Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mahler and Women - A Newly Discovered Document

Uploaded by

Theo ThorssonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mahler and Women - A Newly Discovered Document

Uploaded by

Theo ThorssonCopyright:

Available Formats

The Musical Quarterly Advance Access published June 24, 2014

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and

Women: A Newly Discovered Document

Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling

To Henry-Louis de La Grange, in gratitude and admiration

It is only a seeming contradiction that my entire earlier life vanished from

me with the writing down of what was heard and experienced. For at that

point I made it my businessand have gone through a strict school in this

doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdu002

1 54

The Musical Quarterly

# The Author 2014. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For permissions,

please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Truly intimate portraits of composers are as invaluable as they are rare.

Occasionally, sources reveal subjects in candid detail, sharing their views

with caring and comprehending contemporaries in whom they placed

their trust. Among all such sources pertaining to Gustav Mahler, none has

proven more informative and significant than the recollections and reflections of Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858 1921), a woman keenly devoted to

the composer, who kept a detailed diary during the roughly ten years of

their deep friendship between 1890 and 1901. An accomplished violinist

and violist who had met Mahler while he was student at the Conservatory,

Bauer-Lechner went on to have a distinguished career as a member of the

Soldat-Roeger String Quartet; she became a close acquaintance of Mahler

and his siblings, often accompanying them on summer holidays. Hundreds

of handwritten pages (many of which are lost or destroyed) document

their encounters and conversations, sometimes preserving Mahlers words

verbatim. Bauer-Lechners journal constitutes a singular achievement,

reflecting a considerable presence of mind about her privileged access to a

man who, she was profoundly convinced, was endowed with uncommon

musical genius.

Fortunately for us, Bauer-Lechner also possessed remarkable attributes

appropriate to the task: an almost obsessive need to write down her

impressions, an objectivity driven by an awareness of history peering over

her shoulder, and, as a professional musician, a considerable capacity to

follow the composers thoughts into the world of inspiration and creativity.

In her 1907 book Fragmente, a collection of observations on a host of

topics ranging from literature to hygiene, from socialism to sexuality,

Bauer-Lechner straightforwardly sets forth her goals as a chronicler:

Page 2 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

regardnot only to leave aside all subjectivity in communication and representation, but also to write down only what was of objective and general

interest that took place in my and anothers purpose in life, that in it

which, if I may call it this, was typical, universally valid and universally

edifying, but once and for all to eliminate and stand aloof from the purely

personal.

. . . It is the preference, but also the duty of a relatively even-tempered,

less passionate disposition that it mirrors the world and humanity more

truly and purely, not contorted and distorted by subjective passion.1

Today I have to write to Natalie Bauer, there is quite a commotion in the

assembly that she could publish her recollections, that would be a catastrophe. Fritz Lohr [a close family friend] has told me that he would be

capable of committing a crime to prevent it. Now, I want to make the suggestion that I go through the things with her and take the occasion to

make clear to her Gustavs position on the publication of such things. We

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Despite the impossibility of such Olympian objectivity (which she

admits), Bauer-Lechners recollections largely avoid superfluous commentary or idle chatter and focus almost exclusively on Mahlers art, his state

of mind when writing music, his reflections on other works and composers, and his frustration with audiences and critics.

Mahler was possibly aware of what Bauer-Lechner was up to, and

perhaps not a little flattered. Her model was Johann Peter Eckermann

(17921854), Goethes amanuensis, who went on to publish his interactions with Mahlers favorite author in Gesprache mit Goethe in den letzten

Jahren seines Lebens (1836). Bauer-Lechner, too, would assemble her

impressions of her famous friend for publication after his passing, although

no book would appear in print until two years after her own death.

Erinnerungen an Gustav Mahler, edited by Johann Killian, the husband of

Bauer-Lechners niece, Friederike, came out in 1923. We know from surviving evidence that this book represents a selection and rearrangement

of passages written in Bauer-Lechners diary and that much of what was

originally recorded is missing from these pages. A later edition of the

Erinnerungen, released in 1984 by Herbert Killian (Johanns son), provides

some additional material, although considerably more remains unpublished.2

Bauer-Lechner was under substantial pressure, especially from

Mahlers wife, Alma, and his sister, Justine, to refrain from publishing intimate details about the life of their cherished husband and brother.

Moreover, virtually everyone else mentioned in the diary was still alive

and potentially uncomfortable about what might be revealed. As Justine

writes to Alma in June 1911, just a few weeks after Mahlers death:

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 3 of 54

have all agreed to bombard her with letters so that this will not come to

pass.3

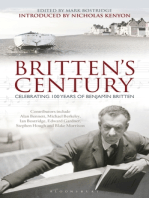

Figure 1. Page 1 of Natalie Bauer-Lechners letter to Hans Riehl. Osterreichische

NB), Vienna: Mus.Hs.44.626. Reproduced by permission.

Nationalbibliothek (O

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

In the event, Bauer-Lechner respected their reservations and published

only a few short segments of her Mahleriana during her lifetime.4

Nevertheless, she was unquestionably planning that an extensive compilation from these memoirs would appear 20 years after my death (if not

earlier?), according to her last will and testament.5 For a number of years,

her partner in this project was Hans Riehl (18911965). Riehl is explicitly

mentioned in this capacity in Bauer-Lechners will, which also refers to

an added supplementary letter about Mahler directed to Hans Riehl, in

his possession.6 This is probably the same document reproduced here,

which is dated Febr. 1917 (fig. 1). Just why Killian, rather than Riehl,

published the abridged 1923 Erinnerungen has yet to be clarified,

although family rights may have prevailed. Still, given Bauer-Lechners

Page 4 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

(and Mahlers) generally liberal and progressive sociopolitical orientation,

it gives one pause to learn that Riehl, who became a leading sociologist in

Austria, later helped found the Neue Galerie in Graz during the Nazi era

and considerably expanded that collection by means of confiscated art.7

Having served as a propagandist for the right-wing Heimwehr in the

1920s, Riehl joined the Nazi Party in 1938.8 It seems a strange twist of

fate that Bauer-Lechner, who in her will thanks providence for the privilege of being intimately acquainted with two Jewish-born geniuses, Gustav

Mahler and Siegfried Lipiner, would entrust her most cherished literary

and personal legacy to a seemingly promising young man who would

plunge headlong into a catastrophe so diametrically opposed to all she

believed in.

Nevertheless, it is thanks to Riehl that, just four years before her

death, Bauer-Lechner penned this sixty-page document, which unquestionably sheds new light on Mahlers personality and private life.9 The

newly discovered letter begins with an apologia, laying out the need for

such biographical information to avoid creating an obvious lacuna in the

knowledge of a great artist (she explicitly cites the open questions surrounding Beethoven in this regard) while expressing obvious discomfort at

revealing intimate details from the life of someone she had known so well.

Rather than incorporating such information into her Mahleriana, which

she had turned over to Riehl in December 1916, Bauer-Lechner found it

best to record what she knew about this delicate topic in the letter,

leaving it to future generations to decide how its content should best be

handled. In our opinion, the time has come for its publication, not for

Sensationslust, but to provide an opportunity for an informed consideration

of its content and implications. A number of important observations

emerge from these pages, observations that will serve to refine our understanding of Mahler as a human being and of Bauer-Lechner as a keen and

not so dispassionate observer of Mahlers life.

As for historical fact, there are not many revelations. Mahlers love

interests have been largely documented or implied in other sources, in

most cases more or less as we find them here. Marion von Weber, Anna

von Mildenburg, Selma Kurz, and others all find mention in more recent

Mahler biographies. What Bauer-Lechners letter brings to the record is a

running narrative that not only corroborates these liaisons firsthand but

also sheds more nuanced light than heretofore available on the emotional

character of Mahler, his reactions to difficult interpersonal situations, his

sometimes fickle nature, even his views on sexuality. She contextualizes

all this within the popular reception of Mahler during his lifetime

and seeks to explain the complex man behind the flirtatious reputation

that circulated among gossipmongers of that time. According to

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 5 of 54

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Bauer-Lechner, Mahler was gripped by a deeply rooted asceticism that

won over his spirit at an early age as a defense against a strongly sensual

nature, all the more, perhaps, because there was in him considerable

inconstancy and unreliability when it came to his procilivities for people.

Further, in keeping with his contradictory nature, it was precisely his

reserved and extremely chaste lifestyle that made him so needy and kept

him in a state of perpetual infatuation.

Two individuals loom larger than all the biographical detail the

letter presents: Justine Mahler and Natalie Bauer-Lechner herself. The

detailed vignettes of Mahlers sister in these pages constitute a unique perspective on the woman who played such a pivotal role in the composers

life before his marriage to Alma Schindler in 1902. It is not a flattering

portrait. Justi, as she is called, emerges as a dragon at the lair keeping all

potential mates at a distance from her beloved brother, thereby exacerbating Mahlers already excitable emotional state and perpetuating an

unnatural, quasi-incestual union between brother and sister. BauerLechner makes no secret of her opposition to this arrangement. On the

one hand, her views of love and marriage embraced an ideology regarded

as rather progressive at that time. Estranged, then divorced from her

husband after a disastrous marriage begun at the age of seventeen, BauerLechner never returned to matrimony, espousing instead a somewhat

idealistic view of love and lovemaking considered by many scandalous in

its day. She openly refers to higher forces operating above human morality,

attributing the inspiration for this perspective to a long-term relationship

with Siegfried Lipiner. Lipiner, for his part, seemed equally open-minded:

his first wife went on to marry Albert Spiegler; Lipiners second wife was

Spieglers sister (during which marriage his liaison with Anna von

Mildenburg was an open secret). From the content of this letter, it seems

they all remained great friends.

The second motivation for Natalies railing against Justines obstructionism was her own infatuation with Mahler. This attachment to my

Gustav, as she occasionally calls him here, is also apparent in the

Recollections when at times her enthusiasm exceeds professional respect,

friendly admiration, or even outright awe. Certain loving details that she

presents make it difficult not to sense an emotional involvement with her

subject. But what one might merely suspect in reading the heretofore published sources is explicitly revealed in this letter: her romantic interaction

with Mahler, the one aspect of their relationship that she deliberately suppressed elsewhere. The details of this liaison may surprise many readers,

and it raises questions about the composer and how we have come to

understand him through her eyes.

Page 6 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

But I certainly confess to you that Natalies coming is absolutely abhorrent

to me. Apart from the matter in question (or perhaps precisely because of it),

I detest the constant mothering, browbeating, inspecting, and spying. I

wouldnt take it this year.10

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

The level of detail (which can often be corroborated by other

sources), and the candor and immediacy that fill the pages of the

Recollections have convinced almost all Mahler experts of the veracity of

Bauer-Lechners account. Indeed, the break in their relationship in 1901

has often been bemoaned by chroniclers of Mahlers life as a significant loss

to the historical record, for after that point we no longer have a running

account of such revealing conversations in the composers life. BauerLechner herself poignantly anticipates this in the last episode of the letter

to Riehl. But does the nature of their relationship, as it has now been

revealed, compromise Bauer-Lechners credibility? Does their intimacy call

into question the trustworthiness of her testimony? If so, it would be a

major blow to the long line of Mahler scholars, including the present

writers, who have come to accept her accounts as essentially reliable.

This letter is not without factual errors; in 1917, Bauer-Lechner was

not yet sixty, but the years of the Great War had been difficult, and at

times her memory appears to fail her. Thus, for example, Leander is not

the poet of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Mahlers dry spell ending

around 1892 did not last ten years, and Marie Renard did not sing

Puccinis La Bohe`me at the Hofoper under Mahler. Then there are interpretive questions. Was Mahlers depressed state during Bauer-Lechners

visit to Budapest in 1890 entirely attributable to the failed love affair with

Marion von Weber two and one-half years earlier, as she claims? In the

context of explaining this, Bauer-Lechner makes no mention of the

deaths of Mahlers sister Leopoldine and both of his parents the previous

year, the difficulties he was having in organizing family life for the surviving siblings, or his troubles with the management at the Budapest Opera.

She also seems to accept as fact that Mahler and Anna von Mildenburg

never consummated their relationship, completely suppressing the likelihood that Mildenburg simply denied something she did not want posterity

to know about.

Bauer-Lechners account seems weakest, however, when she tries to

explain her own fate in the course of Mahlers life. Putting the onus on

Justines pathological jealousy may have enabled her to preserve the illusion that her great love had been thwarted by external circumstance and

the petty interference of his sisters uncomprehending small-mindedness.

But how did she come to terms with all the evidence that suggested otherwise? Here Mahler writes to Justine in preparing for the summer vacation

at Steinbach am Attersee in 1894:

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 7 of 54

I go walking diligently. . . . Alone and with Natalie. . . . That people

gossip about it, as they talk about everything, is immaterial to me. One

cannot avoid it; after all, its better than if it were [Rita] Michalek or

[Selma] Kurz.12

Given what we now know, confusion about the status of their relationship

can no longer be attributed solely to Bauer-Lechners wishful thinking.

Ultimately, it must be left to the reader to assess how BauerLechners inner emotions, personal agenda, and self-conception as an eyewitness may have biased her view of Mahler. Yet one point seems worth

mentioning. Despite the disparity in their feelings for each other and

whatever disappointment this may have caused, Bauer-Lechner persisted

in her account with unwavering devotion, seeing her emotional investment as subordinate to the historical project she had taken upon herself;

she maintained her chronicle up through the first Viennese performance

of Mahlers Fourth Symphony on 12 January 1902, even though she knew

he had been engaged to Alma for several weeks. As Bauer-Lechner so

poetically writes to Riehl, the result traces the story of Mahlers genius

and, sprinkled in there, the quiet deeds of my happiness in sacrificial

love. She could not remove herself from the story she told, but the deep

involvement that surfaces here makes her accomplishment all the more

noteworthy. We can continue to remain grateful for Bauer-Lechners

sense of duty to bear honest testimony, even if she could never completely succeed.

Editors Note: Although the manuscript is in good condition, BauerLechners habit of revising and re-revising has left certain passages difficult

to decipher. For the present edition, a diplomatic rendering of insertions

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

That these sentiments did not remain hidden from Bauer-Lechner seems

clear, as indicated in the following remarks Mahler wrote to Justine in

early September 1901: Its starting again with Natalie. It hurts me

terribly, but now I must tell her the unvarnished truth and, of course,

shatter her. But I hope shell soon be helped back on her feet again.11

Interestingly, this is the last mention of Natalie in the family letters.

Mahler was to meet Alma a few weeks later at the salon of Bertha

Zuckerkandl, but the break seems to have preceded this event and was no

doubt precipitated by Bauer-Lechners euphoric hope in the wake of the

lovemaking episode at Worthersee just a few weeks earlier.

In fairness to Bauer-Lechner, Mahler was clearly capable of enjoying

her company and valued their friendship. Just days prior to the letter cited

above, Mahler writes to his sister defending Natalie in the face of criticism

behind her back, and continues:

Page 8 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

and crossings-out has been put aside in favor of what seems to be the

latest layer of text. The only exception to this is a handful of marginal

notes that the author inserted by way of her own cues; these are rendered

with a caret ( ) at the beginning and end of the passages in question. The

authors original German orthography, which includes such idiosyncracies

as andern (for anderen), has been preserved throughout, except for

the abbreviations m

and n

, which have been rendered as mm and

nn. Bauer-Lechner also included some footnotes, which appear at the

bottom of their respective pages; the manuscripts page numbers are given

in square brackets. Bauer-Lechner numbered page 57 twice, apparently as

a result of substituting two pages for the original 57; these are indicated

here as 57/1 and 57/2, respectively. Editorial annotations appear as

endnotes.

Morten Solviks research focuses on the tantalizing connections between music and

culture, especially with regard to Gustav Mahler and the turn of the century. Essays on

Mahler have appeared in The Mahler Companion (2002), Perspectives on Gustav Mahler

(2005), and the Cambridge Companion to Mahler (2007). He has contributed to several

recent television documentaries on Mahler and is the co-editor of Mahler im Kontext/

Contextualizing Mahler (2011). A member of the Board of the International Gustav

Mahler Society and the Editorial Board of the Critical Edition of Gustav Mahlers works,

Solvik serves as the Center Director of IES Abroad Vienna where he also teaches music

history. E-mail: msolvik@iesvienna.org

Stephen E. Hefling, Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve University, is the codirector of Gustav Mahler: Neue Kritische Gesamtausgabe, for which he recently revised

Mahlers autograph piano version of Das Lied von der Erde (2012). He also serves on the

board of the International Gustav Mahler Society in Vienna. Hefling is the author of

Gustav Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde (2000), editor of Mahler Studies (1997), and has published over twenty-five articles and book chapters on the life and works of Gustav Mahler.

E-mail: seh7@case.edu

1. Bauer-Lechner, Fragmente: Gelerntes und Gelebtes (Vienna: Rudolf Lechner & Sohn,

1907), 16 and 107.

2. The present authors, along with Thomas Hampson, are currently engaged in a

project to gather and present in print Natalies recollections, Mahleriana, to the fullest

extent possible. The current English version, Recollections of Gustav Mahler, trans. Dika

Newlin, ed. Peter Franklin (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980), is largely

based on the German edition of 1923.

3. Justine Rose to Alma Mahler, 8 June 1911, quoted in Andreas Michalek, Justine

Rose: Drei Briefe an Alma Mahler-Werfel, Nachrichten zur Mahler-Forschung 56

(Autumn 2007): 4142; English trans. in News About Mahler Research 56 (Winter 2008):

4041.

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Notes

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 9 of 54

4. Excerpts from her diaries appeared anonymously in Der Merker 3, no. 5 (1912):

184 88, and under her name in Musikblatter des Anbruch 2, nos. 78 (1920): 3069.

5. Typescript copy, n.d., at the Mediathe`que Musicale Mahler, Paris: Die

Erinnerungen an Gustav Mahler . . . sind . . . 20 Jahre nach meinem Tod herauszugeben.

(wenn nicht fruher?).

6. [. . .] ein nachgetragener und erganzender Brief uber Mahler, an Hans Riehl

gerichtet, in dessen Besitz.

7. See Karin Leitner-Ruhe et al., eds., Restitution (Graz: Universalmuseum Joanneum,

2010), 1718, 92 93, 135 40, passim.

8. See Biographie Hans Riehl, Archiv fur die Geschichte der Soziologie in

sterreich, http://agso.uni-graz.at/bestand/11_agsoe/index.htm.

O

10. Letter of 6 May 1894, in The Mahler Family Letters, ed., trans., and annotated by

Stephen McClatchie (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 279; German edition:

Gustav Mahler: Liebste Justi! Briefe an die Familie, ed. Stephen McClatchie, redacted by

Helmut Brenner (Bonn: Weidle Verlag, 2006), 388.

11. Mahler to Justine, Family Letters, 359; Briefe, 490.

12. Mahler to Justine, 3 September 1901, Family Letters, 350; Briefe, 477 78.

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

9. Recent acquisition of the Music Collection of the Austrian National Library,

Mus.Hs.44.626, from a previous private owner.

Page 10 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

Wie ich durch Albine Adler erfuhr, soll Mahlers erste Liebe, zur Tochter des IglauerPostmeisters, eine auerst lebendige & innige gewesen sein.* Sie spielte sich in den

heimischen Ferien zur Wiener-Konservatoriumszeit ab. [3] Ich erinnere mich nur,

da mir Gustav einmal von dem Verhaltnis zu einem Iglauer-Madchen sagtewas

llung

sich wahrscheinlich darauf bezog: ,,Und solche gesunde Lebensfreude & -Erfu

hren,

war nur dazu da, dem jungen Menschen die notwendige Nahrung zuzufu

welche er zur kraftigen Entwicklung seines Korpers & Geistes brauchte.

Von seinem spatern Lieben tat mir Mahler die erste Erwahnung aus Kael,

als er am Hoftheater daselbst Kapellmeister war. Und hier hatten es ihm gleich

zwei Sangerinnen aufs Heftigste angetan. Die Eine schwarz, die Andre blond

(so glaub ich erzahlte er mir), die Eine sanft, die Andre bewegt & erregt, stellten

sie die volligste Gegensatzlichkeit dar. Wie leidenschaftlich ihn diese [4]

Neigungen ergriffen, bezeugen mehrere aus den ,,Liedern eines fahrenden

Gesellen, wo auch das Wort, unter dem Pseudonym Leander, von ihm ist. ,,Die 2

*

Albine Adler, die intimste Jugendfreundin Justi Mahlers, war dem Mahlerschen Hause treuest

nn

anhanglich. Doch stand sie vollig im Bann Justinens, mit der sie, ohne Wahl durch dick & du

ging. Erst nach Mahlers Tod schwang sich Albi zu einiger Selbstandigkeit auf.

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

[Page 1]

ber Mahlers Lieben an Hans Riehl von Natalie Bauer-Lechner)

(Brief u

Febr. 1917.

Mein liebster Hans!

nschtest, ich sollte als Erganzung zu meinen Mahler-Erinnerungen, auch

Du wu

ber sein Lieben zu Frauen bekannt ist; da Du der

das schriftlich mitteilen, was mir u

rfe diese bedeutsamste Seite des menschlichen

gewi richtigen Meinung bist, man du

Lebens nicht ausschlieen. Auch wiesest Du darauf hin, welche Unklarheit, ja

Verwirrung in die Aufzeichnungen von Beethovens Lebensgang die groe

Unkenntnis, der ihm leidenschaftlich geliebten Frauen, gebracht habe.Mich hinwiderum hielt Empfindung & Erwagung von solchen Mitteilungen ab, da

Personlichstes nicht vor fremde Ohren gehore, & es hatte mir wie Verrat geschienen,

das was ich aus Mahlers Mund, oder durch eigenes Miterleben & Beteiligtsein hierber wute, in meinen Erinnerungen [2] Preis zu geben. Doch da kam mir der

u

test: Ich wollte Dir in Briefform

Gedanke eines Auswegs, den Du freudig begru

schreiben, was ich Bedenken getragen meinem Werk einzuverleiben; & Du solltest

wenn Du auch die vervollstandigenden Dokumente in Worten & Briefen gesammelt,

ck-weisesden Gebrauch von diesen

denn mein Wissen ist nur ein Bruchstu

Mitteilungen machen, welcher Dir, & andern berufenen Nachlebenden, wichtig &

richtig erschiene.

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 11 of 54

As I found out from Albine Adler,2 Mahlers first lovefor the daughter of the Iglau

postmaster3was apparently very vibrant and deeply felt.* This took its course

during his vacations at home while attending the Vienna Conservatory.4 [3] I only

remember that Gustav once told me about a relationship with a girl from Iglau, which

probably referred to this, saying: And such healthy love of life and fulfillment was

only there in order to provide the young man with the necessary nourishment that he

needed for the firm development of his body and mind.

Of his later loves, the first Mahler mentioned was one from Kassel, while he was

a conductor at the Court Theater there.5 And here he had seriously fallen for two

singers at once: one with black hair, the other blond (I think he told me); the one

gentle, the other excitable and excitedconstituting absolute opposites of each

other. How passionately these [4] affections seized him is testified by several of the

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, where the text stems from him under the pseudonym

of Leander.6 These include Die 2 blauen Augen von meinem Schatz [The two blue

Albine Adler, Justi Mahlers closest girlhood friend, was most devoted to the Mahler household, yet

she was fully under the spell of Justine, whom she loyally and blindly followed through thick and thin.

Only after Mahlers death was Albi able to achieve a certain degree of independence.

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

[Page 1]

(Letter about Mahlers Loves to Hans Riehl by Natalie Bauer-Lechner)

Feb. 1917.

My dearest Hans!1

You requested that as a supplement to my recollections of Mahler I should also

report in writing what I know about his love of women, since you are of the assuredly

correct opinion that one may not exclude this most significant side of human life. You

also pointed out the lack of clarity, indeed confusion, that the vast ignorance about the

women passionately loved by Beethoven has brought into the accounts of his life. On

the other hand, feeling and reflection held me back from making such revelations since

that which is most personal should not reach strangers ears, and it would have seemed

to me like betrayal to divulge in my recollections what I knew about this from Mahlers

lips or my own experience and participation. [2] But then there came to me the idea of

a way out, which you happily welcomed: I would write to you in the form of a letter

that which I had misgivings about incorporating into my work, andonce you had

collected the complete documents in words and letters, for my knowledge is only

fragmentaryyou would make use of this information in a manner that you and others

so appointed in future generations find relevant and appropriate.

Page 12 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

,,Ging heut Morgen ubers Feld,

Ist das eine schone Welt. . . .

das ihm von den seligen Lippen stromte.*

Nicht viel mehr als an die Tatsache erinnere ich mich leider, der jedenfalls viel

bedeutungsvolleren Liebe Mahlers zu einem jungen Wesen (ich wei nicht,

warum mir immer vorschwebt, einer [6] Forsterstochter?) mit dem es, von Prag

hrte. Der Name der Braut, gleichwie die

oder Leipzig aus (?) sogar zur Verlobung fu

rften ja nicht schwer zu ermitteln sein, da die

nahern Umstande dieses Bundes, du

Betreffende wol noch lebt & sicher auch im Besitz von Mahlers Briefen ist.** Ich

wei nur, da er mir eigentlich erst aus der Zeit, als es mit dieser Liebe schon vorbei

war, davon berichtete: Er hatte Frau Weber in Leipzig seine Besorgnis &

ber das zu erfu

llende Verlobnis geklagt, die ihm aufs Lebhafteste

Unsicherheit u

rs Leben zu binden. Und Gustav folgte nur

abriet, sich unter solchen Umstanden fu

zu gerne dieser Weisung. Zur Strafe aber legte er sichs auf, nicht schriftlich, sondern

durch sein eigenes Wort die Verlobung zu losen, womit er dem Madchen, das ihn

gt. Doch heiratete sie spater einen

herzlich liebte, gewi noch Schwereres zugefu

Andern; hat aber [7] zum Beweis alter Anhanglichkeit, spater Mahler (in Pest?)

nocheinmal besucht.

llung ihm Jahre

Mahlers tiefste & innigste Liebe (aus deren Nichterfu

tiefsten Leids erwachsen) ging ihm in Leipzig auf: In der Gattin des Enkels Karls

*

( & das sich nachher aus dem Lied zum herrlichen Thema seiner I. Symphonie erweiterte).

(Oder ware sie gar identisch mit der Iglauer-Postmeisterstochter? Und Gustav hatte, nur aus

Discretion gegen sie, eine ,,Forsterstochter draus gemacht?)

**

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

hend Meer in meiner

blauen Augen von meinem Schatz &: ,,Ich hab ein glu

tterndsten Tonen rast, gehoren

Brust, worin die Eifersucht in den wildsten, erschu

dazu. Auch hat er zwei unkomponierte Texte aus jener Zeit (:,,Es starrt die Sphinx

mit schwarzen Ratselaugen, beginnt das eine), die seine Leidenschaft zum

Gegenstand haben, mir spater in Hamburg geschenkt; sie sind in meinen

Mahlererinnerungen erhalten. Auer zu Begeisterung & Herzensqualen scheint

aber diese Doppelneigung zu Nichts gefuhrt zu haben. Zum Schlusagte mir

Gustavhab ihm die Eine seiner Flammen gestanden: Er hatte bei ihr mehr [5]

ck gehabt, wenn er sie allein & nicht auch die Andre ins Herz geschloen

Glu

rde!

haben wu

Von der ,,Leidenschaft, die Leiden schafft, in die er doppelt tief verstrickt

hlingsmorgens, als er im leuchtenden Sonnenschein

gewesen, geno er aber eines Fru

henden Au sich erging, & im Entzu

cken u

ber die ihm so hei geliebte

in der blu

ckt, den Freuden der

Natur, wie mit einem Zauberschlag sich allen Schmerzen entru

hlte. Und hinreiender konnt es nicht zum

Schopfung aber wiedergeschenkt fu

Ausdruck gebracht sein, als in dem jubelnden Lenzeslied:

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 13 of 54

Went out this morning over the field

Isnt it a beautiful world. . . .

that flowed from his blessed lips.*,8

Unfortunately, I do not remember much more than simply the fact of a love far more

important to Mahler for a young creature from Prague or Leipzig (?) (I do not know

why I keep thinking it was the [6] daughter of a forest warden?) with whom the

matter even led to an engagement.9 The name of the bride-to-be as well as the

further particulars of this bond ought not be difficult to uncover, since the person in

question is probably still alive and also certainly in possession of Mahlers letters.** I

only know that he told me, at a time when this love was long over, that he had complained to Frau Weber10 in Leipzig about his worries and insecurity about fulfilling

the engagement, and that she had most emphatically advised him against committing

himself for a lifetime under such circumstances. Gustav was only too happy to follow

this advice. As punishment, however, he took it upon himself to break the engagement in person rather than in writing, thereby inflicting more pain on the girl, who

loved him very much. She later married someone else but [7] subsequently visited

Mahler one more time (in Pest?)11 as a sign of her former attachment.

Mahlers deepest and most heartfelt love (which in its nonfulfillment caused

him years of pain) befell him in Leipzig: the wife of the grandson of Carl

(and that later expanded from the song into the magnificent theme of his First Symphony).

(Or is she perhaps identical with the postmasters daughter in Iglau, and Gustav was simply

turning her into the forest wardens daughter for the sake of discretion?)

**

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

hend Messer in meiner Brust [I have a

eyes of my beloved] and Ich hab ein glu

glowing knife in my chest], in which jealousy rages in the wildest, most jarring tones.

There are also two texts from this time that he did not set to music (one begins: Es

starrt die Sphinx mit schwarzen Ratselaugen [The Sphinx stares with black riddling

eyes], which were inspired by his ardor and which he later gave to me as a present in

Hamburg; they are included in my Mahler recollections.7 Other than rapture and

heartache, it seems this double infatuation led to nothing. In the end, my Gustav

said, one of his flames admitted that he would have had more [5] luck with her if he

had taken only her and not also the other into his heart!

But in the passion that provokes suffering [Leidenschaft, die Leiden schafft]

which entangled him twice over he also found that, one spring morning as he walked

across the blooming meadow in radiant sunshine, delighting in the nature he loved so

deeply, as if by a stroke of magic all the pain disappeared, and he felt blessed again in

the joys of creation. And this could not be expressed more enchantingly than in the

joyous song of spring:

Page 14 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

Siehe meine Mahlererinnerungen Bnd. 29.

(ich glaube dies war der Name ? der unter ihrem Bildnis stand, das ich durch Jahre auf

Mahlers Schreibtisch sah).

**

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

rdig-ernste, hochkultivierte & ungemein

Maria von Weber.Sie war eine liebenswu

musikalische Frau, zu der sich Gustav durch Geistes & Seelenbanden hingezogen

hlteerst ahnungslos, bis zum Erwachen des leidenschaftlichsten Bewusstseins &

fu

hrt wurden sie im auern Brennpunkt der Musik. Den

Verlangens.Zusammengefu

herrlichen Leistungen Mahlers kam sie, selbst eine treffliche Pianistin, im hochsten

Sinn entgegen. Innerlich fand er sich der um 9 Jahre altern, lebensgewandten holden

tterlichem Sorgen seine Bedu

rfnisse ersah &

Frau, die in weiblich-warmem [8] fast mu

llte, gleich herzlich zugenahert. Ungemein wohl fu

hlte er sich in ihrem durch 3

erfu

ndchen) heiter belebten Hause. Den Kleinen, deren

anmutige Kinder (& einem Hu

jedes Einzelne hei an ihm hing, komponierte er einen Kreis von Liedern: ,,Um

schlimme Kinder artig zu machen. Mit Weber verbanden ihn die Skizzen Carl Marias

rdig ausfu

hrte, wahrend Ersterer den

zu den ,,3 Pintos, welche Gustav bewundernswu

Text erganztesofern ihn nicht Gustav selbst, ohne viel zu fragen, seinen eigenen

rfnisen & dichterischen Wu

nschen anpate. Damals entstand

musikalischen Bedu

r mich ein

auch Mahlers I. Symphonie: ,,Denn zu jener Zeit hatte die Welt fu

Lochwie ers, noch nach so vielen Jahren, mir in freudiger Erinnerung nannte:*

,,Ich war vor Begeisterung & Beseeligung in die hochsten Himmel getragen, lie meine

ckte

Schaffenskraft [9] ins Unendliche wachsen. Sein Werk fand verstehende, entzu

ckweis zu den Freunden trug & es

Aufnahme, als er es, noch na von der Feder, stu

gel aus der Taufe

unter deren Beistand, wo seine 2 Hande nicht ausreichten, am Flu

gehoben ward. So flohen ihnen die Abende, welche Mahler nicht zu dirigieren hatte,

mit seiner eigensten Kunst dahin. Oder Marion** & er verloren sich in unerschopflichem Geplauder, wenn Weber sie, wie fast immer, allein lie. Es mute das seiner Frau

den Verdacht erwecken, als ob es absichtsvoll geschahe, wenn er Mahler stets ermunterte, ihr wahrend seiner Abwesenheit Gesellschaft zu leisten: Als wolle er sie schadlos

halten, ja beide geflientlich einander nahe bringen, zum Gegengewicht einer Liaison,

die er mit einer Schauspielerin (glaube ich sagte mir Gustav) hatte, welche ihm Zeit &

Interee gefangen nahm. [10] Was beideGustav & Marionaber verlor, oder eigentlicher, sie dem seeligst-unseeligen Lieben gewann, war Tristan, welchen sie einst zu

vier Handen spielten. Da sie, wie durch die Macht des Zaubertrankes, blitzartig das

` legevammo (suoniamo)

berfiel. ,,Quell giorno non piu

Wien um ihr innigst-Einssein u

avanti, auch sie erlebten es& glaubten sich dem Gestandnis ihrer Liebe, der

cks, umso vertrauender hingeben zu du

rfen,

stralend [sic] aufgehenden Sonne ihres Glu

nschtes geschah.Aber wie

als auch Weber damit nichts Boses, ja vielleicht nur Erwu

anders sollte es kommen als sie wahnten & hofften! Mahler, deen Geist, in seiner

Ehrlichkeit & Offenheit, ihr Bund, ohne das Mitwien des Gatten, belastete, drangte,

da sie sich ihm entdeckten. Zwar fiel es ihnen unendlich schwer, aus dem heilig-

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 15 of 54

See my Mahler recollections, vol. 29. [NBL2, 172 76; abridged version in NBLE, 157 61.]

I believe that was the name? that stood under the picture I saw for years on Mahlers desk.

**

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Maria von Weber.12 She was an agreeably earnest, highly cultured, and unusually

musical woman whose mind and soul Gustav felt drawn to, at first unconsciously, and

then through the awakening of the most passionate awareness and desire. They were

brought together through their shared passion for music. Herself an excellent pianist,

she was able to live up to Mahlers superb achievements on the highest level.

Inwardly, he immediately felt deeply tied to this woman, nine years his senior,13 experienced and graceful, who recognized and fulfilled his needs with warm, feminine, [8]

almost motherly care. He felt uncommonly comfortable in her home, which was animated in lively fashion by three sweet children (and a little dog). For the little ones,

every one of whom was warmly attached to him, he composed a cycle [Kreis] of

songs: Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen [To make naughty children nice].14

His connection to [Herr] Weber lay in the sketches to Carl Marias 3 Pintos, which

Gustav completed in admirable fashion,15 while Weber supplemented the textat

least to the extent that Gustav himself didnt adapt it to his own musical needs and

poetic wishes without really asking. Mahlers First Symphony also came into being at

this time:16 For at that time the world had a hole [Loch] for me,17 as he told me in

joyful recollection many years later.* I was carried to the highest heavens through

ardor and spiritual fulfillment, let my creative powers [9] expand into the infinite. His

work was met with understanding and delight when he presented parts of it, still wet

with ink, to his friends, and when it was premiered at the piano, occasionally with their

help when his two hands did not suffice. Thus the evenings when he did not have to

conduct18 flew by with Mahlers most unique creations, or Marion** and he would get

lost in inexhaustible conversation when Weber left them alone, as he almost always

did. By constantly encouraging Mahler to provide her with company when he was

away, it must have awakened in his wife the suspicion that this was happening on

purpose, as though he wanted to exonerate them, yes even intentionally bring them

closer to one another, as compensation for a liaison he was having with an actress (I

believe Gustav told me), which was taking up his time and interest. [10] But what lost

them bothGustav and Marionor rather what captured them in most blissful illfated love, was Tristan, which they used to play four hands. As if through the power of

a magic potion, they were suddenly overcome by the knowledge of their most intimate

` legevammo (suoniamo) avanti.19 They, too, experioneness: Quell giorno non piu

enced this and believed they could give in to confessing their lovethe shining rising

sun of their happinessall the more confidently since they meant Weber no harm,

and it was perhaps even something he wanted. But how differently it was to turn out

from what they wrongly believed and hoped! Mahler, whose spirit in its honesty and

openness was burdened by their bond without the joint knowledge of the husband,

insisted that they reveal themselves to him. To be sure, it was unendingly difficult

Page 16 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

hlens, das ja stets nur den Liebenden allein

[11] verborgenen Dunkel ihres Fu

angehort, &in Wahrheit nur sie angehtheraus ans grelle Tageslicht zu treten;

aber eben in dem sichern Glauben, da sie bei Weber, aus seinem eigenen

rden, teilten sie ihm eines Tages ihr

Verhaltnis, Verstehen & Mitgehen finden wu

berraschung & Enttauschung, als

Geheimnis mit. Doch wie furchtbar war ihre U

Weber, der nichts geahnt & bemerkt haben wollte, statt Billigung & Einvernehmen,

den gemeinen, kleinen Ehr- & Rechtstandpunkt herauskehrte; ja Gustav glaubte

hren, welchen er, der principiell

schon, es werde zu einer Forderung von Jenem fu

ber,

der grote Gegener des Duells war, dem Offizier & Gatten der Geliebten gegenu

rde ausweichen konnen. Doch kam es zu diesem unmenschlichsten aller

nicht wu

,,Ausgleiche, Gott Lob, nicht. Weber sagte, er wolle sich die Liebe seiner Frau [12]

ckgewinnen. Von der den Liebenden so erhofften Losung im wahren Sinne

zuru

low, Wagner & Cosima fahig

deren freilich nur allerhochste Menschen, etwa wie Bu

sindwelchen Ethik & Gottgebot fordern, da die Liebenden vereinigt, die

Nichtliebenden aber getrennt werdendavon war bei Weber keine Rede.Mahler,

der das Webersche Haus nicht mehr betreten konnte, nach des Mannes vollig

feindseligem Verhalten, nahm seinen Abschied von Leipzig; wol in der Hoffnung,

rde, die er in der Abschiedsstunde

da er von der Geliebten nicht getrennt bleiben wu

beschwor, ihm nachzufolgen:Er harrte ihrer am Starhembergersee, um sich

dauernd mit ihr zu verbinden. Aber Marion kam nicht! Bei dem zartesten Gewien,

ber sich, [13] ihr Glu

ck auf dem Unglu

ck

welches in ihr wohnte, brachte sies nicht u

berlaen hatte!

der verlaenen Kinder aufzubauen, die ihr Weber nimmermehr u

So erwartete sie Gustav mit qualvoller Unruhe & Sehnsucht ins Vergebene. Denn

nicht einmal Nachricht durfte ihm Marion geben, die sich gegen Weber hatte eidlich

en, Mahler nicht zu schreiben! Wie aber alle solche tyrannischen,

verpflichten mu

jedem wahren Recht & Lieben Hohn sprechenden Gewaltmaregeln, stets einen

Ausweg findenweil das hohere, gottliche Recht, gegen die starre Menschensatzung,

doch zum Durchbruch kommt,so fand sich auch hier in der Folge ein Mittel des

r die Liebenden: Eine Freundin Marions, Frau

wenigstens schriftlichen Austausches fu

bernahm es, dieauerlich an sie geFiedler (die spatere Gattin Hermann Levys) u

richteten Briefe Beiderzwischen ihnen zu vermitteln. ,,Und nun begann erst unser

[14] wahres Liebesleben, sagte mir Gustav spater davon. Die durch die Verhaltnise

[sic] grausam Getrennten, lebten sich in zahllosen, nicht endenden Schreiben aus, die

stets recommandirt, & vor Ungeduld gewohnlich auch Expre, von Einem zum

Andern hin & her flogen.Gustavs Schwester Justi, welche als sie nach Pest kam, aus

Neugierde, Anteil & Eifersucht, heimlich die Briefe Marions an Gustav las (denn

Discretion & Verlalichkeit in solchen Dingen war nicht ihre Sache) erzahlte mir

ber: Frau Weber mu

e von Fru

h bis Nacht daran geschrieben haben, sonst

spater daru

ware ihre Lange unerklarlich gewesen; & von der Glut ihres Inhalts mache man sich

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 17 of 54

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

[11] to step forth into glaring daylight from the sacredly clandestine darkness of their

feeling20which indeed at all times belongs only to lovers and in truth only concerns

thembut precisely in the certain belief that they would find understanding and

cooperation from Weber, given his own affair, they one day finally shared their secret

with him. Yet how terrible was their surprise and disappointment when Weber, who

claimed to have suspected or noticed nothing, reacted not with approval or understanding, but instead flaunted the commonplace, petty arguments of honor and

justice. Gustav even believed it would result in a challenge to a duel, which he, on

principle an outspoken opponent of duels, would not be able to avoid vis `a vis an

officer and the husband of his beloved.21 It did not, however, thank God, come to

this most inhuman of all compromises [Ausgleiche].22 Weber said he wanted to win

back the love of his wife. [12] Regarding the solution so hoped for by the lovers in

low, Wagner, and Cosima

the truest sense, of which only the highest people like Bu

are capable,23 and which ethics and Gods commandment demand: [i.e.] that lovers

be united and those not in love be separatedthis was out of the question for

Weber. Mahler, who could no longer enter the Weber household after the husbands

utterly hostile behavior, took his leave of Leipzig, in high hopes that he would not

remain separated from his beloved, whom in their moment of parting he implored to

follow him. He waited for her at Lake Starhemberg,24 hoping to reunite with her for

good. But Marion did not come! Owing to the utterly tender conscience that dwelt

within her, she could not bring herself [13] to build her happiness on the misfortune

of her abandoned children, whom Weber would never have relinquished to her!

Thus Gustav waited for her in painful agitation and expectation, yet to no avail.

Marion was not even allowed to send him news of herself; she had to promise Weber

under oath that she would not write to Mahler! But as a way is always found around

all such ty-rannical acts of force, which are antithetical to all that is just and loving

because higher, godly justice nevertheless prevails against the hollow rules of humanity after allso, too, a way was eventually found that at least allowed written

exchange between the lovers: a friend of Marions, Frau Fiedler (later the wife of

Hermann Levy),25 took it upon herself to relay the letterswhich were addressed on

the outside to herbetween them. And only now did our [14] real love life begin,

Gustav later told me about the matter. The two of them, separated in such a brutal

manner, gave themselves free rein in innumerable, unending missives that flew back

and forth from one to the other, always sent by registered mail and, owing to their

impatience, usually also express. Gustavs sister Justi,26 who, out of curiosity, compassion, interest, and jealousy, secretly read Marions letters to Gustav after arriving in

Pest (she was never one for discretion and trustworthiness in such matters), later told

me that Frau Weber must have written from morning till night, otherwise the length

of them would be inexplicable, and one could not imagine the fervency of their

Page 18 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

rchte, da diese, gewi ergreifendsten, Dokumente einer bedeutenden, liebendsten

Ich fu

Frauenseele, nicht mehr sind. (Mahlers Briefe hat Fr. Weber hoffentlich treu bewahrt!) Aber ich

wei, da Justi, die gleich jedem Mahler zu nachst stehenden Menschen, den groten Einflu auf

ihn hatteden sie keineswegs immer zum Besten gebrauchtein ihrer Eifersucht auf alle Frauen,

nicht nur, die Gustav etwas waren, sondern auch auf selbst jedes Zeichen (Briefe & Erinnerungen)

von Diesenes in Wien einst von ihm erreichte, da sie ein Autotafe [sic] unter seinen Briefen [15]

anstellen durfte. Darunter werden wol auch die von Marion gewesen sein! Und, um es gleich hier

vorgreifend zu erwahnen: Unzahlige von meinen Briefen an Gustav (auer den wenigen, die ich

selbst bewahre) gingen damals in Flammen auf. Dagegen besitze ich von Mahler fast keine

Schreiben: Da ich ihm, der so gern Briefe erhielt, als er sie ungern schrieb, hierin gern nachgab;

umsomehr als wir ja 10 Jahre lang zum Hauftigsten & Intensivsten miteinander verkehrten, wobei er

ndlichen Austausch u

ber Alles & Jedes sich einem anvertraute, wie ichs bei Keinem mehr,

im mu

her noch spater, getroffen habe. Und das gehorte zu den liebsten Seiten seines personlich

weder fru

rftigen, treuherzigen Wesens.

bedu

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

keinen Begriff!* [15] Aber auch diese grote Liebe Mahlers erschopfte sich endlich an

ihrer Hoffnungslosigkeit.

Als wirdie Wienerfreundekurz nachdem Gustav Leipzig & den

chtig bei uns wieder sahen, waren wir erschreckt

Starhembergersee verlaen, ihn flu

ber sein schlechtes Aussehen & die unruhig-tiefgedru

ckte Stimmungwelche sich

u

auch darin auerte, da er meinte, er werde nie mehr eine Stellung bekommen! Etwa

zwei Jahre spater, als er Direktor der Pesteroper war & ich ihn daselbst besuchte (:

Du erinnerst Dich daran aus meinen Mahler-Erinnerungen?) hatte er sein

Gleichgewicht wieder gewonnen; aber ich fand ihn doch, so sehr er sich meines

Kommens damals freute, wie belastet von schweren Erinnerungen & im traurigen

hl seiner Einsamkeit. Auch beru

hrte er, [16] trotz seiner groen Mitteilsamkeit

Gefu

gegen mich, mit keinem Worte, was ihm noch zu schwer auf dem Herzen lag; & erst

ttete er mir seine Seele in vielen, vielen Erzahlungen

spater in Berchtesgaden schu

ber aus. Was aber zum starksten Beweis seines tiefsten Mitgenommenseins von

daru

dem Leipziger-Lieben & -Leiden diente, war, da er seit jenen Tagen, zehn Jahre

lang, nichts Groeres komponierte.

In Pest konnte, im Umgang mit seinem Opernpersonal, ein personliches

Annehmen & Annahern ihm nicht ausbleiben. Und wie immer waren es vor Allen

die Frauen, welche Mahlers Stellung, aber besonders auch sein von ihnen eher

erkanntes & lebhaft bewundertes Genie, an ihn heranlockte: Da auch er sich von

hlte & am letztern besonders nie vorbeigehen konnte,

Anmut & Talent angezogen fu

ohne es zu fordern &, mit der hochsten Ausbildung, es der besten auern Stellung

hren. [17] (Er machte dabei allerdings kaum einen Unterschied des

zuzufu

hlte sich von mannlicher Begabung so hingerien als von

Geschlechtes, & fu

weiblicher.) Vierer Sangerinnen erinnere ich mich, deren er in Budapest Erwahnung

nstigem

tat: Der Bianchi, Artner, Hilgermann & Cillagi; welch Letzterer, er nach ungu

hnengeschick, durch richtige Verwendung, zu Glu

ck & Ruhm verhalf. Weitauf

Bu

die Erste an Begabtheit & Konnen war Bianca Bianchi, die Primadonna; der

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 19 of 54

I fear that these doubtless most gripping documents of a noteworthy and most loving womans

soul no longer exist. (Hopefully Fr. Weber has faithfully kept Mahlers letters!) But I know that

Justi, who among all those close to Mahler had the greatest influence on himwhich she by no

means always used for the bestwas jealous of all women, not only those who meant something to

Gustav, but also of every trace of them (letters and recollections). She once managed to get his

permission to make an auto-da-fe of his letters. [15] This would probably have included those

from Marion! And, to state it already here: innumerable letters of mine to Gustav (except for the

few I keep myself ) went up in flames that day. For my part, I own almost no missives from Mahler,

since on this point I gave in to him, who was as fond of receiving letters just as much as he disliked

writing them, all the more since we, after all, had the most frequent and intense interaction for 10

years. On the other hand, he opened himself up to verbal communication about absolutely

everything in a way that I have experienced with no one I have ever met, either before or after.

And that was one of the most lovable aspects of his needy and devoted nature.

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

contents!* [15] But even this, the greatest of Mahlers loves, ultimately exhausted

itself in the hopelessness of the situation.

When we, his Vienna friends, saw Gustav here in passing shortly after he had

left Leipzig and Lake Starhemberg, we were shocked by his poor appearance and restless, deeply depressed state of mind, which expressed itself, among other ways, in the

opinion that he would never again find a job. Some two years later, after he had

become director of the Budapest Opera and I visited him there (do you remember

from my Mahler recollections?),27 he had recovered his equilibrium. Still, I found

that, despite being happy about my coming, he was burdened by difficult memories as

well as sadness amid his loneliness. In addition, despite his great communicativeness

with me, he did not mention [16] a single word about what lay too heavily on his

heart. Only later, in Berchtesgaden, did he pour forth his soul to me regarding this in

many, many tales. But what served as the strongest evidence of his profound devastation in the wake of this Leipzig episode of love and anguish was that he had not composed anything major since that time, a period of ten years.28

In Budapest it was well-nigh impossible for him to avoid personal attentions and

attractions with the personnel at the Opera. And, as always, it was primarily the

women that were drawn to Mahlers position [Stellung], but also in particular to his

genius, which they tended to recognize and greatly admire more readily [than did the

men]. Since he, too, was attracted by charm and talent, he especially could never

pass over the latter without stimulating it and bringing it to its highest level by means

of the finest instruction. [17] (Here he made hardly any distinction with regard to

gender and was as enthusiastic about male talents as female.) I remember four singers

he mentioned in particular in Budapest: Bianchi, Artner, Hilgermann, and Cillagi,29

the last of whom he helped to fortune and fame by correcting her ungainly stagecraft.

By far the foremost as regards talent and ability was Bianca Bianchi, the prima donna,

Page 20 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

rlich auch best gelegen war, mit dem Direktor gut Freund zu sein. Sie stu

rzte

es natu

rdigkeit & Gefalligkeiten auf ihn; half ihm seine

sich denn auch mit Liebenswu

Pesterwohnung einzurichten & Dgln. [ Dergleichen] & er hinwiderum [sic] musizierte viel & gern mit ihr. Wobei es wahrscheinlich nicht stehengeblieben ware,

hatte sie bei Gustav starkern Widerhall gefunden (als mir wenigstens von dieser

Sache zu Ohren kam.)

lerin, Jenny

In Pest war es auch, wo er viel in das Haus seiner ehemaligen Schu

Feld kam, einem ernsten, [18] nicht schonen, aber gebildeten & bes. [besonders]

hochmusikalischen Madchen, welches Mahler, seit den jugendlichsten

Wienerstunden, bewunderte & liebte, & dessen Eltern eine Verbindung mit dem, zu

hoher Stellung gelangten, einstigen armen Konservatoristen, gerne gesehen hatten.

Denn als sie spater einen Bankdirektor Perin heiratete, sagte der Vater zu Justi, die mit

Gustav bei der Trauung war: ,,Sehen Sie, an meiner Tochter Seite hatte jetztwar es

sein Wunsch gewesenIhr Bruder stehen konnen!Doch blieb die Freundschaft

el

zwischen Jenny & den Mahlerschen Geschwistern bestehen. Sie verfolgte von Bru

hrungen von Mahlers Werken & berichtete

aus, wo sie in ihrer Ehe lebte, die Auffu

ber. & als sie mit den Ihren [sic] spater auf einige Jahre nach Wien

ihm schriftlich daru

hte der personliche Verkehr wieder ebendig zwischen ihnen auf.

versetzt ward, blu

[19] Im Jahr 1891 verlie Mahler die Pester-Oper, wo man, statt seine unglaublichen

Leistungen ihm zu danken, die Befugnisse seiner Stellung ihm auf Tritt & Schritt

einschranken hatte wollen. (Bes. der unbedeutende, unfahige Intendant, Graf Geza

Zichyals einarmiger Pianist &schlechter Komponist seinerzeit bekanntda sie

Gustav zur wahren Holle ward.)

hlte er sich die erste Zeit sehr einsam &

In Hamburg, wohin er darauf kam, fu

cklich daru

ber, einen Flug nach Wien tun zu

benutzte jede Gelegenheit, & war glu

konnen. Da wir seit meinem Pesterbesuch herzlich befreundet waren, durfte ich

dabei nie fehlen & es waren wunderschone, angeregteste Abende, die wir da aus der

lebendigen Gelegenheit heraus, mit Gustavs herrlicher Musik oder den beschwingtesten Gesprachen, verbrachten. Bei einer solchen Zusam-[20]menkunft wo

Mahler, der Sympathien, wie Antipathien nie maigen, oder verbergen konnte (da

ich ihm spater oft sagte, wenn er Einem gut sei, verderbe er sichs mit allen

Anderen)als er dieses Abends mich so gar auszeichnete, in mirden altern anwesenden Freunde wegenfast peinlicher Weise, nahm er, bei Gelegenheit von

r den nachsten Sommer einen

Ferienplanen, mir das Versprechen ab, mit Justi fu

r die ganzen Ferien zu

Gebirgs-Aufenthalt auszufinden & sie daselbst, womoglich fu

besuchen. Ich aber war jener Zeit stets die Sommer mit meiner liebsten Freundin,

Josefine Spiegler, nach Tirol gezogen & verlebte diesenwahrend Mahlers in

Berchtesgaden warenin Seis mit ihr. Da kam eines Tags ein enttauscht-unzufriedener

nstigen Kollegin sei, die ihr Besuchsverheien

Brief von Gustav: Was es mit der ,,migu

lle? Mein Vorhaben jedoch war, Mahler erst im Herbst in

[21] so lang nicht erfu

Hamburg aufzusuchen, wo ich seiner & seiner gottlichen Musik ungestort mich erfreuen

konnte, statt in dem von allzuvielen Gasten & Bekannten heimgesuchten, unruhigen

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 21 of 54

[19] In 1891 Mahler left the Budapest Opera, where, instead of thanking him for his

unbelievable accomplishments, they wanted to limit the powers of his office at every

turn. (Especially the insignificant, incompetent intendant Count Geza Zichy,32 recognized in his day as a one-armed pianist and bad composer, who made life hell for

Gustav.)

In Hamburg, where he went next,33 he at first felt very lonely. He was happy

to take every opportunity to make a trip to Vienna. Since we had become close

friends ever since my visit to Budapest, I had to be present without fail, and those

were wonderful, most stimulating evenings that gave us the opportunity to spend

time with Gustavs magnificent music or in the most engaging conversations. At

one of these gatherings, [20] at which Mahler, who could never temper or hide his

sympathy or antipathy (such that I later often told him that when he likes one

person, he ruins it for himself with all the others)this particular evening he

praised me in such a way that it was, on account of his older friends also present

almost embarrassing; he made me promise, when the subject of vacation plans was

raised, to go with Justi to find a place for a holiday in the mountains that coming

summer and to stay there with them if possible for the whole vacation. But in those

days I always went to Tyrol for the summer with my dearest friend, Josefine

Spiegler,34 and spent it with her in Seis while the Mahlers were in Berchtesgaden.35

Then one day a disappointed and discontented letter came from Gustav: whats

with the begrudging colleague who has not yet fulfilled her promise to visit? [21]

My plan, however, was not to call on Mahler until the fall in Hamburg, where I

could enjoy him and his heavenly music without disturbance, in contrast to unruly

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

who, of course, was best situated to become good friends with the director. She threw

herself at him with charms and favors, helped him decorate his Budapest apartment,

and the like. And he, in turn, often and very happily played music with her, although

that would probably not have remained the extent of it had she found greater reciprocation from Gustav (at least as far as I heard about the matter).

It was also in Budapest that he often visited the home of his former pupil, Jenny

Feld,30 an earnest, [18] not pretty, but refined and exceptionally musical girl, who

had admired and loved Mahler since her first youthful lessons in Vienna, and whose

parents would have been happy to see a betrothal with the formerly poor conservatory student who had made it to such a high position. When she later married the

bank director Perin, her father said to Justi, who attended the wedding along with

Mahler: Look, had it been his wish, your brother would now be standing at the side

of my daughter!31 Still, the friendship between Jenny and the Mahler siblings

endured. From Brussels, where her marriage had taken her, she kept up with performances of Mahlers works and sent him written reports about them. And later on,

when she and her family were transferred to Vienna for a number of years, the lively

personal interaction between them blossomed anew.

Page 22 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

,,Zu der Liebesnachte Kuhlung,

Wo die stille Kerze leuchtet,

Da ergriff uns hohre Fuhlung . . .

Ohne Erklarung, Frage & Schwur verschmolzen unsre Psyche & Physis ineinander.

Und wenn sich endlich Eins den Armen des Andern entwand &, ,,umrungen von

chtige Kochin Elise schlief nachbarlich in der

Gefahrdenn die neugierig-klatschsu

Hohe, & unten mute ich an Justis Zimmer vorbei in mein Kammerlein schleicklich zur Ruh gelangt, schlief man einen kurzen, doch kostlichen

chenaber glu

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Berchtesgaden. Wahrend ich Gustav meinen Plan schrieb, war die entsetzliche

Cholera in Hamburg ausgebrochen. Mahler, schon auf dem Wege dahin, hatte in

Berlin die Kunde davon, zugleich mit der verlangerten Schlieung der Theater erfahckgekehrt. Davon unterrichtet, machte ich mich

ren, & war nach Berchtesgaden zuru

r den Freund, eilends dahin auf, wo ich wenige Stunden nach

nun, voll Sorgen fu

seiner erneuten Ankunft eintraf. (Du erinnerst Dich, liebster Hans, dieser

Begebenheiten wol aus meinen ,,Erinnerungen an G.M., die ich hier, weil sie mir

pfen des Folgenden notig

momentan nicht vorliegen, [22] & weil sie zum Dranknu

sind, wiederholte. )

Die Freude, den diesmal der Gefahr Entrannenen wiederzusehen & zugleich

ber seinem Haupte schwebten,

die Furcht vor den Gefahren der Zukunft, welche u

vereinigten sich zum gesteigertsten Empfinden & Genieen der Gegenwart; und

auch urplotzlich, machtig, unwiderstehlich hielt die Liebe Einzug in unsren Herzen.

Wenn die Freuden des Tages mit wonnigen Spaziergangen, frohlichen Mahlern,

r Gustav & mich unsre Zeit erst an.

Musicieren & Lesen verklungen waren, brach fu

chtige Schwesterlein ausgeNachdem wirwas nicht leicht warJusti, das eifersu

dauert, zog mich Gustav in sein oberstes Dachgela, ein schragwandiges, winziges

Kammerlein, mit der weitumfaendsten, Herzerhebendsten Aussicht auf den wundervollen Berchtesgadenerkeel, bis zu den hochsten Eisgebirgen [23] der Ferne.

Wie wir da, eingeschlossen, & von aller Welt abges[c]hlossen, im engsten Raum, bis

zum grauenden Morgen im innig-bewegtesten, Scheherazaden-artigen Erzahlen,

unser ganzes Leben vor einander entrollten; wie in Mahler, durch meinen Glauben

an seinen Genius, & begeiste[r]ter Ansporn, die 10 Jahre lang versiegte

Schaffenskraft, machtiger als je zuvor, aufs Neue entsprangum nach unglaublich

vollbrachter Riesenarbeit seiner 10 ungeheuren Symphonien & wundervollen Lieder

erst mit dem Tode zu enden; da wo sich in uns Alles suchte, &in seltener

Wahlverwandtschaftseelisch & geistig, wechselseitig gebend, wie empfangend,

sich fand;wo aus der Gelegenheit der Gelegenheiten heraus, der Himmel selbst

hrt zu haben schien: Wars da nicht Wunderja Su

nde

uns zusammengefu

gewesen, wenn solcher Lebens-Verklarung & Vollendung nicht [24] auch der

llte sichs:

hochste Liebesausdruck nachgefolgt ware? Und so erfu

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 23 of 54

In the coolness of the night of love,

Where the silent candle glows,

There higher feeling seized us . . .39

Without any declaration, question, or pledge, our psyche and physis melted into

each other. 40 And when at last the arms of one were wrested from the other and,

surrounded by danger [umrungen von Gefahr]41for the curious, gossipy cook,

Elise, slept nearby on high, and below I had to sneak by Justis room to get to my

chamberyet happily getting to rest, one slept a short but delightful sleep in order to

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Berchtesgaden, where all-too-many guests and friends had alighted. While I was

writing to Gustav of my plan, the horrible cholera epidemic broke out in Hamburg.36

Mahler, already on the way there, found out about it in Berlin, along with the

extended closing of the theaters, and traveled back to Berchtesgaden. Informed

about this and full of worry for my friend, I headed there as quickly as possible, where

I arrived a few hours after his return. (You no doubt remember this event, dearest

Hans, from my Recollections of G.M.,37 which I have repeated here because I do

not have it in front of me at the moment, and [22] because what happened is necessary for the connection to what follows.)

The joy at again seeing the one who had this time escaped imminent danger

and the simultaneous fear of future dangers hanging over his head came together in

the most intense awareness and enjoyment of the present, and then quite suddenly,

powerfully, irresistibly, love entered our hearts. When the joys of the day with blissful walks, festive meals, music making, and reading had faded away, the time for

Gustav and me was just beginning. After we had outlasted Justi, the jealous little

sisterwhich was not easyGustav drew me up to his room in the attic, a tiny

chamber with a slanting wall and with the most panoramic, heart-inspiring view of

the Berchtesgaden basin up to the highest glacial mountains [23] in the distance.

The way we found ourselves there, locked in in tight quarters and separated from the

rest of the world, unfolding our entire lives for each other until the early dawn in the

most intimate, moving, Scheherazadian manner of telling; the way that the creative

power in Mahler, drained away for ten years, returned anew, more powerful than ever

because of my belief in his genius and my enthusiastic encouragementand would

only end with his death after the unbelievable completion of a tremendous oeuvre

comprising ten formidable symphonies and wonderful songs; there, where everything searched for andin uncommon elective affinity38found itself in us, alternately giving and taking of itself in spirit and mind, where in the moment of

moments it seemed as if the heavens themselves had brought us together, would it

not have been a wonder, even a sin, if such a transfiguration and consummation of

life had not [24] been followed by the highest expression of love? And so it came to

be:

Page 24 of 54 The Musical Quarterly

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

Schlaf, um nach wenigen Stunden erfrischt beschwingtest aufzuwachen: Denn gibt

ck auf Erden, als in den Tag zuru

ckzukehren mit dem Bewusstsein

es ein hoheres Glu

zu lieben & geliebt zu werden?! Und dann, all die holden Erkennungszeichen, welche

nur [25] den Liebenden bewut, sie, in einem ,,verborgenen Gespinnst von

Minnen, unsichtbar am hellen Tage, beseeligt unter den Andern wandeln lasst.

Und jedes lebendige Wort & frohe Tun wird nun zum Fest;von dem man doch

ckkehrtwo jedes Abends letzter Ku:

umso verlangender zum Zweisamsein zuru

,,Ein treu verbindlich Siegel: So wird es auch am nachsten Tage bleiben!

rchtete Abschied herantausendfach

Doch schneller als geahnt kam der gefu

rchteter, weil Mahler sich in die noch keineswegs beendete Gefahr der

gefu

gralichen Hamburger-Seuche begeben sollte, & kraftvoll-tapfer sein Wort, auch

nchen[,]

unter diesen aufhebenden Umstanden halten wollte: Er verabredete in Mu

ber die Versorgung seiner

wohin Justi & ich ihn geleitet[,] noch Alles mit mir, u

Geschwister, falls ihm etwas zustiee;eine letzteste Liebesnacht mit mir in

Seligkeit & Thranen& er war uns entrien!

[26] Gustav hatte mir das Versprechen abgenommen, ihn sobald als moglich in

Hamburg zu besuchen. Es ist in jenem Winter nicht geschehen. Denn bald bemerkte

ich aus seinen wenigen Anworten (auf die Hochflut meiner Briefe) in denen das

ndliche Liebeswort einem kameradschaftlichen Schreibton gewichen war, da er

mu

r mich bekampft & besiegt hatte; worauf

sein leidenschaftliches Empfinden fu

ichnie gewohnt & gewillt eines Menschen Liebe zu erzwingensogleich ohne

Groll & Vorwurf einging. Spater erst wurde mir bewut, da hinter jener Wandlung

ndlich Alles aufbot, jede warmere

vor Allem Justi stand, die brieflich & mu

Beziehungin diesem Fall war es die meinedie ihr Verhaltnis zu Gustav zu

gefahrden schien, im Keime zu ersticken. Sie fuhr im Laufe des Winters nach

ngern Schwester, & dem

Hamburg, wohin sie spater [27] vollig mit Emma, der ju

bersiedelte.

ganzen Haushalt, zu Gustav u

Um Mahlers Leben zu verstehen mu man wien, da vom Tode der Eltern bis

ck & -Unglu

ck seines

zu seiner Ehe, diese Lieblingsschwester Justi das Hauptglu

ck, weil sie ihn leidenschaftlich, wie keinen

Daseins ausmachte. Ich nenn es Glu

r ihn sorgte. Unglu

ck aber

zweiten Menschen auf Erden liebte, & treu & trefflich fu

war ihre grenzenlose Eifersucht auf ihn, die sie nicht etwa offen zeigte, denn sie

wute, da sie sichs dadurch mit ihm verdorben hatte, wol aber versteckt walten

lie. Da war ihr kein Weg zu schlecht, kein Betrug zu gro zur Erreichung ihres Ziels.

Da es ihren Machinationen aber stets gelang, dazu kam ihr nicht nur Gustavs Liebe

r sie zu Statten, sondern, bei Diesem auch eine Art von Askese,

& groe Schwache fu

rftesein Geist als

welche tief in ihm wurzelte, & diewenn ichs so nennen [28] du

h errungen hatte; umsomehr vielGegenwehr einer starken Sinnlichkeit, sich fru

leicht, weil eine groe Wechselhaftigkeit & Unzuverlaigkeit bei seinen Neigungen

zu Menschen in ihm lag, die er zwar nicht Wort haben wollte, aber hin & hergerien

davon, doch fortwahrend an sich erfahren mute.Was aber Justi betrifft, tate man

Unrecht zu glauben, da sie nicht auch ihre guten & lieblichen Seiten hatte. Ja,

Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women Page 25 of 54

Downloaded from http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on July 7, 2014

wake up a few hours later refreshed and inspired. For is there a higher happiness on

earth than to return to the day amid the consciousness of loving and being loved?!

And then all the precious signs of recognition only [25] known to the lovers that

allow them to walk, euphoric, invisible in broad daylight among the others in a

hidden gossamer of courtly love.42 And every living word and happy act becomes a

festival from which one all the more desirously returns to togetherness, where every

evenings last kiss is a seal of fidelity: thus it will remain the next day!43

But the dreaded departure came faster than suspected, a thousand times more

dreaded because Mahler was to head into the danger that was far from over in the

horrible Hamburg epidemic, keeping his word in a resolute and courageous manner

even under such exceptional circumstances. In Munich, whence Justi and I accompanied him, he arranged everything with me concerning the care of his siblings should

anything happen to him. A very last night of love with me, in bliss and tearsand

then he was torn from us!44

[26] Gustav made me promise to come and visit him in Hamburg as soon as

possible. That did not happen that winter. For I soon noticed in his sparse answers

(in response to the flood of letters from me) that the spoken words of love had given

way to a comradely tone of writing, that he had fought and conquered his passionate

feelings for me. Whereupon I, who have never wanted or been inclined to force

someones love, went along with this immediately, without resentment or accusation.

Only later did I realize that it was above all Justi who was behind this transformation,

and who, in letters and conversation, did everything in her power to nip in the bud

any warmer relationshipin this case minethat appeared to threaten her relationship to Gustav.45 During the course of the winter she traveled to Hamburg, where

she later [27] moved in completely with Gustav, along with Emma,46 the younger

sister, and the entire household.

In order to understand Mahlers life, it is necessary to know that, from the

death of his parents up until his marriage,47 this favorite sister of his constituted the

most important source of happiness and also of misfortune in his existence. I call it

happiness because she loved him passionately, like no other person on earth, and

took care of him with devotion and skill. But the misfortune was her boundless jealousy toward him, which she did not simply reveal openly, for she knew that in doing

so she would have ruined things with him, but rather let it reign in secret. No

method was beneath her, no deception too great for the attainment of her goal. That