropogenic environmental

impacts (e.g., Fisher et al., 2009).

In contrast, other settlement pattern investigations have

employed a range of analytical and interpretive strategies. In

general, these have applied more quantitative procedures and

asked more comparatively informed questions. Over the last

40 years (e.g., Johnson, 1977), a suite of locational models

derived from outside the discipline has served as guides

against which different sets of archaeological data could be

measured and compared. Yet debates have arisen over the

underlying assumptions of such models and whether they

are appropriate for understanding the preindustrial past. For

that reason, even when comparatively close ts were achieved

between heuristically derived expectations and empirical

ndings, questions regarding equinality (similar outcomes

due to different processes) emerged. More recently, theorybuilding efforts have endeavored to rework and expand these

locational models to specically archaeological contexts with

a modicum of success. Continued work in this vein, and the

integration of some of the conceptual strengths from both

landscape and settlement pattern approaches are requisite to

understanding the complex web of relations that govern

human-to-human and human-to-environment interactions

across diverse regions over long expanses of time.

Looking Forward: The Critical Role of Settlement

Studies

The key feature and attribute of archaeology is its long

temporal panorama on human socioeconomic formations.

Understanding these formations and how they changed, diversied, and varied requires a regional/populational perspective

(as well as other vantages at other scales). Over the last century,

the methodological and interpretive tool kits necessary to

obtain this broadscale view have emerged, diverged, and

thrived. The emergence of archaeological survey (and settlement

pattern and landscape approaches) has been central to the

disciplinary growth of archaeology and its increasing ability to

address and contribute to questions of long-term societal

change. Why and how did inequality, demographic

nucleation, and concentrations of political power become

central to the current human career (see States and

Civilizations, Archaeology of) and in what ways did these

historical processes differ and parallel each other across the

globe (e.g., Peterson and Drennan, 2012; Smith et al., 2012).

Yet settlement pattern work has only relatively recently

entered the popular notion of this discipline, long wrongly

equated with and dened by excavation alone. Likewise,

many archaeologists nd it difcult to come to grips with

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 654658

Author's personal copy

658

Settlement and Landscape Archaeology

a regional perspective that has its strength in (broad) scalar

representation at the expense of specic reconstructed detail.

Finally, the potential for theoretical contributions and insights

from settlement pattern and landscape approaches (and the

wealth of data collected by such studies) has only scratched the

surface. In many respects, the growth of regional survey and

analysis represents one of the most important conceptual

developments of twentieth-century archaeology. Yet at the same

time, there are still so many mountains (literally and

guratively) to climb.

See also: Chronology, Stratigraphy, and Dating Methods in

Archaeology; States and Civilizations, Archaeology of; Survey

and Excavation (Field Methods) in Archaeology.

Bibliography

Adams, R.M., 1965. Land behind Baghdad: A History of Settlement on the Diyala Plains.

University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Adams, R.M., 1981. Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land

Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

Ammerman, A.J., 1981. Surveys and archaeological research. Annual Review of

Anthropology 10, 6388.

Arnauld, M.C., Manzanilla, L.R., Smith, M.E. (Eds.), 2012. The Neighborhood as

a Social and Spatial Unit in Mesoamerican Cities. University of Arizona Press,

Tucson, AZ.

Balkansky, A.K., 2006. Surveys and Mesoamerican archaeology: the emerging macroregional paradigm. Journal of Archaeological Research 14, 5395.

Billman, B.R., Feinman, G.M. (Eds.), 1999. Settlement Pattern Studies in the Americas:

Fifty Years since Vir. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Blanton, R.E., 1978. Monte Albn: Settlement Patterns at the Ancient Zapotec Capital.

Academic Press, New York.

Blanton, R.E., Kowalewski, S.A., Feinman, G.M., Finsten, L.M., 1993. Ancient Mesoamerica: A Comparison of Change in Three Regions, second ed. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Chase, A.F., Chase, D.Z., Fisher, C.T., Leisz, S.J., Weishampel, J.F., 2012. Geospatial

revolution and remote sensing LiDAR in Mesoamerican archaeology. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 12916

12921.

Fang, H., Feinman, G.M., Underhill, A.P., Nicholas, L.M., 2004. Settlement pattern

survey in the Rizhao area: a preliminary effort to consider Han and pre-Han

demography. Indo-Pacic Prehistory Association Bulletin 24, 7982.

Feinman, G.M., Nicholas, L.M., Fang, H., 2010. The imprint of Chinas rst emperor on

the distant realm of eastern Shandong. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences of the United States of America 107, 48514856.

Fish, S.K., Kowalewski, S.A. (Eds.), 2009. The Archaeology of Regions: A Case for Fullcoverage Survey. Percheron Press, Clinton Corners, NY.

Fisher, C.T., Hill, J.B., Feinman, G.M. (Eds.), 2009. The Archaeology of Environmental

Change: Socionatural Legacies of Degradation and Resilience. University of Arizona

Press, Tucson, AZ.

Flannery, K.V. (Ed.), 1986. Guil; Naquitz: Archaic Foraging and Early Agriculture in

Oaxaca, Mexico. Academic Press, Orlando, FL.

Flannery, K.V., Winter, M.C., 1976. Analyzing household activities. In: Flannery, K.V.

(Ed.), The Early Mesoamerican Village. Academic Press, New York, pp. 3447.

Fox, C., 1923. The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK.

Galaty, M.L., 2005. European regional studies: a coming of age? Journal of Archaeological Research 13, 291336.

Hill, J.N., 1970. Broken K Pueblo: Prehistoric Social Organization in the American

Southwest. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ.

Johnson, G.A., 1977. Aspects of regional analysis in archaeology. Annual Review of

Anthropology 6, 479508.

Kowalewski, S.A., 2008. Regional settlement pattern studies. Journal of Archaeological

Research 16, 225285.

McDonald, W.A., Rapp Jr., G.R. (Eds.), 1972. The Minnesota Messenia Expedition.

Reconstructing a Bronze Age Environment. University of Minnesota Press,

Minneapolis, MN.

Morgan, L.H., 1881. Houses and House Life of the American Aborigines. US Department

of Interior, Washington, DC.

Parsons, J.R., 1972. Archaeological settlement patterns. Annual Review of Anthropology

1, 127150.

Parsons, J.R., Hastings, C.M., Matos, R., 1997. Rebuilding the state in highland Peru:

herdercultivator interaction during the Late Intermediate period in Tarama

Chinchaycocha region. Latin American Antiquity 8, 317341.

Peterson, C.E., Lu, X., Drennan, R.D., Zhu, D., 2010. Chiey communities in Neolithic

Northeastern China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United

States of America 107, 57565761.

Peterson, C.E., Drennan, R.D., 2012. Patterned variation in regional trajectories

of community growth. In: Smith, M.E. (Ed.), The Comparative Archaeology

of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK,

pp. 88137.

Phillips, P., Ford, J.A., Grifn, J.B., 1951. Archaeological Survey in the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, 194147. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology,

Cambridge, MA.

Renfrew, C., 1972. The Emergence of Civilisation. The Cyclades and the Aegean in the

Third Millennium BC. Methuen, London.

Renfrew, C., 2003. Retrospect and prospect: Mediterranean archaeology in a new

millennium. In: Papadopoulos, J.K., Leventhal, R.M. (Eds.), Theory and Practice in

Mediterranean Archaeology. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, Los Angeles,

pp. 311318.

Sabloff, J.A., Ashmore, W., 2001. An aspect of archaeologys recent past and its

relevance in the new millennium. In: Feinman, G.M., Price, T.D. (Eds.), Archaeology

at the Millennium: A Sourcebook. Springer, New York.

Sanders, W.T., Parsons, J.R., Santley, R.S., 1979. The Basin of Mexico: Ecological

Processes in the Evolution of a Civilization. Academic Press, New York.

Santley, R.S., Hirth, K.G. (Eds.), 1993. Prehispanic Domestic Units in Western Mesoamerica. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Sherratt, A., 1996. Settlement patterns or landscape studies? Reconciling reason and

romance. Archaeological Dialogues 3, 140159.

Smith, M.E., Feinman, G.M., Drennan, R.D., Earle, T., Morris, I., 2012. Archaeology as

a social science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United

States of America 109, 76177621.

Steward, J.H., 1938. Basin Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups. Bureau of American

Ethnology, Washington, DC.

Underhill, A.P., Feinman, G.M., Nicholas, L.M., Fang, H., Luan, F., Yu, H., Cai, F.,

2008. Changes in settlement patterns and the development of complex societies

in southeastern Shandong, China. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 27,

129.

Wilk, R.R., Rathje, W.L. (Eds.), 1982. Archaeology of the Household: Building

a Prehistory of Domestic Life. American Behavioral Scientist 25 (6), 611724.

Willey, G.R., 1953. Prehistoric Settlement Patterns in the Vir Valley, Peru. Bureau of

American Ethnology, Washington, DC.

Wright, H.T., 2007. Early State Formation in Central Madagascar: An Archaeological

Survey of Western Avaradrano. Memoirs, 43. Museum of Anthropology, University of

Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Second Edition, 2015, 654658

You might also like

- Zedeño - The Archaeology of Territory and Territoriality (Arqueologia) PDFDocument8 pagesZedeño - The Archaeology of Territory and Territoriality (Arqueologia) PDFPaulo Marins GomesNo ratings yet

- Early Mesoamerican Social Transformations: Archaic and Formative Lifeways in the Soconusco RegionFrom EverandEarly Mesoamerican Social Transformations: Archaic and Formative Lifeways in the Soconusco RegionNo ratings yet

- Southeastern Mesoamerica: Indigenous Interaction, Resilience, and ChangeFrom EverandSoutheastern Mesoamerica: Indigenous Interaction, Resilience, and ChangeWhitney A. GoodwinNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Cultural Landscapes From Spac PDFDocument14 pagesMonitoring Cultural Landscapes From Spac PDFFvg Fvg Fvg100% (1)

- Paul Tolstoy - Early Sedentary Communities of The Basin of Mexico PDFDocument16 pagesPaul Tolstoy - Early Sedentary Communities of The Basin of Mexico PDFAngel Sanchez GamboaNo ratings yet

- Chalcatzingo Monument 34: A Formative Period "Southern StyleDocument9 pagesChalcatzingo Monument 34: A Formative Period "Southern Stylethule89No ratings yet

- The Artistic and Archaeological Legacy of TeotihuacanDocument29 pagesThe Artistic and Archaeological Legacy of TeotihuacanB'alam DavidNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Views of Aztec Culture: Mary G. HodgeDocument42 pagesArchaeological Views of Aztec Culture: Mary G. Hodgecicero_csNo ratings yet

- Valley of Oaxaca A Regional Setting For An Early StateDocument25 pagesValley of Oaxaca A Regional Setting For An Early StateRicardo MirandaNo ratings yet

- Painter - "Territory-Network"Document39 pagesPainter - "Territory-Network"c406400100% (1)

- Archaeological Evidence For The Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music-An Alternative Multidisciplinary PerspectiveDocument70 pagesArchaeological Evidence For The Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music-An Alternative Multidisciplinary Perspectivemilosmou100% (1)

- Early Maya Astronomy El Mirador PDFDocument23 pagesEarly Maya Astronomy El Mirador PDFcmoraguiNo ratings yet

- MacNeish, Richard & Mary W. Eubanks - Comparative Analysis of The Río Balsas and Tehuacán Models For The Origin of MaizeDocument19 pagesMacNeish, Richard & Mary W. Eubanks - Comparative Analysis of The Río Balsas and Tehuacán Models For The Origin of MaizeJesús E. Medina VillalobosNo ratings yet

- Community Formation Through Ancestral Rituals in Pre-Columbian BoliviaDocument28 pagesCommunity Formation Through Ancestral Rituals in Pre-Columbian BoliviaSetsuna NicoNo ratings yet

- The Recuay Culture of Peru S North Central Highlands A Reappraisal of Chronology and Its Implications PDFDocument27 pagesThe Recuay Culture of Peru S North Central Highlands A Reappraisal of Chronology and Its Implications PDFestefanyNo ratings yet

- 2000 Beatriz de La Fuente Olmec Sculpture The First Mesoamerican ArtDocument13 pages2000 Beatriz de La Fuente Olmec Sculpture The First Mesoamerican ArtIván D. Marifil MartinezNo ratings yet

- Willey and Sabloff 1Document22 pagesWilley and Sabloff 1Anth5334No ratings yet

- A Double-Faced Teotihuacan Style IncensarioDocument6 pagesA Double-Faced Teotihuacan Style IncensarioNumismática&Banderas&Biografías ErickNo ratings yet

- GALINDO - Gregory D. Lockard 2009 Latin American Antiquity Vol. 20 No. 2 The Occupational History of Galindo 2Document24 pagesGALINDO - Gregory D. Lockard 2009 Latin American Antiquity Vol. 20 No. 2 The Occupational History of Galindo 2carlos cevallosNo ratings yet

- Aztec Flowery Wars: Military Training, Not Human SacrificeDocument7 pagesAztec Flowery Wars: Military Training, Not Human SacrificeRex TartarorumNo ratings yet

- 1994 McCaffery MixtecaPueblaStyle.1994Document25 pages1994 McCaffery MixtecaPueblaStyle.1994Marcos MartinezNo ratings yet

- Archaeology of IdentityDocument9 pagesArchaeology of IdentityJonatan NuñezNo ratings yet

- CONKLIN, W. y J. QUILTER (Eds) - Chavín Art, Architecture, and Culture (References) - 2008Document19 pagesCONKLIN, W. y J. QUILTER (Eds) - Chavín Art, Architecture, and Culture (References) - 2008Anonymous L9rLHiDzAHNo ratings yet

- Discover the Origins of Olmec Civilization in MexicoDocument16 pagesDiscover the Origins of Olmec Civilization in MexicomiguelNo ratings yet

- Rio Azul An Ancient Maya City by Richard E. W. AdamsDocument72 pagesRio Azul An Ancient Maya City by Richard E. W. AdamsLuceroNo ratings yet

- Cyphers - OlmecaDocument28 pagesCyphers - OlmecaDaniela Grimberg100% (1)

- Embedded Andean Economic Systems and The PDFDocument58 pagesEmbedded Andean Economic Systems and The PDFHugo RengifoNo ratings yet

- Ring Le 1998Document51 pagesRing Le 1998Carolina Félix PadillaNo ratings yet

- Metadata of The Chapter That Will Be Visualized Online: TantaleánDocument9 pagesMetadata of The Chapter That Will Be Visualized Online: TantaleánHenry TantaleánNo ratings yet

- FLANNERY, Formative Oaxaca and The Zapotec Cosmos PDFDocument11 pagesFLANNERY, Formative Oaxaca and The Zapotec Cosmos PDFAnayelli Portillo Islas100% (2)

- Eagles in Mesoamerican Thought and Mytho PDFDocument27 pagesEagles in Mesoamerican Thought and Mytho PDFNarciso Meneses ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Turpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyDocument20 pagesTurpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyRob BotelloNo ratings yet

- Parsons MaryDocument10 pagesParsons MaryExakt NeutralNo ratings yet

- Las Improntas de Manos en El Arte Rupest PDFDocument28 pagesLas Improntas de Manos en El Arte Rupest PDFJose Lorenzo Encinas GarzaNo ratings yet

- Guenter - The Tomb of Kinich Janaab PakalDocument63 pagesGuenter - The Tomb of Kinich Janaab PakalAngel Sanchez GamboaNo ratings yet

- Excavations at Ticoman Village Site by American Museum 1931Document256 pagesExcavations at Ticoman Village Site by American Museum 1931Grendel MictlanNo ratings yet

- Dillehay - Huaca PrietaDocument14 pagesDillehay - Huaca PrietaMaria FarfanNo ratings yet

- Human Remains in Southern Romania from Mesolithic to ChalcolithicDocument46 pagesHuman Remains in Southern Romania from Mesolithic to ChalcolithicRaluca KogalniceanuNo ratings yet

- Antczak Et Al. (2017) Re-Thinking The Migration of Cariban-Speakers From The Middle Orinoco River To North-Central Venezuela (AD 800)Document45 pagesAntczak Et Al. (2017) Re-Thinking The Migration of Cariban-Speakers From The Middle Orinoco River To North-Central Venezuela (AD 800)Unidad de Estudios ArqueológicosNo ratings yet

- Coe. An Olmec Design On An Early Peruvian VesselDocument3 pagesCoe. An Olmec Design On An Early Peruvian VesselmiguelNo ratings yet

- State and Society at Teotihuacan Mexico (Cowgill, George)Document35 pagesState and Society at Teotihuacan Mexico (Cowgill, George)ARK MAGAZINENo ratings yet

- 2014 Martiarena LMPH DVol 1Document281 pages2014 Martiarena LMPH DVol 1Maria Farfan100% (1)

- Taube 1993Document16 pagesTaube 1993Daniel RosendoNo ratings yet

- Blood Water Vomit and Wine Pulque in May PDFDocument26 pagesBlood Water Vomit and Wine Pulque in May PDFIsus DaviNo ratings yet

- ROBERT McCAA Paleodemography of The AmericasDocument22 pagesROBERT McCAA Paleodemography of The AmericasVíctor CondoriNo ratings yet

- Aaa 2006Document35 pagesAaa 2006Vinod S RawatNo ratings yet

- Consonant Deletion, Obligatory Synharmony, Typical Suffixing: An Explanation of Spelling Practices in Mayan Writing. Written Language & Literacy 13:1 (2010), 118-179.Document0 pagesConsonant Deletion, Obligatory Synharmony, Typical Suffixing: An Explanation of Spelling Practices in Mayan Writing. Written Language & Literacy 13:1 (2010), 118-179.dmoramarinNo ratings yet

- Wari Trophy Head Discovery Expands Knowledge of Empire's PracticesDocument24 pagesWari Trophy Head Discovery Expands Knowledge of Empire's PracticesCazuja GinNo ratings yet

- Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Christopher T. Hays, Christopher T. Hays, Richard A. Weinstein, Anthony L. Ortmann, Kenneth E. Sassaman, James B. Stoltman, Tristram R. Kidder, Jon L. Gibson, Prentice Thom.pdfDocument294 pagesDr. Rebecca Saunders, Dr. Rebecca Saunders, Christopher T. Hays, Christopher T. Hays, Richard A. Weinstein, Anthony L. Ortmann, Kenneth E. Sassaman, James B. Stoltman, Tristram R. Kidder, Jon L. Gibson, Prentice Thom.pdfhotdog10100% (1)

- A Preliminary Iconographic Analysis of ADocument111 pagesA Preliminary Iconographic Analysis of AAngel Sanchez GamboaNo ratings yet

- Rock Art CaliforniaDocument28 pagesRock Art CaliforniaDiana Rocio Carvajal ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Mixtec Writing and Society. Escritura de PDFDocument450 pagesMixtec Writing and Society. Escritura de PDFJ.g.DuránNo ratings yet

- The Maya Chontal Indians of Acalan TixchelDocument616 pagesThe Maya Chontal Indians of Acalan TixchelJesus PerezNo ratings yet

- Spondylus MULLUDocument255 pagesSpondylus MULLUgabboxxxNo ratings yet

- A Long Architectural Sequence at TeotihuacánDocument8 pagesA Long Architectural Sequence at TeotihuacánNumismática&Banderas&Biografías ErickNo ratings yet

- Anthropology 1170 Mesoamerican Writing S PDFDocument11 pagesAnthropology 1170 Mesoamerican Writing S PDFMiguel Pimenta-Silva100% (1)

- Andrews Iv Shells Yucatan PDFDocument140 pagesAndrews Iv Shells Yucatan PDFDixsis KenyaNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Ornaments and Art-An Archaeological Perspective On The Origins of Behavioral Modernity JoãoDocument55 pagesThe Emergence of Ornaments and Art-An Archaeological Perspective On The Origins of Behavioral Modernity JoãosakunikaNo ratings yet

- Carol J. Mackey & Andrew J. Nelson, 2020 - Life, Death and Burial Practices During The Inca Occupation of Farfan On Peru's North Coast, Section IV PDFDocument216 pagesCarol J. Mackey & Andrew J. Nelson, 2020 - Life, Death and Burial Practices During The Inca Occupation of Farfan On Peru's North Coast, Section IV PDFCarlos Alonso Cevallos VargasNo ratings yet

- The Classic Maya Ceremonial Bar: An Iconographic AnalysisDocument39 pagesThe Classic Maya Ceremonial Bar: An Iconographic AnalysisCe Ácatl Topiltzin QuetzalcóatlNo ratings yet

- E) .Willey1953. Cap. 1. IntroductionDocument13 pagesE) .Willey1953. Cap. 1. Introductionarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- Community Archaeology General Methods AnDocument33 pagesCommunity Archaeology General Methods Anarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- Toward A Locational Definition of State Systems of Settlement - CAROLE L. CRUMLEYDocument15 pagesToward A Locational Definition of State Systems of Settlement - CAROLE L. CRUMLEYSchutzstaffelDHNo ratings yet

- The Ruins of Central America. P - Charnay, Desire p.IIDocument51 pagesThe Ruins of Central America. P - Charnay, Desire p.IIarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- (Ebook) Fine Cooking Comfort Food. 200 Delicious Recipes For Soul-Warming MealsDocument258 pages(Ebook) Fine Cooking Comfort Food. 200 Delicious Recipes For Soul-Warming Mealsarmando nicolau romero100% (3)

- Alexander 1983 Limitations Survey TechniquesDocument11 pagesAlexander 1983 Limitations Survey Techniquesarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- Pearce - Reconstructing Prehistoric Metallurgical Knowledge The Northern Italian Copper and Bronze Ages European Journal of Archaeology 1998 1 51Document21 pagesPearce - Reconstructing Prehistoric Metallurgical Knowledge The Northern Italian Copper and Bronze Ages European Journal of Archaeology 1998 1 51armando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- (Ebook) Archaeology The Geometry of Ancient Sites, W.johnsonDocument21 pages(Ebook) Archaeology The Geometry of Ancient Sites, W.johnsonarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- Thorpe - Anthropology, Archaeology, and The Origin of WarfareDocument21 pagesThorpe - Anthropology, Archaeology, and The Origin of WarfareLuis Lobato de FariaNo ratings yet

- Childe, V Gordon (1943) - Archaeology in The U.S.S.R. The Forest ZoneDocument7 pagesChilde, V Gordon (1943) - Archaeology in The U.S.S.R. The Forest Zonearmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- C) - SAA. Principles of Archaeological EthicsDocument8 pagesC) - SAA. Principles of Archaeological Ethicsarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Economic History of Europe Vol 7 Part 2 The Industrial Economies - Capital, Labour and EnterpriseDocument601 pagesThe Cambridge Economic History of Europe Vol 7 Part 2 The Industrial Economies - Capital, Labour and EnterpriseIgorCavalli100% (5)

- Battlefield ArchaeologyDocument13 pagesBattlefield Archaeologyarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- The Missing Diary of Admiral Richard E. ByrdDocument35 pagesThe Missing Diary of Admiral Richard E. Byrdarmando nicolau romero94% (69)

- Marx Childe and Trigger PDFDocument19 pagesMarx Childe and Trigger PDFarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- Climbing Self RescueDocument549 pagesClimbing Self Rescuearmando nicolau romero100% (3)

- The Missing Diary of Admiral Richard E. ByrdDocument35 pagesThe Missing Diary of Admiral Richard E. Byrdarmando nicolau romero94% (69)

- Scott Babis Haecker Fields of ConflictDocument8 pagesScott Babis Haecker Fields of Conflictarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- Abrams Bolland - Energetic Arquitectural TheoryDocument1 pageAbrams Bolland - Energetic Arquitectural Theoryarmando nicolau romeroNo ratings yet

- German Tanks of The WWII in ColorDocument97 pagesGerman Tanks of The WWII in Colorarmando nicolau romero50% (2)

- Aznar V CitibankDocument3 pagesAznar V CitibankDani LynneNo ratings yet

- New General Education Curriculum Focuses on Holistic LearningDocument53 pagesNew General Education Curriculum Focuses on Holistic Learningclaire cabatoNo ratings yet

- Seed Funding CompaniesDocument4 pagesSeed Funding Companieskirandasi123No ratings yet

- Kanter v. BarrDocument64 pagesKanter v. BarrTodd Feurer100% (1)

- UCSP Exam Covers Key ConceptsDocument2 pagesUCSP Exam Covers Key Conceptspearlyn guelaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Provisional Voter ListDocument28 pagesCorporate Provisional Voter ListtrueoflifeNo ratings yet

- Guide to Sentence Inversion in EnglishDocument2 pagesGuide to Sentence Inversion in EnglishMarina MilosevicNo ratings yet

- Pta Constitution and Bylaws FinalDocument14 pagesPta Constitution and Bylaws FinalRomnick Portillano100% (8)

- Judgment at Nuremberg - Robert ShnayersonDocument6 pagesJudgment at Nuremberg - Robert ShnayersonroalegianiNo ratings yet

- How Companies Can Flourish After a RecessionDocument14 pagesHow Companies Can Flourish After a RecessionJack HuseynliNo ratings yet

- Daimler Co Ltd v Continental Tyre and Rubber Co control and enemy characterDocument1 pageDaimler Co Ltd v Continental Tyre and Rubber Co control and enemy characterMahatama Sharan PandeyNo ratings yet

- 55850bos45243cp2 PDFDocument58 pages55850bos45243cp2 PDFHarshal JainNo ratings yet

- Yiseth Tatiana Sanchez Claros: Sistema Integrado de Gestión Procedimiento Ejecución de La Formación Profesional IntegralDocument3 pagesYiseth Tatiana Sanchez Claros: Sistema Integrado de Gestión Procedimiento Ejecución de La Formación Profesional IntegralTATIANANo ratings yet

- Final Project Taxation Law IDocument28 pagesFinal Project Taxation Law IKhushil ShahNo ratings yet

- Exercise of Caution: Read The Text To Answer Questions 3 and 4Document3 pagesExercise of Caution: Read The Text To Answer Questions 3 and 4Shantie Susan WijayaNo ratings yet

- OathDocument5 pagesOathRichard LazaroNo ratings yet

- The War Against Sleep - The Philosophy of Gurdjieff by Colin Wilson (1980) PDFDocument50 pagesThe War Against Sleep - The Philosophy of Gurdjieff by Colin Wilson (1980) PDFJosh Didgeridoo0% (1)

- Restrictions on Hunting under Wildlife Protection ActDocument14 pagesRestrictions on Hunting under Wildlife Protection ActDashang DoshiNo ratings yet

- UNIT 4 Lesson 1Document36 pagesUNIT 4 Lesson 1Chaos blackNo ratings yet

- FCP Business Plan Draft Dated April 16Document19 pagesFCP Business Plan Draft Dated April 16api-252010520No ratings yet

- SPY-1 Family Brochure 6-PagerDocument6 pagesSPY-1 Family Brochure 6-Pagerfox40No ratings yet

- When Technology and Humanity CrossDocument26 pagesWhen Technology and Humanity CrossJenelyn EnjambreNo ratings yet

- Arvind Goyal Final ProjectDocument78 pagesArvind Goyal Final ProjectSingh GurpreetNo ratings yet

- The Slave Woman and The Free - The Role of Hagar and Sarah in PaulDocument44 pagesThe Slave Woman and The Free - The Role of Hagar and Sarah in PaulAntonio Marcos SantosNo ratings yet

- Cease and Desist DemandDocument2 pagesCease and Desist DemandJeffrey Lu100% (1)

- FINPLAN Case Study: Safa Dhouha HAMMOU Mohamed Bassam BEN TICHADocument6 pagesFINPLAN Case Study: Safa Dhouha HAMMOU Mohamed Bassam BEN TICHAKhaled HAMMOUNo ratings yet

- Tally Assignment Company CreationDocument1 pageTally Assignment Company CreationkumarbcomcaNo ratings yet

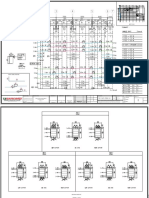

- Revised Y-Axis Beams PDFDocument28 pagesRevised Y-Axis Beams PDFPetreya UdtatNo ratings yet

- BUSINESS ETHICS - Q4 - Mod1 Responsibilities and Accountabilities of EntrepreneursDocument20 pagesBUSINESS ETHICS - Q4 - Mod1 Responsibilities and Accountabilities of EntrepreneursAvos Nn83% (6)

- Authorized Representative For Snap (Food Assistance) and Cash AssistanceDocument1 pageAuthorized Representative For Snap (Food Assistance) and Cash AssistancePaulNo ratings yet